Abstract

Estradiol (E2) deficiency decreases muscle strength and wheel running in female mice. It is not known if the muscle weakness results directly from the loss of E2 or indirectly from mice becoming relatively inactive with presumably diminished muscle activity. The first aim of this study was to determine if cage activities of ovariectomized mice with and without E2 treatment differ. Ovariectomized mice were 19–46% less active than E2-replaced mice in terms of ambulation, jumping, and time spent being active (P ≤ 0.033). After E2-deficient mice were found to have low cage activities, the second aim was to determine if E2 is beneficial to muscle contractility, independent of physical activities by the mouse or its hindlimb muscles. Adult, female mice were ovariectomized or sham-operated and randomized to receive E2 or placebo and then subjected to conditions that should maintain physical and muscle activity at a constant low level. After 2 wk of hindlimb suspension or unilateral tibial nerve transection, muscle contractile function was assessed. Soleus muscles of hindlimb-suspended ovariectomized mice generated 31% lower normalized (relative to muscle contractile protein content) maximal isometric force than suspended mice with intact ovaries (P ≤ 0.049). Irrespective of whether the soleus muscle was innervated, muscles from ovariectomized mice generated ∼20% lower absolute and normalized maximal isometric forces, as well as power, than E2-replaced mice (P ≤ 0.004). In conclusion, E2 affects muscle force generation, even when muscle activity is equalized.

Keywords: estrogen, hindlimb suspension, ovariectomy, physical activity, tibial nerve transection

estradiol [i.e., 17β-estradiol (E2)] is implicated as a factor influencing muscle strength. With the loss of E2, via removal of ovarian tissue, the force-generating capacity of hindlimb muscles in mice decreases (22). After replacement of E2, this decrement in strength fully recovers, showing that E2 is a key hormone affecting skeletal muscle function and quality (21). Those findings are substantiated by the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting an overall ∼7% greater normalized muscle strength, or muscle quality, in E2-replaced than ovariectomized rodents (8). Similarly, a meta-analysis on data from ∼10,000 postmenopausal women showed that those taking an estrogen-based hormone therapy were stronger than those not taking the treatment (8). Collectively, these results provide evidence that E2 is beneficial in enhancing muscle force production. Several mechanisms have been hypothesized to account for the detrimental effect of loss of E2 on skeletal muscle: a decrease in the fraction of strongly bound myosin during contraction (22), inhibition of Ca2+ uptake at the sarcoplasmic reticulum (37), an increase in muscle damage due to a destabilized muscle membrane (1, 32), and oxidative damage (27). It is possible that any or all of these proposed mechanisms may contribute to the force-generating decrements in muscle when E2 is diminished.

It is also conceivable that any or all of the effects of E2 on muscle are not direct effects but, rather, are secondary to an estrogenic effect on some nonskeletal muscle tissue or cell. A notable systemic effect of E2 in rodents is its strong influence on physical activity, particularly voluntary wheel running (7, 14, 24, 26, 36). For example, ovariectomized mice ran ∼80% less than ovary-intact mice, but within 3 days of E2 replacement, ovariectomized mice rebounded to a running level equivalent to that of ovary-intact mice (7). Similarly, ovariectomized mice treated with tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, ran distances comparable to those of ovariectomized mice replaced with E2 (7). The extent to which circulating E2 levels influence physical activities other than voluntary wheel running, such as typical activities in a cage, is not completely known. There is limited evidence showing reduced ambulatory activity in the dark by ovariectomized compared with ovary-intact mice, with no difference during the photoperiod (28). Cage activities are important to consider because it is possible that E2-deficient mice become less active in their cages and that reduced activity, such as rearing, jumping, and ambulating, causes all or part of the ovariectomy-induced muscle weakness. Thus the first aim of the present work was to determine if E2 deficiency in female mice adversely affects normal cage activity.

Upon finding that cage activities were reduced in ovariectomized mice, we sought to address the second aim of this work, which was to determine if E2 is beneficial to muscle force generation, fatigue resistance, and power independent of physical and muscle activities. We used hindlimb suspension and unilateral tibial nerve transection to control muscle loading and activity, respectively, at constant low levels in ovariectomized mice with and without E2 replacement. We hypothesized that, under the condition of equalized activity and loading, E2 deficiency would still cause detrimental effects on muscle contractile function.

METHODS

Animals.

Female C57BL/6J mice, 3–5 mo of age, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). This age range was selected because regular estrous cycling is known to occur between 3 and 14 mo of age, and we previously reported muscle functional capacity to be at a constant level between 4 and 8 mo of age for female mice of this strain (23, 25). Upon arrival, mice were given 1–3 wk to acclimate to the facility, with free access to water and a phytoestrogen-free diet (2019 Teklad Global 19% Protein Rodent Diet, Harland Teklad, Madison, WI). Mice were group-housed for study I and housed individually for studies II and III. At the end of each study, mice were weighed and anesthetized by an injection of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg body wt), with supplemental doses given as required. While under anesthesia, mice were euthanized by exsanguination. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota and complied with the American Physiological Society guidelines.

Design of study I: daily cage activity of ovariectomized mice with and without E2 treatment.

At ∼14 wk of age, mice underwent ovariectomy and then were randomized into one of two groups: immediate treatment with a slow-release E2-containing pellet (OVX + E2, n = 8) or placebo pellet (OVX, n = 8). Cage activities of each mouse were measured 50–59 days after the ovariectomy procedure.

Design of study II: control of soleus muscle loading by hindlimb suspension.

At 21 wk of age, mice were randomized into one of three groups: surgical removal of ovarian tissue and immediate treatment with E2 (OVX + E2, n = 5) or placebo pellet (OVX, n = 6) or a sham operation (Sham, n = 6). After 3–5 days of recovery from surgery, all mice were hindlimb-suspended, as described previously (34). Briefly, mice were restrained, and harnesses were attached to their tails. The harness was then attached to the cage top, so that the hindlimbs could not touch the cage bedding. Mice remained suspended for 2 wk, such that the hindlimb muscles were unloaded for all mice.

At the end of the 2-wk suspension period, the soleus muscles from both limbs and the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle from one limb were analyzed in vitro for contractility. The soleus muscle is affected by hindlimb suspension, as indicated by a mass loss of ∼40% compared with weight-bearing mice (34). The EDL muscle is less affected by hindlimb suspension but was studied because previous work showed that contractile functions of the soleus and EDL muscles are affected by E2. In addition to contractile measurements (see below), a fatiguing contraction protocol was conducted on the soleus muscles, because of effects of sex on fatigue (10), with most hypotheses linking this sex difference to sex hormones. After the in vitro contractility analyses, muscles were weighed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Design of study III: control of soleus muscle activity by denervation.

At 14 wk of age, all mice underwent ovariectomy and tibial nerve transection and simultaneously received a pellet, either E2 (OVX + E2, n = 10) or placebo (OVX, n = 10). After 2 wk of soleus muscle denervation and E2 manipulation, the mice were anesthetized. Soleus muscles from both limbs were analyzed in vitro for contractile function. In addition, a protocol assessing the force-velocity relationship was conducted. This protocol was selected because of previous reports that E2 affected maximal shortening velocity (Vmax) (22) and myofibrillar ATPase (38). EDL muscles were not assessed because study II showed that 2 wk of hormone manipulation was not long enough to significantly affect contractility of EDL muscle. Soleus muscles were weighed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C immediately following the in vitro contractile analyses.

E2 manipulation and related assessments common to all studies.

In studies I–III, ovariectomy and sham operations were conducted as previously described (22). For the ovariectomy procedure, mice were initially anesthetized in an induction chamber using isoflurane; anesthesia was maintained by inhalation of 1.75% isoflurane mixed with oxygen by mask at a flow rate of 200 ml/min. Sham-operated mice underwent the same protocol, but no ovarian tissue was removed. While still under anesthesia, 0.18-mg, 60-day slow-release E2 or placebo pellets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) were implanted at the base of the neck in ovariectomized mice. All mice were treated with 0.15 μg of buprenorphine subcutaneously ∼5 min after end of the surgery.

Blood was collected by facial vein bleed prior to any surgical procedures and/or during exsanguination at the end of a study. Plasma was separated and stored at 4°C for analysis of circulating plasma E2. Circulating plasma E2 levels for mice in study I were measured by ELISA [RE50241, Immuno Biological Laboratories (IBL), Minneapolis, MN]. A diethylether extraction procedure as directed by IBL was carried out before the ELISA to concentrate the mouse plasma. The assay was then performed following the manufacturer's specifications. For studies II and III, an estradiol ELISA kit (KA0234, Abnova) was used following the manufacturer's specifications. Data for the standards were fit using a four-parameter logistic curve fit. It was necessary to switch to the Abnova estradiol assay because the IBL kit used in study I had been discontinued. Circulating E2 levels were measured as a marker of successful ovarian hormone depletion and replacement. The uteri from each mouse in studies II and III were dissected and weighed as a secondary marker of E2 status.

Physical activity assessment.

Cage activity of individual mice in study I was monitored for 24 h using open-field activity chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) (15). Photo beam arrays in the chamber register an activity count and duration each time one or more of the beams is disrupted. It is important to recognize that an “activity count” represents any single photo beam break. Because multiple photo beams may break with one jump, the total jump count does not represent the actual number of times a mouse jumps. Activity data were acquired using Activity Monitor version 5 software (Med Associates) with a box size set to “3” (4.8 cm2); this box size was established to calculate movement and delay and to filter the data, such that stereotypic movements are not counted as ambulation. Stereotypic movement is considered movement contained within the 4.8-cm2 box, for example, while the mouse is grooming or eating. Immediately prior to measurement of activity, each mouse was familiarized with the activity-monitoring cage by spending 24 h in a mock chamber.

Tibial nerve transection.

Immediately after the pellet implantation, while still under isoflurane anesthesia, all mice in study III underwent transection of the left tibial nerve. The mouse was positioned in right lateral recumbency, and the left foot was stabilized for the duration of the surgery. Under aseptic conditions, an ∼15-mm incision was made on the skin parallel and slightly posterior to the femur. Then an incision was made in the biceps femoris muscle, in line with the muscle fiber orientation, directly under the skin incision. The flaps of biceps femoris muscle were retracted, exposing the common peroneal and tibial nerves. Care was taken to dissect the tibial nerve from surrounding musculature, connective tissue, and fat. A 7-0 sterile silk suture was used to make a knot on the most distal portion of the tibial nerve. The nerve was cut just distal to the knot and then retracted. The nerve was cut as proximal as possible, such that a ≥3-mm segment of nerve was removed. The biceps femoris muscle flaps were sutured together and the skin incision was closed, both with use of 6-0 silk suture. The left tibial nerve of all mice was cut and removed, while the right limb remained intact and served as the intra-animal control.

In vitro assessment of skeletal muscle contractility.

Procedures used for isolation and testing of soleus and EDL muscles have been described previously (23, 34). Contractile characteristics that were measured in all studies included maximal isometric tetanic force (Po) and active stiffness. Active stiffness is an indirect estimate of myosin strongly bound to actin during contraction (6, 30). Muscle length from proximal to distal myotendinous junction was measured using digital calipers after the muscles were set to their anatomic resting length. Fiber lengths were calculated as 71 and 44% of the measured muscle length for the soleus and EDL muscles, respectively (3, 19). Normalized Po was calculated as Po divided by the ratio of contractile protein content (sum of myosin heavy chain and actin contents) to fiber length. Contractile protein content, rather than physiological cross-sectional area, was used to adjust Po for muscle size because ovariectomy causes an increase in nonprotein mass that inflates cross-sectional area (22).

In study II, soleus muscles were subjected to a protocol employing a bout of fatiguing contractions that was initiated 2 min following the force and stiffness measurements (9). Muscles were subjected to 1-s tetanic contractions, at 150 V and 40 Hz, at a rate of 12 tetani/min for 5 min, for a total of 60 contractions. For the 20 min following this test protocol, maximal tetanic contractions were done at 5-min intervals to assess the extent of recovery. Because soleus muscles were atrophied from the 2-wk suspension and required delicate dissection, muscles from both limbs of each mouse were tested. The soleus muscle with the higher Po was used in all statistical analyses (the overall results were not different if both muscles were averaged together).

In study III, soleus muscles completed a protocol assessing the force-velocity relationship by measurement of 12 shortening velocities using quick releases from Po to given afterloads that corresponded to 5–50% of Po (22). The muscle's Vmax and maximal power were determined by fitting the data as a hyperbolic-linear curve using Table Curve 2D (version 5.0, Systat Software, Richmond, CA) (3, 4, 13). Maximal power was normalized by the ratio of contractile protein content to fiber length, in parallel to normalized Po.

Determination of contractile protein content.

Soleus and EDL muscles that were tested in vitro for contractility were subsequently homogenized and electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels to determine contents of actin and myosin heavy chain (22).

Statistical analysis.

Independent Student's t-tests were used to determine whether there were differences in 1) cage activities between ovariectomized mice with and without E2 treatment in study I and 2) plasma E2 and uterine masses between mice with and without E2 in studies II and III. Body masses were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (treatment × time) for all studies. Muscle contractile parameters were evaluated using independent Student's t-tests in study II and two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs (limb × treatment) in study III. Pearson's correlations were used to determine if cage activities were associated with plasma E2 levels. Effect sizes for correlations of cage activity data were calculated by conversion of the correlation to Fisher's z scale (2). All statistical analyses were done using SigmaStat version 3.5 (Systat Software). Significance was accepted with an α level of 0.05. Values are means (SD).

RESULTS

Effects of E2 manipulation common to all studies.

Body mass of rodents may be affected by ovarian hormone status. At the end of the ∼60-day hormone manipulation in study I, body mass was 13% greater in OVX than OVX + E2 mice (Table 1). In study II, OVX mice gained more body mass during the 2-wk intervention than did the Sham mice [19.4% (SD 3.7) vs. 11.2% (SD 3.1), P < 0.001; Table 1]. The OVX + E2 mice in study II lost body mass during the first 2–5 days of treatment. In study III, mice gained ∼14% body mass over the 2-wk study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body mass before and following 60 (study I) or 14 (studies II and III) days of hormone manipulation

| Body Mass, g |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | Pre | Post | Statistical Findings |

| Study I | ||||

| OVX + E2 | 8 | 20.2 (1.9) | 21.9 (1.3)* | E2 × time interaction (P = 0.004) |

| OVX | 8 | 19.3 (1.0) | 24.7 (1.1)*† | |

| Study II | ||||

| Sham | 6 | 19.7 (0.8) | 21.6 (1.3)† | |

| OVX | 6 | 19.8 (0.9) | 24.5 (0.9)*† | E2 × time interaction (P = 0.007) |

| OVX + E2 | 5 | 19.3 (1.1) | 17.4 (0.6)*‡ | |

| Study III | ||||

| OVX + E2 | 10 | 19.7 (1.3) | 22.5 (0.9) | Main effect of time (P < 0.001) |

| OVX | 10 | 19.6 (0.9) | 22.4 (1.1) | |

Values are means (SD). OVX, ovariectomized; E2, 17β-estradiol. Data within each study were analyzed by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA (estradiol by time, with time being the repeated factor).

Significantly different from Pre within group.

Significantly different from OVX + E2 at same time point.

Measurement obtained 2-5 days following E2 treatment.

The effectiveness of ovariectomy and E2 replacement was evaluated by measurement of plasma E2 levels and uterine mass. The mean plasma E2 levels of OVX and OVX + E2 mice in study I were 13.8 pg/ml (SD 3.1) and 38.9 (SD 7.4) at the end of the 60-day study (P ≤ 0.001). Prior to randomization into surgical procedures in study II, circulating plasma E2 of all mice averaged 25.1 pg/ml (SD 12.8). At death, Sham mice had circulating levels of 30.7 pg/ml (SD 13.1), while four of six of the OVX mice had plasma levels below the detection level of the assay, i.e., <10 pg/ml. The average of the other two OVX mice was 18.5 pg/ml (SD 5.4). The uterus atrophies with estrogen deprivation (20), and indeed there was a substantial difference between OVX and Sham mice in study II [24.7 mg (SD 8.3) and 71.5 (SD 25.9), respectively, P = 0.002], further confirming successful reduction of estrogens. After 2 wk of denervation and E2 manipulation in study III, circulating E2 levels averaged 220.0 pg/ml (SD 116.8) in OVX + E2 mice, while E2 was below the detection level of the assay in 7 of the 10 OVX mice; the average of the other 3 OVX mice was 23.0 pg/ml (SD 10.2). Uterine mass averaged 25.5 mg (SD 3.4) and 148.1 (SD 21.7) for the OVX and OVX + E2 mice, respectively (P < 0.001).

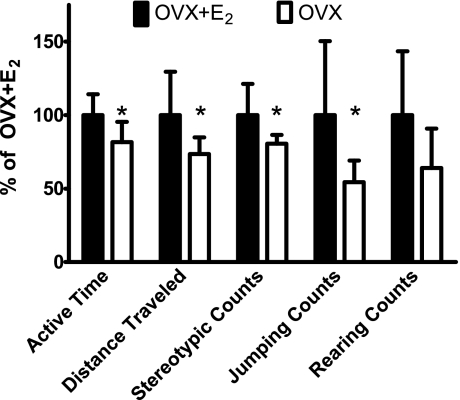

Study I: daily cage activity of OVX + E2 and OVX mice.

To test the hypothesis that mouse physical activity was diminished with E2 deficiency, several parameters of daily cage activities were measured in OVX and OVX + E2 mice (Fig. 1). During a 24-h period, the OVX mice spent 19% less time being active than did the OVX + E2 mice (P = 0.020). This percentage equates to a difference of 60 min of physical activity per day: 263 min (SD 45) and 323 (SD 46) for OVX and OVX + E2 mice, respectively. Ambulation, or distance traveled over 24 h, was ∼30% less in OVX than OVX + E2 mice [426 m (SD 65) vs. 580 (SD 171), P = 0.033]. OVX mice did ∼20% fewer stereotypic movements [41,964 counts (SD 3,054) vs. 52,019 (SD 11,096)]; i.e., these mice had fewer beam breaks while grooming or eating (P = 0.027); furthermore, OVX mice jumped 46% less than OVX + E2 mice [1,757 counts (SD 469) vs. 3,226 (SD 1,624), P = 0.028]. Additionally, OVX mice tended to rear, or go onto their hindlimbs, less than OVX + E2 mice [3,634 counts (SD 538) vs. 5,677 (SD 933), P = 0.072].

Fig. 1.

Daily cage activities of ovariectomized mice treated with placebo (OVX) relative to ovariectomized mice treated with 17β-estradiol (OVX + E2). All data [means (SD), n = 8 per group] were collected ∼55 days after ovariectomy. “Count” is a measure of 1 single photo beam break, and stereotypic counts are movements while the mouse is contained within the computer-generated box. *Significantly different from OVX + E2.

Correlational analyses were performed to determine if cage activities were associated with plasma E2 levels. Active time was correlated with plasma E2 levels (r = 0.503, P = 0.047). Ambulation, jumping, rearing, and stereotypic activity were not significantly correlated with plasma E2 (P = 0.072–0.188), although trends existed for mice with lower E2 levels to be less active. Effect sizes for correlations were calculated and found to be “large” (5). For example, effects sizes for correlations between plasma E2 levels and ambulation distance, rearing, and jumping were 1.04–1.16.

Study II: control of soleus muscle loading by hindlimb suspension.

In attempt to equalize the use and loading of the soleus and EDL muscles in mice with and without normal levels of circulating E2, all mice in study II were hindlimb-suspended. The five OVX + E2 mice had to be euthanized 2–5 days following hindlimb suspension. Once suspended, these OVX + E2 mice ate ∼70% less chow than the OVX or Sham mice; these mice lost ∼13% of their body mass during those 2–5 days (Table 1). Since all mice underwent comparable anesthesia, surgeries, and hindlimb suspension, stresses caused by these individual interventions were likely not responsible; the E2 treatment was the differentiating intervention and, when combined with hindlimb suspension, may have placed excessive stress on the animals. Nonetheless, to move forward with the question of direct vs. indirect effects of ovarian hormones on skeletal muscle, the Sham and OVX groups were compared. The caveat of this study design is that any difference between Sham and OVX mice could not be attributed solely to E2 because ovariectomy results in more than the loss of this single ovarian hormone.

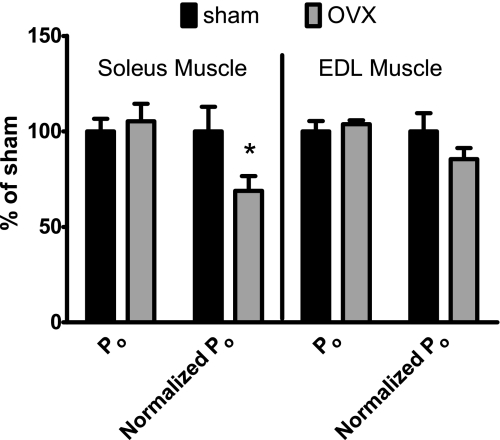

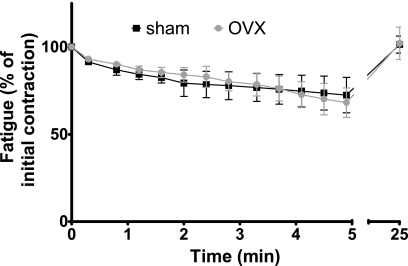

Two weeks of ovarian hormone deficiency in hindlimb-suspended mice resulted in a modest decrement in soleus muscle contractility relative to suspended mice with normal levels of ovarian hormones (Fig. 2). Absolute Po for soleus muscle was not affected by ovarian hormone status [83.6 m·N (SD 13.5) and 84.8 (SD 18.6) in Sham and OVX mice, respectively, P = 0.907; Fig. 2]. Normalized Po of soleus muscle was ∼30% lower in OVX than Sham mice [0.178 N·cm·mg−1 (SD 0.05) vs. 0.268 (SD 0.08), P = 0.049; Fig. 2]. Two weeks of ovarian hormone manipulation did not result in significant effects on EDL muscle contractility (Fig. 2). Absolute and normalized Po of EDL muscles were not different between Sham and OVX mice [294.5 m·N (SD 39.5) and 301.8 (SD 16.3) and 0.210 N·cm·mg−1 (SD 0.05) and 0.175 (SD 0.02), respectively, P ≥ 0.168]. Ovarian hormone status did not affect active stiffness, a marker of myosin-actin strong binding, of soleus or EDL muscles (P ≥ 0.197). Active stiffness was 229.8 N/m (SD 24.6) and 194.8 (SD 51.3) for the soleus muscle and 393.2 (SD 53.2) and 371.1 (SD 33.2) for the EDL muscle for the Sham and OVX mice, respectively. Nor was there any indication that fatigue of the soleus muscle was affected by ovarian hormone status. Soleus muscles from both groups lost ∼30% of their force-generating capacity from the 1st to the 60th contraction (P = 0.947; Fig. 3). Fatigue, as opposed to injury, was confirmed because at 20 min following the 60th fatiguing contraction, Po was not different from that measured prior to the fatigue protocol (P = 0.183; Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Force-generating capacities of soleus and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles of Sham (control) and OVX mice following 2 wk of hindlimb unloading [means (SD), n = 6 per group]. Normalized maximum isometric tetanic force (Po) is Po divided by the ratio of contractile protein content to fiber length. *Significantly different from sham.

Fig. 3.

Force decrements and recovery from a fatiguing bout of contractions performed by soleus muscles from Sham and OVX mice following 2 wk of ovarian hormone manipulation and hindlimb unloading [means (SD), n = 5 per group]. Fatigue is calculated as percentage of force relative to force of 1st contraction of the protocol. Relative forces of every 5th contraction during the 60-contraction fatiguing protocol and a recovery index 20 min following the protocol are plotted.

The mass of soleus muscles was ∼17% greater in OVX than Sham mice (Table 2). There were no differences in soleus muscle length or total or contractile protein contents between Sham and OVX mice (Table 2), indicating that the OVX-induced increase in mass was due to fluid accumulation. The size and composition of EDL muscles were not significantly different between OVX and Sham mice (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of hindlimb suspension on soleus and EDL muscle from Sham and OVX mice

| Sham | OVX | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soleus muscle | |||

| Muscle mass, mg | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.7 (0.5) | 0.046 |

| Muscle length, mm | 10.0 (0.6) | 9.6 (0.9) | 0.388 |

| Total protein, mg/mg | 0.106 (0.02) | 0.109 (0.01) | 0.625 |

| Contractile protein, mg | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.33 (0.08) | 0.111 |

| EDL muscle | |||

| Muscle mass, mg | 8.1 (0.8) | 8.7 (0.2) | 0.112 |

| Fiber length, mm | 12.0 (0.5) | 12.16 (0.6) | 0.665 |

| Total protein, mg/mg | 0.130 (0.01) | 0.136 (0.01) | 0.422 |

| Contractile protein, mg | 0.77 (0.15) | 0.94 (0.21) | 0.130 |

Values are means (SD); n = 6 in each group. Sham-operated (Sham) and OVX mice were hindlimb-suspended for 2 wk. EDL, extensor digitorum longus. Data were analyzed by Student's t-test.

Study III: control of soleus muscle activity by denervation.

All mice in study III underwent unilateral tibial nerve transection to equalize the use of the soleus muscle, irrespective of the physical activity level of the mouse. All mice also were ovariectomized, with half of the mice receiving E2 replacement. This allowed for the direct investigation of the effect of E2 on skeletal muscle.

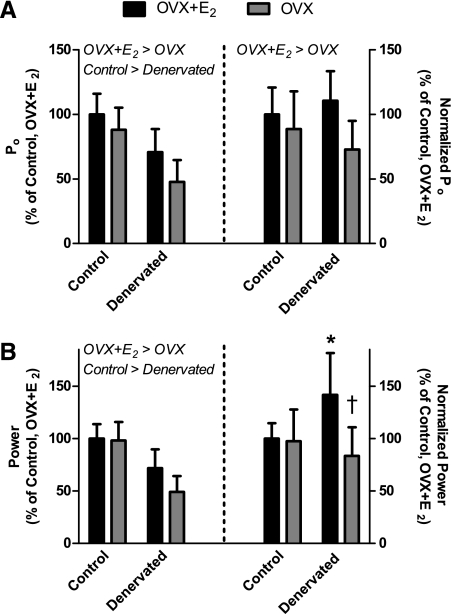

Soleus muscles from OVX mice had low capacities to generate force relative to those from OVX + E2 mice, regardless of whether the muscle was innervated (i.e., no interaction between E2 status and innervation for all variables, with the exception of normalized power; Table 3). Specifically, less absolute force was generated by soleus muscles of OVX than OVX + E2 mice (Fig. 4A, left; Table 3). More importantly, Po normalized by contractile protein content was 23% less for OVX than OVX + E2 mice (Fig. 4A, right; Table 3), substantiating the hypothesis that E2 status affects force generation independent of muscle activity. There was a main effect of innervation status on absolute Po of soleus muscle, which is explained by the low contractile protein content because there was no effect of denervation on normalized Po (Table 3). Active stiffness, indicative of strong binding of myosin to actin, was also 21% lower in OVX than OVX + E2 mice, irrespective of innervation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of denervation on composition and in vitro contractile properties of soleus muscle from OVX + E2 and OVX mice

| Control Limb |

Denervated Limb |

P Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVX + E2 | OVX | OVX + E2 | OVX | Estradiol effect | Denervation effect | Interaction | |

| Muscle mass, mg | 8.8 (0.8) | 9.1 (0.8) | 5.7 (0.8) | 5.5 (0.6) | 0.955 | <0.001 | 0.298 |

| Muscle length, mm | 11.0 (0.6) | 10.9 (0.5) | 10.0 (0.5) | 9.9 (0.5) | 0.636 | <0.001 | 0.831 |

| Total protein, mg | 1.024 (0.23) | 0.907 (0.08) | 0.596 (0.13) | 0.570 (0.08) | 0.173 | <0.001 | 0.282 |

| Contractile protein, mg | 0.76 (0.15) | 0.73 (0.13) | 0.42 (0.12) | 0.42 (0.08) | 0.661 | <0.001 | 0.767 |

| Po, m · N | 144.0 (23.1) | 126.8 (24.9) | 102.0 (25.5) | 68.7 (24.5) | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.363 |

| Normalized Po, N · cm · mg−1 | 0.158 (0.03) | 0.140 (0.05) | 0.175 (0.04) | 0.115 (0.03) | 0.002 | 0.682 | 0.165 |

| Active stiffness, N/m | 334.5 (40.5) | 283.6 (37.9) | 270.6 (43.4) | 213.6 (62.2) | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.590 |

| Vmax, fl/s | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.6 (1.0) | 0.578 | 0.659 | 0.597 |

| Maximal power, mW | 0.36 (0.05) | 0.35 (0.06) | 0.26 (0.06) | 0.18 (0.06) | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.165 |

| Normalized power, mW/mg | 0.50 (0.07) | 0.48 (0.15) | 0.70 (0.20)* | 0.41 (0.14)† | 0.048 | ||

Values are means (SD); n = 10 in each group. OVX + E2 and OVX mice were subjected to left tibial nerve transection (Denervated Limb); the right limb remained intact and served as the intra-animal control (Control Limb). Po, maximal isometric tetanic force; Vmax, maximal shortening velocity; fl, fiber length. Po and power were normalized by contractile protein content. Data within each study were analyzed by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA (E2 × intervention, with intervention being the repeated factor):

significantly different from Control + E2;

significantly different from Denervated + E2.

Fig. 4.

Contractility of soleus muscles from ovariectomized mice following 2 wk of 17β-estradiol (OVX + E2) or placebo (OVX) treatment combined with unilateral soleus muscle denervation. Data [means (SD), n = 10 per group] are shown relative to control, nerve-intact limb of OVX + E2 mice. Normalized Po and power are Po and power adjusted by the ratio of contractile protein content to fiber length. Data were analyzed by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA (treatment × limb). Main effects of estradiol or denervation are shown above bars. Interaction post hoc results are as follows: *significantly different from Control + E2; †significantly different from Denervated + E2.

Vmax and maximal power of soleus muscles were also investigated as additional contractility parameters potentially affected by E2 status. There was no effect of E2 or denervation on soleus muscle Vmax, with the average for all muscles equaling 4.5 fiber lengths/s (SD 0.8) (Table 3). Nevertheless, there were main effects of E2 and denervation on maximal power (Fig. 4B, left; Table 3). Innervated soleus muscles generated ∼33% more power than denervated soleus muscles, and soleus muscles from OVX + E2 mice generated ∼25% more power than soleus muscles from OVX mice. When maximal power was normalized to contractile protein content, an interaction between E2 status and innervation was detected (Fig. 4B, left; Table 3). These in vitro parameters of soleus muscle indicate that, with the exception of normalized power, E2 has positive effects on muscle contractility that are independent of skeletal muscle activity.

DISCUSSION

We know that skeletal muscle function is detrimentally and beneficially affected by low and high levels of physical activity, respectively, and that E2 status influences physical activity, specifically wheel running, in rodents. This suggests that effects of E2 on skeletal muscle could result indirectly from altered physical activity levels. The effects of E2 on muscle in which we are most interested are the decrements in force generation and myosin function that occur as a result of E2 deficiency (17, 21, 22, 35). To help elucidate if those functional decrements are due directly to ovariectomy-induced E2 deficiency or if declines in the mouse's physical activity contribute to the decrements, in study I, we investigated the influence of ovariectomy on cage activities of mice. The chief finding was that OVX mice were less active in their standard mouse cages than OVX + E2 mice. This equated to the E2-deficient mice spending 1 h less time being physically active every day, which theoretically, over 30–60 days, could detrimentally impact the contractile function of those lesser-recruited muscles.

Our finding that cage activities were reduced in ovariectomized mice is consistent with previous observations in female rodents. The most commonly used measure of rodent physical activity has been wheel running, with distance run by E2-deficient females being only 20–40% of distance run by E2-replete females (7, 14, 24, 26, 36). Acute monitoring of ovariectomized and ovary-intact mice has also shown effects of E2 on physical activity behaviors associated with fear and arousal (24, 26). Finally, previous studies in mice and rats showed that ambulatory activity is reduced in ovarian hormone-deficient females, particularly during the dark phase (12, 28, 31). The decreases in 24-h cage activity we measured by active time, distance traveled, and rearing, jumping, and stereotypic counts were 20–55% less in ovariectomized mice, broadening our knowledge of systemic treatment effects of E2 on rodents. We concluded that the effects of E2 on physical activity need to be considered as a potentially confounding factor in efforts to determine the mechanism(s) of E2's effects on skeletal muscle and myosin functions. Thus, in studies II and III, we examined the direct influence of E2 by attempting to equalize physical and muscle activities of mice with low and normal levels of E2 by hindlimb suspension and tibial nerve transection. Our hypothesis was that E2-mediated effects on skeletal muscle are independent of physical activity. This hypothesis was supported by our main findings from studies II and III.

The first main result supporting our hypothesis was that when the degree of load bearing by the mouse's hindlimbs was clamped at a low level by hindlimb suspension, significant effects of ovarian hormones on the capacity of soleus muscle to generate force remained. In particular, normalized Po was ∼30% lower in soleus muscles from ovariectomized than ovary-intact mice. These findings were further substantiated when soleus muscle activity was controlled by tibial nerve transection. The second major result was that soleus muscles from OVX mice generated 20–25% less absolute and normalized force than those from OVX + E2 mice, regardless of innervation state. The results of the hindlimb suspension study implicated ovarian hormones, whereas data from the denervation study directly showed that E2 is the key ovarian hormone affecting contractility because treatment with E2 reversed the detrimental contractile effects of ovariectomy. Overall, our hypothesis that the effects of E2 on soleus muscle function are independent of physical and muscle activity was supported.

While hormone manipulation for 2 wk was sufficient to cause functional changes in soleus muscle, significant changes in the ability of EDL muscle to generate force were not elicited. Two previous studies showed that relatively short durations of E2 manipulation, i.e., 2.5–3 wk, were sufficient to affect dorsiflexor muscle function in mice (29, 35), and we previously showed that ovarian hormone manipulation for 30 or 60 days affects contractility of EDL and soleus muscles similarly (21). We can only surmise that soleus muscle is slightly quicker to respond to E2 manipulation than is EDL muscle, although the reason for this is not known.

Beyond E2's influence on force generation, there are indications that it may affect muscle fatigue and power. Results of studies of E2's effect on muscle fatigue are conflicting: one study indicates a beneficial effect (11), one study indicates a negative effect in situ and no effect in vitro (39), and a third study indicates no effect (33). Tiidus and colleagues (29) went on to suggest that progesterone, not E2, may improve fatigue resistance. In study II, we found no effect of ovarian hormones on the fatigability of isolated soleus muscle. Muscle power was also investigated because E2 has been shown to influence parameters related to velocity of contraction. We previously showed that soleus muscle Vmax increased by ∼10% following the loss of ovarian hormones for 60 days (22). In addition, others have determined faster muscle twitch parameters of ovariectomized rats (18). In study III, Vmax was not affected by E2, but maximal power was affected: it was ∼30% lower in soleus muscles from OVX than OVX + E2 mice. This effect of E2 on power was due to E2's impact on force generation, not velocity, and again was elicited irrespective of chronic muscle activity.

One mechanism underlying E2's influence on skeletal muscle force generation is its effect on myosin function, and we hypothesize that this mechanism is the result of chronic exposure of E2 on skeletal muscle (17). This hypothesis is based on our previous work showing that the fraction of myosin in its strong-binding, force-generating structural state during contraction is greater in skeletal muscle from sham-operated or ovariectomized, E2-replaced than untreated, ovariectomized mice (22). This has been measured directly in fibers by site-specific spin labeling of myosin combined with electron paramagnetic resonance. In those studies, the same result was obtained by analysis of muscle's active stiffness, which is an indirect measure of the degree of actin strongly bound to myosin during contraction (16). In studies II and III, active stiffness was 15% lower in soleus muscles from OVX than Sham or OVX + E2 mice, with this being statistically significant in study III. These data suggest a positive effect of E2 on myosin's function to generate force at the molecular level. This result, combined with E2's beneficial effect on normalized force generation, indicates an E2 effect on skeletal muscle quality, as opposed to some effect on muscle growth or size (17).

In summary, by minimizing the effects of physical and muscle activity on muscle function, the results of the present work clearly show that the effects of E2 are directly on the muscle and are not an indirect result of E2 changing the behavior and, thus, physical and muscular activities of the mice. On the basis of this work and our previous work, we believe that E2 affects the intrinsic ability of skeletal muscle to generate force (17). Future studies to determine the underlying mechanisms by which E2 influences skeletal muscle and myosin functions are warranted.

GRANTS

The research was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R01-AG-031743 (to D. A. Lowe). A. L. Moran and K. A. Baltgalvis were supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Training Grant T32-AR-07612.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bar PR, Amelink GJ, Oldenburg B, Blankenstein MA. Prevention of exercise-induced muscle membrane damage by oestradiol. Life Sci 42: 2677–2681, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis (Statistics in Practice). New York: Wiley, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Contractile properties of skeletal muscles from young, adult and aged mice. J Physiol 404: 71–82, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Claflin DR, Faulkner JA. The force-velocity relationship at high shortening velocities in the soleus muscle of the rat. J Physiol 411: 627–637, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gordon T, Stein RB. Comparison of force and stiffness in normal and dystrophic mouse muscles. Muscle Nerve 11: 819–827, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gorzek JF, Hendrickson KC, Forstner JP, Rixen JL, Moran AL, Lowe DA. Estradiol and tamoxifen reverse ovariectomy-induced physical inactivity in mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 248–256, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greising SM, Baltgalvis KA, Lowe DA, Warren GL. Hormone therapy and skeletal muscle strength: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64: 1071–1081, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayes A, Williams DA. Beneficial effects of voluntary wheel running on the properties of dystrophic mouse muscle. J Appl Physiol 80: 670–679, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hicks AL, Kent-Braun J, Ditor DS. Sex differences in human skeletal muscle fatigue. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 29: 109–112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hou YX, Jia SS, Liu YH. 17β-Estradiol accentuates contractility of rat genioglossal muscle via regulation of estrogen receptor-α. Arch Oral Biol 55: 309–317, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Isken F, Pfeiffer AF, Nogueiras R, Osterhoff MA, Ristow M, Thorens B, Tschop MH, Weickert MO. Deficiency of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor prevents ovariectomy-induced obesity in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E350–E355, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Josephson RK. Contraction dynamics and power output of skeletal muscle. Annu Rev Physiol 55: 527–546, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kadi F, Karlsson C, Larsson B, Eriksson J, Larval M, Billig H, Jonsdottir IH. The effects of physical activity and estrogen treatment on rat fast and slow skeletal muscles following ovariectomy. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 23: 335–339, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landisch RM, Kosir AM, Nelson SA, Baltgalvis KA, Lowe DA. Adaptive and nonadaptive responses to voluntary wheel running by mdx mice. Muscle Nerve 38: 1290–1303, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linari M, Dobbie I, Reconditi M, Koubassova N, Irving M, Piazzesi G, Lombardi V. The stiffness of skeletal muscle in isometric contraction and rigor: the fraction of myosin heads bound to actin. Biophys J 74: 2459–2473, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lowe DA, Baltgalvis KA, Greising SM. Mechanisms behind estrogen's beneficial effect on muscle strength in females. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 38: 61–67, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCormick KM, Burns KL, Piccone CM, Gosselin LE, Brazeau GA. Effects of ovariectomy and estrogen on skeletal muscle function in growing rats. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 25: 21–27, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCully KK, Faulkner JA. Characteristics of lengthening contractions associated with injury to skeletal muscle fibers. J Appl Physiol 61: 293–299, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Modder UI, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC, Fraser DG, Atkinson EJ, Arnold R, Khosla S. Dose-response of estrogen on bone versus the uterus in ovariectomized mice. Eur J Endocrinol 151: 503–510, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moran AL, Nelson SA, Landisch RM, Warren GL, Lowe DA. Estradiol replacement reverses ovariectomy-induced muscle contractile and myosin dysfunction in mature female mice. J Appl Physiol 102: 1387–1393, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moran AL, Warren GL, Lowe DA. Removal of ovarian hormones from mature mice detrimentally affects muscle contractile function and myosin structural distribution. J Appl Physiol 100: 548–559, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moran AL, Warren GL, Lowe DA. Soleus and EDL muscle contractility across the lifespan of female C57BL/6 mice. Exp Gerontol 40: 966–975, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morgan MA, Pfaff DW. Effects of estrogen on activity and fear-related behaviors in mice. Horm Behav 40: 472–482, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nelson JF, Felicio LS, Randall PK, Sims C, Finch CE. A longitudinal study of estrous cyclicity in aging C57BL/6J mice. I. Cycle frequency, length and vaginal cytology. Biol Reprod 27: 327–339, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogawa S, Chan J, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Estrogen increases locomotor activity in mice through estrogen receptor-α: specificity for the type of activity. Endocrinology 144: 230–239, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Persky AM, Green PS, Stubley L, Howell CO, Zaulyanov L, Brazeau GA, Simpkins JW. Protective effect of estrogens against oxidative damage to heart and skeletal muscle in vivo and in vitro. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 223: 59–66, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rogers NH, Perfield JW, 2nd, Strissel KJ, Obin MS, Greenberg AS. Reduced energy expenditure and increased inflammation are early events in the development of ovariectomy-induced obesity. Endocrinology 150: 2161–2168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schneider BS, Fine JP, Nadolski T, Tiidus PM. The effects of estradiol and progesterone on plantarflexor muscle fatigue in ovariectomized mice. Biol Res Nurs 5: 265–275, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schoenberg M, Wells JB. Stiffness, force, and sarcomere shortening during a twitch in frog semitendinosus muscle bundles. Biophys J 45: 389–397, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimomura Y, Shimizu H, Takahashi M, Sato N, Uehara Y, Fukatsu A, Negishi M, Kobayashi I, Kobayashi S. The significance of decreased ambulatory activity during the generation by long-term observation of obesity in ovariectomized rats. Physiol Behav 47: 155–159, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tiidus PM. Can estrogens diminish exercise induced muscle damage? Can J Appl Physiol 20: 26–38, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tiidus PM, Bestic NM, Tupling R. Estrogen and gender do not affect fatigue resistance of extensor digitorum longus muscle in rats. Physiol Res 48: 209–213, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Warren GL, Hayes DA, Lowe DA, Williams JH, Armstrong RB. Eccentric contraction-induced injury in normal and hindlimb-suspended mouse soleus and EDL muscles. J Appl Physiol 77: 1421–1430, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Warren GL, Lowe DA, Inman CL, Orr OM, Hogan HA, Bloomfield SA, Armstrong RB. Estradiol effect on anterior crural muscles-tibial bone relationship and susceptibility to injury. J Appl Physiol 80: 1660–1665, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Warren GL, Moran AL, Hogan HA, Lin AS, Guldberg RE, Lowe DA. Voluntary run training but not estradiol deficiency alters the tibial bone-soleus muscle functional relationship in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R2015–R2026, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wattanapermpool J, Reiser PJ. Differential effects of ovariectomy on calcium activation of cardiac and soleus myofilaments. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H467–H473, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wattanapermpool J, Riabroy T, Preawnim S. Estrogen supplement prevents the calcium hypersensitivity of cardiac myofilaments in ovariectomized rats. Life Sci 66: 533–543, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wohlers LM, Sweeney SM, Ward CW, Lovering RM, Spangenburg EE. Changes in contraction-induced phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinases in skeletal muscle after ovariectomy. J Cell Biochem 107: 171–178, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]