Abstract

Shifts in social structure and cultural practices can potentially promote unusual combinations of allele frequencies that drive the evolution of genetic and phenotypic novelties during human evolution. These cultural practices act in combination with geographical and linguistic barriers and can promote faster evolutionary changes shaped by gene–culture interactions. However, specific cases indicative of this interaction are scarce. Here we show that quantitative genetic parameters obtained from cephalometric data taken on 1,203 individuals analyzed in combination with genetic, climatic, social, and life-history data belonging to six South Amerindian populations are compatible with a scenario of rapid genetic and phenotypic evolution, probably mediated by cultural shifts. We found that the Xavánte experienced a remarkable pace of evolution: the rate of morphological change is far greater than expected for its time of split from their sister group, the Kayapó, which occurred around 1,500 y ago. We also suggest that this rapid differentiation was possible because of strong social-organization differences. Our results demonstrate how human groups deriving from a recent common ancestor can experience variable paces of phenotypic divergence, probably as a response to different cultural or social determinants. We suggest that assembling composite databases involving cultural and biological data will be of key importance to unravel cases of evolution modulated by the cultural environment.

Keywords: cultural evolution, morphology, mtDNA, multiple factor analysis, Amerindians

Classic hypotheses about modern human evolution frequently assume that the evolutionary forces acting on the populations are triggered mainly by changes in the external (climatic, geographic, topological) environment. However, recent anthropological studies suggest that shifts in cultural practices can potentially modify environmental and behavioral conditions, thus promoting faster evolutionary rates shaped by gene–culture interactions (1–5). Because humans have lived in small aggregates in most of their evolutionary history, studying the influence of cultural practices on the demographic and genetic parameters of small groups can shed more light on modeling the effect of culture on biological evolution. These cultural practices act in combination with geographical and linguistic barriers and can promote faster evolutionary changes shaped by gene-culture interactions. In this context, Neel and Salzano (6), based on observations among South American native populations, postulated that bands of endogamous hunter-gatherers may split under social tensions, such as dictates of war, disease, and other autochthonous conditions. These fissions generally occur along kinship lines, leading to a highly nonrandom migration. Therefore, social structure and cultural practices promote demographic isolation and periodic reshuffling of genetic variation, creating unusual combinations of allele frequencies that may play a role in promoting fast evolution (1–5). However, well-documented examples regarding cultural shifts and evolutionary rates involving Native Americans and suggesting some degree of impact of the former on the genetic, phenotypic, or life-history trait variability, are inexistent or very scarce (7). Given the decades of efforts dedicated to collect both cultural, as well as biological data (8, 9), the Jê-speaking groups from the Brazilian Central Plateau provide a good framework to compare patterns of social structure, cultural practices, and subsistence strategies versus patterns of biological (genetic and phenotypic) variability.

Here we compare patterns of genetic, phenotypic, geographic, and climatic variation, as well as the amount and pace of phenotypic change across a tree depicting the inferred splits among six populations from the Brazilian Amazon and Central Plateau. To further evaluate the association among the observed phenotypic evolution with several environmental, biological, and cultural factors, we calculated a multiple factor analysis (MFA) (10) using a set of morphological, climatic, social, and life-history traits from original data recorded on the seventies by one of us (F.M.S.) and colleagues with the logistic support of the Brazilian National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) (11–13). First, eight cephalometric measurements were explored using principal component analysis (PCA) and matrix correlation methods were used to contrast genetic (noncoding mtDNA sequences, the only genetic data available for the six populations), phenotypic, geographical, and climatic distances among groups (Fig. 1, and Datasets S1 and S2). Second, we used the mtDNA and main quantitative genetics results to reconstruct a population tree. For this analysis an additional population was included as an outgroup (the Otomí of Mexico), to provide a geographically distant source of reference (Fig. 2).

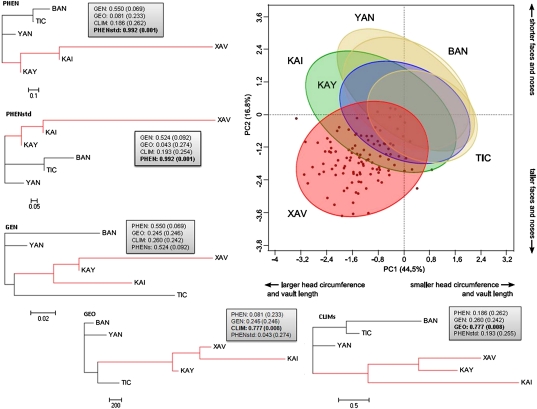

Fig. 1.

First two principal components depicting variation on the sex-standardized cephalometric variables. Ellipses represent the 75% of variation for each group. Red, Xavánte; green, Kaingang; blue, Kayapó; light brown, non-Jê groups, Yanomami, Ticuna, and Baniwa. Neighbor-Joining trees for each of the five distance matrices are also displayed. The Jê-speaking clade is represented in red. Gray boxes provide Mantel correlation scores and associated P values between each matrix and the remaining four ones (CLIM, Climatic; GEN, genetic; GEO, Geographic; PHEN, phenotypic; PHENstd, phenotypic standardized). Statistically significant values are shown in bold. The trees were rooted using the Yanomami.

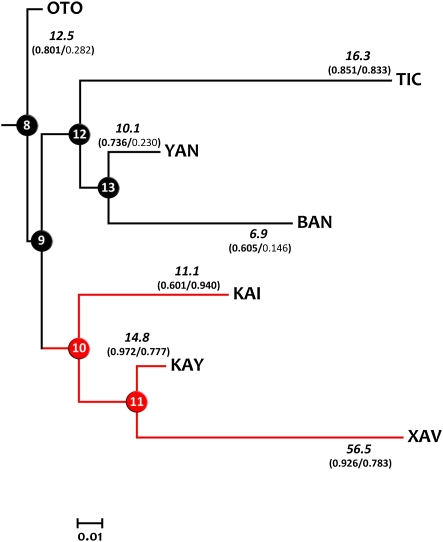

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-Joining tree obtained after HVS-1 mtDNA FST distances and main quantitative genetics results. Red lines indicate the Jê-speaking clade. Numbers in italics on each branch indicate morphological pace of change (mP). Numbers within parentheses correspond to vector correlation values among evolutionary path (Δz) and phenotypic (pmax)/genetic (gmax) LLERs, respectively (Table S2). Significant correlations are shown in bold. Numbers in nodes represent arbitrary labeling used to present results. OTO refers to the Mexican Otomí, included here as outside reference.

Linguistic data suggest that the genetically sister-groups Xavánte and Kayapó (central and northern Jê-speakers, respectively) can be seen also as linguistic sister groups that diverged some 1,500–2,000 y before present (14). Main cultural differences among Xavánte and Kayapó involve marriage practices, clan and political organization, endogamy and exogamy patterns, and other social traits (Dataset S1). The topology and branch lengths of the genetic tree (Fig. 2) were used as the basis to compute a series of quantitative genetics parameters aimed to test if abrupt changes on cultural practices, like those existing among the Xavánte and Kayapó, are congruent with disruptions in parameters depicting the direction, amount, and pace of evolution. Maximum-likelihood estimates of the ancestral states (15) in each node of the tree for each variable were used to compare measures of morphological amount (mA) and pace (mP) of change. The direction of evolution (Δz) across each branch, as well as the phenotypic and genetic lines of least resistance to evolutionary change (LLER) (pmax and gmax, respectively) (16) for each tip and node of the tree were also obtained following published formulae (17) (Tables S1 and S2). Because the genetic LLER was unavailable for the samples studied here, we used data from the Austrian population of Hallstatt (18) as a proxy to gmax.

Finally, we used MFA (10) to analyze simultaneously the relationship among the phenotypic, climatic, social, and life-history traits compiled in Dataset S1. MFA solves the problem of analyzing several sets of variables measured in different scales simultaneously, balancing the influences of these sets.

Results and Discussion

The exploratory statistical morphological analysis is summarized in the first two principal components (PCs) (Fig. 1) of the sex-corrected cephalometric measurements. The PC analysis shows that Xavánte is the most differentiated group, characterized by larger head circumferences, longer and narrower vaults, taller and narrower faces, and broader noses. Phenotypic and genetic distances were correlated, with r = 0.55 (P = 0.069). This P value should be regarded as borderline significant because the distance matrix comparison is only based on six samples, which is a small number for this type of test. However, neither the phenotypic nor the genetic distances were correlated to matrices depicting geographic or climatic distinctions among samples (Fig. 1). In other words, the divergent nature of the Xavánte observed on Fig. 1 is independent of the geographic separation of the samples and the climate where they lived.

The Neighbor-Joining tree estimated from mtDNA FST distances combined with main results concerning quantitative genetics parameters are presented in Fig. 2 and Tables S3–S6. The group-specific (Table S3), as well as the node-specific principal axes of morphological variation were correlated among them and with gmax, representing equal LLERs (Tables S4 and S5). In addition, evolutionary changes (Δz) were significantly aligned to the phenotypic and genetic LLERs (Table S6) for most of the comparisons, including the entire Jê group. The most remarkable result of our study is the Xavánte pace of morphological change; the mP on branch 11-XAV (56.5) is 3.8-times greater in relation to the average pace (14.89), which included the geographically and linguistically distant Otomí. The Xavánte pace is also distinct in relation to the morphological change of their sister group (mP 11-KAY = 14.8). This result suggests that the degree of phenotypic diversification of the Xavánte from the common ancestor with its genetic and linguistic sister group, the Kayapó, was accelerated by some mechanism in comparison with the pattern observed in the remaining branches of the tree. Note that because the effective population size of mtDNA is one-quarter of that for nuclear autosomal loci, and that Xavánte marriage practices (sororal polygyny) tend to, by intensifying genetic drift, inflate the mitochondrial divergence (branch length) over the overall genetic divergence, then the morphological pace (the ratio between morphological amount of change and branch length) is somehow underestimated.

Quantitative genetic theory predicts that the direction of morphological divergence of closely related groups will be biased toward the genetic LLER, the leading eigenvector of the matrix of genetic variance-covariance matrix (16, 19). Our results support this notion, because the vectors of morphological diversification were ubiquitously aligned with both the phenotypic and genetic LLERs. Previous analyses on the stability of the P-matrices on modern humans reinforce this idea (20), as well as the notion that within-population covariation patterns are stable across different populations because of the interplay among both, developmental and functional constraints and selection (16). However, the direction of divergence between two groups may correlate with the genetic LLER for a variety of reasons (16). In the present case, the most evident alternative would be that gene flow between populations might increase genetic variance within groups along the lines of divergence between populations (19). If genotypes are introduced into a population from another population, then the presence of these new genotypes will skew the distribution of genetic effects toward the axis of divergence between populations. However, previous studies in lowland South Amerindian populations suggest that gene flow was a restricted force in comparison with genetic drift (21). Furthermore, ethnographic studies reveal a strong cultural and reproductive isolation between Xavánte and Kayapó, which probably triggered the genetic drift experienced by the Xavánte, despite its linguistic affinity and recent divergence (12, 14). In addition, admixture with non-Europeans is very unlikely because of the recent dates of such contact (Dataset S1). Note, however, that the fast evolution (mP) observed in the diversification of the Xavánte is independent of the mechanism invoked to explain the alignment among divergence and LLERs, because it only depends on the comparison among morphological and genetic divergences across the branches of the tree.

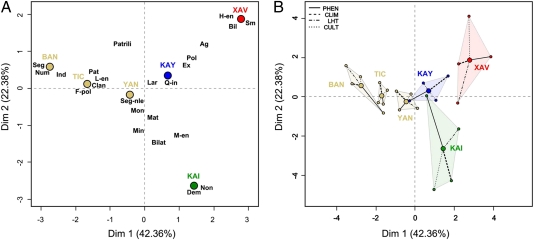

MFA global analysis, which balanced the influence of phenotypic, climatic, social, and life-history trait datasets, is presented in Fig. 3A, which shows the distribution of individuals (population means) for the global analysis. This analysis indicated that the first dimension separates Jê-speaking groups from non–Jê-speakers, where as Jê groups are separated across the second dimension (Fig. 3 and SI Results and Fig. S1). Specifically, the Xavánte were evaluated as presenting longer and narrower vaults, along with wider noses and faces. The Baniwa, occupying the opposite extreme of the first dimension, can be then characterized by the contrary pattern of skull shape. The second axis is essentially explained by differentiation separating two Jê-speaking groups (Xavánte and Kaingang).

Fig. 3.

MFA results. (A) Plot of populations and sociocultural categories as listed in Dataset S1. (B) “Partial individuals' superimposed representation” representing each population viewed by each group of variables and its barycentre. Red, Xavánte; green, Kaingang; blue, Kayapó; light brown, non Jê groups, Yanomami, Ticuna, and Baniwa. The mean population points in A are here joined to their corresponding partial points, depicting the influence of each set of variables.

Many sociocultural categories, noticeably these involving marriage-type, are close to the origin of the principal component map, which means that these categories are not related to skull shape or climate, and in consequence to the Xavánte-Baniwa or Xavánte-Kaingang separation. However, the categories “Bilocal” (Bil) marital residence, “High endogamy” (H-en), and “Small extended” (Sm) domestic organization are characteristic of the Xavánte, with high coordinates on the first and second axes. Moreover, “Patrilineal” (Patrili) descent, “Patrilocal” (Pat) residence, “Low endogamy” (L-en), “Clan communities” (Clan), and “Frequent polygyny” (Fpol) are characteristic of Baniwa at the opposite end of the first axis (Fig. 3A). Alternatively, Xavánte and Kaingang are in opposed positions along the second dimension, the Kaingang being characterized by “Non-sororal cowives in same dwelling” (Non) and “Demes, not segmented” (Dem) for community marriage organization. Conversely, Kayapó is characteristic from the climatic point of view, but this does not induce a particular phenotypic divergence. In terms of sociocultural variables they are distinct for “Sororal polygyny” (Pol), “Extended families” (Ex), and “Quasi-lineages” (Q-in) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3B shows the “partial individuals’ superimposed representation” and depicts each population as viewed from each group of variables and its barycenter. Interpretation is analogous to a generalized procrustes analysis, where the homologous points (the variables referring to the same population) are shown as close one to the other as possible. This interpretation suggests that the Xavánte are highly characteristic from a phenotypic and cultural point of view, differentiating this population along the first and second axis, respectively, but not from a climatic point of view (note that the climate axis drags the Xavánte barycenter to the origin of coordinates). Conversely, its sister group, the Kayapó, is characteristic from the climatic point of view but does not display a particular phenotypic differentiation.

Departing from the classic view that human evolution is the sole result of adaptation to the external environment, the rapid pace of evolution exhibited by the Xavánte could be interpreted as a pattern more likely tied to cultural rather than to noncultural environmental differences, promoting isolation and leading to a rapid phenotypic differentiation. Sexual selection could be the culture-generated force that would explain our results and cause such divergence. For example, the reproductive success of some of the Xavánte chiefs is well documented on the ethnographic missions of the 1970s. When familiar data were collected on the São Domingo village, 25% of the inhabitants were sons of the Xavánte chief Apoena, who had five wives and a vast array of alliances (12). Thus, sexual selection favoring wealthy and well-positioned men in socioeconomic terms, rather than men carrying desirable phenotypic attributes, could have been a solid mechanism driving rapid micro evolution in the Xavánte society and other similar groups.

Conclusions

The interpretation of the biological evidence regarding modern human origins depends, among other things, on assessments of the structure and the variation of ancient populations (22). Because we lack observational data from the cultural patterns operating when the first anatomically modern humans appeared, between 200,000 and 120,000 y ago, we can instead exploit the cultural and biological data collected on contemporary groups to test if strong shifts on sociocultural patterns are paralleled with some marker of rapid divergence. Our results support previous assertions that genes and culture plausibly coevolve, often revealing patterns and rates of change that are uncharacteristic of more traditional population genetic theory. Gene–culture dynamics are typically faster, stronger and operate over a broader range of conditions than conventional evolutionary dynamics, suggesting that gene-culture coevolution could be the dominant mode of human evolution (1–5, 23). Previous empirical studies (5) demonstrated that culture-specific traits are important to understand biological parameters like fitness. Our findings expand this notion to the detail that some phenotypes can also evolve rapidly as a response to culture-mediated processes. The potential coevolution among genes, phenotypes and culture, especially after the onset of the Neolithic, deserves more attention in the modern human evolution discussions.

Materials and Methods

Samples.

Table S7 shows the sample composition, sample sizes, linguistic affiliation, and geographic location of the populations considered. Previous research and fieldwork details can be found in refs. 6, 8, 9, 11, and 12.

PCA, Matrix Correlation, and Population Trees.

Eight cephalometric variables (HC, head circumference; NGH, facial height; NLH, nasal height; NLB, nasal breadth; GOL, glabello-occipital length; XCB, cranial breadth; ZYB, zygomatic breadth; GOB, bigonial diameter) were recorded using conventional anthropometric tools on 1,203 individuals from the six populations listed in Table S7. Sex-standardized form and shape (size-corrected) data were used to compute PCA and squared Mahalanobis distances, following ref. 24. The Darroch Mosimann (25) method was used to remove size effects, whereas sex-differences were corrected by adding the difference between male and female means to each female. The matrices of sex-standardized form, and sex-standardized size-corrected shape distances were labeled PHEN and PHENstd, respectively. Phenotypic Mahalanobis distances were obtained using an average heritability value (h2 = 0.37) for the eight traits, derived from Martínez-Abadías et al. (18). Therefore, these distances can be considered as a proxy to genetic distances (24).

Additionally, genetic, geographic, and climatic 6 × 6 distance matrices were obtained. A sample of 435 hypervariable segment (HVS)-1 mtDNA sequences (Dataset S2) were used to obtain the “GEN” matrix of mtDNA FST distances. The among-group geographic distances matrix (GEO) was calculated using Haversine great-circle distances in kilometers (26). Climatic variables were obtained from http://www.worldclim.org, which offers a set of global climate layers (climate grids) (27) with a spatial resolution of a square kilometer. Then, the matrix of climatic distances (CLIM) was formed by Euclidean distances using six variables (listed in Dataset S1) calculated after standardizing them to mean zero and SD one.

The five resulting matrices, PHEN, PHENstd, GEN, GEO, and CLIM, were then compared for proportionality using Mantel tests (28), and Neighbor-Joining trees (29) were obtained to visualize similarities and differences among patterns of variation (Fig. 1).

Quantitative Genetics Parameters.

The topology and branch lengths of the mtDNA tree were used to compute a series of quantitative genetics parameters. First, maximum-likelihood estimates of quantitative ancestral states were used to compare measures of morphological amount (mA) and pace (mP) of change (definitions in Tables S1 and S2) using the cephalometric data together with the genetic tree (15) as implemented in the ANCML program. All quantitative genetic parameters were obtained and handled as suggested in ref. 17. The direction of evolution (Δz) within each branch was estimated as the difference vector in the eight averages of each population pair. The amount and pattern of variation and covariation within a group was estimated as the pooled within-group variance/covariance matrix (W). Its first principal component is the linear combination of measurements accounting for the largest portion of phenotypic variance within a group, and can be considered as the phenotypic line of least resistance to evolutionary change (16). Additionally, we have also used a pmaxAmerindian computed on the eight variables derived from 3D coordinates recorded on a sample of 408 skulls from 11 North and South American populations. Although the genetic line of least evolutionary resistance (gmax), computed as the first principal component of the G matrix of additive genetic variances and covariances among the eight cephalometric traits is unavailable for the samples studied here, we have used an estimate based on the pedigreed-structured skull collection from Hallstat (Austria) studied by Martínez-Abadías et al. (18). This collection furnishes a unique chance to compute quantitative genetic parameters for skull shape because skulls were individually identified and church records could be used to reconstruct genealogical relationships (18, 30), providing a crucial advantage over previous studies of human evolution that have used phenotypic covariance as a proxy for genetic data.

Finally, with both Δz and pmax (or pmaxAmerindian and gmax) estimated, we obtained the angle (ø) formed between them as a measure of how closely morphological diversification follows the LLER. When evolutionary change occurs primarily along the LLER, ø will approach zero and, conversely, as Δz deviates from gmax, ø will increase. We used the cosine of ø (vector correlation) to measure the relationship between Δz and gmax or pmax; the smaller the angle the larger the correlation between vectors (see Table S1 for definitions). Vector correlation was used as a measure of the similarity of any two vectors, as used in ref. 17. The brokenstick model was used to obtain 1,000 random eight-element vectors from a uniform distribution and then correlate each random vector to a fixed isometric vector (all elements equal to 0.3). Our sample showed an average correlation of 0.326 and a SD of 0.188, both values being the same no matter which fixed vector was used for comparisons with the random vectors. These two statistics allowed us to test whether the correlation of any two observed vectors is significantly different from the correlation between two vectors expected by chance.

Multiple Factor Analysis.

The MFA method (10) is useful to analyze datasets where variables are structured into groups. The analysis is carried out in two steps. First, a PCA is performed on each dataset, which is then “normalized” (to make these groups of variables comparable) by dividing all its elements by the square root of the first eigenvalue obtained from its PCA. Second, the normalized datasets are merged to form a unique matrix and a global PCA is performed on this matrix. The individual datasets are then projected onto the global analysis to analyze communalities and discrepancies.

MFA was used to simultaneously study the relationship among phenotypic, climatic, sociocultural, and life-history traits (listed in Dataset S1). We performed the analysis using R 2.7.0 (31) and the FactoMineR package for the R-system, available from the Comprehensive R Archive Network at http://CRAN.Rproject.org/. See Tables S8 and S9 for eigenvalues and percentage of variance explained by the axes from separate PCA and from MFA (global) analysis and correlations between variables and each global factor of MFA analysis, respectively.

Ethical Approval.

Ethical approval for the present study was provided by the Brazilian National Ethics Commission (CONEP Resolution no. 123/98). Informed oral consent was obtained from all participants, because they were illiterate, and they were obtained according to the Helsinki Declaration. The Brazilian National Ethics Commission approved the oral consent procedure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Fabricio R. Santos, Kenneth M. Weiss, J. Saravia, Sidia M. Callegari-Jacques, C. Paschetta, M. González, L. Castillo, and M. Becué for help in different aspects of this work.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1118967109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Durham W. Coevolution: Genes, Culture, and Human Diversity. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laland KN, Odling-Smee J, Myles S. How culture shaped the human genome: Bringing genetics and the human sciences together. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:137–148. doi: 10.1038/nrg2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richerson PJ, Boyd R, Henrich J. Colloquium paper: Gene-culture coevolution in the age of genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(Suppl 2):8985–8992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914631107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laland KN. Exploring gene-culture interactions: Insights from handedness, sexual selection and niche-construction case studies. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3577–3589. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richerson PJ, Boyd R. Not By Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neel JV, Salzano FM. Further studies on the Xavante Indians. X. Some hypotheses-generalizations resulting from these studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1967;19:554–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckerman S, et al. Life histories, blood revenge, and reproductive success among the Waorani of Ecuador. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8134–8139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901431106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salzano FM, Neel JV, Gershowitz H, Migliazza EC. Intra and intertribal genetic variation within a linguistic group: The Ge-speaking indians of Brazil. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1977;47:337–347. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330470214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salzano FM. Multidisciplinary studies in tribal societies and human evolution. In: Meier RJ, Otten CM, Abdel-Hameed F, editors. Evolutionary Models and Studies in Human Diversity. The Hague: Mouton; 1978. pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escofier B, Pagès J. Multiple factor analysis (AFMULT package) Comput Stat Data Anal. 1994;18:121–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salzano FM, Callegari-Jacques SM. South American Indians. A Case Study in Evolution. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coimbra CEA, Flowers NM, Salzano FM, Santos RV. The Xavante in Transition. Health, Ecology, and Bioanthropology in Central Brazil. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salzano FM, Bortolini MC. The Evolution and Genetics of Latin American Populations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urban G. The history of Brazilian culture according to native languages. In: Carneiro-da-Cunha M, editor. History of the Brazilian Indians. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras; 1998. pp. 87–102. (Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schluter D, Price T, Mooers AØ, Ludwig D. Likelihood of ancestor states in adaptive radiation. Evolution. 1997;51:1699–1711. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb05095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schluter D. Adaptive radiation along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution. 1996;50:1766–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marroig G, Cheverud JM. Size as a line of least evolutionary resistance: Diet and adaptive morphological radiation in New World monkeys. Evolution. 2005;59:1128–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-Abadías N, et al. Heritability of human cranial dimensions: Comparing the evolvability of different cranial regions. J Anat. 2009;214:19–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillaume F, Whitlock MC. Effects of migration on the genetic covariance matrix. Evolution. 2007;61:2398–2409. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.González-José R, Van Der Molen S, González-Pérez E, Hernández M. Patterns of phenotypic covariation and correlation in modern humans as viewed from morphological integration. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2004;123:69–77. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarazona-Santos E, et al. Genetic differentiation in South Amerindians is related to environmental and cultural diversity: Evidence from the Y chromosome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1485–1496. doi: 10.1086/320601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackermann RR. Patterns of covariation in the hominoid craniofacial skeleton: Implications for paleoanthropological models. J Hum Evol. 2002;43:167–187. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2002.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehrlich PR. Human Natures: Genes, Cultures, and the Human Prospect. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Relethford JH, Crawford MH, Blangero J. Genetic drift and gene flow in post-famine Ireland. Hum Biol. 1997;69:443–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darroch JN, Mosimann JE. Canonical and principal component of shape. Biometrika. 1985;72:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinhasi R, von Cramon-Taubadel N. Craniometric data supports demic diffusion model for the spread of agriculture into Europe. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hijmans R, Cameron SE, Parra JR, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 1967;27:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sjøvold T. A report on the heritability of some cranial measurements and non-metric traits. In: Van Vark GN, Howells WW, editors. Multivariate Statistical Methods in Physical Anthropology. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company; 1984. pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Team RDC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.