Abstract

BACKGROUND:

This trial study aimed to assess the effects of adenoidectomy on the markers of endothelial function and inflammation in normal-weight and overweight prepubescent children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

METHODS:

This trial study was conducted in Isfahan, Iran in 2009. The study population was comprised of 90 prepubescent children (45 normal-weight and 45 overweight children), aged between 4-10 years old, who volunteered for adenoidectomy and had OSA documented by validated questionnaire. The assessment included filling questionnaire, physical examination, and laboratory tests; it was conducted before the surgery and was repeated two weeks and six months after the surgery.

RESULTS:

Out of the 90 children evaluated, 83 completed the 2-week evaluation and 72 patients continued with the study for the 6-month follow up. Markers of endothelial function, i.e., serum adhesion molecules including endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule (E-selectin), intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), and the markers of inflammation, i.e., interleukin-6, and high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) decreased significantly in both normal-weight and overweight children after both two weeks and six months. After six months, the total and LDL-cholesterol showed a significant decrease in the overweight children.

CONCLUSIONS:

The findings of the study demonstrated that irrespective of the weight status, children with OSA had increased levels of the endothelial function and inflammation markers, which improved after OSA treatment by adenoidectomy. This might be a form of confirmatory evidence on the onset of atherogenesis from the early stages of the life, and the role of inflammation in the process. The reversibility of endothelial dysfunction after improvement of OSA underscores the importance of primordial and primary prevention of chronic diseases from the early stages of the life.

KEYWORDS: Sleep, Endothelial Function, Inflammation, Child, Prevention

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a prevalent medical condition, with an estimated prevalence of 2–3% in children; it is characterized by repetitive upper airway obstruction, resulting in continued breathing effort with diminished airflow.1–4

Although the main symptom of OSA is daytime hypersomnolence, patients with OSA are at a higher risk of metabolic disorders5,6 and the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality.7 It was previously assumed that these complications are related to obesity; however, the recent data suggests that OSA may have an independent association with cardio metabolic risk factors.8

There is a growing body of evidence on the interaction of OSA with the metabolic dysfunction, which is known as a risk factor for CVD in adults.8,9 Although it is well-documented that CVDs origin from the early stages of life and the CVD risk factors tend to track from childhood into the adulthood,10–12 limited experience exist on the association of OSA and cardio metabolic risk factors in the pediatric age group.

Improvement of OSA by adenoidectomy might have beneficial effects on metabolic dysfunction. The current trial aimed to assess the effects of adenoidectomy on the markers of endothelial function and inflammation in the normal-weight and overweight prepubescent children with OSA.

Methods

This clinical trial study was conducted among children who volunteered for adenoidectomy in Isfahan, the second large city in Iran from May to December 2009.

Participants

The study population were comprised of 90 prepubescent children (45 normal-weight and 45 overweight children), aged between 4-10 years old, who volunteered for adenoidectomy and had OSA documented by a validated questionnaire. Those children with syndromic obesity, endocrine disorders, any physical disability, and or history of any chronic medication use were not included in the trial. Two groups of normal-weight and overweight children13 were selected consecutively among the children who were referred for adenoidectomy.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. After providing detailed oral information to the children and their parents, written informed consents were obtained from the parents of eligible children.

OSA was documented by a widely used and validated questionnaire.14 The questionnaire was extended with questions concerning (i) Child's demographic data (i.e., gender, age, height, weight, household smoking, and parental education), (ii) Daytime behavior (e.g., hyperactive-inattentive behavior and tiredness), (iii) Frequent sleep problems (i.e., sleep-onset delays, enuresis, night waking, nightmares, and sleep walking), and (iv) the Current health status (e.g., frequency of upper respiratory tract infections).

Except for the first three items, which were on a 4-point rating scale: ‘Never’, ‘occasionally’, ‘frequently’, and ‘always’, most questions were to be answered on a 5-point rating scale (‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘occasionally’, ‘frequently’, ‘almost always’).

Anthropometric Measurement and Clinical Examination

All measurements were made by a trained team of general physicians and nurses under supervision of the same pediatrician, using calibrated instruments and standard protocols. The weight (Wt) and the height (Ht) were measured by calibrated scale and Stadiometer (Seca, Japan) with participants lightly clothed and barefooted nearest to 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed as Wt (kg) divided by Ht (m) squared. The BMI percentiles was compared to the BMI charts of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the BMI levels corresponding the age and gender-specific 5th-85th percentile were considered as normal-weight, and the BMI ≥ 85th percentile was considered as overweight.13 The blood pressure (BP) was measured using mercury sphygmomanometer under the standard protocol. The readings at the first and the fifth Korotkoff phase were taken as systolic and diastolic BP (SBP and DBP), respectively. The average of the two BP measurements was recorded.15

Biochemical measurements

Participants were asked to fast for 12 hours before the screening and compliance with fasting was determined by interview on the morning of examination. While one of the parents accompanied the child, fasting blood samples were taken from the ante-cubital vein, and within 30 minutes after venipuncture were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm. The fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides (TG), and high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) were measured using auto-analyzer. HDL-C level was determined after dextran sulphate-magnesium chloride precipitation of non-HDL-C.16 Serum adhesion molecules, i.e., intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule (E-selectin), as well as interleukin-6 (IL-6) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method using standard kits (Bender Med Systems, GmbH, Vienna, Austria).

Comparisons

All the baseline assessments including filling the questionnaire, physical examination and laboratory tests were repeated within two weeks and six months after adenoidectomy to determine the short-term and long-term changes in both groups after the OSA treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The data was stored in a computer database. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software (version 15.00, SPSS, Chicago, IL.). The descriptive data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The normality of the distribution of variables was verified by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The time trend of the changes within and between the groups was analyzed by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc tests. The significance level was considered at p < 0.05.

Results

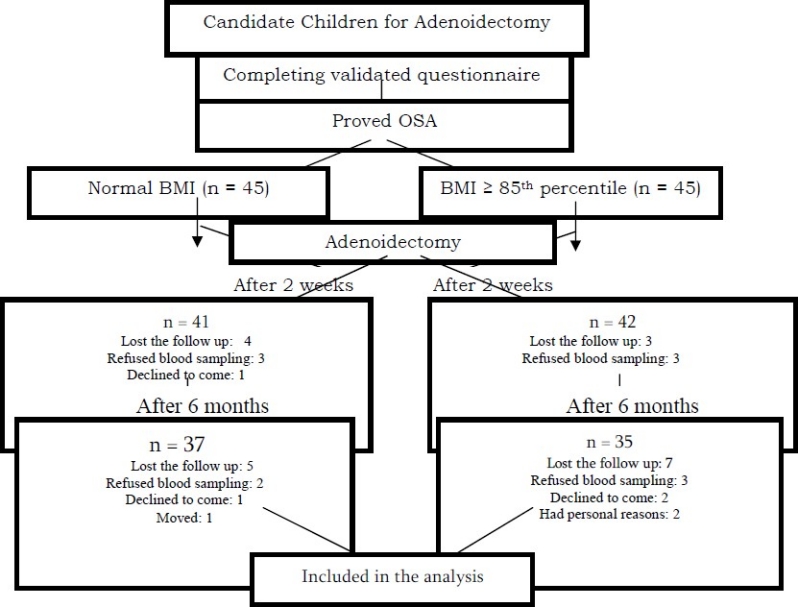

As presented in Figure 1, among the 90 potential candidates who initially agreed to participate in the study, there were 41 children in group A (normal BMI) and 42 children in group B (BMI ≥ 85th percentile) after two weeks follow up, because some participants refused the blood sampling or declined to come for the follow up visits. At the 6-month follow up, the number of participants reduced to 37 in group A and 35 in group B. Based on the data obtained from the questionnaires, the OSA symptoms disappeared in both study groups.

Figure 1.

Participants’ retention vs. attrition

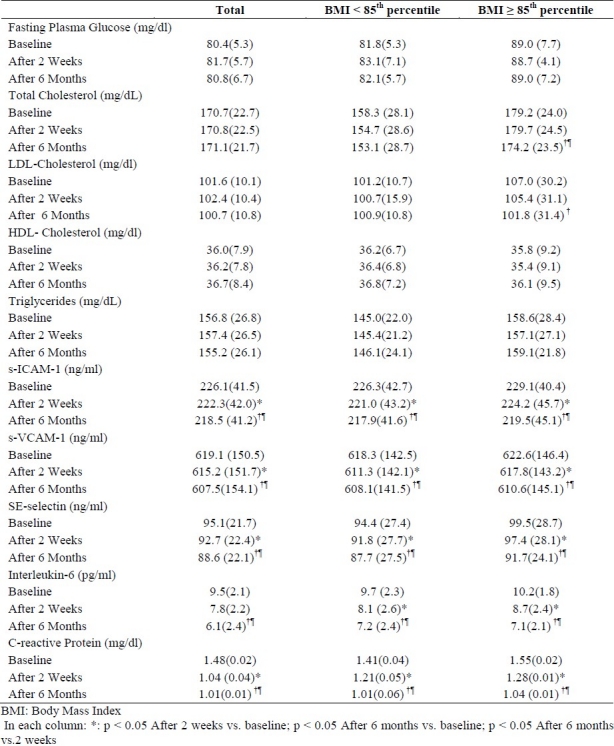

Table 1 shows the metabolic and inflammatory changes in the normal-weight and overweight children before the operation and two weeks and six months after undergoing the adenoidectomy.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) of variables studied from baseline to 2 weeks and 6 months after adenoidectomy in normal-weight and overweight children

After six months, the total and LDL-cholesterol had significant decreases in over-weight children. The most remarkable changes were the decline in the levels of markers of endothelial function and inflammation, i.e., ICAM-I, VCAM-I, E-Selectin, IL-6, and hs-CRP, which decreased in both normal-weight and overweight participants after both two weeks and six months.

Discussion

This trial revealed an independent association between OSA and the level of endothelial function and inflammation markers, which decreased after adenoidectomy in normal-weight and overweight children. These changes occurred in absence of the changes in most conventional cardio metabolic risk factors.

The relationship of the inflammatory processes with the progress of atherosclerosis provides important links between underlying mechanisms of atherogenesis and CVD risk factors. Therefore, the inflammatory biomarkers are considered as potential predictors of the present and future risk of CVD. Up-regulation of endothelial adhesion molecules, i.e., endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule (E-selectin), intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), might have a crucial role in the earliest phases of atherosclerosis.17,18 Concentrations of inflammation markers and soluble adhesion molecules were found to be higher in obese children than those in lean children.19,20 These findings suggest early stages of endothelial dysfunction in children.

Atherosclerosis starts from the fetal life and its natural course consists of interrelations between the traditional risk factors and inflammatory and endothelial biomarkers. The features of chronic inflammation can be detected in fatty streaks, i.e., the first stage of atherosclerotic lesions.21 Childhood obesity has become a health issue problem among Iranian children, even in those as young as six years of age,22 and considering that many studies have documented the presence of atherosclerosis and inflammation surrogate markers as well as structural arterial changes among obese children,23–26 the importance of the prevention and controlling this type of nutritional disorder is underscored.

The findings of the current study suggested the independent association of OSA with the inflammation marker levels in the normal-weight and overweight children. Concentration of these markers declined shortly after the OSA treatment. Children with OSA, experience a combination of oxidative stress, inflammation, autonomic activation, and disruption of sleep homeostasis.27 The independent association of the OSA with markers of inflammation in the normal-weight and over-weight prepubescent children documented in the current trial is consistent with the independent association of the OSA with the metabolic syndrome in adults.28

Our findings are in line with the findings of a previous study conducted in the normal-weight children with OSA who underwent adenoidectomy, which reported a decrease in the endothelial function markers levels.29

It was also found that children with resolution of OSA abnormalities experienced a change in the total and LDL-cholesterol levels, supporting the hypothesis that reversal of OSA may also reverse the progression of dyslipidemia over time, which is an important implication for the future CVD risk.30

The main limitation of this study was the questionnaire-based diagnosis of OSA, because of the high costs of polysomnography (PSG). The main novelty of the study is the measurement of markers such as adhesion molecules that have not been previously examined in trials among children with OSA.

Conclusion

The findings of the study demonstrated that irrespective of the weight status, children with OSA had increased the endothelial function and inflammation markers level, which improved after the OSA treatment by adenoidectomy. This might be complementary evidence on the onset of atherogenesis from the early stages of life and the role of inflammation in this process. The reversibility of endothelial dysfunction after the OSA treatment underscores the importance of the primordial and primary prevention of chronic diseases from the early stages of life. Future longitudinal studies documenting OSA by polysomnography (PSG) are recommended.

Authors’ Contributions

RK participated in the design and conducting the study, drafted and edited the manuscript; NN participated in the design and conducting the study; AO participated in the design and conducting the study; BA participated in the design and conducting the study; PP helped to draft and edit the manuscript; MR participated in the design and conducting the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of funding This trial was conducted as a thesis funded by the Vice-Chancellery for Research, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Conflict of Interests Authors has no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.O’Brien LM, Holbrook CR, Mervis CB, Klaus CJ, Bruner JL, Raffield TJ, et al. Sleep and neurobehavioral characteristics of 5- to 7-year-old children with parentally reported symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):554–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaditis AG, Finder J, Alexopoulos EI, Starantzis K, Tanou K, Gampeta S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in 3,680 Greek children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37(6):499–509. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery-Downs HE, O’Brien LM, Holbrook CR, Gozal D. Snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in young children: subjective and objective correlates. Sleep. 2004;27(1):87–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blunden S, Lushington K, Lorenzen B, Wong J, Balendran R, Kennedy D. Symptoms of sleep breathing disorders in children are underreported by parents at general practice visits. Sleep Breath. 2003;7(4):167–76. doi: 10.1007/s11325-003-0167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lofstrand-Tidestrom B, Hultcrantz E. The development of snoring and sleep related breathing distress from 4 to 6 years in a cohort of Swedish children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(7):1025–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spruyt K, O’Brien LM, Macmillan Coxon AP, Cluydts R, Verleye G, Ferri R. Multidimensional scaling of pediatric sleep breathing problems and bio-behavioral correlates. Sleep Med. 2006;7(3):269–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gozal D, Capdevila OS, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Metabolic alterations and systemic inflammation in obstructive sleep apnea among non-obese and obese prepubertalchildren. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2008;177(10):1142–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1670OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coughlin SR, Mawdsley L, Mugarza JA, Calverley PMA, Wilding JPH. Obstructive sleep apnoea is independently associated with an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(9):735–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters KA, Sitha S, O’brien LM, Bibby S, de Torres C, Vella S, et al. Follow-up on metabolic markers in children treated for obstructive sleep apnea. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2006;174(4):455–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-110OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tracy RE, Newman WP, 3rd, Wattigney WA, Berenson GS. Risk factors and atherosclerosis in youth autopsy findings of the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Med Sci. 1995;310(Suppl 1):S37–41. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wissler RW. An overview of the quantitative influence of several risk factors on progression of atherosclerosis in young people in the United States.Pathological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Research Group. Am J Med Sci. 1995;310(Suppl 1):S29–36. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199512000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlaud M, Urschitz MS, Urschitz-Duprat PM, Poets CF. The German study on sleep-disordered breathing in primary school children: epidemiological approach, representativeness of study sample, and preliminary screening results. Paediatr Perinat Epidem. 2004;18(6):431–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gozal D, Pope DW., Jr Snoring During Early Childhood and Academic Performance at Ages Thirteen to Fourteen Years. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1394–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamara JR, Schaefer EJ. Automated enzymatic standardized lipid analyses for plasma and lipid lipoprotein fractions. Clin Chem Acta. 1987;166(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(87)90188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-magnesium precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1982;28(6):1379–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Teacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentration in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasali E, Ip MS. Obstructive sleep apnea and metabolic syndrome: alterations in glucose metabolism and inflammation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):207–17. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-139MG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capdevila OS, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Dayyat E, Gozal D. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea: complications, management, and long-term outcomes. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):274–82. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-138MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owens JA, Mehlenbeck R, Lee J, King MM. Effect of weight, sleep duration, and comorbid sleep disorders on behavioral outcomes in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(4):313–21. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagel JF. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in primary care: evidence-based practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(4):392–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.04.060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruber A, Horwood F, Sithole J, Ali NJ, Idris I. Obstructive sleep apnoea is independently associated with the metabolic syndrome but not insulin resistance state. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coughlin SR, Mawdsley L, Mugarza JA, Wilding JPH, Calverley PMA. Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of CPAP in obese males with OSA. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(4):720–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00043306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kono M, Tatsumi K, Saibara T, Nakamura A, Tanabe N, Takiguchi Y, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is associated with some components of metabolic syndrome. Chest. 2007;131(5):1387–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blankenberg S, Barbaux S, Tiret L. Adhesion molecules and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170(2):191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangge H, Schauenstein K, Stroedter L, Griesl A, Maerz W, Borkenstein M. Low grade inflammation in juvenile obesity and type 1 diabetes associated with early signs of atherosclerosis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2004;112(7):378–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semiz S, Rota S, Ozdemir O, Ozdemir A, Kaptanoğlu B. Are C-reactive protein andhomocysteine cardiovascular risk factors in obese children and adolescents? Pediatr Int. 2008;50(4):419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford ES. C-reactive protein concentration and cardiovascular disease risk factors in children: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2000. Circulation. 2003;108(9):1053–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080913.81393.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelishadi R. Inflammation-Induced Atherosclerosis as a Target for Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases from Early Life. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2010;4:24–9. doi: 10.2174/1874192401004020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motlagh ME, Kelishadi R, Amirkhani MA, Ziaoddini H, Dashti M, Aminaee T, et al. Double burden of nutritional disorders in young Iranian children: findings of a nationwide screening survey. Public Health Nutr. 2010;14(4):605–10. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts CK, Won D, Pruthi S, Kurtovic S, Sindhu RK, Vaziri ND, et al. Effect of a short-term diet and exercise intervention on oxidative stress, inflammation, MMP-9, and monocyte chemotactic activity in men with metabolic syndrome factors. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(5):1657–65. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01292.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelishadi R, Sharifi M, Khosravi A, Adeli K. Relationship between C-reactive protein and atherosclerotic risk factors and oxidative stress markers among young persons 10-18 years old. Clin Chem. 2007;53(3):456–64. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.073668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juonala M, Viikari JS, Ronnemaa T, Taittonen L, Marniemi J, Raitakari OT. Childhood C-reactive protein in predicting CRP and carotid intima-media thickness in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(8):1883–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000228818.11968.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattsson N, Rönnemaa T, Juonala M, Viikari JS, Raitakari OT. Childhood predictors of the metabolic syndrome in adulthood.The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Ann Med. 2008;40(7):542–52. doi: 10.1080/07853890802307709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz ES, D’Ambrosio CM. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31(2):221–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lam JC, Ip MS. Obstructive sleep apnea and the metabolic syndrome. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2009;3(2):177–86. doi: 10.1586/ers.09.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Serpero LD, Sans Capdevila O, Dayyat E. Obstructive sleep apnea and endothelial function in school-aged nonobese children: effect of adenotonsillectomy. Circulation. 2007;116(20):2307–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam JC, Ip MS. An update on obstructive sleep apnea and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13(6):484–9. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3282efae9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]