Abstract

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway plays an instructional role during development, and is frequently activated in cancer. Ligand-induced pathway activation requires signaling by the transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo), a member of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily. The extracellular (EC) loops of canonical GPCRs harbor cysteine residues that engage in disulfide bonds, affecting active and inactive signaling states through regulating receptor conformation, dimerization and/or ligand binding. Although a functional importance for cysteines localized to the N-terminal extracellular cysteine-rich domain has been described, a functional role for a set of conserved cysteines in the EC loops of Smo has not yet been established. In this study, we mutated each of the conserved EC cysteines, and tested for effects on Hh signal transduction. Cysteine mutagenesis reveals that previously uncharacterized functional roles exist for Smo EC1 and EC2. We provide in vitro and in vivo evidence that EC1 cysteine mutation induces significant Hh-independent Smo signaling, triggering a level of pathway activation similar to that of a maximal Hh response in Drosophila and mammalian systems. Furthermore, we show that a single amino acid change in EC2 attenuates Hh-induced Smo signaling, whereas deletion of the central region of EC2 renders Smo fully active, suggesting that the conformation of EC2 is crucial for regulated Smo activity. Taken together, these findings are consistent with loop cysteines engaging in disulfide bonds that facilitate a Smo conformation that is silent in the absence of Hh, but can transition to a fully active state in response to ligand.

Keywords: Hedgehog, Smoothened, Signal transduction, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

The Hedgehog (Hh) signal transduction pathway plays an essential role in establishing tissue organization during metazoan development (Ingham and McMahon, 2001; Jiang and Hui, 2008). Consistent with this crucial role, familial or sporadic mutation in Hh pathway signaling components contributes to a range of developmental disorders (Cohen, 2010; Johnson et al., 1996). Hh signaling can also contribute to tumor development and progression, being causative in a subset of medulloblastoma (Gottardo and Gajjar, 2008), basal cell carcinoma (Hahn et al., 1996; Unden et al., 1996; Wolter et al., 1997) and rhabdomyosarcoma (Zibat et al., 2010).

Hh pathway activation is controlled by two membrane proteins, the 12-pass transmembrane protein Patched (Ptc), the Hh receptor (Hooper and Scott, 1989; Marigo et al., 1996; Nakano et al., 1989; Stone et al., 1996) and the signal transducer Smoothened (Smo), a member of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily (Alcedo et al., 1996; van den Heuvel and Ingham, 1996). In the absence of Hh, Ptc blocks Smo signaling, in part through regulating its subcellular localization (Rohatgi et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2003). Hh binding to Ptc removes this inhibition (Denef et al., 2000; Torroja et al., 2004), which allows Smo to signal to an intracellular Hh signaling complex (HSC) (Denef et al., 2000; Rohatgi et al., 2007). In Drosophila, the HSC consists of the kinesin-related protein Costal2 (Cos2), the protein kinase Fused (Fu) and the GLI transcription factor, Cubitus interruptus (Ci) (Alexandre et al., 1996; Motzny and Holmgren, 1995; Robbins et al., 1997; Sisson et al., 1997). In the absence of Hh, the HSC targets Ci for proteolytic processing, which converts it to a truncated transcriptional repressor (Aza-Blanc et al., 1997; Robbins et al., 1997; Sisson et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2005; Zhou and Kalderon, 2010). In response to Smo signaling to the HSC, Ci accumulates in its full-length activator form and activates Hh target gene expression (Chen et al., 1999; Ohlmeyer and Kalderon, 1998; Robbins et al., 1997; Stegman et al., 2004; Wang and Holmgren, 2000). It is well documented that Smo association with Cos2 is a requisite step in HSC activation (Jia et al., 2003; Lum et al., 2003; Ogden et al., 2003; Ruel et al., 2003). We recently demonstrated that an additional mechanism by which Smo signals is to serve as a canonical GPCR, engaging the heterotrimeric G-protein Gαi (Ogden et al., 2008).

Like numerous GPCRs, Smo possesses spatially conserved cysteines in each of its extracellular (EC) loops (Fig. 1A and supplementary material Fig. S1A) (Karnik et al., 1988; Moro et al., 1999; Quirk et al., 1997; Rader et al., 2004). In the majority of GPCRs, loop cysteines facilitate disulfide bond formation between the EC1/Transmembrane domain 3 (TM3) junction and EC2 to stabilize a functional receptor conformation (Massotte and Kieffer, 2005). Alteration of this bond triggers dramatic effects on signaling by a range of well-characterized GPCRs, underscoring the importance of the EC loops and conserved loop cysteines (Cook et al., 1996; Moro et al., 1999). Despite vast interest in understanding how Smo signaling is regulated, specific examination for functional roles of its EC loops has not been reported.

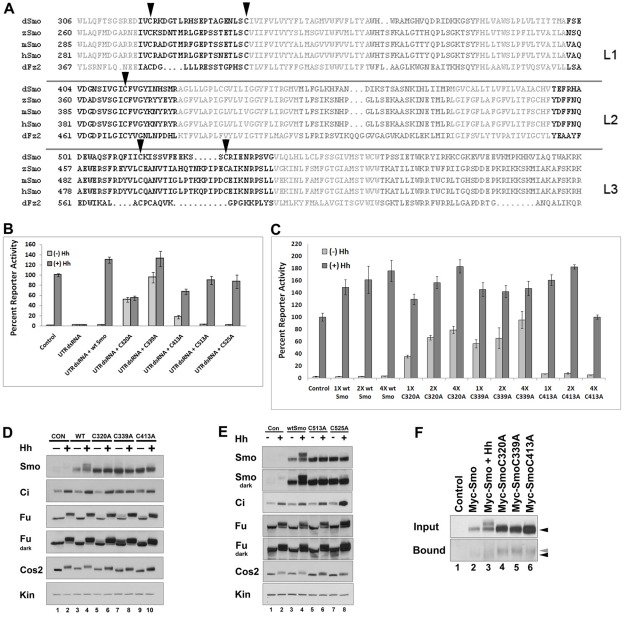

Fig. 1.

Conserved loop cysteines play a regulatory role in Smo signaling. (A) Alignment of Drosophila residues 306-596 against sequences of zebrafish, mouse, and human Smo proteins and Drosophila Frizzled2. Transmembrane residues are light gray, intracellular loops are dark gray and extracellular loops are black. Conserved loop 1 (L1) C320 and C339, loop 2 (L2) C413 and loop 3 (L3) C513 and C525 cysteines (Drosophila numbering) are indicated by arrowheads. Alignments were generated using StrapAlign (http://www.bioinformatics.org/strap/). (B) EC1 and EC2 cysteine mutants differentially rescue smo knockdown. Cl8 cells were treated with control or smo 5′UTR dsRNA and transfected with the indicated pAc-myc-smo expression vector. The ability of wild type or each of the Myc-Smo C to A mutants to rescue ptc-luciferase activity in presence of control vector (light gray bars) or pAc-hh (dark gray bars) is shown. The Hh-induced level of activity obtained in the presence of control dsRNA was set to 100%, and percent reporter activity relative to this value is shown. Activity levels are normalized to a pAc-renilla transfection control. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). (C) Loop 1 C to A mutants are dominant positive. Myc-Smo C to A mutant proteins were expressed in Cl8 cells with or without Hh, as indicated. Reporter activity was assessed as in B. In each case, 1X corresponds to 50 ng pAc-myc-smo. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (D) EC1 and EC2 cysteine mutants differentially activate downstream effectors. Lysates of Cl8 cells expressing wild-type or C to A mutant Smo proteins in the presence of pAc-hh (+) or empty vector (–) were examined by western blot. Short (Fu) and long (Fu dark) exposures are shown to visualize phosphorylation-induced mobility shifts (lanes 5 and 7). Samples are normalized to protein. Kinesin (Kin) serves as a loading control. (E) EC3 C to A mutants do not induce ligand-independent activation of downstream effectors. Lysates of Cl8 cells transfected with wild-type or C to A mutant pAc-myc-smo expression vectors with pAc-hh (+) or empty vector (–) were examined by western blot. Samples are normalized to protein. Kin serves as a loading control. (F) C to A mutants have free cysteines. Membrane fractions prepared from cells transfected with the indicated smo constructs were treated with maleimide-PEG11-biotin to label free cysteines. Biotinylated proteins were precipitated on NeutrAvidin agarose and surveyed by western blot against Smo (bottom panel). Wild-type and mutant Smo proteins demonstrate similar mobility before treatment (upper panel, black arrow). C to A mutants in affinity complexes migrate more slowly than wild-type Smo (bottom panel, gray arrow compared with black).

To test for functional roles of the Smo EC loops, we targeted each of the conserved loop cysteines, and examined effects of their loss on Smo-mediated pathway induction. Our results demonstrate that Smo EC loops play crucial roles in its regulation. We provide in vitro and in vivo evidence that cysteines in EC1 and EC2 are required to prevent Smo from inappropriately activating the Hh pathway. EC2 appears to play a pivotal role in regulating Smo signaling, as a single C to A mutation in EC2 compromises signaling (Nakano et al., 2004), whereas deletion of the central portion of EC2 renders it fully active. Taken together, our findings suggest that conserved EC cysteine residues engage in disulfide bonds that facilitate Smo loop conformations which prevent signaling in the absence of Hh but allow transition to an active state following ligand stimulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression vectors, transgenes and dsRNA preparation

pAc-myc-smo (Ogden et al., 2006) was mutated using a QuikChange II Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene), and mutations verified by sequencing. Mutant cDNA was amplified from pAc-myc-smo and cloned into pUASattB (Bischof et al., 2007) using NotI and KpnI restriction sites to generate pUAS-myc-smo. pCDNA-mouse(m)Smo was generated by excising Smo from pYX-ASC (Open Biosystems), and cloning into pCDNA3.1 using NotI and EcoRI restriction sites. C to A or deletion mutations were induced using QuikChange.

smo 5′UTR dsRNA template was amplified from BACR22C14 (DGRC), and ligated into pZero (Invitrogen) to generate pZero-smoUTR. T7 sites for dsRNA synthesis were introduced during amplification of smoUTR cDNA from pZero-smoUTR. dsRNA was generated as described (Ogden et al., 2008).

Lysate preparation and activity assays

Expression vectors and dsRNA were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For rescue experiments, ∼8×105 Cl8 cells were transfected with 500 ng smo 5′UTR dsRNA, 100 ng ptcΔ136-luc (Chen et al., 1999), 10 ng pAc-renilla (Ogden et al., 2006) and 50 ng of pAc-myc-smo. DNA and RNA content were normalized with pAc5.1A and/or control dsRNA. For dominant activity assays, cells were transfected with 100 ng pAc-hh and increasing amounts of pAc-myc-smo (1X=50 ng). Cells were lysed ∼48 hours post-transfection and luciferase activity measured using Dual Luciferase (Promega). Assays were performed two or three times in duplicate, and all data pooled. For mammalian reporter assays, ∼75,000 NIH3T3 cells were transfected with 100 ng 8XGlibs-luciferase (Sasaki et al., 1997), 100 ng pRL-TK (Promega), 100 ng wild-type or mutant pCDNA-mSmo and 200 ng pCDNA-Shh or empty vector. Reporter activity was measured ∼48 hours post-transfection. Assays were performed twice in triplicate, and all data pooled. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

For biochemical analysis, 8×106 Cl8 cells were transfected with 5 μg of pAc-myc-smo and 3 μg of pAc-hh. DNA content was normalized using pAc5.1A. Forty-eight hours post-transfection cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 50 mM NaF, 0.5 mM DTT, and 1X PIC (Roche), pH 8.0), and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2000 g. Samples were analyzed by western blot with the following antibodies: anti-Myc (Roche), anti-Smo (Ogden et al., 2006), anti-Fused (Ascano et al., 2002), anti-Cos2 (Stegman et al., 2000), anti-Ci anti-Ptc (gifts from T. Kornberg, UCSF, USA) and anti-Kinesin (Cytoskeleton).

For λphosphatase analysis, lysates were prepared as above, diluted 30% with buffer (0.1% Brij35, 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 1× NEB PMP), then treated with 800U of λphosphatase for 30 minutes at 30°C. Reactions were stopped by adding SDS sample buffer containing 200 mM DTT.

For maleamide labeling, cells were lysed hypotonically and membrane pellets prepared from ∼1 mg total protein (Ogden et al., 2003). Membranes were resuspended in 0.1% NP-40 Buffer containing 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2. Samples were pre-cleared against NeutrAvidin agarose for 30 minutes at 4°C, then incubated with 1.25 mM maleimide-PEG11-biotin (Thermo) for 30 minutes on ice. Maleimide-labeled proteins were collected on NeutrAvidin agarose, washed with 0.1% NP-40 Lysis Buffer and eluted in 5X SDS Buffer (10% SDS, 20% glycerol, 200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.05% Bromophenol Blue, 1 mM DTT, 1% β-mercaptoethanol). Samples were analyzed by western blot using anti-Smo.

Fly crosses and transgenes

Transgenes were targeted to landing site 3L-68E using the phiC31 system (Bischof et al., 2007). UAS-myc-smo transgenes were expressed with 69B-, MS1096- and/or C765-Gal4. All crosses were performed at 25°C twice at minimum, and multiple flies were analyzed.

Wings were dissected from male flies, and mounted on glass slides using DPX mounting media. Wing imaginal discs were dissected from third instar larvae and fixed, stained and mounted as described (Ogden et al., 2006). To generate FLP-out clones, ywhsflp,actin[FRT-CD2]GAL4; UAS-myc-smo first instar larvae were heat-shocked for 1 hour at 37°C. Imaginal discs were immunostained using Ci, Ptc, Smo and β-gal (Promega) primary antibodies and appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Representative discs are shown.

Embryos were collected for 3 hours and aged for ∼15 hours. Embryos were dechorionated in 50% bleach for 2 minutes, mounted using Hoyers:lactic acid (50:50), and fixed for ∼3 hours at 55°C. Abdominal segments 3-4 were examined.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

Cl8 or S2 cells (∼6×106) were transfected as described above. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were replated on chamber slides and immunostained as described (Ogden et al., 2006). Alexa 633 phalloidin (Invitrogen) was used to mark the plasma membrane and Cal-GFP-KDEL marked the ER (Casso et al., 2005).

For mammalian Smo localization analysis, ∼ 75,000 NIH 3T3 cells were plated on Permanox-coated chamber slides and transfected with 1 μg pCDNA-mSmo or pCDNA-mSmoC318A in the absence or presence of pCDNA-Shh using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours post-transfection cells were immunostained using anti-mSmo (E5, Santa Cruz), anti-GRP94 ER (Shen et al., 2002) and anti-γ tubulin (Sigma). To examine primary cilia, cells were fixed, stained and imaged as previously described (Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011).

To quantify Myc-Smo localization in Cl8 cells, seven fields of cells were imaged over two independent experiments. Percent colocalization with the ER marker was calculated. Error indicates s.e.m.

Confocal images were collected using a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO Meta Microscope. Wings were imaged on a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam ICc3 camera, and embryos on a Nikon E800 with a Nikon DMX1200c camera. Images were prepared using Photoshop CS4.

RESULTS

Amino acids localizing to the EC loops were predicted using http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/, which identified residues consistent with published extracellular and transmembrane domain predictions (Fig. 1A and supplementary material Fig. S1A) (Alcedo et al., 1996). Residue C339, predicted to localize to the EC1/TM3 junction (hereafter referred to as TM3) was also included in our analyses, as this spatially conserved cysteine forms a disulfide bond with an EC2 cysteine in the vast majority of characterized GPCRs (Karnik et al., 1988; Moro et al., 1999; Rader et al., 2004).

EC1 and EC2 cysteine mutants induce ectopic Hh pathway activation in vitro

Each EC loop cysteine was individually mutated to alanine. We tested the ability of EC loop C to A mutants to rescue Hh-dependent reporter gene activation following knockdown of endogenous smo (Fig. 1B). Transfection of smo 5′UTR dsRNA into Clone 8 (Cl8) cells eliminated activation of the ptcΔ-136-luciferase (ptc-luciferase) reporter construct (Chen et al., 1999). As control, we co-transfected wild-type myc-smo with UTR dsRNA, and observed rescue of Hh-dependent reporter induction to near wild-type levels. Whereas mutation of EC3 cysteine residues (C513A and C525A) did not alter rescue of reporter gene activity, mutation of conserved cysteine residues in EC1 (C320A), TM3 (C339A) and EC2 (C413A) did (Fig. 1B). Mutation of these residues triggered increased baseline activity, ranging from ∼20% (C413A) to ∼100% (C339A) of the control Hh response. Although the EC1 and EC2 substitutions were able to induce ectopic signaling in the absence of Hh, they demonstrated attenuated Hh-induced activity (Fig. 1B), suggesting that alteration of these residues shifts Smo toward a low- to intermediate-level signaling conformation. Myc-SmoC339A was nearly fully active in both the absence and presence of Hh, suggesting that this mutation triggers a highly active conformation.

To determine whether EC1, TM3 and EC2 loop mutants possessed dominant activity in the presence of endogenous Smo, we tested their ability to alter reporter gene expression in a wild-type smo background (Fig. 1C). Whereas all constructs enhanced Hh-induced reporter gene activation, they demonstrated significant differences in their effects on baseline signaling. Consistent with the previously characterized post-translational regulation of Smo (Alcedo et al., 2000; Denef et al., 2000), increasing amounts of wild-type Myc-Smo did not alter baseline reporter activity. However, both C320A and C339A mutants increased baseline activity in a dose-dependent manner, reaching an activity level near to that of the control Hh response (Fig. 1C). By contrast, C413A increased baseline reporter activity only modestly, and did so in a non-dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 1C).

In response to Hh, Smo is stabilized and phosphorylated, Fu and Cos2 are phosphorylated and Ci is stabilized in its full-length form to activate target genes, including ptc and decapentaplegic (dpp) (Aza-Blanc et al., 1997; Denef et al., 2000; Robbins et al., 1997; Sisson et al., 1997; Therond et al., 1996). To determine whether EC1, TM3 and EC2 mutants could induce these Hh responses in endogenous signaling components in the absence of ligand, we performed western blot analysis on lysates prepared from Cl8 cells expressing wild-type or mutant myc-smo constructs (Fig. 1D and supplementary material Fig. S1B,C). Fu phosphorylation was not significantly altered by expression of wild-type or C413A Myc-Smo proteins. However, EC1 and TM3 cysteine mutants, C320A and C339A, triggered some Hh-independent phosphorylation (Fig. 1D and supplementary material Fig. S1B,C). Whereas Myc-SmoC320A did not have a significant effect on Ci or Ptc (Fig. 1D and supplementary material Fig. S1C), C339A induced ligand-independent stabilization of Ci and induction of Ptc protein to a level similar to that of Hh (Fig. 1D and supplementary material Fig. S1C). This is consistent with the near full induction of reporter gene activity by C339A in both the absence and presence of Hh (Fig. 1B,C). Myc-SmoC413A induced modest ligand-independent Ci stabilization (Fig. 1D, lane 9), but was unable to induce endogenous Ptc (supplementary material Fig. S1C). The modest effects on Fu and Ci, and lack of induction of Ptc by C320A and C413A, are more consistent with intermediate pathway activity, as suggested by the less robust reporter gene activity induced by these mutants following knockdown of endogenous smo (Fig. 1B).

Although each of the Smo EC loop mutants demonstrated increased stability compared with wild-type Myc-Smo, we did not observe extensive phosphorylation-induced mobility shifts of loop mutants in either the absence or presence of Hh (Fig. 1D, lane 4 compared with 5-10, Smo). To confirm that the mobility shift of wild-type Myc-Smo was the result of Hh-induced phosphorylation, and to determine whether C to A mutants had any detectible phosphorylation, we treated lysates with λphosphatase, and examined for changes in wild-type and mutant Smo protein mobility (supplementary material Fig. S1D). Whereas Hh-stimulated Myc-Smo demonstrated a significant downward shift following λphosphatase treatment (lanes 3, 4), non-Hh-stimulated Myc-Smo and each of the C to A mutants shifted down only modestly (lanes 1, 2 and 5-16), suggesting an attenuated level of phosphorylation.

To determine whether activating C to A mutants could signal in the absence of known Smo phosphorylation sites, we mutated previously characterized PKA, CK1, GSK3β and GPRK2 sites (Apionishev et al., 2005; Jia et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2007) to alanine, alone and in combination with the activating C339A mutation, and tested the ability of compound mutants to rescue reporter gene activity in a smo knockdown background (supplementary material Fig. S1E and data not shown). Ablation of PKA and CK1 sites compromised the ability of both wild-type and C339A Smo proteins to rescue reporter activity, indicating a requirement for these sites (data not shown). Conversely, SmoC339A rescued the Hh response, and elevated baseline signaling activity in the presence of either GSK3β or GPRK2 phosphorylation site mutation (supplementary material Fig. S1E). Further, the C339A mutation was able to confer ectopic activity to the GPRK2/GSK3β site compound mutant, albeit at a lower level. Taken together, these results suggest that GSK3β and GPRK2 phosphorylation sites are not required for induction of ectopic signaling by the C339A mutation. We speculate that the lack of mobility shift of EC C to A mutants could be owing to reduced higher-order phosphorylation by GSK3β and/or GPRK2.

We tested for effects on Hh pathway components by the EC3 mutants C513A and C525A, both of which demonstrated wild-type-like activity in reporter assays (Fig. 1B). Similar to the activating EC1 and EC2 mutant proteins, both EC3 mutants appeared more stable than wild-type Myc-Smo (Fig. 1E, compare lanes 5-8 with 3 and 4). However, they did not induce ectopic Fu or Cos2 phosphorylation or Ci stabilization (Fig. 1E), suggesting that increased signaling by EC1, TM3 and EC2 mutants was not the result of their increased stability. Hh-induced mobility shifts of Myc-SmoC513A and Myc-SmoC525A proteins were detectable, although modest compared with that of wild-type Myc-Smo (Fig. 1E, compare lanes 6 and 8 with 4, Smo dark exposure).

To determine whether the altered signaling activity of EC1 and TM3 mutants C320A and C339A and/or EC2 mutant C413A results from disruption of a disulfide bridge, we expressed wild-type and each of these mutants in Cl8 cells, and labeled free cysteines using maleimide-PEG11-biotin (Fig. 1F). Cellular membrane fractions were treated with maleimide-biotin, and biotinylated proteins collected on NeutrAvidin agarose. Modest amounts of wild-type Myc-Smo could be detected in NeutrAvidin precipitates (Fig. 1F, bottom panel), indicative of free cysteines in wild-type Smo capable of binding biotinylated maleimide. Higher levels of the EC1, TM3 and EC2 C to A mutants were present in biotin affinity precipitates, suggesting an increased level of biotinylated maleimide label (compare lanes 4-6 with 2 and 3). This is consistent with a larger number of free cysteines, suggesting that C to A mutation of any of these residues results in disruption of a disulfide bond. Furthermore, whereas wild-type and C to A mutant Myc-Smo demonstrated similar electrophoretic mobilities before maleimide-biotin labeling (top panel, black arrowhead), affinity-precipitated C to A mutant proteins consistently demonstrated slower mobilities compared with that of precipitated wild-type Smo (bottom panel gray arrowhead compared with black arrowhead). These results are consistent with higher-order maleimide-PEG11-biotin linkage to a larger number of free cysteines (Thermo technical support personal communication). Taken together, these results suggest that C320, C339 and C413 engage in functionally relevant disulfide bonds.

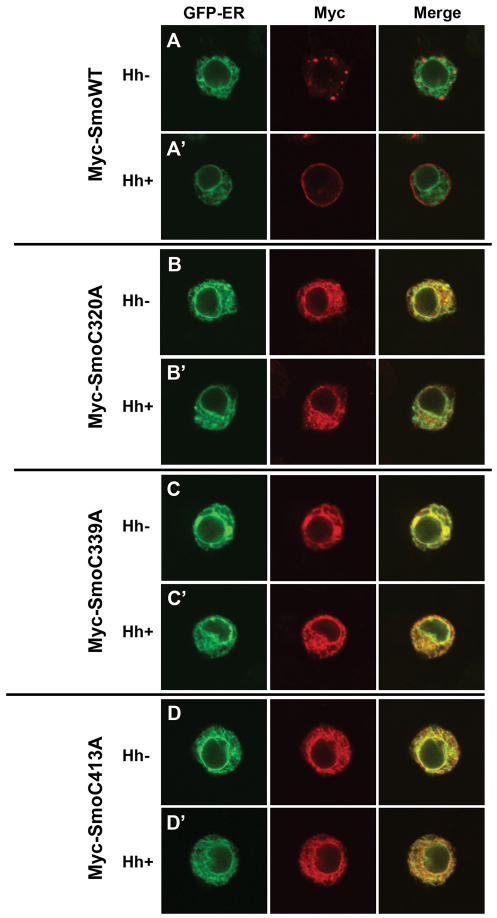

EC1 and EC2 cysteine mutants demonstrate altered subcellular localization

Smo subcellular localization is tightly regulated, and correlates with its signaling activity (Denef et al., 2000; Rohatgi et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2003). In the absence of Hh, Smo localizes to intracellular vesicles including recycling endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 2A, and supplementary material Fig. S2A) (Incardona et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2003). Hh triggers Smo relocalization to the PM (Fig. 2A′, and supplementary material Fig. S2A′) (Denef et al., 2000). Because relocalization from punctate structures to the PM correlates with active signaling, we wanted to determine whether activating loop mutants demonstrated a non-punctate localization in the absence of Hh. Wild-type and EC loop mutant Smo proteins were expressed in Cl8 (Fig. 2) or Schneider 2 (S2) cells (supplementary material Fig. S2), and examined for localization in the absence and presence of Hh. Given the high level activity of the C320A and C339A Smo mutants, we predicted that they would localize to the PM. On the contrary, both highly active mutants, as well as the moderately active EC2 mutant C413A, localized exclusively to the ER (supplementary material Table 1 and Fig. 2B-D compared with 2A, supplementary material Fig. S2B compared with S2A and data not shown). This localization did not change in response to Hh, suggesting that, like the oncogenic SMO-A1 mutant, active C to A mutants are capable of signaling from the ER, in a Hh-independent manner (Chen et al., 2002; Taipale et al., 2000).

Fig. 2.

Smo EC1 and EC2 mutants demonstrate altered subcellular localization. (A-D) Cl8 cells expressing the indicated Smo constructs in the presence of empty vector (Hh–) or pAc-hh (Hh+) were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence. Smo was detected with anti-Myc (red). Calreticulin-GFP-KDEL (green) marks the ER.

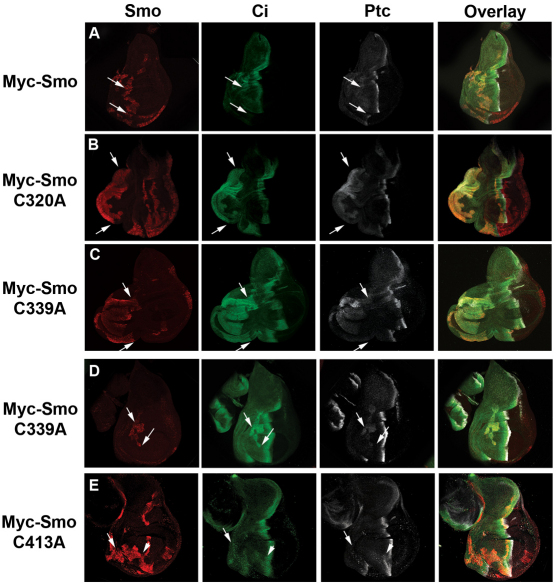

Activating EC1 mutants induce Hh gain-of-function phenotypes in vivo

To determine whether the level of Hh pathway activation induced by EC1 and EC2 mutants in vitro could trigger Hh gain-of-function phenotypes in vivo, we generated transgenic Drosophila to express wild-type and C to A mutant Myc-Smo constructs under control of the UAS/Gal4 system. In order to obtain comparable expression of our smo transgenes in vivo, we utilized the phiC31 system to target all constructs to the same genetic location (Bischof et al., 2007). Smo constructs were expressed in wing discs in FLP-out clones (Fig. 3 and supplementary material Fig. S3A) or under control of C765- or apterous (ap)-Gal4 (supplementary material Fig. S3B-G). Wing discs were analyzed by western blot for Smo stability and indirect immunofluorescence for effects on Ci, ptc and dpp-lacZ (Fig. 3 and supplementary material Fig. S3B-G). Myc-Smo proteins demonstrated similar stabilities, with the exception of wild-type Myc-Smo and Myc-SmoC413A, both of which were consistently observed at lower levels in vivo (supplementary material Fig. S3B). Neither clonal nor ap-Gal4-induced expression of wild-type or C413A myc-smo constructs was able to induce significant stabilization of full-length Ci or ectopic ptc or dpp-lacZ expression (Fig. 3A,E and supplementary material Fig. S3D,G). Conversely, EC1 and TM3 mutants Myc-SmoC320A and C339A induced robust ectopic pathway activity. FLP-out clones expressing either of these mutants triggered Ci stabilization and ectopic ptc expression (Fig. 3B-D), with FLP-out clones localized to the far anterior of the wing disc inducing wing pouch and wing blade duplications (Fig. 3B,C, arrows and supplementary material Fig. S3A). Further, expression of either C320A or C339A mutants under control of ap-Gal4 induced disc over-growth and ectopic dpp-lacZ induction into the far anterior compartment (supplementary material Fig. S3E,F). Taken together, these results suggest that C320A and C339A mutants are capable of a high level of Hh-independent signaling in vivo.

Fig. 3.

EC1 and EC2 mutants alter Hh signaling in vivo. (A-E) myc-smo constructs were expressed in FLP-out clones, as indicated. Wing imaginal discs from late third instar larvae were immunostained for Ci (green), Ptc (white) or Myc-Smo (red). All images were collected at equal gains. All discs are oriented anterior to the left, posterior to the right, dorsal up and ventral down. Clones are indicated by arrows.

To determine phenotypic effects induced by EC mutants, we examined cuticle patterning of the embryonic ectoderm and wings of adult flies (Fig. 4 and supplementary material Fig. S4). We expressed UAS-myc-smo transgenes in the embryo under control of 69B-Gal4 and in the developing wing under control of C765- or MS1096-Gal4. To confirm that the presence of an amino-terminal Myc tag would not alter Smo activity, we expressed both tagged and untagged wild-type UAS-smo (Fig. 4B and supplementary material Fig. S4A,B compared with Fig. 4A, control). The Myc tag did not affect Smo signaling; both constructs resulted in a similar Hh gain-of-function phenotype, triggering the formation of ectopic LV2-3 cross veins (supplementary material Fig. S4A,B, arrows). Myc-Smo did not alter cuticle patterning (supplementary material Fig. S4G). Consistent with its inability to ectopically induce Ci, ptc or dpp-lacZ, myc-SmoC413A under control of either C765- or MS1096-Gal4 triggered only modest ectopic vein formation anterior to LV3, and did not alter cuticle patterning (Fig. 4E and supplementary material Fig. S4D, arrows, and S4J). Conversely, both myc-smoC320A and myc-smoC339A induced more pronounced ectopic venation anterior to LV3, overgrowth of the far anterior of the wing blade, and altered denticle patterning in the embryonic cuticle (Fig. 4C,D, supplementary material Fig. S4C, arrow, and S4H,I). Although SmoC320A occasionally duplicated denticle type 3 (supplementary material Fig. S4H, arrowheads), it was unable to convert denticle fate across the denticle band. myc-smoC339A expression triggered conversion of multiple denticles to type 2, in a manner similar to, although not as dramatic as, that of UAS-hh (supplementary material Fig. S4I, brackets, compared to K and L). The EC3 mutants, C513A and C525A, both of which functioned similar to wild-type Smo in vitro, did not induce Hh gain-of-function phenotypes when expressed in the wing (supplementary material Fig. S4E,F). Both of these mutants demonstrated an in vivo level of stability similar to that of the active C320A and C339A Smo mutants (supplementary material Fig. S3B), suggesting that high-level in vivo signaling by C320A and C339A is not due to increased stability.

Fig. 4.

Smo EC mutants induce wing phenotypes. (A-E) myc-smo constructs were expressed under control of C765-Gal4 at 25°C, as indicated. Wings from adult male flies were mounted on glass slides and imaged under equal magnification. For each cross, multiple flies were analyzed. Representative wings are shown. Driver wing serves as control (A).

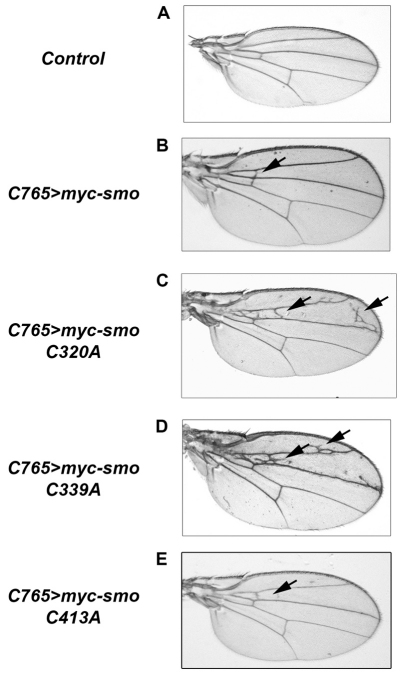

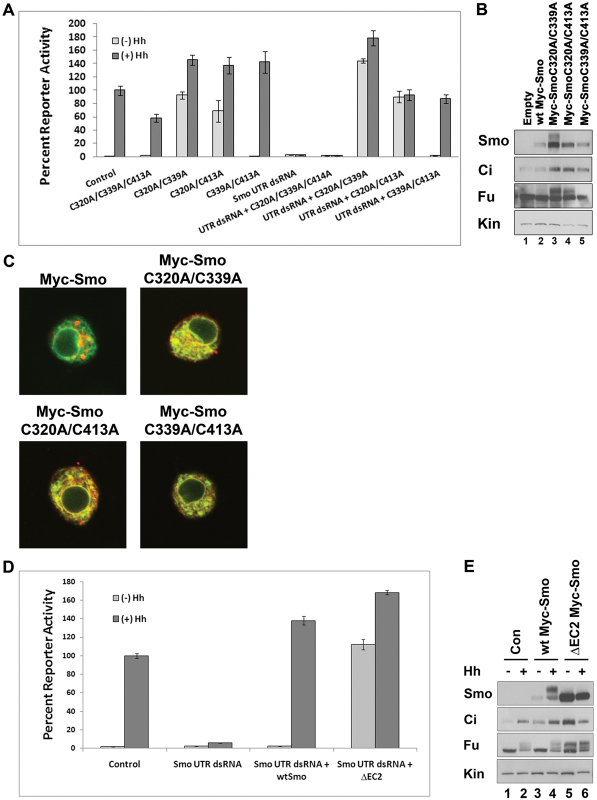

Compound loop cysteine mutants reveal an important role for EC2

Cysteines localized to TM3 in the majority of GPCRs engage in disulfide bonds with cysteines in EC2 (Klco et al., 2005; Moro et al., 1999). In an attempt to determine whether this bond might exist in Smo, and whether its loss was responsible for the observed C to A mutant phenotypes, we mutated loop cysteines in pairs, and all three in combination (Fig. 5). We transfected Smo double or triple mutant expression vectors into Cl8 cells, and examined their ability to activate the ptc-luciferase reporter construct in wild-type and smo knockdown backgrounds. The Myc-SmoC320A/C339A/C413A mutant, predicted to break at least two disulfide bonds, did not rescue knockdown of endogenous smo and appeared to function as a weak dominant-negative protein in a wild-type smo background, attenuating the Hh response by ∼40% (Fig. 5A). Myc-SmoC320A/C339A and Myc-SmoC320A/C413A double mutants, both of which would be predicted to break the TM3-EC2 disulfide bond, were able to activate baseline reporter gene expression to a level similar to, or greater than, that of the control Hh response (Fig. 5A). By contrast, the C339A/C413A double mutant did not induce ectopic activation of ptc-luciferase in wild-type or smo knockdown backgrounds, but was able to rescue the Hh response in cells treated with smo 5′UTR dsRNA (Fig. 5A), suggesting that this double mutant behaves similarly to wild-type Smo.

Fig. 5.

C to A compound mutants reveal a pivotal role for EC2. (A) Activating double C to A Smo mutants induce robust reporter gene activation. myc-smo C to A double mutant constructs were expressed in wild-type or smo knockdown backgrounds (UTR dsRNA), as indicated, and assessed for their ability to activate the ptc-luciferase reporter construct. Fifty ng of the indicated pAc-myc-smo vector was used in dsRNA rescue transfections, while 100 ng of the indicated pAc-myc-smo vectors were used to test for dominant activity in the wild-type smo background. Activity is shown as percent activity relative to the control Hh response, set to 100%. All values are normalized to a pAc-renilla transfection control. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (B) Activating double C to A Smo mutants signal to downstream effectors. Lysates from Cl8 cells transfected with the indicated Myc-Smo double mutant vectors were examined by western blot. Anti-Myc was used to blot for Myc-Smo protein. Samples are normalized to protein concentration. Kin serves as loading control. (C) Activating C to A double mutants have altered subcellular localization. The indicated loop double C to A mutant constructs were transfected into Cl8 cells in the absence of Hh and examined for subcellular localization by indirect immunofluorescence. Smo (anti-Myc) is in red, Calreticulin-GFP-KDEL is green. (D) ΔEC2 induces robust reporter gene activity. Cl8 cells were treated with control or smo 5′UTR dsRNA and transfected with the indicated pAc-myc-smo expression vector. Activity is shown as percent activity relative to the control Hh response. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (E) ΔEC2 signals to downstream effectors. Lysates from Cl8 cells transfected with the indicated pAc-myc-smo constructs were examined by western blot. Anti-Myc was used to blot for Myc-Smo. Samples are normalized to protein concentration. Kin serves as loading control.

To determine whether the activating double mutants induced reporter expression by signaling through Fu and Ci, we expressed wild-type or double mutant constructs in Cl8 cells, and examined lysates for Myc-Smo expression and ectopic activation of downstream components (Fig. 5B). Whereas Myc-SmoC320A/C339A and C320A/C413A proteins were more stable than wild-type Myc-Smo, the C339A/C413A mutant expressed similarly to wild-type Myc-Smo, and did not alter Ci stabilization or Fu phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, lane 5 compared with lanes 1 and 2). The SmoC320A/C339A double mutant existed in a partially phosphorylated state in the absence of Hh, suggesting a robust level of activation (Fig. 5B, lane 3). Indeed, this mutant triggered significant phosphorylation of Fu and stabilization of Ci in the absence of Hh (Fig. 5B, lane 3). Although the Myc-SmoC320A/C413A double mutant did not appear to be hyper phosphorylated, it was able to trigger Ci stabilization and Fu phosphorylation to a level near to that of the C320A/C339A double mutant (Fig. 5B, lane 4).

As with the single C to A mutants, each of the compound C to A mutant Myc-Smo proteins were retained in the ER (Fig. 5C). We did observe modest PM localization of the highly active C320A/C339A double mutant (Fig. 5C, upper right panel), potentially explaining why it is the only activating mutant to demonstrate higher-order phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, lane 3) (Chen et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2010; Molnar et al., 2007).

Given our prediction that TM3 residue C339 is engaged in a disulfide bond with EC2 residue C413, we were surprised to find that the two mutants possessed significantly different activities. To determine whether an activating mutant could be generated by targeting EC2, we deleted conserved amino acids in EC2 surrounding C413 (G411 to Y417), and tested the ability of this ΔEC2 construct to rescue reporter gene activation in the smo knockdown background. Similar to what was observed with the C339A mutant (Fig. 1B), Myc-SmoΔEC2 was able to induce a level of Hh-independent reporter activation equal to that of the control Hh response (Fig. 5D). Further, expression of this mutant in a wild-type background induced robust Hh-independent Fu phosphorylation and Ci stabilization (Fig. 5E), indicative of high-level signaling. These results suggest that conformation of EC2 is crucial for Smo regulation. As such, we hypothesized that, if C339 and C413 do form a bond to stabilize EC2, the differing activities of C339A and C413A might result from activity of the remaining free cysteine.

Because C413 is predicted to localize to the central region of a flexible loop, we speculated that it might form a disulfide bond with an inappropriate cysteine upon mutation of its bond partner C339. To test this hypothesis, we scanned for cysteines that, like C339, are predicted to localize to the extracellular face of a TM domain. We identified two residues, C432 (TM5) and C478 (TM6), as potential ‘rogue’ bond partners for free C413 (supplementary material Fig. S5A). We mutated each of these cysteines alone, and in the C339A background. Myc-SmoC432A and Myc-SmoC478A rescued reporter activity in the smo knockdown background to a level similar to that of wild-type Myc-Smo (supplementary material Fig. S5B), suggesting that they are not normally engaged in requisite disulfide bonds. Whereas C432A mutation in the C339A background did not alter signaling by C339A, mutation of C478A in the C339A background did. The C339A/C478A mutant demonstrated a level of activity more similar to C413A than to C339A (supplementary material Fig. S5C compared with Fig. 1B). As such, we speculate that C339 and C413 are normally engaged in a disulfide bond, and that the formation of an inappropriate bond between free C413 and C478 triggers a conformation shift that facilitates high-level signaling following C339A mutation.

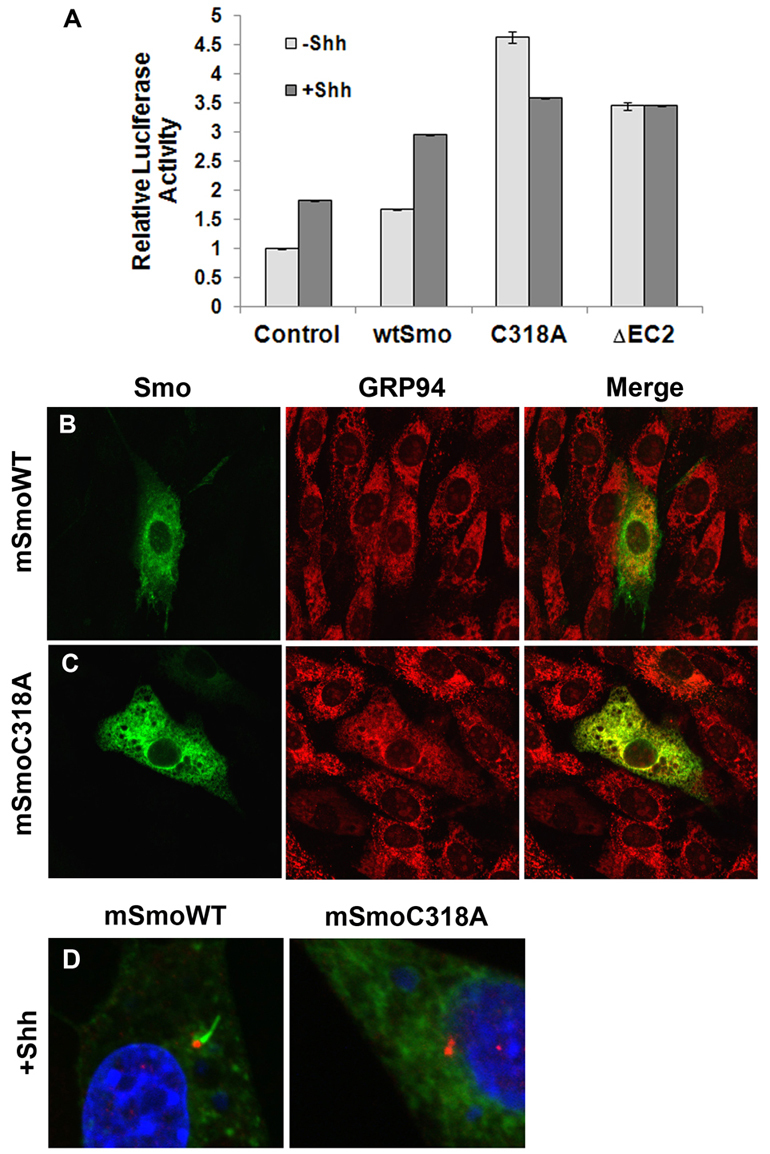

Evidence for a TM3-EC2 disulfide bond in mammalian Smo

To determine whether the TM3-EC2 bond might play an important role in mammalian Smo function, we generated equivalent mutations of the highly active C339A and ΔEC2 Smo mutants in a murine Smo expression vector (pCDNA-mSmo), and examined their activity in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 6). Whereas expression of wild type Smo triggered a modest elevation of baseline and Shh-stimulated reporter gene activity, expression of C318A (C339A equivalent) or ΔEC2 mSmo proteins elevated baseline signaling to a level higher than that of both control and wtSmo Shh responses (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

The TM3-EC2 bond is important for mammalian Smo. (A) TM3-EC2 mutants are constitutively active. NIH3T3 cells were transfected with the indicated pCDNA-mSmo construct in the presence of pCDNA-Shh or empty vector. Relative activation of 8XGlibs-luc, normalized to pRL-TK is shown. Assays were repeated twice in triplicate and all data pooled. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (B-D) The TM3 C to A mutant is retained in the ER. NIH3T3 cells were transfected with the indicated pCDNA-mSmo expression vector in the absence (B-C) or presence (D) of pCDNA-Shh, and examined for Smo subcellular localization by indirect immunofluorescence. (B-C) Smo is green, GRP94 (ER marker) is red. (D) Smo is green, γ-tubulin (red) marks the base of the primary cilium and DAPI (blue) marks the nucleus. Whereas wild-type Smo enters the primary cilium in the presence of Shh, the C318A Smo mutant does not.

We next examined subcellular localization of the C318A mutant. Whereas wild-type mSmo localized primarily to non-ER structures, C318A was confined entirely to the ER, demonstrating complete co-localization with the ER marker GRP94 [Fig. 6C compared with 6B (Shen et al., 2002)]. Wild-type Smo relocalized to the primary cilium in response to Shh (Fig. 6D). SmoC318A did not relocalize to the primary cilium following Shh stimulation (Fig. 6D), suggesting that, as with mutant Drosophila Smo proteins, mammalian Smo mutants affecting the canonical TM3-EC2 disulfide bridge are highly active, despite being retained in the ER.

DISCUSSION

The results presented demonstrate that conserved cysteine residues in the EC loops of Smo are necessary for proper regulation of Smo signaling. We propose that these cysteines engage in disulfide bonds that stabilize EC loop conformations to prevent signaling in the absence of Hh but allow Smo to transition to a fully active state in response to Hh.

Evidence for a disulfide bond stabilizing Smo EC2

A functional role for EC loop cysteines in GPCR regulation was identified through biochemical and structural studies on the prototypical GPCR rhodopsin, which revealed a TM3-EC2 disulfide bridge to be essential for regulated receptor activity (Karnik et al., 1988; Klco et al., 2005; Palczewski et al., 2000; Rader et al., 2004). Accordingly, subsequent studies on additional GPCR family members support the presence and importance of this bond (Cherezov et al., 2007; Chien et al. 2010; Cook et al., 1996; Hoffmann et al., 1999; Moro et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2010). C5a receptor mutagenesis revealed TM3 and EC2 cysteines to be necessary for stabilizing its inactive conformation (Klco et al., 2005). Based upon this work, it was suggested that a general theme in GPCR biology is that EC2 is restrained by the TM3-EC2 disulfide bridge to drive a closed conformation (Klco et al., 2005; Massotte and Kieffer, 2005). Loss of this bond is hypothesized to trigger a relaxed, open conformation capable of ligand-independent signaling (Massotte and Kieffer, 2005).

Mutation of Smo TM3 residue C339 or deletion of the central portion of EC2 induced full reporter gene activation, Fu phosphorylation and Ci stabilization in an Hh-independent manner. Further, expression of C339A in vivo induced Hh gain-of-function phenotypes, indicating a robust level of signaling. Given the similarly high signaling by both C339A and ΔEC2 Smo mutants, we hypothesize that the canonical GPCR TM3-EC2 bond exists between TM3 reside C339 and EC2 residue C413 of Smo. Why then, does the C339A Smo mutant induce effects on pathway activity that are distinct from those of C413A? We speculate that activities induced by loss of this bond may be influenced by behavior of the newly free cysteine, probably through engaging in an inappropriate disulfide bond that alters loop conformation. As such, we hypothesize that enhanced activity of SmoC339A results from C413 forming a disulfide bridge with an inappropriate cysteine that triggers an active EC2 conformation.

We favor C478 as the inappropriate C413 bond partner because: (1) Mutation of C478 in the wild-type background does not alter Smo signaling, suggesting that it is not engaged in an essential disulfide bridge; (2) mutation of C478 in the C339A background converts C339A to an activity level similar to that of C413A; (3) C339 and C478 are approximately equidistant from C413; (4) C413 binding to C478 would probably alter EC2 conformation, potentially mimicking the active state. As such, reversion of C339A/C413A back to a wild-type level of activity is explained by loss of this new, inappropriate bond. These results underscore the importance of EC2 in regulating Smo signaling, suggesting that its conformation is crucial for maintaining Smo in an inactive conformation in the absence of Hh.

In contrast to the high-level activity of C339A and ΔEC2 Smo mutants, the EC2 mutant C413A facilitated only partial rescue of reporter gene activity in the smo knockdown background, and modest effects on Ci when expressed in a wild-type background in vitro. Accordingly, smo4D1, a C to S mutation of C413, was previously classified as a weak loss of function allele (Nakano et al., 2004). When the UAS-smoC413A transgene was expressed in vivo, it triggered only modest phenotypes in the wing, and did not affect cell fate in the embryonic ectoderm. The decreased activity of SmoC413A compared with that observed following mutation of its suspected bond partner C339 might be explained by the predicted localization of C339 to the amino-terminus of TM3. This inflexible region may prevent C339 from scavenging a new disulfide bond partner following C413A mutation, thereby preventing an activating conformational shift. However, mutation of C413 does have a functional consequence. Given its inability to fully rescue smo knockdown in vitro or to induce Hh phenotypes in vivo, we hypothesize that C413A mutation triggers an EC2 conformation that is incapable of becoming fully activated by Hh. This, taken together with the activating effects of ΔEC2 mutation, highlights the importance of EC2 in regulating the activation state of Smo.

Evidence for a second disulfide bond stabilizing Smo EC1

Based upon the phenotypes of SmoC320A we propose that EC1 residue C320 is engaged in an additional disulfide bond that assists in stabilizing the inactive conformation of Smo. This conclusion is based upon the ability of C320A to induce moderate pathway activity in vitro and to induce Hh gain-of-function wing phenotypes when expressed in vivo. The presence of two disulfide bonds, one involving C320 and one involving C339, is further supported by the additive effect of the C320A/C339A double mutant, which demonstrated significantly higher ligand-independent signaling than either single mutant. Further, the C320A/C339A/C413A triple mutant triggered a complete loss of function, potentially due to an altered conformation resulting from loss of multiple stabilizing disulfide bonds.

Despite its higher baseline activity, Smo C320A was unable to fully rescue Hh-induced reporter activity in the smo knockdown background. This suggests that, similar to SmoC413A, SmoC320A is unable to transition to a fully active state. As such, higher-level reporter gene induction and wing phenotypes triggered by C320A in a wild-type background probably result from SmoC320A engaging endogenous Smo. Taken together, these results support that, like EC2, EC1 plays an important role in regulating Smo, probably through a conformation dependent upon a disulfide bond involving C320. Although our study does not reveal a bond partner for C320, we hypothesize that it may interact with one of the numerous cysteines in the amino-terminal cysteine-rich domain (CRD), as the CRD has been proposed to contribute to both active and inactive states of Smo (Aanstad et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Given the significant impact of mutation of cysteines located in the EC loops of Drosophila and murine Smo proteins, our results support the idea that EC1 and EC2 play crucial roles in Smo regulation. These findings suggest that cysteine residues localized within EC1 and EC2 are engaged in disulfide bonds that serve to stabilize the off state of Smo in absence of Hh and to allow for transition to the active state in the presence of Hh. Although conformation of disulfide bond pairs awaits formal structural studies, cell biological and genetic analyses support that the EC loops of Smo are indispensable for its function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Hendershot, J. Zheng and Y. G. Han for thoughtful discussion, and Y. Ahmed, P. Mead and J. Opferman for comments on the manuscript. We thank T. Kornberg, D. Casso, L. Hendershot and D. Robbins for antibodies. Drosophila smo genomic DNA was obtained from the DGRC and mouse Smo from Open Biosystems. Gal4 driver stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. Best Gene performed embryo injections. We are grateful to the SJCRH Hartwell Center and Cell and Tissue Imaging Center for expert assistance.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the March of Dimes [5-FY10-6 to S.K.O.]; by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Core Support grant [5P30CA021765-32 to St Jude Children’s Research Hospital]; by an United Negro College Fund (UNCF)-Merck Fellowship to C.E.C.; and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.075614/-/DC1

References

- Aanstad P., Santos N., Corbit K. C., Scherz P. J., Trinh le A., Salvenmoser W., Huisken J., Reiter J. F., Stainier D. Y. (2009). The extracellular domain of Smoothened regulates ciliary localization and is required for high-level Hh signaling. Curr. Biol. 19, 1034–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcedo J., Ayzenzon M., Von Ohlen T., Noll M., Hooper J. E. (1996). The Drosophila smoothened gene encodes a seven-pass membrane protein, a putative receptor for the hedgehog signal. Cell 86, 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcedo J., Zou Y., Noll M. (2000). Posttranscriptional regulation of smoothened is part of a self-correcting mechanism in the Hedgehog signaling system. Mol. Cell 6, 457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre C., Jacinto A., Ingham P. W. (1996). Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 10, 2003–2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apionishev S., Katanayeva N. M., Marks S. A., Kalderon D., Tomlinson A. (2005). Drosophila Smoothened phosphorylation sites essential for Hedgehog signal transduction. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascano M., Jr, Nybakken K. E., Sosinski J., Stegman M. A., Robbins D. J. (2002). The carboxyl-terminal domain of the protein kinase fused can function as a dominant inhibitor of hedgehog signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1555–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aza-Blanc P., Ramirez-Weber F. A., Laget M. P., Schwartz C., Kornberg T. B. (1997). Proteolysis that is inhibited by hedgehog targets Cubitus interruptus protein to the nucleus and converts it to a repressor. Cell 89, 1043–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K. (2007). An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3312–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casso D. J., Tanda S., Biehs B., Martoglio B., Kornberg T. B. (2005). Drosophila signal peptide peptidase is an essential protease for larval development. Genetics 170, 139–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., von Kessler D. P., Park W., Wang B., Ma Y., Beachy P. A. (1999). Nuclear trafficking of Cubitus interruptus in the transcriptional regulation of Hedgehog target gene expression. Cell 98, 305–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. K., Taipale J., Cooper M. K., Beachy P. A. (2002). Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling by direct binding of cyclopamine to Smoothened. Genes Dev. 16, 2743–2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Ren X. R., Nelson C. D., Barak L. S., Chen J. K., Beachy P. A., de Sauvage F., Lefkowitz R. J. (2004). Activity-dependent internalization of smoothened mediated by beta-arrestin 2 and GRK2. Science 306, 2257–2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Maier D., Neubueser D., Hipfner D. R. (2010). Regulation of smoothened by Drosophila G-protein-coupled receptor kinases. Dev. Biol. 337, 99–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V., Rosenbaum D. M., Hanson M. A., Rasmussen S. G., Thian F. S., Kobilka T. S., Choi H. J., Kuhn P., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K., et al. (2007). High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science 318, 1258–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien E. Y., Liu W., Zhao Q., Katritch V., Han G. W., Hanson M. A., Shi L., Newman A. H., Javitch J. A., Cherezov V., et al. (2010). Structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor in complex with a D2/D3 selective antagonist. Science 330, 1091–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. M., Jr (2010). Hedgehog signaling update. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 152, 1875–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J. V., McGregor A., Lee T., Milligan G., Eidne K. A. (1996). A disulfide bonding interaction role for cysteines in the extracellular domain of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Endocrinology 137, 2851–2858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef N., Neubuser D., Perez L., Cohen S. M. (2000). Hedgehog induces opposite changes in turnover and subcellular localization of patched and smoothened. Cell 102, 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalo F. R., Corbit K. C., Sirerol-Piquer M. S., Ramaswami G., Otto E. A., Noriega T. R., Seol A. D., Robinson J. F., Bennett C. L., Josifova D. J., et al. (2011). A transition zone complex regulates mammalian ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane composition. Nat. Genet. 43, 776–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardo N. G., Gajjar A. (2008). Chemotherapy for malignant brain tumors of childhood. J. Child Neurol. 23, 1149–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H., Wicking C., Zaphiropoulous P. G., Gailani M. R., Shanley S., Chidambaram A., Vorechovsky I., Holmberg E., Unden A. B., Gillies S., et al. (1996). Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell 85, 841–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C., Moro S., Nicholas R. A., Harden T. K., Jacobson K. A. (1999). The role of amino acids in extracellular loops of the human P2Y1 receptor in surface expression and activation processes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14639–14647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper J. E., Scott M. P. (1989). The Drosophila patched gene encodes a putative membrane protein required for segmental patterning. Cell 59, 751–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona J. P., Gruenberg J., Roelink H. (2002). Sonic hedgehog induces the segregation of patched and smoothened in endosomes. Curr. Biol. 12, 983–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham P. W., McMahon A. P. (2001). Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 15, 3059–3087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Tong C., Jiang J. (2003). Smoothened transduces Hedgehog signal by physically interacting with Costal2/Fused complex through its C-terminal tail. Genes Dev. 17, 2709–2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Tong C., Wang B., Luo L., Jiang J. (2004). Hedgehog signalling activity of Smoothened requires phosphorylation by protein kinase A and casein kinase I. Nature 432, 1045–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Hui C. C. (2008). Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 15, 801–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. L., Rothman A. L., Xie J., Goodrich L. V., Bare J. W., Bonifas J. M., Quinn A. G., Myers R. M., Cox D. R., Epstein E. H., Jr, et al. (1996). Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science 272, 1668–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnik S. S., Sakmar T. P., Chen H. B., Khorana H. G. (1988). Cysteine residues 110 and 187 are essential for the formation of correct structure in bovine rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 8459–8463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klco J. M., Wiegand C. B., Narzinski K., Baranski T. J. (2005). Essential role for the second extracellular loop in C5a receptor activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 320–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum L., Zhang C., Oh S., Mann R. K., von Kessler D. P., Taipale J., Weis-Garcia F., Gong R., Wang B., Beachy P. A. (2003). Hedgehog signal transduction via Smoothened association with a cytoplasmic complex scaffolded by the atypical kinesin, Costal-2. Mol. Cell 12, 1261–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigo V., Davey R. A., Zuo Y., Cunningham J. M., Tabin C. J. (1996). Biochemical evidence that patched is the Hedgehog receptor. Nature 384, 176–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massotte D., Kieffer B. L. (2005). The second extracellular loop: a damper for G protein-coupled receptors? Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar C., Holguin H., Mayor F., Jr, Ruiz-Gomez A., de Celis J. F. (2007). The G protein-coupled receptor regulatory kinase GPRK2 participates in Hedgehog signaling in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7963–7968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro S., Hoffmann C., Jacobson K. A. (1999). Role of the extracellular loops of G protein-coupled receptors in ligand recognition: a molecular modeling study of the human P2Y1 receptor. Biochemistry 38, 3498–3507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzny C. K., Holmgren R. (1995). The Drosophila cubitus interruptus protein and its role in the wingless and hedgehog signal transduction pathways. Mech. Dev. 52, 137–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y., Guerrero I., Hidalgo A., Taylor A., Whittle J. R., Ingham P. W. (1989). A protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains encoded by the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched. Nature 341, 508–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y., Nystedt S., Shivdasani A. A., Strutt H., Thomas C., Ingham P. W. (2004). Functional domains and sub-cellular distribution of the Hedgehog transducing protein Smoothened in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 121, 507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden S. K., Ascano M., Jr, Stegman M. A., Suber L. M., Hooper J. E., Robbins D. J. (2003). Identification of a functional interaction between the transmembrane protein Smoothened and the kinesin-related protein Costal2. Curr. Biol. 13, 1998–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden S. K., Casso D. J., Ascano M., Jr, Yore M. M., Kornberg T. B., Robbins D. J. (2006). Smoothened regulates activator and repressor functions of Hedgehog signaling via two distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7237–7243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden S. K., Fei D. L., Schilling N. S., Ahmed Y. F., Hwa J., Robbins D. J. (2008). G protein Galphai functions immediately downstream of Smoothened in Hedgehog signalling. Nature 456, 967–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlmeyer J. T., Kalderon D. (1998). Hedgehog stimulates maturation of Cubitus interruptus into a labile transcriptional activator. Nature 396, 749–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K., Kumasaka T., Hori T., Behnke C. A., Motoshima H., Fox B. A., Le Trong I., Teller D. C., Okada T., Stenkamp R. E., et al. (2000). Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk J., van den Heuvel M., Henrique D., Marigo V., Jones T. A., Tabin C., Ingham P. W. (1997). The smoothened gene and hedgehog signal transduction in Drosophila and vertebrate development. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 62, 217–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader A. J., Anderson G., Isin B., Khorana H. G., Bahar I., Klein-Seetharaman J. (2004). Identification of core amino acids stabilizing rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7246–7251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins D. J., Nybakken K. E., Kobayashi R., Sisson J. C., Bishop J. M., Therond P. P. (1997). Hedgehog elicits signal transduction by means of a large complex containing the kinesin-related protein costal2. Cell 90, 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R., Milenkovic L., Scott M. P. (2007). Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science 317, 372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel L., Rodriguez R., Gallet A., Lavenant-Staccini L., Therond P. P. (2003). Stability and association of Smoothened, Costal2 and Fused with Cubitus interruptus are regulated by Hedgehog. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 907–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H., Hui C., Nakafuku M., Kondoh H. (1997). A binding site for Gli proteins is essential for HNF-3beta floor plate enhancer activity in transgenics and can respond to Shh in vitro. Development 124, 1313–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Meunier L., Hendershot L. M. (2002). Identification and characterization of a novel endoplasmic reticulum (ER) DnaJ homologue, which stimulates ATPase activity of BiP in vitro and is induced by ER stress. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15947–15956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson J. C., Ho K. S., Suyama K., Scott M. P. (1997). Costal2, a novel kinesin-related protein in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell 90, 235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegman M. A., Vallance J. E., Elangovan G., Sosinski J., Cheng Y., Robbins D. J. (2000). Identification of a tetrameric hedgehog signaling complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21809–21812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegman M. A., Goetz J. A., Ascano M., Jr, Ogden S. K., Nybakken K. E., Robbins D. J. (2004). The Kinesin-related protein Costal2 associates with membranes in a Hedgehog-sensitive, Smoothened-independent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7064–7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. M., Hynes M., Armanini M., Swanson T. A., Gu Q., Johnson R. L., Scott M. P., Pennica D., Goddard A., Phillips H., et al. (1996). The tumour-suppressor gene patched encodes a candidate receptor for Sonic hedgehog. Nature 384, 129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale J., Chen J. K., Cooper M. K., Wang B., Mann R. K., Milenkovic L., Scott M. P., Beachy P. A. (2000). Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine. Nature 406, 1005–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therond P. P., Knight J. D., Kornberg T. B., Bishop J. M. (1996). Phosphorylation of the fused protein kinase in response to signaling from hedgehog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 4224–4228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torroja C., Gorfinkiel N., Guerrero I. (2004). Patched controls the Hedgehog gradient by endocytosis in a dynamin-dependent manner, but this internalization does not play a major role in signal transduction. Development 131, 2395–2408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unden A. B., Holmberg E., Lundh-Rozell B., Stahle-Backdahl M., Zaphiropoulos P. G., Toftgard R., Vorechovsky I. (1996). Mutations in the human homologue of Drosophila patched (PTCH) in basal cell carcinomas and the Gorlin syndrome: different in vivo mechanisms of PTCH inactivation. Cancer Res. 56, 4562–4565 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel M., Ingham P. W. (1996). smoothened encodes a receptor-like serpentine protein required for hedgehog signalling. Nature 382, 547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. T., Holmgren R. A. (2000). Nuclear import of cubitus interruptus is regulated by hedgehog via a mechanism distinct from Ci stabilization and Ci activation. Development 127, 3131–3139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter M., Reifenberger J., Sommer C., Ruzicka T., Reifenberger G. (1997). Mutations in the human homologue of the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched (PTCH) in sporadic basal cell carcinomas of the skin and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer Res. 57, 2581–2585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Chien E. Y., Mol C. D., Fenalti G., Liu W., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Brooun A., Wells P., Bi F. C., et al. (2010). Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science 330, 1066–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zhao Y., Tong C., Wang G., Wang B., Jia J., Jiang J. (2005). Hedgehog-regulated Costal2-kinase complexes control phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of Cubitus interruptus. Dev. Cell 8, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Tong C., Jiang J. (2007). Hedgehog regulates smoothened activity by inducing a conformational switch. Nature 450, 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Kalderon D. (2010). Costal 2 interactions with Cubitus interruptus (Ci) underlying Hedgehog-regulated Ci processing. Dev. Biol. 348, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu A. J., Zheng L., Suyama K., Scott M. P. (2003). Altered localization of Drosophila Smoothened protein activates Hedgehog signal transduction. Genes Dev. 17, 1240–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibat A., Missiaglia E., Rosenberger A., Pritchard-Jones K., Shipley J., Hahn H., Fulda S. (2010). Activation of the hedgehog pathway confers a poor prognosis in embryonal and fusion gene-negative alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene 29, 6323–6330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.