Abstract

Purpose

Our aim was to assess operative treatment for post-traumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH) in adolescents.

Methods

Eleven patients with an average age of 17 (range 14–26) years were operated up on for ANFH after proximal femoral fractures. The average interval between injury and reconstructive surgery was four (range two to eight) years. The average follow-up of the entire cohort was 89 (range 48–132) months. Five patients with total ANFH were treated by total hip replacement (THR). Six patients with partial ANFH were treated with valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO).

Results

In all patients, operation improved hip function. The average preoperative Harris Hip Score (HHS) was 70 points and average postoperative HHS was 97 points. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans before and after VITO demonstrated resorption of the necrotic segment of the femoral head and its remodelling in all six patients with partial ANFH. A complication was encountered in one patient.

Conclusion

Patients treated for ANFH had good medium-term outcomes after THR for total necrosis and also after VITO for partial necrosis.

Introduction

Proximal femoral fractures in adolescents are rare but very serious injuries [1–8]. Their most severe and most frequent complication is avascular necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH) [8–12], described for the first time by Axhausen in 1924 [13]. Varus malunion or nonunion is less frequent. The incidence of these complications has been reported by many authors, but few of them deal in detail with the possibility of their operative treatment [14–20]. The largest series of 11 patients treated by valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO) was published by Boitzy [15] in 1970 with the follow-up of three years. There is no consensus in the literature on the treatment of complications, ANFH in particular [4, 7–10]. Therefore, we decided to present our own experience with a four to 11-year follow-up after reconstructive surgery for ANFH.

Patients and methods

Patients

Between 1999 and 2006, we operated on 11 patients (two male and nine female patients) for ANFH after fracture of the proximal femur. Their average age at the time of injury was 13 (range nine to 19) years and at the time of reconstructive surgery 17 (range 14–26) years, with the average interval between injury and reconstructive surgery of four (range one to seven) years. Four patients sustained polytrauma in car accidents, including, in three cases, transphyseal separation of the femoral head and in one case transcervical fracture of the femoral neck. Fall from a tree or during downhill skiing resulted in a displaced transcervical fracture of the femoral neck in five cases and a peritrochanteric fracture in one. In one male patient, a transcervical fissure of the femoral neck occured after he slipped on the floor. With regard to primary treatment, five patients were treated in our department and six in another hospital. Three patients were treated nonoperatively: two for a nondisplaced transcervical fracture of the femoral neck (patients 7 and 8,) and one for a displaced transcervical fracture of the femoral neck (patient 1). The remaining eight patients underwent operation. Transphyseal separation was fixed with Kirschner (K) wires in three patients. Displaced transcervical fractures were treated in one case with a dynamic hip screw (DHS) and in three cases with lag screws. The peritrochanteric fracture was also fixed with lag screws.

In all patients, an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and the frog-leg views and AP radiograph of the affected hip were assessed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were taken in the frontal and sagittal planes. Transphyseal separation of capital epiphysis and its displacement from the acetabulum resulted in all three cases in total ANFH (patients 3, 4, 5). Nondisplaced transcervical fissure or fracture of the femoral neck resulted in two cases in partial ANFH (patients 7, 8). Displaced transcervical fracture of the femoral neck resulted in two cases in total ANFH (patients 1, 2) and in three cases in partial ANFH (patients 6, 9, 11). Peritrochanteric fracture resulted in partial ANFH (patient 10).

Patients were divided into two groups according to necrosis type. The first group comprised five patients with total ANFH, i.e. type I Ratliff classification, and the second comprised six patients with partial ANFH, i.e. type II Ratliff classification [12] (Table 1). Corresponding to this division into two groups were patient complaints. Patients with total ANFH complained of severe pain and significantly limited range of motion. Patients with partial ANFH complained of pain, although not so severe as in the first group, but associated in four cases with a limp caused by a 2-cm limb shortening.

Table 1.

Patient overview

| Patient no. | Gender | Year of injury | Type of fracture | Primary Treatment | Age at injury (years) | Age at reconstructive surgery (years) | Interval injury-reconstructive surgeryy (years) | Year of reconstructive surgery | Type of complication | LLD (cm) | Type of reconstructive surgery | Notice | Follow-up (months) | HHS before surgery | HHS after surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 1993 | TCD | Nonoperative | 13 | 20 | 7 | 2000 | Total ANFH | 2 | THR | 120 | 63 | 99 | |

| 2 | F | 1991 | TCD | Lag screws | 18 | 26 | 8 | 1999 | Total ANFH | 1 | THR | 132 | 65 | 98 | |

| 3 | F | 1999 | TPS | K wires | 13 | 16 | 3 | 2002 | Total ANFH | 7 | THR | 84 | 33 | 98 | |

| 4 | F | 2001 | TPS | K wires | 13 | 15 | 2 | 2003 | Total ANFH | 2 | THR | 96 | 61 | 98 | |

| 5 | F | 1999 | TPS | K wires | 12 | 18 | 6 | 2005 | Total ANFH | 1 | THR | Bilateral fracture right PT, left TPS | 60 | 63 | 99 |

| 6 | F | 1997 | TCD | Dynamic hip screw | 12 | 17 | 5 | 2002 | Partial ANFH | 1 | VITO | 96 | 90 | 93 | |

| 7 | M | 1996 | TCnD | Nonoperative | 13 | 16 | 3 | 1999 | Partial ANFH | 2 | VITO BHSA | 132 | 73 | 93 | |

| 8 | M | 2003 | TCF | Nonoperative | 12 | 14 | 2 | 2005 | Partial ANFH | 2 | VITO | Final leg shortening 1 cm | 60 | 90 | 100 |

| 9 | F | 1999 | TCD | Lag screws | 9 | 14 | 5 | 2004 | Partial ANFH | 2 | VITO BHSA | Final leg shortening 1 cm | 72 | 90 | 100 |

| 10 | F | 1996 | PT | Lag screws | 12 | 18 | 6 | 2002 | Partial ANFH | 2 | VITO | Osteotomy nonunion | 78 | 79 | 96 |

| 11 | F | 2004 | TCD | Lag screws | 19 | 21 | 2 | 2006 | Partial ANFH | 1 | VITO | 48 | 58 | 93 |

HHS Harris Hip Score, LLD leg length discrepancy before surgery, TCD transcervical displaced fracture, TCnD transcervical nondisplaced fracture, TPS transphyseal separation, PT pertrochanteric fracture, ANFH avascular necrosis of femoral head, THR total hip replacement, VITO valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy, SITO shortening intertrochanteric osteotomy, BSHA Bosworth hip-shelf arthroplasty

In all five patients with total ANFH, the femoral head showed marked destruction. In all six patients with partial ANFH, necrosis was clearly visible on the radiograph. The polar segment of the femoral head was affected in five cases and its superolateral segment in one case. Sphericity of the femoral head in patients with partial ANFH was markedly distorted in two cases only. One was a case of mushroom deformity (patient 9), and in the other, the lateral half of the femoral head was distorted with a saddle-shaped deformity (patient 10). In two cases, partial ANFH was associated with shortening of the femoral neck by 1 cm and in four cases by 2 cm.

In all but one patient (patient 8), the capital and trochanteric physes of the injured femur were closed at the time of reconstructive surgery. In patient 8, the physis of the greater trochanter and medial part of the capital femoral physis were still open. In all patients except two (patients 8, 9), the physes of the contralateral noninjured proximal femur were closed at the time of reconstructive surgery. THR was performed in five patients with total ANFH. The remaining six patients with partial ANFH were deemed suitable for VITO based on radiographic examination and MRI. The aim of the osteotomy was to move the necrotic segment from the weight-bearing zone of the acetabulum and correct the leg shortening. Two cases with partial ANFH required additional operations. The Bosworth hip-shelf arthroplasty was required to compensate for insufficient coverage of the femoral head (patients 7, 9). The indication in both cases was a centre-edge (Wiberg) angle <10°.

Operative techniques

All patients except for patient 7 were operated up on by the first author.

THR

In all the five patients, cementless THR was performed in a standard manner with the patient in the supine position from the anterolateral Watson–Jones approach. In all cases, we used a conical screw cap (Zweymüler type), polyethylene (PE) insert, aluminium ceramic head of 28 mm and a cementless stem (Spotorno type).

VITO

This technique was performed in the same manner as described in detail for adults [21, 22]. Preoperative planning based on radiographic examination was crucial to the success of the surgery. AP radiographic view of the pelvis and AP radiographs of the affected hip in 15° internal rotation were obtained in each case. An AP view was traced on paper as the first step of the preoperative surgical plan. The osteotomy was planned at the level of the top of the lesser trochanter. Subsequently, the osteotomy line was drawn parallel to the plate blade. In the next step, the wedge to be resected was drawn on the distal fragment. Then, the two illustrated fragments were cut out, matched, and the impact of the lateral displacement of the distal fragment on the limb lengthening was determined.

At surgery, the patient was placed in a supine position, and a lateral longitudinal approach was used. After stripping the proximal portion of the vastus lateralis muscle, an L-shaped anterior arthrotomy running in the direction of the lesser trochanter was done. This improved visualisation for the introduction of the plate blade and made it possible to release the insertion of the medial part of the capsule in the area of the lesser trochanter, including the iliopsoas tendon. The seating chisel was inserted, using the anterior surface of the femoral neck served as a landmark.

The osteotomy line was made parallel to the inserted chisel. The wedge angle was determined on the basis of preoperative measurement and ranged between 30 and 40°. After the removal of the seating chisel, the plate blade was inserted in the proximal fragment. If a lateral displacement of the femoral shaft was planned, a blade 1–1.5 cm longer than originally determined by the depth of the seating chisel was chosen. As a result, the length of the lateral part of the blade corresponded to the planned lateral displacement of the protruding part of the proximal femur. Subsequently, a careful valgus reduction of fragments was done with the limb in abduction. The plate was then fixed to the femoral shaft, limb length and range of motion in the hip joint were examined, drains inserted, and the wound closed. Postoperative AP and lateral radiographs were obtained. The patient’s hip was immobilised; crutches were permitted, for nonweight bearing on the affected extremity. Full weight bearing was usually allowed after three months. Hardware was removed within one year after osteotomy.

Additional procedures

Bosworth shelf arthroplasty was performed following the original descriptions [23]. Patients were operated up on in the supine position through the Smith–Petersen approach. Close above the attachment of the superior articular capsule of the hip joint, an arch-shaped notch 3-cm wide and 5-cm long, was made with a chisel just above the acetabulum, passing obliquely proximo-medially as far as the inner cortex of the iliac bone. A 2 × 5 × 5 × 4-cm monocortical bone graft harvested from the iliac wing was firmly hammered into the notch. This self-locking extra-articular graft covered the superior aspect of the femoral head sufficiently without limiting the range of movement in the hip joint. Postoperative management was the same as for intertrochanteric osteotomy.

Postoperative assessment

Subjective evaluation was based on patients’ satisfaction with the surgery. Objective assessment included VITO healing time, limb lengthening and potential complications. Harris Hip Score (HHS) [24] was assessed in all patients. In patients with partial ANFH, MRI examination was performed two to three years after the osteotomy based on which resorption of the necrotic segment was evaluated. In addition, the relationship between fracture type of the proximal femur and subsequent complications was analysed.

Results

The average follow-up period for the entire series was 89 (range 48–132) months. In the first group of patients, those with total ANFH treated by THR, the average follow-up was 98 (range 60–120) months. In the second group, those with partial ANFH treated with VITO, follow-up averaged 81(range 48–132) months. A brief overview of the results is presented in Table 1.

Patients treated with THR

All patients healed without complications, and in all of them, shortening of the affected limb was compensated for and range of movement was only minimally limited compared with the contralateral side. All patients were highly satisfied with the result six to ten years after the surgery (Table 1). In the meantime, two patients had a baby. No signs of implant loosening were noted at the final follow-up.

Healing and complications of VITO

The surgical site healed without complications in all patients. Intertrochanteric osteotomy healed in all patients within three months, except for female patient 10 in whom nonunion occurred requiring treatment five months after osteotomy. Refixation with a 95°-angled blade plate and lag screw resulted in firm bone union after four months (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). No complications were encountered after the additional procedure, i.e. after Bosworth hip-shelf arthroplasty (Figs. 4 and 5). Hardware was removed within one year of osteotomy.

Fig. 1.

Patient 10. a An 18-year-old woman with partial avascular necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH) of the right hip after pertrochanteric fracture of the femoral neck 7 years after injury. b Postoperative radiograph after valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO). c Nonunion of osteotomy 5 months after surgery. d Refixation with 95°-angled blade plate. e Healing of nonunion 4 months after refixation. f Right hip 30 months after VITO and 26 months after refixation

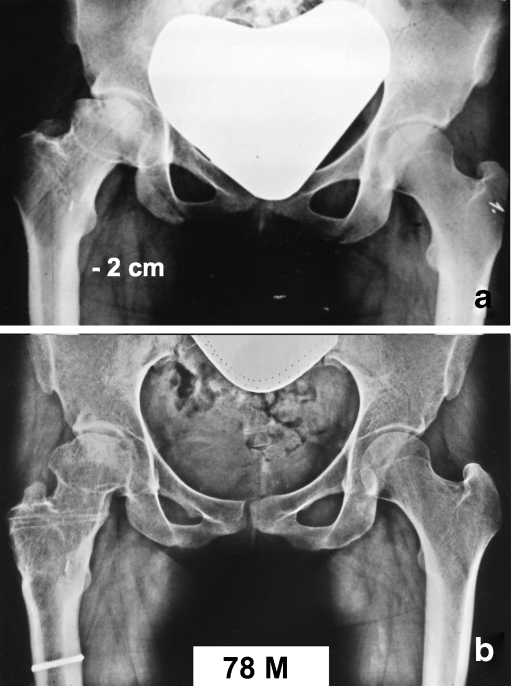

Fig. 2.

Patient 10. a Pelvic radiograph before reconstructive surgery, shortening of the right limb of 2 cm. b Pelvic radiograph 78 months after valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO) showing no leg-length discrepancy

Fig. 3.

Patient 10. a Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO). b MRI 26 months after VITO

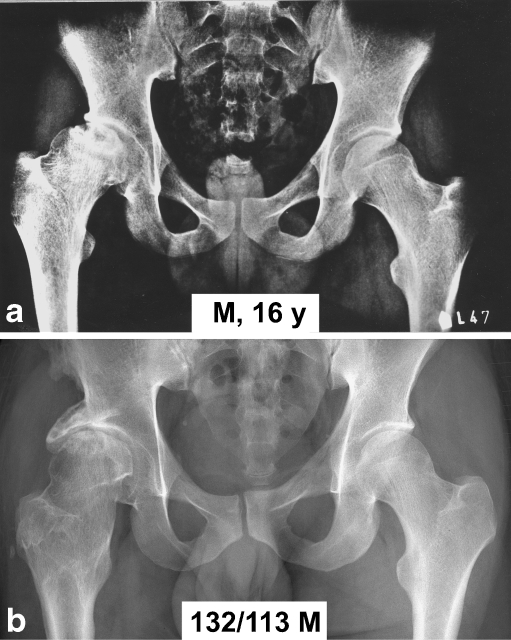

Fig. 4.

Patient 7. a A 13-year-old boy with transcervical fissure, conservative treatment without joint aspiration. b Partial avascular necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH) 3 years later. c Postoperative radiograph after valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO). d Nineteen months after VITO, the lateral half of femoral head is not covered by the acetabulum. e Postoperative radiograph after Bosworth hip-shelf arthroplasty. f Radiograph of the right hip 132 months after VITO and 113 months after Bosworth hip-shelf arthroplasty

Fig. 5.

Patient 7. a Pelvic radiograph before reconstructive surgery, shortening of the right limb of 2 cm b Pelvic radiograph 132 months after valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO) and 113 months after Bosworth hip-shelf arthroplasty; no limb-length discrepancy

Leg shortening

Primary leg shortening in patients with total or partial ANFH ranged between 1 and 2 cm. The only exception was female patient 3 in whom subluxation of the necrotic femoral head occurred with fibrous ankylosis in 20° adduction, pelvic obliquity and functional shortening of 7 cm. Leg shortening was fully corrected in all five patients treated with THR and in four patients treated with VITO. Maximum correction after VITO was 2 cm. In two patients (patients 8, 9) operated on at the age of 14 years with open capital physis of the contralateral femur, leg-length discrepancy was fully corrected by VITO. Subsequent growth of the unaffected contralateral femur resulted again in leg shortening of 1 cm.

Resorption of necrotic segment in partial ANFH

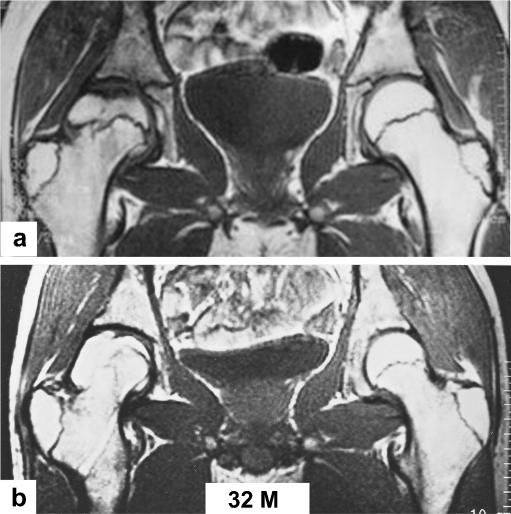

Comparison of MRI scans before and after VITO showed resorption of the necrotic segment of the femoral head and its remodelling in all six patients (Figs. 3 and 6).

Fig. 6.

Patient 8. a A 14-year-old boy with partial avascular necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH) of the right hip after transcervical fracture of the femoral neck 2 years after injury; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before reconstructive surgery. b MRI 32 months after valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy (VITO)

HHS

HHS values before reconstructive surgery and at the final follow-up are shown in Table 1. Mean preoperative HHS was 70 points, and mean postoperative HHS 97.

Discussion

ANFH after femoral-neck fracture in adolescents is repeatedly reported in the literature [1–20], but few articles deal with its operative treatment. Some authors recommend a nonoperative procedure [5, 6, 10], whereas others advocate operations preserving the femoral head, i.e. osteotomy of the proximal femur, coverage procedure or “trap-door” operation [4, 15–19]. In cases in which the femoral head can no longer be preserved, THR, cup arthroplasty, resection arthroplasty or arthrodesis is recommended [4, 6, 7, 20]. However, there is no consensus as to the choice of the optimal surgical procedure [6]. The main problem in evaluating different operative methods is the number of patients operated up on and the period of their follow-up.

In this study, we attempted to analyse the effect of primary treatment on the development of ANFH. Nevertheless, we found it impossible. Only five patients were primarily treated in our departments, and two of them were operated on within six hours of the injury. The other three patients were referred for surgery from other departments. In six patients treated primarily in other departments, it was impossible to obtain basic information concerning this treatment.

Valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy for coxa vara after adolescent femoral neck fracture was suggested first by Whitman in 1902 [14]. Boitzy [15] used valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy in 11 patients after a proximal femoral fracture: twice in case of varus malunion, once in varus nonunion, in five cases of ANFH and in three cases of varus nonunion associated with ANFH. Average patient age at the time of injury was 14 (range 8–20) years and at the time of osteotomy 20 (range 9–33) years. The follow-up was only one to three years. In patients with ANFH, the result was fair or poor. In one case, it was necessary to perform arthrodesis of the hip after the osteotomy. Forlin et al. [16] reported complications in a group of 16 children after proximal femoral fractures. Average patient age at the time of injury was 12 (range 5–16) years and average follow-up seven (range two to 24) years. In all cases, premature physeal closure occured. Reconstructive surgery was performed in eight patients, of which seven were an osteotomy and one a varus osteotomy. Indication for osteotomy was ANFH in one and ANFH associated with nonunion of the femoral neck in seven. A good result was achieved only once, fair results twice and a poor result five times. The authors did not specify the follow-up period of these eight patients. Nötzli et al. [18] described partial ANFH in three patients 13, 14 and 17 years old. All patients underwent intertrochanteric extension osteotomy. The follow-up period was three, three and a half and seven years, respectively. In two cases, the condition improved; in the third case, the femoral head was distorted. Leg shortening after osteotomy was 2.0, 2.5 and 2.5 cm, respectively. Abbas et al. [19] described three patients 12, 14 and 15 years old after a transcervical fracture of the femoral neck who underwent rotational transtrochanteric osteotomy for polar necrosis of the femoral head. The follow-up period was two, two and two and a half years, respectively. Limb length was not specified. Good results were achieved in all three cases. Ko et al. [17] used a “trap-door” procedure in three patients 12, 15 and 15 years old, with a segmental collapse of the femoral head after femoral-neck fracture. Subchondral bone grafting was combined in two cases with containment osteotomy of the femur and acetabulum. Follow-up was two, three and four years, respectively. Leg length prior to and after the operation was not specified. Good results were achieved in two cases and in one the operation failed.

Reconstructive surgery choice depends on the ANFH type. In total ANFH, the femoral head cannot be preserved, and it is therefore necessary to choose between hip fusion and hip arthroplasty. Opinions on hip fusion in adolescents vary [25, 26]. Its disadvantage is loss of hip movement, limb shortening and overloading of the lumbar spine, contralateral hip and ipsilateral knee. For these reasons and because all patients were young girls , they preferred THR after being informed about the pros and cons of the two options. In patients between 15 and 18 years of age, THR is indicated only exceptionally. Although THR is recommended in the literature for treating post-traumatic total ANFH, we found no description of a specific case in adolescents. Our results achieved so far are encouraging, but further follow-up is necessary.

In the partial ANFH, it was necessary to treat the necrotic segment of the femoral head and at the same time the leg shortening, including the relative overgrowth of the greater trochanter in relation to the femoral head, which is unfavourable for the function of hip abductors. Valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy allowed us to move the necrotic segment from the weight-bearing zone of the acetabulum and at the same time to correct the leg shortening and improve articular–trochanteric distance (ATD). In contrast, varus osteotomy is always associated with limb shortening and ATD reduction. Extension intertrochanteric osteotomy or transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy allows neither leg-length correction nor improved ATD. The trap-door procedure combined with containment femoral/acetabulum osteotomy is, in our view, too extensive and is associated with a risk of damage to the blood supply to the femoral head. We performed a coverage procedure in two of our patients (patients 7 and 12) after osteotomy healing and partial resorption of the necrotic segment.

Unlike the experience of the authors cited above [15, 18], in all six patients, we achieved a subjective and objective improvement that was confirmed by MRI in all six patients with partial ANFH treated by intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy. Significant in this respect, preoperative MRI scans in the frontal and sagittal planes allowed precise identificatiion of size and location of the necrotic segment of the femoral head and preparation of an exact plan for the correction intertrochanteric osteotomy. We were also able to evaluate the capital femoral physis and neck of the injured and contralateral proximal femurs. Comparison of pre- and postoperative MRI scans provided an objective result of the operation in terms of resorption of the necrotic segment of the femoral head. Surprisingly, none of the cited authors [16–18], except for Abbas et al. [19], mentioned MRI. Abbas et al. [19] used it only in one patient for preoperative diagnosis.

In partial ANFH, the situation is problematic in terms of long-term results. Untreated partial ANFH may lead to premature osteoarthritis of the hip. VITO does not bring about full biological and biomechanical restoration of the femoral head, but it may considerably slow down development of premature osteoarthritis of the hip. A group of six patients treated for partial ANFH with VITO is not large, but on the other hand, the mean follow-up period was six (range four to 11) years. In a search of the literature, we did not find a larger group of patients with the same or longer follow-up and detailed description of results.

The number of indications for intertrochanteric osteotomies is decreasing [27–29]. Nevertheless, based on the given facts, we consider VITO to be an efficient method for treating partial post-traumatic ANFH in adolescents. However, a more objective evaluation of this surgical method requires further continuous follow-up of our patients with partial ANFH.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic Grant IGA MZ: NS 9980–3 Importance of intertrochanteric osteotomy and acetabular coverage procedures in adolescents and adults for preservation of long-term hip function.

References

- 1.Ingram JA, Bachynski B. Fractures of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35-A:867–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kay SP, Hall JE. Fracture of the femoral neck in children and its complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971;92:155–188. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller WE. Fractures of the hip in children from birth to adolescence. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;80:53–71. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197305000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canale ST, Bourland WL. Fracture of the neck and intertrochanteric region of the femur in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59-A:431–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrissy R. Hip fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;152:202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes LO, Beaty JH. Fractures of the head and neck of the femur in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76-A:283–292. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boardman MJ, Herman MJ, Buck B, Pizzutillo PD. Hip fractures in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:162–173. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pape H-C, Krettek C, Friedrich A, Pohlemann T, Simon R, Tscherne H. Long-term outcome in children with fractures of the proximal femur after high-energy trauma. J Trauma. 1999;46:58–64. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon ES, Mehlman CT. Risk factors for avascular necrosis after femoral neck fractures in children: 25 Cincinnati cases and meta-analysis of 360 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:323–329. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swiontkowski MF. Complications of hip fractures in children. Complicat Orthop. 1989;4:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morsy HA. Complications of fracture of the neck of the femur in children. A long-term follow-up study. Injury. 2001;32:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratliff AHC. Fractures of the neck of the femur in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44-B:528–542. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.44B3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Axhausen G. Epiphyseonekrose und Arthritis deformans. Arch Klin Chir. 1924;126:341–363. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitman R. A new method of treatment for fracture of the neck of the femur, together with remarks on coxa vara. Ann Surg. 1902;36:746–761. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190211000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boitzy A. La fracture du col du femur chez l´enfant et l´adolescent. Paris: Mason; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forlin E, Guille JT, Kumar SJ, Rhee KJ. Complications associated with fracture of the neck of the femur in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:503–509. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199207000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko J-Y, Meyers MH, Wenger DR. “Trapdoor” procedure for osteonecrosis with segmental collapse of the femoral head in teenagers. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:7–15. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nötzli HP, Chou LB, Ganz R. Open-reduction and intertrochanteric osteotomy for osteonecrosis and extrusion of the femoral head in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:16–20. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbas AA, Yoon TR, Lee JH, Hur CI. Posttraumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head in teenagers treated by a modified transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy: a report of three cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:63–69. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31815aba30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linhart W, Stampfel O, Ritter G. Posttraumatische Femurkopfnekrose nach Trochanterfraktur. Z Orthop. 1984;122:766–769. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartoníček J, Skála-Rosenbaum J, Douša P. Valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy for malunion and nonunion of trochanteric fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:606–612. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatzker J, editor. The intertrochanteric osteotomy. Berlin: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosworth DM, Fielding JW, Ishizuka T, Ege R. Hip-shelf operation in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1961;43-A:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51-A:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stover M, Beaulé PE, Matta JM, Mast JW. Hip arthrodesis: a procedure for the new millennium? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:126–133. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafroth MU, Blokzijl RJ, Haverkamp D, Maas M, Marti RK. The long-term fate of the hip arthrodesis: does it remaina valid procedure for selected cases in the 21st century? Int Orthop. 2010;34:805–810. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0860-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haverkamp D, Eijer H, Besselaar PP, Marti RK. Awareness and use of intertrochanteric osteotomies in current clinical practice. An international survey. Int Orthop. 2008;32:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zweifel J, Wolfgang Hönle W, Alexander Schuh A (2011) Long-term results of intertrochanteric varus osteotomy for dysplastic osteoarthritis of the hip. Int Orthop 35:9–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Said GZ, Farouk O, Said HGZ. Valgus intertrochanteric osteotomy with single-angled 130° plate fixation for fractures and non-unions of the femoral neck. Int Orthop. 2009;34:1291–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0885-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]