Abstract

Relatively high expression of Hsp27 in breast and prostate cancer is a predictor of poor clinical outcome. This study elucidates a hitherto unknown mechanism by which Hsp27 regulates proteasome function and modulates tumor-specific T cell responses. Here we demonstrated that short term silencing of Hsp25 or Hsp27 using siRNA or permanent silencing of Hsp25 using lentivirus-RNAi technology enhanced PA28α mRNA expression, PA28α protein expression, proteasome activity, abrogated metastatic potential, induced the regression of established breast tumors by tumor-specific CD8+ T cells and stimulated long-lasting memory responses. The adoptive transfer of reactive CD8+ T cells from mice bearing Hsp25-silenced tumors efficiently induced the regression of established tumors in non-treated mice which normally succumb to tumor burden. The overexpression of Hsp25 and Hsp27 resulted in the repression of normal proteasome function, induced poor antigen presentation and resulted in increased tumor burden. Taken together, this study establishes a paradigm shift in our understanding of the role of Hsp27 in the regulation of proteasome function and tumor-specific T cell responses and paves the way for the development of molecular targets to enhance proteasome function and concomitantly inhibit Hsp27 expression in tumors for therapeutic gain.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, CD8+ CTL, Heat Shock Proteins, Lentivirus, siRNA

Introduction

The twenty-five kilo Dalton heat shock protein (Hsp25) belongs to the family of small HSPs and is the murine homologue of human Hsp27, which was originally identified as an estrogen responsive gene in breast cancer cells (1). Unlike the large HSPs, which function through ATP-dependent mechanisms, Hsp25/27 operates through ATP-independent mechanisms (2, 3). Importantly, elevated Hsp27 levels have been found in various tumors, including breast, prostate, gastric, uterine, ovarian, head and neck, and tumors arising from the nervous system and urinary system (4). In ER-α positive benign neoplasia, elevated levels of Hsp27 have been shown to promote the progression to more malignant phenotypes (5). These studies were supported by findings that demonstrate enhanced Hsp27 protein in breast cancer cells correlated well with increased anchorage independent tumor growth (6), increased resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs (including cisplatin and doxorubicin) and increased metastatic potential in vitro (7–9). Together, these studies predict that elevated Hsp27 in breast cancer will give rise to aggressive disease that is refractory to treatment and so have poor prognosis (4). Indeed, elevated Hsp27 expression in tumors correlates with shorter disease-free survival and recurrence in node-negative breast cancer (10, 11), whereas the induction of Hsp27 following chemotherapy predicts poor prognosis and shorter disease-free survival (12). Currently, several selective Hsp27 inhibitors have reached clinical trials, including the Hsp27 inhibitor, OGX-427, which has completed Phase I trials (clinicaltrials.gov - NCT00487786) and is now in Phase II trials of castrate resistant prostate cancer (clinicaltrials.gov - NCT01120470) and bladder cancer (clinicaltrials.gov - NCT00959868).

The inability of CD8+ T cells to recognize tumor-associated antigenic (TAA) peptides presented on MHC class I molecules remains a formidable barrier limiting the success of immunotherapy (13). In normal cells the proteasome system efficiently generates peptides from intracellular antigens, which are loaded onto MHC class I molecules for presentation to T cells (14). Within the proteasome system, the proteasome activator 28 (PA28) subunit, is a modulator of the proteasome-catalyzed generation of peptides presented via MHC class I molecules and the selective increase in cellular levels of PA28-alpha (PA28α) results in improved antigen presentation (15, 16). In addition, PA28 is essential for the recognition of epitopes on melanoma cells by specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) (17), and may alter the quality of products generated by proteasome cleavage (18, 19). The overexpression of the PA28α/β subunit enhanced MHC class I-restricted presentation of two viral epitopes and purified PA28α and β subunit accelerated T cell epitope generation by the 20S proteasome in vitro (15). Taken together, these studies suggest that an efficient, well-functioning proteasome system is beneficial for specific CD8+ CTL recognition of tumors and ultimate cytolysis (for review see (20)).

In this study, we demonstrated that short term silencing of Hsp25 or Hsp27 using siRNA or permanent silencing of Hsp25 using lentivirus-RNAi technology enhanced proteasome activity via increased PA28α subunit expression, abrogated metastatic potential, induced the regression of established breast cancer cells via tumor-specific CD8+ T cells and stimulated long-lasting memory responses.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Culture Conditions

4T1 cells are a highly metastatic breast cancer cell line derived from a spontaneously arising BALB/c mammary tumor. BNL 1MEA.7R.1 (BNL) cells are a mouse transformed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell line derived from BALB/c mice. MCF7 cells are a non-aggressive human breast cancer cell line. MDA-MB-232 cells are a highly aggressive human breast cancer cell line. All breast cancer cells were purchased directly from the American Type Cell Culture (ATCC; Rockville, MD), which routinely performs cell line characterization. All breast cancer cells were passaged in our lab for not more than 6 months after receiving them from ATCC. 4T1 cells were maintained in monolayer cultures in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Cellgro, Los Angeles, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics/antimycotics (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). BNL cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, antibiotics and antimycotics (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). MCF7 cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM; Eagle) with 2 mM L-glutamine and Earle's BSS adjusted to contain 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids and 1 mM sodium pyruvate and supplemented with 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin and 10% fetal bovine serum. MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in ATCC-formulated Leibovitz’s L-15 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, antibiotics and antimycotics (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Inc.). All breast cancer cells were maintained in an incubator adjusted to 37°C with humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2.

Preparation of Small Hairpin RNA from Mouse Hsp25 using Lentivirus Gene Transfer Vector

A HIV-derived three plasmid system was kindly provided by D. Trono (Department of Microbiology and Molecular Medicine, University of Geneva, Switzerland). The packaging plasmid psPAX2 encodes HIV-1 gag and pol genes. The envelope plasmid pMD2G encodes vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G envelope protein. The transfer vector pLVTHM encodes EF1 alfa and H1 promoters, green fluorescent protein (GFP) as fluorescent marker and woodchuck hepatitis post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE). siRNAs for hsp25 were designed using the standard web based program (Invitrogen). The siRNAs were then converted into shRNA according to the web based program from Promega. The shRNAs contained restriction overhangs such as Mlu 1 and Cla 1 and standard hairpin loop structure TTCAAGAGA and a Pol III termination signal which consists of a run of at least 4Ts (TTTTTT). Oligos were synthesized at the minimal synthesis and purification scales. Then the complimentary oligos were annealed according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen, USA). To construct vector plasmids, the plasmid pLVTHM was digested with Mlu I and Cla I and ligated to an oligonucleotide pair containing Hsp25shRNA or controlshRNA carrying Mlu I and Cla I restriction overhangs and transformed into Max Stbl2 competent cells. The positive clones were identified by digesting the control pLVTHM vector and the vector containing Hsp25shRNA inserts using Mlu1 and Xba 1 enzymes. Positive clones were also identified by DNA sequencing.

Lentivirus Production and Transduction

See Supplementary Information section.

Hsp25 and Hsp27 Plasmids

See Supplementary Information section.

Animals and Tumor Challenge

See Supplementary Information section.

Live Animal Imaging

See Supplementary Information section.

Preparation of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMDM) and In Vitro Cross-Presentation Assay

See Supplementary Information section.

In Vivo Antibody Depletion Assay

See Supplementary Information section.

Isolation and Purification of CD8+ and CD8− T cells for the In Vivo Adoptive Transfer Assay

See Supplementary Information section.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

See Supplementary Information section.

Proteasome Activity Assay

See Supplementary Information section.

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons between groups, Dunn multiple comparison tests and Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used in this study (p values <0.001 were considered significant).

Results

Permanent and transient silencing of hsp25 or hsp27 gene results in effective down regulation of Hsp25 and Hsp27 protein expression in mouse and human breast cancer cells

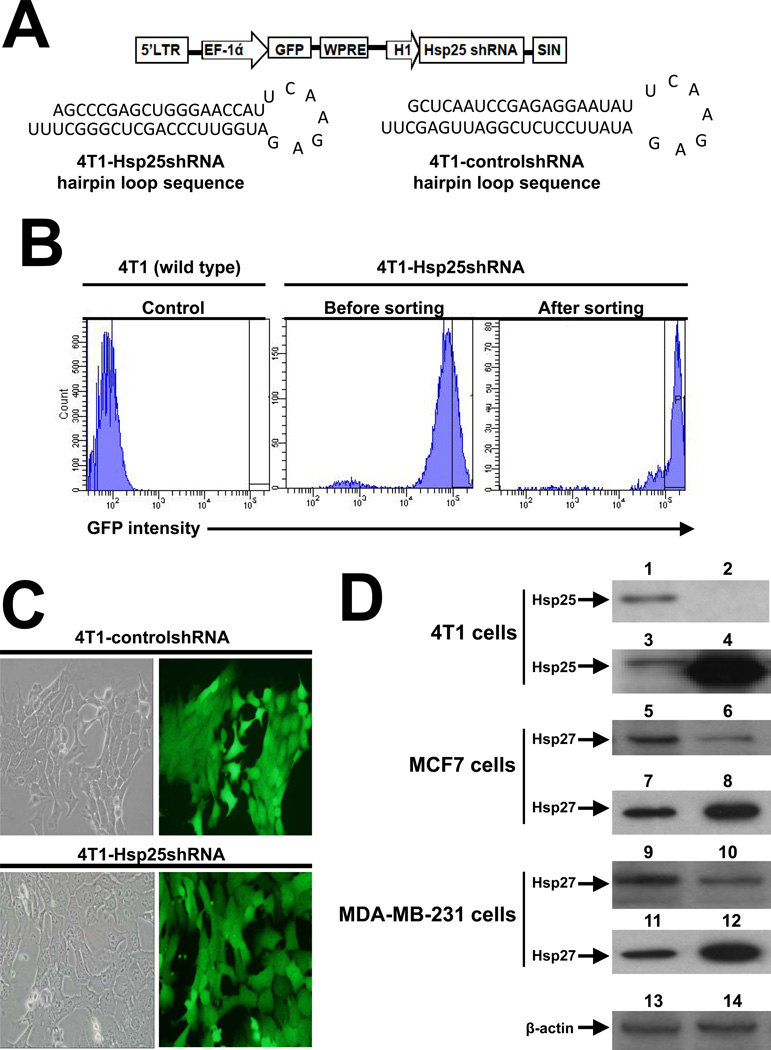

We used a lentivirus-based vector (pLVTHM) that expresses RNAi inducing the twenty-five kilo Dalton heat shock protein (Hsp25) shRNA (Hsp25shRNA) under the control of the H1 promoter (Fig 1A). This bicistronic vector was engineered to coexpress enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a reporter gene under the tight control of the elongation factor-1 alpha (EF-1α) promoter, permitting transduced/infected target cells to be tracked using in vivo imaging. Stable silencing of hsp25 gene expression in 4T1 tumor cells was achieved by subcloning the Hsp25shRNA cassette into pLVTHM, a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector using Mlu I and Cla I restriction sites (4T1-Hsp25shRNA hairpin loop sequence) (Fig 1A). We also constructed control/scrambled shRNA-containing lentiviral vector which does not have sequence homology to the mouse genome (4T1-controlshRNA hairpin loop sequence) (Fig 1A). These constructs were introduced into 293FT viral packaging cells to make lentivirus. The concentrated lentivirus preparation was used to infect target 4T1 breast adenocarcinoma cells. The resulting GFP expression was assessed 4 days post infection by flow cytometry and further enriched for only highly expressing GFP-positive cells. The resulting sorted 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells were 96.7% positive for GFP (Fig 1B). The high GFP expression exhibited by both 4T1-controlshRNA and Hsp25shRNA stable transfected cells remained high even after 6 weeks of culture (Fig 1C). We confirmed that high GFP expression in 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells corresponded to efficient silencing of Hsp25 protein expression consistently by >98% after 6–8 weeks in vitro cell culture, as compared to the expression of Hsp25 in 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Fig 1D). To negate the possibility that the stable transfection of only one cell line with Hsp25shRNA and selection after 6–8 weeks of culture might lead to the selection of a particular phenotype, additional experiments after short term treatment with siRNA was also performed. We demonstrated that transient transfection of human breast cancer cells MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 with Hsp27-siRNA resulted in effective suppression of Hsp27 protein expression as compared to cells transfected with control-siRNA (Ctrl-siRNA) (Fig 1D). Gain-of-function experiments using Hsp25-plasmids in 4T1 cells and Hsp27-plasmids in MCF7 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in the significant increase in Hsp25 and Hsp27 expression, as compared to control-plasmid (Ctrl-plasmid) (Fig 1D).

Figure 1. The expression of Hsp25 and Hsp27 in mouse and human breast cancer cells is effectively down regulated using Hsp25shRNA and Hsp25-siRNA respectively.

(A) HIV-based lentivirus construct pLVTHM was employed to infect 4T1 cells. Construct contains a 5’-long terminal repeats (LTR), gene encoding GFP as reporter and woodchuck hepatitis virus response element (WPRE) as enhancer of gene expression, placed under the tight control of elongation factor alpha (EF-1 ά) promoter. The Hsp25shRNA stem loop was placed downstream of the H1 promoter, and the self inactivating (SIN) element was placed downstream of the H1-Hsp25shRNA sequence (top panel). Schematic representation of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA and 4T1-controlshRNA hairpin sequences (bottom panel). (B) FACSAria generated histograms of lentivirus infected 4T1 cells showing a relative number of cells (ordinate) and GFP intensity (abscissa) of gated wild type 4T1 cells (left histogram), 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells before sorting (middle panel) and after cell sorting (right panel). Data are representative of three independently performed experiments with similar results. (C) Sorted 4T1-controlshRNA (top panels) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA (bottom panels) cells were imaged using a digital inverted fluorescent microscope. Micropictograms are phase contrast (left panels) and fluorescent images (right panels) and was obtained under 40× magnification. Data are representative of five independently performed experiments with similar results. (D) 4T1-controlshRNA (lanes 1, 13), 4T1-Hsp25shRNA (lanes 2, 14), or 4T1 cells transfected with Ctrl-plasmid (lane 3) and Hsp25-plasmid (lane 4) for 72 h at 37°C; or MCF7 cells transfected with Ctrl-siRNA (lane 5), Hsp27-siRNA (lane 6), Ctrl-plasmid (lane 7) and Hsp27-siRNA (lane 8) for 72 h at 37°C; or MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with Ctrl-siRNA (lane 9), Hsp27-siRNA (lane 10), Ctrl-plasmid (lane 11) and Hsp27-siRNA (lane 12) for 72 h at 37°C. Western blot analysis was performed on protein lysates and immunoblotted with anti-Hsp25 or anti-Hsp27 or β-actin (as loading control). Data are representative of three independently performed experiments with similar results.

Silencing Hsp25 increases cell death in tumor cells and increases the tumors ability to migrate in vitro

The uncontrollable growth of tumors and their ability to metastasize and invade distant organs is the hallmark of aggressive forms of cancer. We demonstrated that silencing Hsp25 protein expression dramatically increased cell death in tumor cells and the ability to the tumor to migrate in vitro. There were consistently less cells recovered from culture plates of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells as compared to 4T1-controlshRNA or wild type 4T1 (4T1-wt) cells (Fig S1A; left panel). Results of cell death measurements suggest the low cell count is due to a concomitant increase in the percentage of cell death in 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells as compared to 4T1-controlshRNA or 4T1-wt (Fig S1A; right panel). We demonstrated that Hsp25shRNA treatment adversely affects the directional cell migration of 4T1 cells in vitro, approximately to the same extent as serum starvation, as judged by the wound-healing experiment (Fig S1B). These results correlated well with the inability of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells to invade extracellular matrix in vitro as compared to 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Fig S1C).

We validated these data in experiments in which mouse and human breast cancer cells were transiently transfected with siRNA directed against Hsp25 or Hsp27, respectively. We demonstrated that silencing Hsp25/27 effectively suppressed the expression of proteins known to be important in cancer functions including; ABCB4 (growth, survival, proliferation), ENO1 (growth, differentiation, colony formation), HSP90AB1 (survival, migration, negative regulation of proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process), HSPA8 (apoptosis, ubiquitination, cell cycle progression, survival, cell viability), LDH (growth, transformation, proliferation), MCM3 (growth, migration), and MIF (proliferation, activation, migration). In addition, there was a concomitant decrease in the expression of proteins associated with cell movement (e.g., CAP (morphogenesis, migration, organization, morphology, depolymerization, elongation), EMTH (proliferation, quantity, development, activation), FLNA (cell spreading, motility, formation, migration), FLNB (migration, binding, anchoring), HSPD1 (chemotaxis, polarity, migration), MYH9 (adhesion, morphogenesis, movement, retraction, migration, formation), S100A6 (proliferation, survival, invasion, focus formation), TWIST1 (survival, migration, motility, adhesion, proliferation). On the other hand, there was an increase in the expression of proteins known to be associated with cell death (e.g., EEF2 (autophagy, cell death, apoptosis), FASN (apoptosis, G1 phase, G2 phase, senescence), GAPDH (apoptosis, cell death, caspase-independent cell death), HNRNPA1 (apoptosis, nuclear export, alternative splicing, stress response), KRT18 (apoptosis, cell death, collapse, fragmentation), YWHAE (apoptosis, cell cycle progression, mitosis, transmembrane potential), and antigen-presentation e.g., PSMB5 (degradation, proteolysis), TAP1 (autophosphorylation, antigen presentation), TAPBP (substrate selection, ubiquitination, selection, immune response) (Fig S1D). Together, these results indicate that silencing the expression of Hsp25/27 in breast adenocarcinoma tumors significantly interferes with its ability to survive and migrate in vitro.

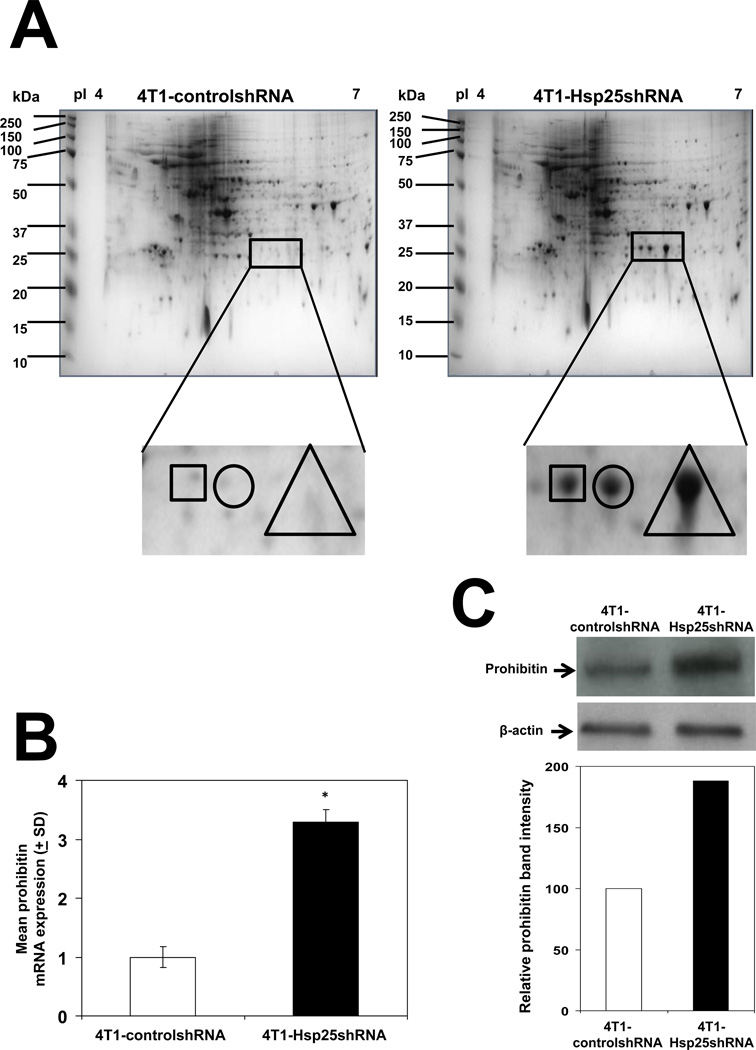

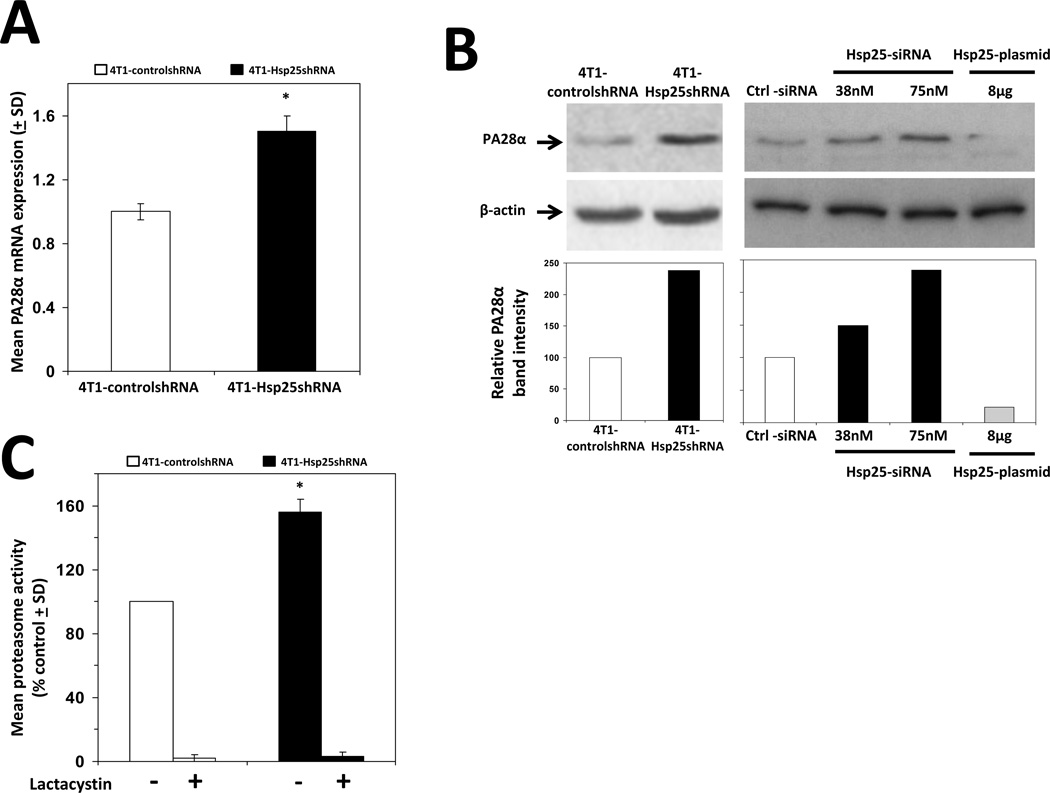

Hsp25/27 expression modulates proteasome activity in breast cancer cells

To obtain an integrative understanding of the effect of Hsp25 silencing on the global protein profile of 4T1 breast adenocarcinoma cells, we used 2D SDS-PAGE combined with LC-MS/MS techniques to compare the protein profiles between controlshRNA and Hsp25shRNA stably transfected 4T1 cells. Three unique spots were selected from 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (Fig 2A, right panel) which were absent in 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Fig 2A, left panel). Further characterization using LC-MS/MS and bioinformatics revealed that the unique proteins were NG,Ng-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 and prohibitin (Table I, square), PA28α, PA28γ subunits and mitochondrial ribosomal protein L46 (Table I, circle). Proteins expressed within the triangle could not be identified, possibly due to the highly glycosidic nature of the proteins (Table I, triangle). Due to the obvious relevance to tumor growth and metastasis, we chose to validate prohibitin and PA28α by real-time PCR and Western blot analysis. We demonstrated that silencing the hsp25 gene increased prohibitin mRNA expression by 3-fold (Fig 2B). mRNA expression levels correlated well with a 2.5-fold increase in prohibitin protein expression as judged by Western blot analysis (Fig 2C). Similar increases were observed for PA28α mRNA expression which was upregulated by 1.5-fold, as judged by real-time PCR (Fig 3A) and by 2-fold as judged by Western blot analysis (Fig 3B, left panel), as compared to respective controls. There was no significant alteration in the PA28γ subunit by measuring protein and RNA levels (data not shown). Transient transfection experiments demonstrated that treatment of 4T1 cells transfected with Hsp25-siRNA dose dependently increased PA28α expression (Fig 3B). Gain-of-function experiments to increase Hsp25 expression in 4T1 cells (using Hsp25-plasmids) demonstrated that the overexpression of Hsp25 dramatically suppresses PA28α expression (Fig 3B). To further validate the finding that silencing Hsp25 protein expression increases proteasome activity, we measured the chymotrypsin-like activity of 20S proteasome in 4T1-controlshRNA and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cell extracts. We demonstrated that 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells showed 50% greater proteasome activity than 4T1-controlshRNA tumor cells (Fig 3C). Since chymotrypsin-like activity of 20S proteasome uses Suc-LLVY-AMC as the substrate for proteasome activity measurement, we also measured trypsin-like and caspase-like proteasome activities in mouse and human breast cancer cells. We demonstrated that transient transfection using Hsp25-siRNA and Hsp27-siRNA effectively increases chymotrypsin-like, caspase-like and trypsin-like proteasome activities in 4T1, MCF7 and MDA-MD-231 cells, as compared to respective control-siRNA’s (Ctrl-siRNA) (Table II). The overexpression of Hsp25 and Hsp27 (using Hsp25-plasmid and Hsp27-plasmid, respectively) suppressed chymotrypsin-like, caspase-like and trypsin-like proteasome activities in 4T1, MCF7 and MDA-MD-231 cells, as compared to respective control-plasmids (Ctrl-plasmids) (Table II). Taken together, these results indicate that silencing of Hsp25 or Hsp27 enhances proteasome function via PA28α.

Figure 2. Silencing Hsp25 protein expression enhances prohibitin expression.

(A) Proteins from 4T1-controlshRNA cells (left panel) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (right panel) were focused over an IPG pH gradient of 4–7, separated on 8–16% polyacrylamide gradient SDS gel and stained with Bio-Safe Coomassie. Protein spot found within the square (□) represents Ng,Ng-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 and prohibitin; protein spot found within the circle (○) represents proteasome (prosome, macropain) 28 subunit alpha, PA28α and protein spot found within the triangle (Δ) represents undetectable proteins, as judged by mass spectrometry. Data is a representative experiment from three independently performed experiments with similar results. (B) 4T1-controlshRNA cells (open bar) and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (filled bars) were used to isolate total RNA and the relative prohibitin mRNA expression was measured using real-time PCR analysis. Data are the mean prohibitin mRNA expression (± SD) and are the sum of three independently performed experiments. *, p<0.001 vs 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Student’s t-test). (C) 4T1-controlshRNA cells (left lanes) and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (right lanes) were lysed, proteins extracted and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-prohibitin Mab (top panel) or β-actin (middle panel). The intensity of the bands were analyzed by densitometry with a video densitometer (Chemilmager™ 5500; Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) using the AAB software (American Applied Biology) (bottom panel). Bars represent the mean prohibitin protein expression from 4T1-controlshRNA cells (open bar) and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (filled bar) and is a representative experiment from three independently performed experiments with similar results.

Table I.

Identification of unique proteins in lentivirus-mediated Hsp25 knockdown in 4T1 cells using mass spectrometry.

| 2D-Gel spota |

Protein name | Database accession number |

Distinct summed MS/MS search score |

Protein MW (kDa)/pI |

% Amino acid coverage |

Number of peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square | NG, Ng-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 | 45476968 | 81.94 | 29,646/5.66 | 27 | 5 |

| Prohibitin | 74181431 | 65.46 | 29,850/5.40 | 21 | 5 | |

| Circle | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 28 subunit, alpha, PA28α | 12842740 | 168.86 | 28,640/5.48 | 50 | 11 |

| Proteasome activator subunit 3 | 6755214 | 80.66 | 29,506/5.69 | 34 | 6 | |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L46 | 12963643 | 62.77 | 32,131/6.93 | 16 | 5 | |

| Triangle | Not detectable | - | - | - | - | - |

4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells were run on 2D-SDS PAGE and protein spot was excised using Bio-Rad’s ExQuest spot cutter. Protein sample was digested in-gel, and peptides extracted and samples injected into a 1100 series HPLC-Chip cube MS interface, and Agilent 6300 series Ion Trap Chip-LC-MS/MS system (Agilent Technologies). The system is equipped with a HPLC-Chip (Agilent Technologies) that incorporates a 40nL enrichment column and a 43mm × 75mm analytical column packed with Zorbex 300SB-C18 5mm particles. Tandem MS spectra were searched against the National Center for Biological information nonredundant (NCBInr) mouse protein database, using Spectrum Mill Proteomics Work Bench for protein identification.

Figure 3. Silencing Hsp25/27 expression enhances proteasome activity and the expression of proteins associated with cell death and antigen presentation and suppresses the expression of proteins associated with cancer and cell movement.

(A) 4T1-controlshRNA cells (open bars) and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (filled bars) were used to isolate total RNA and the relative PA28α mRNA expression was measured using real-time PCR analysis. Bars are the mean PA28α mRNA expression (± SD) and are the sum of four independently performed experiments. *, p<0.001 vs 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Student’s t-test). (B) 4T1-controlshRNA cells (left panel, lane 1), 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (left panel, lane 2), 4T1 wild type cells were transfected with Ctrl-siRNA (right panel, lane 1), 38nM Hsp25-siRNA (right panel, lane 2), 75nM Hsp25-siRNA (right panel, lane 3), or 8µg Hsp25-plasmid (lane 4), for 72 h at 37°C. Cells were then lysed and proteins extracted and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-PA28α Mab (top panel) or β-actin (middle panel). The intensity of the bands were analyzed by densitometry with a video densitometer (Chemilmager™ 5500; Alpha Innotech) using the AAB software (bottom panel). Bars represent the relative PA28α band intensity and are a representative experiment from three independently performed experiments with similar results. (C) 20S proteasome activity was measured by incubation of cell extracts from 30µg 4T1-controlshRNA (open bars) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA (filled bars) for 90min with a fluorogenic substrate (Suc-LLVY-AMC) in the absence or presence of lactacystin (25µM). Free AMC fluorescence was measured by using a 380/460nm filter set in a fluorometer. Data are the mean proteasome activity (% control ± SD) and are the sum of three independently performed experiments. *, p<0.001 vs 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Student’s t-test).

Table II.

Modulation of proteasome activity in mouse and human breast cancer cells by silencing and overexpression of hsp25 and hsp27 genes, respectively.

| Cellsa | Treatmentb | Mean percentage proteasome activity as compared to respective control (% control ± SD)c |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totald | Caspase-likee | Trypsin-likef | ||

| 4T1 cells | Hsp25-siRNA | 52±5* | 25±4* | 22±7* |

| 4T1 cells | Hsp25-plasmid | −15±5* | −102±9* | ND |

| MDA-MB-231 cells | Hsp27-siRNA | 48±12* | 128±15* | 78±25* |

| MDA-MB-231 cells | Hsp27-plasmid | −21±5* | −75±8* | −53±6* |

| MCF7 cells | Hsp27-siRNA | 32±10* | 202±20* | 12±3* |

| MCF7 cells | Hsp27-plasmid | −15±5* | −66±10* | −32±9* |

Mouse (4T1) or human (MDA-MB-231 or MCF7) breast cancer cells (5,000 cells) were plated in 100µl complete culture media in a 96-well plate overnight in a 37°C incubator.

Cells were transfected with 75nM Hsp25-siRNA (Qiagen) or 15nm Hsp27-siRNA (Qiagen) or 8µg Hsp25/Hsp27-plasmids (Origene) using Lifofectamine RNAiMAX and Lifofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and incubated for a further 72 hours in a 37°C incubator.

The mean percentage proteasome activity as compared to respective control (% control ± SD) and is the sum of three independently performed experiments.

p<0.001 vs control (Student’s t-test).

Total proteasome activity was measured using the 20S proteasome activity assay kit (Millipore) against the fluorogenic proteasome substrate, SUc-LLVY-AMC according to the manufactures instructions (Millipore).

Caspase-like proteasome activity was measured using the Proteasome-Glo™ Caspase-like kit (Promega) according to the manufactures instructions (Promega). Luminescence was measured with a EG&G Berthold microplate luminometer.

Trypsin-like proteasome activity was measured using the Proteasome-Glo™ Trypsin-like kit (Promega, USA) according to the manufactures instructions (Promega). Luminescence was measured with a EG&G Berthold microplate luminometer.

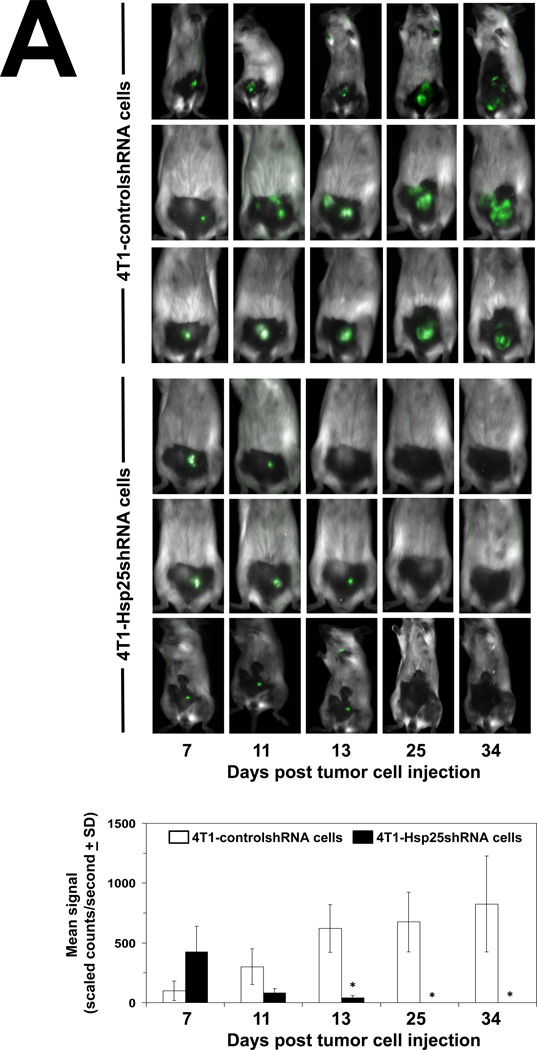

Silencing Hsp25/27 expression induces tumor regression and inhibits metastasis

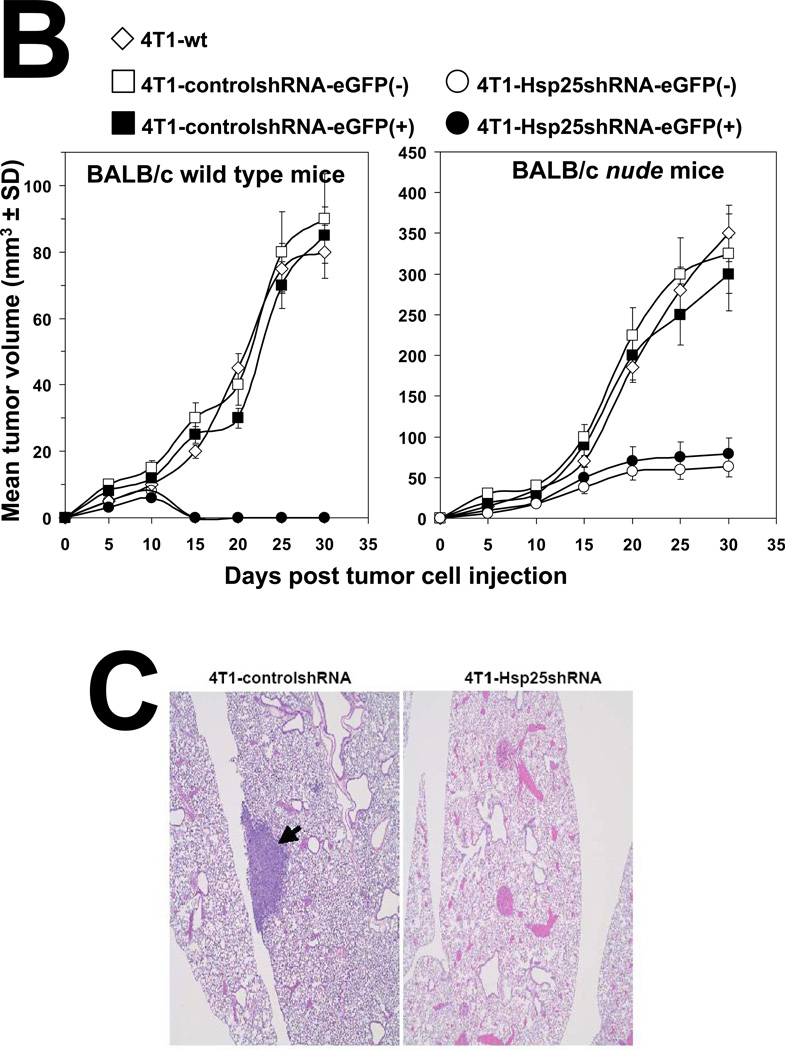

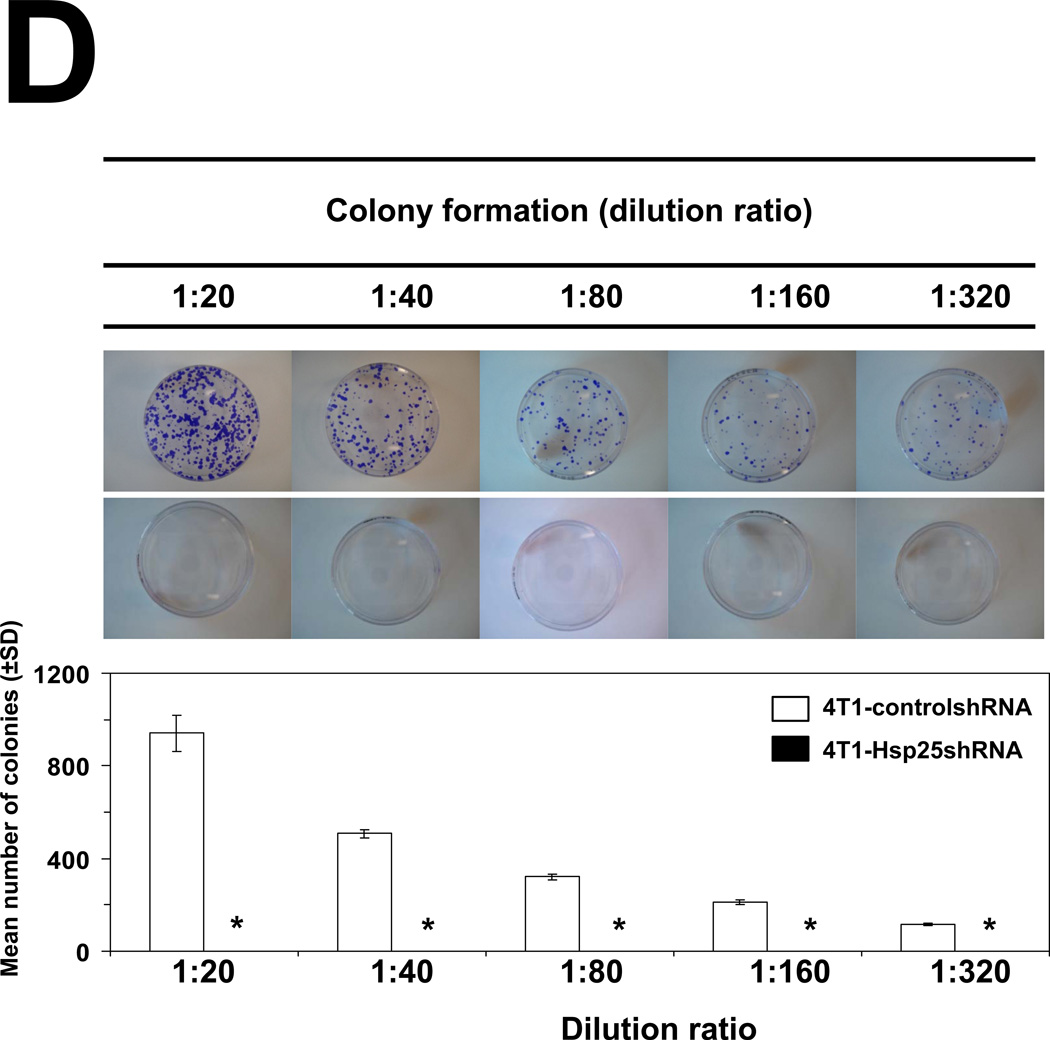

To determine the consequence of lentivirus-mediated hsp25 gene silencing in vivo, 4T1-controlshRNA and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the mammary pad of female BALB/c mice. As early as 7 days post tumor cells injection (TCI), tumors could be visualized growing in the mammary pad of all mice using the Maestro™ in vivo imaging system (CRI). We demonstrated that 13 days post TCI the GFP signal from 4T1-controlshRNA tumors were significantly higher than GFP signal from 4T1-Hsp25shRNA tumors (Fig 4A). Starting 7 days post TCI, there was a steady regression in GFP signal from 4T1-Hsp25shRNA tumors. By day 25 post TCI there was no detectable GFP signal in any mouse bearing 4T1-Hsp25shRNA tumors (Fig 4A). Efficient Hsp25 silencing (>95%) could still be demonstrated in 4T1-Hsp25shRNA tumors before they completely disappeared (data not shown). To negate the possibility that anti-tumor responses were directed against the GFP protein instead of unknown “tumor-associated antigens” that are better processed as a consequence of silencing Hsp25 expression in tumor cells, tumor growth experiments using eGFP positive(+) and negative(−) 4T1-Hsp25shRNA and 4T1-controlshRNA, and wild type 4T1 cells were performed. We demonstrated that eGFP did not significantly alter tumor growth curves of BALB/c wild type mice injected with eGFP positive(+) or negative(−) 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Fig 4B; left panel). Experiments performed in BALB/c nude mice further revealed that the tumor volume of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (with or without GFP) is significantly smaller than 4T1-controlshRNA (with or without GFP) or 4T1-wt cells (Fig 4B, right panel). An additional observation observed in the BALB/c nude mice experiments was that whereas the injected 4T1-controlshRNA and 4T1-wt cells rapidly metastasize to distant organs including lungs, liver and brain, injected 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells did not metastasize to these organs (data not shown), suggesting that although a competent immune system (possibly CD8+ CTL) may be one of the mechanisms associated with down regulation of Hsp25, there might be other mechanisms. At the end of the experiment (day 34 post TCI), gross pathology of multiple organs, including lungs, brain, bone and liver demonstrated an absence of tumor metastasis in mice injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA, but not 4T1-controlshRNA mice. H&E staining of lungs from mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA revealed micrometastasis in lung tissues (Fig 4C, left panel). In contrast, lungs of mice injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA had no visible micrometastasis (Fig 4C, right panel). To confirm that micrometastasis undetectable by light microscopy did not exist in 4T1-Hsp25shRNA injected mice; we performed colonogenisity assays on lung tissues in complete media containing 6-thioguanine. 4T1 breast adenocarcinoma cells are resistant to 6-thioguanine, however, all other contaminating cells will be destroyed. Mice injected with the 4T1-controlshRNA cells exhibited large numbers of colonies at all dilutions, reflecting robust metastasis of tumors to the lungs (Fig 4D). In contrast, no colonies were observed in dishes plated with lung tissue harvested from mice injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (Fig 4D). Taken together, these data suggest that permanent silencing of Hsp25 results in tumor regression and inhibition of metastasis in vivo.

Figure 4. Silencing hsp25 gene expression in 4T1 cells induces tumor regression and metastasis in vivo.

(A) 4T1-controlshRNA cells or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells were injected into the mammary pads of female BALB/c mice and tumor growth was monitored on specific days post tumor cell injection (TCI) using the Maestro™ in vivo imaging system (CRI). Data are fluorescent micropictograms of GFP-tagged tumors (green fluorescence) measured on various days post TCI (top panel). Bars represent the mean GFP signal/exposure (total signal scaled counts/seconds ± SD) from 4T1-controlshRNA cells (open bars) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (filled bars) and are the sum of three mice/group (n=3). *, p<0.001 vs 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Student’s t-test) (bottom panel). (B) 104 4T1-wt cells (open diamonds) or 4T1-controlshRNAe-GFP(−) cells (open squares) or 4T1-controlshRNA-e-GFP(+) cells (filled squares) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA-e-GFP(−) cells (open circles) or 4T1-Hsp25RNA-e-GFP(+) cells (filled circles) were injected into the mammary pads of female BALB/c wild type mice (left panel) or female BALB/c nude mice (right panel) and tumor growth was monitored on specific days post TCI using an electronic caliper. Data are mean tumor volume (mm3 ± SD) and are a representative experiment from two independently performed experiments (n=5). (C) H&E staining of lungs from mice implanted with 4T1-controlshRNA cells (left panel) or 4T1-Hsp25RNA cells (right panel) 34 days after TCI into the breast pad (arrow indicates lung micrometastasis). Data is a representative of four independently performed experiments with similar results. (D) Colony formation of tumors derived from lungs of mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA (top panels) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (middle panels) into the breast pad. Homogenized lung tissue was platted at different dilution ratios (1:20–1:320). Plates were stained and the mean number of colonies were counted after staining with crystal violet. Bars represent the mean number of colonies (± SD) from lungs of mice implanted with 4T1-controlshRNA cells (open bars) or 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (filled bars) and is a representative experiment from four independently performed experiments (bottom panel). *, p<0.001 vs 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Student’s t-test).

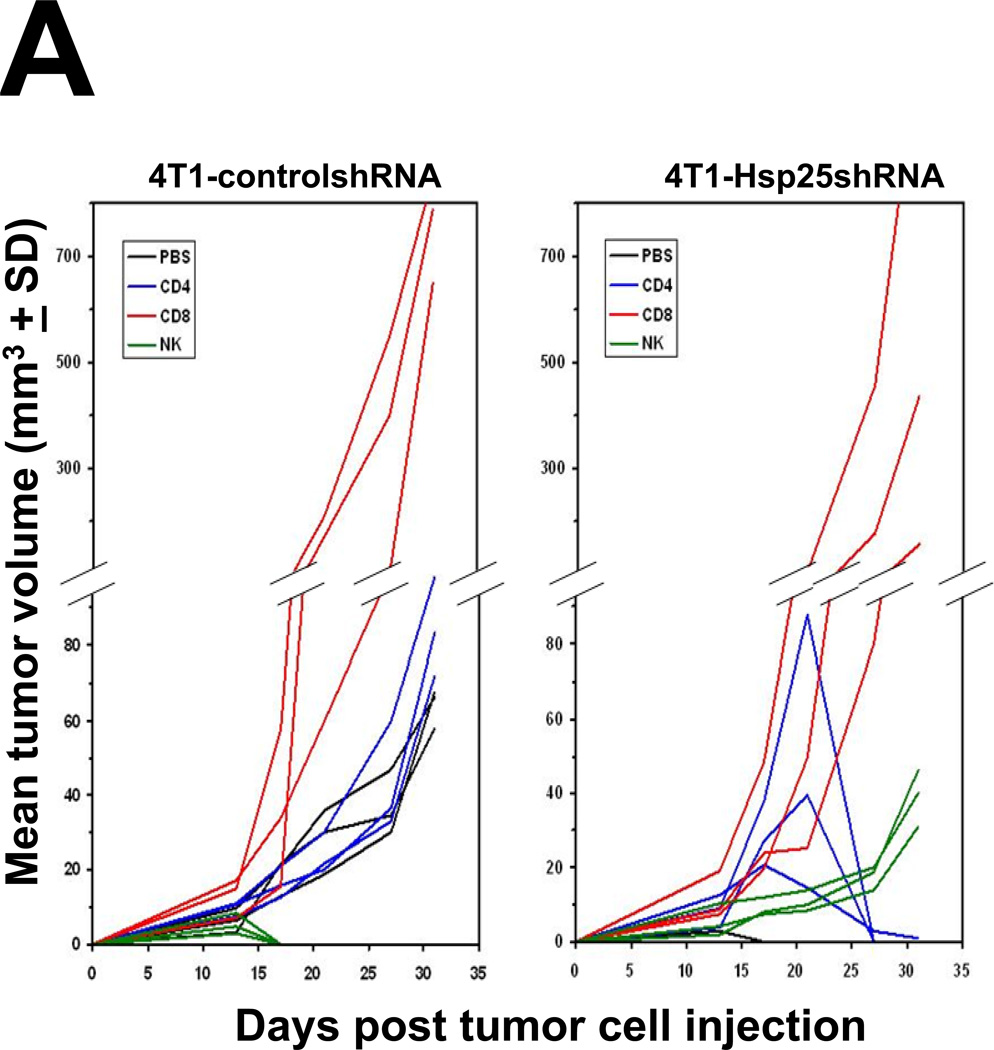

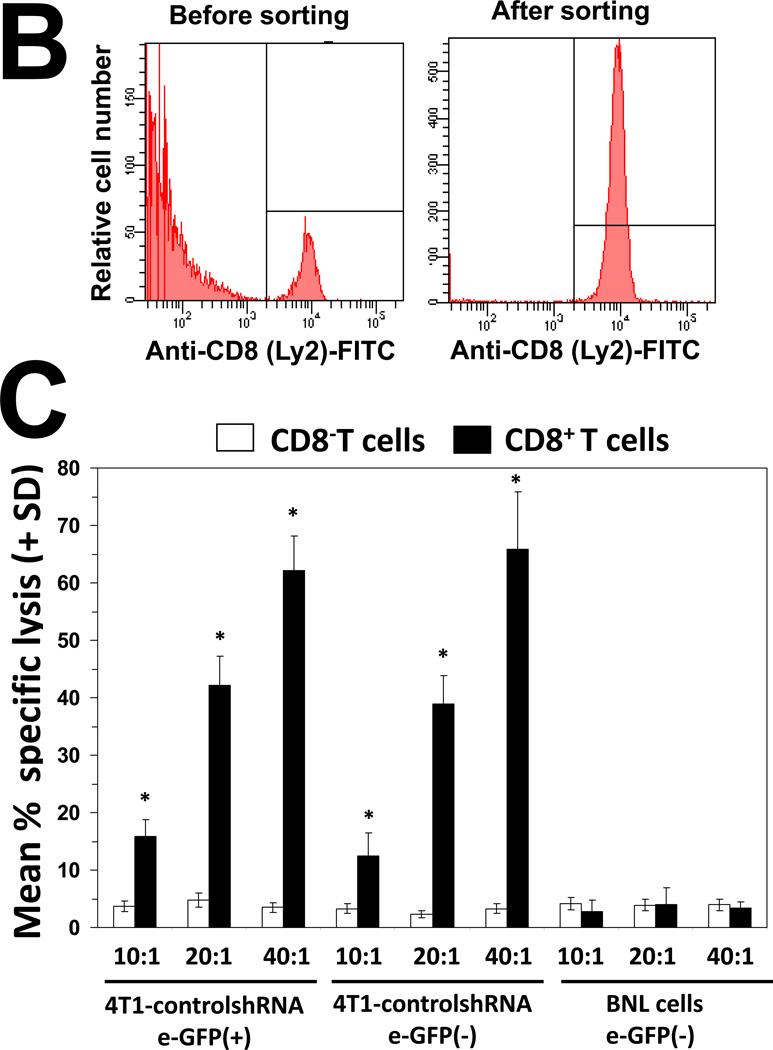

Silencing Hsp25/27 activates specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) killing functions and memory

To determine the nature of the cells responsible for tumor regression following silencing of Hsp25 expression in 4T1 breast adenocarcinoma cells, prior to TCI, we performed in vivo depletion of cells known to play an important role in tumor regression. Here, we demonstrated that in vivo depletion of CD8+ CTL prior to injection of 4T1-controlshRNA cells drastically increased tumor growth rate and by day 34 post TCI the size of the tumors were approximately 10 times larger than mice injected with PBS only (Fig 5A; left panel). The in vivo depletion of CD4+ T cells did not significantly alter tumor growth rate or tumor volume in mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Fig 5A; left panel). Unexpectedly, using similar mice the in vivo depletion of NK cells using the 5E6 monoclonal antibody induced complete tumor regression (Fig 5A; left panel). In mice injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells, no tumor growth was seen in any of the mice by the end of the experiment (Fig 5A; right panel). As expected, the in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells and NK cells prior to injection with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells resulted in tumor growth. Similar depletion of CD4+ T cells initially resulted in increased tumor growth, followed by tumor regression (Fig 5A; right panel). Interestingly, the in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells prior to injection with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells resulted in increased tumor growth (Fig 5A; right panel). Gross pathology of lung, brain and bone did not reveal any signs of metastasis to the lungs (data not shown). Similarly, injection of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells into the breast pad of BALB/c nude mice resulted in tumor growth without metastasis (data not shown).

Figure 5. Silencing hsp25/hsp27 gene expression augments CD8+ T lymphocyte-dependent tumor killing, recognition and memory responses.

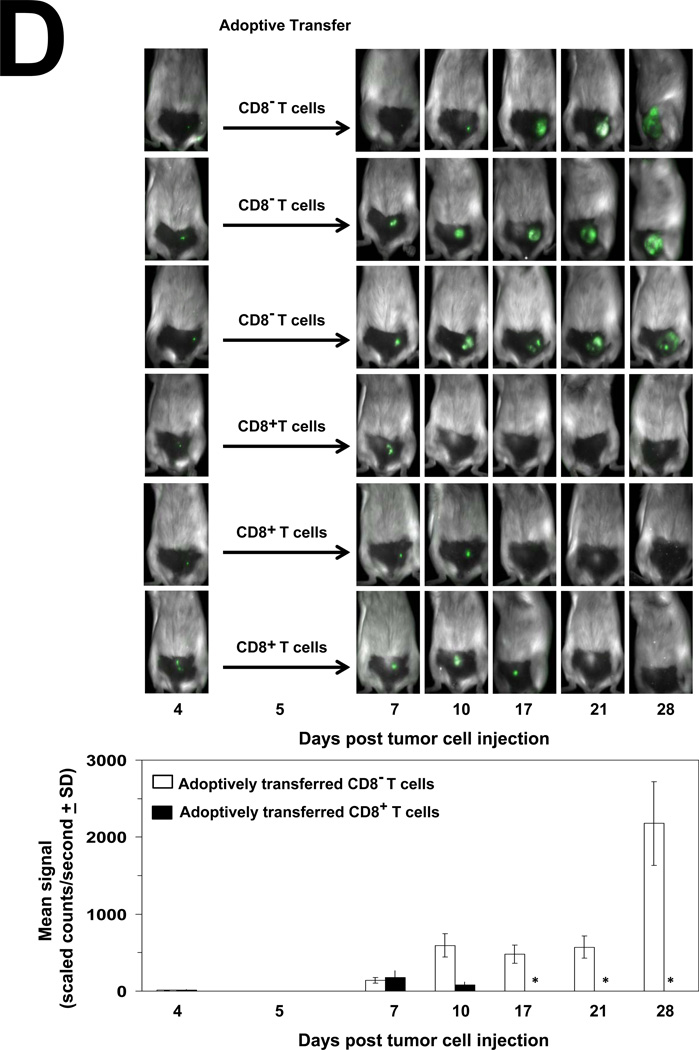

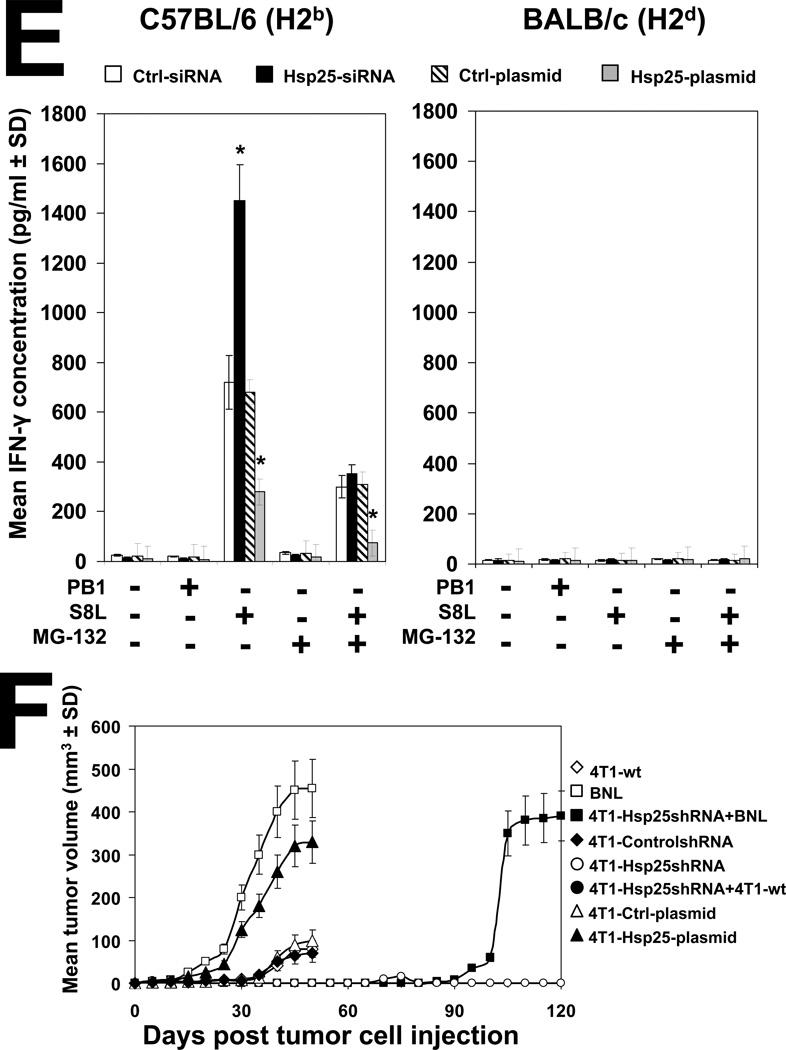

(A) Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were injected i.p., with PBS (black lines) or anti-CD4 (L3T4; blue lines), anti-CD8 (Ly-2; red lines) and anti-NK (5E6; green lines) 4 days before injection of 104 4T1-controlshRNA cells (left panels) or 104 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (right panels) into the abdominal mammary pads of mice every week. Data represent mean tumor volume (mm3 ± SD) and is representative of four independently performed experiments (n=3). (B) Splenocytes from female BALB/c mice were recovered and CD8+ T cells isolated using negative selection technique according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells (106) were stained with 0.5µg of anti-CD8a (Ly-2), washed and incubated with 0.6µg of the F(ab)2 anti-rat IgG-FITC (Caltag, Burlingame, CA, USA) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Samples were acquired in a FACScalibur cytometer and analyzed using the Cell Quest software (Beckton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). A total of 20,000 cells per condition were recorded and viable cells were defined according to the FSC and SSC pattern. Data are histograms for the relative number of cells expressing CD8a (Ly-2) and is a representative experiment from three independently performed experiments with similar results. (C) 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (104) were injected into mammary pads of 6–8 week-old female BALB/c mice. When tumors started regressing (at the end of two weeks) spleens were harvested and CD8− T cells (open bars) or CD8+ T cells (filled bars) were isolated using negative selection technique according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotech), and admixed with 4T1-controlshRNA-e-GFP(+) cells or 4T1-controlshRNA-e-GFP(−) cells or BNL cells which were seeded at various effector/target ratios (10:1, 20:1 and 40:1), in quintuplicate in 96-well tissue culture plates. Cytotoxicity was measured by lactate dehydrogenase-cytotoxicity assay kit II, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioVision). Bars are the mean percentage of specific lysis (± SD) and is the sum of four independently performed experiments. *, p<0.001 vs CD8− cells (Student’s t-test). (D) 4T1-controlshRNA cells (104)-tagged with GFP were injected into the mammary glands of female BALB/c mice on day 0. On day 5, mice were adoptively transferred with CD8− T cells (rows 1–3 from the top) or CD8+ T cells (rows 4–6 from the top) derived from the spleen of tumor-free female BALB/c mice previously injected with 104 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells. Tumor growth/regression was measured using Maestero™ in vivo imaging system Bars represent the mean GFP signal/exposure (total signal scaled counts/seconds ± SD) from animals adoptively transferred with CD8− T cells (open bars) or CD8+ T cells (filled bars) and is the sum of three mice/group (n=3). *, p<0.001 vs 4T1-controlshRNA cells (Student’s t-test) (bottom panel). (E) Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) were recovered from female C57BL/6 (H2b) mice (left panel) or female BALB/c (H2d) mice (right panel) and transfected with either control-siRNA (open bars) or Hsp25-siRNA (filled bars) or Ctrl-plasmid (hatched bars) or Hsp25-plasmid (grey bars) for 72 h at 37°C. Cells were then pulsed with 100ng/ml control peptide (PB1) or 100ng/ml OVA peptide (S8L) or 10µM MG-132 for a further 24 hours. Cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde and admixed with B3Z cells. Bars represent the mean IFN-γ concentration (pg/ml ± SD) and are the sum of four independently performed experiments. *, p<0.001 vs control-siRNA (Student’s t-test). (F) On day 0, female BALB/c mice were injected with either 105 BNL cells (open squares) or 104 4T1-wt cells (open diamonds) or 104 4T1-Ctrl-plasmid containing cells (open triangles) or 104 4T1-controlshRNA cells (open circles) or 104 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells (filled circles) or 104 4T1-Hsp25-plasmid containing cells that stably overexpress Hsp25 using lentivirus gene transfer vector (filled triangles). Tumor growth/regression was measured using an electronic caliper. Sixty-days post TCI mice previously injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells were re-challenged with either 104 4T1-wt cells (4T1-Hsp25shRNA + 4T1-wt; filled circles) or 105 BNL cells (4T1-Hsp25shRNA + BNL; filled squares) and tumor growth was monitored using an electronic caliper. Data are mean tumor volume (mm3 ± SD) and are the sum of two independently performed experiment (n=5).

To confirm that CD8+ T cells mediated the enhanced cytolytic effects after silencing Hsp25, reactive CD8+ T cells were harvested from the spleen of mice which had been injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells and were tumor-free (days 21–28 post TCI) and the specific T-cell cytotoxicity measured against 4T1-controlRNA target cells ex vivo. Extracted splenic CD8+ T cells were enriched using negative selection by magnetic beads and consistently exhibited >95% purity, as judged by flow cytometry (Fig 5B). Experiments were next performed to negate the possibility that the tumor-associated response was directed against GFP protein. We demonstrated that reactive CD8+ T cells, but not CD8− T cells (non-CD8+ T cells), effector cells harvested from the spleen of mice injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells, exhibited potent-specific lysis against 4T1-controlshRNA e-GFP positive and e-GFP negative targets with similar activity (Fig 5C). CD8+ cells did not exhibit significant lytic activity against BNL, which served as an irrelevant target (Fig 5C). As expected, both CD8+ and CD8− T cells from mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA cells did not mediate significant lysis above base-line levels against 4T1-controlshRNA targets. To determine whether 4T1-Hsp25shRNA reactive CD8+ T cells can rescue mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA cells, 4T1-Hsp25shRNA reactive CD8+ T cells were adoptively transferred into 4T1-controlshRNA tumor-bearing mice. As predicted, the adoptive transfer of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA reactive CD8+ T cells into 4T1-controlshRNA tumor-bearing mice induced significant tumor regression starting by day 17 post TCI and by day 28 there was no detectable tumor growth (Fig 5D). In contrast, 4T1-controlshRNA tumor-bearing mice adoptively transferred with CD8− T cell fraction were not protected and mice rapidly developed tumors (Fig 5D) and metastasis (data not shown).

To prove that the improvement in antigen presentation is due, in part, to silencing Hsp25 expression, we used the in vitro cross-presentation assay. BMDC were recovered from female C57BL/6 (H2b) and BALB/c (H2d) mice and treated with OVA during the culture process. BMDC were then transfected with either Hsp25-siRNA or negative control-siRNA and fixed with paraformaldehyde, and later admixed with S8L peptide-specific T cell hybridoma, B3Z cells. We demonstrated that B3Z cells released significantly more IFN-γ when admixed with C57BL/6 (H2b)-derived BMDC in which Hsp25 has been silenced (Hsp25-siRNA), as compared to control-siRNA treated BMDC (Fig 5E; left panel). In addition, we demonstrated that pre-treatment of both Hsp25-siRNA- and control-siRNA-treated BMDC with the specific proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, significantly reduced the concentration of released IFN-γ (Fig 5E; left panel). Finally, we demonstrated that BMDC recovered from BALB/c mice which express H2d did not release significant quantities of IFN-γ under similar conditions (Fig 5E; right panel). To prove that 4T1-Hsp25shRNA generates memory responses, tumor-free immunocompetent female BALB/c mice were re-challenged with wild type 4T1 (4T1-wt) or an irrelevant tumor, murine transformed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, BNL, 60 days post initial challenge with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA. We demonstrated that re-challenge of 4T1-wt cells does not result in tumor growth, which is similar to mice injected with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA alone (Fig 5F). However, re-challenge with BNL (after 4T1-Hsp25shRNA) resulted in tumor growth in a similar fashion to mice injected with BNL alone (Fig 5F).

Discussion

Mouse and human breast cancer cells express elevated levels of Hsp25 or Hsp27, respectively, which is effectively suppressed by permanently silencing Hsp25 or short term silencing of Hsp25 and Hsp27 protein expression (Fig 1D). This is important not only because elevated levels of Hsp27 in breast cancer gives rise to aggressive disease and poor prognosis (4), but also because elevated Hsp27 levels have been reported to confer tumor protection against Bortezomib-induced cell death (21). Bortezomib is characterized as a reversible proteasome inhibitor, with potent anti-cancer effects against multiple myeloma (22). Bortezomib was shown to effectively induce apoptotic cell death in DHL6 lymphoma cells (do not express significant Hsp27), but not DHL4 lymphoma cells (expressing high basal levels of Hsp27). Blocking the elevated Hsp27 expression in DHL4 lymphoma cells using antisense against Hsp27 restored sensitivity to Bortezomib. These authors concluded that combining agents that suppress Hsp27 expression might provide a therapeutic advantage to overcome tumors that might be resistant to Bortezomib treatment (21).

Our study demonstrates that silencing Hsp25/27 effectively suppresses proteins known to be important in cancer functions in cells (Fig S1D). Since the working hypothesis for this study is that high Hsp25/27 expression represses proteasome activity, therefore gain-of-function studies were also performed. Our results demonstrated that increasing Hsp25 or Hsp27 expression using Hsp25- or Hsp27-plasmids effectively increases Hsp25 or Hsp27 expression, respectively (Fig. 1D). The biological significance of increased Hsp25 or Hsp27 expression was a significant increase in dramatic inhibition of PA28α protein expression (Fig. 3B). We further demonstrated that silencing Hsp25 or Hsp27 concomitantly increases proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity (Fig 3C). Since chymotrypsin-like activity uses Suc-LLVY-AMC as the substrate for proteasome activity measurement, and since the same substrate can be digested by calpains, we also measured trypsin-like and caspase-like proteasome activities. We demonstrated that knockdown of Hsp25 or Hsp27 expression enhanced chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity, caspase-like proteasome activity and trypsin-like proteasome activity in mouse and human breast cancer cell lines, respectively (Table II). This is significant since Groettrup and colleagues reported that increased expression of PA28α results in marked enhancement of recognition by virus specific cytotoxic T cells (15). In addition, an essential role for PA28 was described in the melanoma cell line, Mel-18a. These authors demonstrated that recognition of TRP2-expressing melanoma cells by TRP2360–368-specific CTL directly correlated with the presence of PA28 and impaired epitope presentation on Mel-18a cells could be rescued by transfection of PA28 encoding plasmids (17). Here, we demonstrated that IFN-γ release from B3Z (a S8L peptide-specific T cell hybridoma) cells is greatly enhanced in OVA-treated BMDC transfected with Hsp25-siRNA and recovered from female C57BL/6 (H2b) mice, but not BALB/c (H2d) mice (Fig 5E). The role of the proteasome was further demonstrated in experiments in which pre-treatment with proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, dramatically inhibited IFN-γ release (Fig 5E). We further demonstrated that Hsp25-plasmid bearing 4T1 tumors grow approximately three-times larger than Ctrl-plasmid bearing 4T1 tumors or 4T1-wt tumors or 4T1-ControlshRNA tumors (Fig. 5F). Taken together, our data suggest that Hsp25/Hsp27 decreases ubiquitination proteasome degradation. This is in agreement with recent findings by other scientists (23–27). However, there are other authors who have previously demonstrated that Hsp27 enhances ubiquitination proteasomal degradation (28–31). The reason for this discrepancy is currently unknown. However, studies using antibodies to pull-down various components of the proteasome complex followed by mass spectrometry and bio-informatics analysis in response to high and low Hsp27 expression are currently underway in our lab (Nagaraja et al, manuscript in preparation) and should shed more light on this controversy.

Our additional working hypothesis, that high Hsp25 expression represses proteasome activity in turn down regulates peptide loading onto MHC class I molecules for effective recognition by CD8+ T cells, is substantiated by data presented in this study. The first suggestion for a role of CD8+ T cells was obtained in experiments in which BALB/c nude mice (which have defective CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) were injected with 4T1controlshRNA cells that grew approximately 3-times larger than similar cells injected into BALB/c wild type mice (Fig 4B). The role of CD8+ T cells was further substantiated in experiments in which the in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells using anti-CD8 (Ly-2) resulted in larger tumors in mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA and 4T1-Hsp25shRNA cells, as compared to animals injected with isotype control (Fig 5A). Interestingly, although tumors grew significantly larger in the breast pad of 4T1-Hsp25shRNA-bearing mice in the absence of CD8+ T cells there were no lung metastasis in these mice, as compared to 4T1-controlshRNA-bearing mice (data not shown). Although the possibility exists that the reason for the lack of pulmonary metastasis in 4T1-Hsp25shRNA-bearing mice in the absence of CD8+ T cells is only due to a decrease in primary tumor growth due to enhanced cell death (Fig S1A) and a decrease in proteins associated with cell death (Fig S1D), our in vitro data demonstrating that silencing Hsp25 also inhibits migration (Fig S1B), invasion (Fig S1C) and down regulated proteins involved in cell movement (Fig S1D), as well as, published data demonstrating that Hsp25 is critical for maintaining the integrity of cytoskeleton (32), suggest that in the absence of specific CD8+ CTL-mediated killing, the tumor is still incapable of leaving the primary tumor foci. Data demonstrating that depletion of NK cells in vivo resulted in enhanced anti-tumor killing and complete tumor regression was initially confounding (Fig 5A; green lines). However, further examination of the monoclonal antibody used to deplete NK cells in vivo revealed it to be the 5E6 Mab F(ab′)2 fragment, which reacts with Ly49C, a NK inhibitory receptor expressed on subsets of natural killer cells and NK1.1+ or DX5+ T cells in Balb/c mice (33). Studies by Koh and colleagues demonstrated that NK cell-mediated anti-tumor effector functions are increased against syngeneic tumors in vitro and in vivo by blockade of the Ly49C and Ly49I inhibitory receptors using the 5E6 monoclonal antibody (34). In addition, the ability of adoptively transferred 4T1-Hsp25shRNA reactive CD8+, but not CD8− T cells (non-CD8+ T cells) to rescue mice injected with 4T1-controlshRNA tumors (Fig 5D), which has been demonstrated to succumb from the tumor burden (Figs 4A, 4B, 5A), suggest that silencing Hsp25 improved the quality and/or quantity of peptides recognized by CD8+ T cells via a mechanism dependent on enhanced proteasome activity. Conclusive proof that silencing Hsp25 improves the quantity and/or quality of peptides presented onto MHC class I for specific CD8+ T lymphocyte recognition was obtained indirectly using the in vitro cross-presentation assay. Here, we demonstrated that silencing Hsp25 enhances recognition of B3Z (a S8L peptide-specific T cell hybridoma) cells for OVA-treated BMDC which have been transfected with Hsp25-siRNA and recovered from female C57BL/6 (H2b) mice, but not BALB/c (H2d) mice (Fig 5E).

The central role of the proteasome is demonstrated in experiments in which IFN-γ release in these cells was drastically blunted by pre-treatment with proteasome inhibitor, MG-132 (Fig 5E). The possibility that silencing Hsp25/27 improves antigen-presentation is further substantiated by data demonstrating that Hsp25-siRNA or Hsp27-siRNA treatment of breast cancer cells significantly increased genes important in antigen-presentation (Fig S1D). Our studies further demonstrated that silencing Hsp25/27 generates T cell memory responses. We showed that immunocompetent female BALB/c mice rendered tumor-free by injection with 4T1-Hsp25shRNA can be re-challenged with wild type 4T1 (4T1-wt) or 4T1controlshRNA or 4T1-Ctrl-plasmid-containing cells 60 days post initial challenge without tumor growth (Fig 5F). However, re-challenge with an irrelevant tumor, BNL cells (a murine transformed hepatocellular carcinoma cell line), resulted in tumor growth. The potent efficacious anti-tumor activities observed by silencing Hsp25 strongly suggest that other anti-tumor mechanisms have also been activated. This is supported by reports demonstrating that the human homologue of the mouse Hsp25, Hsp27 plays an essential role in, a) stabilizing actin filaments, a structural protein important for maintaining the integrity of cytoskeleton (32), b) cell cycle progression and proliferation (35), and c) apoptosis via caspase-3 activation (36, 37). Data from this manuscript suggest that enhanced tumor recognition by CD8+ CTL may be one of the mechanisms associated with down regulation of Hsp25/27, but does not rule out other pathways. In fact, the possibility exists that the down regulation of Hsp25/27 might activate CD8+ CTL-independent mechanisms associated with HSPs. Studies demonstrating that surface expression of Hsp70 in metastatic melanoma (38), acute myeloid leukemia (39), head and neck cancer (40) stimulates specific NK cell-mediated cytolytic functions, and the recent development of a Hsp70 peptide which has been shown to stimulate NK cell-mediated killing of leukemic blast cells (41, 42), and that NK cell-mediated targeting of membrane Hsp70 on tumors can be greatly enhanced after treatment with the cmHsp70.1 monoclonal antibody (43, 44), support the possibility that the down regulation of Hsp25/27 might such mechanisms.

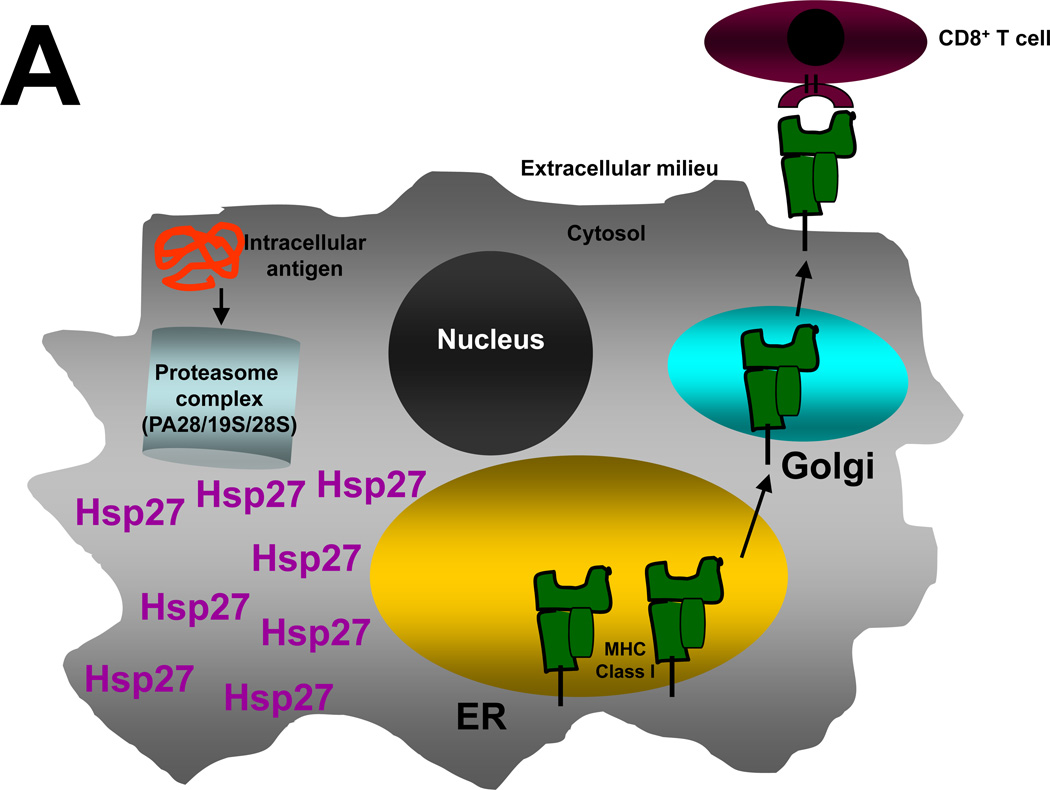

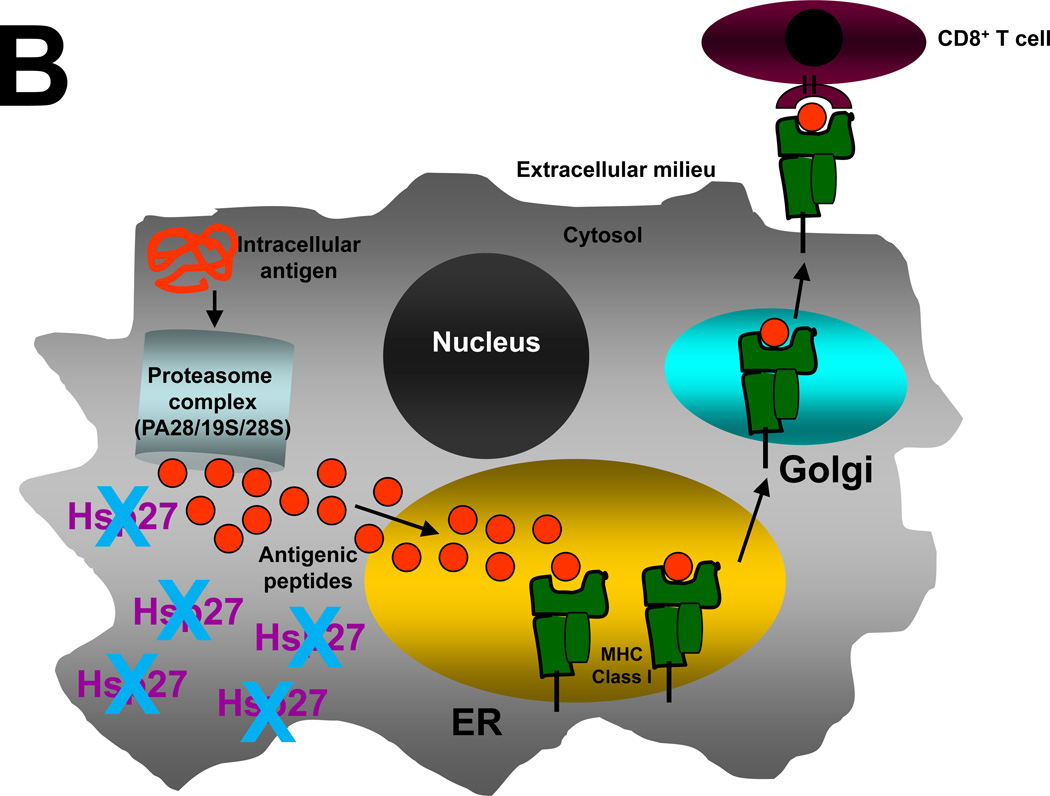

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that increasing proteasome activity of 4T1 breast adenocarcinoma cells by lentivirus-mediated hsp25 gene silencing or by the transient transfection of siRNA directed against Hsp25 in mice or Hsp27 in human breast cancer cell lines, increased specific CD8+ T lymphocyte tumor killing and enhanced memory responses. The hypothetical model of findings is summarized schematically in Figure 6. Our data have obvious clinical applications in light of recent successful clinical trials with the proteasome inhibitors. These clinical trials do not contradict our findings because Bortezomib resistance is observed in tumors with elevated Hsp27 expression (21). This would suggest that screening for patients on the basis of Hsp27 expression and proteasome activity might add benefit. In addition, this would suggest that combining agents that suppress Hsp27 expression might provide a therapeutic advantage for patients with Bortezomib-resistance. Clinical trials on the application of siRNA for the treatment of various diseases are underway and early results show it to be safe, with no patients experiencing any serious adverse events (45–47). However, there are current limitations to RNAi technology primarily in terms of possible “off-target” or nonspecific effects. Off-target effects occur when a siRNA is processed by the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) and down-regulates an unintended target(s) with similar sequence. An in-depth understanding of how siRNA is metabolized, and determining if intermediate metabolites are toxic or harmful, needs to be addressed. Efforts to recognize and circumvent off-target effects for enhanced target identification and to improve the therapeutic application of RNAi therapy in the clinic are now underway (reviewed in (48)).

Figure 6. Schematic representation of a hypothetical model by which elevated Hsp25/27 expression in tumors enhances repressed proteasome function, suppresses antigen presentation and inhibits tumor cell recognition by CD8+ CTL.

In all cells intracellular antigens or damaged proteins (red coiled lines) found in the cytosol enter the proteasome complex, which contains a PA28, 19S and 20S subunit (light blue cylinder). (A) In breast cancer cells high levels of Hsp27 inhibits normal proteasome function. This results in inefficient antigenic peptide loading onto MHC Class I molecules (green blocks) found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and inability of CD8+ CTL (maroon sphere) to recognize tumors. (B) Silencing Hsp27 allows antigenic peptides (red circles) to be efficiently transported into the ER, where they bind to MHC Class I molecule and are subsequently presented on the cell surface for antigen presentation via the Golgi apparatus. Once at the cell surface, the antigenic peptide-MHC Class I complex is scrutinized by CD8+ CTL (maroon sphere). Effective recognition of antigenic peptides by CD8+ CTL activates anti-tumor immune responses and results in efficient tumor killing and long lasting memory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Dider Trono (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing the lentivirus plasmids, Dr. Jahangir Kabir for helpful discussions, Dr. Hongying Zheng for expert flow cytometry assistance and the Scott & White Proteomics Core Facility. This work was supported in part by Scott & White Memorial Hospital and Clinic Research Advancement Awards (to G.M.N., and P.K.); the US National Institute of Health (RO1CA91889), Scott & White Memorial Hospital and Clinic, the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine (to A.A.), the Central Texas Veterans Health Administration and an Endowment from the Cain Foundation (to A.A.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Control

Ctrl

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- EF-lα

elongation factor-1 alpha

- ER

estrogen receptor

- Hsp25

twenty five-kilo Dalton heat shock protein

- hsp25

Hsp25 gene

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Mab

monoclonal antibody

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PA28α

proteasome activator subunit 28-alpha

- RNAi

RNA interference

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TAA peptides

tumor-associated antigenic peptides

- TCI

tumor cell injection

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Reference

- 1.Oesterreich S, Hickey E, Weber LA, Fuqua SA. Basal regulatory promoter elements of the hsp27 gene in human breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:155–163. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soldes OS, Kuick RD, Thompson IA, 2nd, Hughes SJ, Orringer MB, Iannettoni MD, et al. Differential expression of Hsp27 in normal oesophagus, Barrett's metaplasia and oesophageal adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:595–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budhram-Mahadeo VS, Heads RJ. Heat shock protein-27 (hsp27) in breast cancers: regulation of expression and function. In: Calderwood SK, Sherman MY, Ciocca DR, editors. Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2007. pp. 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Neill PA, Shaaban AM, West CR, Dodson A, Jarvis C, Moore P, et al. Increased risk of malignant progression in benign proliferating breast lesions defined by expression of heat shock protein 27. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:182–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rust W, Kingsley K, Petnicki T, Padmanabhan S, Carper SW, Plopper GE. Heat shock protein 27 plays two distinct roles in controlling human breast cancer cell migration on laminin-5. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 1999;1:196–202. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.1999.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciocca DR, Lo Castro G, Alonio LV, Cobo MF, Lotfi H, Teyssie A. Effect of human papillomavirus infection on estrogen receptor and heat shock protein hsp27 phenotype in human cervix and vagina. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1992;11:113–121. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oesterreich S, Weng CN, Qiu M, Hilsenbeck SG, Osborne CK, Fuqua SA. The small heat shock protein hsp27 is correlated with growth and drug resistance in human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4443–4448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto K, Okamoto A, Isonishi S, Ochiai K, Ohtake Y. Heat shock protein 27 was up-regulated in cisplatin resistant human ovarian tumor cell line and associated with the cisplatin resistance. Cancer Lett. 2001;168:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00532-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storm FK, Mahvi DM, Gilchrist KW. Heat shock protein 27 overexpression in breast cancer lymph node metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:570–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02306091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thor A, Benz C, Moore D, 2nd, Goldman E, Edgerton S, Landry J, et al. Stress response protein (srp-27) determination in primary human breast carcinomas: clinical, histologic, and prognostic correlations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:170–178. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vargas-Roig LM, Gago FE, Tello O, Aznar JC, Ciocca DR. Heat shock protein expression and drug resistance in breast cancer patients treated with induction chemotherapy. International Journal of Cancer. 1998;79:468–475. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981023)79:5<468::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sondel PM, Rakhmilevich AL, de Jong JLO, Hank JA. Cellular immunity and cytokines. In: Mendelsohn J, Howley PM, Israel MA, Liotta LA, editors. The Molecular Basis of Cancer. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2001. pp. 535–571. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kloetzel PM. The proteasome and MHC class I antigen processing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groettrup M, Soza A, Eggers M, Kuehn L, Dick TP, Schild H, et al. A role for the proteasome regulator PA28alpha in antigen presentation. Nature. 1996;381:166–168. doi: 10.1038/381166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dick TP, Ruppert T, Groettrup M, Kloetzel PM, Kuehn L, Koszinowski UH, et al. Coordinated dual cleavages induced by the proteasome regulator PA28 lead to dominant MHC ligands. Cell. 1996;86:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Y, Sijts AJ, Song M, Janek K, Nussbaum AK, Kral S, et al. Expression of the proteasome activator PA28 rescues the presentation of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope on melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2875–2882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stohwasser R, Salzmann U, Giesebrecht J, Kloetzel PM, Holzhutter HG. Kinetic evidences for facilitation of peptide channelling by the proteasome activator PA28. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6221–6230. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitby FG, Masters EI, Kramer L, Knowlton JR, Yao Y, Wang CC, et al. Structural basis for the activation of 20S proteasomes by 11S regulators. Nature. 2000;408:115–120. doi: 10.1038/35040607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pamer E, Cresswell P. Mechanisms of MHC class I--restricted antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:323–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan D, Li G, Shringarpure R, Podar K, Ohtake Y, Hideshima T, et al. Blockade of Hsp27 overcomes Bortezomib/proteasome inhibitor PS-341 resistance in lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6174–6177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, Chauhan D, Fanourakis G, Gu X, et al. Molecular sequelae of proteasome inhibition in human multiple myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14374–14379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202445099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrieu C, Taieb D, Baylot V, Ettinger S, Soubeyran P, De-Thonel A, et al. Heat shock protein 27 confers resistance to androgen ablation and chemotherapy in prostate cancer cells through eIF4E. Oncogene. 2010;29:1883–1896. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trott D, McManus CA, Martin JL, Brennan B, Dunn MJ, Rose ML. Effect of phosphorylated hsp27 on proliferation of human endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Proteomics. 2009;9:3383–3394. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapinska AM, Gratacos FM, Krause CD, Hernandez K, Jensen AG, Bradley JJ, et al. Chaperone Hsp27 modulates AUF1 proteolysis and AU-rich element-mediated mRNA degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1419–1431. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00907-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang E, Heo KS, Woo CH, Lee H, Le NT, Thomas TN, et al. MK2 SUMOylation regulates actin filament remodeling and subsequent migration in endothelial cells by inhibiting MK2 kinase and HSP27 phosphorylation. Blood. 2011;117:2527–2537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Thonel A, Vandekerckhove J, Lanneau D, Selvakumar S, Courtois G, Hazoume A, et al. HSP27 controls GATA-1 protein level during erythroid cell differentiation. Blood. 2010;116:85–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-241778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parcellier A, Brunet M, Schmitt E, Col E, Didelot C, Hammann A, et al. HSP27 favors ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of p27Kip1 and helps S-phase re-entry in stressed cells. Faseb J. 2006;20:1179–1181. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4184fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parcellier A, Schmitt E, Gurbuxani S, Seigneurin-Berny D, Pance A, Chantome A, et al. HSP27 is a ubiquitin-binding protein involved in I-kappaBalpha proteasomal degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5790–5802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5790-5802.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friant S, Meier KD, Riezman H. Increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation can replace the essential requirement for heat shock protein induction. Embo J. 2003;22:3783–3791. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.den Engelsman J, Keijsers V, de Jong WW, Boelens WC. The small heat-shock protein alpha B-crystallin promotes FBX4-dependent ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4699–4704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guay J, Lambert H, Gingras-Breton G, Lavoie JN, Huot J, Landry J. Regulation of actin filament dynamics by p38 map kinase-mediated phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 3):357–368. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu YY, George T, Dorfman JR, Roland J, Kumar V, Bennett M. The role of Ly49A and 5E6(Ly49C) molecules in hybrid resistance mediated by murine natural killer cells against normal T cell blasts. Immunity. 1996;4:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh CY, Blazar BR, George T, Welniak LA, Capitini CM, Raziuddin A, et al. Augmentation of antitumor effects by NK cell inhibitory receptor blockade in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2001;97:3132–3137. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farooqui-Kabir SR, Budhram-Mahadeo V, Lewis H, Latchman DS, Marber MS, Heads RJ. Regulation of Hsp27 expression and cell survival by the POU transcription factor Brn3a. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:1242–1244. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rocchi P, Beraldi E, Ettinger S, Fazli L, Vessella RL, Nelson C, et al. Increased Hsp27 after androgen ablation facilitates androgen-independent progression in prostate cancer via signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-mediated suppression of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11083–11093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rocchi P, Jugpal P, So A, Sinneman S, Ettinger S, Fazli L, et al. Small interference RNA targeting heat-shock protein 27 inhibits the growth of prostatic cell lines and induces apoptosis via caspase-3 activation in vitro. BJU Int. 2006;98:1082–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farkas B, Hantschel M, Magyarlaki M, Becker B, Scherer K, Landthaler M, et al. Heat shock protein 70 membrane expression and melanoma-associated marker phenotype in primary and metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Research. 2003;13:147–152. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gehrmann M, Schmetzer H, Eissner G, Haferlach T, Hiddemann W, Multhoff G. Membrane-bound heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) in acute myeloid leukemia: a tumor specific recognition structure for the cytolytic activity of autologous NK cells. Haematologica. 2003;88:474–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleinjung T, Arndt O, Feldmann HJ, Bockmuhl U, Gehrmann M, Zilch T, et al. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) membrane expression on head-and-neck cancer biopsy-a target for natural killer (NK) cells. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2003;57:820–826. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross C, Holler E, Stangl S, Dickinson A, Pockley AG, Asea AA, et al. An Hsp70 peptide initiates NK cell killing of leukemic blasts after stem cell transplantation. Leuk Res. 2008;32:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stangl S, Gross C, Pockley AG, Asea AA, Multhoff G. Influence of Hsp70 and HLA-E on the killing of leukemic blasts by cytokine/Hsp70 peptide-activated human natural killer (NK) cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2008;13:221–230. doi: 10.1007/s12192-007-0008-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stangl S, Gehrmann M, Dressel R, Alves F, Dullin C, Themelis G, et al. In vivo imaging of CT26 mouse tumours by using cmHsp70.1 monoclonal antibody. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:874–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stangl S, Gehrmann M, Riegger J, Kuhs K, Riederer I, Sievert W, et al. Targeting membrane heat-shock protein 70 (Hsp70) on tumors by cmHsp70.1 antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:733–738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016065108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeVincenzo J, Lambkin-Williams R, Wilkinson T, Cehelsky J, Nochur S, Walsh E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of an RNAi-based therapy directed against respiratory syncytial virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8800–8805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912186107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leachman SA, Hickerson RP, Schwartz ME, Bullough EE, Hutcherson SL, Boucher KM, et al. First-in-human mutation-targeted siRNA phase Ib trial of an inherited skin disorder. Mol Ther. 2010;18:442–446. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaiser PK, Symons RC, Shah SM, Quinlan EJ, Tabandeh H, Do DV, et al. RNAi-based treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration by Sirna-027. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.02.006. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.