Abstract

Presenilins were first discovered as sites of missense mutations responsible for early-onset Alzheimer disease (AD). The encoded multipass membrane proteins were subsequently found to be the catalytic components of γ-secretases, membrane-embedded aspartyl protease complexes responsible for generating the carboxyl terminus of the amyloid β-protein (Aβ) from the amyloid protein precursor (APP). The protease complex also cleaves a variety of other type I integral membrane proteins, most notably the Notch receptor, signaling from which is involved in many cell differentiation events. Although γ-secretase is a top target for developing disease-modifying AD therapeutics, interference with Notch signaling should be avoided. Compounds that alter Aβ production by γ-secretase without affecting Notch proteolysis and signaling have been identified and are currently at various stages in the drug development pipeline.

γ-Secretases produce amyloid β-protein in Alzheimer disease, but they also regulate Notch signaling. Drugs that alter amyloid β-protein production without affecting Notch signaling are currently under development.

As described in Haas et al. (2011), the amyloid protein precursor (APP) undergoes successive proteolysis by β- and γ-secretases to produce the amyloid β-protein (Aβ) that characteristically deposits in the brain in Alzheimer disease (AD). Both of these proteases are top targets for AD drug discovery, although each presents challenges for developing safe and effective therapeutics. γ-Secretase is a large complex of four different integral membrane proteins, with presenilin as the catalytic component comprising an unusual membrane-embedded aspartyl protease. Herein, we describe the discovery of the γ-secretase components, the biological functions of γ-secretase, as well as other roles of presenilin outside the protease complex, what is known so far about the structure of the complex, the role of γ-secretase in disease (especially in AD), and the current status and direction of γ-secretase inhibitors and modulators as candidate AD therapeutics.

THE IDENTIFICATION OF THE PRESENILINS AND THE OTHER γ-SECRETASE SUBUNITS

The name “γ-secretase” was used for the first time in 1993 to describe the proteolytic activity that cleaves APP in the transmembrane domain (TMD) (Haass and Selkoe 1993). It took about 10 years to identify all of the components of the molecular machine responsible for this cleavage (De Strooper 2003). The first step forward was in 1995 when two lines of genetic investigation merged unexpectedly into the identification of the presenilins. Analysis of families with inherited forms of AD were found to contain mutations in the until then unknown genes presenilin 1 (PSEN1; see Fig. 1 for protein sequence, topology, and sites of mutations) on chromosome 14q24.3 (Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Group 1995; Sherrington et al. 1995) and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) on chromosome 1q42.2 (Levy-Lahad et al. 1995; Rogaev et al. 1995). A second line of genetic investigation, in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, independently identified a presenilin gene as a suppressor of lin-12 gain-of-function mutants (Levitan and Greenwald 1995). lin-12 is the worm ortholog of Notch, a gene critical for cell signaling during development. Thus, presenilin was important in the pathogenesis of AD and at the same time for development by regulating Notch signaling. However, the link between these two functions remained unclear, and it was proposed that presenilins could act as a channel, a receptor, or a transporter protein or even affect tau phosphorylation and dysfunction.

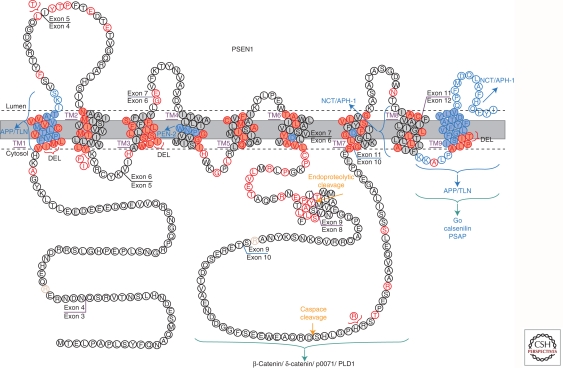

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence, topology, and mutations in presenilin 1. Single amino acid residues that have been found to be substituted by mutations causing familial AD are indicated in red. Exon/intron boundaries, the different transmembrane domains (TM1-TM9), residues (blue) involved in the interaction with amyloid precursor protein (APP), telencephalin (TLN), PEN-2, Nicastrin (NCT), and APH-1 are indicated with brackets. (This figure was adapted from Dillen and Annaert 2006; reprinted, with permission, from Elsevier ©2006. It is based on a figure published on the Alzforum website http://www.alzforum.org/res/com/mut/pre/diagram1.asp.)

The first clue to the role of presenilins in APP processing came from observations that AD-causing mutations in PSEN1 and PSEN2 (more than 150 different mutations in these genes have been identified) affect the generation of Aβ peptides, changing the relative amount of Aβ42 peptide (Aβ containing 42 amino acid residues) versus the shorter Aβ40 (the more abundantly generated peptide, containing 40 amino acid residues; see Haas et al. 2011). This was shown in fibroblasts derived from patients (Scheuner et al. 1996), by overexpressing the mutant presenilins in cell lines (Borchelt et al. 1996; Citron et al. 1997), and by experiments in living mice, either overexpressing the mutant presenilin in brain using various promoters (Borchelt et al. 1996, 1997; Duff et al. 1996; Citron et al. 1997) or by knocking in mutations in the endogenous mouse presenilin gene (Siman et al. 2000; Flood et al. 2002).

The function of presenilin in the γ-secretase proteolytic activity became apparent when neurons were derived from PSEN1 knockout mice and used to show that PSEN1 was critically involved in the generation of all Aβ peptides (De Strooper et al. 1998). This experiment established presenilin as an important AD drug target (Haass and Selkoe 1998). The central role of presenilin in the γ-secretase processing of Notch was established a year later in mouse and Drosophila (De Strooper et al. 1999; Struhl and Greenwald 1999). Furthermore, because a γ-secretase inhibitor was shown to block not only APP processing but also Notch cleavage (De Strooper et al. 1999), it was suggested that a presenilin-dependent protease was responsible for both cleavages, and that blocking this enzyme would cause major side effects in patients. Notch is indeed not only involved in embryogenesis and development but also in differentiation of immune cells, the goblet cells in the intestine, and others (van Es et al. 2005).

At the same time, other studies suggested that presenilin was actually the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase. Site-directed mutagenesis of two aspartyl residues embedded in the TMDs VI and VII of PSEN1 resulted in a dominant-negative effect on γ-secretase activity, suggesting that presenilin was a protease, specifically of the aspartyl type (Wolfe et al. 1999b). These mutations did not affect the expression or the incorporation of presenilin into the γ-secretase complex (Nyabi et al. 2003), and are in a conserved region of the presenilin proteins (Steiner et al. 2000). They are found in a family of related intramembrane-cleaving proteases, the signal peptide peptidases (SPP) (Ponting et al. 2002; Weihofen et al. 2002). Finally, transition-state analog (i.e., active site-directed) γ-secretase inhibitors were shown to directly bind to the presenilin subunit of the γ-secretase complex (Esler et al. 2000; Li, Xu et al. 2000), providing convincing evidence that presenilin is indeed a protease.

In mammals, two homologous proteins exist, i.e., PSEN1 and PSEN2. They are both synthesized as precursor proteins of 50 kDa with nine TMDs (Laudon et al. 2005; Spasic et al. 2006), and are cleaved into a 30 kDa amino-terminal fragment (NTF) and a 20 kDa carboxy-terminal fragment (CTF) during maturation (Thinakaran et al. 1996), probably by autocatalysis (Wolfe et al. 1999b,c; Fukumori et al. 2010).

Together with other proteases, presenilins represent a novel class of intramembrane-cleaving proteases or i-clips (Wolfe et al. 1999c; Wolfe and Kopan 2004). However, the presenilins are different from other i-clips, in the sense that they need three other protein subunits to achieve optimal activity. Early reports already suggested that it is not possible to overexpress presenilin in a functionally active way, as additional proteins (“limiting factors”) are needed for presenilin to mature into stable NTF plus CTF heterodimers (Baumann et al. 1997; Thinakaran et al. 1997). The first “limiting” factor was coisolated in an immunochemical purification protocol using antibodies against presenilin. The resultant 130 kDa type I integral membrane protein was baptized Nicastrin (Yu et al. 2000). The genes for Nicastrin and for the two other proteins of the γ-secretase complex were also identified independently in screens for modifiers of Notch homologs glp-1 and lin-12 in C. elegans. Aph-1 (for “anterior pharynx-defective phenotype”) is a 30 kDa protein with 7 TMDs (Goutte et al. 2000; Levitan et al. 2001; Goutte et al. 2002), and Pen-2 (for “presenilin enhancer”) is a 12 kDa hairpinlike, two-transmembrane protein (Francis et al. 2002). A series of reconstitution and knockdown experiments established that the four proteins (Fig. 2) are necessary and sufficient for γ-secretase processing (Edbauer et al. 2003; Kimberly et al. 2003; Takasugi et al. 2003). Both genetic screens (Francis et al. 2002) and recent purifications of the γ-secretase complex (Teranishi et al. 2009; Wakabayashi et al. 2009; Winkler et al. 2009) were not able to identify additional proteins stably associated with the complex, suggesting strongly that the core of the complex has been identified. Additional proteins might, however, be involved in the regulation of the activity or subcellular localization of the complex (Chen et al. 2006; Wakabayashi et al. 2009; He et al. 2010).

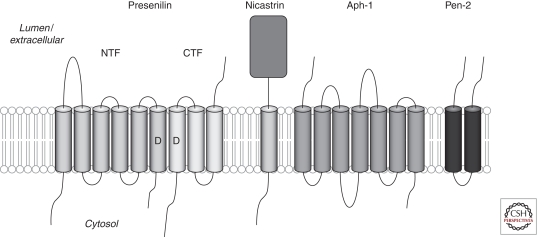

Figure 2.

Subunits of the γ-secretase complex and their membrane topologies. Presenilin is proteolytically processed into two fragments during maturation of the complex, an amino-terminal fragment (NTF) and a carboxy-terminal fragment (CTF). The two transmembrane catalytic aspartic acid residues, one in the NTF and one in the CTF, are indicated by D. Other subunits are Nicastrin, APH-1, and PEN-2.

The stoichiometry of the γ-secretase complex is likely 1:1:1:1, based on molecular mass estimates in blue native electrophoresis (Kimberly et al. 2003), quantitative western blot analysis (Sato et al. 2007), and electron microscopy (EM) studies of the purified complex (Osenkowski et al. 2009). Thus, as there are two different PSEN genes and two different Aph1 genes (Aph1a and Aph1b) encoded in the human genome, it follows that at least four different γ-secretase complexes exist (De Strooper 2003). The situation is actually even more complicated, as alternatively spliced forms for the presenilins and for Aph-1a have been reported (Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Group 1995; Gu et al. 2003). The biological significance of this heterogeneity is only now being explored.

THE BIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF PRESENILIN

As discussed, the main function of the presenilins is to provide the catalytic subunits to the different γ-secretases (De Strooper et al. 1998, 1999; Wolfe et al. 1999b; Esler et al. 2000; Li et al. 2000). Over the years, other presenilin functions have been proposed—in protein trafficking and turnover, in calcium homeostasis, in regulation of β-catenin signaling, and others—sometimes within and sometimes outside of the γ-secretase complex. These putatively “nonproteolytic” functions can be shown using presenilins in which the catalytic aspartyl residues (Wolfe et al. 1999b) are replaced by other amino acid residues and showing that a particular function is not dependent on these aspartyl residues. This criterion has been met in several instances, e.g., for the calcium leak function of presenilin in the endoplasmic reticulum (Tu et al. 2006; Nelson et al. 2007), for the growth alterations caused by deficiencies in cytoskeleton function in a presenilin-deficient variant of the moss Physcomitrella patens (Khandelwal et al. 2007), or in the turnover of the membrane protein telencephalin (Esselens et al. 2004).

To focus first on the proteolytic functions of γ-secretase (Fig. 3), the crucial and conserved role of presenilin in Notch signaling (Levitan and Greenwald 1995; De Strooper et al. 1999; Struhl and Greenwald 1999) has been repeatedly shown. In all species, severe developmental defects are associated with altered expression of Notch target genes such as the “hairy and enhancer of split” (HES) family. By using conditionally targeted alleles or partial knockouts of presenilin or else γ-secretase inhibitors, it is possible to evaluate the role of presenilin in Notch signaling in adulthood. Deficiencies in T- and B-cell differentiation (Doerfler et al. 2001; Hadland et al. 2001; Qyang et al. 2004; Tournoy et al. 2004; Wong et al. 2004), bloody diarrhea as a consequence of hampered intestinal goblet cell differentiation (Searfoss et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2004; van Es et al. 2005), and skin and hair defects (Xia et al. 2001; Tournoy et al. 2004), have been observed. Conditional knockout of presenilins in the forebrain (using an αCaMKII promoter to drive Cre expression) leads to progressive neurodegeneration, which has been proposed as an argument that loss of presenilin function could contribute to the pathogenesis of sporadic AD independently of affecting Aβ42 generation (discussed in Shen and Kelleher 2007). However, the predictable absence of Aβ deposition in these knockout mice means that they do not constitute a model of AD.

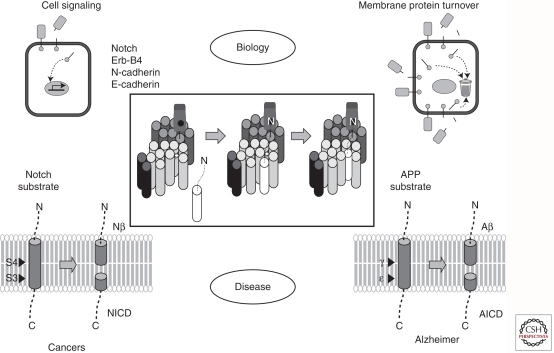

Figure 3.

The role of the γ-secretase complex in biology and disease. Proteolytic processing of certain substrates (e.g., Notch, ErbB4, N-cadherin, E-cadherin) leads to cell signaling. Alternatively, processing of substrates by γ-secretase is simply a means of clearing protein stubs from the membrane. Excessive signaling from the Notch receptor leads to certain forms of cancer, and formation of the amyloid β-protein from its precursor APP by γ-secretase is involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease.

It is clear that Notch phenotypes are predominant in presenilin-deficient animals, and interference with the Notch signaling pathway is the greatest concern when developing γ-secretase inhibitors to treat AD patients. However, over the years, more than 60 other proteins have been proposed as substrates for the γ-secretases (for an overview, see Hemming et al. 2008, Wakabayashi and De Strooper 2008, and McCarthy et al. 2009). Interestingly, the phenotypes of the mice in which individual subunits of γ-secretase (i.e., PSEN1 or PSEN2 and Aph1a or Aph1b/c) have been knocked out are quite divergent, suggesting some specificity in the substrates cleaved by the different γ-secretase complexes in vivo. The Aph1b/c containing γ-secretase complexes can, for instance, be completely removed from the mouse genome without causing any Notch defects, whereas similar inactivation of the Aph1a-complexes leads to severe embryonic phenotypes (Ma et al. 2005; Serneels et al. 2005, 2009). Interestingly, Aph1b/c knockout mice display subtle behavioral phenotypes characterized by disturbed prepulse inhibition, increased amphetamine sensitivity, and alterations in an operational memory task (Dejaegere et al. 2008). Accumulation of neuregulin CTFs in brain extracts of these mice suggested that neuregulin is a substrate of Aph1b/c-γ-secretase. Similar phenotypes have been seen in neuregulin-deficient mice (Stefansson et al. 2002) and interestingly, also in BACE-1 knockout mice (Savonenko et al. 2008), in agreement with the fact that BACE-1 is the principal sheddase of neuregulin (Willem et al. 2006).

The biochemical evidence that the APP and its close relatives, amyloid precursor-like protein (APLP)-1 and -2 are substrates of γ-secretase in vivo is also beyond discussion (De Strooper et al. 1998; Naruse et al. 1998; Scheinfeld et al. 2002; Eggert et al. 2004; Yanagida et al. 2009). As described in Müller and Zheng (2011), APP-deficient animals have yielded little direct information with regard to the specific molecular pathways for which APP is required, and it therefore remains unclear to what extent γ-secretase processing of APP (apart from generating the infamous Aβ peptide) has biological consequences. γ-Secretase inactivation causes accumulation of APP carboxy-terminal fragments (APP-CTF) to levels which are two- to threefold higher than what is observed in wild-type cells, and Aβ peptide is no longer produced. It is possible that the main role of γ-secretase processing of the APP membrane-bound fragments is to clear these hydrophobic remnants (Kopan and Ilagan 2004), although some evidence suggests that the released APP intracellular domain might be involved in signaling processes (critically discussed in Reinhard et al. 2005). Importantly, also in the context of the development of γ-secretase inhibitors for the clinic, it seems that additional clearance mechanisms can compensate for the loss of γ-secretase processing by removing APP CTFs via alternative pathways. Other substrates that have been well studied are the N- and E-cadherins. Presenilin-1 forms complexes with these proteins and the α- and β-catenins at the cell surface (Georgakopoulos et al. 1999). γ-Secretase proteolysis of E-cadherin results in the release of the associated β- (and α-) catenins and disassembly of the adherens junction (Marambaud et al. 2002). N-cadherin cleavage by γ-secretase is stimulated by NMDA agonists. The cleavage gives rise to an intracellular N-cadherin fragment that binds to CBP (the cyclic AMP response element binding protein [CREB] binding protein) (Marambaud et al. 2003).

Presenilins have also been implicated in the cellular trafficking of proteins. Given the many substrates of presenilin, it is not unexpected that interference with proteolysis will lead to abnormal accumulation of protein fragments in the cell. However, a number of cell-surface proteins that are apparently not substrates of γ-secretase, including intercellular adhesion molecule 5 (ICAM5) or telencephalin (Esselens et al. 2004), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Repetto et al. 2007), and β1-integrins (Zou et al. 2008), are also mislocalized in presenilin-deficient cells. Defective transport between endosomes and lysosomes or other deficits in late endosomal or other degradative organelles have been proposed to explain the abnormal accumulation of these proteins in presenilin knockout cells (Esselens et al. 2004; Wilson et al. 2004; Repetto et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2010).

The role of presenilin in Ca2+ homeostasis is even more controversial. There is consensus that clinical mutations in presenilin disturb the Ca2+ pool at the level of the ER (Bezprozvanny and Mattson 2008). The mechanisms, however, are debated and include higher expression of the Ryanodine receptor (RyR) (Chan et al. 2000; Hayrapetyan et al. 2008), stimulation of inositol-3-phosphate (IP3)-induced ER Ca2+ release (Leissring et al. 1999; Kasri et al. 2006; Cheung et al. 2008), or stimulation of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pumps (Green et al. 2008). Presenilins might act as Ca2+ leak channels themselves (Tu et al. 2006). This leakage function is only observed with full-length presenilin-1 (i.e., before it becomes incorporated into the γ-secretase complex), and again, presenilin-containing aspartate mutations are able to maintain this function.

STRUCTURE-FUNCTION RELATIONSHIP OF γ-SECRETASE

The first step in understanding the structure of a membrane protein complex such as γ-secretase is to determine the membrane topology of the individual components. Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and PSEN2 are integral membrane proteins that span membranes multiple times: Initially, the amino and carboxyl termini of PSEN1 and PSEN2 were predicted to be oriented to the cytoplasmic side (Doan et al. 1996), but a later N-linked glycosylation scanning approach revealed that PSEN spans the membrane nine times, with amino and carboxyl termini being oriented to the cytoplasmic and luminal sides, respectively (Laudon et al. 2005). Nicastrin is a type I single-span membrane protein with a large extracellular domain, the latter being heavily glycosylated and tightly folded on maturation (Shirotani et al. 2003). Aph-1 is apparently a 7-TMD protein with its amino and carboxyl termini located on the luminal and cytoplasmic sides, respectively (Fortna et al. 2004). Pen-2 spans the membrane twice, with both the amino and carboxyl termini being found on the luminal side (Crystal et al. 2003).

Another fundamental issue toward elucidating the structure of the γ-secretase complex is determining its protein–protein contacts. Which components are bound to each other, and what are the binding domains? Nicastrin and Aph-1 form an initial subcomplex in the endoplasmic reticulum (LaVoie et al. 2003), and multiple TMDs of Aph-1 are involved in the binding to Nicastrin (Pardossi-Piquard et al. 2009; Chiang et al. 2010). The Nicastrin/Aph-1 subcomplex then interacts with the PSEN and Pen-2 subcomplex (Fraering et al. 2004a). Site-directed mutagenesis combined with coimmunoprecipitation studies showed that the carboxy-terminal domain of PSEN interacts with the TMD of Nicastrin (Capell et al. 2003; Kaether et al. 2004). Aph-1 also directly interacts with the carboxy-terminal region of PSEN (Steiner et al. 2008). Binding of Pen-2 to PSEN occurs independently of the Nct/Aph-1 interaction (Fraering et al. 2004a). It has also been shown that PSEN1 interacts with Pen-2 through its fourth TMD (Kim and Sisodia 2005; Watanabe et al. 2005).

Because of the unique features of γ-secretase as a membrane-embedded protein complex harboring at least 19 membrane-spanning regions and executing intramembrane hydrolysis of substrate proteins, there is great interest in its precise structure. However, crystallization of the purified γ-secretase complex has not been achieved yet. Hence, a couple of indirect approaches have been conducted to begin to predict the structure of the complex. EM and single-particle image analysis on human γ-secretase complexes purified from mammalian cells revealed a cylindrical interior chamber of ∼20–40 Å length, consistent with a proteolytic site occluded from the hydrophobic environment of the lipid bilayer. Lectin tagging of the Nicastrin ectodomain enabled proper orientation of the globular, ∼120 Å-long complex within the membrane (Lazarov et al. 2006). Further analysis of the structure of γ-secretase complex by cryoelectron microscopy and single-particle image reconstruction at 12 Å resolution revealed several domains on the extracellular side, three low-density cavities, and a surface groove in the transmembrane region of the complex (Osenkowski et al. 2009). Human γ-secretase complexes reconstituted in Sf9 cells have also been purified and analyzed by EM and 3D reconstruction (Ogura et al. 2006). The resultant three-dimensional structure of γ-secretase at 48 Å resolution occupied a volume of 560 × 320 × 240 Å, which resembled a flattened heart comprised of two oppositely faced, dimpled domains; a low-density space containing multiple pores resided between the domains, which may house the catalytic site. The differences in the predicted shape and size of the complex between the two studies may reflect monomeric versus dimeric or oligomeric states and may stem from the distinct conditions for reconstitution, detergent extraction and purification, as well as the limitation of the resolution of the method for revealing the internal structure of γ-secretase at the atomic level.

The most intriguing aspect in the structure-function relationship of γ-secretase is how it executes the proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-spanning segment of substrate proteins within the hydrophobic lipid bilayer. To examine the water accessibility of the regions flanking the catalytic aspartate residues in the sixth and seventh TMDs of PSEN1, the substituted cysteine accessibility method (SCAM) was applied. This involves the use of disulfide-forming reagents to probe accessibility of specific amino acids that have been changed to cysteines. Via SCAM, TMD6 and TMD7 were found to be partly facing a hydrophilic environment (i.e., in a catalytic pore structure) that enables the intramembrane proteolysis (Fig. 4A) (Sato et al. 2006; Tolia et al. 2006). Residues at the luminal portion of TMD6 are predicted to form a subsite for substrate or inhibitor binding on the α-helix facing a hydrophilic milieu, whereas those around the GxGD catalytic motif within TMD7 are highly water accessible, suggesting formation of a hydrophilic cavity within the membrane region. The SCAM data also suggested that the two catalytic aspartates are closely opposed to each other. Subsequently, the structures of TMD 8, 9, and the carboxyl terminus of PSEN1, which are located carboxy terminally to the catalytic domain and include the conserved PAL motif and the hydrophobic carboxy-terminal tip, both of which are implicated in the formation of the γ-secretase complex and its catalytic activity, were analyzed by SCAM (Fig. 4B) (Sato et al. 2008; Tolia et al. 2008). The amino acid residues around the proline-alanine-leucine (PAL) motif and the luminal side of TMD9 were highly water accessible and located in proximity to the catalytic center. The region starting from the luminal end of TMD9 toward the carboxyl terminus formed an amphipathic α-helix-like structure that extended along the interface between the membrane and the extracellular milieu. Competition analysis using γ-secretase inhibitors showed the involvement of TMD9 in the initial binding of substrates, as well as in the subsequent catalytic process as a subsite. Recently, TMD1 of PS1 also was shown to be involved in the hydrophilic catalytic pore, serving as a part of subsite for γ-secretase cleavage, together with TMD 6, 7, and 9 (Takagi et al. 2010).

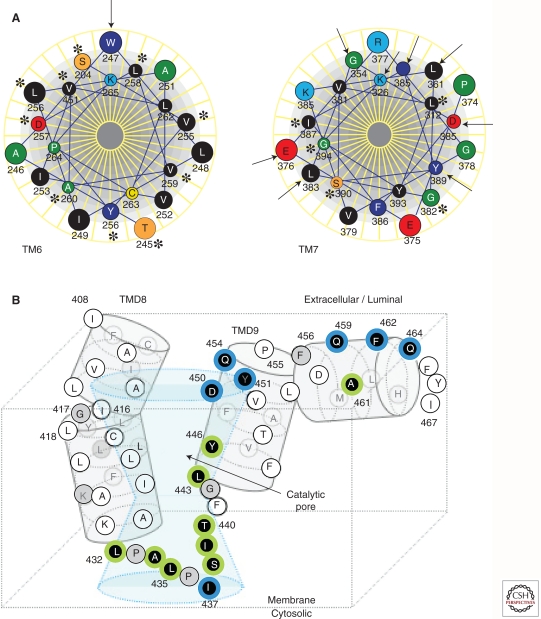

Figure 4.

Predicted structure in and around the putative catalytic pore of PS1 based on the results of SCAM analysis. (A) Helical wheel model of TMD6 and 7 viewed from the amino terminus. The arrows and asterisks indicate amino acids reactive and nonreactive to biotin-HPDP, respectively, by the SCAM analysis (Tolia et al. 2006). Note that most of the accessible residues cluster on one side, although this domain does not seem to be a classically amphipathic helix. (B) Hypothetical structure around TMD8, 9, and the extreme carboxyl terminus of PS1 in relation to the catalytic pore. Residues labeled by 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSEA)-biotin by the SCAM analysis (that are accessible to hydrophilic environment; Sato et al. 2008) are shown by a white letter in a black circle.

Recently, the structure of the CTF of human PS1 was analyzed by nuclear magnetic resonance studies in SDS micelles (Sobhanifar et al. 2010). The structure revealed a topology where the membrane was likely traversed three times in accordance with the nine TMD model of PS1, but containing unique structural features adapted to accommodate intramembrane catalysis, including a putative half-membrane-spanning helix amino-terminally harboring the second catalytic aspartate (residue 385), a severely kinked helical structure toward the carboxyl terminus, as well as a soluble helix in the unstructured amino-terminal loop of the CTF. These predicted structures were in good accordance with those obtained by SCAM analysis.

PRESENILINS AND DISEASE

As mentioned earlier, presenilin mutations were first identified in connection with familial AD, and subsequent work established that presenilin is the catalytic component of the γ-secretase complex that produces Aβ. This and other evidence strongly implicate Aβ, particularly Aβ42, in the pathogenesis of monogenic, dominant familial AD cases (i.e., those with missense mutations in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes). AD-associated mutations in the presenilins alter the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40, a critical factor in the tendency of Aβ to aggregate into neurotoxic species, whether the deleterious aggregates are fibrillar plaques or (according to current thinking) soluble oligomers (reviewed in Mucke 2011). Thus, these missense mutations alter the biochemical character of the γ-secretase complex and its interaction with the APP substrate to skew the transmembrane cleavage toward longer, more aggregation-prone forms of Aβ.

Interestingly, most of the AD-associated mutations in presenilin also cause a reduction in overall proteolytic activity (Song et al. 1999; Moehlmann et al. 2002; Schroeter et al. 2003; Bentahir et al. 2006), raising the question of whether a partial loss of presenilin function causes familial AD. Indeed, conditional knockout of PSEN1 and PSEN2 in the mouse brain results in neurodegeneration and memory deficits reminiscent of AD, albeit with no Aβ production (Saura et al. 2004; Wines-Samuelson et al. 2010). However, all of the mutations in the presenilins associated with AD (over 160 such mutations have been identified) are dominant, one mutant allele being sufficient to cause the carrier to develop AD in midlife. Furthermore, none of these AD-associated mutations result in truncation or loss of the presenilin protein, and the mutant protein assembles with other γ-secretase components into full complexes that are proteolytically active (and thus compatible with entirely normal development). Complete loss-of-function mutations in PSEN1, Pen-2, and Nicastrin in humans cause familial forms of a severe skin disorder, not neurodegeneration or AD (Wang et al. 2010). Although many of the AD-mutant forms of PSEN1 lead to some reduction in proteolytic function, some mutants display only subtle reductions, if any at all (Kulic et al. 2000). Moreover, no familial AD mutations have been found in any other γ-secretase substrate besides APP, strongly suggesting that it is alteration of APP proteolysis by the mutant presenilins that is the key to the pathogenesis of AD. Together, these observations suggest that an altered Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio is the critical factor by which presenilin mutations cause familial AD. Such mutations may or may not be accompanied by a reduction of proteolytic activity, but a complete loss of activity is not observed with any of these mutations. The phenotypes observed in the conditional knockout mice may reflect an essential role of presenilins in neuronal health or function (e.g., neurotransmitter release; Zhang et al. 2009) that is only revealed on complete removal of these proteins, and deficient Notch signaling is certainly to be considered as a contributing factor in AD pathogenesis (Costa et al. 2003, 2005; Ge et al. 2004; Presente et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2004). Nevertheless, reduced function in certain signaling pathways may be a secondary contributing factor in the early-onset AD cases associated with presenilin mutations, although they cause no other known medical consequences.

Aside from onset in middle age and dominant genetic inheritance, the relatively rare familial AD cases mostly display essentially the same progression of symptoms and the same plaque and tangle pathology as late-onset sporadic AD. Thus, the clear involvement of Aβ in familial AD also implicates this peptide in the pathogenesis of the much more common sporadic form of the disease. As the presenilin-containing γ-secretase complex carries out the proteolysis that determines the carboxyl terminus of Aβ and the critical Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, the protease complex is likewise implicated in the pathogenic pathway of sporadic AD. That being said, there is little evidence that the structure and properties of presenilin/γ-secretase are different in sporadic AD patients versus non-AD controls, or that sporadic AD involves specific changes in the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio that are produced by γ-secretase. Nevertheless, it remains possible that local cellular changes alter APP proteolysis by γ-secretase to produce longer forms of Aβ. For instance, environmental factors such as diet may influence membrane composition to elicit such changes. Whether or not such speculations are ultimately borne out, all Aβ is produced via the γ-secretase complex, which makes the protease critical to the disease process. Without γ-secretase-mediated production of Aβ, the disease process should not occur.

In addition to its role in Aβ generation and AD, presenilin/γ-secretase is an essential component of the Notch signaling pathway, as noted earlier. As Notch signaling often keeps precursor cells in a dividing, less specialized state, overactivation of this pathway can cause cancer. Indeed, mutations in Notch are implicated in various forms of cancer (Shih Ie and Wang 2007). These mutations result in a Notch protein that can signal even in the absence of its cognate protein ligand (such as Delta and Jagged). For instance, a chromosomal translocation that results in a truncated, constitutively active form of Notch1 is found in rare cases of human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (Ellisen et al. 1991; Grabher et al. 2006), whereas activating point mutations in Notch1 have been found in 50% of all T-ALL (Weng et al. 2004). Elevation of Notch3 expression is implicated in subsets of non-small-cell lung cancer (Dang et al. 2000) and ovarian cancer (Park et al. 2006), and activation of Notch signaling is also implicated in breast cancer (Hu et al. 2006). For this reason, γ-secretase is considered a potential anticancer target, i.e., blocking the overactivated Notch signaling pathway by preventing the release of the Notch intracellular domain, a transcriptional activator (e.g., Tammam et al. 2009). However, some cancer-causing Notch mutations bypass γ-secretase altogether, producing a truncated form of the receptor comprised of only the intracellular domain (i.e., not membrane localized) (Pear and Aster 2004). Thus, knowledge of the specific Notch mutations in individual patients would be critical in deciding whether to use a γ-secretase inhibitor to treat cancers. In contrast, in the skin, Notch acts as a tumor suppressor, and γ-secretase inhibition can cause skin cancer by interfering with Notch signaling (Demehri et al. 2009) (see below). This further complicates the use of such inhibitors to treat other types of cancer that involve Notch overactivation.

γ-SECRETASE AS A DRUG TARGET

Because the presenilin-containing γ-secretase complex plays an essential role in producing the Aβ peptide, considerable efforts have gone into the discovery and development of small-molecule inhibitors as potential therapeutics for AD. Early inhibitors were useful chemical tools for characterizing γ-secretase as an aspartyl protease (Wolfe et al. 1999a; Shearman et al. 2000), for labeling presenilin to provide evidence that the active site resides at the interface between PS1 NTF and CTF (Esler et al. 2000; Li et al. 2000), for purification of the protease complex (Esler et al. 2002; Beher et al. 2003; Fraering et al. 2004b), and for addressing its mechanism of action (Esler et al. 2002; Kornilova et al. 2005). Most of these compounds, however, were peptidomimetics with poor druglike qualities. The development of inhibitors with better in vivo activity led to the demonstration of Aβ lowering in the brains of transgenic mice overexpressing AD-associated human APP mutants (Dovey et al. 2001; Lanz et al. 2004). However, treatment over an extended period (e.g., 2 wk) resulted in gastrointestinal toxicity and immunosuppression, owing to interference with the Notch signaling pathway (Searfoss et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2004).

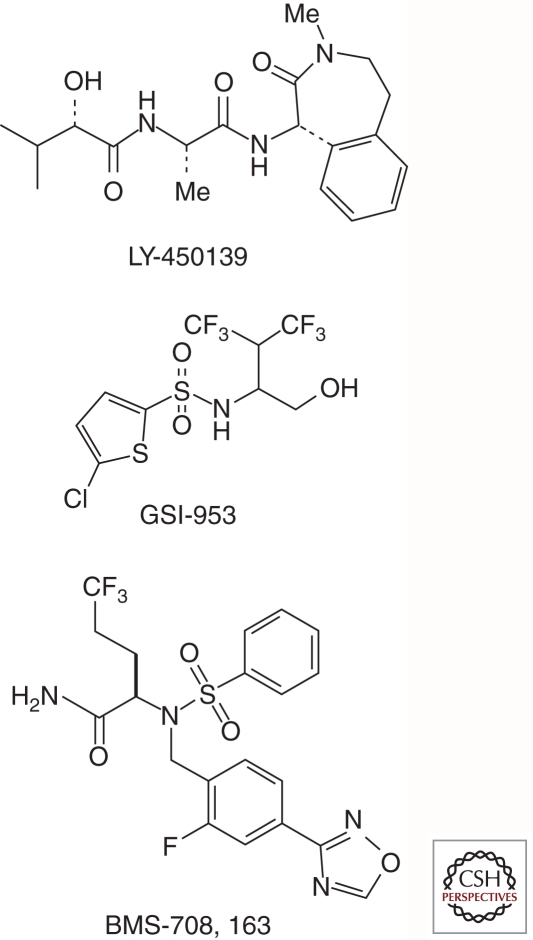

Other evidence shows that, in contrast to its role in cell proliferation in many other cell types, Notch signaling acts as a tumor suppressor in epithelia (Nicolas et al. 2003; Proweller et al. 2006; Demehri et al. 2009), and that reduction of γ-secretase components can result in skin cancers (Xia et al. 2001; Li et al. 2007). Indeed, it has become clear that compounds targeting γ-secretase for the potential treatment of AD should alter Aβ production without significantly lowering the normal, physiologically regulated release of the Notch intracellular domain. The γ-secretase inhibitor that had advanced the furthest in clinical trials, LY450139 (semagacestat; Fig. 5) from Eli Lilly (Fleisher et al. 2008), displayed very little, if any, selectivity for APP compared to Notch, raising concern that doses that effectively lower brain Aβ production would cause systemic toxicity owing to inhibition of Notch signaling. Indeed, a phase 3 trial of this compound was halted owing to increased incidences of skin cancer, GI side effects, and some worsening of cognitive function.

Figure 5.

γ-Secretase inhibitors recently or currently in clinical trials for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. LY450139 shows little selectivity for APP with respect to the Notch receptor, whereas GSI-953 and BMS-708,163 are clearly selective.

Two general classes of compounds targeting γ-secretase have been found to alter Aβ production with varying degrees of selectivity with respect to Notch. The first are so-called γ-secretase modulators, which do not inhibit Aβ production, but instead shift production away from the more aggregation-prone Aβ42 and increase formation of a more soluble 38-residue form (Aβ38). These γ-secretase modulators are exemplified by a subset of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (such as ibuprofen and sulindac sulfide) that were the first compounds discovered to alter the γ-secretase processing of APP in this therapeutically important manner (Weggen et al. 2001). Only certain NSAIDs display this property, and in a manner that does not depend on inhibition of cyclooxygenase (the target of NSAIDs that mediates their antiinflammatory activity). The first compound in this class to enter into clinical trials, R-flurbiprofen (tarenflurbil, Flurizan), is a single enantiomer of a clinically approved racemic NSAID (Eriksen et al. 2003; Galasko et al. 2007; Kukar et al. 2007). Unlike its mirror image, R-flurbiprofen does not inhibit cyclooxygenase, but it nevertheless retains the ability to lower Aβ42. This drug candidate, however, eventually failed owing to lack of efficacy (Green et al. 2009), a result that was not surprising given the very poor potency and brain penetration of this agent. Other compounds with similar properties, but that are much more potent, are in various stages of development. How these compounds elicit their effects is unclear. Some evidence suggests that the compounds selectively target the APP substrate (Kukar et al. 2008), whereas other studies suggest a direct interaction with the protease complex, even in the absence of substrate (Beher et al. 2004). The former mode of interaction (substrate targeting) would be unusual, while the latter mode (allosteric inhibition) is more common.

The second class of therapeutically promising molecules is the so-called “Notch-sparing” γ-secretase inhibitors. These compounds are capable of decreasing the proteolysis of APP by γ-secretase (and thereby decreasing the production of all forms of Aβ) while allowing the enzyme to continue processing the Notch receptor. Early compounds reported with this property were weak inhibitors identified by screening kinase inhibitors: The screen was based on the finding that the γ-secretase complex contains an ATP-binding site that affects the processing of APP but not that of Notch (Fraering et al. 2005). As kinase inhibitors typically interact with ATP-binding sites, the thought was that some kinase inhibitors might interact with an ATP-binding site on γ-secretase. The abl kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec) was the first reported Notch-sparing γ-secretase inhibitor, doing so in an abl kinase-independent manner (Netzer et al. 2003). Recent affinity isolation of the imatinib target apparently responsible for the Aβ-lowering effects identified γ-secretase activating protein (GSAP), a novel 16 kDa protein that can interact stably with the γ-secretase complex (He et al. 2010).

Since the identification of these initial, weak agents, a number of much more potent Notch-sparing inhibitors have been reported, with several that are currently in early- to mid-stage clinical trials (Kreft et al. 2009). These include BMS-708,163 (Fig. 5) from Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS) (Gillman et al. 2010), PF-3,084,014 from Pfizer (Lanz et al. 2010), and GSI-953 (begacestat; Fig. 5) from Wyeth (now part of Pfizer) (Mayer et al. 2008). The Wyeth compound displays nanomolar potency but only 14-fold selectivity for APP over Notch, which may not be sufficient to avoid peripheral Notch-related toxicities. The BMS and Pfizer compounds are both highly potent (nanomolar to subnanomolar) and selective (∼200- to 300-fold); however, it is still unclear whether this selectivity will be sufficient if the compounds do not have high brain penetration.

Avoiding interference with γ-secretase proteolysis of Notch could provide compounds that will have other toxicities that had been masked by the Notch-deficient phenotypes. As mentioned earlier, γ-secretase cleaves many type I membrane proteins after ectodomain release by cell surface sheddases (Beel and Sanders 2008). In some cases, proteolysis of the substrate results in a signaling event or other specific cellular function, for example, the γ-secretase proteolysis of N-cadherin (Marambaud et al. 2003) mentioned earlier. Also, neuregulin-1-triggered γ-secretase cleavage of ErbB4 inhibits astrocyte differentiation by interacting with repressors of astrocyte gene expression (Sardi et al. 2006). It is presently unclear whether interference with these cellular functions will result in toxicity in vivo. In other cases, however, proteolysis of a substrate by γ-secretase may not serve a specific cellular function but may simply be a means of clearing the membrane of protein stubs left behind after ectodomain shedding (Kopan and Ilagan 2004). Although this might appear to be an essential housekeeping function, no general mechanism-based cell toxicity has been observed from γ-secretase inhibitors, perhaps owing to redundant function by other membrane-embedded proteases. Another important issue is selectivity with respect to the family of presenilin homologs exemplified by signal peptide peptidase (Golde et al. 2009). Such “off-target” interactions could also result in toxicity in vivo.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Since the discovery of PSEN mutations associated with early-onset AD in 1995, our understanding of the nature of the γ-secretase complex and the normal and pathological functions of presenilins has come far. Challenges for the future include elucidating the detailed structure of this 19-TMD complex and translating our understanding into practical therapeutics for AD. The hope is that a second edition of this collection will describe major advances on these and other research fronts, and perhaps even some success in the clinic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.D. is Arthur Bax and Anna Vanluffelen chair for Alzheimer disease research, and is supported by a Methusalem grant from the K.U. Leuven and the Flemisch government, by the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO-V), the Foundation for Alzheimer Research (SAO/FRMA), and the Interuniversity Attraction Pole Program (IAP P6/43) of the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office. T.I. is Professor of Neuropathology and supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, and by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology of Japan. M.S.W. is Professor of Neurology and is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Health Assistance Foundation.

Footnotes

Editors: Dennis J. Selkoe, Eckhard Mandelkow, and David M. Holtzman

Additional Perspectives on The Biology of Alzheimer Disease available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Group 1995. The structure of the presenilin 1 (S182) gene and identification of six novel mutations in early onset AD families. Nat Genet 11: 219–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann K, Paganetti PA, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Wong C, Hartmann H, Cescato R, Frey P, Yankner BA, Sommer B, Staufenbiel M 1997. Distinct processing of endogenous and overexpressed recombinant presenilin 1. Neurobiol Aging 18: 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beel AJ, Sanders CR 2008. Substrate specificity of γ-secretase and other intramembrane proteases. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 1311–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beher D, Fricker M, Nadin A, Clarke EE, Wrigley JD, Li YM, Culvenor JG, Masters CL, Harrison T, Shearman MS 2003. In vitro characterization of the presenilin-dependent γ-secretase complex using a novel affinity ligand. Biochemistry 427: 8133–8142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beher D, Clarke EE, Wrigley JD, Martin AC, Nadin A, Churcher I, Shearman MS 2004. Selected non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and their derivatives target γ-secretase at a novel site. Evidence for an allosteric mechanism. J Biol Chem 279: 43419–43426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentahir M, Nyabi O, Verhamme J, Tolia A, Horre K, Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, De Strooper B 2006. Presenilin clinical mutations can affect γ-secretase activity by different mechanisms. J Neurochem 96: 732–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP 2008. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci 31: 454–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, Prada CM, Kim G, Seekins S, Yager D, et al. 1996. Familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Aβ1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 17: 1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, van Lare J, Lee MK, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Sisodia SS 1997. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron 19: 939–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell A, Kaether C, Edbauer D, Shirotani K, Merkl S, Steiner H, Haass C 2003. Nicastrin interacts with γ-secretase complex components via the N-terminal part of its transmembrane domain. J Biol Chem 278: 52519–52523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SL, Mayne M, Holden CP, Geiger JD, Mattson MP 2000. Presenilin-1 mutations increase levels of ryanodine receptors and calcium release in PC12 cells and cortical neurons. J Biol Chem 275: 18195–18200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Hasegawa H, Schmitt-Ulms G, Kawarai T, Bohm C, Katayama T, Gu Y, Sanjo N, Glista M, Rogaeva E, et al. 2006. TMP21 is a presenilin complex component that modulates γ-secretase but not ε-secretase activity. Nature 440: 1208–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KH, Shineman D, Muller M, Cardenas C, Mei L, Yang J, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Lee VM, Foskett JK 2008. Mechanism of Ca2+ disruption in Alzheimer’s disease by presenilin regulation of InsP3 receptor channel gating. Neuron 58: 871–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang PM, Fortna RR, Price DL, Li T, Wong PC 2010. Specific domains in anterior pharynx-defective 1 determine its intramembrane interactions with nicastrin and presenilin. Neurobiol Aging 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Westaway D, Xia W, Carlson G, Diehl T, Levesque G, Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Seubert P, Davis A, et al. 1997. Mutant presenilins of Alzheimer’s disease increase production of 42-residue amyloid β-protein in both transfected cells and transgenic mice. Nat Med 3: 67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RM, Honjo T, Silva AJ 2003. Learning and memory deficits in Notch mutant mice. Curr Biol 13: 1348–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RM, Drew C, Silva AJ 2005. Notch to remember. Trends Neurosci 28: 429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal AS, Morais VA, Pierson TC, Pijak DS, Carlin D, Lee VM, Doms RW 2003. Membrane topology of γ-secretase component PEN-2. J Biol Chem 278: 20117–20123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang TP, Gazdar AF, Virmani AK, Sepetavec T, Hande KR, Minna JD, Roberts JR, Carbone DP 2000. Chromosome 19 translocation, overexpression of Notch3, and human lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1355–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejaegere T, Serneels L, Schafer MK, Van Biervliet J, Horre K, Depboylu C, Alvarez-Fischer D, Herreman A, Willem M, Haass C, et al. 2008. Deficiency of Aph1B/C-γ-secretase disturbs Nrg1 cleavage and sensorimotor gating that can be reversed with antipsychotic treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 9775–9780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demehri S, Turkoz A, Kopan R 2009. Epidermal Notch1 loss promotes skin tumorigenesis by impacting the stromal microenvironment. Cancer Cell 16: 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B 2003. Aph-1, Pen-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active γ-secretase complex. Neuron 38: 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F 1998. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature 391: 387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Schrijvers V, Wolfe MS, Ray WJ, et al. 1999. A presenilin-1-dependent γ-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature 398: 518–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan A, Thinakaran G, Borchelt DR, Slunt HH, Ratovitsky T, Podlisny M, Selkoe DJ, Seeger M, Gand SE, Price DL, et al. 1996. Protein topology of presenilin 1. Neuron 17: 1023–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerfler P, Shearman MS, Perlmutter RM 2001. Presenilin-dependent γ-secretase activity modulates thymocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 9312–9317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey HF, John V, Anderson JP, Chen LZ, de Saint Andrieu P, Fang LY, Freedman SB, Folmer B, Goldbach E, Holsztynska EJ, et al. 2001. Functional γ-secretase inhibitors reduce β-amyloid peptide levels in brain. J Neurochem 76: 173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff K, Eckman C, Zehr C, Yu X, Prada CM, Perez-tur J, Hutton M, Buee L, Harigaya Y, Yager D, et al. 1996. Increased amyloid-β42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature 383: 710–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbauer D, Winkler E, Regula JT, Pesold B, Steiner H, Haass C 2003. Reconstitution of γ-secretase activity. Nat Cell Biol 5: 486–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert S, Paliga K, Soba P, Evin G, Masters CL, Weidemann A, Beyreuther K 2004. The proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein gene family members APLP-1 and APLP-2 involves α-, β-, γ-, and ε-like cleavages: Modulation of APLP-1 processing by n-glycosylation. J Biol Chem 279: 18146–18156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynolds TC, Smith SD, Sklar J 1991. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell 66: 649–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Smith TE, Weggen S, Das P, McLendon DC, Ozols VV, Jessing KW, Zavitz KH, Koo EH, et al. 2003. NSAIDs and enantiomers of flurbiprofen target γ-secretase and lower Aβ 42 in vivo. J Clin Invest 112: 440–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler WP, Kimberly WT, Ostaszewski BL, Diehl TS, Moore CL, Tsai J-Y, Rahmati T, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS 2000. Transition-state analogue inhibitors of γ-secretase bind directly to presenilin-1. Nature Cell Biol 2: 428–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler WP, Kimberly WT, Ostaszewski BL, Ye W, Diehl TS, Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS 2002. Activity-dependent isolation of the presenilin/γ-secretase complex reveals nicastrin and a γ substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 2720–2725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esselens C, Oorschot V, Baert V, Raemaekers T, Spittaels K, Serneels L, Zheng H, Saftig P, De Strooper B, Klumperman J, et al. 2004. Presenilin 1 mediates the turnover of telencephalin in hippocampal neurons via an autophagic degradative pathway. J Cell Biol 166: 1041–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher AS, Raman R, Siemers ER, Becerra L, Clark CM, Dean RA, Farlow MR, Galvin JE, Peskind ER, Quinn JF, et al. 2008. Phase 2 safety trial targeting amyloid β production with a γ-secretase inhibitor in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 65: 1031–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood DG, Reaume AG, Dorfman KS, Lin YG, Lang DM, Trusko SP, Savage MJ, Annaert WG, De Strooper B, Siman R, et al. 2002. FAD mutant PS-1 gene-targeted mice: Increased Aβ42 and Aβ deposition without APP overproduction. Neurobiol Aging 23: 335–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortna RR, Crystal AS, Morais VA, Pijak DS, Lee VM, Doms RW 2004. Membrane topology and nicastrin-enhanced endoproteolysis of APH-1, a component of the γ-secretase complex. J Biol Chem 279: 3685–3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraering PC, LaVoie MJ, Ye W, Ostaszewski BL, Kimberly WT, Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS 2004a. Detergent-dependent dissociation of active γ-secretase reveals an interaction between Pen-2 and PS1-NTF and offers a model for subunit organization within the complex. Biochemistry 43: 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraering PC, Ye W, Strub JM, Dolios G, LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Van Dorsselaer A, Wang R, Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS 2004b. Purification and characterization of the human γ-Secretase complex. Biochemistry 43: 9774–9789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraering PC, Ye W, Lavoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS 2005. γ-Secretase substrate selectivity can be modulated directly via interaction with a nucleotide binding site. J Biol Chem 280: 41987–41996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R, McGrath G, Zhang J, Ruddy DA, Sym M, Apfeld J, Nicoll M, Maxwell M, Hai B, Ellis MC, et al. 2002. aph-1 and pen-2 are required for Notch pathway signaling, γ-secretase cleavage of βAPP, and presenilin protein accumulation. Dev Cell 3: 85–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumori A, Fluhrer R, Steiner H, Haass C 2010. Three-amino acid spacing of presenilin endoproteolysis suggests a general stepwise cleavage of γ-secretase-mediated intramembrane proteolysis. J Neurosci 30: 7853–7862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko DR, Graff-Radford N, May S, Hendrix S, Cottrell BA, Sagi SA, Mather G, Laughlin M, Zavitz KH, Swabb E, et al. 2007. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and Aβ levels after short-term administration of R-flurbiprofen in healthy elderly individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21: 292–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Hannan F, Xie Z, Feng C, Tully T, Zhou H, Xie Z, Zhong Y 2004. Notch signaling in Drosophila long-term memory formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 10172–10176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos A, Marambaud P, Efthimiopoulos S, Shioi J, Cui W, Li HC, Schutte M, Gordon R, Holstein GR, Martinelli G, et al. 1999. Presenilin-1 forms complexes with the cadherin/catenin cell-cell adhesion system and is recruited to intercellular and synaptic contacts. Mol Cell 4: 893–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman KW, Starrett JE, Parker MF, Xie K, Bronson JJ, Marcin LR, McElhone KE, Bergstrom CP, Mate RA, Williams R, et al. 2010. Discovery and evaluation of BMS-708163, a potent, selective and orally bioavailable γ-secretase inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett 1: 120–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE, Wolfe MS, Greenbaum DC 2009. Signal peptide peptidases: A family of intramembrane-cleaving proteases that cleave type 2 transmembrane proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol 20: 225–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutte C, Hepler W, Mickey KM, Priess JR 2000. aph-2 encodes a novel extracellular protein required for GLP-1-mediated signaling. Development 127: 2481–2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutte C, Tsunozaki M, Hale VA, Priess JR 2002. APH-1 is a multipass membrane protein essential for the Notch signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 775–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabher C, von Boehmer H, Look AT 2006. Notch 1 activation in the molecular pathogenesis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer 6: 347–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KN, Demuro A, Akbari Y, Hitt BD, Smith IF, Parker I, LaFerla FM 2008. SERCA pump activity is physiologically regulated by presenilin and regulates amyloid-β production. J Cell Biol 181: 1107–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Schneider LS, Amato DA, Beelen AP, Wilcock G, Swabb EA, Zavitz ZH 2009. Effect of tarenflurbil on cognitive decline and activities of daily living in patients with mild Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302: 2557–2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Chen F, Sanjo N, Kawarai T, Hasegawa H, Duthie M, Li W, Ruan X, Luthra A, Mount HT, et al. 2003. APH-1 interacts with mature and immature forms of presenilins and nicastrin and may play a role in maturation of presenilin.nicastrin complexes. J Biol Chem 278: 7374–7380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Selkoe DJ 1993. Cellular processing of β-amyloid precursor protein and the genesis of amyloid β-peptide. Cell 75: 1039–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Selkoe DJ 1998. Alzheimer’s disease. A technical KO of amyloid-β peptide. Nature 391: 339–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Haass C, Kaether C, Sisodia S, Thinakaran G 2011. Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a006270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland BK, Manley NR, Su D, Longmore GD, Moore CL, Wolfe MS, Schroeter EH, Kopan R 2001. γ-secretase inhibitors repress thymocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 7487–7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayrapetyan V, Rybalchenko V, Rybalchenko N, Koulen P 2008. The N-terminus of presenilin-2 increases single channel activity of brain ryanodine receptors through direct protein-protein interaction. Cell Calcium 44: 507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Luo W, Li P, Remmers C, Netzer WJ, Hendrick J, Bettayeb K, Flajolet M, Gorelick F, Wennogle LP, et al. 2010. γ-secretase activating protein is a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 467: 95–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming ML, Elias JE, Gygi SP, Selkoe DJ 2008. Proteomic profiling of γ-secretase substrates and mapping of substrate requirements. PLoS Biol 6: e257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Dievart A, Lupien M, Calvo E, Tremblay G, Jolicoeur P 2006. Overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 in transgenic mice blocks mammary gland development and induces mammary tumors. Am J Pathol 168: 973–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaether C, Capell A, Edbauer D, Winkler E, Novak B, Steiner H, Haass C 2004. The presenilin C-terminus is required for ER-retention, nicastrin-binding and γ-secretase activity. Embo J 23: 4738–4748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasri NN, Kocks SL, Verbert L, Hebert SS, Callewaert G, Parys JB, Missiaen L, De Smedt H 2006. Up-regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 is responsible for a decreased endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+ content in presenilin double knock-out cells. Cell Calcium 40: 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal A, Chandu D, Roe CM, Kopan R, Quatrano RS 2007. Moonlighting activity of presenilin in plants is independent of γ-secretase and evolutionarily conserved. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 13337–13342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Sisodia SS 2005. Evidence that the “NF” motif in transmembrane domain 4 of presenilin 1 is critical for binding with PEN-2. J Biol Chem 280: 41953–41966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly WT, LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Ye W, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ 2003. γ-Secretase is a membrane protein complex comprised of presenilin, nicastrin, aph-1, and pen-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 6382–6387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Ilagan MX 2004. γ-Secretase: Proteasome of the membrane?. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornilova AY, Bihel F, Das C, Wolfe MS 2005. The initial substrate binding site of γ-secretase is located on presenilin near the active site. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 3230–3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft AF, Martone R, Porte A 2009. Recent advances in the identification of γ-secretase inhibitors to clinically test the Aβ oligomer hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Chem 52: 6169–6188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukar T, Prescott S, Eriksen JL, Holloway V, Murphy MP, Koo EH, Golde TE, Nicolle MM 2007. Chronic administration of R-flurbiprofen attenuates learning impairments in transgenic amyloid precursor protein mice. BMC Neurosci 8: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukar TL, Ladd TB, Bann MA, Fraering PC, Narlawar R, Maharvi GM, Healy B, Chapman R, Welzel AT, Price RW, et al. 2008. Substrate-targeting γ-secretase modulators. Nature 453: 925–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulic L, Walter J, Multhaup G, Teplow DB, Baumeister R, Romig H, Capell A, Steiner H, Haass C 2000. Separation of presenilin function in amyloid β-peptide generation and endoproteolysis of Notch. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97: 5913–5918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Hosley JD, Adams WJ, Merchant KM 2004. Studies of Aβ pharmacodynamics in the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and plasma in young (plaque-free) Tg2576 mice using the γ-secretase inhibitor N2-[(2S)-2-(3,5-difluorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethanoyl]-N1-[(7S)-5-methyl-6-oxo-6,7-di hydro-5H-dibenzo[b,d]azepin-7-yl]-L-alaninamide (LY-411575). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 309: 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Wood KM, Richter KE, Nolan CE, Becker SL, Pozdnyakov N, Martin BA, Du P, Oborski CE, Wood DE, et al. 2010. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the γ-secretase inhibitor, PF-3084014. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334: 269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudon H, Hansson EM, Melen K, Bergman A, Farmery MR, Winblad B, Lendahl U, von Heijne G, Naslund J 2005. A nine-transmembrane domain topology for presenilin 1. J Biol Chem 280: 35352–35360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie MJ, Fraering PC, Ostaszewski BL, Ye W, Kimberly WT, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ 2003. Assembly of the γ-secretase complex involves early formation of an intermediate subcomplex of Aph-1 and nicastrin. J Biol Chem 278: 37213–37222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov VK, Fraering PC, Ye W, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ, Li H 2006. Electron microscopic structure of purified, active γ-secretase reveals an aqueous intramembrane chamber and two pores. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 6889–6894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Yu WH, Kumar A, Lee S, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Wolfe DM, Martinez-Vicente M, Massey AC, Sovak G, et al. 2010. Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 141: 1146–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leissring MA, Paul BA, Parker I, Cotman CW, LaFerla FM 1999. Alzheimer’s presenilin-1 mutation potentiates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated calcium signaling in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurochem 72: 1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan D, Greenwald I 1995. Facilitation of lin-12-mediated signalling by sel-12, a Caenorhabditis elegans S182 Alzheimer’s disease gene. Nature 377: 351–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan D, Yu G, St George Hyslop P, Goutte C 2001. APH-2/nicastrin functions in LIN-12/Notch signaling in the Caenorhabditis elegans somatic gonad. Dev Biol 240: 654–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, Yu CE, Jondro PS, Schmidt SD, Wang K, et al. 1995. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer’s disease locus. Science 269: 973–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YM, Xu M, Lai MT, Huang Q, Castro JL, DiMuzio-Mower J, Harrison T, Lellis C, Nadin A, Neduvelil JG, et al. 2000. Photoactivated γ-secretase inhibitors directed to the active site covalently label presenilin 1. Nature 405: 689–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Wen H, Brayton C, Das P, Smithson LA, Fauq A, Fan X, Crain BJ, Price DL, Golde TE, et al. 2007. Epidermal growth factor receptor and notch pathways participate in the tumor suppressor function of γ-secretase. J Biol Chem 282: 32264–32273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G, Li T, Price DL, Wong PC 2005. APH-1a is the principal mammalian APH-1 isoform present in γ-secretase complexes during embryonic development. J Neurosci 25: 192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P, Shioi J, Serban G, Georgakopoulos A, Sarner S, Nagy V, Baki L, Wen P, Efthimiopoulos S, Shao Z, et al. 2002. A presenilin-1/γ-secretase cleavage releases the E-cadherin intracellular domain and regulates disassembly of adherens junctions. Embo J 21: 1948–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P, Wen PG, Dutt A, Shioi J, Takashima A, Siman R, Robakis NK 2003. A CBP binding transcriptional repressor produced by the PS1/ε-cleavage of N-cadherin is inhibited by PS1 FAD mutations. Cell 114: 635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SC, Kreft AF, Harrison B, Abou-Gharbia M, Antane M, Aschmies S, Atchison K, Chlenov M, Cole DC, Comery T, et al. 2008. Discovery of begacestat, a Notch-1-sparing γ-secretase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Chem 51: 7348–7351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JV, Twomey C, Wujek P 2009. Presenilin-dependent regulated intramembrane proteolysis and γ-secretase activity. Cell Mol Life Sci 66: 1534–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehlmann T, Winkler E, Xia X, Edbauer D, Murrell J, Capell A, Kaether C, Zheng H, Ghetti B, Haass C, et al. 2002. Presenilin-1 mutations of leucine 166 equally affect the generation of the Notch and APP intracellular domains independent of their effect on Aβ 42 production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 8025–8030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mucke L 2011. Neurotoxicity of amyloid β-protein: Synaptic and network dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a006338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Müller UC, Zheng H 2011. Physiological functions of APP family proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a006288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruse S, Thinakaran G, Luo JJ, Kusiak JW, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Qian X, Ginty DD, Price DL, Borchelt DR, et al. 1998. Effects of PS1 deficiency on membrane protein trafficking in neurons. Neuron 21: 1213–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson O, Tu H, Lei T, Bentahir M, de Strooper B, Bezprozvanny I 2007. Familial Alzheimer disease-linked mutations specifically disrupt Ca2+ leak function of presenilin 1. J Clin Invest 117: 1230–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer WJ, Dou F, Cai D, Veach D, Jean S, Li Y, Bornmann WG, Clarkson B, Xu H, Greengard P 2003. Gleevec inhibits β-amyloid production but not Notch cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 12444–12449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas M, Wolfer A, Raj K, Kummer JA, Mill P, van Noort M, Hui CC, Clevers H, Dotto GP, Radtke F 2003. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in mouse skin. Nat Genet 33: 416–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyabi O, Bentahir M, Horre K, Herreman A, Gottardi-Littell N, Van Broeckhoven C, Merchiers P, Spittaels K, Annaert W, De Strooper B 2003. Presenilins mutated at Asp-257 or Asp-385 restore Pen-2 expression and Nicastrin glycosylation but remain catalytically inactive in the absence of wild type Presenilin. J Biol Chem 278: 43430–43436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T, Mio K, Hayashi I, Miyashita H, Fukuda R, Kopan R, Kodama T, Hamakubo T, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, et al. 2006. Three-dimensional structure of the γ-secretase complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343: 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osenkowski P, Li H, Ye W, Li D, Aeschbach L, Fraering PC, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ, Li H 2009. Cryoelectron microscopy structure of purified γ-secretase at 12 A resolution. J Mol Biol 385: 642–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardossi-Piquard R, Yang SP, Kanemoto S, Gu Y, Chen F, Bohm C, Sevalle J, Li T, Wong PC, Checler F, et al. 2009. APH1 polar transmembrane residues regulate the assembly and activity of presenilin complexes. J Biol Chem 284: 16298–16307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JT, Li M, Nakayama K, Mao TL, Davidson B, Zhang Z, Kurman RJ, Eberhart CG, Shih Ie M, Wang TL 2006. Notch3 gene amplification in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 66: 6312–6318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear WS, Aster JC 2004. T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma: A human cancer commonly associated with aberrant NOTCH1 signaling. Curr Opin Hematol 11: 426–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting CP, Hutton M, Nyborg A, Baker M, Jansen K, Golde TE 2002. Identification of a novel family of presenilin homologues. Hum Mol Genet 11: 1037–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presente A, Boyles RS, Serway CN, de Belle JS, Andres AJ 2004. Notch is required for long-term memory in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 1764–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proweller A, Tu L, Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Lu MM, Seykora J, Millar SE, Pear WS, Parmacek MS 2006. Impaired notch signaling promotes de novo squamous cell carcinoma formation. Cancer Res 66: 7438–7444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qyang Y, Chambers SM, Wang P, Xia X, Chen X, Goodell MA, Zheng H 2004. Myeloproliferative disease in mice with reduced presenilin gene dosage: Effect of γ-secretase blockage. Biochemistry 43: 5352–5359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard C, Hebert SS, De Strooper B 2005. The amyloid-β precursor protein: Integrating structure with biological function. EMBO J 24: 3996–4006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto E, Yoon IS, Zheng H, Kang DE 2007. Presenilin 1 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor turnover and signaling in the endosomal-lysosomal pathway. J Biol Chem 282: 31504–31516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaev EI, Sherrington R, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Liang Y, Chi H, Lin C, Holman K, Tsuda T, et al. 1995. Familial Alzheimer’s disease in kindreds with missense mutations in a gene on chromosome 1 related to the Alzheimer’s disease type 3 gene. Nature 376: 775–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi SP, Murtie J, Koirala S, Patten BA, Corfas G 2006. Presenilin-dependent ErbB4 nuclear signaling regulates the timing of astrogenesis in the developing brain. Cell 127: 185–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato C, Morohashi Y, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T 2006. Structure of the catalytic pore of γ-secretase probed by the accessibility of substituted cysteines. J Neurosci 26: 12081–12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Diehl TS, Narayanan S, Funamoto S, Ihara Y, De Strooper B, Steiner H, Haass C, Wolfe MS 2007. Active γ-secretase complexes contain only one of each component. J Biol Chem 282: 33985–33993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato C, Takagi S, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T 2008. The C-terminal PAL motif and transmembrane domain 9 of presenilin 1 are involved in the formation of the catalytic pore of the γ-secretase. J Neurosci 28: 6264–6271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura CA, Choi SY, Beglopoulos V, Malkani S, Zhang D, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Chattarji SRS, Kelleher RJ III, Kandel ER, Duff K, et al. 2004. Loss of presenilin function causes impairments of memory and synaptic plasticity followed by age-dependent neurodegeneration. Neuron 42: 23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savonenko AV, Melnikova T, Laird FM, Stewart KA, Price DL, Wong PC 2008. Alteration of BACE1-dependent NRG1/ErbB4 signaling and schizophrenia-like phenotypes in BACE1-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 5585–5590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeld MH, Ghersi E, Laky K, Fowlkes BJ, D’Adamio L 2002. Processing of β-amyloid precursor-like protein-1 and -2 by γ-secretase regulates transcription. J Biol Chem 277: 44195–44201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, Bird TD, Hardy J, Hutton M, Kukull W, et al. 1996. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 2: 864–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter EH, Ilagan MX, Brunkan AL, Hecimovic S, Li YM, Xu M, Lewis HD, Saxena MT, De Strooper D, Coonrod A, et al. 2003. A presenilin dimer at the core of the γ-secretase enzyme: Insights from parallel analysis of Notch 1 and APP proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 13075–13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searfoss GH, Jordan WH, Calligaro DO, Galbreath EJ, Schirtzinger LM, Berridge BR, Gao H, Higgins MA, May PC, Ryan TP 2003. Adipsin: A biomarker of gastrointestinal toxicity mediated by a functional γsecretase inhibitor. J Biol Chem 278: 46107–46116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serneels L, Dejaegere T, Craessaerts K, Horre K, Jorissen E, Tousseyn T, Hebert S, Coolen M, Martens G, Zwijsen A, et al. 2005. Differential contribution of the three Aph1 genes to γ-secretase activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 1719–1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serneels L, Van Biervliet J, Craessaerts K, Dejaegere T, Horre K, Van Houtvin T, Esselmann H, Paul S, Schafer MK, Berezovska O, et al. 2009. γ-Secretase heterogeneity in the Aph1 subunit: Relevance for Alzheimer’s disease. Science 324: 639–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman MS, Beher D, Clarke EE, Lewis HD, Harrison T, Hunt P, Nadin A, Smith AL, Stevenson G, Castro JL 2000. L-685,458, an aspartyl protease transition state mimic, is a potent inhibitor of amyloid β-protein precursor γ-secretase activity. Biochemistry 39: 8698–8704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Kelleher RJ III 2007. The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, et al. 1995. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 375: 754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Ie M, Wang TL 2007. Notch signaling, γ-secretase inhibitors, and cancer therapy. Cancer Res 67: 1879–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirotani K, Edbauer D, Capell A, Schmitz J, Steiner H, Haass C 2003. γ-Secretase activity is associated with a conformational change of nicastrin. J Biol Chem 278: 16474–16477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman R, Reaume AG, Savage MJ, Trusko S, Lin YG, Scott RW, Flood DG 2000. Presenilin-1 P264L knock-in mutation: Differential effects on Aβ production, amyloid deposition, and neuronal vulnerability. J Neurosci 20: 8717–8726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhanifar S, Schneider B, Lohr F, Gottstein F, Ikeya T, Mlynarczyk K, Pulawski W, Ghoshdastider U, Kolinski M, Filipek S, et al. 2010. Structural investigation of the C-terminal catalytic fragment of presenilin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 9644–9649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Nadeau P, Yuan M, Yang X, Shen J, Yankner BA 1999. Proteolytic release and nuclear translocation of Notch-1 are induced by presenilin-1 and impaired by pathogenic presenilin-1 mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 6959–6963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasic D, Tolia A, Dillen K, Baert V, De Strooper B, Vrijens S, Annaert W 2006. Presenilin-1 maintains a nine-transmembrane topology throughout the secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 281: 26569–26577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S, Brynjolfsson J, Gunnarsdottir S, Ivarsson O, Chou TT, et al. 2002. Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 71: 877–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Kostka M, Romig H, Basset G, Pesold B, Hardy JA, Capell A, Meyn L, Grim MG, Baumeister R, et al. 2000. Glycine 384 is required for presenilin-1 function and is conserved in bacterial polytopic aspartyl proteases. Nature Cell Biol 2: 848–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Winkler E, Haass C 2008. Chemical crosslinking provides a model of the γ-secretase complex subunit architecture and evidence for close proximity of the C-terminal fragment of presenilin with APH-1. J Biol Chem 283: 34677–34686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G, Greenwald I 1999. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature 398: 522–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S, Tominaga A, Sato C, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T 2010. Participation of transmembrane domain 1 of presenilin 1 in the catalytic pore structure of the γ-secretase. J Neurosci 30: 15943–15950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasugi N, Tomita T, Hayashi I, Tsuruoka M, Niimura M, Takahashi Y, Thinakaran G, Iwatsubo T 2003. The role of presenilin cofactors in the γ-secretase complex. Nature 422: 438–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammam J, Ware C, Efferson C, O'Neil J, Rao S, Qu X, Gorenstein J, Angagaw M, Kim H, Kenific C, et al. 2009. Down-regulation of the Notch pathway mediated by a γ-secretase inhibitor induces anti-tumour effects in mouse models of T-cell leukaemia. Br J Pharmacol 158: 1183–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi Y, Hur JY, Welander H, Franberg J, Aoki M, Winblad B, Frykman S, Tjernberg LO 2009. Affinity pulldown of γ-secretase and associated proteins from human and rat brain. J Cell Mol Med 14: 2675–2686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]