Abstract

The identification of cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) can greatly advance our understanding of gene regulatory mechanisms. Despite the existence of binding sites of more than three transcription factors (TFs) in a CRM, studies in plants often consider only the cooccurrence of binding sites of one or two TFs. In addition, CRM studies in plants are limited to combinations of only a few families of TFs. It is thus not clear how widespread plant TFs work together, which TFs work together to regulate plant genes, and how the combinations of these TFs are shared by different plants. To fill these gaps, we applied a frequent pattern-mining-based approach to identify frequently used cis-regulatory sequence combinations in the promoter sequences of two plant species, Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and poplar (Populus trichocarpa). A cis-regulatory sequence here corresponds to a DNA motif bound by a TF. We identified 18,638 combinations composed of two to six cis-regulatory sequences that are shared by the two plant species. In addition, with known cis-regulatory sequence combinations, gene function annotation, gene expression data, and known functional gene sets, we showed that the functionality of at least 96.8% and 65.2% of these shared combinations in Arabidopsis are partially supported, under a false discovery rate of 0.1 and 0.05, respectively. Finally, we discovered that 796 of the 18,638 combinations might relate to functions that are important in bioenergy research. Our work will facilitate the study of gene transcriptional regulation in plants.

Identifying cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) is important for the understanding of gene transcriptional regulation (Singh, 1998; Yuh et al., 1998; Blanchette et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2010). CRMs are short DNA regions of a few hundred bp that contain multiple transcription factor (TF) binding sites (TFBSs). It is estimated that there are at least 5 times more CRMs than genes in high eukaryotic species (Li et al, 2007). In addition, in high eukaryotes such as metazoans, CRMs instead of individual TFBSs often determine the spatial and temporal expression patterns of neighboring genes (Singh, 1998; Yuh et al., 1998). Therefore, identification of CRMs is crucial for studying gene transcriptional regulation.

In past decades, many studies, both experimental and computational, have identified CRMs in animals (Yuh et al., 1998; Kel-Margoulis et al., 2000; Loots et al., 2000; Frith et al., 2001; Andrioli et al., 2002; Zhou and Wong, 2004; Gupta and Liu, 2005; Blanchette et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2010). Two of the best experimentally studied CRM systems so far may be the CRMs in the Eve gene in Drosophila and those in the Endo16 gene in the sea urchin, in which not only the locations of TFBS instances but also the expression patterns controlled by these CRMs are identified (Howard and Davidson, 2004). Arguably, two databases, the Redfly database for CRMs in Drosophila (Gallo et al., 2006) and the VISTA Enhancer Browser for CRMs in human and mouse (Visel et al., 2007), have the largest collections of experimentally verified CRMs. Besides the experimentally verified CRMs, there are many computational methods developed for CRM prediction (Frith et al., 2002, 2003; Bailey and Noble, 2003; Johansson et al., 2003; Sinha et al., 2003; Alkema et al., 2004; Zhou and Wong, 2004; Gupta and Liu, 2005; Hu et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2010). Several computationally predicted CRM resources are also available (Blanchette et al., 2006; Cai et al., 2010). Computationally predicted CRMs are indispensible and useful due to the enormous size of genomes and the time-consuming process to verify a CRM experimentally.

Compared with CRM studies in animals, research on plant CRMs is limited. Many experimental CRM studies in plants consider cooccurrence of TFBSs of individual TFs with multiple DNA binding domains or a pair of interacting TFs (Solano et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996; Singh, 1998; Kagaya et al., 1999; Nagano et al., 2001; Abe et al., 2003; Konishi and Yanagisawa, 2010), although a plant CRM may consist of TFBSs of three or more TFs (Baudry et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004; Akyildiz et al., 2007; Kawashima et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). In addition, these studies often identify only individual CRMs for individual genes, and only consider a limited number of TFs (Steffens et al., 2005). Furthermore, compared with a large number of computational CRM studies on animals mentioned above, only a couple of computational CRM studies in plants exist. These studies often focus on the identification of two to three TFs that are potentially working together to regulate target genes (Steffens et al., 2005; Vandepoele et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2008; Michael et al., 2008). Therefore, it is not clear how widespread CRMs are in plants, which multiple TFs likely coordinate the transcriptional regulation of their target genes, and how these TF combinations are shared by different plant species.

To fill these gaps in our knowledge about plant CRMs, we developed computational approaches to study plant CRMs in the upstream 1-kb regions of all genes in two plant species, Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and poplar (Populus trichocarpa) by using cis-regulatory sequences from the plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database (Higo et al.,1999). These cis-regulatory sequences in the PLACE database are normally called motifs, each of which represents the common pattern of TFBSs bound by a TF. In this article, we called them cis-regulatory sequences instead of motifs because a PLACE motif often has only a few experimentally verified TFBSs and we often do not know the TF behind a PLACE motif. We found that 18,638 cis-regulatory sequence combinations composed of two to six cis-regulatory sequences are shared by Arabidopsis and poplar. In addition, we discovered that a large number of these shared combinations in Arabidopsis are partially supported by various sources of functional evidence. The developed methods and the predicted shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations will facilitate future CRM studies in plants.

RESULTS

CRMs Are Widespread in Arabidopsis and Poplar Gene Upstream Sequences

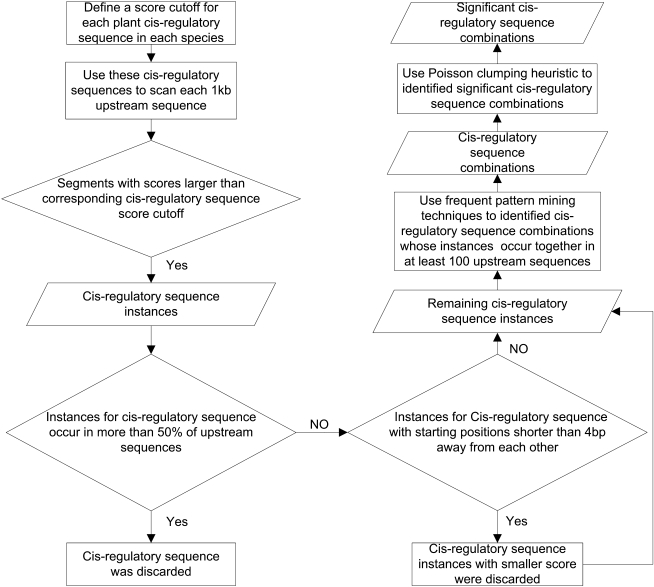

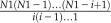

We modified our previously developed method (Cai et al., 2010) for the identification of cis-regulatory sequence combinations and applied it to the upstream 1-kb region of every gene (relative to gene transcription start sites) in Arabidopsis and poplar (Fig. 1). In brief, first, starting from all cis-regulatory sequences in the PLACE database (Higo et al., 1999), we scanned the upstream 1-kb sequence of each gene in the above two plant species. Here a cis-regulatory sequence is a motif in the PLACE database (Higo et al., 1999), which is represented as consensus sequence such as RTACGTGGCR. It is also worth pointing out that scanning 1-kb-long sequences with cis-regulatory sequences will result in many false-positive cis-regulatory sequence instances, which we filtered below by considering cooccurrence of these instances in a large number of sequences and by assessing the statistical significance of this cooccurrence. Second, we identified individual cis-regulatory sequence combinations composed of multiple cis-regulatory sequences, whose instances cooccurred in upstream 1-kb sequences of at least 100 genes in one species. Third, we assessed the statistical significance of these combinations by the Poisson clumping heuristic approximation (Aldous, 1989). Finally, significant cis-regulatory sequence combinations were reported as the final predicted combinations. The upstream 1-kb sequences containing instances of a cis-regulatory sequence combination were considered as CRMs of this combination and the genes containing CRMs of a combination were taken as target genes of this combination. See “Materials and Methods” for details.

Figure 1.

The procedure of predicting shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations by Arabidopsis and poplar.

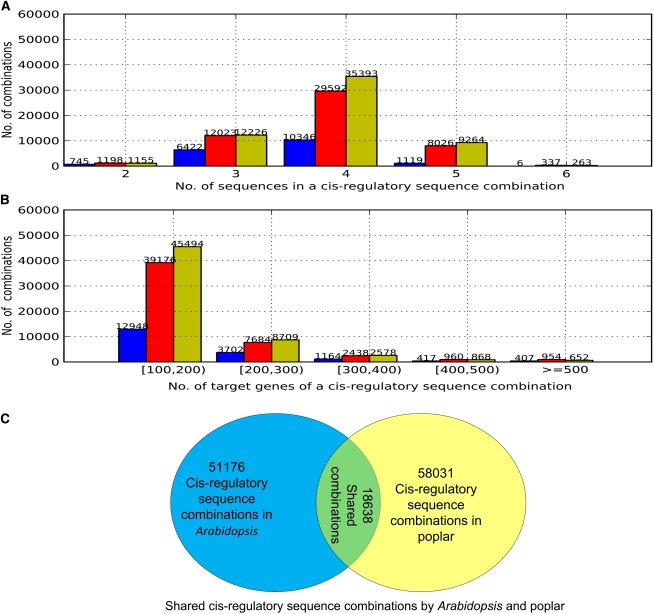

In total, we identified 51,176 cis-regulatory sequence combinations in 92.2% of Arabidopsis genes. These combinations in Arabidopsis consist of two to six cis-regulatory sequences, and 3.88 cis-regulatory sequences on average (Fig. 2). Similarly, we identified 58,031 cis-regulatory sequence combinations in 98.2% of genes in poplar. These poplar combinations consist of two to six cis-regulatory sequences, and 3.91 cis-regulatory sequences on average (Fig. 2). Among all these cis-regulatory sequence combinations, 18,638 combinations are shared by Arabidopsis and poplar. Here a shared combination has exactly the same cis-regulatory sequence combination in the two species, but the majority of its target genes in Arabidopsis may not be orthologous to its target genes in poplar. In fact, for a shared cis-regulatory sequence combination, on average, only 33.3% of its target genes in Arabidopsis have defined orthologous genes in poplar in the Inparanoid database (Ostlund et al., 2010). In addition, for a shared combination, among the target genes with orthology information in the two species, no more than 13.6% of its target genes in Arabidopsis are orthologous to its target genes in poplar. These percentages could be higher, since we have no orthology information for the majority of genes in the two species. Because we identified these combinations in the two species separately, the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations are likely biologically meaningful. See the Supplemental File S1 for all 18,638 combinations and their target genes.

Figure 2.

The number of motifs and target genes for a cis-regulatory sequence combination. A, The distribution of the number of motifs in a TF combination. Each group of three bars above a number from left to right is for shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations, combinations in Arabidopsis, and combinations in poplar, respectively. B, The distribution of the number of target genes in a cis-regulatory sequence combination. Each group of three bars above an interval from left to right is for shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations, combinations in Arabidopsis, and combinations in poplar, respectively. C, Shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations between Arabidopsis and poplar. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Shared Cis-Regulatory Sequence Combinations Are Supported by Known Combinations

To assess the reliability of the above 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations, we compared these combinations with known cis-regulatory sequence combinations. Many experimental studies have identified cooccurring TFBSs of a pair of interacting TFs or individual TFs with multiple DNA binding domains in plants (Solano et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996; Davies et al., 1996; Singh, 1998; Chen and Singh, 1999; Kagaya et al., 1999; Yanagisawa and Schmidt, 1999; Nagano et al., 2001; Abe et al., 2003; Baudry et al., 2004; Konishi and Yanagisawa, 2010). In Table I, we list seven well-known cis-regulatory sequence combinations. TF or TFBS combinations were considered as cis-regulatory sequence combinations here since each TF or TFBS corresponds to a cis-regulatory sequence. There are other known TF combinations as well. However, cis-regulatory sequence information for known TF combinations is not always available. In case that there are known cis-regulatory sequences for TFs, it is difficult to match these cis-regulatory sequences with the PLACE cis-regulatory sequences we used due to different degrees of mismatches between the cis-regulatory sequences. Therefore, we only used the seven known cis-regulatory sequence combinations in Table I.

Table I. Comparison with seven well-known combinations.

The predicted combinations mentioned in the third column contain the known combinations mentioned in the first two columns.

| InformationKnownTF Combinations | Recognition Sequences | No. of Predicted Combinations | Inclusion of Known Target Genes |

| bHLH + MYB | bHLH-CANNTG, MYB-A/TAACCA, or C/TAACG/TG | 32 | AT5G25610 is found to be the target gene of 26 predicted combinations |

| bZIP + Dof | bZIP-ACGT, Dof-AAAG | 656 | AT1G78380 is found to be the target gene of 38 predicted combination |

| MADS + MADS | MADS-CArG box | 2 | AT3G54340 is found to be the target gene of two predicted combinations |

| bZIP + bZIP | bZIP-ACGT, bZIP-ACGT | 429 | AT2G47730 is found to be the target gene of 38 predicted combinations |

| bZIP + MYB | Bzip-ACGT, MYB-CANNTG | 707 | AT5G13930 is found to be the target gene of 22 predicted combinations |

| RAV1 | RAV1-CAACA, RAV1-CACCTG | 2 | AT2G26710 is found to be the target gene of two predicted combinations |

| ZmHOX2a | ZmHox2a HD1-TCCT, ZmHox2a HD2-GATC | 5 | No known target gene information available in Arabidopsis |

We found that our approach predicted all seven known combinations. For each known combination, there are two or more predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations that contain this known combination. For instance, for the known bHLH-MYB (MYC-MYB) combination, 32 predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations contain two motifs from the bHLH and MYB families, respectively. Multiple predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations are consistent with a known combination because different TFs in the same family may bind different motifs. In addition, additional cis-regulatory sequences together with the same known combinations form different predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations, which regulate different target genes. For instance, M9269 (composed of three cis-regulatory sequences AAATTAACCAA [LBOXLERBCS], CTCAAGTGA [SORLIP3AT], and TACGTGTC [ABREMOTIFAOSOSEM]) and M9270 (composed of the cis-regulatory sequences AAATTAACCAA [LBOXLERBCS], CTCAAGTGA [SORLIP3AT], and TTCCCTGTT [ANAERO5CONSENSUS]) are two predicted combinations that overlap with the known combination bHLH-MYB (composed of the PLACE motifs LBOXLERBCS and SORLIP3AT). M9269 and M9270 regulate 108 and 110 target genes, respectively. However, only 22 target genes are regulated by both combinations (see Supplemental File S2).

Since the predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations include additional cis-regulatory sequences, we further investigated whether there is functional evidence to support the addition of other cis-regulatory sequences. We found that this is indeed the case for at least several predicted combinations. For instance, two predicted combinations, M9269 and M9274, contain the known bHLH-MYB combination. Besides the two PLACE motifs SORLIP3AT and LBOXLERBCS that correspond to a bHLH TF and an MYB TF, M9269 and M9274 contain an extra cis-regulatory sequence TACGTGTC (ABREMOTIFAOSOSEM) and CAATNATTG (ATHB5ATCORE), respectively. The bHLH and MYB function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid (ABA) signaling (Abe et al., 2003). The extra motif ABREMOTIFAOSOSEM in M9269 is also related to ABA signaling (Hobo et al., 1999). Similarly, the TF that binds the extra motif ATHB5ATCORE in M9274 is a homeodomain-Leu zipper protein, ATHB5 (Johannesson et al., 2001), which relates to the ABA signaling as well (Johannesson et al., 2003). Therefore, the function of two extra cis-regulatory sequences is consistent with that of the known combinations, both of which relate to ABA signaling.

Besides predicting known cis-regulatory sequence combinations, we also predicted known target genes as target genes of the corresponding predicted combinations. For six out of seven known combinations in Table I, we predicted at least one known target gene as a target gene of multiple corresponding predicted combinations. Note that not all known target genes are included in our prediction. For instance, AT1G61720 is a target gene of the known combination bHLH and MYB (Debeaujon et al., 2003), and was not predicted as a target gene of any corresponding predicted combination. The lack of known target genes could be due to the limited number of known motifs in the PLACE database (only 469 motifs) and upstream sequences (1 kb) used. It could also be a result of the choice of parameters used in the MOPAT software (Hu et al., 2008). See Table I and the Supplemental File S2 for the target genes and the details of comparisons of predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations with known combinations.

Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis Supports Shared Cis-Regulatory Sequence Combinations

To investigate whether the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations make sense, we also performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis (Boyle et al., 2004) on the target genes of each of the 18,638 cis-regulatory sequence combinations in Arabidopsis. The GO enrichment analysis is to assess whether a group of genes significantly shares any function, where a function is described by a standard GO term. That is, we want to check whether the target genes of a cis-regulatory sequence combination significantly share any function, represented by GO terms here, when compared with all annotated genes in Arabidopsis. We did GO enrichment analysis for each cis-regulatory combination only in Arabidopsis because the Arabidopsis genome is much better annotated than the poplar genome.

By performing GO enrichment analysis with the tool GOTermFinder (Boyle et al., 2004), we found that target genes of 58.1% and 77.5% of cis-regulatory sequence combinations in Arabidopsis significantly share GO terms, with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. Below, we provide two examples of the predicted combinations with literature support of their functions. Researchers with interest in specific genes will find more supported cis-regulatory sequence combinations in the Supplemental File S1.

Example 1

The cis-regulatory sequence combination M3121 is composed of three PLACE cis-regulatory sequences, TTGCATGACT (SORLREP5AT), ATAAAACGT (SORLREP2AT), and TAAAAGTTAAAAAC (BOX1PVCHS15). SORLREP5AT and SORLREP2AT are known to be phyA-repressed motifs (Hudson and Quail, 2003) and phyA is critical for red or far-red light photoreceptor activities (Dehesh et al., 1993). BOX1PVCHS15 is known to be bound by GT-1 (Villain et al., 1996) and GT-1 is also related to red light and far-red light response (Gilmartin and Chua, 1990; Escobar et al., 2004). Thus, this cis-regulatory sequence combination M3121 is important for the red or far-red light photoreceptor activity and all three cis-regulatory sequences in this combination may interact to regulate their 187 target genes. We found the following GO terms significantly shared by the target genes of this predicted combination: GO:0009883 (red or far-red light photoreceptor activity, P value 8.47E-05) and GO:0008020 (G-protein-coupled photoreceptor activity, P value 1.68E-04). These GO terms of target genes are consistent with the function of the three cis-regulatory sequences in this combination, which supports the functionality of this cis-regulatory sequence combination.

Example 2

The cis-regulatory sequence combination M64 is composed of two cis-regulatory sequences, TGACACGTGGCA (HY5AT) and CCNNNNNNNNNNNNCCACG (UPRMOTIFIIAT). The Arabidopsis bZIP TF HY5 binds to the HY5AT motif (Chattopadhyay et al., 1998). HY5 relates to photomorphogenesis, which means light-mediated development (Hardtke et al., 2000). UPRMOTIFIIAT is a cis-acting element of gene CNX1 (Oh et al., 2003). It has been shown that both CNX1 and HY5 mediate the development of plants in the light (Mangeon et al., 2011). Thus, the function of the two cis-regulatory sequences in this combination is consistent and the two cis-regulatory sequences in this combination may interact to regulate their 245 target genes. We found that the following GO terms are significantly shared by the target genes of this combination: GO:0019684 (photosynthesis, light reaction, P value 2.31E-06), GO:0015979 (photosynthesis, P value 1.41E-08), and GO:0010207 (PSII assembly, P value 6.36E-05). These functions of target genes are consistent with that of cis-regulatory sequences in this combination, which supports the functionality of this combination.

Coexpressed Gene Clusters and Known Functional Gene Sets in Literature Supports Predicted Cis-Regulatory Sequence Combinations Shared between Arabidopsis and Poplar

In addition to GO enrichment analysis, we also compared target genes of the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations with coexpressed gene clusters in Arabidopsis. Since coexpressed target genes are often coregulated (Allocco et al., 2004), the significant overlap of target genes of a cis-regulatory sequence combination with coexpressed gene clusters supports the functionality of the predicted combinations as well. We found that for 954 of the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations, under a FDR of 0.05, their target genes significantly overlap with at least one coexpressed gene cluster from eight microarray datasets. When we changed the FDR to 0.10, we found that target genes of 14,910 combinations significantly overlap with at least one coexpressed gene cluster. The coexpressed gene clusters were listed in the Supplemental File S5. These 954 and 14,910 cis-regulatory sequence combinations could be obtained by sorting corresponding columns in the Supplemental File S1.

In addition, we compared target genes of the 18,636 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations with all gene sets mentioned in the poplar genome article (Tuskan et al., 2006) and are available in the literature. In total, we obtained six and five gene sets in Arabidopsis and in poplar, respectively (Table II, rows 5–15). Each of these 11 gene sets contains genes of a specific function that are important for the production of bioenergy. We found that each of the 11 gene sets enriched the target genes of several cis-regulatory sequence combinations. In total, we obtained 796 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations that are likely to regulate genes in these functional gene sets, which are important for bioenergy research. For instance, target genes of the cis-regulatory sequence combination M164 significantly overlap with the cell wall formation gene set in Arabidopsis. This combination is composed of cis-regulatory sequences CCCACCTACC (ACIPVPAL2) and TCCATGCAT (SPHCOREZMC1). The motif ACIPVPAL2 interacts directly with the PAL2 gene (Phe ammonia-lyase gene family). The PAL2 gene is involved with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway (Hatton et al., 1995). C1, one of the target genes of the motif SPHCOREZMC1, relates to the cell wall formation process (Suzuki et al., 1997; Yamaguchi et al., 2000). Therefore, the two cis-regulatory sequences corresponding to the two motifs both relate to the cell wall formation process, which conforms to the function of genes in this gene set. The Supplemental File S3 provides the details of shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations with target genes significantly overlapping with these 11 gene sets.

Table II. Functional evidence for the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations.

| Functional Evidence Source (ID) | No. Significant Combinations | |

| FDR = 0.05 | FDR = 0.1 | |

| Known TF combinations (0) | 1,603 (8.6%) | |

| GO (1) | 10,840 (58.1%) | 14,455 (77.6%) |

| Gene expression data from the GEO database (2) | 954 (5.12%) | 14,910 (79.5%) |

| Cellulose synthesis gene set of Arabidopsis (wall formation; 3) | 73 (0.392%) | 487 (2.62%) |

| Cellulose synthesis gene set of Populus (wall formation; 4) | 35 (0.188%) | 321 (1.72%) |

| Phenylpropanoid and lignin synthesis gene set of Arabidopsis (wall formation; 5) | 128 (0.687%) | 622 (3.34%) |

| Phenylpropanoid and lignin synthesis gene set of populus (wall formation; 6) | 63 (0.338%) | 102 (0.547%) |

| Terpenoid synthesis gene set of Arabidopsis (secondary metabolism; 7) | 35(0.188%) | 89 (0.478%) |

| Terpenoid synthesis gene set of populus (secondary metablolism; 8) | 13 (0.0697%) | 26 (0.139%) |

| Aux/IAA gene set of Arabidopsis (phytohormones; 9) | 135 (0.724%) | 622 (3.34%) |

| Aux/IAA gene set of populus (phytohormones; 10) | 53 (0.284%) | 351 (1.88%) |

| Voltage-gated ion channel gene set of Arabidopsis (membrane transporter; 11) | 172 (0.922%) | 518 (2.78%) |

| TNL gene set of Arabidopsis (disease resistance; 12) | 81 (0.435%) | 402 (2.15%) |

| TNL gene set of Populus (disease resistance; 13) | 26 (0.139%) | 129 (0.692%) |

| Total | 12,149 (65.2%) | 18,047 (96.8%) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified 18,638 cis-regulatory sequence combinations shared by Arabidopsis and poplar. By comparing these shared combinations with known cis-regulatory sequence combinations, analyzing functional similarity of target genes, comparing target genes with coexpressed gene clusters, and overlapping target genes with known functional gene sets, we have shown that various sources of evidence support the functionality of more than 96.8% and 65.2% of the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations in Arabidopsis, under a FDR of 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. All 18,638 combinations, the sources of functional evidence supporting their functions, and their target genes are in the Supplemental Files S1 to S3.

We compared the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations with seven categories of known combinations. Although all seven categories of known combinations were included in our predictions, not all known specific TF-TF interactions of each type were predicted. For instance, the TF combination OBP1-OBF (Dof-bZIP) has been reported by several articles (Zhang et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996; Yanagisawa and Schmidt, 1999). However, we did not find this specific combination in our predicted combinations that contain cis-regulatory sequences corresponding to bZIP and Dof. The missed specific TF-TF combinations could be due to the reason that we removed many cis-regulatory sequence instances and putative cis-regulatory sequence combinations as well to control false positives.

For the 18,638 cis-regulatory sequence combinations, on average, about two-thirds of their target genes in the two plant species have no orthologous gene information. The incompleteness of orthologous gene information, together with the limited number of known cis-regulatory sequences and the short noncoding sequences around each gene considered, results in fewer than 13.8% of Arabidopsis target genes with defined poplar orthologs orthologous to the corresponding poplar target genes, for each of the 18,638 cis-regulatory sequence combinations. However, we doubt that the percentage of orthologous target genes for most of the shared combinations will be increased significantly with more information, given the long divergence time of the two species. In fact, previous studies have confirmed that substantial changes occur between the target genes of the same TFs (TF combinations) between even closely related species (Borneman et al., 2007; Tuch et al., 2008; Perez and Groisman, 2009).

In each of the 18,638 predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations, there are two or six cis-regulatory sequences. Note that the same sequences may be included in a cis-regulatory sequence combination multiple times, if there are multiple cis-regulatory sequences in the PLACE database corresponding to the same TFs. For instance, two cis-regulatory sequences, GCCACGTGGc (ACGTROOT1) and GCCACGTGGg (ABREAZMRAB28), are likely bound by the same TF. We found instances of these two cis-regulatory sequences cooccuring in 221 1-kb-long upstream sequences. Thus, we predicted a cis-regulatory sequence combination, M103, which consists of the two cis-regulatory sequences. It is worth mentioning that similar cis-regulatory sequences occurring in the same combination is due to their multiple occurrences in 1-kb-long sequences instead of the overlap of their instances, since overlapping instances were removed from the beginning (see “Materials and Methods”). Because of filtering overlapping instances in our method, it is also evident that there could be more TFs in a plant TF combination.

Among the 18,638 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations, 796 combinations are likely to regulate genes that are important in bioenergy research (Table II). These genes are known to relate to cell wall formation, secondary metabolism, phytohormones, membrane transporter, and disease resistance (Tuskan et al., 2006). We found enrichment with genes related to bioenergy production among the target genes of 796 shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations. We have also shown that cis-regulatory sequences in some combinations are consistent with these functions. These 796 predicted cis-regulatory sequence combinations will be useful for generating hypotheses for future bioenergy research.

Our method is useful for genome-wide studies of gene transcriptional regulation in plants. To our knowledge, previous computational methods for plant CRM identification are often restricted to a small group of genes (Vandepoele et al., 2006) or require TFBS cooccurrence in short regions (≤200 bp; Steffens et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2008). In addition, these methods often consider combinations of only two cis-regulatory sequences at a time. Thus, from previous studies, it is not clear how prevalent CRMs are in the plant genomes. Compared with previous methods, our method can identify new cis-regulatory sequence combinations from a large number of motifs (such as all motifs in plants), can consider cis-regulatory sequence combinations composed of any number of motifs, and can identify frequently used cis-regulatory sequence combinations from upstream 1-kb regions of all genes in one or multiple plant species. Our method is thus a useful addition to tools for plant gene regulation studies.

There are several limitations in our current study. We only considered instances of cis-regulatory sequences in the upstream 1 kb of all genes in a species here. It has been shown, however, that TFBSs can be anywhere in the noncoding sequences (Blanchette et al., 2006). In future studies, we should extend our method to include the entire noncoding regions of a plant genome (Cai et al., 2010). In addition, we could consider plant motifs in other databases (Wingender et al., 1996; Lescot et al., 2002; Sandelin et al., 2004) in addition to the PLACE database. This is feasible because the main component of our method, the frequent pattern-mining technique, has been used to effectively deal with a much larger number of different items (cis-regulatory sequences) in transactions (upstream sequences) in the research field of databases (Han et al., 2000; Grahne and Zhu, 2005). Finally, we only examined the shared combinations in two plant species here. With more genomic data such as gene expression data and epigenetic data in Arabidopsis and poplar, we could consider the function of other combinations in individual species as well.

Our study provides a useful method for the study of gene transcriptional regulation in plants. A software package based on the developed method will be freely available at http://www.cs.ucf.edu/∼xiaoman/arabpoplar/webserver. This software package can be readily applied to a genome-wide study of any sequenced plant species. Our study also supplies a valuable resource of predicted CRMs and cis-regulatory sequence combinations in Arabidopsis and poplar. Besides the prediction provided in the supplemental files, we also provided a Web server at http://www.cs.ucf.edu/∼xiaoman/arabpoplar/webserver for researchers to extract TF combinations they are interested in. The predicted CRMs and shared cis-regulatory sequence combinations in two species, despite the support of many sources of evidence, needs to be experimentally validated. We expect that the application of next-generation sequencing techniques to plant genomes will greatly accelerate the validation process and facilitate their use in plant and bioenergy research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Motifs, Genes, Upstream Sequences, and Orthology Information

A set of 469 plant motifs were obtained from the PLACE database (Higo et al., 1999; Supplemental File S4). Detailed description about these PLACE motifs can be retrieved at http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/info.html. These motifs are represented as consensus sequences, in which the most frequent nucleotide(s) at each position of the sequences is given. For instance, the motif for the sequence bound by CBF2 is CCACGTGG. We called these PLACE motifs cis-regulatory sequences in this article.

We obtained all genes and their upstream 1-kb sequences relative to the gene transcriptional start sites in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and poplar (Populus trichocarpa) from the ENSEMBL plant (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html), where the TAIR10 release and the JGI2.0 were used for these two species. In total, we obtained 33,518 and 41,365 genes and their upstream sequences in Arabidopsis and poplar, respectively. Repeats in the upstream sequences were then masked by using RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/). We obtained all pairs of orthologous genes in Arabidopsis and poplar from the Inparanoid database (Ostlund et al., 2010), from which 10,499 pairs of orthologous genes are defined in the two species. These pairs of orthologous genes are composed of 9,707 Arabidopsis genes and 9,941 poplar genes.

Gene Expression Data and Coexpressed Clusters

We obtained gene expression data on the GPL198 platform (Affymetrix Arabidopsis ATH1 genome array) from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (Edgar et al., 2002). Data from the GPL198 platform was used because this microarray platform has the largest number of samples in Arabidopsis. We further filtered data series that have fewer than 10 samples or have not been normalized by the Robust Multichip Average algorithm (Irizarry et al., 2003). We required at least 10 samples in each dataset to ensure more reliable coexpressed gene clusters. The requirement of normalization by Robust Multichip Average will be helpful for others to repeat this study. In this way, we obtained 15 datasets and 292 samples. Because of our interest in development and bioenergy, we further chose time series data and stress-resistance-related data from the 15 datasets. In total, we obtained eight datasets and 188 samples. The series number of these datasets and the number of samples is listed in Supplemental File S5. For each dataset, we calculated the pairwise Pearson’s correlation coefficient for each gene pair and performed hierarchical clustering with complete linkage to obtain coexpressed clusters, pairs of genes in each of which have a Pearson’s correlation coefficient larger than 0.6 or smaller than −0.6. In total, we obtained 2,461 clusters from the eight GEO datasets (Supplemental File S5). In addition to using 0.6 as the correlation coefficient cutoff, we also obtained clusters based on the cutoffs 0.7 and 0.8. The results from different expression correlation coefficient cutoffs were similar. We reported our results based on the cutoff 0.6 in this article without specification.

Identification of Cis-Regulatory Sequence Combinations in 1-kb-Long Upstream Sequences

Previously, we developed an efficient method (Cai et al., 2010) to identify motif combinations in a large number of sequences of 1-kb length, by using 522 known vertebrate motifs from the TRANSFAC database (Wingender et al., 1996). We applied this method here to identify cis-regulatory sequence combinations in upstream 1-kb sequences of all genes in Arabidopsis and poplar with slight modifications. The reason to modify the previous method is that the quality of plant motifs in the PLACE database (Higo et al., 1999) is lower than that in the TRANSFAC database, with a much fewer number of experimentally verified TFBSs for each motif and a consensus representation of motifs in PLACE. The consequence of scanning upstream sequences with low-quality motifs is that many motifs occur in almost every upstream sequence even requiring exact match of consensus sequences. We thus called these plant motif consensuses cis-regulatory sequences. The details of the method follow.

First, we defined a score cutoff for each plant cis-regulatory sequence. To define the score cutoff, we permutated all upstream sequences and then scanned these random sequences in each species separately, with each PLACE cis-regulatory sequence. For each PLACE cis-regulatory sequence, we calculated the score of each segment of length k in the random sequences, where k is the length of the PLACE cis-regulatory sequence. The score is calculated by the following formula:

In this formula, p(b,i) is defined as:

where n is the number of different nucleotides allowed at the i-th position of the PLACE cis-regulatory sequence, z(b,i) is 1 if b is allowed at the i-th position and 0 if b is not allowed, and 0.01 is used as pseudocount to regularize the motif (Claverie and Audic, 1996); f(b) is the frequency of the nucleotide b in upstream sequences. With the score of each segment, we obtained the score distribution of random segments in each species. We then chose the 85% quartile of this distribution as the score cutoff of the corresponding PLACE cis-regulatory sequence in the corresponding species. That is, if a segment has the score larger than this cutoff, this segment is a potential cis-regulatory sequence instance of this PLACE cis-regulatory sequence. This 85% cutoff corresponds to at most one mismatch for 6- to 8-bp-long PLACE cis-regulatory sequences.

Second, we defined cis-regulatory sequence instances of each PLACE cis-regulatory sequence in each upstream sequence. With the PLACE cis-regulatory sequences and their score cutoffs, we scanned each upstream sequence and obtained all segments with scores larger than the corresponding score cutoffs. These segments are called cis-regulatory sequence instances. Note that some cis-regulatory sequence instances overlap with each other. For those overlapping cis-regulatory sequences instances with starting positions shorter than 4-bp away from each other, we only kept the one with the largest score, as in the previous study (Hu et al., 2008). We also removed instances of cis-regulatory sequences whose instances occur in more than 50% of upstream sequences, as these cis-regulatory sequences are too degenerate to be identified in statistically meaningful cis-regulatory sequence combinations. The following cis-regulatory sequence combination analysis is based on the remaining cis-regulatory sequence instances.

Third, we identified cis-regulatory sequence combinations that occur in at least 100 upstream sequences. With cis-regulatory sequence instances in each upstream sequence, we applied frequent pattern-mining techniques (Han et al., 2000; Grahne and Zhu, 2005) to identify cis-regulatory sequence combinations whose cis-regulatory sequence instances cooccur in at least 100 upstream sequences. The frequent pattern-mining techniques were originally developed as a database mining tool to identify frequent combination of patterns in databases (Han et al., 2000). Consider a database containing customer purchase information. With what frequency will a customer who buys item A also buys item B, C,…? The frequent pattern-mining techniques can efficiently solve this type of problem. In our case, the 469 PLACE cis-regulatory sequences correspond to items and upstream sequences correspond to customers. The cis-regulatory sequence instances in an upstream sequence are the exact items this sequence contains.

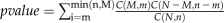

Fourth, we identified significant cis-regulatory sequence combinations by using the Poisson clumping heuristic (Aldous, 1989). For a frequent cis-regulatory sequence combination identified at the third step, say m1, m2,…mn assume it occurs in g out of N1 sequences and λi is the rate parameter of the Poisson process for the motif i. Here N1 is the number of all upstream sequences in one species under consideration. Note that we have considered a sequence and its reverse complement sequence when calculating λi. The probability that instances of all cis-regulatory sequences in this combination occur at least one time in one 1-kb-long upstream sequence is  Therefore, the P value that this combination occurs in g sequences is

Therefore, the P value that this combination occurs in g sequences is  ,where C(N1,i) is defined as

,where C(N1,i) is defined as  Since we generated a large number of combinations at the third step, to control the false-positive rate by Bonferroni correction, we only selected cis-regulatory sequence combinations with the corresponding P value smaller than 0.05/C(469,m), where m is the largest number of motifs in the frequent cis-regulatory sequence combinations output at the third step. For each selected cis-regulatory sequence combination, the upstream sequences containing instances of all cis-regulatory sequences in this combination are defined as CRMs of this combination. Similarly, genes corresponding to these upstream sequences are defined as the target genes of this cis-regulatory sequence combination.

Since we generated a large number of combinations at the third step, to control the false-positive rate by Bonferroni correction, we only selected cis-regulatory sequence combinations with the corresponding P value smaller than 0.05/C(469,m), where m is the largest number of motifs in the frequent cis-regulatory sequence combinations output at the third step. For each selected cis-regulatory sequence combination, the upstream sequences containing instances of all cis-regulatory sequences in this combination are defined as CRMs of this combination. Similarly, genes corresponding to these upstream sequences are defined as the target genes of this cis-regulatory sequence combination.

P Value Calculation for Significant Overlap between Target Genes of a Cis-Regulatory Sequence Combination and a Gene Set of Special Interest

For every cis-regulatory sequence combination, we calculated the significance of overlap between its target genes and each coexpressed gene cluster obtained from the eight microarray expression datasets, by using the hypergeometric test. Assume the set of all genes that are included in the GPL198 platform is S and |S|, the number of genes in S, is equal to N. Given a target gene set S1 of a cis-regulatory sequence combination and a coexpressed gene cluster S2, assume the number of genes in the intersection of the three sets S, S1, and S2 is |S1 ∩ S | = n, |S2 ∩ S| = M, and |S1 ∩ S2| = m, respectively. Then the significance of the overlap of the target gene set S1 and the coexpressed gene cluster S2 is measured by the following P value based on the hypergeometric test:  , where C(x,y) is defined above. Likewise, we calculate the P value of any overlap between target genes of a cis-regulatory sequence combination and a gene set of known function from the literature. With these P values, we then applied the Q-Value software (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003) to all obtained P values and found the P value cutoff, p1, to control the FDR at the level of 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. We then reported all cis-regulatory sequence combinations with the overlapping P values smaller than p1 when compared with a coexpressed cluster or a gene set as the significantly overlapped combinations.

, where C(x,y) is defined above. Likewise, we calculate the P value of any overlap between target genes of a cis-regulatory sequence combination and a gene set of known function from the literature. With these P values, we then applied the Q-Value software (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003) to all obtained P values and found the P value cutoff, p1, to control the FDR at the level of 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. We then reported all cis-regulatory sequence combinations with the overlapping P values smaller than p1 when compared with a coexpressed cluster or a gene set as the significantly overlapped combinations.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental File S1. Shared cis-regulatory sequence combination.

Supplemental File S2. Comparison with known combinations.

Supplemental File S3. Bioenergy-related combinations.

Supplemental File S4. PLACE cis-regulatory sequences.

Supplemental File S5. GEO expression data.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for insightful comments and suggestions, which enabled a significant improvement of the article.

References

- Abe H, Urao T, Ito T, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2003) Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 15: 63–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akyildiz M, Gowik U, Engelmann S, Koczor M, Streubel M, Westhoff P. (2007) Evolution and function of a cis-regulatory module for mesophyll-specific gene expression in the C4 dicot Flaveria trinervia. Plant Cell 19: 3391–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldous D. (1989) Probability Approximations via the Poisson Clumping Heuristic. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp1–15 [Google Scholar]

- Alkema WB, Johansson O, Lagergren J, Wasserman WW. (2004) MSCAN: identification of functional clusters of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res (Web Server issue) 32: W195–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allocco DJ, Kohane IS, Butte AJ. (2004) Quantifying the relationship between co-expression, co-regulation and gene function. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrioli LP, Vasisht V, Theodosopoulou E, Oberstein A, Small S. (2002) Anterior repression of a Drosophila stripe enhancer requires three position-specific mechanisms. Development 129: 4931–4940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Noble WS. (2003) Searching for statistically significant regulatory modules. Bioinformatics (Suppl 2) 19: ii16–ii25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry A, Heim MA, Dubreucq B, Caboche M, Weisshaar B, Lepiniec L. (2004) TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 39: 366–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette M, Bataille AR, Chen X, Poitras C, Laganière J, Lefèbvre C, Deblois G, Giguère V, Ferretti V, Bergeron D, et al. (2006) Genome-wide computational prediction of transcriptional regulatory modules reveals new insights into human gene expression. Genome Res 16: 656–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borneman AR, Gianoulis TA, Zhang ZD, Yu H, Rozowsky J, Seringhaus MR, Wang LY, Gerstein M, Snyder M. (2007) Divergence of transcription factor binding sites across related yeast species. Science 317: 815–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle EI, Weng S, Gollub J, Jin H, Botstein D, Cherry JM, Sherlock G. (2004) GO:TermFinder—open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics 20: 3710–3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Hou L, Su N, Hu H, Deng M, Li X. (2010) Systematic identification of conserved motif modules in the human genome. BMC Genomics 11: 567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WC, Lee TY, Huang HD, Huang HY, Pan RL. (2008) PlantPAN: plant promoter analysis navigator, for identifying combinatorial cis-regulatory elements with distance constraint in plant gene groups. BMC Genomics 9: 561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S, Ang LH, Puente P, Deng XW, Wei N. (1998) Arabidopsis bZIP protein HY5 directly interacts with light-responsive promoters in mediating light control of gene expression. Plant Cell 10: 673–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Chao G, Singh KB. (1996) The promoter of a H2O2-inducible, Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase gene contains closely linked OBF- and OBP1-binding sites. Plant J 10: 955–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Singh KB. (1999) The auxin, hydrogen peroxide and salicylic acid induced expression of the Arabidopsis GST6 promoter is mediated in part by an ocs element. Plant J 19: 667–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie JM, Audic S. (1996) The statistical significance of nucleotide position-weight matrix matches. Comput Appl Biosci 12: 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies B, Egea-Cortines M, de Andrade Silva E, Saedler H, Sommer H. (1996) Multiple interactions amongst floral homeotic MADS box proteins. EMBO J 15: 4330–4343 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeaujon I, Nesi N, Perez P, Devic M, Grandjean O, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. (2003) Proanthocyanidin-accumulating cells in Arabidopsis testa: regulation of differentiation and role in seed development. Plant Cell 15: 2514–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehesh K, Franci C, Parks BM, Seeley KA, Short TW, Tepperman JM, Quail PH. (1993) Arabidopsis HY8 locus encodes phytochrome A. Plant Cell 5: 1081–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 207–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar MA, Franklin KA, Svensson AS, Salter MG, Whitelam GC, Rasmusson AG. (2004) Light regulation of the Arabidopsis respiratory chain: multiple discrete photoreceptor responses contribute to induction of type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenase genes. Plant Physiol 136: 2710–2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith MC, Hansen U, Weng Z. (2001) Detection of cis-element clusters in higher eukaryotic DNA. Bioinformatics 17: 878–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith MC, Li MC, Weng Z. (2003) Cluster-Buster: finding dense clusters of motifs in DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3666–3668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith MC, Spouge JL, Hansen U, Weng Z. (2002) Statistical significance of clusters of motifs represented by position specific scoring matrices in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 3214–3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo SM, Li L, Hu Z, Halfon MS. (2006) REDfly: a regulatory element database for Drosophila. Bioinformatics 22: 381–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin PM, Chua NH. (1990) Localization of a phytochrome-responsive element within the upstream region of pea rbcS-3A. Mol Cell Biol 10: 5565–5568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahne G, Zhu J. (2005) Fast algorithms for frequent itemset mining using FP-trees. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng 17: 1347–1362 [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Liu JS. (2005) De novo cis-regulatory module elicitation for eukaryotic genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7079–7084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Pei J, Yin Y. (2000) Mining frequent patterns without candidate generation. ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Dallas, TX [Google Scholar]

- Hardtke CS, Gohda K, Osterlund MT, Oyama T, Okada K, Deng XW. (2000) HY5 stability and activity in Arabidopsis is regulated by phosphorylation in its COP1 binding domain. EMBO J 19: 4997–5006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton D, Sablowski R, Yung MH, Smith C, Schuch W, Bevan M. (1995) Two classes of cis sequences contribute to tissue-specific expression of a PAL2 promoter in transgenic tobacco. Plant J 7: 859–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. (1999) Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 297–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobo T, Asada M, Kowyama Y, Hattori T. (1999) ACGT-containing abscisic acid response element (ABRE) and coupling element 3 (CE3) are functionally equivalent. Plant J 19: 679–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard ML, Davidson EH. (2004) cis-Regulatory control circuits in development. Dev Biol 271: 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Hu H, Li X. (2008) MOPAT: a graph-based method to predict recurrent cis-regulatory modules from known motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 4488–4497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson ME, Quail PH. (2003) Identification of promoter motifs involved in the network of phytochrome A-regulated gene expression by combined analysis of genomic sequence and microarray data. Plant Physiol 133: 1605–1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4: 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson H, Wang Y, Engström P. (2001) DNA-binding and dimerization preferences of Arabidopsis homeodomain-leucine zipper transcription factors in vitro. Plant Mol Biol 45: 63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson H, Wang Y, Hanson J, Engström P. (2003) The Arabidopsis thaliana homeobox gene ATHB5 is a potential regulator of abscisic acid responsiveness in developing seedlings. Plant Mol Biol 51: 719–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson O, Alkema W, Wasserman WW, Lagergren J. (2003) Identification of functional clusters of transcription factor binding motifs in genome sequences: the MSCAN algorithm. Bioinformatics (Suppl 1) 19: i169–i176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagaya Y, Ohmiya K, Hattori T. (1999) RAV1, a novel DNA-binding protein, binds to bipartite recognition sequence through two distinct DNA-binding domains uniquely found in higher plants. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 470–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T, Wang X, Henry KF, Bi Y, Weterings K, Goldberg RB. (2009) Identification of cis-regulatory sequences that activate transcription in the suspensor of plant embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3627–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kel-Margoulis OV, Romashchenko AG, Kolchanov NA, Wingender E, Kel AE. (2000) COMPEL: a database on composite regulatory elements providing combinatorial transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 311–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Lee SH, Park KY. (2004) A leader intron and 115-bp promoter region necessary for expression of the carnation S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene in the pollen of transgenic tobacco. FEBS Lett 578: 229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M, Yanagisawa S. (2010) Identification of a nitrate-responsive cis-element in the Arabidopsis NIR1 promoter defines the presence of multiple cis-regulatory elements for nitrogen response. Plant J 63: 269–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P, Rombauts S. (2002) PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 325–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhu Q, He X, Sinha S, Halfon MS. (2007) Large-scale analysis of transcriptional cis-regulatory modules reveals both common features and distinct subclasses. Genome Biol 8: R101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots GG, Locksley RM, Blankespoor CM, Wang ZE, Miller W, Rubin EM, Frazer KA. (2000) Identification of a coordinate regulator of interleukins 4, 13, and 5 by cross-species sequence comparisons. Science 288: 136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeon A, Bell EM, Lin WC, Jablonska B, Springer PS. (2011) Misregulation of the LOB domain gene DDA1 suggests possible functions in auxin signalling and photomorphogenesis. J Exp Bot 62: 221–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael TP, Mockler TC, Breton G, McEntee C, Byer A, Trout JD, Hazen SP, Shen R, Priest HD, Sullivan CM, et al. (2008) Network discovery pipeline elucidates conserved time-of-day-specific cis-regulatory modules. PLoS Genet 4: e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano Y, Inaba T, Furuhashi H, Sasaki Y. (2001) Trihelix DNA-binding protein with specificities for two distinct cis-elements: both important for light down-regulated and dark-inducible gene expression in higher plants. J Biol Chem 276: 22238–22243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DH, Kwon CS, Sano H, Chung WI, Koizumi N. (2003) Conservation between animals and plants of the cis-acting element involved in the unfolded protein response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 301: 225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund G, Schmitt T, Forslund K, Köstler T, Messina DN, Roopra S, Frings O, Sonnhammer EL. (2010) InParanoid 7: new algorithms and tools for eukaryotic orthology analysis. Nucleic Acids Res (Database issue) 38: D196–D203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JC, Groisman EA. (2009) Evolution of transcriptional regulatory circuits in bacteria. Cell 138: 233–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engström P, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B. (2004) JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res (Database issue) 32: D91–D94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KB. (1998) Transcriptional regulation in plants: the importance of combinatorial control. Plant Physiol 118: 1111–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, van Nimwegen E, Siggia ED. (2003) A probabilistic method to detect regulatory modules. Bioinformatics (Suppl 1) 19: i292–i301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Nieto C, Avila J, Cañas L, Diaz I, Paz-Ares J. (1995) Dual DNA binding specificity of a petal epidermis-specific MYB transcription factor (MYB.Ph3) from Petunia hybrida. EMBO J 14: 1773–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens NO, Galuschka C, Schindler M, Bülow L, Hehl R. (2005) AthaMap web tools for database-assisted identification of combinatorial cis-regulatory elements and the display of highly conserved transcription factor binding sites in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res (Web Server issue) 33: W397–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. (2003) Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9440–9445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Kao CY, McCarty DR. (1997) The conserved B3 domain of VIVIPAROUS1 has a cooperative DNA binding activity. Plant Cell 9: 799–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch BB, Li H, Johnson AD. (2008) Evolution of eukaryotic transcription circuits. Science 319: 1797–1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A, et al. (2006) The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313: 1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele K, Casneuf T, Van de Peer Y. (2006) Identification of novel regulatory modules in dicotyledonous plants using expression data and comparative genomics. Genome Biol 7: R103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villain P, Mache R, Zhou DX. (1996) The mechanism of GT element-mediated cell type-specific transcriptional control. J Biol Chem 271: 32593–32598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visel A, Minovitsky S, Dubchak I, Pennacchio LA. (2007) VISTA Enhancer Browser—a database of tissue-specific human enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res (Database issue) 35: D88–D92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Guan P, Chen M, Xing X, Zhang Y, Crawford NM. (2010) Multiple regulatory elements in the Arabidopsis NIA1 promoter act synergistically to form a nitrate enhancer. Plant Physiol 154: 423–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingender E, Dietze P, Karas H, Knüppel R. (1996) TRANSFAC: a database on transcription factors and their DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 238–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Nakamura T, Kusano T, Sano H. (2000) Three Arabidopsis genes encoding proteins with differential activities for cysteine synthase and beta-cyanoalanine synthase. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 465–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa S, Schmidt RJ. (1999) Diversity and similarity among recognition sequences of Dof transcription factors. Plant J 17: 209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuh CH, Bolouri H, Davidson EH. (1998) Genomic cis-regulatory logic: experimental and computational analysis of a sea urchin gene. Science 279: 1896–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Chen W, Foley RC, Büttner M, Singh KB. (1995) Interactions between distinct types of DNA binding proteins enhance binding to ocs element promoter sequences. Plant Cell 7: 2241–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Wong WH. (2004) CisModule: de novo discovery of cis-regulatory modules by hierarchical mixture modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12114–12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]