Abstract

Leaves are the most important, fundamental units of organogenesis in plants. Although the basic form of a leaf is clearly divided into the leaf blade and leaf petiole, no study has yet revealed how these are differentiated from a leaf primordium. We analyzed the spatiotemporal pattern of mitotic activity in leaf primordia of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) in detail using molecular markers in combination with clonal analysis. We found that the proliferative zone is established after a short interval following the occurrence of a rod-shaped early leaf primordium; it is separated spatially from the shoot apical meristem and seen at the junction region between the leaf blade and leaf petiole and produces both leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells. This proliferative region in leaf primordia is marked by activity of the ANGUSTIFOLIA3 (AN3) promoter as a whole and seems to be differentiated into several spatial compartments: activities of the CYCLIN D4;2 promoter and SPATULA enhancer mark parts of it specifically. Detailed analyses of the an3 and blade-on-petiole mutations further support the idea that organogenesis of the leaf blade and leaf petiole is critically dependent on the correct spatial regulation of the proliferative region of leaf primordia. Thus, the proliferative zone of leaf primordia is spatially differentiated and supplies both the leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells.

A major source of diversity in flowering plant form is the striking variation in leaf shape and size (Dengler and Tsukaya, 2001; Tsukaya, 2006). Thus, leaves may be suitable targets for examining the developmental mechanisms in plants.

Plants have three major organs: leaves, stems, and roots. Among them, stems and roots are directly produced by the activity of the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and root apical meristem (RAM), respectively. SAM and RAM share similar mechanisms to establish and maintain the stem cells they harbor. Both have an organizing center that is marked by WUSCHEL (WUS) or WUS-RELATED HOMEOBOX5 expression and is regulated by intercellular signaling involving receptor-like kinases and their ligands, such as CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and CLV2, and CLV3/EMBRYO-SURROUNDING REGION PROTEIN-related peptides (for review, see Miwa et al., 2009). Current studies of SAM using model plants propose a view that stem cells localized at the central zone of SAM produce transit-amplifying (TA) cells that are fated for differentiation with an ability to form lateral organs (for review, see Gross-Hardt and Laux, 2003; Scheres, 2007).

In contrast to SAM and RAM, cell proliferation activity in leaf primordia is determinate; thus, one would assume that leaf primordia are a mass of proliferating cells that have the nature of TA-like cells. In an extreme viewpoint, leaf primordia are treated as direct products of TA cells, from the SAM. In contrast, classical morphological and histological observations and recent molecular developmental analyses suggest that a series of organogenesis steps in the leaf primordium depends on several distinct meristematic activities that are established after the initiation of leaf primordia. That is, the plate meristem, marginal meristem, and adaxial meristem have been defined in leaf primordia from classical anatomy (Esau, 1977). The plate meristem is a meristematic tissue consisting of parallel layers of cells dividing anticlinally (perpendicular to the leaf surface) and contributes to the major part of leaf growth. The marginal meristem is located at the leaf margin, between the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces, and is thought to have the potential to initiate the regular array of tissue layers within the leaf. In the leaf primordia of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), the role of the marginal meristem on leaf morphogenesis is believed to be limited (Donnelly et al., 1999). The adaxial meristem is a meristematic tissue on the adaxial side of a young leaf primordium that contributes to the increase in the thickness of a leaf. Recent molecular analyses suggest that so-called dispersed meristematic cells within a leaf primordium also contribute to leaf growth (White, 2006). The meristems described above would be recognized, in a broad sense, as intercalary meristems: they are meristematic tissues some distance away from the SAM and reside in a differentiating organ (Esau, 1977). If so, these tissues in leaf primordia may have a different nature from TA cells. Large gaps, however, exist between classic and modern viewpoints on the organogenesis of leaf primordia.

To address this issue, genes responsible for cell proliferation in leaf primordia would be useful genetic tools. Several activators of cell proliferation in leaf primordia have been reported from Arabidopsis: for example, an AP2/ERF transcription factor (AINTEGUMENTA [ANT]), a nuclear factor of unknown function (ARGOS), a cytochrome P450 (KLUH/CYP78A5), C2H2 zinc finger JAGGED, and a subunit of the Mediator complex STRUWWELPETER (Mizukami and Fischer, 2000; Autran et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2003; Dinneny et al., 2004; Ohno et al., 2004; Anastasiou et al., 2007). Additionally, a putative transcription coactivator, ANGUSTIFOLIA3 (AN3), also known as GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR1 (GIF1; Kim and Kende, 2004), and one of its interaction partners, GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR5 (AtGRF5), promote cell proliferation (Horiguchi et al., 2005). Other members of the GIF family, GIF2 and GIF3, also positively regulate cell proliferation in a redundant fashion (Lee et al., 2009). Importantly, AN3 was recently found to be involved in not only cell proliferation in leaf primordia but also the control of adaxial-abaxial identity in leaves (Horiguchi et al., 2011).

Several negative regulators of cell proliferation in leaf primordia have also been reported from Arabidopsis. These include the microRNA miR396, which represses the expression of most members of the AtGRF family (Jones-Rhoades and Bartel, 2004; Liu et al., 2009; Rodriguez et al., 2010), several members of class II TEOSINTE BRANCHED1, CYCLOIDEA, PCFs, which are targeted by the microRNA JAW (Palatnik et al., 2003), AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2, which negatively regulates the expression of ANT (Horiguchi et al., 2006; Schruff et al., 2006), a short polypeptide, ROTUNDIFOLIA4 (Narita et al., 2004; Ikeuchi et al., 2011), two TIFY-type transcription factors, PEAPOD1 and PEAPOD2 (White, 2006), an E3 ubiquitin ligase, BIG BROTHER (Disch et al., 2006), and two putative ubiquitin receptors, DA1 and DA1-related (Li et al., 2008). Recently, we showed that SPATULA (SPT) functions as a repressor of leaf growth by restricting meristematic region size in young leaf primordia (Ichihashi et al., 2010). Appropriate usage of such genetic tools should provide a powerful strategy to fill in the gaps between classical and modern understandings of organogenesis in leaf primordia.

In understanding leaf morphogenesis, another overlooked problem exists. The basic form of a leaf is clearly divided into two compartments: the leaf blade and the leaf petiole (Tsukaya, 2006). These two compartments differ both in structure and physiology. The leaf blade has a wide, flat laminar structure within which several layers of palisade and spongy tissue cells efficiently absorb light. The leaf petiole has a stem-like role in the sense that it physically supports the leaf blade and has an axial structure without lamina. Moreover, photomorphogenesis mechanisms also differ between the leaf blade and leaf petiole (Tsukaya et al., 2002; Kozuka et al., 2005, 2010). Despite these structural and physiological differences, most developmental analyses, in terms of cell proliferation within leaf primordia, have focused only on the leaf blade. For example, a previous study using pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS activity, which marks cells in G2/M phases, showed a gradient of mitotic activity along the proximal-distal axis in leaf primordia (Donnelly et al., 1999). From this result, one might assume that leaf cells are supplied from the basal-most region of a leaf primordium composed of TA cells, as an oversimplification. However, the lack of detailed observations in the leaf petiole region in the primordia makes it difficult to judge whether such an assumption is correct. We do not yet know whether the leaf blade and leaf petiole are formed concomitantly or sequentially or where the cells that constitute the leaf blade and leaf petiole originate from in the leaf primordium.

To investigate the developmental origin of the two leaf compartments, the leaf blade and the leaf petiole, we carried out detailed analyses of spatiotemporal patterns of mitotic activity during leaf development using molecular markers in combination with clonal analysis. As a result, we found a unique proliferative zone maintained between the developing leaf blade and leaf petiole. This report describes the nature and role of the proliferative region in leaf primordia.

RESULTS

Characterization of the Leaf Blade and Leaf Petiole in Mature Leaf

To characterize structural features of the leaf blade and leaf petiole, as a first step, we observed epidermal and palisade cells and venation pattern in the first set of mature leaves in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1). The leaf blade expanded two-dimensionally, having central and lateral veins, while the leaf petiole had an elongated axial structure with only one central vein (Fig. 1A). At the cellular level, the leaf blade is well known to have jigsaw puzzle-like epidermal cells (Fig. 1B) and round palisade cells (Fig. 1C), while the leaf petiole has large and cylindrical epidermal and palisade cells aligned in obvious cell files (Fig. 1, G and H). Marginal cells were the exception: highly elongated marginal cells were almost equivalent in shape, regardless of the position in a leaf (Fig. 1F), as described previously (Kawamura et al., 2010). Importantly, no clear boundary existed between the leaf blade and leaf petiole in terms of the shape of epidermal or mesophyll cells: in the junction region, the cell shapes were intermediate between those found in the leaf blade and leaf petiole (Fig. 1, D and E). In the following analyses, we used the above-mentioned morphological characteristics for identification of the leaf blade and leaf petiole.

Figure 1.

Characterization of the leaf blade and leaf petiole. A, Cleared mature first leaf harvested at 20 DAS. The arrow indicates the leaf blade/petiole junction region. B to H, Adaxial epidermal surface (B, D, and G) and paradermal views of palisade cells (C, E, and H). The leaf blade region (B and C), leaf blade/petiole junction region (D and E), and leaf petiole region (G and H) are shown. F shows the epidermal surface of the margin at the leaf blade/petiole junction region. Bars = 1 mm (A) and 100 μm (B–H).

Development of the Leaf Blade and Leaf Petiole

We next reexamined the early development of leaf primordia using a pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS transgenic line, in which G2/M cells can be visualized (Donnelly et al., 1999), and an improved modified pseudo-Schiff propidium iodide (mPS-PI) technique, originally reported by Truernit et al. (2008), with special emphasis on development of the leaf petiole region. We found that leaf primordia emerged at the periphery of the SAM, with intensified cell expansion at 2 d after sowing (DAS; Fig. 2, A and B). In leaf primordia at 3 DAS, mitotic cells were found to be distributed almost uniformly in the leaf primordia (Fig. 2C), but differences in cell shape and arrangement could already be recognized between the tip and base of the leaf primordium (Fig. 2, D and E). This was the first developmental event we identified in relation to the differentiation of the leaf blade and leaf petiole. That is, the apical part of the leaf primordium (apical domain) had small, nonpolarized cells with longitudinal, transverse, and oblique arrangements of cross-walls relative to the proximal-distal axis, while the basal part of the leaf primordium (basal domain) had large, longitudinally polarized cells, with a parallel arrangement to the proximal-distal axis. After differentiation of the two regions, cell proliferation in the leaf primordium appeared to accelerate, and the morphology of the leaf blade/petiole junction became more conspicuous (Fig. 2, F and G).

Figure 2.

Development of the leaf blade and leaf petiole. A to H are roughly arranged in accordance with the developmental stages. A, B, D, and E, mPS-PI-stained shoot apex and leaf primordia showing cell arrangements. A and B, Shoot apex at 2 DAS. Optical sections in B were made from the regions indicated by the green lines in A, the top in B from the left line in A, and the bottom in B from the right line in A. LP, Leaf primordium; CZ, central zone of the SAM; PZ, peripheral zone of the SAM. Asterisks indicate large leaf primordium cells. D, Palisade layers in the first set of leaf primordia harvested at 3 DAS. a, Apical domain; b, basal domain. E, Palisade layers in the first set of leaf primordia harvested at sequential developmental stages from 2.5 to 4 DAS. C, F, G, H, and I, pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS expression pattern shown as blue staining, in a cleared first set of leaf primordia, harvested at 3 DAS (C), 4 DAS (F), 6 DAS (G), and 7 DAS (H and I). The brackets in E show establishment of the leaf blade/petiole junction region in terms of anatomy. The proliferative region is shown with a bracket in H. I, Magnified view of the leaf blade/petiole junction region in H. Outlines of several cells are traced with black lines. J, Mitotic index (frequency of mitotic cells) and cell size (cell area) along the proximal-distal axis at 7 DAS. Different letters indicate significant differences between them (P < 0.05, Scheffe method). More than 20 leaf primordia were investigated. To quantify cell size, more than 50 palisade cells in the leaf blade and all palisade cells on two cell files next to marginal cells in the leaf petiole were examined in each leaf. Bars = 50 μm (B–F) and 100 μm (G–I).

At 7 DAS, leaf primordia still had mitotic activity. Although a gradient of mitotic cells is known to be distributed basipetally in the developing leaf blade (Donnelly et al., 1999; Fig. 2H), unexpectedly, this trend was reversed in the developing leaf petiole at this stage (Fig. 2H). Specifically, cell proliferation was more active at the leaf blade/petiole junction region than in the distal and proximal parts of the leaf blade and leaf petiole, respectively. This bidirectional trend was clearly shown by determining the mitotic index in different regions of the leaf blade and leaf petiole: it was highest in the junction region of the leaf blade and leaf petiole (Fig. 2J). Very small cells located in the most basal part of the leaf primordia, corresponding to the leaf base (Medford et al., 1992), did not show pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS expression in their nuclei. This result suggests that there is no, or little, cell recruitment from leaf base to leaf primordia, at least in Arabidopsis.

To provide supporting evidence for the finding of the bidirectional cell supply from the leaf blade/petiole junction, we measured the size of mesophyll cells because cell size indicates the cell differentiation level in plant cells (Ferjani et al., 2007). Consistent with changes in the mitotic index, a cell size minimum was found at the junction region of the leaf blade and leaf petiole, while cells of more distal parts of the leaf blade and leaf petiole from the junction had increased sizes (Fig. 2, I and J). In contrast, the number of longitudinal cell files in the basal domain was almost constant throughout development (4 DAS, 9 ± 0.8, versus 20 DAS, 10 ± 1.0; n ≥ 10), and the numbers of leaf-petiole cells per file at 7 and 20 DAS were 35 ± 16 and 124 ± 17, respectively (n ≥ 10; P < 0.01, Student’s t test). Taken together, our observations suggest that leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells could originate from a common, proliferative region located at the leaf blade/petiole junction. If so, this highly mitotic region is like an intercalary meristem (Esau, 1977), distinct from the SAM.

Leaf-Blade and Leaf-Petiole Cells Are Produced in the Leaf Blade/Petiole Junction Region

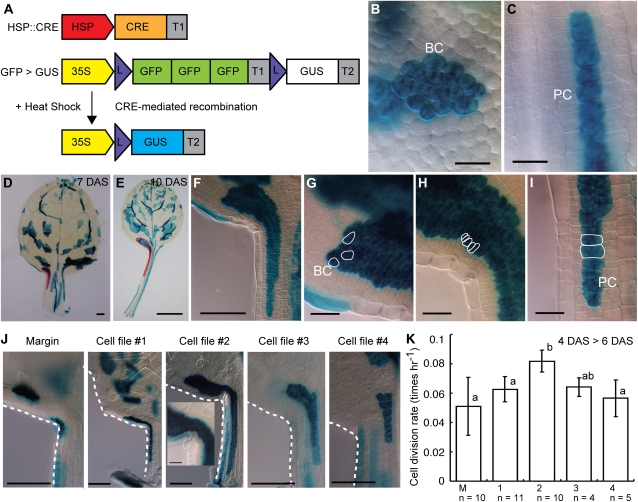

To test this hypothesis, we examined cell lineages in the leaf blade and leaf petiole by clonal analysis using a heat shock-inducible CRE/lox system. In this system, CRE recombinase, induced by heat shock, removes an intervening DNA region between two lox sites in a stochastic manner, resulting in the expression of the GUS reporter gene (Fig. 3A). Under our experimental conditions, the possibility that more than two independent recombination events took place in adjacent cells seemed quite low. Thus, cells in a single sector marked by GUS activity were interpreted as being derived from a single common ancestral cell. Transgenic plants without heat shock showed no induction of a GUS signal in leaves (n = 14). As the developmental stage for CRE induction, we selected 4-DAS plants, which had ovate-formed leaf primordia of approximately 150 μm in length (Fig. 2, E and F).

Figure 3.

Cell lineage of leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells. A, Schematic drawing of the CRE/lox system. Expression of CRE recombinase was under the control of the heat shock promoter (HSP). 3×GFP was placed downstream of a 35S promoter (35S) between two CRE-targeting lox sites (L). GUS was induced after heat shock-dependent recombination by CRE recombinase. T1 and T2 represent the nopaline synthase and 35S terminators, respectively. Colored rectangles depict active genes. B, C, and F to J, Palisade layer in a cleared first set of leaf primordia at 7 DAS. Heat shock (37°C, 90 min, at 4 DAS)-induced sectors of GUS-positive cells are visualized as blue staining. B and C, Magnified views of the sector observed in the leaf blade region (B) and leaf petiole region (C). F to I, Magnified views of the whole sector (F) and the apical (G), middle (H), and basal (I) regions of the sector traced with a red line in D. Outlines of several typical cell shapes are traced with white lines in G to I. BC, Leaf-blade cell; PC, leaf-petiole cell. D and E, Whole images of a cleared first set of leaf primordia at 7 DAS (D) and 10 DAS (E). The outline of a single sector is traced with red lines. J, Magnified views of the leaf blade/petiole junction region. The inset shows a magnified view of the sector. K, Average cell division rate in each cell file. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05, Tukey’s honestly significant difference). Bars = 25 μm (B, C, G–I, and inset in J), 100 μm (D, F, and I), and 1 mm (E).

As a result, small sectors within the leaf blade or leaf petiole regions at 7 DAS were composed of a particular cell type of leaf blade or leaf petiole, respectively (Fig. 3, B and C). Moreover, large sectors, spanning both leaf blade and leaf petiole regions (Fig. 3, D–F), contained three cell types: that is, leaf blade (Fig. 3, B and G), leaf petiole (Fig. 3, C and I), and undifferentiated small cells in the leaf blade/petiole junction region (Fig. 3H). Because this observation was reproducible over all sectors (n ≥ 50), stretched over both the leaf blade and leaf petiole, both cell types, leaf blade and leaf petiole, were likely to have originated from the junction region. Given that the undifferentiated small cells were located in the leaf blade/petiole junction region (Fig. 3H), the ancestral cells of the sectors are probably the proliferative cells localized at the leaf blade/petiole junction, although our clonal analysis could not directly assess where the original marked cells were located. If the ancestral cells already have determined cell fate, GUS lineage sectors are expected to start in the proliferative region and either go into the leaf blade or leaf petiole regions. However, we observed only the sectors stretching over both leaf blade and leaf petiole under a 4-DAS induction treatment. This suggests that 4-DAS leaf primordia might maintain proliferative cells having potential to produce both leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells.

When we observed the large sectors over the leaf blade and leaf petiole, those found in 10-DAS leaves were obviously larger than those in 7-DAS leaves, expanded in both directions toward the apex and base of the leaf primordium (Fig. 3, D–F). The bidirectional gradient in cell size along the proximal-distal axis in the whole leaf primordia (Fig. 2, I and J) was also confirmed in these sectors. Such sectors often contained more than two mesophyll layers (data not shown).

We confirmed active mitosis in these cells, by detecting positive signals not only for the above-mentioned G2/M marker (pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS) but also for DNA synthesis by 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) detection (S phase; Fig. 4, A and B). We also confirmed the new formation of cell walls by staining callose with aniline blue (for M–G1 phase; Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Active proliferation in the leaf blade/petiole junction region. A, DNA replication/synthesis in S-phase cells visualized by an EdU detection system. Green signals in nuclei indicate incorporations of EdU. B, G2/M-phase cells visualized by pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS marker as blue staining. C, New formation of cell walls visualized by staining with aniline blue. Bright blue lines indicate new cell walls that were made in late M phase to early G1 phase. New cell walls in the leaf blade/petiole junction are shown by arrows. All photographs show the first set of leaf primordia harvested at 7 DAS, with the same magnification. Bar = 100 μm.

Then, to characterize mitotic activity within the proliferative region maintained at the leaf blade/petiole junction, a further clonal analysis was carried out focusing on the cell files. Observation of more than 50 sectors over the leaf blade and leaf petiole identified five zonal cell lineages within the proliferative region of leaf primordia (Fig. 3J), suggesting that a leaf could be formed by the assembly of segments at each cell file. We called these cell files marginal, 1, 2, 3, and 4, from the margin to the center of the proliferative region in leaf primordia. To measure the average cell division rate of each cell file for the period from 4 to 6 DAS, we counted the number of GUS-positive cells in a clonal sector over the leaf blade and leaf petiole at 54 h after CRE induction in 4-DAS leaf primordia. The log2-transformed number of cells was divided by 54 h to calculate the average cell division rate (h–1). As a result, we found that cell file 2 showed the highest cell division, having an approximately 40% higher average cell division rate than the other cell files (Fig. 3K). This suggests that the mitotic activity within the proliferative region in leaf primordia could be regulated locally, in a cell file-dependent manner.

Molecular Regionalization in the Proliferative Region of Leaf Primordia

To further characterize the organization of the proliferative region in leaf primordia, we examined the expression patterns of several genes in 6-DAS leaf primordia. We previously screened reporter activities expressed specifically in leaf primordia (Ichihashi et al., 2010) and identified several candidates. Based on those preliminary observations, we used three reporters in this study, as follows.

We previously described that the 2-kb promoter of AN3 (pAN3) expression nicely overlapped with highly proliferating regions in leaf primordia (Horiguchi et al., 2005). As mentioned in the introduction, AN3 is not only important for the acceleration of cell proliferation in leaf primordia but also for the determination of adaxial-abaxial identity in leaves (Horiguchi et al., 2011). In this study, we found that pAN3::GUS was strongest just above the leaf blade/petiole junction (Fig. 5A). This expression pattern was also supported by cross sections and longitudinal sections (Supplemental Fig. S1). On the other hand, as reported previously, the enhancer trap line 576, which has a T-DNA insertion in the promoter region of SPT (Ichihashi et al., 2010), showed GUS marker expression at the marginal region within the proliferative region in leaf primordia (Fig. 5B). This expression region stretched over the leaf blade and leaf petiole but was limited at the margins, suggesting spatial differentiation with the proliferative region in leaf primordia. Additionally, we found that the promoter of a D-type cyclin gene, CYCD4;2 (pCYCD4;2), was active in a specific region of the proliferative region in leaf primordia. This unique expression pattern was first found from rough screening of a promoter::GUS database for cell cycle-related genes that was established at Ghent University. Thus, using the pCYCD4;2::EGFP::GUS transgenic line, a gift from Dr. G.T.S. Beemster, we reexamined the expression pattern of GUS and EGFP in leaf primordia. This transgene is driven by a 2,199-bp 5′ region of CYCD4;2. We found that both GUS and GFP signals were specific to a small number of cells directly adjacent to marginal cells (Fig. 5C). Taken together, the distinct expression patterns of these genes suggest that the proliferative region in leaf primordia could be regionalized by different genetic regulation.

Figure 5.

Molecularly defined zones in the proliferative region of leaf primordia. pAN3::GUS (A), GUS in enhancer trap line 576 (B), and pCYCD4;2::EGFP::GUS (C) expression patterns are shown as blue staining or green signals for the first set of leaf primordia harvested at 6 DAS. Magnified views of the leaf blade/petiole junction region are shown in insets in B and C. Outlines of the leaf margins are traced with black lines. Bars = 100 μm and 50 μm (insets).

Next, we characterized the spatiotemporal expression pattern of the above markers in leaf development. At 3 DAS, pAN3 was expressed strongly in the middle region of the leaf primordia, corresponding to the boundary between the apical and basal domains (Supplemental Fig. S2A), while pCYCD4;2 expression was not detected (Supplemental Fig. S2E). As the leaf blade/petiole junction became conspicuous, pAN3 was expressed strongly at the junction region (Supplemental Fig. S2, B and C); pCYCD4;2 expression was initially detected in cells of the basal domain at 4 DAS (Supplemental Fig. S2F); thus, strong expression was limited to cells at the leaf blade/petiole junction neighboring marginal cells at 6 DAS (Supplemental Fig. S2G). In addition, the establishment of the pCYCD4;2 expression domain was correlated with the period when accelerated cell proliferation started in leaf primordia (compare Supplemental Fig. S2, F and G, with Fig. 2, F and G). Only at this developmental stage did line 576 show GUS expression at the margin of the meristematic region in leaf primordia (Fig. 5B). At 8 DAS, when cell proliferation activity in leaf primordia had almost ceased, pAN3 and pCYCD4;2 expression persisted only at the vascular bundle and leaf blade/petiole junction regions, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2, D and H). Concerning the interaction of the above genes in leaf primordia, notably, AN3 was found to be required for pCYCD4;2 expression in this region (Fig. 6, A–C), suggesting that establishment/maintenance of the cells marked by pCYCD4;2 may depend on AN3 activity.

Figure 6.

Characterization of the an3 mutant. A to C, pCYCD4;2::EGFP::GUS expression patterns are shown as blue staining for the first set of leaf primordia of the wild type (A) and the an3-4 mutant (B and C). Developmental stages in B and C correspond to earlier and later than the stage shown in A, respectively. D, First set of mature leaves from the wild type and an3-4. Incisions were made to flatten the curled leaves. E, The area (white bars) and palisade cell number (gray bars) in the leaf blade of wild-type and an3-4 plants. F, The length (white bars) and palisade cell number per cell file (gray bars) in the leaf petiole of wild-type and an3-4 plants. The first set of leaves from plants at 20 DAS was examined (n = 10; mean ± sd). Data significantly different from those of the wild type are indicated by asterisks (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, Student’s t test). Bars = 100 μm (A–C) and 1 mm (D).

The above observations indicate that pAN3 marks the key proliferative zone at the junction region between the leaf blade and leaf petiole; AN3 function has some roles in spatial differentiation of the proliferative zone. How is the pAN3-marked domain important for leaf morphogenesis? We measured the number of cells of the leaf blade and leaf petiole for the an3 loss-of-function mutant in comparison with the wild type (Fig. 6D). We found that an3 has fewer cells not only in the leaf blade but also in the leaf petiole (Fig. 6, E and F), indicating again that the proliferative region marked by pAN3 is the key for leaf organogenesis, including both the leaf blade and leaf petiole.

Regulation of the Proliferative Region in Leaf Primordia Is Critical for Organogenesis of the Leaf Blade and Leaf Petiole

From our characterizations of the proliferative region in leaf primordia, we proposed that organogenesis of the leaf blade and leaf petiole would critically depend on the appropriate developmental regulation of the proliferative region in leaf primordia marked by pAN3. Supportive evidence for this postulation was obtained from reexamination of the blade-on-petiole1 (bop1) bop2 double mutant, which has been reported to have ectopic leaf blades on the leaf petiole (Ha et al., 2007; Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Characterization of the bop1 bop2 double mutant. A, First mature leaves of the wild type and bop1 bop2 harvested at 20 DAS. B and C, mPS-PI-stained palisade layers in the first set of leaf primordia of bop1 bop2 harvested at 3 DAS (B) and 4 DAS (C). Regions shown with brackets correspond to the leaf blade/petiole junction region that is expected to be established in wild-type leaf primordia (compare with Fig. 2E). D, F and G, pAN3::GUS expression patterns of the wild type and bop1 bop2 shown as blue staining in a cleared first set of leaf primordia at 3 DAS (D), 7 DAS in the wild type (F), and 9 DAS in bop1 bop2 (G). Dashed lines indicate the leaf base. E, First set of leaf primordia of the wild type and bop1 bop2 harvested at 5 DAS. So-called stipules, as markers of leaf base identity, are shown by asterisks. H, Cleared first mature leaf of bop1 bop2 harvested at 20 DAS. The inset shows a magnified view of the leaf-petiole-like region indicated by the box. Arrows indicate lateral veins. I and J, Epidermal (I) and palisade (J) layers in the leaf-petiole-like region of the first set of mature leaves of bop1 bop2 harvested at 20 DAS. Bars = 1 cm (A), 50 μm (B and C), 100 μm (D, F, G, I, and J), 10 μm (E), 1 mm (H), and 500 μm (inset in H).

First, we characterized the establishment of the proliferative region of leaf primordia in bop1 bop2. Although wild-type leaf primordia at 3 and 4 DAS showed distinct apical and basal domains (Fig. 2, D and E), those of bop1 bop2 had relatively uniform, nonpolarized cells and had oblong shape without a clear neck (Fig. 7, B and C), indicating a defect in the differentiation of apical and basal domains. At this developmental stage, the pAN3 expression region abnormally expanded into the basal-most part of bop1 bop2 leaf primordia (Fig. 7D). Additionally, bop1 bop2 did not develop glands of the leaf base, so-called stipules (Fig. 7E), which are markers of the basal region of the leaf primordia in Arabidopsis (Medford et al., 1992), indicating that bop1 bop2 failed to properly establish the leaf base. In a subsequent developmental stage, not only pAN3 (Fig. 7, F and G) but also pCYCD4;2 (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B) marked the basal-most part of the leaf primordia of bop1 bop2. Moreover, the peak of the pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS expression gradient shifted toward the basal-most part of developing leaves in bop1 bop2 (Supplemental Fig. S3, C and D). These observations showed disregulation of the proliferative region in leaf primordia, especially in the basal domain identity in bop1 bop2 leaves, suggesting that BOPs are required for the correct spatial differentiation of the proliferative region in leaf primordia. If organogenesis of the leaf blade and leaf petiole depends on the appropriate spatial regulation of the leaf proliferative region, the bop1 bop2 leaves should have some defects in organogenesis regarding the basal region of the leaf primordia that was determined to be the leaf petiole.

In contrast to this finding, previous reports on bop1 bop2 recognized it to have ectopic leaf blade formation on the leaf petiole (Ha et al., 2003, 2004, 2007). Thus, we recharacterized the leaf-petiole-like region in the first set of mature leaves of bop1 bop2. The leaf-petiole-like region of bop1 bop2 leaves had lateral veins in addition to the central vein (Fig. 7H), as the leaf blade region of the wild type does, while the leaf petiole of the wild type had only one central vein (Fig. 1A). Moreover, the leaf-petiole-like region of bop1 bop2 showed a cellular morphology more similar to the leaf blade/petiole junction region than to the leaf petiole of the wild type in terms of the shapes of epidermal and palisade cells (compare Fig. 7, I and J, with Fig. 1, D, E, G, and H). Thus, we concluded that the mature leaf of bop1 bop2 has a defect in the differentiation of the leaf petiole and develops an abnormal leaf blade.

DISCUSSION

Anatomical Characterization of the Proliferative Region in Leaf Primordia

The basic form of a leaf is clearly divided into two compartments, the leaf blade and the leaf petiole (Fig. 1). In this study, using Arabidopsis leaves, we found a unique proliferative zone within the leaf primordium marked by pAN3 (Fig. 8). We showed that cell proliferation activity in the leaf primordium was established, being spatially independent and isolated from that of the TA cells of the SAM, indicating that it has the nature of an intercalary meristem (Esau, 1977). Leaf initiation at the periphery of the SAM was associated with intensified cell expansion (Fig. 2, A and B), and active cell proliferation in leaf primordia was seen only after this cell expansion stage. The rapid cell expansion in the initiation of leaf primordia was also observed in Anagallis arvensis (Kwiatkowska and Dumais, 2003).

Figure 8.

Model for the proliferative region of leaf primordia. The schematic diagram summarizes functions and spatial differentiation of the proliferative region of leaf primordia. The proliferative region is maintained at the junction region between the leaf blade and the leaf petiole and supplies both leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells. Colors are as follows: orange, pAN3 expression region; red, pCYCD4;2 expression region; blue, SPT enhancer expression region.

Just after initiation, the early leaf primordia differentiated into two regions in terms of cell growth direction: apical and basal domains (Fig. 2D). Coupled with the establishment of the apical and basal domains, a burst of cell proliferation occurred (Fig. 2, E–G). The proliferative region in leaf primordia was maintained at the leaf blade/petiole junction region after this stage until the maturation of the leaf primordia (Fig. 2, H–J) that supplies both the leaf-blade and leaf-petiole cells (Fig. 3). Our previous quantitative analysis of the distributions of mitotic cells showed that the proliferative region in leaf blade of leaf primordia maintains an almost constant size for a certain time period from initiation during leaf development (Kazama et al., 2010). Therefore, the continuous cell supply from the proliferative region, composed of five cell lineages per lateral half (Fig. 3J), likely pushes out cells to the apex and base, leading to the organogenesis of a two-dimensionally expanded leaf blade and longitudinally elongated axial leaf petiole, respectively. Actively dividing cells supplied from this region behave differently between two domains: the leaf blade and leaf petiole. The angle of the cell division plane relative to the longitudinal axis of the leaf primordium becomes variable in the leaf blade region after the start of AN3 expression (Horiguchi et al., 2011), while it is regularly perpendicular to the longitudinal axis in the leaf petiole region. The bidirectional cell supply from single cells aligned laterally at the junction region seems to be plausible based on our available data but remains to be definitively confirmed by further clonal or growth analyses. Our findings on the proliferative region in leaf primordia as described above provide a conceptual advance in understanding shoot morphogenesis: organogenesis of the basic compartments of leaves is achieved within the proliferative region of leaf primordia; that is, it is not a direct product of TA cells from the SAM.

Functional Organization of the Proliferative Region in Leaf Primordia

We found that the differentiation of the apical and basal domains within the proliferative region of leaf primordia was the first developmental event related to the differentiation of the leaf blade and leaf petiole (Fig. 2, D and E). We also found that the proliferative region of leaf primordia contained a heterologous population of proliferating cells in terms of gene expression pattern (Fig. 5) or cell division rate (Fig. 3, J and K). These differentiations within the proliferative region in leaf primordia indicate how the mitotic activity is organized for the organogenesis of basic compartments of leaves, the leaf blade and leaf petiole.

We found that pAN3 well covered the proliferative region in the junction between the leaf blade/petiole (Figs. 2 and 5) and that the loss-of-function mutant an3 had significant defects in the number of cells in both the leaf blade and leaf petiole (Fig. 6, D–F). Moreover, AN3 function was found to be necessary for the correct spatial differentiation of the proliferative region (Figs. 6, A–C, and 7). Recently, the early leaf primordia (3–4 DAS) of an an3 mutant were revealed to be indistinguishable from those of the wild type; AN3 was expressed in leaf primordia but not in the SAM (Horiguchi et al., 2011). These findings suggest that AN3 plays a central role in maintaining the proliferative activity in the proliferative region of leaf primordia.

The proliferative region marked by pAN3 seemed to be differentiated into two compartments, marked by enhancer trap line 576 and pCYCD4;2, respectively (Fig. 5). The enhancer trap line 576 showed GUS marker gene expression at the margin of the proliferative region in leaf primordia (Fig. 5B). We previously showed that line 576 likely reports the expression pattern of SPT (Ichihashi et al., 2010), and a recent study also revealed that the 5′ region of SPT expresses in the basal margin of leaf primordia, which corresponds to the margin of the proliferative region in leaf primordia (Groszmann et al., 2010). Moreover, spt loss-of-function mutants enlarge the size of the proliferative region independently of AN3 activity (Ichihashi et al., 2010). These results suggest that SPT could function at the margin of the proliferative region in leaf primordia, restricting its proliferative field in parallel with AN3. The functional meaning of the specific expression pattern of pCYCD4;2, however, is unclear at present. Loss-of-function mutations of CYCD4;2 and the closely related CYCD4;1 gene do not affect leaf size or shape, but overexpression of CYCD4;2 promotes cell proliferation in leaves (Kono et al., 2007). Additionally, the actual expression pattern of CYCD4;2 may not be identical to that observed in the pCYCD4;2::EGFP::GUS line examined. pCYCD4;2, however, should at least have a specific cis-element that allows gene expression in the small cell population at cell file 1 (Fig. 5C) to be started at a particular stage when accelerated cell division starts. pCYCD4;2 has the potential to be used as a good marker for a particular position and a particular developmental stage in leaf primordia. Notably, AN3 is required for the establishment/maintenance of pCYCD4;2-positive cells (Fig. 6, A–C). The small cell population at cell file 1, and not CYCD4;2 itself, might plausibly depend on AN3 for its establishment and may somehow have a role in the highest mitotic activity in cell file 2 through cell-to-cell communication.

We also found that correct expression patterns of pAN3 and pCYCD4;2 depend on BOP1 and BOP2 (Fig. 7; Supplemental Fig. S3). The bop1 bop2 mutant has a defect in spatial differentiation in leaf primordia and has leaf-blade-like organs only (Fig. 7), in contrast to previous reports (Ha et al., 2003, 2004, 2007). Taken together with the anatomical and clonal data in our study, the proliferative zone found at the junction between the leaf blade/petiole, determined by BOP and covered by AN3, is strongly indicated to be the center functioning primarily in cell supply and cell fate determination for leaf organogenesis (Fig. 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The wild-type accession of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) used in this study was accession Columbia-0. Transgenic plants carrying pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS and pCYCD4;2::EGFP::GUS were gifts from Dr. J.L. Celenza and Dr. G.T.S. Beemster, respectively. The enhancer trap line 576 was initially selected from an enhancer trap collection (Campisi et al., 1999) as exhibiting a GUS expression pattern during early leaf developmental stages (Ichihashi et al., 2010). We also used the pAN3::GUS transgenic line (Horiguchi et al., 2005) and the bop1-4 bop2-11 double mutant (Ha et al., 2007). Plants were grown on rock wool (Nitto Boseki) and watered daily with 0.5 g L–1 Hyponex solution (Hyponex Japan) at 23°C under continuous illumination (approximately 50 μmol m–2 s–1). For histological analyses, wild-type plants, mutants, and transgenic plants were grown side by side in the same container to minimize variables that might arise from differences in the microenvironments of the growth chamber.

Generation of CRE/lox Transgenic Plants

To generate a construct of the heat shock promoter-Cre fusion plasmid pTT222 (HSP::CRE), an AseI fragment of the pCrox plasmid (Hoff et al., 2001), which contains the Cre coding region fused with an N-terminal nuclear localization signal sequence, was first inserted into the NdeI site of the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega) and then cloned as a SpeI-SacI fragment into the Ti plasmid pTT101 (Matsuhara et al., 2000). To generate a construct in which GUS expression was inducible by CRE recombinase-mediated recombination, a 35S terminator of Cauliflower mosaic virus, flanked by two lox sequences, a GUS gene, and a 3×GFP gene, were prepared as follows. The 35S terminator was amplified by PCR using pCAMBIA1200 (http://www.cambia.org/daisy/cambia/585) as a template and the following primer pair: 5′-TCTAGATAACTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTATCTCGAGGATCTGTCGATCGACAAGATCGAG-3′ and 5′-ATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATAATTCGGGGGATCTGGATTTTAGTAC-3′. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector to yield pGEM Lox. The GUS cDNA, flanked by an XhoI site, was amplified using pSMAB704 as a template and the primers 5′-CTCGAGATATGTTACGTCCTGTAGAAAC-3′ and 5′-TCATTGTTTGCCTCCCTGCT-3′ and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector, yielding pGEM GUS. The GFP cDNAs with or without a termination codon and flanked by an XhoI site were amplified from pH35WG (G. Horiguchi and H. Tsukaya, unpublished data) using the following primer pair: 5′-CTCGAGGGAGGCGGTGGAGGCATG-3′ and 5′-GTCGACCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC-3′ (with no termination codon) or 5′-TTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCA-3′ (with a termination codon). These cDNA fragments were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector and designated as pGEM GFP(–) and pGEM GFP(+), respectively. The GFP cDNA without the termination codon was excised by XhoI and SalI and then inserted into the XhoI site of pGEM GFP(+), which was placed in front of the initiation codon of pGEM GFP(+). This step was repeated once more to generate pGEM 3×GFP. The GUS cDNA was excised by XhoI and SalI and inserted into the SalI site of pGEM Lox, which was located behind the second lox site. The resulting vector was designated “pGEM LLG.” The 3×GFP cDNA was excised by XhoI and SalI and then cloned into the XhoI site of pGEM LLG, which was placed between the first lox sequence and the 35S terminator to yield pGEM LLG-G3. Then, a DNA fragment spanning the first lox site, 3×GFP, 35S terminator, the second lox site, and GUS sequence was excised by XbaI and SacI and inserted into the same restriction sites of pSMAB704, yielding pSMAB704 GFP>GUS. Transformation of Arabidopsis was carried out using the floral dip method described by Clough and Bent (1998).

Microscopic Observations

Whole leaves and leaf cells were observed with a stereoscopic microscope (MZ16 F) and a Nomarski differential interference contrast microscope (DM4500 B), respectively (both from Leica Microsystems). Leaves were fixed in a formalin-acetic acid-alcohol (FAA) solution and cleared using a chloral hydrate solution, as described previously (Tsuge et al., 1996). The samples were then photographed using the microscopes, and cell size and leaf size were determined using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij). For each leaf, palisade cells in the subepidermal layer at the center of the leaf blade or leaf petiole between the midvein and the leaf margin were analyzed. GUS activity patterns in leaf primordia were determined as described previously (Donnelly et al., 1999). GFP signal patterns in leaf primordia were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss). Clonal analysis and measurement of average cell division rate within the meristematic region of leaf primordia were carried out using the CRE/lox system (HSP::CRE 222 × GFP>GUS F1 plants).

Cell Cycle Phase Determination

To detect S-phase cells, we used an EdU-based assay method (Kotogány et al., 2010). Seedlings at 7 DAS were incubated in 10 μm EdU (Click-iT EdU Microplate Assay kit; Invitrogen Japan) dissolved in 0.5 g L−1 Hyponex solution for 1 h under illumination in a culture chamber and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (pH 7.0), followed by fixation with 4% (w/v) formaldehyde and 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100 in PBS, for 1 h. Fixed seedlings were washed twice with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min each, then washed again with PBS for 5 min. Shoot apices were then trimmed with forceps and treated with a series of reaction buffers of the Click-iT EdU detection kit (Alexa 488) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Finally, samples were rinsed with PBS for 3 h, then transferred onto slides and covered with a chloral hydrate solution to make the samples transparent. Observation was made with an epifluorescence microscope (MZ16 F; Leica) excited with blue light.

To detect cells under late M to early G1 phase, we visualized new septum walls with aniline blue (Waldeck) according to a method described by Kuwabara and Nagata (2006). Seedlings at 7 DAS were fixed by FAA solution for 1 h, then dehydrated with an ethanol series (50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, 100% [w/v] ethanol) for 10 min each, then transferred to 50% ethanol in PBS buffer. Shoot apices were trimmed with forceps and stained with 0.02% (w/v) aniline blue dissolved in 100 mm K2HPO4 on ice for several hours. Finally, samples were observed with an epifluorescence microscope (MZ16 F; Leica) excited with UV.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Plant materials were fixed in FAA and dehydrated with 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100% (v/v) ethanol. Then, samples were washed in 3-methylbutyl acetate:ethanol (1:1, v/v) and 100% 3-methylbutyl acetate. The samples were frozen and dried (FDU-2100; EYELA), platinum coated (JFC-1300; JEOL), and observed with a scanning electron microscope at 10 kV (JSM-820S; JEOL).

Improved mPS-PI Staining

For the observation of early leaf primordia, we improved the mPS-PI staining method reported by Truernit et al. (2008), as described here. Plant materials were fixed in 50% methanol and 10% acetic acid at 4°C for at least 12 h. Then, samples were transferred to and incubated in 80%, 90%, and 100% (v/v) ethanol at 80°C for 5 min each. Samples were transferred back to 50% methanol and 10% acetic acid and incubated for 1 h. Next, samples were rinsed with water and incubated in 1% periodic acid at room temperature for 40 min. The samples were rinsed again with water and incubated in 1 mg mL−1 propidium iodide aqueous solution for 5 min. The samples were transferred onto slides and covered with a chloral hydrate solution for 30 min, and a coverslip was placed on top before observation with a confocal microscope.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. pAN3::GUS expression shows a gradient at the basal region of leaf primordia.

Supplemental Figure S2. Spatiotemporal expression pattern of pAN3 and pCYCD4;2 in leaf primordia.

Supplemental Figure S3. Expression pattern of molecular markers for the leaf blade/petiole junction region in bop1 bop2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J.L. Celenza (Department of Biology, Boston University), Dr. G.T.S. Beemster (Department of Biology, University of Antwerp), and Dr. C.M. Ha and Dr. J.C. Fletcher (Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley) for kindly providing seeds of a pCYCB1;1::Dbox::GUS transgenic line, a pCYCD4;2::EGFP::GUS transgenic line, and the bop1-4 bop2-11 double mutant, respectively. We also thank Dr. H. Ichikawa (National Institute of Agrobiological Science) for providing pSMAB704, Dr. T. Nakawaga (Department of Molecular and Functional Genomics, Center for Integrated Research in Science, Shimane University) for providing R4pGWB501, Dr. J. Mundy (Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen) for the generous gift of the pCrox plasmid to T.T., and Dr. A. Nakano (Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo) for observations using confocal laser scanning microscopy.

References

- Anastasiou E, Kenz S, Gerstung M, MacLean D, Timmer J, Fleck C, Lenhard M. (2007) Control of plant organ size by KLUH/CYP78A5-dependent intercellular signaling. Dev Cell 13: 843–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autran D, Jonak C, Belcram K, Beemster GT, Kronenberger J, Grandjean O, Inzé D, Traas J. (2002) Cell numbers and leaf development in Arabidopsis: a functional analysis of the STRUWWELPETER gene. EMBO J 21: 6036–6049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi L, Yang Y, Yi Y, Heilig E, Herman B, Cassista AJ, Allen DW, Xiang H, Jack T. (1999) Generation of enhancer trap lines in Arabidopsis and characterization of expression patterns in the inflorescence. Plant J 17: 699–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengler NG, Tsukaya H. (2001) Leaf morphogenesis in dicotyledons: current issues. Int J Plant Sci 162: 459–464 [Google Scholar]

- Dinneny JR, Yadegari R, Fischer RL, Yanofsky MF, Weigel D. (2004) The role of JAGGED in shaping lateral organs. Development 131: 1101–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disch S, Anastasiou E, Sharma VK, Laux T, Fletcher JC, Lenhard M. (2006) The E3 ubiquitin ligase BIG BROTHER controls Arabidopsis organ size in a dosage-dependent manner. Curr Biol 16: 272–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly PM, Bonetta D, Tsukaya H, Dengler RE, Dengler NG. (1999) Cell cycling and cell enlargement in developing leaves of Arabidopsis. Dev Biol 215: 407–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esau K. (1977) Anatomy of Seed Plants. Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- Ferjani A, Horiguchi G, Yano S, Tsukaya H. (2007) Analysis of leaf development in fugu mutants of Arabidopsis reveals three compensation modes that modulate cell expansion in determinate organs. Plant Physiol 144: 988–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Hardt R, Laux T. (2003) Stem cell regulation in the shoot meristem. J Cell Sci 116: 1659–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M, Bylstra Y, Lampugnani ER, Smyth DR. (2010) Regulation of tissue-specific expression of SPATULA, a bHLH gene involved in carpel development, seedling germination, and lateral organ growth in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 61: 1495–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha CM, Jun JH, Nam HG, Fletcher JC. (2004) BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 encodes a BTB/POZ domain protein required for leaf morphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 1361–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha CM, Jun JH, Nam HG, Fletcher JC. (2007) BLADE-ON-PETIOLE 1 and 2 control Arabidopsis lateral organ fate through regulation of LOB domain and adaxial-abaxial polarity genes. Plant Cell 19: 1809–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha CM, Kim G-T, Kim BC, Jun JH, Soh MS, Ueno Y, Machida Y, Tsukaya H, Nam HG. (2003) The BLADE-ON-PETIOLE 1 gene controls leaf pattern formation through the modulation of meristematic activity in Arabidopsis. Development 130: 161–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff T, Schnorr KM, Mundy J. (2001) A recombinase-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant Mol Biol 45: 41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G, Fujikura U, Ferjani A, Ishikawa N, Tsukaya H. (2006) Large-scale histological analysis of leaf mutants using two simple leaf observation methods: identification of novel genetic pathways governing the size and shape of leaves. Plant J 48: 638–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G, Kim G-T, Tsukaya H. (2005) The transcription factor AtGRF5 and the transcription coactivator AN3 regulate cell proliferation in leaf primordia of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 43: 68–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi G, Nakayama H, Ishikawa N, Kubo M, Demura T, Fukuda H, Tsukaya H. (2011) ANGUSTIFOLIA3 plays roles in adaxial/abaxial patterning and growth in leaf morphogenesis. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 112–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Xie Q, Chua NH. (2003) The Arabidopsis auxin-inducible gene ARGOS controls lateral organ size. Plant Cell 15: 1951–1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihashi Y, Horiguchi G, Gleissberg S, Tsukaya H. (2010) The bHLH transcription factor SPATULA controls final leaf size in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 252–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi M, Yamaguchi T, Kazama T, Ito T, Horiguchi G, Tsukaya H. (2011) ROTUNDIFOLIA4 regulates cell proliferation along the body axis in Arabidopsis shoot. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 59–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. (2004) Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol Cell 14: 787–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura E, Horiguchi G, Tsukaya H. (2010) Mechanisms of leaf tooth formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J 62: 429–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama T, Ichihashi Y, Murata S, Tsukaya H. (2010) The mechanism of cell cycle arrest front progression explained by a KLUH/CYP78A5-dependent mobile growth factor in developing leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1046–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kende H. (2004) A transcriptional coactivator, AtGIF1, is involved in regulating leaf growth and morphology in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13374–13379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono A, Umeda-Hara C, Adachi S, Nagata N, Konomi M, Nakagawa T, Uchimiya H, Umeda M. (2007) The Arabidopsis D-type cyclin CYCD4 controls cell division in the stomatal lineage of the hypocotyl epidermis. Plant Cell 19: 1265–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotogány E, Dudits D, Horváth GV, Ayaydin F. (2010) A rapid and robust assay for detection of S-phase cell cycle progression in plant cells and tissues by using ethynyl deoxyuridine. Plant Methods 6: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozuka T, Horiguchi G, Kim G-T, Ohgishi M, Sakai T, Tsukaya H. (2005) The different growth responses of the Arabidopsis thaliana leaf blade and the petiole during shade avoidance are regulated by photoreceptors and sugar. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozuka T, Kobayashi J, Horiguchi G, Demura T, Sakakibara H, Tsukaya H, Nagatani A. (2010) Involvement of auxin and brassinosteroid in the regulation of petiole elongation under the shade. Plant Physiol 153: 1608–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara A, Nagata T. (2006) Cellular basis of developmental plasticity observed in heterophyllous leaf formation of Ludwigia arcuata (Onagraceae). Planta 224: 761–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska D, Dumais J. (2003) Growth and morphogenesis at the vegetative shoot apex of Anagallis arvensis L. J Exp Bot 54: 1585–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Ko J-H, Lee S, Lee Y, Pak J-H, Kim JH. (2009) The Arabidopsis GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR gene family performs an overlapping function in determining organ size as well as multiple developmental properties. Plant Physiol 151: 655–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zheng L, Corke F, Smith C, Bevan MW. (2008) Control of final seed and organ size by the DA1 gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev 22: 1331–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Song Y, Chen Z, Yu D. (2009) Ectopic expression of miR396 suppresses GRF target gene expression and alters leaf growth in Arabidopsis. Physiol Plant 136: 223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhara S, Jingu F, Takahashi T, Komeda Y. (2000) Heat-shock tagging: a simple method for expression and isolation of plant genome DNA flanked by T-DNA insertions. Plant J 22: 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medford JI, Behringer FJ, Callos JD, Feldmann KA. (1992) Normal and abnormal development in the Arabidopsis vegetative shoot apex. Plant Cell 4: 631–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Kinoshita A, Fukuda H, Sawa S. (2009) Plant meristems: CLAVATA3/ESR-related signaling in the shoot apical meristem and the root apical meristem. J Plant Res 122: 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y, Fischer RL. (2000) Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 942–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita NN, Moore S, Horiguchi G, Kubo M, Demura T, Fukuda H, Goodrich J, Tsukaya H. (2004) Overexpression of a novel small peptide ROTUNDIFOLIA4 decreases cell proliferation and alters leaf shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 38: 699–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno CK, Reddy GV, Heisler MG, Meyerowitz EM. (2004) The Arabidopsis JAGGED gene encodes a zinc finger protein that promotes leaf tissue development. Development 131: 1111–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington JC, Weigel D. (2003) Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature 425: 257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez RE, Mecchia MA, Debernardi JM, Schommer C, Weigel D, Palatnik JF. (2010) Control of cell proliferation in Arabidopsis thaliana by microRNA miR396. Development 137: 103–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B. (2007) Stem-cell niches: nursery rhymes across kingdoms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruff MC, Spielman M, Tiwari S, Adams S, Fenby N, Scott RJ. (2006) The AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 gene of Arabidopsis links auxin signalling, cell division, and the size of seeds and other organs. Development 133: 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truernit E, Bauby H, Dubreucq B, Grandjean O, Runions J, Barthélémy J, Palauqui JC. (2008) High-resolution whole-mount imaging of three-dimensional tissue organization and gene expression enables the study of phloem development and structure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 1494–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge T, Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H. (1996) Two independent and polarized processes of cell elongation regulate leaf blade expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Development 122: 1589–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. (2006) Mechanism of leaf-shape determination. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 477–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H, Kozuka T, Kim G-T. (2002) Genetic control of petiole length in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 1221–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DWR. (2006) PEAPOD regulates lamina size and curvature in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 13238–13243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]