Abstract

X chromosome inactivation (XCI) is a striking example of developmentally regulated, wide-range heterochromatin formation that is initiated during early embryonic development. XCI is a mechanism of dosage compensation unique to placental mammals whereby one X chromosome in every diploid cell of the female organism is transcriptionally silenced to equalize X-linked gene levels to XY males. In the embryo, XCI is random with respect to whether the maternal or paternal X chromosome is inactivated and is established in epiblast cells upon implantation of the blastocyst. Conveniently, ex vivo differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) recapitulates random XCI and permits mechanistic dissection of this stepwise process that leads to stable epigenetic silencing. Here, we focus on recent studies in mouse models characterizing the molecular players of this female-specific process with an emphasis on those relevant to the pluripotent state. Further, we will summarize advances characterizing XCI states in human pluripotent cells, where surprising differences from the mouse process may have far-reaching implications for human pluripotent cell biology.

MESH keywords: X chromosome Inactivation; Nuclear reprogramming; Pluripotent Stem Cells; Heterochromatin; X (inactive)-specific transcript (XIST); Tsix transcript, mouse

The noncoding RNA Xist controls the initiation of random XCI

The importance of XCI is demonstrated by the fact that ablation of the master regulator of this process, Xist (X-inactive specific transcript), leads to female-specific lethality early in embryonic development in mice1,2. The X-linked Xist gene encodes an approximately 17 kb spliced and polyadenylated transcript that is essential for heterochromatin formation on the X chromosome from which it is transcribed1–4. In the embryo, XCI is random based on the parent-of-origin for the inactive X (Xi), such that female organisms are mosaic for which X chromosome is expressed. In vivo, random XCI is initiated in epiblast cells of the inner cell mass (ICM) of the blastocyst soon after implantation and, in vitro, upon induction of differentiation in mESCs, which are derived from epiblast cells of the pre-implantation blastocyst. Upon initiation of XCI, Xist is transcriptionally upregulated on the future Xi5,6. It has been suggested that the transcription factor Yin-Yang 1 (YY1) tethers Xist RNA to its site of transcription by binding directly to both Xist RNA and DNA7. The RNA then spreads and creates an ‘Xist RNA cloud’ demarcating the nuclear domain of the inactivating X yet the regulation of the release of Xist RNA from the Yy1 tether at the site of transcription is still unknown.

As Xist RNA molecules coat the X, they trigger transcriptional silencing with immediate exclusion of RNA polymerase II8. This is followed by loss of active chromatin marks and establishment of silencing chromatin marks, which occur in an ordered sequence of events and include, for example, trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) by the Polycomb complex PRC2, DNA methylation of promoter regions, and recruitment of the repressive histone variant macroH2A9. The result is the Xi is maintained late replicating in S phase through the lifetime of the organism. Xist transcription and coating of the Xi continues in somatic cells, with Xist RNA dissociating from the Xi in mitosis and re-coating the X in early G1 of the cell cycle10. Though Xist depletion during initiation of XCI leads to reversal of X chromosome silencing and heterochromatin formation, its deletion in somatic cells has only minor effects on Xi reactivation as the RNA acts synergistically with other repressive chromatin modifications that accumulate on the Xi during differentiation11,12.

Transcription and spreading of Xist RNA along the X is a prerequisite for silencing, which is not X-restricted as silencing can spread across X:autosome translocations and transgenic Xist can induce silencing of neighboring autosomal DNA12. The spread of Xist RNA-mediated silencing into autosomal regions is variable and has been proposed to correlate with the density of retrotransposons belonging to the family of long interspersed elements (L1)13. A recent report suggested that the silencing of X-linked L1s occurs prior to X-linked gene silencing and may promote the nucleation of heterochromatin. Conversely, specifically a subset of young L1 elements becomes transcribed upon Xist RNA coating and may help the local propagation of XCI14. In support of a functional role for L1 elements in XCI, the human X chromosome has a two-fold enrichment in L1 elements relative to autosomes15. Still it remains to be seen whether the behavior of these repetitive elements is a functionally important means of Xist-dependent facultative heterochromatin formation. In the following sections of the review we will discuss how Xist is regulated in pluripotent cells of the mouse.

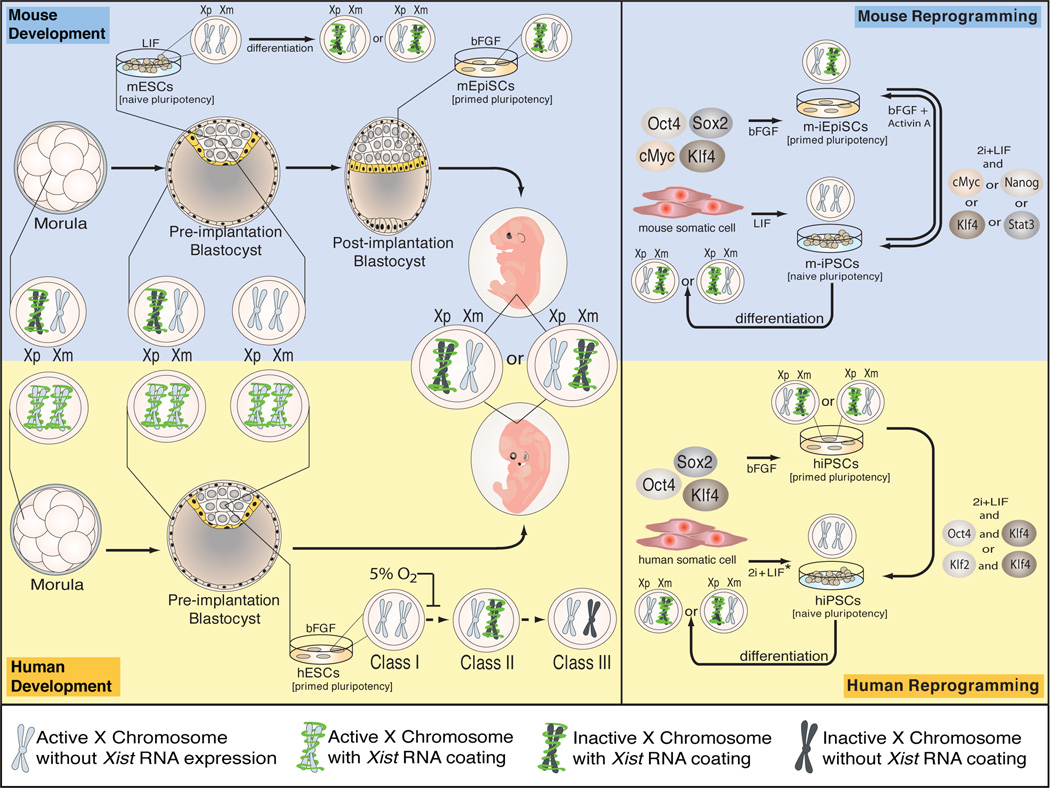

Acquisition of pluripotency in mouse is coupled to Xi reactivation

In the mouse, XCI occurs in two forms that differ in parent-of-origin effect and in the developmental timing of initiation. Imprinted XCI, where the paternal X chromosome (Xp) is inactivated, is established in the mouse pre-implantation embryo at the four-cell stage and occurs in all cells of the pre-implantation embryo (Fig1) 16–21. As the mid-blastocyst stage is reached (prior to implantation), imprinted XCI is reversed only in the subset of cells in the ICM that give rise to the epiblast, so that the cells that form the future embryo carry two active X chromosomes (XaXa) without Xist RNA coating16,18,21,22 (Fig1). Reactivation of the Xp is a prerequisite for subsequent random XCI in the epiblast upon implantation of the blastocyst16,18. In contrast, the imprinted form of XCI is maintained in the extraembryonic tissues.

Figure 1. Mouse and human XCI in development and reprogramming.

* The naïve human state can also be generated by overexpression of Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28 and appears to require continuous ectopic expression of reprogramming factors for stability.

Random and imprinted XCI differ in the molecular requirements for initiation and reactivation. In vivo evidence shows that, though Xist RNA coats the Xp, it is not required when imprinted XCI first occurs at the four-cell stage (as it is for random XCI). Rather, Xist RNA coating is needed to complete and stabilize the silencing of the imprinted Xi17,19,20. With respect to Xi reactivation, a recent study demonstrates that the reactivation of the imprinted Xp occurs in two steps, with induction of biallelic expression of X-linked genes preceding the disappearance of Xist RNA coating, in agreement with the notion that Xist RNA coating and silencing of the Xp are uncoupled at this point in development21. The mechanisms that lead to gene activation on the Xp and Xist silencing are still unclear but linked to the specification of the epiblast lineage, as pre-implantation embryos lacking the pluripotency transcription factor Nanog are unable to specify the epiblast lineage and do not induce the loss of Xist RNA coating and Polycomb protein enrichment on the Xi22. Nanog appears to be directly involved in the regulation of Xist because pre-implantation embryos with a genetically engineered overexpression of Nanog lose Xist RNA more rapidly, though without affecting the timing of Xp reactivation21. However, Nanog may not be sufficient for this effect on Xist as Nanog is already present in the Xi-bearing cells of the late morula and becomes restricted as the pluripotent XaXa epiblast lineage forms, indicating that other epiblast-linked mechanisms must synergize with Nanog to control Xist repression21,22.

It is now appreciated that X chromosome reactivation (XCR) also occurs during the experimentally induced acquisition of pluripotency through either transcription factor-induced reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), somatic cell nuclear transfer, or ESC/somatic cell fusion23–25. XCR during reprogramming of mouse somatic cells to iPSCs leads to loss of heterochromatic marks of the Xi and Xist repression, such that random XCI is observed upon differentiation of mouse (m) iPSCs, as in mESCs23 (Fig1). It has been demonstrated that XCR is a late event in miPSC reprogramming, occurring at around the time of pluripotency gene activation26, but insight into the mechanism and the events leading to Xi reactivation is still lacking. Nevertheless, the establishment of pluripotency both in vitro via reprogramming and in vivo during the establishment of the epiblast lineage in pre-implantation embryos, is coupled to XCR and Xist repression. Therefore, the XaXa state is a key attribute of the pluripotent state of mESCs and miPSCs.

Importantly, studies with a doxycycline-inducible Xist transgene have shown that Xist-dependent gene silencing is possible in undifferentiated male and female mESCs, but no longer after induction of differentiation or in somatic cells12. This observation illustrates that Xist function is context-dependent but not with respect to sex, as factors required for the silencing process are present in male and female undifferentiated mESCs. Since the active state of the X chromosomes must therefore be ensured by strong transcriptional repression of Xist in mESCs, one can view initiation of XCI upon differentiation of mESCs from the perspective of loss of Xist repression.

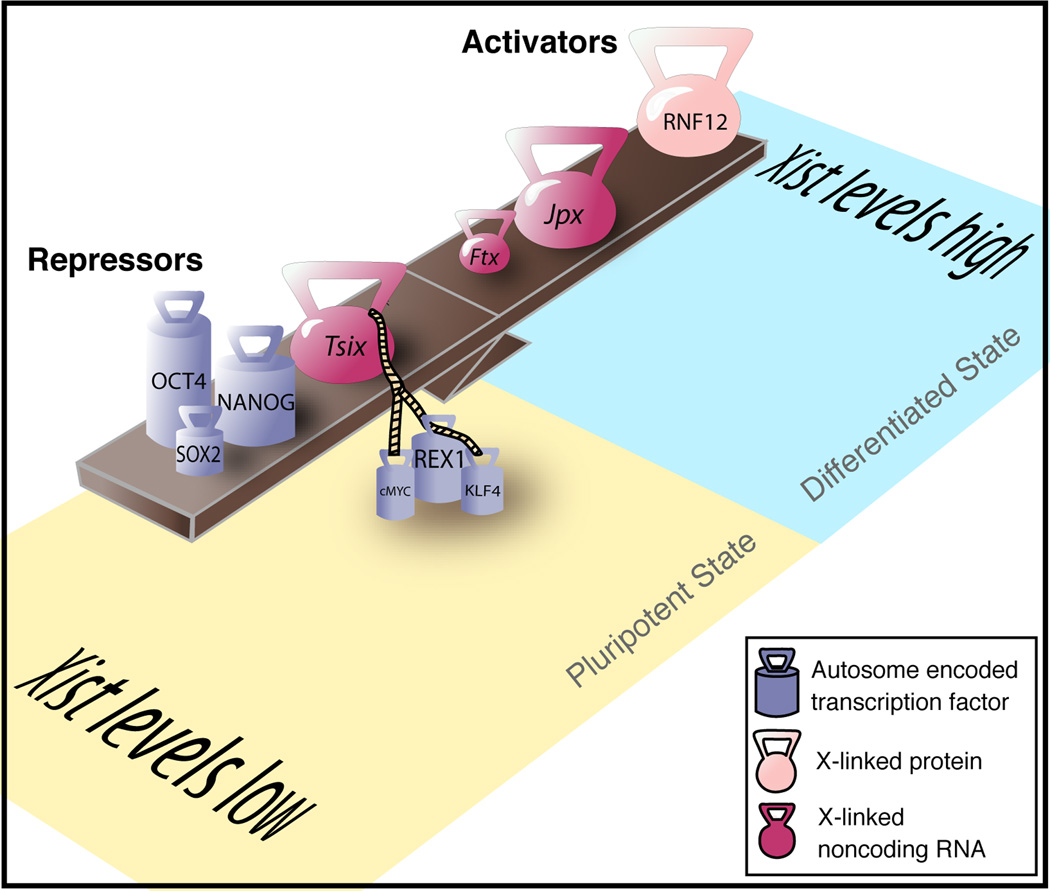

Xist is regulated by its antisense transcript Tsix

A major antagonizing factor to Xist in mESCs is another long noncoding RNA, Tsix, transcribed antisense to Xist specifically in mESCs and downregulated first on the Xi and then on the Xa during differentiation27 (Fig2). Loss of Tsix function on one of the two female X’s leads to slight upregulation of Xist transcript levels in undifferentiated mESCs and skewing of XCI towards the Tsix-deleted X upon differentiation28,29. These observations suggest that Tsix mainly regulates the monoallelic induction of Xist in the choice aspect of XCI. In support of this idea, live-cell imaging of differentiating female ESCs carrying X chromosomes tagged with a tetO array bound by a tetR-mCherry fusion confirmed a previously shown transient pairing of homologous Xist/Tsix regions of the two X chromosomes and demonstrated that this interaction is associated with exclusive deafening of the Tsix allele on the future Xi, which is proposed to allow upregulation of Xist30–32. Tsix antagonism of Xist requires transcription through the Xist locus and the mechanism is suggested to involve change in the chromatin structure around the Xist 5’ regulatory region33,34 Together these findings indicate that Tsix is not the only repressor of Xist in pluripotency and other factors must be involved in keeping Xist downregulated (Fig2).

Figure 2. Xist activators and repressors regulate initiation of XCI in mESCs.

Xist levels are low in undifferentiated mESCs before onset of XCI, because of pluripotency transcription factors repressing Xist directly or indirectly via Tsix. X-linked Xist activators increase Xist levels during differentiation, as they themselves are upregulated. Levels of autosomal factors such as pluripotency transcription factors decrease upon differentiation. Sizes and positions of weights are reflective of magnitude of Xist-up or downregulation phenotypes from experimental data (see text for discussion).

Pluripotency transcription factors directly repress XCI in ESCs

Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog form a transcription factor triad that is key to maintaining ESC identity by activating genes of the self-renewal program and repressing lineage commitment genes. An attractive hypothesis for how pluripotency is directly linked to Xist repression has come from a study that demonstrates binding of Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog to the first intron (intronl) of Xist in male and female mESCs and loss of this interaction upon differentiation35. Intriguingly, depletion of Nanog or Oct4 leads to inappropriate Xist upregulation in male mESCs or biallelic Xist upregulation in differentiating female mESCs35,36. It is still an open question whether specific binding at intron1 is at the heart of this XCI phenotype as these pluripotency transcription factors bind and regulate thousands of loci in the genome to maintain pluripotency. Mechanistically, the repressive function binding to intron1 has on Xist expression remains unclear, though one possibility is modification of the three-dimensional chromatin configuration within the Xist locus37.

Already one study reports no effect of heterozygous deletion of intron1 and a very subtle skewing of XCI to the intron1-deleted X chromosome late in differentiation38. Conceivably, synergism of pluripotency factor binding to intron1 of Xist as well as other regulatory regions could suppress XCI in mESCs. In line with this model, Tsix transcription, particularly transcriptional elongation, is dependent upon binding of the pluripotency transcription factors Rex1, Klf4, and cMyc, within a mini-satellite region of the regulatory region of the gene, and to a lesser extent by binding of Oct4 and Sox2, with the latter being somewhat debated 36,39. Thus, the pluripotency network may directly repress Xist and activate Tsix, which in turn contributes to the suppression of Xist and XCI (Fig2), an idea that could be tested with double knockout studies of intron1 and Tsix. Nevertheless, it may be challenging to pinpoint a role of pluripotency regulators in XCI especially as additional Xist activators and repressors are discovered (see below) and transactivation or repression of these other factors by pluripotency regulators may indirectly exert XCI effects.

XCI in differentiating female mouse ESCs is governed by a balance of Xist activators and repressors

The mechanisms governing Xist upregulation during XCI must also ensure that only one X is silenced in female cells during differentiation. In addition to the X:X pairing model described above, another model proposes that in random XCI every individual X has an independent probability to initiate silencing, and this probability is proportional to the X:autosome ratio, keeping one X active per diploid chromosome set40. Accordingly, repressors of XCI would be autosomally encoded and activators would be X-linked. In XX cells, the double dose of the activator would stimulate Xist upregulation and XCI on one X, and the reciprocal cis silencing of the X-linked activator gene would in turn protect the other X from inactivation40.

Rnf12, the first such characterized X-linked activator of XCI, resides ~500 kilobases from Xist, and encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase bearing a RING domain. In line with a role in the initiation of XCI, Rnf12 protein levels increase in differentiation and overexpression of Rnf12 stimulates ectopic XCI41. The heterozygous mutation of Rnf12 in female mESCs reduces the number of female cells undergoing XCI, however, it remains unclear if there is an essential requirement for Rnf12 in random XCI as the two published homozygous knockout strategies show contrasting results of delayed differentiation and dramatic loss of XCI38,41,42. These differences may be attributed to differentiation protocols as the late appearance of Xist RNA cloud-positive cells suggests a selective outgrowth of cells undergoing XCI independently of Rnf12. Gene expression profiling suggests Rnf12 acts on Xist, as Xist was the only transcript significantly downregulated in Rnf12 knockout cells38. Proteomic studies will likely be necessary to see if Rnf12 plays an indirect role in XCI through ubiquitylation targets.

Two additional noncoding RNAs have recently also been identified as X-linked Xist activators. Jpx, located upstream of Xist, escapes XCI and increases ~10-fold during mESC differentiation. Its heterozygous deletion leads to loss of XCI and subsequent cell death upon embryoid body differentiation of female XaXa mESCs43. These phenotypes can be rescued by an autosomal Jpx transgene, indicating that this novel gene can function in trans, which contrasts Xist and Tsix43. Strikingly, the double knockout of Jpx and Tsix completely restores XCI kinetics and viability and will be exciting to see how this observation and the mechanistic action of Jpx is explained43. Like Jpx, the noncoding transcript encoded by the neighboring Ftx gene is also transcriptionally upregulated with female mESC differentiation. Targeted deletion of Ftx suggests that its role is in controlling the chromatin structure of the Xist promoter44. It is tempting to speculate that continuous expression of these noncoding transcripts may be necessary for Xist itself to escape XCI. Rnf12 and Jpx are both bound by Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog in mESCs, suggesting that pluripotency factors could also act on XCI through these X-linked activators45.

In summary, the activation of Xist, repression of Tsix, and XCI during mESC differentiation depends on the downregulation of pluripotency factors and the expression of X-linked activators such as Rnf12, Jpx and Ftx, linking XCI status to the global pluripotency gene-expression network and ensuring sex-specificity of the developmental process.

XCI in human development

Studies on XCI in human pluripotent cells have been more limited in scope because of technical challenges in manipulating human pre-implantation embryos and the ethical challenges of acquiring them. However, studies of XCI in the human system remain essential because the XCI process appears to be different from that in mouse. For instance, human pre-implantation embryos demonstrate XIST expression from both X chromosomes and human full-term placentas have random, rather than imprinted XCI found in mouse46,47 (Fig1).

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) shows XIST activation as a transition from a pinpoint signal to a ‘XIST RNA cloud’ that can be appreciated in human female pre-implantation embryos as early as the eight-cell stage48. In one study, the majority of these XIST RNA-coated chromosomes show features of transcriptional silencing and enrichment of XIST-dependent repressive histone marks in the morula48. Contradictory results come from a more recent study which finds that the trophectoderm and the inner cell mass of both female and male human pre-implantation blastocysts carry active X chromosomes coated by XIST RNA49. The discrepancy between the two studies may be due to different culture conditions as well as hybridization efficiencies in the FISH procedure. Regardless, it appears there is no imprinted XCI in human embryogenesis, that human XCI has different developmental timing, and that XIST RNA coating of the X and XCI are uncoupled in early human embryos (Fig1).

Studies of additional factors involved in human XCI are limited to TSIX, which may not play a functional role in human cells. TSIX is transcribed in fetal cells, term placenta, and human ESCs but is truncated and lacks the CpG island essential for expression in mouse cells50,51. Since in human pre-Implantation development XIST expression appears to be uncoupled from XCI, TSIX-mediated regulation may be unnecessary. However, TSIX has not been studied in human pre-implantation blastocysts nor during initiation of XCI, therefore a potential role may have been missed52. Other modulators of XCI in mouse, namely JPX, FTX, and RNF12, have been mapped in the human genome but their functions have not yet been tested, mostly due to the lack of an in vitro system that allows their mechanistic dissection (see below).

Different XCI states are found in human ESCs

XCI state in human (h) ESCs is complicated by a gradual drift so that one hESC line can exhibit different states of XCI53–56. hESCs are grouped into three classes to describe the XCI states that are typically observed (Fig1)53. Class I hESCs are XaXa and upregulate XIST and undergo XCI upon differentiation, similar to mESCs. This class seems to be the most difficult to stabilize in vitro because they readily transition to class II, which have initiated XCI already in the undifferentiated state and carry a XIST-coated Xi. Class II hESCs often further transition to class III where the silent state of the Xi is largely maintained but XIST is lost from the Xi along with the XIST-dependent histone mark H3K27me3 which leads to partial reactivation of some Xi-linked genes54,56. XIST likely becomes silenced by methylation of its promoter region, and class III hESCs do not re-express XIST upon differentiation57,53. Given that both class I and III hESCs do not express XIST and lack an Xi enrichment of H3K27me3, extrapolating the XCI state solely on the basis of lack of XIST RNA FISH or H3K27me3 signal or even global gene expression data, has obfuscated the collective understanding of XCI in hESCs. Rather, characterization of XCI in hESC requires validation against the gold-standard assays of RNA FISH for mono- or biallelic expression of X-linked genes in addition to XIST.

hESCs derived and maintained in hypoxia, which is thought to better represent physiologic oxygen tension in development, preferentially remain in class I as demonstrated by RNA FISH for XIST and X-linked genes56. A switch to atmospheric oxygen tensions leads to irreversible transition to class II and subsequently to class III, strengthening the observation that female hESCs are unstable with respect to their XCI state (Fig1)56. It will be important to determine whether this fluctuating XCI status is indicative of global epigenetic instability in hESCs.

X chromosome state in human iPSCs

Like in the mouse, human (h) iPSCs are similar to their hESC equivalent based on functional assays of pluripotency, genome-wide expression and chromatin analysis, and XCI state. At early passage, hiPSCs are class II (XaXi with XIST RNA coating) which readily transition to class III as XIST RNA is lost from the Xi (Fig1)58. The same X chromosome is inactivated in all cells of a given hiPSC line reflecting the origin from a single somatic cell58,59. These results suggest the absence of Xi reactivation during human cell reprogramming and enable the generation of hiPSC lines expressing either only the Xm or Xp58. Such approaches have allowed for generation of genetically-matched hiPSC lines expressing either the mutant or wild-type X-linked gene MECP2 from fibroblasts of female patients with Rett syndrome59,60. However, complete skewing of XCI to one X chromosome occurs upon extended passaging of fibroblasts, preventing the generation of hiPSC lines with different X chromosomes inactivated59. Two contradictory studies that report Xi reactivation in a subset of hiPSC lines have not performed the single cell FISH analysis of X-linked gene expression, and the skewed XCI in neurons generated from hiPSCs in one of the studies would be consistent with the lack of Xi reactivation61,62. Nevertheless, these results do not exclude that different culture and reprogramming conditions could lead to XCR during hiPSC induction.

Naïve versus primed pluripotency

The different XCI states in mouse and human ESCs and iPSCs suggest that either there have been significant changes to XCI in mammalian evolution or, alternatively, that these XCI states are reflective of two different developmental states ‘suspended’ ex vivo through current ESC culturing techniques. Although pluripotent cells by definition can give rise to cells of all three germ layers, distinct states of pluripotency have recently been described in vitro, represented by mESCs and mouse epiblast stem cells (mEpiSCs). mESCs, derived from epiblast cells of pre-implantation blastocysts, are cultured in the presence of the cytokine LIF whereas mEpiSCs are obtained from post-implantation epiblast and cultured in the growth factor bFGF, in the absence of LIF. Since mEpiSCs express genes associated with early events in differentiation they are considered to be in the “primed” pluripotent state, whereas the typical mESC is in the “naïve” pluripotent state63. mEpiSCs resemble class II hESC/iPSCs in many aspects including their flat colony morphology, bFGF culture requirement, and the presence of an Xi coated by Xist RNA and enriched for H3K27me3 and the Polycomb protein Ezh264–66. XiXa mEpiSCs can also be generated from pre-implantation blastocysts cultured with bFGF (just like hESCs), differentiated from mESCs with bFGF and Activin A, and obtained via reprogramming of fibroblasts with Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and cMyc in bFGF-containing media as opposed to LIF66–68 (Fig1B). Together, the parallels between hESCs and mEpiSCs suggest that the culture of human pluripotent cells has been optimized for the primed state and not for the naïve state.

More research is necessary to molecularly define whether mEpiSCs exhibit different types of XCI states as do hESCs/iPSCs. Interestingly, it appears that compared with mouse fibroblasts, the form of XCI in mEpiSCs is a developmental intermediate and more labile with regard to reactivation based on studies transplanting nuclei into xenopus germinal vesicles65. In this reprogramming system, the Xi of female mEpiSCs is receptive to nuclear reprogramming whereas the mouse fibroblast macroH2A-enriched Xi is resistant65.

Molecular manipulation can transition mEpiSCs to the naïve pluripotent state and these approaches have been extended to the human system to generate XaXa hESCs and hiPSCs. The reprogramming of mEpiSCs to an mESC-like state is achieved through a combination of ectopic expression of any one of the transcription factors Klf4, cMyc, Stat3 or Nanog and addition of LIF and 2i (a combination of two small molecules inhibiting GSK3β in the Wnt signaling pathway and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, which is thought to promote naïve pluripotency) (Fig1)22,66,69–71. A subsequent study applied this approach to hESCs and found similar requirements for acquisition of naïve pluripotency in primed hESCs when Klf4 and Klf2 or Klf4 and Oct4 are overexpressed72. Prolonged maintenance of the naïve human pluripotent state appears to depend on constitutive overexpression of the reprogramming factors, indicating that the naïve human state is metastable72,59. As expected from the mouse system, naïve human pluripotent stem cells are XaXa without XIST expression, and diverge from primed pluripotent cells in both culture requirements and molecular profile as determined by gene expression microarrays72. As in mouse, XIST is re-expressed and random XCI initiated upon differentiation of naïve human cells 59,72. The derivation of XaXa human pluripotent cells, either in the primed state under hypoxic conditions or in the naïve state, should in the future allow the modeling of initiation of XCI ex vivo.

Yet, the relevance of modeling human XCI ex vivo for the XCI process occurring during human embryonic development is still unclear. During derivation and culture of human pluripotent cells, the XCI state diverges from that described for pre-implantation embryos, as the XaXa pattern with biallellic XIST coating of pre-implantation embryos has not been detected in cell cultures ex vivo. Therefore more studies are warranted but, with the approaches of these recent studies, we can already begin to define the molecular interplay of pluripotency and XCI, akin to the mouse system, and extend these findings to optimize reprogramming to pluripotency.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge that many important studies in the field of XCI are not mentioned due to space limitations.

Grants acknowledgements: KP is supported by the NIH Director’s Young Innovator Award (DP2OD001686), a CIRM Young Investigator Award (RN1-00564), and by the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA, AM by USPHS National Research Service Award GM07104, and SP by CIRM TG2-01169. AM and KP are supported by the Iris Cantor-UCLA Women’s Health Center.

Footnotes

Author contribution summary:

Alissa Minkovsky: Manuscript writing, other (equal contribution to Sanjeet Patel)

Sanjeet Patel: Manuscript writing, other (equal contribution to Alissa Minkovsky)

Kathrin Plath: Manuscript writing, financial support, final approval of manuscript

No disclaimers

Contributor Information

Alissa Minkovsky, University of California Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine, Department of Biological Chemistry.

Sanjeet Patel, University of California Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine, Molecular Biology Institute, Department of Surgery, Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research.

Kathrin Plath, University of California Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine, Department of Biological Chemistry, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Molecular Biology Institute, Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research.

Bibliography

- 1.Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, et al. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature. 1996;379(6561):131–137. doi: 10.1038/379131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marahrens Y, Panning B, Dausman J, et al. Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes and Development. 1997;11(2):156–166. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockdorff N, Ashworth A, Kay GF, et al. Conservation of position and exclusive expression of mouse Xist from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;351(6324):329–331. doi: 10.1038/351329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CJ, Ballabio A, Rupert JL, et al. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation center is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;349(6304):38–44. doi: 10.1038/349038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun BK, Deaton AM, Lee JT. A transient heterochromatic state in Xist preempts X inactivation choice without RNA stabilization. Molecular Cell. 2006;21(5):617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panning B, Jaenisch R. DNA hypomethylation can activate Xist expression and silence X-linked genes. Genes and Development. 1996;10(16):1991–2002. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon Y, Lee JT. YY1 tethers Xist RNA to the inactive X nucleation center. Cell. 2011;146(1):119–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaumeil J, Le Baccon P, Wutz A, et al. A novel role for Xist RNA in the formation of a repressive nuclear compartment into which genes are recruited when silenced. Genes and Development. 2006;20(16):2223–2237. doi: 10.1101/gad.380906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow J, Heard E. X inactivation and the complexities of silencing a sex chromosome. Current Option in Cell Biology. 2009;21(3):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemson CM, McNeil JA, Willard HF, et al. XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at interphase: evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome structure. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;132(3):259–275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csankovszki G, Nagy A, Jaenisch R. Synergism of Xist RNA, DNA methylation, and histone hypoacetylation in maintaining X chromosome inactivation. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;153(4):773–784. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wutz A. A shift from reversible to irreversible X inactivation is triggered during ES cell differentiation. Molecular Cell. 2000 Apr;5(4):695–705. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyon MF. X-chromosome inactiavtion: a repeat hypothesis. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 1998;80(1–4):133–137. doi: 10.1159/000014969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow JC, Ciaudo C, Fazzari MJ, et al. LINE-1 Activity in Facultative Heterochromatin Formation during X Chromosome Inactivation. Cell. 2010;141(6):956–969. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey JA, Carrel L, Chakravarti A, Eichler EE. Molecular evidence for a relationship between LINE-1 elements and X chromosome inactivation: the Lyon repeat hypothesis. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences. 200;97(12):6634–6639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okamoto I, Otte A, Allis C, et al. Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X inactivation during early mouse development. Science. 2004;303(5658):644–649. doi: 10.1126/science.1092727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalantry S, Purushothaman S, Bowen RB, et al. Evidence of Xist RNA-independent initiation of mouse imprinted X-chromosome inactivation. Nature. 2009;460(7255):647–651. doi: 10.1038/nature08161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mak W, Nesterova TB, de Napoles M, et al. Reactivation of the paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Science. 2004;303(5658):666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1092674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namekawa SH, Payer B, Huynh KD, et al. Two-Step Imprinted X Inactivation: Repeat versus Genic Silencing in the Mouse. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2010;30(13):3187–3205. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00227-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrat C, Okamoto I, Diabangouaya P, et al. Dynamic changes in paternal X-chromosome activity during imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(13):5198–5203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810683106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams LH, Kalantry S, Starmer J, et al. Transcription precedes loss of Xist coating and depletion of H3K27me3 during X-chromosome reprogramming in the mouse inner cell mass. Development. 2011;138(10):2049–2057. doi: 10.1242/dev.061176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva J, Nichols J, Theunissen TW, et al. Nanog Is the Gateway to the Pluripotent Ground State. Cell. 2009;138(4):722–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maherali N, Sridharan R, Xie W, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eggan K, Akutsu H, Hochedlinger K, et al. X-Chromosome inactivation in cloned mouse embryos. Science. 2000 Nov 24;290(5496):1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tada M, Takahama Y, Abe K, et al. Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Current Biology. 2001;11(19):1553–1558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault DT, Hochedlinger K. Direct molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JT, Davidow LS, Warshawsky D. Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nature Genetics. 1999;21(4):400–404. doi: 10.1038/7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JT, Lu N. Targeted mutagenesis of Tsix leads to nonrandom X inactivation. Cell. 1999;99(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sado T, Wang Z, Sasaki H, et al. Regulation of imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice by Tsix. Development. 2001;128(8):1275–1286. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masui O, Bonnet I, Le Baccon P, et al. Live-Cell Chromosome Dynamics and Outcome of X Chromosome Pairing Events during ES Cell Differentiation. Cell. 2011;145(3):447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu N, Tsai C, Lee J. Transient homologous chromosome pairing marks the onset of X inactivation. Science. 2006;311(5764):1149–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.1122984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bacher C, Guggiari M, Brors B, et al. Transient colocalization of X-inactivation centres accompanies the initiation of X inactivation. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8(3):293–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sado T, Hoki Y, Sasaki H. Tsix silences Xist through modification of chromatin structure. Developmental Cell. 2005;9(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarro P, Pichard S, Ciaudo C, et al. Tsix transcription across the Xist gene alters chromatin conformation without affecting Xist transcription: implications for X-chromosome inactivation. Genes and Development. 2005;19(12):1474–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.341105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navarro P, Chambers I, Karwacki-Neisius V, et al. Molecular coupling of Xist regulation and pluripotency. Science. 2008;321(5896):1693–1695. doi: 10.1126/science.1160952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donohoe ME, Silva SS, Pinter SF, et al. The pluripotency factor Oct4 interacts with Ctcf and also controls X-chromosome pairing and counting. Nature. 2009;460(7251):128–132. doi: 10.1038/nature08098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai C, Rowntree R, Cohen D, et al. Higher order chromatin structure at the X-inactivation center via looping DNA. Developmental Biology. 2008;319(2):416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barakat TS, Gunhanlar N, Pardo CG, et al. RNF12 activates Xist and is essential for X chromosome inactivation. Plos Genetics. 2011;7(1):e1002001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarro P, Oldfield A, Legoupi J, et al. Molecular coupling of Tsix regulation and pluripotency. Nature. 2010;468(7322):457–460. doi: 10.1038/nature09496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monkhorst K, Jonkers I, Rentmeester E, et al. X inactivation counting and choice is a stochastic process: evidence for involvement of an X-linked activator. Cell. 2008;132(3):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jonkers I, Barakat T, Achame E, et al. RNF12 is an X-Encoded dose-dependent activator of X chromosome inactivation. Cell. 2009;139(5):999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin J, Bossenz M, Chung Y, et al. Maternal Rnf12/RLIM is required for imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice. Nature. 2010;467(7318):977–981. doi: 10.1038/nature09457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian D, Sun S. The Long Noncoding RNA, Jpx, Is a Molecular Switch for X Chromosome Inactivation. Cell. 2010;143(3):390–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chureau C, Chantalat S, Romito A, et al. Ftx is a non-coding RNA which affects Xist expression and chromatin structure within the X-inactivation center region. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20(4):705–718. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133(6):1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daniels R, Zuccotti M, Kinis T, et al. XIST Expression in Human Oocytes and Preimplantation Embryos. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 1997;61(1):33–39. doi: 10.1086/513892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Mello J, de Araújo É, Stabellini R, et al. Random X Inactivation and Extensive Mosaicism in Human Placenta Revealed by Analysis of Allele-Specific Gene Expression along the X Chromosome. Plos One. 2010;5(6):e10947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Berg IM, Laven JSE, Stevens M, et al. X Chromosome Inactivation Is Initiated in Human Preimplantation Embryos. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2009;84(6):771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okamoto I, Patrat C, Thépot D, et al. Eutherian mammals use diverse strategies to initiate X-chromosome inactivation during development. Nature. 2011;472(7343):370–374. doi: 10.1038/nature09872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Migeon BR, Chowdhury AK, Dunston JA, et al. Identification of TSIX, encoding an RNA antisense to human XIST, reveals differences from its murine counterpart: implications for X inactivation. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;69(5):951–960. doi: 10.1086/324022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Migeon BR, Lee CH, Chowdhury AK, et al. Species differences in TSIX/Tsix reveal the roles of these genes in X-chromosome inactivation. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71(2):286–293. doi: 10.1086/341605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Migeon BR. Is Tsix repression of Xist specific to mouse? Nature Genetics. 2003;33(3):337. doi: 10.1038/ng0303-337a. author reply 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silva S, Rowntree R, Mekhoubad S, et al. X-chromosome inactivation and epigenetic fluidity in human embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(12):4820–4825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712136105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen Y, Matsuno Y, Fouse SD, et al. X-inactivation in female human embryonic stem cells is in a nonrandom pattern and prone to epigenetic alterations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(12):4709–4714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712018105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dvash T, Lavon N, Fan G. Variations of X Chromosome Inactivation Occur in Early Passages of Female Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Plos One. 2010;5(6):e11330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lengner CJ, Gimelbrant AA, Erwin JA, et al. Derivation of Pre-X Inactivation Human Embryonic Stem Cells under Physiological Oxygen Concentrations. Cell. 2010;141(5):872–883. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dvash T, Fan G. Epigenetic regulation of X-inactivation in human embryonic stem cells. Epigenetics. 2009;4(1):19–22. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.1.7438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tchieu J, Kuoy E, Chin MH, et al. Female Human iPSCs Retain an Inactive X Chromosome. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(3):329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pomp O, Dreesen O, Leong D, et al. Unexpected X Chromosome Skewing during Culture and Reprogramming of Human Somatic Cells Can Be Alleviated by Exogenous Telomerase. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheung AYL, Horvath LM, Grafodatskaya D, et al. Isolation of MECP2-null Rett Syndrome patient hiPS cells and isogenic controls through X-chromosome inactivation. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20(11):2103–2115. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marchetto MCN, Carromeu C, Acab A, et al. A Model for Neural Development and Treatment of Rett Syndrome Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell. 2010;143(4):527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim K-Y, Hysolli E, Park IH. Neuronal maturation defect in induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Rett syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(33):1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018979108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and Primed Pluripotent States. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tesar P, Chenoweth J, Brook F, et al. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7150):196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pasque V, Gillich A, Garrett N, et al. Histone variant macroH2A confers resistance to nuclear reprogramming. The Embo Journal. 2011;30(12):2373–2387. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo G, Yang J, Nichols J, et al. Klf4 reverts developmentally programmed restriction of ground state pluripotency. Development. 2009;136(7):1063–1069. doi: 10.1242/dev.030957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Najm FJ, Chenoweth JG, Anderson PD, et al. Isolation of epiblast stem cells from preimplantation mouse embryos. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(3):318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han DW, Greber B, Wu G, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into epiblast stem cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;13(1):66–71. doi: 10.1038/ncb2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bao S, Tang F, Li X, et al. Epigenetic reversion of post-implantation epiblast to pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;461(7268):1292–1295. doi: 10.1038/nature08534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hanna J, Markoulaki S, Mitalipova M, et al. Metastable Pluripotent States in NOD-Mouse-Derived ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang J, Oosten ALV, Theunissen TW, et al. Stat3 Activation Is Limiting for Reprogramming to Ground State Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(3):319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hanna J, Cheng AW, Saha K, et al. Human embryonic stem cells with biological and epigenetic characteristics similar to those of mouse ESCs. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(20):9222–9227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004584107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]