Abstract

Reduced expression of the metastasis suppressor NM23-H1 is associated with aggressive forms of multiple cancers. Here, we establish that NM23-H1 (termed H1 isoform in human, M1 in mouse) and two of its attendant enzymatic activities, the 3′-5′ exonuclease and nucleoside diphosphate kinase, are novel participants in the cellular response to UV radiation (UVR)-induced DNA damage. NM23-H1 deficiency compromised the kinetics of repair for total DNA polymerase-blocking lesions and nucleotide excision repair of (6-4) photoproducts in vitro. Kinase activity of NM23-H1 was critical for rapid repair of both polychromatic UVB/UVA (290-400 nm)- and UVC (254 nm)-induced DNA damage, while its 3′-5′ exonuclease activity was dominant in the suppression of UVR-induced mutagenesis. Consistent with its role in DNA repair, NM23-H1 rapidly translocated to sites of UVR-induced (6-4) photoproduct DNA damage in the nucleus. In addition, transgenic mice hemizygous-null for nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 exhibited UVR-induced melanoma and follicular infundibular cyst formation, and tumor-associated melanocytes displayed invasion into adjacent dermis, consistent with loss of invasion-suppressing activity of NM23 in vivo. Taken together, our data demonstrate a critical role for NM23 isoforms in limiting mutagenesis and suppressing UVR-induced melanomagenesis.

Keywords: metastasis suppressor, melanoma, NM23, DNA damage, nucleotide excision repair

Introduction

Metastasis suppressor genes inhibit multiple steps of metastasis in human cancer (1, 2). The first metastasis suppressor gene to be described was nm23-m1, initially identified by its diminished expression in metastatic melanoma and breast carcinoma cell lines (3). While metastasis suppressor function of nm23-h1 was validated in multiple settings (4, 5), its contribution to suppression of tumor initiation and progression is not well-understood. Low NM23 expression in primary melanomas is correlated with poor clinical outcome, however, suggesting relevance of NM23 deficiency to initiation and/or progression in earlier stages of this tumor (6-8).

NM23-H1 possesses nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) activity, which maintains balance in intracellular nucleotide pools through transfer of γ-phosphates between nucleoside triphosphates and diphosphates (9). NM23-H1 also exhibits histidine protein kinase (hisK) activity (10) with the kinase suppressor of ras representing a relevant substrate (11). Nuclease activity was also described for the NM23-H2 isoform (12, 13), followed by our characterization of a 3′-5′ exonuclease function for the NM23-H1 isoform (14). 3′-5′ exonucleases execute stepwise excision of damaged or mispaired nucleotides during DNA replication and repair (15), suggesting a possible role for NM23-H1 in these processes as well. We recently demonstrated that ablation of the nm23 homolog in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ynk1, results in compromised DNA repair and increased mutation rates in response to UVR and etoposide treatment (16). More recently, we showed that mutations disrupting the 3′-5′ exonuclease activity of NM23-H1 result in reduced metastasis suppressor capacity in vivo (17). These observations suggest loss of NM23-H1 expression may drive the genesis and progression of melanoma. Herein, 3′-5′ exonuclease and kinase activities of NM23-H1 are shown to be required for DNA repair and maintenance of genomic fidelity in human melanoma and mouse cells. In addition, transgenic mice harboring hemizygous deficiencies in the nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 genes are susceptible to UVR-induced melanomagenesis, consistent with a key role for NM23 proteins in repair of UVR-induced DNA damage.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, stable transfection and UVR exposure

The human melanoma cell line WM793 is derived from a vertical growth phase (VGP) lesion (18, 19). WM793 and stably-transfected variant lines were cultured in MCDB media (Sigma) supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2, 2.5 μg insulin and 2 % fetal calf serum (Invitrogen). Procedures for stable transfection of melanoma cell lines have been described previously (17). DNA short tandem repeat (STR) profiling (Genetica DNA Laboratories) of the WM793 cells used in this study confirmed identity at nine genetic loci, including the sex identity locus amelogenin, with the WM793 profile established by the American Type Culture Collection.

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from C57/BL6 mouse embryos (13.5 day gestation), as well as syngeneic strains harboring either a single inactivating deletion in the nm23-m1 locus alone (M1 is the mouse homolog of the human H1 isoform; (20) or a tandem deletion of both the nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 loci (21)). MEFs were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Melanocyte cultures were established from the epidermal skin layer from day 4 neonatal mice and cultivated as previously described (22). UVR was delivered to cell cultures with lamps (UVP, Upland) emitting a spectral output in the UVB/A (60 % UVB, 290–320 nm; 40 % UVA, 320–400 nm; <1 % UVC, 250–290 nm) or UVC (254 nm) range.

DNA damage and repair assays

Cells were irradiated with either 15 J/m2 UVB/A or 5 J/m2 UVC following 24 h in reduced serum medium (0.5%). Presence of UVR-induced DNA polymerase-blocking lesions was assessed using XL-PCR, which detects the total of a variety of polymerase-blocking lesions, such as base modifications, photoproducts, abasic sites and strand breaks (23). Repair of a 10.4 kb fragment of the hprt gene was assessed by PCR as described (23). Efficiency of PCR amplification between damage and control samples was used to calculate repair at each time point as described (16). Removal of pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidone photoproducts (6-4 photoproducts) and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) was measured by immuno-slot blot assay (24). Equal loading of DNA was confirmed by DAPI (Invitrogen) staining (25).

Localized UVR exposure, in situ detergent extraction and immunofluorescence

A clone of the WM793 melanoma cell line (793H1-FL8) was created to express NM23-H1 with a C-terminal 3X FLAG peptide sequence by stable transfection, as described (17). To acheive localized UV irradiation, cells were grown on plastic chamber slides (Lab-Tek), media was aspirated, and UVC (50J/m2) applied through sterile UV-absorbing polycarbonate with 5 μm pores (Millipore) (26). The membrane was removed and cells were either processed immediately, or medium was replaced and DNA repair allowed for the indicated periods. Cell extraction was carried out in situ by 2 washes of 0.1% Nonidet P-40 for 10 min on ice, followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4 °C. Antibodies directed to FLAG (anti-FLAG; Sigma), (6-4) photoproducts (anti-(6-4) photoproduct; Cosmo. Bio.), and secondary antibodies conjugated to DyLight Fluors (DyLight 549 and 488; Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used for immunodetection. Fluorescence images were obtained using a Leica SP5 inverted confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Mutation frequency in the hprt gene

Acquired resistance of cells to 6-thioguanine (6-TG) is conferred primarily by mutations within the hprt locus (27), and quantified as the number of 6-TG-resistant (6-TGr) colonies obtained after selection. Frequencies of spontaneous and UVR-induced hprt mutations in WM793-derived cell lines expressing wild-type and mutant variants of NM23-H1 were measured as described (27, 28). WM793-derived cell lines were seeded at 100 cells per well in a 6-well plate, with each line plated with twelve replicates, six of which were used for analysis of colony forming efficiency and six for characterization of mutation spectra (Supplemental Methods). Cells were exposed to either UVB/A (5 J/m2) or sham-treated, then grown in complete MCDB medium supplemented with 40 μM 6-TG. Colonies were counted at 28 days following initial treatment, with colony-forming efficiency derived as the number of 6-TG-resistant colonies as a percentage of initial plating density.

UVB/A radiation of mice and melanoma surveillance

Protocols for use of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky (Protocol 00801M2004). Parental C57/BL6 (n=15) and the strain harboring hemizygotic deletion of the nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 loci (m1−/+:m2−/+) (n=12) were subjected to an erythematous exposure of UVB/A radiation at postnatal day five. A single dose of 4000 J/m2 was administered with lamps emitting a spectral output in the 290-400 nm range (UVB/A) (UVP, Upland). Irradiated mice displayed skin reddening and occasional superficial desquamation, but without morbidity or mortality. Tumor incidence and growth rate were monitored weekly, with caliper measurements (29) initiated at first appearance of a raised lesion. Mice were euthanatized 12 months-post UVR treatment and skin lesions analyzed by standard histopathology and immunohistochemical methods. Specimens were stained for either melanin using the Fontana-Masson procedure (American MasterTech) or dopachrome tautomerase (Dct) using the antibody anti-PEP8 (1:200) (generously provided by Vince Hearing, National Cancer Institute), and developed with the Vectastain ABC kit with ImmPACT NovaRED (Vector Laboratories). Genotyping was performed using published protocols (21).

Statistical analyses

Values are reported as means ± SEM. All analyses, including Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t test and two-way ANOVA, were conducted with SPSS software (SPSS Inc).

RESULTS

NM23 expression promotes repair of UVR-induced DNA lesions in transformed and non-transformed cells

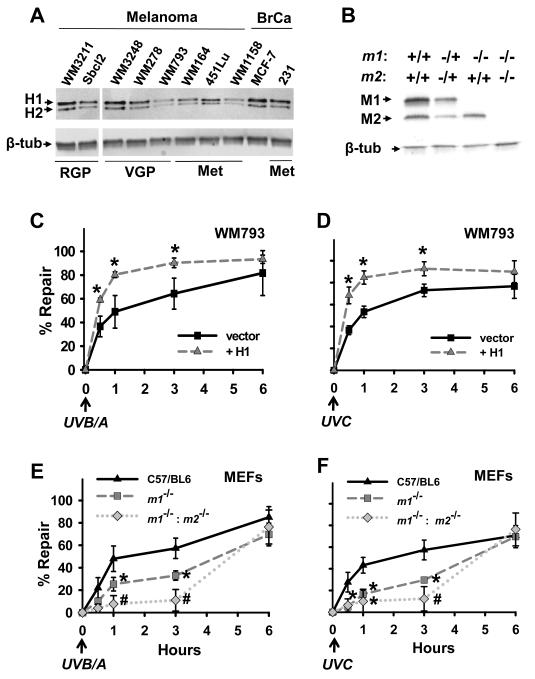

Impact of NM23-H1 expression on repair of UVR-induced DNA damage was measured initially in the NM23-deficient, VGP-derived melanoma cell line WM793 (19). Low NM23 expression was confirmed by comparison with multiple melanoma and breast cancer cell lines representing various stages of progression (Fig. 1A). The impact of nm23 gene ablation on DNA repair was also assessed in MEFs obtained from mice harboring either a single inactivating deletion in the nm23-m1 locus alone (m1 is the mouse homolog of the human h1 isoform) or a tandem deletion of both the nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 loci (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

NM23 deficiency compromises UVR-induced DNA repair in WM793 melanoma cells and MEFs. A, Relative NM23 protein expression was examined in multiple melanoma and breast cancer cell lines and B, MEFs from the parent C57/BL6, m1−/− or m1−/−: m2−/− strains. C, UVB/A (15 J/m2) or D, UVC (5 J/m2)-induced DNA damage repair was assessed in WM793 variants without (vector) or with NM23-H1 overexpression (+H1). E, UVB/A-induced or F, UVC-induced DNA damage repair was determined in MEFs from the parent C57/BL6, m1−/− or m1−/−: m2−/− strains. Values not sharing a common symbol are significantly different to control as determined by two-way ANOVA (P < 0.05; n=3-4).

XL-PCR assay demonstrated slow DNA repair after UVB/A (Fig. 1C) and UVC (Fig. 1D) exposure of vector-transfected WM793 cells (t1/2 ~ 1 hour), with forced expression of wild-type NM23-H1 accelerating repair (t1/2 ~ 25 minutes; P < 0.05). MEFs bearing a homozygous deletion of the nm23-m1 locus exhibited delayed repair of lesions obtained from UVB/A (Fig. 1E) and UVC (Fig. 1F) exposure (t1/2 ~ 4.3 and 4.5 hours, respectively) compared to MEFs from parental C57/BL6 mice (t1/2 ~ 1.4 and 2.3 hours, respectively). Tandem deletion of nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 (21) resulted in an additional delay, up to ~ 5.2 hours post-UVC exposure (P < 0.05). These data indicate an essential contribution for the H1/M1 isoform of NM23 in the early repair response to UVR-generated DNA damage, and probably an additional contribution from the H2/M2 isoform.

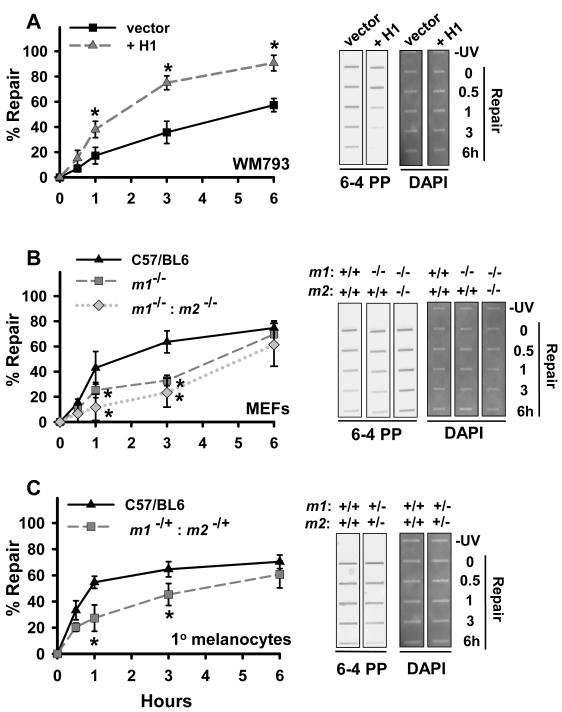

NM23-H1 and the mouse homolog NM23-M1 promote nucleotide excision repair-mediated removal of (6-4) photoproducts

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is the principal pathway for repair of UVR-generated (6-4) photoproducts and CPDs (30). To quantify the contribution of NM23-H1 to NER-mediated repair of these UVR-induced lesions, we measured removal of (6-4) photoproducts and CPDs by a immuno-slot blot approach (24). (6-4) photoproduct repair was relatively slow in control-transfected WM793 cells (t1/2 ~ 4.7 hours; Table 1 and Fig. 2A), and significantly accelerated by forced NM23-H1 expression (t1/2 ~ 1.5 hours; P ≤ 0.05). MEFs obtained from C57/BL6 mice (Table 1 and Fig. 2B) exhibited significantly faster repair (t1/2 ~1.7 hours; P ≤ 0.05) than MEFs harboring either a single homozygous deletion of the nm23-m1 locus (Table 1; t1/2 ~4.3 hours; P ≤ 0.05) or concurrent homozygous deletions of both the nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 loci (t1/2 ~4.8 hours; P ≤ 0.05). Melanocytes isolated from mice with hemizygous deficiency at both the m1 and m2 loci (Table 1 and Fig. 2C) also exhibited reduced repair of (6-4) photoproducts compared to wild-type melanocytes (t1/2 ~0.9 hours versus 4 hours; P ≤ 0.05) (Table 1 and Fig. 2C). CPD repair was much slower than that of (6-4) photoproducts in all cell types (Supplemental Fig. 1A-C), and NM23-H1 status had no impact on the rate of CPD removal.

Table 1.

NM23 deficiency compromises UVR-induced DNA repair

| Polymerase-blocking lesions |

6-4 photoproducts |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| UVB/A | UVC | UVC | |

| repair half-time*, minutes | |||

| Melanocytes | |||

| C57/BL6 | n.d.‡ | n.d. | 55 ± 17a |

| M1+/− : M2 +/− | n.d. | n.d. | 248 ± 36b |

| MEFs | |||

| C57/BL6 | 86 ± 19a | 137 ± 13a | 102±24a |

| M1−/− : M2 +/+ | 263 ± 28b | 267 ± 9b | 262 ± 18‡ |

| M1−/− : M2 −/− | 293 ± 31b | 312 ± 17b | 285 ± 31b |

| WM793 melanoma | |||

| Vector | 59 ± 13a | 63 ± 7a | 283 ± 36a |

| Wild-type H1 | 24 ± 9b | 27 ± 13b | 90 ± 26b |

| E5A (kin+ : exo−) | 51 ± 8a | 38 ± 9b | 112 ± 19b |

| K12Q (kin− : exo−) | 62 ± 15a | 72 ± 22a | 295 ± 28a |

| P96S (kin− : exo+) | 33 ± 13a,b | 57 ± 9a | 291 ± 16a |

| H118F (kin− : exo+) | 49 ± 11a | 49 ± 6a | 203 ± 11a |

Repair efficiencies are expressed as time taken in minutes to repair 50% of initial damage and expressed as mean ± SEM from at least 3 replicate measurements.

n.d., not determined

means within a cell type not bearing a common superscript are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05), as determined by two-way ANOVA and mean separation.

means within a cell type not bearing a common superscript are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05), as determined by two-way ANOVA and mean separation.

Figure 2.

NM23 deficiency compromises NER removal of (6-4) photoproducts. (6-4) photoproduct content in genomic DNA was measured by immunoslot blot analysis following UVC exposure (5 J/m2). A, WM793 variants without (vector) or with NM23-H1 overexpression (+H1), B, MEFs from the parent C57/BL6, m1−/− or m1−/−: m2−/− strains, and C, primary murine melanocytes cultured from pC57/BL6 or the hemizygous-null m1−/+: m2−/+ strain. Values not sharing a common symbol are significantly different to control as determined by two-way ANOVA (P < 0.05; n=3-4). Representative immunoslot blot images of (6-4) photoproducts are shown to the right of corresponding graphs in panels A-C, with DAPI staining to demonstrate equal loading of total genomic DNA.

3′-5′ exonuclease and kinase activities of NM23-H1 are required for prompt repair of UVB/A-induced DNA damage

To measure relative contributions of the 3′-5 exonuclease and kinase activities of NM23-H1 to repair of DNA lesions induced by UVB/A, a panel of WM793-derived cell lines stably expressing enzymatically-defective variants of NM23-H1 was employed (Supplemental Fig. 2). These cell lines consisted of mixed transfectant populations (10 – 100 independent colonies per cell line) to minimize effects of clonal phenotypic variation (14, 17). The NM23-H1 mutants consisted of E5A, which is deficient in 3′-5′ exonuclease activity but exhibits normal NDPK and hisK function (EXO−, kinase+), K12Q, which is defective in both activities (EXO−, kinase−), P96S, which is partially kinase-deficient (EXO−/+, kinase−/+), and H118F, which exhibits total loss in kinase activity but normal 3′-5′ exonuclease activity (EXO+, kinase−).

As determined using the XL-PCR assay, each of the mutants exhibited some degree of delayed repair of UVB/A-induced damage relative to wild-type NM23-H1 (Table 1) The 3′-5′ exonuclease-deficient mutants E5A (t1/2 ~ 51 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 3A) and K12Q (t1/2 ~ 62 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 3B) displayed delayed repair relative to wild-type NM23-H1 over the first three hours of repair. The kinase-deficient mutants P96S (t1/2 ~ 33 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 3C) and H118F (t1/2 ~ 49 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 3D) exhibited delayed repair that was less marked than with E5A and K12Q, but significantly different from wild-type. These data strongly suggest contributions of both the 3′-5′ exonuclease and kinase functions of NM23-H1 to repair of UVB/A-induced lesions.

Kinase activity of NM23-H1, but not its 3′-5′ exonuclease function, promotes nucleotide excision repair of (6-4) photoproducts

XL-PCR assay of UVC-induced lesions, consisting primarily of (6-4) photoproducts and CPDs, showed the E5A variant (t1/2 ~ 38 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 4A) to have repair activity that was not different from that of wild-type NM23-H1, suggesting lack of involvement of the 3′-5′ exonuclease function in the removal of these lesions. However, significantly delayed repair in the kinase-deficient mutants K12Q (t1/2 ~ 72 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 4B), P96S (t1/2 ~ 57 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 4C) and H118F (t1/2 ~ 49 minutes; Supplemental Fig. 4D) relative to wild-type NM23-H1-transfected cells were observed (Table 1), indicating involvement of the kinase activity in NER proficiency. Repair activity of the E5A variant (t1/2 ~ 38 minutes) was not different from that of wild-type NM23-H1, however, suggesting lack of involvement of the 3′-5′ exonuclease function. Direct quantification of UVC-induced (6-4) photoproducts by immuno-slot blot analysis again revealed the 3′-5′ exonuclease-deficient mutant, E5A was fully active in DNA repair (Supplemental Figure 5A) whereas the kinase-deficient mutants, K12Q (Supplemental Figure 5B), P96S (Supplemental Figure 5C) and H118F (Supplemental Figure 5D) exhibited delayed repair relative to wild-type NM23-H1 during the early time points of the DNA repair response. NM23 expression did not regulate expression of a spectrum of NER-relevant proteins in the WM793-derived lines (Supplemental Fig. 6). Taken together, these results indicate the kinase activity of NM23-H1, but not the 3′-5′ exonuclease, contributes significantly to NER-mediated removal of UVR-induced (6-4) photoproducts, and strongly suggest the effect is not mediated indirectly by regulating expression of participants in the NER response.

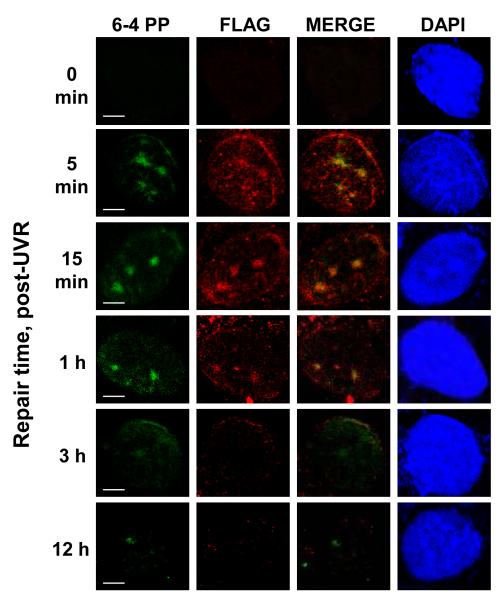

UVR-induced nuclear translocation and recruitment of NM23-H1 to local sites of (6-4) photoproducts

Immunolocalization studies were conducted to verify that NM23-H1 was recruited directly to (6-4) photoproduct lesions, coincident with its enhancement of (6-4) photoproduct removal (Fig. 3). To induce highly localized production of (6-4) photoproducts, UVC-irradiation was applied to 793H1-FL8 cells through UV-blocking Millipore filters containing 5 μm pores. After removing soluble NM23-H1 proteins by in situ detergent extraction, sequential application of anti-FLAG and anti-(6-4) photoproduct antibodies revealed rapid colocalization of NM23-H1 with sites of nuclear (6-4) photoproduct enrichment. Colocalization of FLAG-H1 and (6-4) photoproducts was apparent at 5 min of the UVC treatment, reached a maximum at 1h, and was dissipated by 12h. This time course closely paralleled that of NM23-H1-assisted disappearance of (6-4) photoproducts in the immuno-slot blot assay. These results demonstrate that NM23-H1 is rapidly recruited to sites of UVR-induced DNA damage and strongly suggests its direct participation in the early DNA damage repair response.

Figure 3.

UVR-induced nuclear translocation and recruitment of NM23-H1 to localized sites of UVR-induced DNA damage. 793H1-FL8 melanoma cells were UVC-irradiated through a polycarbonate UV-absorbing filter containing 5 μm pores (50 J/m2) and either processed immediately or allowed to repair for the indicated periods. Cells were subjected to an in situ detergent extraction protocol to remove soluble nuclear proteins, as described in Materials and Methods. A double immunofluorescence procedure was carried out to examine the co-distribution of FLAG-tagged NM23-H1 (red) and (6-4) photoproducts (green). Bars represent 5 μm.

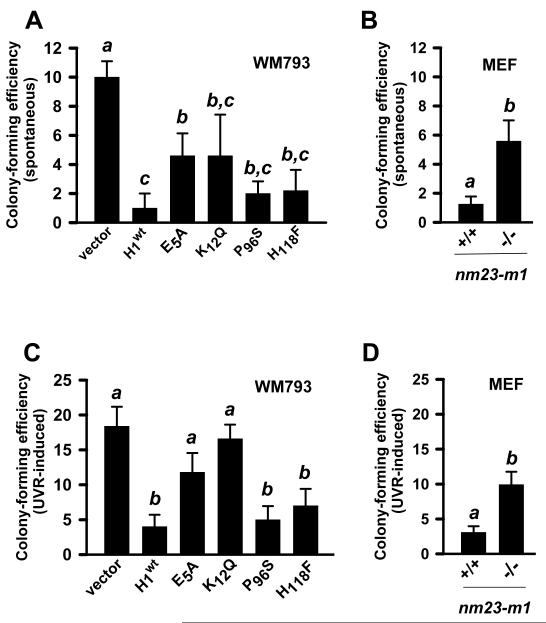

NM23-H1 suppresses spontaneous and UVB/A-induced mutations

Having demonstrated both the necessity of NM23-H1 expression for prompt repair of UVR-induced lesions and its rapid recruitment to sites of DNA damage, studies were next conducted to determine the extent to which the NM23 protein suppresses mutagenesis. Rates of spontaneous and UVR-induced mutagenesis within the hprt locus were quantified for the WM793 cell line panel and MEFs harboring a homozygous deletion of the nm23-m1 locus, using the 6-thioguanine-resistance (6-TGr) colony formation assay (27, 31). In the absence of UVR exposure, colony formation was reduced 10-fold by forced NM23-H1 expression (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4A). The 3′-5′ exonuclease-deficient mutants E5A and K12Q were also less effective than the wild-type protein in suppressing hprt mutations, with a 5-fold elevation in colony formation (P ≤ 0.05), while P96S and H118F did not differ from wild-type. In a similar fashion, MEFs expressing nm23-m1 had a reduction colony formation compared to lines harboring an nm23-m1 deletion (3.5-fold; P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Exposure to UVB/A resulted in increased colony formation in all cell lines relative to that seen in basal conditions. Forced NM23-H1 expression suppressed the UVR-induced increase in colony formation compared to the vector-transfected control (4-fold; P≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4C). E5A and K12Q both exhibited reduced suppressor activity, with colony formation not significantly differing from NM23-deficient control cells. In contrast, colony formation in cells expressing P96S and H118F equaled that seen with wild-type NM23-H1. As predicted, higher efficiencies of colony formation were seen in MEFs harboring an nm23-m1 deletion (4-fold; P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4D). These data indicate NM23-H1 deficiency confers increased mutagenic potential under basal conditions and following UVR exposure and indicate the 3′-5′ exonuclease activity of NM23-H1 is the predominant function required to suppress UVB/A-generated mutations.

Figure 4.

The 3′-5′ exonuclease activity and NDPK activities of NM23-H1 are necessary for preventing both spontaneous and UVB/A-induced mutations. Cell lines were either mock-treated or exposed to UVB/A (5 J/m2), with colony forming efficiency determined at 28 d post-6-TG treatment as described in Materials and Methods. A, spontaneous mutations in NM23-H1 deficient-human melanoma-derived cell line (WM793) and a panel over-expressing either wild-type NM23-H1 or enzymatic mutant variants (E5A, K12Q, P96S and, H118F) and B, MEFs from the parent C57/BL6 or m1−/− strains. C, UVR-induced mutations in NM23-H1 deficient-human melanoma-derived cell line (WM793) and a panel over-expressing either wild-type NM23-H1 or enzymatic mutant variants (E5A, K12Q, P96S and, H118F) and D, MEFs from the parent C57/BL6 or m1−/− strains. Values not sharing a common superscript are significantly different as determined by Fisher’s exact test (P < 0.05; n=5).

To obtain mutational spectra within the impacted hprt locus (Table 2), fifteen individual 6-TGR colonies were cloned from control- and NM23-H1-derived cell lines (spontaneous and UV-induced), followed by extraction of chromosomal DNA and sequencing between nucleotide positions 296-1051 (exons 2-9). Forced expression of NM23-H1 resulted in a 46 % reduction in total spontaneous mutations, and a 55 % reduction in UVR-induced mutations. Single base substitutions predominated in both cell lines, with higher rates of spontaneous and UVR-induced transitions and transversions in colonies derived from the vector-transfected control. Interestingly, C>T and T>C substitutions characteristic of UVR-induced damage occurred at higher frequencies in those clones.

Table 2.

Mutation spectra of spontaneously- and UVR- induced 6-TGr clones

| Spontaneous |

UVR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class of mutation‡ | Vector | + H1 | Vector | + H1 |

| Base substitutions | ||||

| Single | 32.5 ± 11 | 12.9 ± 7 | 55.1 ± 12 | 18.2 ± 8 |

| Transitions | ||||

| C>T | 3.2 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 23 ± 6.3 | 9.2 ± 0.6 |

| A>T | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.3 |

| G>C | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 0.4 |

| T>C | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 9.9 ± 1 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

| Transversions | ||||

| T>G | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| C>A | 3.9 ± 1 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| G>A | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| Tandem | ||||

| CC>TT | 4.2 ± 2 | 3.3 ± 5 | 9.6 ± 2 | 8.3 ± 0.3 |

| Frameshifts | ||||

| (1-2bp) | 10.4 ± 4 | 8.5 ± 6 | 3.2 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.5 |

| Others | 3.9 ± 4 | 3.0 ± 5 | 17.1 ± 3 | 12.1 ± 6 |

| Total | 51 ± 5 | 27.7 ± 5 | 85 ± 6 | 39.5 ± 7 |

Average number of mutations to occur per clone between positions 296-1051 bp of the hprt gene (n=15 per group).

NM23-H1 inhibits progression of WM793 melanoma cells to growth factor-independence

WM793 is a relatively invasive cell line derived from a VGP melanoma, but exhibits little metastatic potential when explanted in immunocompromised mice (17). Serial passaging in growth factor-free culture medium, however, eventually gives rise to colonies capable of autonomous proliferation (32), a well-recognized phenotype of metastatic cells. As this process requires multiple mitotic events and is likely to be driven by genomic instability, it was adapted as a novel assay for malignant progression.

All lines displayed similar growth rates during the adaptation cycle (data not shown) and after the first growth period in protein-free medium (Supplemental Fig. 7A; passage 1). After a total of 18 weeks of selection, colony formation and growth were accelerated significantly in parent WM793 cells, consistent with progression to growth factor-independent survival and proliferation. Forced expression of NM23-H1 significantly retarded colony development, strongly suggesting suppression of mutations required for growth factor-independence. The mutant K12Q deficient in both 3′-5 exonuclease and NDPK activity failed to suppress colony development (Supplemental Fig. 7A; passage 2), while the E5A, P96S and H118F mutants displayed intermediate phenotypes (Supplemental Fig. 7B; passage 2). Immunoblot analyses verified persistent forced NM23-H1 expression in the selected cell lines, with the exception of the wild-type protein which reverted to reduced levels, suggesting negative selection against it (Supplemental Fig. 7C). Failures of the 3′-5′ exonuclease- and NDPK-deficient mutants to resist progression to growth factor-independence are consistent with antimutator functions of these enzymatic activities of NM23-H1. Colonies obtained prior to growth factor-independence, had elevated levels of endogenously-generated 8-OHdG were observed in NM23-H1 deficient cells and the K12Q variant which lacks both the 3′-5′ exonuclease and kinase functions. After acquisition of growth factor-independence, all mutant variants of NM23-H1 (E5A, K12Q, P96S, and H118F) demonstrated elevated 8-OHdG content relative to the NM23-H1-expressing cells (Supplemental Fig. 8A and B). No evidence of NM23-H1-dependent alterations in gross chromosomal structure (Supplemental Fig. 9A-D) or microsatellite instability (Supplemental Fig. 10A-D) was obtained. Overall, these data further support an essential role for the 3′-5′ exonuclease and kinase functions of NM23-H1 in reducing accumulation of DNA damage contributing to malignant progression.

NM23 deficiency sensitizes mice to UVB/A-induced melanomagenesis

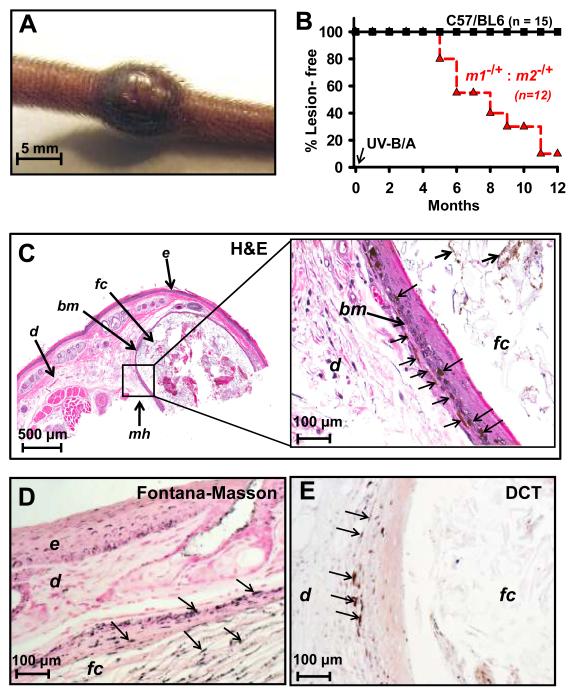

Our cell culture-based studies indicated NM23 proteins contribute to repair of UVR-induced DNA damage and suppression of both spontaneous and UVR-induced mutations. To determine the extent to which NM23 deficiency in vivo could confer increased susceptibility to UVR-induced DNA damage and tumorigenesis, the mouse strain harboring a tandem, hemizygotic deletion of the nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 loci (m1−/+: m2−/+) was subjected to an erythematous exposure to UVB/A irradiation at postnatal day 5. The homozygous-null condition is lethal in late embryonic and early neonatal development and could not be analyzed. UVB/A-irradiation resulted in appearance of melanocytic papules on the tails of almost all (11/12) m1−/+: m2−/+ mice (Fig. 5A). Tumors appeared at a median age of approximately 5 months-of-age (Fig. 5B), reaching maximum sizes of 10-90 mm3 (1-3 per mouse) by the 12 month termination point of the study. No lesions or hyperpigmentation were observed over the 12 month study in non-irradiated mice of the parental C57/BL6 or m1−/+: m2−/+ strain, nor in 15 C57/BL6 mice irradiated with UVB/A (data not shown).

Figure 5.

NM23 expression suppresses UVB/A-induced melanomagenesis in vivo. The parental C57/BL6 and hemizygous-null m1−/+: m2−/+ mouse strains (15 and 12 mice per strain, respectively) were exposed to a single neonatal erythemal dose of UVB/A (4000 J/m2) at postnatal age day four, as described in Materials and Methods. A, representative gross view of a raised pigmented tail lesion in a m1−/+: m2−/+ mouse at 12 months following UVR exposure. B, Incidence and time-course of UVR-induced tail lesions in C57/BL6 and m1−/+: m2−/+ mice. C, representative H&E section from an m1−/+: m2−/+ mouse containing a grossly identified tail tumor. At right is a higher magnification of the boxed area. Evident is a follicular infundibular inclusion cyst (fc) with proliferation of melanocytes (mh, melanocytic hyperplasia; thin arrows) along its wall and in the keratinous content (thick arrows). bm, basement membrane; d, dermis; e, epidermis. D, confirmation of melanin pigment within the keratin flakes (thin arrows) was obtained by positive Fontana-Masson (FM) staining. E, melanocyte identity (arrows) was confirmed by staining of dopachrome tautomerase (DCT).

To characterize UVR-induced melanotic tumors obtained in m1−/+: m2−/+ mice, histological examination was conducted on each of the eleven tail tumors, as well as two lesion-free tail samples from the parental C57/BL6 strain. In m1−/+: m2−/+ tumors, formation of follicular infundibular cysts (epidermoid type) was observed, with marked proliferation of dendritic and heavily pigmented melanocytes along the basement membrane of the cyst, consistent with in situ melanoma (Fig. 5C). Local invasion of these melanocytes was seen in adjacent dermis (Fig. 5C). High melanogenic activity of the melanocytes is illustrated by transfer of melanin to keratinocytes within the cyst wall and keratin flakes within the cyst interior, as confirmed by Fontana-Masson staining (Fig. 5D) and negative iron staining for hemosiderin (not shown). Melanocyte identity was confirmed by staining with antibody (PEP8) directed to dopachrome tautomerase (DCT; Fig. 5E). Mole-like lesions were also obtained in m1−/+: m2−/+ mice which exhibited accumulation of melanized dendritic melanocytes within the dermis, a feature not seen in tails of parental C57/BL6 mice. Of note is the similarity in morphological and cytological features of these tumors with UVR-induced melanomas obtained in a well-characterized mouse strain engineered for overexpression of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (33). In that strain, melanomas are characterized by heavily pigmented epithelioid and dendritic melanocytes of follicular origin, which is typical of spontaneous and induced melanomas in rodents.

DISCUSSION

These studies demonstrate a previously unrecognized role for the human NM23-H1 and mouse NM23-M1 isoforms in promoting the early repair response to UVR-initiated DNA damage, as well as suppression of UVR-initiated skin tumorigenesis. Such a function was initially suggested by demonstrations of antimutator activity for NM23 homologues in bacteria (34, 35) and yeast (16), as well as DNA cleaving activities in vitro for recombinant NM23-H2 (13) and NM23-H1 (14). The current study appears to explicitly define for the first time a DNA repair function for NM23-H1 (and probably NM23-H2) in the human and mouse, and specifically as a promoter of the NER pathway for repair of UVR-induced (6-4) photoproducts.

Analysis of catalytically-defective mutants of NM23-H1 revealed contributions of its kinase and 3′-5′ exonuclease functions in the early response to UVR-induced DNA damage against polymerase-blocking lesions and (6-4) photoproducts. While three variants used in this study (K12Q, P96S and H118F) exhibit moderate-to-severe deficiencies in NDPK and hisK activities, none are selective in their targeting of the two kinases (17). The NDPK activity seems a likely participant in light of its prior implication in antimutator functions in E. coli (35). All of the kinase- and/or 3′-5′ exonuclease-inactivating mutations were inhibitory to repair of overall UVR-induced DNA polymerase-blocking lesions in the hprt locus, strongly suggesting involvement of both activities across a spectrum of DNA damage. Mutational analysis demonstrated that only the kinase-defective mutants exhibited a deficit in promoting NER removal of (6-4) photoproducts, while the 3′-5′ exonuclease-defective mutants were fully active.

The apparent lack of contribution from the 3′-5′ exonuclease to repair of (6-4) photoproducts was anticipated in light of currently accepted molecular mechanisms of NER, which do not invoke 3′-5′ exonuclease activity (36). However, the 3′-5′ exonuclease of NM23-H1 clearly promotes repair of total UVR-induced (i.e. DNA polymerase-blocking) lesions and suppresses spontaneous and UVR-induced mutations, suggesting this activity may contribute to pathways other than NER, such as base excision repair, double strand-break repair and translesion synthesis, in which 3′-5′ exonucleases have been implicated (37,38).

The rapid co-localization of NM23-H1 with (6-4) photoproduct lesions raises the possibility that enzymes involved in dNTP synthesis are functionally coupled with DNA repair components at sites of DNA damage (39-41). Indeed, recent studies have implicated deoxyribonucleotide metabolizing enzymes in the DNA repair response, such as ribonucleotide reductase, p53R2 and thymidine kinase (42-45). The possibility remains open that the NDPK activity may deliver nucleotides directly to the DNA machinery during DNA repair processes, as hypothesized by multiple investigators (39-41).

NM23 expression did not promote repair of CPDs, suggesting it contributes to the early/acute phase of the DNA damage response (e.g. (6-4) photoproduct repair) and not the longer-term response involved in CPD repair. The selective enhancement of only (6-4) photoproduct repair by NM23 isoforms is not surprising, as a number of studies have reported important differences in repair of (6-4) photoproducts and CPDs (46, 47).

The strong penetrance of UVR-induced melanomagenesis and cyst formation in mice deficient in nm23-m1 and nm23-m2 provides important in vivo validation of the DNA repair-promoting function of NM23 proteins. These phenotypes strongly suggest specific contributions to the NER pathway, as knockout lesions in such NER participants as XPC and XPA, results in a similar spectrum of UVR-induced skin tumors (48, 49). nm23-h1 remains the prototypical metastasis suppressor gene, with a substantial body of literature affirming its ability to suppress tumor cell motility, invasive potential and the overall metastatic process in the absence of short-term effects on cell proliferation or primary tumor-forming potential. Our findings also establish the NM23 genes and their cognate proteins as suppressors of UVR-induced initiation and progression of melanoma in mice.

Tumor suppressor activity of the nm23-m1 and/or nm23-m2 genes is robust, having been demonstrated in the hemizygous-null condition. This high penetrance may be due to participation of NM23-M1 in multiple pathways for repair of UVR-induced DNA damage and/or cooperativity with loss in NM23-M2 expression. The ability of NM23-H1/M1 expression alone to promote the initial phase of the DNA repair response and suppress mutagenesis strongly suggests deficiency of this isoform is a major factor in the UVR-induced melanoma phenotype. Additional contributions of the M2 isoform are also suggested by the additional deficit seen in repair of UVR-induced damage in MEFs derived from m1−/−: m2−/− mice (Fig. 1). In a previous study, nullizygosity in the nm23-m1 locus failed to render susceptibility to diethylnitrosamine-induced liver carcinogenesis, athough progression to metastasis was enhanced (50). This discordance with our current study may be related to differences in the genotoxic stressors used (UV vs. chemical), the organs targeted for mutagenesis (skin vs. liver), and/or the genetic background of the mouse strains employed (129Sv:C57/BL6 vs. C57/BL6).

Loss of NM23 expression may represent a “double-hit” in which melanoma cells are not only more motile and invasive, but also genetically unstable and prone to progression- and metastasis-driving mutations. In support of this model, low NM23-H1 expression in primary melanoma has been associated with poor outcome (6-8). The possibility is suggested that NM23-deficient metastases in melanoma and breast carcinoma may arise from an NM23-deficient and, thus, genetically unstable subpopulation within the primary tumor. Our findings also raise the question of whether NM23-deficiency in the mouse results in mutations characteristic of human melanoma progression (e.g. b-raf/ras, pten, akt, et al.), and if so, whether they arise by a stochastic or directed process. Mouse models of melanoma capable of progression to NM23-deficiency-dependent metastasis should provide insights into this important issue in cancer biology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Edith Postel for providing nm23-null mice and mouse embryo fibroblast cultures. We also thank Glenn Merlino, John D’Orazio, Cynthia Long, and Nathaniel Holcomb for their helpful advice over the course of these studies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Grant CA83237 (to D.M.K.).

References

- 1.Rinker-Schaeffer CW, O’Keefe JP, Welch DR, Theodorescu D. Metastasis suppressor proteins: discovery, molecular mechanisms, and clinical application. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3882–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steeg PS, Bevilacqua G, Pozzatti R, Liotta LA, Sobel ME. Altered expression of NM23, a gene associated with low tumor metastatic potential, during adenovirus 2 Ela inhibition of experimental metastasis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:6550–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leone A, Flatow U, VanHoutte K, Steeg PS. Transfection of human nm23-H1 into the human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cell line: effects on tumor metastatic potential, colonization and enzymatic activity. Oncogene. 1993;8:2325–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leone A, Flatow U, King CR, Sandeen MA, Margulies IM, Liotta LA, et al. Reduced tumor incidence, metastatic potential, and cytokine responsiveness of nm23-transfected melanoma cells. Cell. 1991;65:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90404-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari D, Lombardi M, Ricci R, Michiara M, Santini M, De Panfilis G. Dermatopathological indicators of poor melanoma prognosis are significantly inversely correlated with the expression of NM23 protein in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:705–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florenes VA, Aamdal S, Myklebost O, Maelandsmo GM, Bruland OS, Fodstad O. Levels of nm23 messenger RNA in metastatic malignant melanomas: inverse correlation to disease progression. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6088–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caligo MA, Grammatico P, Cipollini G, Varesco L, Del Porto G, Bevilacqua G. A low NM23.H1 gene expression identifying high malignancy human melanomas. Melanoma Res. 1994;4:179–84. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal RP, Robison B, Parks RE., Jr Nucleoside diphosphokinase from human erythrocytes. Methods Enzymol. 1978;51:376–86. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)51051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freije JM, Blay P, MacDonald NJ, Manrow RE, Steeg PS. Site-directed mutation of Nm23-H1. Mutations lacking motility suppressive capacity upon transfection are deficient in histidine-dependent protein phosphotransferase pathways in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5525–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steeg PS, Palmieri D, Ouatas T, Salerno M. Histidine kinases and histidine phosphorylated proteins in mammalian cell biology, signal transduction and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003;190:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postel EH. Cleavage of DNA by human NM23-H2/nucleoside diphosphate kinase involves formation of a covalent protein-DNA complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22821–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postel EH, Abramczyk BM, Levit MN, Kyin S. Catalysis of DNA cleavage and nucleoside triphosphate synthesis by NM23-H2/NDP kinase share an active site that implies a DNA repair function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA. 2000;97:14194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma D, McCorkle JR, Kaetzel DM. The metastasis suppressor NM23-H1 possesses 3′-5′ exonuclease activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18073–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shevelev IV, Hubscher U. The 3′ 5′ exonucleases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:364–76. doi: 10.1038/nrm804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M, Jarrett SG, Craven R, Kaetzel DM. YNK1, the yeast homolog of human metastasis suppressor NM23, is required for repair of UV radiation- and etoposide-induced DNA damage. Mutat Res. 2009;660:74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, McCorkle JR, Novak M, Yang M, Kaetzel DM. Metastasis suppressor function of NM23-H1 requires its 3′;-5′ exonuclease activity. Int J Cancer. 2010;128:40–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herlyn M, Thurin J, Balaban G, Bennicelli JL, Herlyn D, Elder DE, et al. Characteristics of cultured human melanocytes isolated from different stages of tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5670–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herlyn M, Balaban G, Bennicelli J, Guerry Dt, Halaban R, Herlyn D, et al. Primary melanoma cells of the vertical growth phase: similarities to metastatic cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;74:283–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnaud-Dabernat S, Bourbon PM, Dierich A, Le Meur M, Daniel JY. Knockout mice as model systems for studying nm23/NDP kinase gene functions. Application to the nm23-M1 gene. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:19–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1023561821551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postel EH, Wohlman I, Zou X, Juan T, Sun N, D’Agostin D, et al. Targeted deletion of Nm23/nucleoside diphosphate kinase A and B reveals their requirement for definitive erythropoiesis in the mouse embryo. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:775–87. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott TL, Wakamatsu K, Ito S, D’Orazio JA. Purification and growth of melanocortin 1 receptor (Mc1r)-defective primary murine melanocytes is dependent on stem cell factor (SFC) from keratinocyte-conditioned media. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2009;45:577–83. doi: 10.1007/s11626-009-9232-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala-Torres S, Chen Y, Svoboda T, Rosenblatt J, Van Houten B. Analysis of gene-specific DNA damage and repair using quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Methods. 2000;22:135–47. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford JM, Hanawalt PC. Expression of wild-type p53 is required for efficient global genomic nucleotide excision repair in UV-irradiated human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28073–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wulff BC, Schick JS, Thomas-Ahner JM, Kusewitt DF, Yarosh DB, Oberyszyn TM. Topical treatment with OGG1 enzyme affects UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:317–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mone MJ, Volker M, Nikaido O, Mullenders LH, van Zeeland AA, Verschure PJ, et al. Local UV-induced DNA damage in cell nuclei results in local transcription inhibition. EMBO reports. 2001;2:1013–7. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaab WE, Tindall KR. Mutation rate at the hprt locus in human cancer cell lines with specific mismatch repair-gene defects. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaab WE, Risinger JI, Umar A, Barrett JC, Kunkel TA, Tindall KR. Cellular resistance and hypermutability in mismatch repair-deficient human cancer cell lines following treatment with methyl methanesulfonate. Mutat Res. 1998;398:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:148–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanawalt PC, Ford JM, Lloyd DR. Functional characterization of global genomic DNA repair and its implications for cancer. Mutat Res. 2003;544:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossman TG, Goncharova EI, Nadas A. Modeling and measurement of the spontaneous mutation rate in mammalian cells. Mutat Res. 1995;328:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)00190-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kath R, Jambrosic JA, Holland L, Rodeck U, Herlyn M. Development of invasive and growth factor-independent cell variants from primary human melanomas. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noonan FP, Otsuka T, Bang S, Anver MR, Merlino G. Accelerated ultraviolet radiation-induced carcinogenesis in hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3738–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordman J, Wright A. The relationship between dNTP pool levels and mutagenesis in an Escherichia coli NDP kinase mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10197–202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802816105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Q, Zhang X, Almaula N, Mathews CK, Inouye M. The gene for nucleoside diphosphate kinase functions as a mutator gene in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:337–41. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shuck SC, Short EA, Turchi JJ. Eukaryotic nucleotide excision repair: from understanding mechanisms to influencing biology. Cell Res. 2008;18:64–72. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang ZM, Yang XQ, Wang D, Wang G, Yang ZZ, Qing Y, et al. Nm23-H1 Protein Binds to APE1 at AP Sites and Stimulates AP Endonuclease Activity Following Ionizing Radiation of the Human Lung Cancer A549 Cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9238-9. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon JH, Singh P, Lee DH, Qiu J, Cai S, O’Connor TR, et al. Characterization of the 3′ --< 5′ exonuclease activity found in human nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1 (NDK1) and several of its homologues. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15774–86. doi: 10.1021/bi0515974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murthy S, Reddy GP. Replitase: complete machinery for DNA synthesis. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:711–7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim J, Wheeler LJ, Shen R, Mathews CK. Protein-DNA interactions in the T4 dNTP synthetase complex dependent on gene 32 single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1502–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen R, Olcott MC, Kim J, Rajagopal I, Mathews CK. Escherichia coli nucleoside diphosphate kinase interactions with T4 phage proteins of deoxyribonucleotide synthesis and possible regulatory functions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32225–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura T, Takeda S, Sagiya Y, Gotoh M, Nakamura Y, Arakawa H. Impaired function of p53R2 in Rrm2b-null mice causes severe renal failure through attenuation of dNTP pools. Nature genetics. 2003;34:440–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunos CA, Colussi VC, Pink J, Radivoyevitch T, Oleinick NL. Radiosensitization of Human Cervical Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Ribonucleotide Reductase: Enhanced Radiation Response at Low-Dose Rates. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2011;80:1198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen YL, Eriksson S, Chang ZF. Regulation and functional contribution of thymidine kinase 1 in repair of DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27327–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niida H, Katsuno Y, Sengoku M, Shimada M, Yukawa M, Ikura M, et al. Essential role of Tip60-dependent recruitment of ribonucleotide reductase at DNA damage sites in DNA repair during G1 phase. Genes & development. 2010;24:333–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1863810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koberle B, Roginskaya V, Wood RD. XPA protein as a limiting factor for nucleotide excision repair and UV sensitivity in human cells. DNA repair. 2006;5:641–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emmert S, Kobayashi N, Khan SG, Kraemer KH. The xeroderma pigmentosum group C gene leads to selective repair of cyclobutane prrimidine dimers rather than 6-4 photoproducts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2151–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040559697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang G, Curley D, Bosenberg MW, Tsao H. Loss of xeroderma pigmentosum C (Xpc) enhances melanoma photocarcinogenesis in Ink4a-Arf-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5649–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Schanke A, van Venrooij GM, Jongsma MJ, Banus HA, Mullenders LH, van Kranen HJ, et al. Induction of nevi and skin tumors in Ink4a/Arf Xpa knockout mice by neonatal, intermittent, or chronic UVB exposures. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2608–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boissan M, Wendum D, Arnaud-Dabernat S, Munier A, Debray M, Lascu I, et al. Increased lung metastasis in transgenic NM23-Null/SV40 mice with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:836–45. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.