Abstract

The authors investigated the association between exposure to smoking in movies and the initiation and progression of adolescent smoking over time among 6,522 U.S. adolescents (between the ages of 10 and 14 years, at baseline) in a nationally representative, 4-wave random-digit-dial telephone survey. They conducted a hazard (survival) analysis testing whether exposure to movie smoking and demographic, personality, social, and structural factors predict (a) earlier smoking onset and (b) faster transition to experimental (1–99 cigarettes/lifetime) and established smoking (>100 cigarettes/lifetime). Results suggest that higher exposure to movie smoking is associated with less time to trying cigarettes for the first time (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.66; 95% CI [1.37, 2.01]) but not with faster escalation of smoking behavior following initiation (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.53; 95% CI [0.84, 2.79]). In contrast, age, peer smoking, parenting style, and availability of cigarettes in the home were predictors of earlier onset and faster transition to established smoking. Thus, the authors concluded that the effect of exposure to mass-mediated images of smoking in movies may decline once adolescents have started to smoke, whereas peers and access to tobacco remain influential.

Tobacco use is a leading cause of death and ill health, and primary prevention of smoking initiation has been an important strategy in reducing the health burden of tobacco use (World Health Organization, 2009). Most adult smokers in the United States started using tobacco as adolescents (U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000), and an extensive body of research has identified a range of personal and social risk factors for smoking initiation (e.g., Conrad, Flay, & Hill, 1992; Tyas & Pederson, 1998). Recently, researchers interested in mass media effects have demonstrated a prospective relation between exposure to smoking imagery in entertainment media and smoking onset among youth (Dalton et al., 2003; Sargent, Gibson, & Heatherton, 2009; Sargent & Hanewinkel, 2009; Tickle, Hull, Sargent, Dalton, & Heatherton, 2006), even after accounting for demographic, personality, parental, and peer influences.

Youth spend a large proportion of their time consuming media (Roberts, Foehr, & Rideout, 2005), and an extensive body of literature demonstrates prospective associations of exposure to entertainment media with a variety of attitudinal and behavioral outcomes, for example: aggression and criminality (Huesmann, Moise-Titus, Podolski, & Eron, 2003), sexual precocity (Martino, Collins, Kanouse, Elliott, & Berry, 2005), and alcohol use (Dal Cin et al., 2009). Given that, it is perhaps unsurprising that exposure to smoking in movies has been associated with smoking-related attitudes and behavior, in both survey (e.g., Dalton et al., 2009; Dalton et al., 2003; Distefan, Gilpin, Sargent, & Pierce, 1999; Hanewinkel, Morgenstern, Tanski, & Sargent, 2008; Hanewinkel & Sargent, 2007; Sargent et al., 2005; Sargent et al., 2001; Sargent et al., 2002; Sargent et al., 2009; Sargent & Hanewinkel, 2009; Sargent et al., 2007; Thrasher, Jackson, Arillo-Santillán, & Sargent, 2008; Tickle et al., 2006; Tickle, Sargent, Dalton, Beach, & Heatherton, 2001; Wills et al., 2007) and experimental (Dal Cin, Gibson, Zanna, Shumate, & Fong, 2007; Gibson & Maurer, 2000; Pechmann & Shih, 1999) research. However, the majority of research on the effects of exposure to movie smoking on adolescents has focused on predicting initiation as opposed to smoking maintenance or escalation. Several recent studies (Adachi-Mejia et al., 2009; Dalton et al., 2009; Sargent et al., 2007) reveal a longitudinal association between exposure to depictions of smoking in movies and the likelihood of becoming an established smoker (i.e., having smoked more than 100 cigarettes). Although these studies provide convincing evidence for the association, they are unable to distinguish effects on initiation from effects on progression. Even in studies that controlled for smoking status at baseline, it is still likely that some of the established smokers may have initiated during the study period; therefore, the effect of movie smoking exposure on escalation of smoking, given that one has already tried, remains unclear.

The question of whether movie smoking exposure continues to be impactful once an adolescent has tried smoking is an important one. However, it is not entirely clear whether one should expect that movie smoking exposure will exacerbate progression. On the basis of the media effects literature (e.g., Bandura, 1986), exposure to smoking models should reinforce existing smoking behavior, and therefore, exposure to movie smoking should exert an effect on progression or escalation of smoking beyond its effects on initiation. Survey research in Germany (Sargent & Hanewinkel, 2009) has identified a relation between movie smoking exposure and escalation of smoking after initiation. Further, in their experimental study of exposure to movie smoking and smoking intentions, Dal Cin and colleagues (2007) found that identification with a smoking character led to increased identification with smoking, and that among smokers, this predicted intentions to continue smoking.

In contrast, Sargent and colleagues (2009) found no relation between movie smoking exposure and progression in a regional U.S. sample. These results are consistent with research in the area of nicotine addiction, which suggests that once an individual has tried smoking (perhaps as little as one cigarette), the physiological consequences of exposure to nicotine drive subsequent use (DiFranza et al., 2000; DiFranza & Wellman, 2005). According to this perspective, once initiation has occurred, addiction becomes the dominant predictor and escalation will happen, independent of social influences. Furthermore, past behavior tends to be a powerful predictor of future behavior, in particular for behaviors performed in similar contexts and with regular frequency (Ouellette & Wood, 1998); the consistency of behavior over time suggests that once initiated, smoking behavior will be maintained, and movie exposure will have an attenuated influence.

Given the disparate effects observed in past studies (some of which have been limited in terms of available waves of data and the regional nature of their samples), we aimed to undertake the present analysis in which we model the relation of movie smoking exposure to smoking onset and escalation in a multiwave, nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Note that one of the studies noted earlier (Sargent et al., 2007) identified a relation between movie smoking exposure and established smoking in the present sample; however, that analysis conflated initiation and progression (i.e., the authors did not model the relation of movie smoking exposure with smoking progression over and above the former’s relation to smoking initiation). We revisit these data in the present study, examining the predictors of change (transitions) in smoking status over a 2-year period, to clarify whether the relation previously obtained is largely a function of the relation between exposure and initiation, or whether exposure is also related to progression. We consider a range of established predictors of smoking behavior, in an attempt to clarify whether specific predictors are more (or less) impactful at different points in the smoking trajectory. By using four waves of data, we were able to not only model changes over several points in time, but also include time-varying predictors.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The present sample included 6,522 adolescents who completed a random-digit-dial telephone survey of 10–14-year-old children living in the United States. At the first wave of the survey (T1), our sample had a mean age of 12.05 years (SD = 1.39 years) and mirrored the general U.S. population aged 10–14 years in terms of gender, ethnic/racial background, and socioeconomic status (for details, see Sargent et al., 2005). Respondents were first contacted between June 2003 and October 2003, with three 8-month follow-up surveys (T2–T4). Details regarding the survey participants and procedure have been previously reported (Sargent et al., 2005). Briefly, 377,850 U.S. telephone numbers were randomly selected; after purging of non-residential telephone numbers, 69,516 households were screened for the presence of an eligible adolescent (29% of households refused). This process identified 9,849 eligible households, from which 6,522 adolescents (66% of those eligible) completed the T1 survey. Trained interviewers used a computer-assisted telephone interview system to administer surveys (in either English or Spanish), which allowed for touch-tone responses to potentially sensitive questions. The present analysis uses data from T1 through T4 (nT1 = 6,522; nT2 = 5,503; nT3 = 5,019; nT4 = 4,575; at each wave, survey staff attempted to recontact all the original participants). We used multiple imputation of missing data so that the total sample size remains 6,522 at all waves (see the “Statistical Analysis” section for details on the imputation procedure).

Materials

Demographic, Child Personality, and Social Influence Predictors of Smoking

At T1, we assessed numerous factors which were expected, on the basis of past research, to be significantly correlated with smoking behavior and movie exposure. In particular, we obtained information on age, gender (“0” = male, “1” = female), racial/ethnic minority status, household income, and parent education (see Table 2 for response categories).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for baseline measures

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 704 | 11 |

| Hispanic | 1,222 | 19 |

| Other | 559 | 9 |

| Female | 3,506 | 49 |

| School Performance | ||

| Below average | 181 | 3 |

| Average | 1,625 | 25 |

| Good | 2,734 | 42 |

| Excellent | 1,982 | 30 |

| Parent education | ||

| Up to 8th grade | 402 | 6 |

| 9th to 11th grade | 478 | 7 |

| 12th grade (no diploma) | 260 | 4 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 1,481 | 23 |

| Vocational/technical training | 234 | 4 |

| Some college (no degree) | 1,127 | 17 |

| Associate’s degree | 550 | 8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1,197 | 18 |

| Any postgraduate | 793 | 12 |

| Household income | ||

| $10,000 or less | 475 | 7 |

| $10,001–$20,000 | 722 | 11 |

| $20,001–$30,000 | 804 | 12 |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 1,360 | 21 |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 1,296 | 20 |

| More than $75,000 | 1,865 | 29 |

| Any parent smokes | 2,283 | 35 |

| Any sibling smokes | 978 | 15 |

| Number of friends who smoke | ||

| None | 5,078 | 78 |

| Some | 1,238 | 19 |

| Most | 206 | 3 |

| Could get cigarettes at home | ||

| Definitely no | 5,378 | 82 |

| Probably no | 600 | 9 |

| Probably yes | 392 | 6 |

| Definitely yes | 152 | 2 |

| No weekly pocket money | 2,544 | 39 |

We also measured sensation seeking, rebelliousness, school performance, and number of extracurricular activities. We measured sensation seeking using a 4-item, 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not like you) to 4 (just like you), tapping the thrill/adventure-seeking (e.g., “I like to do scary things,” “I like to do dangerous things”) and boredom susceptibility (e.g., “I often think there is nothing to do”) constructs identified by Zuckerman (1994), and the intensity seeking (e.g., “I like to listen to loud music”) construct identified by Arnett (1994). We measured rebelliousness using a 6-item, 4-point Likert-type scale assessing tendency toward antisocial behavior (e.g., “I like to break the rules,” “I argue a lot with other kids”; Pierce, Farkas, & Evans, 1993). For school performance, participants described their grades last year as either: excellent, good, average, or below average. They also reported whether they were involved in various extracurricular activities, including sports (organized or casual), music, church, school clubs (e.g., science, newspaper), and community clubs (e.g., scouting).

Social influence predictors included peer, sibling, and parent smoking, and parental warmth and supervision (Jackson, Henriksen, & Foshee, 1998). We assessed peer smoking by asking participants, “How many of your friends smoke cigarettes?” reported on a 3-point scale (“1” = none, “2” = some, “3” = most). Sibling smoking was a dichotomous variable indexed by the following question: “Do any of your older brothers or sisters smoke cigarettes?” (“0” = no, “1” = yes; participants reporting no older siblings were assigned a value of 0). Parent smoking was indexed by asking respondents (a) whether their mother (or stepmother) and (b) whether their father (if living with the child) smoke, and combining these into a single indicator (“0” = no parent smokes, “1” = one or both parents smoke). Parenting style was assessed in reference to the “the adult guardian you spend the most time with” in an average week. The 5-item parental warmth measure included items such as “She makes me feel better when I’m upset” and “She wants to hear about my problems,” whereas the 4-item parental supervision scale included items such as “She makes sure I tell her where I’m going” and “She asks me what I do with my friends” (reported on a 4-point scale ranging from “1” = not like her to “4” = just like her, for all items). We also included measures of access to tobacco: availability of cigarettes in the home (“If you wanted to, could you get cigarettes from home without your parents knowing?”; definitely no to definitely yes) and amount of weekly spending money (an open-ended dollar amount in response to “About how much money do you have each week to spend any way you want?”).

Some of these variables (sensation seeking, rebelliousness school performance, extracurriculars, peer smoking, sibling smoking, parenting, availability of cigarettes in the home and weekly spending money) were also measured at subsequent waves and were included as time-varying covariates in the model through Wave 3. Over the four survey waves, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .57 to .62 for sensation seeking, .71 to .76 for rebelliousness, .75 to .83 for parental warmth, and .59 to .67 for parental supervision.1

Media Exposure

We included two measures of media exposure. One item was used to account for exposure to television: hours of television usually watched on school days (reported on a 5-point scale ranging from “1” = none to “5” = more than four hours; entered as a time-varying predictor through T3). The second measure was designed to index exposure to movie smoking depictions specifically. At each survey wave, adolescents reported whether they had ever seen each of 50 different movies, randomly selected (without replacement) from a predetermined set of popular contemporary movie titles. At T1, the pool of available titles (n = 534) included the top-grossing movies each year from 1998 to 2002, and 34 movies grossing more than $15 million USD in the first quarter of 2003. At subsequent waves, respondents were asked about 50 randomly selected titles drawn from the top theatre releases and video rentals for the interval between the survey waves (T2 = 161 movies, T3 = 155 movies). The random samples were stratified by Motion Picture Association of America rating (and at T2 and T3, source: theatre vs. video). Movies that a respondent reported seeing at a prior wave were excluded from the sampling frames for his or her subsequent surveys.

Content analysis of movies was used to quantify depictions of smoking in movies. One of two trained coders viewed each movie and recorded the number of smoking occurrences. A smoking occurrence was defined as a character’s use or handling of a tobacco product or the presence of other smoking imagery (e.g., billboard ads). Interrater reliability (the mean kappa for coder agreement on whether smoking was occurring in 1-s intervals) was .86 (SD = .17), based on double coding 10% of the movies.

We linked the number of smoking occurrences in each movie with the survey data to estimate exposure to movie depictions of smoking for each respondent. We did so by first computing the proportion of the total smoking occurrences on the respondent’s unique list of 50 movies that the respondent saw. This proportion was obtained by dividing the sum of the smoking occurrences in movies they reported seeing by the sum of movie smoking occurrences for all of the 50 movies on their unique list. Then, for overall exposure, each respondent got the raw score that corresponded to the same proportion from the parent pool of 534 movies, which we obtained by multiplying the total smoking occurrences in the parent pool by the respondents proportion from their list of 50 movies. Last, because the size of the parent pool of movies changed dramatically after Wave 1, we rescaled the subsequent raw scores at Waves 2 and 3 as if they had been obtained from a parent pool of 534. To do this, we divided the Wave 2 and 3 raw scores by the sizes of the Waves 2 and 3 parent pools, 161 and 155 respectively, and then multiplied by the size of the Wave 1 parent pool, 534.

Outcome Variables

Smoking status at each wave was determined on the basis of responses to the question, “How many cigarettes have you smoked in your lifetime,” and respondents were classified as Nonsmokers (those reporting 0 cigarettes), experimental smokers (those reporting 1–99 cigarettes), and established smokers (those reporting 100 or more cigarettes). As multiple waves of data were available, we also evaluated transitions from one smoking status to another.

Statistical Analysis

We used a Cox hazard model predicting time to transition. This allowed us to simultaneously model multiple processes (initiation and progression) and repeated events; the respondents could have more than one forward transition (e.g., from nonsmoker to experimental smoker, and then from experimental smoker to established smoker). We used a robust sandwich estimator to account for this within-subject dependency in order to obtain accurate standard errors (Therneau & Grambsch, 2000). Some respondents (7%) reported “backward” transitions; that is, they reported smoking fewer lifetime cigarettes at a particular wave than they had reported previously. Backward transitions (which represented 27% of all transitions) were also modeled in the present analysis; their inclusion did not modify the pattern of results for initiation and progression. Complete explication of the backward transitions part of the model was beyond the scope of the present article. Predictor effects were allowed to be different in all three parts of the model.

To make estimated effects more comparable across predictors on very different measurement scales, we linearly rescaled all the ordered categorical predictors with more than two categories so that the lowest category was scored “0” and the highest category was scored “1.” For continuous predictors, we linearly rescaled the predictors so the 5th percentile score was “0” and the 95th percentile score was “1” and then recoded (winsorized) more extreme scores in either direction back to 0 or 1. Thus, all estimated effects represent going from the low to the high end of the scale, avoiding extremes, regardless of the gradations in between.

We used the multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) procedure in R to stochastically impute missing data (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, in press; this procedure is equivalent to the ICE procedure in Stata). To improve the quality of the imputations, a number of baseline auxiliary variables were included only in the imputation model that were predictive of missing data but not necessarily the outcome. All variables were treated as numeric and the predictive mean matching procedure was used to create 15 imputed values for each missing score. Convergence was assessed by checking plots of the mean and variance of the imputations for each variable across the 15 streams for signs of problems such as trends or lack of proper mixing. No problems were apparent. For descriptive statistics only, we averaged across the 15 imputations to get a single best estimate for each missing data point. We fit the Cox hazard model to each of the 15 imputed complete datasets and followed standard procedures for pooling the estimates and obtaining standard errors (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, in press).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Overview of the Hazard Model

Baseline descriptive statistics for this sample have been reported previously (Sargent et al., 2005); see Tables 1–3 for those from this imputed dataset. In total, there were 1,316 forward transitions over the 2-year study period. Of these, 1,150 were from never to experimental smoker, 142 were from experimental to established smoker, and 24 from never to established smoker; 4,807 never, 338 experimental, and 22 established smokers reported no transition (their smoking status did not change over the course of the study), 1,164 individuals reported one forward transition, and 76 reported two forward transitions.

Table 1.

Lifetime smoking, by wave (imputed data)

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime smoking | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Nonsmoker | 5,830 | 89 | 5,615 | 86 | 5,349 | 82 | 5,099 | 78 |

| Experimenter | 658 | 10 | 852 | 13 | 1,064 | 16 | 1,265 | 19 |

| Established | 34 | 1 | 55 | 1 | 109 | 2 | 158 | 2 |

Note. Total N of imputed data is 6,522 at all waves.

Table 3.

Baseline measures of behavioral characteristics

| Variable | M | SD | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 12.05 | 1.39 | 12 | 11–13 |

| Movie smoking exposure (n) | 656.93 | 574.87 | 501 | 210–954 |

| TV watched per day (hours) | 2.06 | 0.97 | 2 | 2–3 |

| Parent demandingness | 2.21 | 0.59 | 2 | 2–3 |

| Parent responsiveness | 2.34 | 0.55 | 2 | 2–3 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.99 | 0.62 | 1 | 1–2 |

| Rebelliousness | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0 | 0–0 |

| Extracurricular activities (n) | 1.87 | 0.50 | 2 | 2–2 |

Note. IQR = interquartile range.

Nonmedia Predictors of Smoking in the Multivariate Model

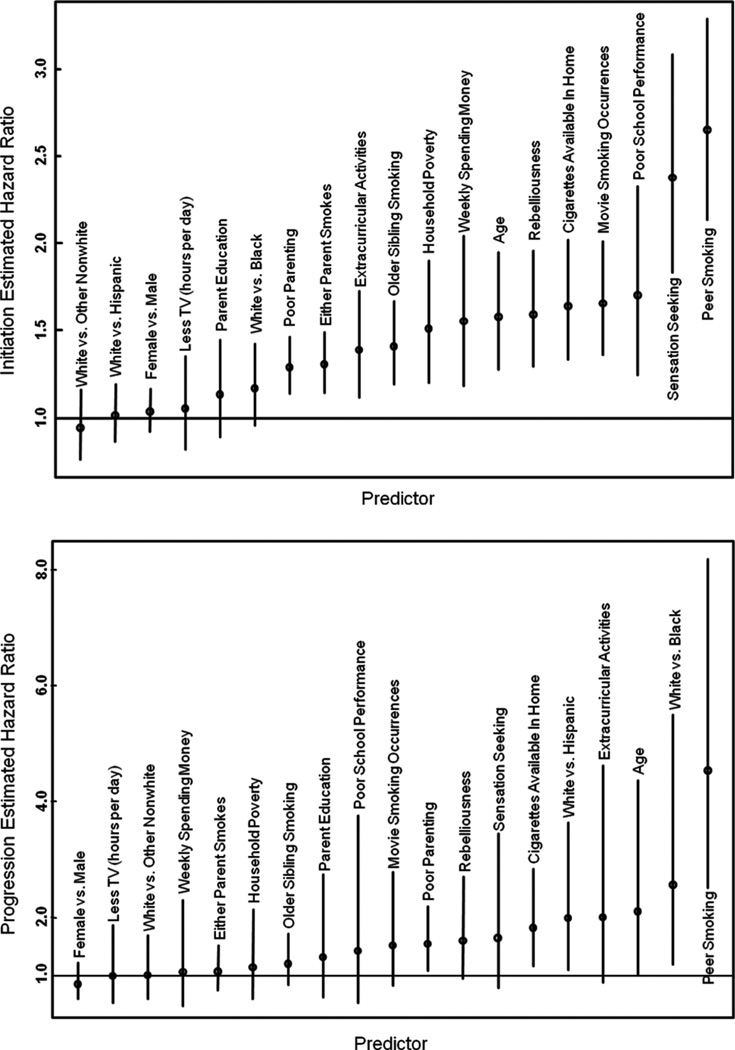

Graphical representations of point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for all predictors in the initiation and progression parts of the model are available in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Absolute values and 95% confidence intervals of the hazard odds for smoking initiation and smoking progression for each risk factor in the model.

The same information is presented in Table 4. Age was a significant predictor of smoking behavior, with older participants being more likely to initiate sooner and to progress faster; gender was unrelated to smoking behavior. Race/ethnicity was associated with progression, but not initiation: Black, Hispanic, and other visible minority youth had the same time to initiation as Whites, but Black and Hispanic youth progressed more slowly. With regard to socioeconomic indicators, higher household income was associated with later initiation, but not with progression, whereas parent education was unrelated to smoking behavior.

Table 4.

Estimated effects and 95% confidence intervals for predictors of smoking initiation and progression

| Hazard rate 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Initiation | Progression |

| Household poverty | 1.51 (1.20, 1.90) | 1.14 (0.61, 2.14) |

| Parent education | 1.14 (0.89, 1.45) | 1.32 (0.63, 2.75) |

| Age | 1.58 (1.28, 1.95) | 2.11 (1.02, 4.36) |

| Female vs. male | 1.04 (0.93, 1.17) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.22) |

| White vs. black | 1.17 (0.96, 1.43) | 2.57 (1.20, 5.49) |

| White vs. Hispanic | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | 1.99 (1.09, 3.63) |

| White vs. other non-White | 0.95 (0.77, 1.17) | 1.01 (0.60, 1.69) |

| Less TV (hours per day) | 1.06 (0.82, 1.36) | 1.00 (0.53, 1.87) |

| Movie smoking occurrences | 1.66 (1.37, 2.01) | 1.53 (0.84, 2.79) |

| Poor school performance | 1.71 (1.25, 2.33) | 1.43 (0.54, 3.77) |

| Extracurricular activities | 1.39 (1.12, 1.73) | 2.01 (0.88, 4.62) |

| Peer smoking | 2.65 (2.14, 3.29) | 4.54 (2.52, 8.19) |

| Older sibling smoking | 1.41 (1.19, 1.67) | 1.21 (0.84, 1.73) |

| Either parent smokes | 1.31 (1.15, 1.50) | 1.07 (0.75, 1.52) |

| Sensation seeking | 2.38 (1.83, 3.08) | 1.65 (0.79, 3.46) |

| Rebelliousness | 1.60 (1.30, 1.96) | 1.61 (0.95, 2.71) |

| Poor parenting | 1.29 (1.14, 1.46) | 1.55 (1.09, 2.20) |

| Cigarettes available in home | 1.64 (1.34, 2.02) | 1.83 (1.18, 2.84) |

| Weekly spending money | 1.56 (1.19, 2.04) | 1.06 (0.49, 2.31) |

Note. A hazard rate of 1.0 indicates “no effect” thus, confidence intervals not including 1.0 indicate significant effects.

Higher levels of sensation seeking and rebelliousness were associated with earlier initiation, not with progression. Better school performance predicted later initiation, whereas more extracurricular activities predicted earlier initiation; neither variable was related to progression.

Peer, sibling, and parent smoking all predicted shorter time to initiation, but only peer smoking was related to progression, with more peer smoking predicting faster progression. Higher parental warmth and supervision predicted later initiation and slower progression. Youth who reported more weekly spending money initiated sooner, but this variable was unrelated to progression. In contrast, availability of cigarettes in the home was associated with starting to smoke sooner, and progressing.

Movie Smoking Exposure and General Media Exposure

After controlling for other variables, exposure to movie smoking was associated with earlier initiation, but was unrelated to progression. High exposure to movie smoking increased the adjusted hazard of smoking initiation by a factor of 1.66 (95% confidence interval 1.37, 2.01). The hazard ratio association between high exposure to movie smoking and progression transition was 1.53 (0.84, 2.79). As discussed in more detail in another report, the movie smoking hazard ratio for smoking onset was significantly higher among White (adjusted hazard ratio 2.02 [1.56, 2.62]) compared to minority adolescents. Reported TV use was unrelated to smoking initiation and progression.

Discussion

As expected, exposure to smoking in movies was associated with an increased rate of smoking initiation. However, it was not associated with subsequent progression of smoking, which was predicted most strongly by peer smoking, race and ethnicity, age, and availability of cigarettes in the home. This is consistent with research documenting the relative stability of behavior once smoking experimentation begins (Ouellette & Wood, 1998), the potentially rapid onset of nicotine addiction (DiFranza et al., 2000; DiFranza & Wellman, 2005), and the relation between access to tobacco and smoking behavior among youth (e.g., Widome, Forster, Hannan, & Perry, 2007). This raises the question of whether the association between seeing movie smoking and established smoking seen in previous work (Adachi-Mejia et al., 2009; Dalton et al., 2009; Sargent et al., 2007) is due to the relatively long time periods studied (2 years or more), during which many could have initiated and transitioned to established smoking. However, our results are inconsistent with those of a 1-year longitudinal study of German young people in the same age group as our respondents (Sargent & Hanewinkel, 2009). It may be that the limited number of progression transitions observed in the current U.S. sample limits our ability to detect the effects of our predictor variables. Indeed, in the present analysis, the point estimates of the effect of movie smoking exposure on initiation and progression are of about the same magnitude, but the latter has a larger confidence interval. Although the German study did not report the number of transitions in their sample, 2000–2007 current (30 day) smoking rates among 13–15-year-old youth in Germany were more than 30%; the rates in the United States were less than half that (www.tobaccoatlas.org). It may be possible that the German data provide better power to detect effects of movie smoking exposure on smoking escalation. That said, differences in smoking rates are likely indicative of other differences in individual, cultural, and social contexts between these samples, and one or more of these differences might moderate the relation between exposure to movie smoking and smoking progression. As an example, smoking rates suggest that German young people are more likely than American young people to be among peers who smoke; thus, the social environment of German youth provides greater affordances for smoking progression (i.e., an accepting peer group, access to tobacco products) than does the social environment of American youth. In the presence of those affordances it is possible that other variables, including mass media influences such as movie smoking exposure, continue to exert influence.

Do the present results suggest that movie smoking exposure is inconsequential because we found that it was only associated with smoking onset? No. Indeed, just the opposite—the relation between exposure to movie smoking and earlier initiation of smoking is of real concern, because earlier initiation is associated with more problematic smoking outcomes, including greater likelihood of being a heavy smoker and less likelihood of quitting (e.g., Breslau & Peterson, 1996; Chen & Millar, 1998). Thus, to the extent that the relations observed are causal (see National Cancer Institute, 2008), movie smoking exposure appears to set in motion a behavior (smoking) that can then be maintained and modified by other influences, in particular, the immediate social context of smoking (e.g., being among smoking peers) and addiction to nicotine. The present results suggest that the main focus of media smoking interventions (in the United States, at least) should be on prevention of initiation, whereas interventions for those who have initiated should perhaps focus on other modifiable factors, such as those related to peer smoking, parenting, and the availability of cigarettes in the home.

The present research points out the relative effect of different established predictors of smoking behavior at different points in the smoking trajectory, and highlights the importance of distinguishing between initiation and progression when conducting research on smoking uptake. We suggest that the present analytic strategy is a useful tool for accomplishing this objective, but that rates of progression should be attended to in determining sufficient sample size.

It must be noted that the present data, although prospective, are still correlational, and causal conclusions cannot be drawn from an individual correlational study. Further, the present analyses identify the relations between the predictors and outcomes, but do not include tests of the underlying processes that account for these relations. For example, the present results do not explain how movie smoking exposure could lead to initiation. Other reports that focus on process suggest that inclusion of possible mediators, such as friend smoking, as covariates may result in an underestimation of the movie influence (Wills et al., 2007; Wills et al., 2008). It is also important to point out that the present findings do not rule out the possibility of protective or ameliorative effects from exposure to antismoking depictions in movies. Previous research has demonstrated the potential public health benefit of incorporating health promotion messages in entertainment storylines (e.g., Diekman, McDonald, & Gardner, 2000; Kennedy, O’Leary, Beck, Pollard, & Simpson, 2004). Our measure of movie exposure does not contain antismoking depictions (it is rare to see these in movies); it may be that such exposures could to positive health outcomes such as less (or slower) initiation and progression. We look forward to future research examining these issues.

Acknowledgments

The research reported has been funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health: National Cancer Institute (CA77026) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA015591). The survey project has also received support from the American Legacy Foundation, a U.S. nonprofit, independent, public health foundation. The authors thank Nicholas Valentino and L. Rowell Huesmann for their helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. None of the authors has connections with the tobacco industry. There are no contractual constraints on publishing the research being reported.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Previously published sensitivity analyses using these (Sargent, et al., 2007) and similar (Dalton, et al., 2003) data reveal that despite the use of single item measures and scales with moderate reliability coefficients, there is little evidence that effects of movie smoking exposure can be attributed to unmeasured confounding variables.

Contributor Information

Sonya Dal Cin, Department of Communication Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Mike Stoolmiller, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, USA.

James D. Sargent, Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA

References

- Adachi-Mejia AM, Primack BA, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff L, Longacre MR, Weiss JE, et al. Influence of movie smoking exposure and team sports participation on established smoking. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:638–643. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. Sensation seeking: A new conceptualization and a new scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16:289–289. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL. Smoking cessation in young adults: Age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:214–220. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Millar W. Age of smoking initiation: Implications for quitting. Health Reports. 1998;9:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KM, Flay B, Hill D. Why children start smoking cigarettes: Predictors of onset. Addiction. 1992;87:1711–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Gibson B, Zanna MP, Shumate R, Fong G. Smoking in movies, implicit associations of smoking with the self, and intentions to smoke. Psychological Science. 2007;18:559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Stoolmiller M, Wills TA, et al. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Matzkin AL, Sargent JD, et al. Early exposure to movie smoking predicts established smoking by older teens and young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e551–e558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: A cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362:281–285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekman AB, McDonald M, Gardner WL. Love means never having to be careful: The relationship between reading romance novels and safe sex behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Ockene JK, Savageau JA, St. Cyr D, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:313–319. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ. A sensitization-homeostasis model of nicotine craving, withdrawal, and tolerance: Integrating the clinical and basic science literature. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7:9–26. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distefan JM, Gilpin EA, Sargent JD, Pierce JP. Do movie stars encourage adolescents to start smoking? Evidence from California. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:1–11. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson B, Maurer J. Cigarette smoking in the movies: The influence of product placement on attitudes toward smoking and smokers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:1457–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M, Tanski SE, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of parental movie restriction on teen smoking and drinking in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103:1722–1730. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to popular contemporary movies and youth smoking in Germany. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Moise-Titus J, Podolski CL, Eron LD. Longitudinal relations between children’s exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977–1992. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:201–221. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:319–337. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MG, O’Leary A, Beck V, Pollard K, Simpson P. Increases in calls to the CDC National STD and AIDS Hotline following AIDS-related episodes in a soap opera. Journal of Communication. 2004;54:287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Kanouse DE, Elliott M, Berry SH. Social cognitive processes mediating the relationship between exposure to television’s sexual content and adolescents’ sexual behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:914–924. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco Control Monograph. 2008;19 Retrieved from http://www.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf.

- Ouellette JA, Wood W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann C, Shih CF. Smoking scenes in movies and antismoking advertisements before movies: Effects on youth. Journal of Marketing. 1999;63:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Farkas A, Evans N. Tobacco use in California 1992: A focus on preventing uptake in adolescents. Sacramento: California Department of Human Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: Media in the lives of 8–18 year olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. (No. 7251) [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, Gibson JJ, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Carusi CP, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323:1394–1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Viewing tobacco use in movies: Does it shape attitudes that mediate adolescent smoking? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Gibson J, Heatherton TF. Comparing the effects of entertainment media and tobacco marketing on youth smoking. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:47–53. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. Comparing the effects of entertainment media and tobacco marketing on youth smoking in Germany. Addiction. 2009;104:815–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Worth KA, Dal Cin S, Wills TA, Gibbons FX, et al. Exposure to smoking depictions in movies: Its association with established adolescent smoking. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:849–856. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: Extending the Cox model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Jackson C, Arillo-Santillán E, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking imagery in popular films and smoking in Mexico. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickle JJ, Hull JG, Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Heatherton TF. A structural equation model of social influences and exposure to media smoking on adolescent smoking. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2006;28:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, Heatherton TF. Favourite movie stars, their tobacco use in contemporary movies, and its association with adolescent smoking. Tobacco Control. 2001;10:16–22. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas SL, Pederson LL. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: A critical review of the literature. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:409–420. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health, & Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document.

- van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Widome R, Forster JL, Hannan PJ, Perry CL. Longitudinal patterns of youth access to cigarettes and smoking progression: Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort (MACC) study (2000–2003) Preventive Medicine. 2007;45:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Movie smoking exposure and smoking onset: A longitudinal study of mediation processes in a representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:269–277. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Worth KA, Dal Cin S. Movie exposure to smoking cues and adolescent smoking onset: A test for mediation through peer affliliations. Health Psychology. 2007;26:769–776. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]