Abstract

Background:

Around 2 million people are living with or beyond cancer in the UK. However, experiences and needs following primary treatment are relatively neglected. Following treatment, survivors may feel particularly vulnerable and face threats to their identity. We present a conceptual framework to inform areas of self-management support to facilitate recovery of health and well-being following primary cancer treatment.

Methods:

To explain the framework, we draw on data from two studies: UK-wide consultation about cancer patients’ research priorities and survivors’ self-management in the year following primary cancer treatment.

Results:

Self-confidence may be low following treatment. Recovery includes rebuilding lost confidence. Support to manage the impact of cancer on everyday life was a priority. Self-management support included health professionals, peers, employers, family, friends and online resources. However, support was not always available and confidence to access support could be low.

Conclusion:

Cancer survivors may struggle to self-manage following primary treatment where confidence is low or support is lacking. Low confidence may be a significant barrier to accessing support. Supporting recovery of self-confidence is an important aspect of recovery alongside physical and psychosocial problems in the context of changing health care and cancer follow-up.

Keywords: self-management support, confidence, survivors, recovery

Around 2 million people are living with or beyond cancer in the UK and this figure is rising by more than 3% per year (Macmillan, 2008). More people are living for longer following a cancer diagnosis and many are living with long-term consequences (Foster et al, 2009). The emerging picture is of people living after a diagnosis of cancer, free from active disease, yet having similar health and well-being profiles to people living with a long-term condition (Maher and Fenlon, 2010) with high usage of health services (Hewitt et al, 2003; Nord et al, 2005). However, the experiences and needs of those who have completed primary cancer treatment are poorly understood and relatively neglected (DoH, 2007). Health professionals may be unaware of who is struggling with problems (Maher and Makin, 2007). How to best assess problems faced or which interventions are effective in helping relieve or prevent problems following primary treatment are largely unknown (Corner, 2008).

People generally manage problems associated with cancer and its treatment as part of their daily lives. Many want an active role in tackling them (Brennan, 2004; Hopkinson and Corner, 2006), but little is known about how people affected by cancer manage to live with persistent problems once primary treatment is complete, and how they can be supported to do this. With rising numbers of survivors, the need to understand problems faced following treatment, how they are resolved and how to support people to manage them are becoming increasingly important for cancer survivors, service planners and health policy makers. For example, the shifts in care and support for people living with and beyond cancer outlined by the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative include a shift towards support for self-management including self-directed follow-up (DoH, Macmillan and NHS Improvement, 2010). By drawing on data from our research and relevant literature, this paper presents a conceptual framework, directly shaped by the experiences and priorities of cancer patients and survivors, to inform how health professionals and others can support recovery and self-management by recognising the importance of self-confidence in the management of problems following primary treatment. This framework guided the design of our survivorship research programme including mapping the recovery of 1000 colorectal cancer patients and the co-creation of a resource designed to enhance self-confidence in self-managing a specific problem following primary cancer treatment (cancer related fatigue).

Life after primary cancer treatment

It has been recognised that people face particular challenges when primary cancer treatment comes to an end. Individuals may face a range of problems including fatigue, concerns about recurrence, dealing with others’ expectations that life should be ‘back to normal’, having to adjust expectations about physical ability and concerns about leaving the hospital system (Jefford et al, 2008), as well as concerns about the impact on family and friends and unmet supportive care needs (Armes et al, 2009). The time of transition from active treatment to follow-up has been associated with distress due to the loss of frequent medical monitoring and support, and the shift in responsibility to the individual, resulting in feelings of abandonment, vulnerability and the loss of a ‘safety net’ (Ward et al, 1992). At this time, cancer survivors may take stock and realise that life may never completely return to normal (Allen et al, 2009). Not only may they grieve the loss of the previous life, but they also need to adapt to fundamental changes that have taken place in their lives. Cancer is largely regarded and treated within an acute illness framework and the realisation for the individual that there are chronic changes associated with cancer, and its treatment may bring about new challenges. Charmaz (1983) discusses how expectations within this acute medical framework, and within Western societies, are that people should return to ‘normal life’ and that this in itself becomes the symbol of a valued self. Where people are unable to do this, or it takes longer than expected (Rasmussen and Elverdam, 2007), the loss of this former valued self becomes a source of suffering. This suffering takes the form of restricted lives, social isolation, being discredited and becoming a burden to others (Charmaz, 1983). Further consequences of chronic illness are a loss of productive function, financial crises and family strain.

Thus, the problems of cancer survivorship are broader than the physical consequences and psychological distress of cancer diagnosis and treatment, and, similar to people with other chronic illnesses, cancer survivors need to undertake work to rebuild and integrate their disrupted identities into new and changed identities (Bury, 1982). Many cancer patients are reported to become ‘lost’ in this transition from patient to survivor (Hewitt et al, 2005). Given current changes in provision of care for follow-up of cancer survivors, it is timely to address how this transition can best be supported.

Self-management and self-management support

Karnilowicz (2011) argues that chronic illness identity work is mediated through psychological ownership of illness, and that the experience of owning an illness is fixed in the idea of control. The greater the level of control the more likely control is experienced psychologically as part of self, and there is a close and ongoing interaction between an individual's psychological state and his or her social environment (Shaw, 1999). Regan-Smith et al (2006) suggest that self-care behaviours are integral in re-establishing ownership, and people with high levels of self-efficacy are more likely to engage in self-care behaviours. Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986; a component of Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory) refers to the confidence one has to achieve particular goals in living with or managing problems associated with illness. High self-efficacy is associated with a greater effort and persistence to cope with obstacles (Bandura, 1977) and enhanced well-being (Lev et al, 2001). Where there is a high degree of self-efficacy in people affected by cancer a number of improvements in health-care outcomes result, including increased self-care behaviours and decreased physical and psychological symptoms (Egbert and Parrott, 2001; Luszczynska et al, 2007). The terms self-care and self-management are often used interchangeably. Self-care is generally regarded as a broader term encompassing all actions that individuals take to care for themselves to maintain health and well-being, whereas self-management is more focussed on the ability to manage day-to-day problems that result from long-term and chronic health conditions (Coulter and Ellins, 2006).

Managing everyday problems brought about by cancer/treatment is likely to be enhanced by a collaborative partnership between patients and health-care providers, who are equally considered to be experts of the condition, albeit from different perspectives (Von Korff et al, 1997). A collaborative approach that delineates how the health-care system and health-care professionals can support patients in their self-management has been referred to as self-management support. The Health Foundation describes self-management support as those things that can be performed by health services to aid and encourage people living with long-term conditions to improve or maintain their own health and well-being (Fenlon and Foster, 2009). It can be viewed in two ways: as a portfolio of techniques and tools and as a fundamental transformation of the patient–caregiver relationship into a collaborative partnership. This has been described as follows:

A whole-system approach. It involves far more than providing a one-off expert patient course, although these can be useful. Clinical services, systems, processes and environments must all convey to patients the message: ‘You have a part to play. We are partners. We respect your role and will support you to be part of the team’. (Grazin, 2007).

Thus, the principle of supporting self-management through partnership working reverses the focus on telling patients what they ‘should do’ to one where the patient is supported in addressing their own agenda. We would argue that self-management support is broader than health services alone, and includes support from other sources such as other cancer survivors, workplace, community support, online resources and so on.

Self-management programmes, such as the Expert Patient Programme, established to provide people with a generic set of skills to self-manage successfully, have been shown to improve self-efficacy and health status (Kennedy et al, 2007). The central tenet of many such programmes is that patients can be educated to self-manage their condition (Lorig, 2002), and this will increase their self-efficacy to manage their own illness, improve quality of life and reduce health service utilisation. Such programmes have been criticised for drawing on sociological research into the everyday realities of living with chronic conditions and ‘transforming what patients do into what patients should do’ (Bury, 2010). Kralik et al (2004) have suggested that although ‘self-management’ is key to the identity work required by people with long-term conditions, they highlight that ‘self-management’ is conceptualised quite differently by health professionals and people with long-term health conditions. Health professionals identify self-management as structured education, but those with long-term health conditions identify self-management as a process initiated to bring about order in their lives (Kralik et al, 2004). Creating the conditions to enable people to self-manage this transition and restore order in their disrupted lives will be necessary rather than turning patient actions into directives for others to follow. Programmes for self-management may be part of a culture shift towards creating these conditions, but there needs to be a more fundamental shift in the way that health care is delivered.

Using empirical data collected from our research, we have brought together patients’ and survivors’ priorities and experiences with existing models of recovery of health (including physical, mental and social health), well-being and quality of life after cancer (Lent, 2007; Victorson et al, 2007), into a conceptual framework to identify where health professionals and others may be able to support cancer survivors’ self-management of problems and enhance recovery of health and well-being following primary cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

We draw on two research studies here to support the development and focus of our conceptual model of self-management and self-management support following primary cancer treatment: one involving cancer patients in a UK-wide consultation to identify priorities for research (Wright et al, 2006; Corner et al, 2007) and the other involving survivors in the year following primary cancer treatment to examine self-management of problems associated with cancer (Foster et al, 2010). Findings from these and related studies (e.g., Foster et al, 2007; Foster and Roffe, 2009) have provided the data to support the development of this conceptual model and to underpin a new research programme to better understand this stage of the cancer experience and inform the development of self-management support. Further details of the two studies described in this paper are available in the related publications and study reports.

Design

Macmillan listening study (MLS)

The purpose of the study was to reach consensus over patients’ priorities for cancer research (Corner et al, 2007). The study involved a UK-wide consultation with patients (on and off treatment), with early stage to advanced cancer, and included typically underrepresented parts of the population in cancer research (e.g., patients >75 years, minority ethnic patients). Nominal group technique was used to determine priorities for research in cancer generated by patients themselves.

After cancer treatment (ACT) study

This qualitative, exploratory study utilised a cross-sectional design. The aim was to gather accounts of strategies used to self-manage problems arising from cancer and its treatment and focused on the year following primary cancer treatment. Participants were interviewed, and included a diverse group of people following their treatment for non-metastatic cancer. Analysis of interview transcripts enabled description and interpretation of individuals’ experiences designed to build an understanding using a systematic set of strategies for organising, structuring and analysing complex qualitative material (Strauss and Corbin, 1990).

Participants

MLS

A total of 105 participants (⩾18 years) were recruited through outpatient clinics in seven cancer centres across the UK. Consultation groups were also run with purposively selected participants from frequently under-researched communities including minority ethnic groups, people over 75 years and those with advanced cancer.

ACT

A total of 30 men and women (⩾18 years of age) who were 6–12 months post treatment for primary cancer agreed to participate following advertisements in the local press. Efforts were made to include a broad spectrum of individuals, for example, with regard to cancer type, age, gender, treatment type (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy or combination treatment) and involvement in formal self-help activities. This was not intended to be a representative sample, rather a group of people with diverse experiences that could provide insights into self-management of problems following primary treatment.

Procedure

Ethics approval was gained through the South East Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (MLS) and School of Health Sciences, University of Southampton (ACT). All participants gave written consent.

MLS

Consultation groups were the main method of data collection, which combined a focus group approach with an adapted Nominal Group Technique to achieve consensus over research priorities.

ACT

Participants were recruited through the local media. Purposive sampling was used to include a range of cancer/treatment types, age and gender. Semistructured interviews included an invitation to describe key problems currently experienced (e.g., physical, psychosocial and practical) that had arisen since their diagnosis of cancer and associated with cancer/treatment; a request to focus, where possible, on the most significant change or problem and give accounts of problem experienced; strategies used to manage the problem themselves; how these strategies were chosen/discovered; whether strategies were perceived to be effective; the nature of support available/required to manage the problem themselves; and views of preferred self-management support. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were managed and retrieved using the NUD*IST 6 software (Victoria, Australia). Pseudonyms are used for all quotes.

MLS

The consultation groups generated two forms of data, which were analysed by the research team: a ranked list of research topics and questions arranged into themes within each consultation group by participants, and transcripts of recorded discussion. The transcripts provided contextual data regarding the meaning of research topics, as well as participants’ rationale for identifying them as important. To develop a composite list of research themes across all consultation groups, a process for grouping similar clusters of research topics was undertaken using a form of thematic analysis (Strauss, 1987). The ranked lists of research themes for the consultation groups were then combined taking into account the ranked scores of each theme within each group. The consultation group transcripts were also subjected to thematic analysis. This was appropriate given the need to contextualise the identified research priorities.

ACT

An inductive, discovery-oriented method was used to generate new hypotheses and uncover fresh perspectives. This approach enabled description and interpretation of individuals’ experiences designed to build understanding using a systematic set of strategies for organising, structuring and analysing complex qualitative material (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). All interview transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis and constant comparison to describe and explain the nature of strategies used, and the experience of using such strategies to manage self-selected problems. Central to this process is analysis through ‘open coding’, which allows categories to emerge from the data inductively through systematic inspection of the transcripts.

For the purposes of this paper, the findings are reported as one rather than by project.

Results

Participants

A total of 17 consultation groups were conducted with 105 participants, with a median of 6 (range 3–11) participants in each. Participants had a range of cancer types and sites, 68% were women and 11% of participants were from Black-Caribbean and South-Asian Groups (see Corner et al (2007) for further details).

A total of 30 cancer survivors participated in in-depth interviews. Among them, 24 (77.5%) were women. The majority (n=20) were aged 50–69 years. Participants had a wide range of cancer types (including rarer cancers) and sites, with breast cancer being the most common (n=15), followed by cancer of the colon (n=5) and ovarian cancer (n=3). Participants had received a range of treatments including chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery. Most were in receipt of regular follow-up (see Foster et al (2010) for further details).

Impact of cancer on everyday life

The analysis of the consultation groups identified that people affected by cancer saw the Impact of cancer on everyday life as a priority for research (Corner et al, 2007), such as support with living with cancer and its consequences at home. The issue of ‘Impact on everyday life’ was very broad, encompassing nine areas including psychological consequences, self-help groups and peer support, follow-up and after care, impact on social functioning, work and other financial impacts, managing pain, impact on family and others, diet in managing cancer and general lifestyle issues in managing cancer (Okamoto et al, 2011). Participants viewed these as different aspects of the problems and issues of living with cancer on a day-to-day basis.

For many participants, cancer had a significant impact on their day-to-day activities. Research into the impact of cancer on social functioning and how these can be supported was important to many participants. Participants justified reasons for this being a priority area by sharing experiences of how cancer had impacted on their lives, preventing them from sleeping, travelling, driving, shopping, taking part in recreational activities and so on.

There's also travel, that was a big part of my life, travelling… … So, I feel very much cut off, I can’t work, I can’t drive, I can’t travel. Life has had to take a completely different turn and it's very hard to keep cheerful. (Brian) Yes, I’d go along with that, exactly, you are limited, your driving, isolates you, shopping, everything and you’re dependent on other people. (Tim)

Related to this lack of independence was concern at the way people's treatment of the cancer patient changed. Participants spoke of ‘losing power’, of not ‘being in control’, of being made to feel ‘abnormal’, as if they ‘didn’t exist’.

The recovery process: adjusting to a changed self

Participants described the long process of recovery as important work in the year following the completion of their primary cancer treatment. This included recovery from physical symptoms, as well as psychological recovery, the unanticipated amount of time problems persisted for and the desire to be the person ‘I used to be’.

I didn’t want to be there, I wanted to be how I used to be and I have trouble with that, trying to adjust. (Ruth)

Having come through often gruelling treatment, which had taken its toll physically and psychologically, it was challenging to deal with new experiences and problems arising from cancer and its treatment, and raised particular challenges for some in terms of psychological adjustment.

I can remember having an accident in the car and my pride was hurt, you know, bash your car, drive into the back of people sort of thing, and that pride is hurt, and being ill is a similar sort of experience, you’ve had something happen to you and it's happened, and you don’t know how to deal with it, ‘cause it's never happened before. But to be really ill and not be able to deal with it makes you worse… (Howard)

Cancer and its treatment had a profound impact on all aspects of life, and these took time to recover from expectations that ‘you should feel better’ and ‘get on with life’ following treatment, which were unhelpful.

…and the fact that you think you should feel better makes you feel worse because you think everybody is thinking ‘Right that's your treatment now get on with life’ but physically you sort of feel down so I was feeling like I could do things one day and feel exhausted the next day. (Joanne)

Vulnerability and loss of confidence: rebuilding confidence during recovery

Some problems did not resolve but were ‘lived with’ by a number of adjustments to everyday living, and problems associated with cancer and consequences of treatment could have a profound impact on confidence to manage cancer/treatment-related problems (self-efficacy) with a knock-on impact on important areas of life such as relationships and work.

OK I am 40 now and I’ve come to terms with it all but it is still quite tough to do that knowing it is never going to get any better than that so that was difficult. And it has, not really on a sexual side, but it has contributed to my complete loss of confidence and I lost my job really because I just couldn’t cope. (John)

During this period of recovery from cancer and treatment, a general sense of having one's confidence knocked down was described by a number of participants and this lack of confidence made it difficult to ask for help. Regaining previous confidence was an important part of recovery and could be facilitated by personal attributes and others such as family, partners, friends, colleagues and employers – such as through a gradual return to work following a long absence for treatment.

But it was all very internal with me. I hadn’t gone out and asked for help and that was part of my stress. I hadn’t stood up and said ‘bloody hell, take notice of me’ and that is what caused my stress really because I hadn’t had the confidence to go and do that really. But I said I have got a fantastic partner who has helped me through it and a fantastic family, they care and they worry too much but they are brilliant. (John)

Lack of confidence and vulnerability could limit the amount of support individuals received in their recovery following primary treatment, including times when support was available but was not accessed.

I think you feel a little bit that you are being a nuisance. I mean I had the support from family and that was OK, but I still think – I mean I would have felt terrible ringing somebody and saying. I just couldn’t have done it. [….] But then you see if they see you coming in and you are coping and they think you are all right, they don’t tend to – if you put a cover on it and you are not showing that you’re worried and then I don’t suppose they think about it quite so much do they? But if you went in there really depressed and full of gloom and doom, then they would think ‘oh well perhaps she needs a bit of counselling or whatever’ then they would offer it you. [….] [INT: So you weren’t really sure who you could contact?] No I wasn’t no. No. Because I didn’t know. And that's a part my own fault, ‘cause I should have asked, but then I think at the time you don’t. You feel very vulnerable to have to ask for help, I think that's what it is, it's being able to ask for their help isn’t it? (Charlotte)

Self-management and self-management support

Following primary treatment, many survivors found ways to self-manage problems they were experiencing. This involved personal resources such as being proactive in seeking out information and support, managing symptoms, thoughts and expectations, carefully planning activities, and making connections with others with similar experiences, as well as self-efficacy (confidence) to do these things. Examples include maintaining a positive outlook on life, organising activities to allow for physical challenges such as fatigue or mobility problems following primary treatment (Foster et al, 2010).

Sources of self-management support were varied and involved drawing on support from family, friends, health-care professionals, colleagues, the Internet and so on. Email and the Internet can be a valuable means for supporting self-management by providing information and enabling people to seek and share advice with others they might not otherwise come into contact with (Foster and Roffe, 2009). However, the right support may not be forthcoming or is hard to find.

I felt that I was a bit left in the lurch afterwards, that's how I felt about it. That I didn’t have enough backup then – the sort of ‘is it going to come back?’ And all them sort of things, and then just getting back to work. Was I going back to work? Was I not? Was I feeling well enough? And I just think I could have done with a little bit more of a professional body more than just your family and friends really. … You don’t want to upset people around you so much, you still hide a lot of it, because I think if you had somebody else to talk to at that time, you would have opened up a lot more and maybe it would have been a lot easier, I don’t know. But that's how I feel about it myself really. (Charlotte)

Although many people are resourceful in drawing on their own personal strengths and resources and in drawing on support from others, this can be hard for those lacking in confidence or less able to do so. How people manage this at a time when they are vulnerable and recovering from cancer and its treatment were varied but the importance of personal resources such as confidence and assertiveness is clear.

Although some people were proactive at reaching support, this was not always adequate. Some who described themselves as reasonably confident described their encounters with health-care professionals as leaving them feeling ‘a bit thick’ or ‘embarrassed’ and ‘wasting their time’.

The breast nurse was the first port of call because they were the people that said ‘If there's anything’ but I just, a few times that I’ve been down there I just get to the stage of feeling embarrassed, which is not like me and I feel that I’m wasting their time. (Judy)

Others felt that having health-care professionals make contact with people once their treatment was over to see how they were doing would have been preferable – especially for those who did not feel they could ask for help. Consultation group participants wanted more research to go into follow-up and aftercare. In particular, they wanted researchers to explore the extent to which follow-up services meet the needs of people affected by cancer. This was important to participants, as there was a general sense that aftercare services could be improved:

‘It just seems to be, ‘Right, you’ve had your operation, you’re fine… cheerio now, we’ll see you in six months time’, and you’re out the door and that's it, get on with your life again.’ (Alan)

In summary, participants described complex elements of recovery, including adjusting to a changed self, expectations that things ‘ought’ to be better and finding it hard to deal with this psychologically. This may be accompanied by feelings of vulnerability and a lack of self-confidence. In this context, support to manage problems associated with cancer and treatment that affects everyday life is needed to help rebuild confidence. Participants reported various ways in which they attempted to self-manage a wide range of cancer-related problems, and gave accounts of how they drew on the support of others, as well as their own personal resources. In doing so, this helped them to manage, although not necessarily resolve, the problems they were facing. Where individuals struggled to obtain support from others – family, friends, health-care professionals and so on – this hindered their self-management of problems. Similarly, where individuals did not feel confident to manage, they reported struggling to self-manage. Although our research demonstrates that people can successfully self-manage problems following cancer treatment, there is a need for a supportive infrastructure for survivors of cancer that takes into consideration low confidence as a significant barrier to support. Some struggle to self-manage problems without the necessary confidence, appropriate information, health care and support (Foster et al, 2010).

Developing a conceptual framework – recovery of health and well-being in cancer survivorship

Key messages from our research are that many people want more help in a variety of forms to manage the impact of cancer on their lives, but that the cancer diagnosis and treatment leaves them vulnerable and lacking in confidence. We know from chronic illness research (e.g., Bury, 1982; Charmaz, 1983) that many cancer survivors are likely to need to rebuild their lives and identity, but diminished confidence may leave them ill-equipped to do this. We suggest that rebuilding confidence is an important part of recovery, and if patients can be supported as they rebuild their confidence following primary cancer treatment they will be in a better position to self-manage problems and access self-management support as required. This in turn will influence recovery of health and well-being following cancer treatment and ultimately whether individuals ‘live well’ after treatment. The fundamental principle informing the conceptual framework is that confidence to manage problems arising from cancer and its treatment is key and some people want and need support to help them become more confident to self-manage problems that impact on everyday life (Corner et al, 2007; Foster et al, 2010).

It has long been recognised that there is considerable variation in how people respond to objectively similar stressful life events, such as a diagnosis and treatment for cancer (Bandura, 1977; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Model of restorative emotional well-being for cancer survivors by Lent (2007) suggests that two key facets for restoration of emotional well-being are the individual's characteristics and the environmental supports and resources available to them. Drawing on Bandura's (1986) concept of self-efficacy, Lent (2007) suggests that the ability of the individual to cope with their perceived problems depends on personality and affective dispositions, and that people's emotional well-being will depend on their dispositions, as well as their environmental supports and resources. The model recognises that through their different dispositions, supports, resources and coping efficacy, people will differ in the restoration of health and well-being, their self-management activity and their need for self-management support.

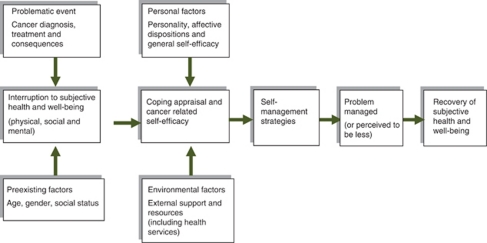

Our conceptual framework focuses on recovery of health and well-being following primary cancer treatment (vs emotional well-being). We have brought together our data with Lent (2007) model of restorative emotional well-being and expanded the model to incorporate wider domains that may impact on recovery of health and well-being.

Although our framework (Figure 1) brings in the wider domains of health and well-being, our research to date suggests that self-confidence is key to enabling people to manage problems following primary cancer treatment and that this is important for recovery of health and well-being. The model illustrates how the problematic event (e.g., cancer diagnosis or perception of problem following primary treatment) and preexisting factors such as the person's age, gender and social status will influence how disruptive cancer and its treatment are to the person reflected in their subjective health and well-being. There is a process of appraising the situation (coping appraisal) and appraisal of cancer-related self-efficacy (confidence) to manage the situation. How the person appraises the situation and whether or not they feel equipped to deal with it are in turn influenced by personal factors such as personality and general self-efficacy and environmental factors (such as health and social care, family and friends, workplace and community support). For example, if people are lacking in confidence to manage cancer-related fatigue associated with cancer/treatment, this may be improved by altering how the person interprets their fatigue or through support from peers. Coping and self-efficacy appraisals to manage cancer-related problems in everyday life will influence the type of self-management strategies used. The type of self-management strategies used will influence whether the problem is managed (e.g., improvement in the perception of problem, such as whether it is less bothersome, rather than necessarily removing the problem) and ultimately influence perceived health and well-being. It may not be possible for problems to be eradicated, but they will be perceived to be less of a problem if the person feels confident to self-manages them in their everyday life. The model recognises that people have different dispositions, supports and resources, individual differences in self-efficacy, need for self-management support and self-management activities undertaken influencing problem resolution and recovery of health and well-being.

Figure 1.

Recovery of health and well-being in cancer survivorship (adapted from Lent, 2007; Foster et al, 2010).

Grounded in our research data and the literature, the conceptual framework has two assumptions. One is that cancer diagnosis and treatment disrupt an individual's subjective sense of health and well-being, and the second is that this is restored over a period of time (although not necessarily to the same/similar level as prediagnosis). The linear nature of the model reflects the passage of time. However, for many people restoration of health and well-being is likely to be accompanied by a life free from cancer, whereas others may experience long-lasting problems as a consequence of cancer and its treatment or may face cancer recurrence. The phase of problem resolution and restoration of health and well-being may therefore be protracted or repeated. Our programme of research is designed to map how long it takes for people to recover a sense of health and well-being and what influences this. We hypothesise that it will be possible to predict who is at risk of poor recovery of health and well-being, and that specific support designed to help cancer survivors feel more confident to manage cancer-related problems, where appropriate, may facilitate a more rapid recovery of health and well-being following primary cancer treatment.

There are a number of limitations affecting our research to date, which we intend to address in our next phase of research. We have recruited more women than men into the studies we report here and intend to address this in a cohort of colorectal cancer survivors. In addition, we have included a broad spectrum of cancer patients in our studies, including those who have completed primary treatment and are disease free, as well as those with advanced cancer. This gives us a broad insight into life after primary cancer treatment for those included in the definition of survivorship: those living with and beyond cancer. Our cohort study will focus on colorectal cancer patients (diagnosed with non-metastatic disease) from the point of primary surgery. We recruited through the local media for the ACT study to include people who may not have accessed cancer follow-up services in the year following primary treatment. Although this may be viewed as a potential weakness, we found a range of experiences including those who were living well following their treatment. In our cohort study, we will recruit participants through a large number of cancer centres across the UK. In this paper, we have focused on problems faced by some cancer survivors following their primary treatment to illustrate our conceptual framework. This is not to say that all people will experience problems following their primary cancer treatment, nor will all people want support to manage problems in their everyday life once treatment is over; however, for those who are experiencing problems, there is a need to examine what might help enhance their recovery from cancer and its treatment.

One key element of our research programme is a UK-wide cohort of 1000 colorectal cancer survivors. The purpose of this cohort is to map the path of recovery over the years following primary surgery using time points selected through clinical considerations, and mapping recovery at each time point by assessing variables informed by the conceptual model. These include details about cancer/treatment, demographic details, health and well-being, coping appraisal and self-efficacy, personality, affective disposition, social support, health-service use and self-management strategies used. We will identify who is most at risk of problems, what environmental supports and resources people find helpful and what support needs to be in place to enhance people's self-efficacy, lead to problem resolution and restoration of health and well-being.

We have focused on colorectal cancer survivors as they are the largest group of survivors of a cancer that affects both men and women (National Cancer Intelligence Network, 2010), and there is little longitudinal work on the pattern of recovery of health and well-being in colorectal cancer patients on which to base the development and testing of supportive interventions or where to target clinical services. Findings from the cohort will inform the development and testing of self-management support for cancer survivors.

We are also developing an online self-management resource to support patients in their recovery following cancer treatment. This online resource will bring together clinical and lay expertise to support recovery from cancer treatment. In this way, recovery can be ‘co-created’ where both clinical and lay experience and knowledge can contribute to self-management of everyday problems resulting from cancer and its treatment. In addition, a number of structured activities designed to enhance self-efficacy and self-management will form part of the online resource.

Conclusion

Cancer survivors face a number of challenges following primary treatment at a time when they may feel particularly vulnerable and have low self-confidence. However, many people use a range of strategies to self-manage problems following primary treatment. Personal and environmental resources have a part in how problems are managed in everyday life once primary treatment is over, which in turn can influence recovery of health and well-being. Our framework recognises that restoration of self-confidence and confidence to self-manage cancer-related problems are central to people's recovery of health and well-being in cancer survivorship. Health-care providers can influence how confident people feel to self-manage, and this may be achieved in a number of ways.

Failing to provide appropriate long-term support across the spectrum of problems faced following primary treatment may have negative consequences for health and well-being of the growing number of survivors (Maher and Makin, 2007) and may prevent them from returning to productive lives, both socially and economically (Corner, 2008). Evidence suggests that most survivors manage to live well with problems associated with cancer and its treatment; however, a substantial minority (around one-third) consistently report difficulties in the long term (Foster et al, 2009). Early intervention could help alleviate some longer-term problems and reduce burden on health services (van de Poll-Franse et al, 2006). To know how to intervene, we must first understand how health and well-being is restored over time (or not), what factors indicate who is most likely to need support and when and what forms self-management support should take.

Acknowledgments

We thank the co-researchers, research partners and participants in the studies; Macmillan Cancer Support for funding this research and our Macmillan Survivorship Research Group programme; members of the Macmillan Survivorship Research Group team for their contributions to the studies; and colleagues in Faculty of Health Sciences for reviewing the earlier versions of the paper. This article is sponsored by Macmillan Cancer Support.

References

- Allen JD, Savadatti S, Levy AG (2009) The transition from breast cancer ‘patient’ to ‘survivor’. Psychooncology 18(1): 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morhan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, Palmer N, Ream E, Young A, Richardson A (2009) Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 27(36): 6172–6179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977) Social Learning Theory. General Learning Press: New York [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J (2004) Cancer in Context: A Practical Guide to Supportive Care. Oxford University Press: Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Bury M (1982) Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn 4(2): 167–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M (2010) Chronic illness, self-management and the rhetoric of empowerment. In New Directions in The Sociology of Chronic and Disabling Conditions: Assaults on the Lifeworld, Scambler G, Scambler S (eds), Chapter 8. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (1983) Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 5(2): 168–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corner J (2008) Addressing the needs of cancer survivors: issues and challenges. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 8(5): 443–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corner J, Wright D, Hopkinson J, Gunaratnam Y, McDonald JW, Foster C (2007) The research priorities of patients attending UK cancer treatment centres: findings from a modified nominal group study. Br J Cancer 96(6): 875–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A, Ellins J (2006) Patient-Focused Interventions: A Review of the Evidence. Picker Institute Europe, The Health Foundation: London [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (DoH) (2007) Cancer Reform Strategy. HMSO: London [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (DoH), Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement (2010) The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative Vision. NHS: London [Google Scholar]

- Egbert N, Parrott R (2001) Self-efficacy and rural women's performance of breast and cervical cancer detection practices. Journal Health Commun 6(3): 219–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon D, Foster C (2009) Self-Management Support: A Review of the Evidence. Macmillan Research Unit: University of Southampton [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Roffe E (2009) An exploration of the internet as a self-management resource. J Res Nurs 14(1): 13–24 [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Roffe L, Scott I, Cotterell P (2010) Self-Management of Problems Experienced Following Primary Cancer Treatment: An Exploratory Study. Report for Macmillan Cancer Support: London [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Scott I, Rogers A, Addington-Hall J (2007) Evaluation of Macmillan's Mobile Information Centres. Report for Macmillan Cancer Support

- Foster C, Wright D, Hill H, Hopkinson J, Roffe L (2009) Psychosocial implications of living 5 years or more following a cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the research evidence. Eur J Cancer Care 18: 223–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazin N (2007) Long-term conditions: help patients to help themselves. Health Serv J 117: 28–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2005) From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. National Academies Press: Washington DC [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R (2003) Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58(1): 82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson JB, Corner JL (2006) Helping patients with advanced cancer live with concerns about eating: a challenge for palliative care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage 31(4): 293–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefford M, Karahalios E, Pollard A, Baravelli C, Carey M, Franklin J, Aranda S, Schofield P (2008) Survivorship issues following treatment completion – results from focus groups with Australian cancer survivors and health professionals. J Cancer Surviv 2(1): 20–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnilowicz W (2011) Identity and psychological ownership in chronic illness and disease state. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 20(2): 276–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, Lee V, Middleton E, Richardson G, Gardner C, Gately C, Rogers A (2007) The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self care support programme for patients with long-term conditions: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 61(3): 254–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralik D, Koch T, Price K, Howard N (2004) Chronic illness self-management: taking action to create order. J Clin Nurs 13(2): 259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, Appraisal and Coping. Springer: New York [Google Scholar]

- Lent RW (2007) Restoring emotional well-being: a theoretical model. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship, Feuerstein M (ed), pp 231–248. Springer: New York [Google Scholar]

- Lev EL, Daley KM, Conner NE, Reith M, Fernandez C, Owen SV (2001) An intervention to increase quality of life and self-care self-efficacy and decrease symptoms in breast cancer patients. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 15(3): 277–294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K (2002) Partnerships between expert patient and physician. Lancet 359: 814–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska A, Sarkar Y, Knoll N (2007) Received social support, self-efficacy, and finding benefits in disease as predictors of physical functioning and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Patient Educ Couns 66(1): 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan Cancer Support (2008) Two Million Reasons – The Cancer Survivorship Agenda: Why We Need to Support People with or Beyond Cancer. Macmillan Cancer Support: London [Google Scholar]

- Maher EJ, Fenlon D (2010) The psychosocial issues of survivorship in breast cancer. Adv Breast Cancer 7(2): 17–22 [Google Scholar]

- Maher EJ, Makin W (2007) Life after cancer treatment – a spectrum of chronic survivorship conditions. Clin Oncol 19: 743–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Intelligence Network (2010) One, Five and Ten Year Cancer Prevalence. Cancer Network UK [Google Scholar]

- Nord C, Mykletun A, Thorsen L, Bjoro T, Fossa SD (2005) Self-reported health and use of health care services in long term cancer survivors. Int J Cancer 114(2): 307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto I, Wright D, Foster C (2011) Impact of cancer on everyday life: a systematic appraisal of the research evidence. Health Expect; e-pub ahead of print 22 February 2011; doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00662.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen DM, Elverdam B (2007) Cancer survivors’ experience of time: time disruption and time appropriation. J Adv Nurs 57(6): 614–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan-Smith M, Hirschmann K, Lobst W, Battersby M (2006) Teaching residents chronic disease management using the Flinders model. J Cancer Educ 21(2): 60–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C (1999) A framework for the study of coping, illness behaviour and outcomes. J Adv Nurs 29(5): 1246–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL (1987) Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage: Newbury Park, California [Google Scholar]

- van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Voogd AC, Roumen RM, Coebergh JW (2006) Increased health care utilisation among 10-year breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 14(5): 436–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victorson D, Cella D, Wagner L, Kramer L, Smith ML (2007) Measuring quality of life in cancer survivors. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship, Feuerstein M (ed), pp 79–110. Springer: New York [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH (1997) Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 127: 1097–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S, Viergutz G, Tormey D, DeMuln J, Paillen A (1992) Patients’ reactions to completion of adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Nurs Res 42(6): 362–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D, Corner J, Hopkinson J, Foster C (2006) Listening to the views of people affected by cancer about cancer research: an example of participatory research in setting the cancer research agenda. Health Expect 9: 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]