Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) are seven transmembrane helix proteins that couple binding of extracellular ligands to conformational changes and activation of intracellular G proteins, GPCR kinases, and arrestins. Constitutively active mutants are ubiquitously found among GPCRs and increase the inherent basal activity of the receptor, which often correlates with a pathological outcome. Here, we have used the M257Y6.40 constitutively active mutant of the photoreceptor rhodopsin in combination with the specific binding of a C-terminal fragment from the G protein alpha subunit (GαCT) to trap a light activated state for crystallization. The structure of the M257Y/GαCT complex contains the agonist all-trans-retinal covalently bound to the native binding pocket and resembles the G protein binding metarhodopsin-II conformation obtained by the natural activation mechanism; i.e., illumination of the prebound chromophore 11-cis-retinal. The structure further suggests a molecular basis for the constitutive activity of 6.40 substitutions and the strong effect of the introduced tyrosine based on specific interactions with Y2235.58 in helix 5, Y3067.53 of the NPxxY motif and R1353.50 of the E(D)RY motif, highly conserved residues of the G protein binding site.

Keywords: constitutive activity, GPCRs, light-activated, rhodopsin

The more than 800 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in a typical eukaryotic genome allow signaling between cells and tissues and provide an important link to our environment as the principal receptors for our senses of taste, smell, and vision. Rhodopsin, the dim-light sensor in rod photoreceptor cells, is the prototypical receptor to study the molecular mechanisms of GPCR activation. This is due mainly to a wealth of biophysical and spectroscopic methods that take advantage of the covalently bound chromophore retinal. The possibility to purify rhodopsin directly from its native membrane furthermore facilitated its crystallization and structure determination. Comparison of structures with spectroscopic and biochemical data allowed the accurate attribution to specific states and to track the sequence of events during activation (1). This unique framework includes structures of the ground state from native (2, 3) and thermo-stabilized recombinant protein (4), several metastable intermediates (5, 6) with bound all-trans-retinal and an activated form of the apoprotein opsin (7). Opsin has also been solved in complex with a peptide resembling the C-terminus of the G protein alpha subunit (GαCT), which provided the first molecular insights into how the G protein binds the active receptor (8). Recently, active state structures that contain the retinal agonist have been solved using two different approaches. In one, the mutation E113Q3.28 (9) was incorporated into rhodopsin to neutralize the counterion of the retinal Schiff base (10) preventing dissociation of retinal. In the other, opsin crystals were grown and then back-soaked with all-trans-retinal (11). Both structures share many features that are expected for the fully active metarhodopsin-II conformation, although they differ in the precise binding mode of retinal. The E113Q3.28 mutant lacks the Schiff base covalent bond between retinal and the protein and the back-soaked opsin shows an unexpected rotation of the ligand.

In native membranes, rhodopsin is activated by light-induced isomerization of the covalently bound inverse agonist 11-cis-retinal to the full agonist all-trans-retinal within a very tight binding pocket. Subsequent hydrolysis of the covalent bond between retinal and the protein leads to release of the agonist and relaxation to the, under physiological conditions, inactive opsin state. In contrast to other GPCRs, incubation of opsin with its full agonist all-trans-retinal leads only to very low levels of activity. This makes physiological sense as rhodopsin has been evolved as light sensor and not to detect all-trans-retinal. It, however, opens the question to what extent opsin crystals bind all-trans-retinal in the same conformation as in metarhodopsin-II, where all-trans-retinal is formed by light-induced isomerization of 11-cis-retinal.

In an attempt to determine a structure of light activated rhodopsin that is as close to the fully active metarhodopsin-II as possible, we work with constitutively active rhodopsin mutants. Constitutively active mutants have been described for many GPCRs (12). They increase the basal activity of the receptor and many have been linked to human diseases. For example, constitutive activity of rhodopsin leads to congenital stationary night blindness (13) and retinitis pigmentosa (14). Constitutively active mutants of rhodopsin can be categorized into two classes: those that target the retinal binding pocket and those that target the ionic lock region and G protein binding site. With the crystal structure of the constitutively active E113Q3.28 counterion mutant (9), we have recently presented an example for the first category. Here we present an example for the second category, the constitutively active M257Y6.40 rhodopsin mutant. The crystal structure of the light-activated mutant in complex with the GαCT peptide explains how modification of position 2576.40, close to the G protein binding site, leads to constitutive activity and why tyrosine specifically has the strongest effect. Most importantly, the M257Y6.40 mutation does not change the retinal binding site and shows all-trans-retinal covalently bound in its native environment. A comparison with published biochemical, spectroscopic, and structural data shows that the M257Y/GαCT structure presents all the features of metarhodopsin-II, the G protein binding conformation obtained by the natural activation mechanism.

Results

Biochemical and Spectroscopic Analysis.

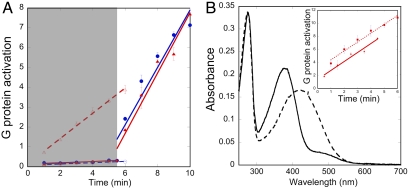

The constitutively active mutation M257Y6.40 was introduced in the context of another rhodopsin mutant, N2C/D282C, containing an engineered disulfide bond known to enhance thermal stability of the protein (SI Appendix, Fig. 1) without affecting activity (15, 16). We previously solved the structure of this stabilized mutant and showed it to be virtually identical to the native protein (4). To investigate the biochemistry of the M257Y6.40 mutation in the context of the N2C/D282C background, we first analyzed its ability to activate the G protein transducin (Fig. 1). G protein activation is fully suppressed by reconstitution with the inverse agonist 11-cis-retinal, in both thermo-stabilized N2C/D282C and N2C/M257Y/D282C (from hereon called M257Y6.40). G protein activation of M257Y6.40 and N2C/D282C rhodopsin is virtually indistinguishable if triggered by light-induced isomerization of retinal (Fig. 1A). By contrast, clear differences in activity can be observed in the absence of retinal, where N2C/D282C opsin is completely inactive, but inclusion of the M257Y6.40 mutation increases the basal activity to about 40% of the photoactivated state. Reconstitution of the M257Y6.40 opsin with all-trans-retinal further increases the activity to the same level as after light activation of rhodopsin reconstituted with 11-cis-retinal (Fig. 1B, Inset).

Fig. 1.

Biochemical assessment of M257Y6.40 in the context of the N2C/D282C background. (A) Assessment of G protein activation (pmol) by bovine opsin (open symbols and dashed regression lines) or 11-cis-retinal reconstituted rhodopsin (solid symbols and regression lines) for the N2C/D282C (blue circles) and N2C/M257Y/D282C (red triangles) mutants. The shaded area represents dim red light conditions that preserve the inactive ground state of rhodopsin. At time 5 min 30 s, samples were subjected to bright illumination and the rest of the data were collected. (B) Ability of opsin to covalently bind all-trans-retinal. Absorbance spectra of purified N2C/M257Y/D282C reconstituted with all-trans-retinal were recorded at pH 7.4 (solid line) and pH 3.5 (dotted line). At pH 7.4, the pigment absorbs maximally at 380 nm, which is characteristic of metarhodopsin-II and free retinal. Acidification causes a red-shift to 415 nm, resulting from the protonation of the Schiff base formed between opsin and retinal. The inset shows that reconstitution of N2C/M257Y/D282C with all-trans-retinal (squares, dotted regression line, slope = 1.37 pmol/ min) increases G protein activation levels to those of fully light activated metarhodopsin-II that had been reconstituted with 11-cis-retinal (red triangles, solid regression line, slope = 1.35 pmol/ min). Error bars in (A) and (B) represent standard error, n = 3.

Spectral analysis of the M257Y6.40 pigment reconstituted with all-trans-retinal under dim red light shows a maximum absorbance at 380 nm that red-shifts to 415 nm upon protonation of the Schiff base through acidification (Fig. 1B). Side-by-side analysis of the ability of N2C/D282C opsin to reconstitute with all-trans-retinal produced only a minor peak at 380 nm that did not significantly shift upon acidification. These results are consistent with previous reports that all-trans-retinal does not reconstitute and activate wild-type opsin well but only binds covalently in correlation with increasing constitutive activity in mutants (17).

Even though M257Y6.40 opsin expresses full activity when incubated with all-trans-retinal, we first reconstituted it with 11-cis-retinal under dim red light during purification. Just before crystallization, we activated the reconstituted ground state by selective isomerization of the protonated Schiff base linked 11-cis-retinal with a > 515 nm long-pass filter to prevent further isomerization within the activated protein. To increase the stability of the active conformation, we incubated the receptor with the GαCT peptide, which specifically binds metarhodopsin-II (18). The peptide includes the K341L mutation that increases its binding affinity (19). Fourier transform infrared difference spectroscopy (FTIR) confirmed that these conditions lead to formation of metarhodopsin-II under crystallization conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. 2). Crystals of this light activated receptor grew readily under previously reported conditions (9) and exhibited the faint yellow color that is characteristic for retinal.

Structure of the M257Y/GαCT Complex.

The crystal structure of M257Y/GαCT was solved at 3.3 Å resolution using the E113Q/GαCT rhodopsin structure (9) as a molecular replacement model. As a test against model bias we excluded the GαCT peptide and all heteroatoms, including retinal, from the initial search model. A single M257Y/GαCT complex was found per asymmetric unit and was refined to a crystallographic R value of 0.22 and an Rfree of 0.26 (SI Appendix, Table 1). Our final structural model contains residues 1-326 of rhodopsin with mutations N2C/D282C/M257Y and all eleven residues of the GαCT peptide including the K341L mutation.

In comparison to the nonrhodopsin GPCR structures solved so far we could crystallize the receptor using very few alterations of the protein. In addition, expression in mammalian cells allowed us to include most of the posttranslational modifications described for the wild-type protein isolated from retinas, with the exception of glycosylation at position 2, which has been mutated to a cysteine to introduce the stabilizing disulfide bond (16) and a partially disordered palmitoylation of C322. The N-glycan at position 15 is based on the homogenous glycosylation pattern of the HEK293-GnTI- cell line (20) used for expression and has been built as GlcNAc2-Man1 with the remaining four mannose sugars being disordered. Several contacts between the N-glycan and the palmitoyl chains that fill the cavity between the two rhodopsin molecules in the crystallographic dimer suggest that posttranslational modifications were an important factor in crystal formation. Beside the posttranslationally modified polypeptide, the structure contains one octyl-glycoside molecule, one acetate molecule bound close to a proposed exit channel for retinal (21), density for nine of the 18 water molecules identified previously in the structure of constitutively active E113Q3.28 rhodopsin (9), and the covalently bound all-trans-retinal agonist. The structures of constitutively active E113Q3.28 and M257Y6.40 rhodopsin are very similar with an average RMSD(Cα) of 0.316 Å. Specific differences, however, can be observed close to where the mutations have been introduced; i.e., in the retinal binding site for the E113Q3.28 mutant and the G protein binding sites for the M257Y6.40 mutant.

Ionic Lock Region and G Protein Binding Site.

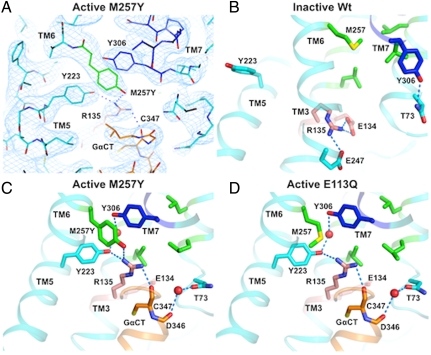

In order to obtain a crystal structure of light activated metarhodopsin-II, we have used one of the strongest constitutively active single mutations in rhodopsin (17). The M257Y6.40 mutant increases constitutive activity by altering the ionic lock region close to the G protein binding site (Fig. 2). This region contains the E(D)RY motif in transmembrane helix 3 (TM3) and is close to the NPxxY motif in TM7, both of which are highly conserved in Class A GPCRs and have been shown to be involved in activation by mutagenesis (22) and FTIR studies (23) and, more recently, solid state NMR (24).

Fig. 2.

Effect of the M257Y6.40 mutation on the ionic lock region. The 2Fo-Fc density map (A, blue mesh, contoured at 1.5σ) indicates a high degree of order around the NPxxY (dark blue) and E(D)RY motifs (salmon) that are close to the binding site for the G protein peptide GαCT (orange). The bulky side chains of Y2235.58 and Y3067.53, as well as the mutated side chain of Y2576.40 can be accurately positioned within their respective densities. In the ground state of wild-type rhodopsin (B), M2576.40 is part of the hydrophobic barrier (green) that separates the NPxxY motif from the ionic lock region including the E(D)RY motif. The M257Y6.40 mutation (C) interferes with this packing and lowers the energy barrier for reorganizations of TM6 that characterize the active conformation. In the structure of the constitutively active E113Q3.28 structure (D) the hydrophobic barrier has opened and Y2235.58 in TM5 and Y3067.53 of the NPxxY motif in TM7 swing into the created cavity, stabilized by a water-mediated H-bond network (9). In both active state structures (C + D), the ionic lock interactions between R1353.50 and E1343.49 of the E(D)RY motif in TM3 and E2476.30 in TM6 are opened allowing R1353.50 to adopt an elongated rotamer that forms part of the GαCT peptide binding site. The constitutively active M257Y6.40 mutant (C) introduces only minor changes to the overall structure of the ionic lock region, however the introduced tyrosine forms an edge-face interaction with Y2235.58, a parallel-displaced π-π stacking interaction to Y3067.53, and hydrophilic interactions to R1353.50, three interactions that stabilize the open G protein binding site.

The M257Y6.40 mutation modifies the hydrophobic barrier between the NPxxY motif and the G protein binding site by introducing a hydrophilic hydroxyl group that disturbs the tight helix packing in the ground state. The M257Y/GαCT active state shows the tilted rotation of TM6 that opens the G protein binding site and a reorganization of H-bond networks (9). The Cα of position 257 is correspondingly shifted by 3.1 Å with respect to the ground state [1GZM(3)]. The rearrangements during activation bring the introduced tyrosine in a position that is parallel to residue Y3067.53 of the NPxxY motif. The distance between the centers of both phenolic rings is 4.4 Å, which is compatible with a parallel displaced π-π stacking interaction. In addition, one side of the Y2566.40 phenolic ring forms an edge-face interaction with the phenolic ring of Y2235.58. While these interactions stabilize the position of the involved phenolic rings, the hydroxyl group of Y2576.40 forms a hydrogen bond with the amine group of R1353.50 from the E(D)RY motif.

Only minimal modifications are necessary to form these interactions, with the Cα atom of Y2576.40 differing by only 0.3 Å from the E113Q3.28 active state structure, which contains the native methionine at this position. The Y2576.40 side chain maintains a favorable rotamer that positions the hydroxyl group at just the right distance to interact with R1353.50 without chemical strain and without the need of R1353.50 to reposition and compromise its interaction with the C-terminus of the G protein. Several amino acid substitutions at M2576.40 lead to limited constitutive activity but only M257N6.40 and M257S6.40 reach at least half the level of M257Y6.40 (17). These two side chains could, with some small rearrangements in the protein, form hydrogen bonds with R1353.50, but would lack the aromatic–aromatic interactions with Y3067.53 and Y2235.58, which might explain their lower effect on constitutive activity. Thus, the tyrosine at position 2576.40 seems to be an optimal fit to stabilize the open G protein binding site.

Environment and Conformation of Retinal.

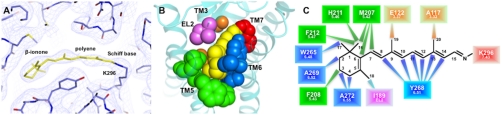

During structure determination of the light activated M257Y/GαCT complex, retinal could be readily localized in its binding pocket (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. 3). The retinal β-ionone ring, the polyene backbone and the Schiff base including the K2967.43 side chain in TM7 could be clearly positioned (Fig. 3A). Strong density between the C15 atom of the retinal and the amine of K2967.43 indicates a homogenous Schiff base bond compatible with the 15-anti-conformation, in agreement with FTIR spectroscopic characterizations of metarhodopsin-II (25).

Fig. 3.

Conformation of all-trans-retinal in the M257Y/GαCT structure. The 2Fo-Fc density map contoured at 1σ (A, blue mesh) shows clear uninterrupted density for all-trans-retinal including the covalent bond to K2967.43 that is characteristic for the active metarhodopsin-II state. The retinal binding pocket (B, C, defined as residues with interatomic distances to the retinal ≤ 4 Å) is dominated by hydrophobic van der Waals contacts between the β-ionone ring and four amino acids in TM5 (green), three amino acids in TM6 (blue), and one in EL2 (violet). The polyene part of the retinal is covalently bound to K2967.43 in TM7 (red) and stacked against Y2686.51 in TM6 (blue), while the two amino acids in TM3 (orange) directly interact with the C19 and C20 methyl groups.

We initially positioned the β-ionone ring in the same orientation as in ground state rhodopsin (3) and the batho (5) and lumi (6) early intermediates—i.e., with the methyl groups C16 and C17 pointing toward the extracellular side and C18 toward the cytoplasmic side, and as proposed in previous NMR studies (26). However, rotation of retinal along its axis by nearly 180° with respect to the lumi state resulted in a better-defined position of the C19 and C20 methyl groups of the polyene backbone and of the C16, C17, C18 methyl groups of the β-ionone ring. This retinal rotation is accompanied by relaxation from a bent conformation in the batho and lumi states to a nearly relaxed planar conformation. A simultaneous rotation of the β-ionone ring and the polyene backbone is required to maintain the 6-s-cis-bond, in agreement with solid state NMR data that indicate this orientation of the ring in both metarhodopsin-I (27) and metarhodopsin-II (26). Moreover, this orientation agrees better with the NMR-derived distance constraints (26). Altogether, the position of retinal in our structure of the light activated constitutively active rhodopsin mutant M257Y6.40 agrees very well with the retinal position obtained from opsin crystals soaked with all-trans-retinal (11).

Isomerization and rotation of retinal results in a 4 Å translocation of the β-ionone ring into the cleft between TM5 and TM6 (Fig. 3 B and C and Movie S1). Further ligand-protein contacts are established with TM3 and extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) in addition to the Schiff base to TM7. Altogether the rotated retinal shares a contact surface of approximately 300 Å2 with the protein and occupies a binding pocket with a volume of 850 Å3 (SI Appendix, Fig. 4). Ground state rhodopsin, by comparison, has a much more compact binding pocket, where 11-cis-retinal buries approximately 230 Å2 of the protein (3) and occupies 660 Å3. Thus, retinal isomerization—i.e., conversion from the inverse agonist to the agonist form—results in an increase in the volume of the binding pocket. In rhodopsin, this increase is already present in lumirhodopsin (6) (binding pocket volume of approximately 890 Å3) and results from relocation of bulky side chains in the earliest steps of activation, primarily M2075.42. Interestingly, retinal isomerization results in a weakening of the TM2-TM6-TM7 interface near the binding pocket, due to a local structural rearrangement at the backbone of the G892.56–G902.57 motif in TM2 that is transmitted to M862.53. This, together with the displacement of S2987.45 and W2656.48, results in the creation of a gap between the binding pocket and the cluster of intramolecular water molecules (SI Appendix, Fig. 4).

In summary, retinal isomerization is accompanied by an increase in the retinal-protein contacts with TM5 and TM6 (SI Appendix, Fig. 5), the two helices that undergo the largest conformational changes during activation, and by a decrease in the contacts to TM3. In addition, there is an increase in the contact surface of retinal with ECL2, which has also been proposed to be involved in rhodopsin activation (28).

Discussion

Crystallization of Metarhodopsin-II from Light Activated Rhodopsin.

Obtaining the structure of the only nonrhodopsin GPCR that has been crystallized in a fully activated state, the β2 adrenergic receptor, required a formidable effort of protein engineering, including the use of high-affinity and very low off-rate synthetic agonists combined with posttranslational modifications, truncation of flexible termini, creation of T4 lysozyme fusion chimeras, and binding of specific nanobodies (29, 30). On the other hand, the crystal structure of the active state of rhodopsin was recently obtained using protein purified from natural sources (11). However, in this case, the active ligand-receptor complex was created by soaking opsin crystals with the agonist all-trans-retinal. In comparison, we have been able to create the active ligand-receptor complex by illumination of rhodopsin; i.e., by the natural activation mechanism. This has been possible by using the constitutively active M257Y6.40 mutant combined with two functionally neutral but stabilizing cysteines (15, 16). Thus, we have been able to work with the complete polypeptide including intact posttranslational modifications and only three mutations.

Constitutively active mutants predispose rhodopsin to the active conformation, and allow all-trans-retinal to bind as a diffusible agonist (17, 31). This allows all-trans-retinal to accommodate stably into the retinal binding site, in contrast to inactive wild-type opsin. Similar cases in which higher basal activity or binding of the G protein increases affinity for agonists are well documented, for example in the β2 adrenergic receptor (32). In agreement with previous reports on the M257Y6.40 single mutation (17), we demonstrate that the stabilized M257Y6.40 mutant binds all-trans-retinal in the correct orientation to form a covalent bond to the receptor (Figs. 1B and 3A) like in metarhodopsin-II. The stabilized M257Y6.40 mutant furthermore expresses the same levels of G protein activation as wild-type metarhodopsin-II, both in presence of all-trans-retinal, as well as after light-activation of the ground state reconstituted with 11-cis-retinal. Nevertheless, we had two reasons to prefer the light activated form to cocrystallizing constitutively active opsin with all-trans-retinal. First, it keeps the receptor in the most stable ground state during purification and minimizes possible detergent effects on the more unstable active state. Second, light activation just before crystallization helps avoiding possible problems with nonphysiological binding of retinal and ensures that the light activated receptor is as close as possible to metarhodopsin-II. We further verified that the M257Y6.40 mutant could be activated under crystallization conditions using light-induced FTIR difference spectroscopy (SI Appendix, Fig. 2). A more comprehensive spectroscopic characterization will be published elsewhere.

As intended, crystallization of light-activated constitutively active M257Y6.40 allowed us to determine a structure with major hallmarks of the fully active metarhodopsin-II state. The position of retinal is in good agreement with spectroscopic measurements (25, 26) In addition, the conformational changes of TM5 and TM6 are in very good agreement with double electron-electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy (33) and cross-linking experiments (34), and result in the opening of a specific binding interface to the C-terminus of the G protein. Thus, we conclude that our structure indeed closely resembles the fully activated receptor metarhodopsin-II.

The M257Y6.40 Mutation Selectively Stabilizes the G Protein Binding Site.

Constitutively active mutants are ubiquitously found among GPCRs and many of them are related to pathologic outcomes (12). Many wild-type GPCRs have intrinsically high levels of basal activity with important functional implications [e.g., the melanocortin MCR1 and MCR4 receptors (12)], and different levels of basal activity may also contribute to subtype specificity. Due to the relevance of constitutive activity in GPCR function, the study of its structural basis is very relevant.

Methionine 2576.40 is part of a highly conserved patch of hydrophobic residues close to the G protein binding site and located between the highly conserved E(D)RY motif in TM3 and the NPxxY motif in TM7. Mutations at position 6.40 have an impact in several GPCRs. For instance, in the A2a adenosine receptor, mutations of position 6.40 and other nearby residues lead to a strong stabilizing effect on the agonist and antagonist bound forms of this receptor (35). Changes in position 6.40 have also been shown to cause strong constitutive activity in the 5-HT2A serotonin (36) and the histamine H1 receptors (37). It is then likely that modifications in the packing of TM2-TM3-TM6 are related to constitutive activity in many GPCRs (12).

Rhodopsin has evolved as dim light sensor, which requires a virtually nonexistent level of basal activity (i.e., “background noise”). In many ways, constitutively active mutants that increase this basal activity transform the highly specialized photoreceptor back into a more general GPCR that is activated by diffusible agonists, demonstrating how relatively minor modifications can adapt a given GPCR to its specific function.

Structures of the active rhodopsin state solved in presence (9, 11) and absence (7, 8) of the retinal agonist are very similar. This is likely also the case for constitutively active mutants that increase the fraction of active opsin but do not change the activity of the retinal-bound metarhodopsin-II state. Indeed it has been suggested that constitutive activity of the M257Y6.40 mutant originates from interference of the helix packing in the ground state (3). Mutations of M2576.40 likely reduce the energy barrier between the active and inactive states by disturbing the hydrophobic barrier between the intramolecular water-mediated hydrogen bond network and the cytoplasmic side (SI Appendix, Fig. 4) that prevents helix movement until this is triggered by chromophore isomerization and translocation of W2656.48. This relatively nonspecific effect is supported by the fact that most amino acid substitutions at position 2576.40 lead to constitutive activity (17). However, our structure shows that, in addition to destabilization of the cytoplasmic hydrophobic barrier, the tyrosine side chain is ideally positioned to interact with Y2235.58 in TM5, Y3067.53 of the NPxxY and R1353.50 of the E(D)RY motif (Fig. 2), which reinforces the exceptionally high constitutive activity of the M to Y substitution. Residue Y2235.58 in TM5 is highly conserved among GPCRs, yet, in the structure of ground state rhodopsin it is positioned in an inconsequential position pointing toward the membrane. Only active state structures reveal a significant conformational change of this residue that repositions it close to the ionic lock region in direct hydrophilic interaction with R1353.50. Similarly, Y3067.53 swings into the cleft left by the rearrangement of TM6 during activation. In the active state, both Y2235.58 and Y3067.53 participate in an extended hydrogen bond network between the retinal and G protein binding sites. R1353.50 is part of the ionic interaction between the E1343.49/R1353.50 pair in the E(D)RY motif of TM3 and E2476.30 in TM6. In the so-called second proton switch of rhodopsin activation (38), protonation of E1343.49 releases R1353.50 from its warped conformation in the ground state, releasing the ionic TM3-TM6 interaction and facilitating the outward movement of TM6, which allows binding of the G protein. R1353.50 directly participates in binding of the GαCT peptide and is stabilized by a water molecule and Y2235.58. In summary, our structure shows that M257Y6.40 stabilizes the G protein binding site through interactions with three residues that are critical for receptor activation (Fig. 2). Our structure furthermore provides an example of how a single point mutation can dramatically change activation characteristics of a receptor without a major structural alteration of the active state.

Activation of both rhodopsin and the β2 adrenergic receptor involves a common transmission switch in the TM3-TM5-TM6 interfaces that results in conformational changes near the G protein binding site (39). Despite these similarities, the structures of metarhodopsin-II bound to GαCT show a smaller relocation of TM6 (6 Å, measured at 6.33) than in the β2 adrenergic receptor-nanobody complex (8 Å) (29) and the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein-nanobody complex (10 Å) (30). Future work will clarify whether this increased conformational change is due to binding of the nanobody, formation of new interactions between the activated receptor and the G protein or fundamental differences between the activation mechanisms of these two receptors.

Light-Induced Activation of Rhodopsin.

Our structure shows several rearrangements in the retinal binding pocket that couple isomerization of the inverse agonist 11-cis-retinal into the full agonist all-trans-retinal to conformational changes of the protein upon activation (SI Appendix, Fig. 4). Internal proton transfer from the protonated retinal Schiff base to its counterion E1133.28 in the transmembrane domain (38, 40) is one of these activation switches. Our metarhodopsin-II structure shows an increased distance of 6.6 Å between the Schiff base nitrogen and the Cδ atom of E1133.28 with respect to the ground state (3). This change is in good agreement with the proposed opening of this activation switch (40) and other crystal structures of active rhodopsin states (7–9, 11).

Another rearrangement is the translocation and rotation of the β-ionone ring into a cleft between TM5 and TM6, the two helices that undergo the largest conformational changes during activation. Our structure shows a series of side chain rearrangements and small local structural changes in TM5 that result in a weakening of the TM3-TM5 interface and also in a displacement of ECL2, as has been found by NMR spectroscopy (26, 28). Translocation of the β-ionone ring furthermore releases W2656.48 that, in ground state rhodopsin, is trapped in a U-shaped bend formed by the 11-cis-retinal and the side chain of K2967.43. Against earlier models, the tryptophan does not change rotamer during this transition. However, transition of W2656.48 leads to rearrangement of a water-mediated hydrogen bond network that in the active state reaches from the retinal to the G protein binding site and facilitates the large-scale rigid-body tilt of TM6 (9). The nature of the residues involved in regulating the intramolecular water pockets is highly conserved in Class A GPCRs. Thus, these rearrangements are likely to be conserved throughout the family, constituting a specific activation pathway through TM2/TM7 (41).

The rearrangements involving the β-ionone are very similar to the ones found in the structure of E113Q3.28 rhodopsin, where retinal is noncovalently bound (SI Appendix, Fig. 3). Full activation of rhodopsin, however, requires an intact Schiff base bond to the receptor (42, 43), which seems to require the rotation of the chromophore during activation (11). Interestingly, this rotation is not observed in bacteriorhodopsin, another well-studied retinal binding 7TM protein. In contrast to the proton pump bacteriorhodopsin, the GPCR rhodopsin does not return to its ground state after activation but disassembles into opsin and all-trans-retinal. Thus, rotation and relocation of retinal within a tight binding pocket may be required for Schiff base hydrolysis and subsequent deactivation of the receptor.

Conclusions

Here we present the crystal structure of the light activated constitutively active rhodopsin mutant M257Y6.40 in complex with the C-terminal end of the G protein α-subunit. Comparison with biochemical, spectroscopic, and structural data suggests that our structure is very close, if not identical, to metarhodopsin-II obtained by the native activation mechanism. The observed rearrangements are nearly identical whether rhodopsin is activated by light and then crystallized or if all-trans-retinal is soaked into preformed opsin crystals (11). This finding emphasizes the resemblance of light-induced activation in rhodopsin to activation of other GPCRs by diffusible agonists and supports ligand soaking as a valuable approach for GPCR structure determination. The presented structure furthermore helps us to understand constitutively activating mutations on a structural level and by extension variable basal activity levels among different members of the GPCR superfamily. In many cases, constitutive activity originates from disruptions in helix-helix interactions and a resulting increased conformational flexibility of the receptor. Our crystal structures of the constitutively active E113Q3.28 and M257Y6.40 rhodopsin mutants provide two examples in which the molecular basis for constitutive activity is more specific. It thus appears necessary to investigate the molecular causes of constitutive activity on a case-to-case basis. This is especially true for constitutively active mutants that cause hereditary diseases like retinitis pigmentosa (RP) or congenital stationary night blindness where specific molecular causes may open the possibility for directed intervention by small molecular drugs.

Methods

Bovine rhodopsin containing the stabilizing N2C/D282C and M257Y6.40 mutations was expressed in HEK293S-GnTI- cells with homogenous N-glycosylation. Detergent solubilized receptor was reconstituted with 11-cis-retinal and purified. Activation was assayed by the amount of radioactively labeled GTPγ35S bound to the G protein transducin. For crystallization, reconstituted ground state rhodopsin was mixed with dried brain lipid extract, supplemented with the GαCT peptide (ILENLKDCGLF) and selectively activated using a > 515 nm long pass filter. Crystals were grown, harvested, and frozen under dim red light. Data was collected using a focused microbeam. Phases were obtained by molecular replacement using the polypeptide of the E113Q mutant (9) as search model. Full methods are available as supplementary material (SI Appendix).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Fritz Winkler for discussions on crystallographic refinement. We thank Reiner Vogel for the FTIR spectroscopic characterization under crystallization conditions. We thank the staff at the Macromolecular Crystallography group at the Swiss Light Source (SLS) for excellent support during data collection. We are grateful for financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Grant 31003A_132815 and the ETH Zürich within the framework of the National Center for Competence in Research in Structural Biology Program (to X.D, J.S. and G.F.X.S.). The work was further financially supported by National Institutes of Health Grant EY007965 (to D.D.O.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 4A4M).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1114089108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ye S, et al. Tracking G-protein-coupled receptor activation using genetically encoded infrared probes. Nature. 2010;464:1386–1389. doi: 10.1038/nature08948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palczewski K, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Villa C, Schertler GF. Structure of bovine rhodopsin in a trigonal crystal form. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1409–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Standfuss J, et al. Crystal structure of a thermally stable rhodopsin mutant. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamichi H, Okada T. Crystallographic analysis of primary visual photochemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:4270–4273. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamichi H, Okada T. Local peptide movement in the photoreaction intermediate of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12729–12734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601765103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JH, Scheerer P, Hofmann KP, Choe HW, Ernst OP. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454:183–187. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheerer P, et al. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature. 2008;455:497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature07330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Standfuss J, et al. The structural basis of agonist-induced activation in constitutively active rhodopsin. Nature. 2011;471:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature09795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhukovsky EA, Oprian DD. Effect of carboxylic acid side chains on the absorption maximum of visual pigments. Science. 1989;246:928–930. doi: 10.1126/science.2573154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choe HW, et al. Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature. 2011;471:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature09789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smit MJ, et al. Pharmacogenomic and structural analysis of constitutive G protein-coupled receptor activity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:53–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao VR, Cohen GB, Oprian DD. Rhodopsin mutation G90D and a molecular mechanism for congenital night blindness. Nature. 1994;367:639–642. doi: 10.1038/367639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson PR, Cohen GB, Zhukovsky EA, Oprian DD. Constitutively active mutants of rhodopsin. Neuron. 1992;9:719–725. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90034-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Standfuss J, Zaitseva E, Mahalingam M, Vogel R. Structural impact of the E113Q counterion mutation on the activation and deactivation pathways of the G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie G, Gross AK, Oprian DD. An opsin mutant with increased thermal stability. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1995–2001. doi: 10.1021/bi020611z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han M, Sakmar TP. Assays for activation of recombinant expressed opsins by all-trans-retinals. Methods Enzymol. 2000;315:251–267. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)15848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamm HE, et al. Site of G protein binding to rhodopsin mapped with synthetic peptides from the alpha subunit. Science. 1988;241:832–835. doi: 10.1126/science.3136547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin EL, Rens-Domiano S, Schatz PJ, Hamm HE. Potent peptide analogues of a G protein receptor-binding region obtained with a combinatorial library. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:361–366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: High-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrand PW, et al. A ligand channel through the G protein coupled receptor opsin. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritze O, et al. Role of the conserved NPxxY(x)5,6F motif in the rhodopsin ground state and during activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2290–2295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435715100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogel R, et al. Functional role of the “ionic lock”—An interhelical hydrogen-bond network in family A heptahelical receptors. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goncalves JA, et al. Highly conserved tyrosine stabilizes the active state of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19861–19866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009405107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahalingam M, Vogel R. The all-trans-15-syn-retinal chromophore of metarhodopsin III is a partial agonist and not an inverse agonist. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15624–15632. doi: 10.1021/bi061970n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahuja S, et al. Location of the retinal chromophore in the activated state of rhodopsin*. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10190–10201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805725200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spooner PJ, et al. Conformational similarities in the beta-ionone ring region of the rhodopsin chromophore in its ground state and after photoactivation to the metarhodopsin-I intermediate. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13371–13378. doi: 10.1021/bi0354029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahuja S, et al. Helix movement is coupled to displacement of the second extracellular loop in rhodopsin activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:168–175. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen SG, et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the beta(2) adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011;469:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen SG, et al. Crystal structure of the beta(2) adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen GB, Oprian DD, Robinson PR. Mechanism of activation and inactivation of opsin: Role of Glu113 and Lys296. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12592–12601. doi: 10.1021/bi00165a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao XJ, et al. The effect of ligand efficacy on the formation and stability of a GPCR-G protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9501–9506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811437106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altenbach C, Kusnetzow AK, Ernst OP, Hofmann KP, Hubbell WL. High-resolution distance mapping in rhodopsin reveals the pattern of helix movement due to activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7439–7444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802515105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrens DL, Altenbach C, Yang K, Hubbell WL, Khorana HG. Requirement of rigid-body motion of transmembrane helices for light activation of rhodopsin. Science. 1996;274:768–770. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebon G, Bennett K, Jazayeri A, Tate CG. Thermostabilisation of an agonist-bound conformation of the human adenosine A(2A) receptor. J Mol Biol. 2011;409:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shapiro DA, Kristiansen K, Weiner DM, Kroeze WK, Roth BL. Evidence for a model of agonist-induced activation of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A serotonin receptors that involves the disruption of a strong ionic interaction between helices 3 and 6. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11441–11449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakker RA, et al. Constitutively active mutants of the histamine H1 receptor suggest a conserved hydrophobic asparagine-cage that constrains the activation of class A G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:94–103. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahalingam M, Martinez-Mayorga K, Brown MF, Vogel R. Two protonation switches control rhodopsin activation in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17795–17800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804541105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deupi X, Standfuss J. Structural insights into agonist-induced activation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JM, et al. Structural origins of constitutive activation in rhodopsin: Role of the K296/E113 salt bridge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12508–12513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404519101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deupi X, Kobilka BK. Energy landscapes as a tool to integrate GPCR structure, dynamics, and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:293–303. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00002.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhukovsky EA, Robinson PR, Oprian DD. Transducin activation by rhodopsin without a covalent bond to the 11-cis-retinal chromophore. Science. 1991;251:558–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1990431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuyama T, Yamashita T, Imai H, Shichida Y. Covalent bond between ligand and receptor required for efficient activation in rhodopsin. J Biol Chem. 285:8114–8121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.