Abstract

Histamine (HA) is a biogenic amine that mediates multiple physiological processes including immunomodulatory effects in allergic and inflammatory reactions, and also plays a key regulatory role in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), the autoimmune model of multiple sclerosis (MS). The pleiotropic effects of HA are mediated by four G protein-coupled receptors: Hrh1/H1R, Hrh2/H2R, Hrh3/H3R, and Hrh4/H4R. H4R expression is primarily restricted to hematopoietic cells, and its role in autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS has not been studied. In this report we show that, compared to wild type (WT) mice, animals with a disrupted Hrh4 (H4RKO) develop more severe myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35–55 (MOG35-55) peptide-induced EAE. Mechanistically, we also show that H4R plays a role in determining the frequency of T regulatory (TR) cells in secondary lymphoid tissues, and regulates TR cell chemotaxis and suppressor activity. Moreover, the lack of H4R leads to an impairment of an anti-inflammatory response due to fewer TR cells in the CNS during the acute phase of the disease and an increase in the proportion of Th17 cells.

Introduction

Histamine [2-(4-imidazolyl)-ethylamine] (HA) is a biogenic amine that mediates multiple physiological processes, including neurotransmission and brain functions, secretion of pituitary hormones, and regulation of gastrointestinal and circulatory functions (1). Additionally, HA is an important mediator of inflammation and of innate and adaptive immune responses (1, 2). The pleiotropic effects of HA are mediated by four HA receptors (Hrh1/H1R, Hrh2/H2R, Hrh3/H3R, and Hrh4/H4R), all of which belong to the G protein-coupled receptor family (1, 2). These receptors are expressed on multiple cell types and signal through distinct intracellular pathways, which in part explains the diverse effects of HA on different cells and tissues.

Histamine is implicated in the pathogenesis of MS, as well as EAE. HA modulates blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and enhances leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and vascular extravasation of inflammatory cells into the CNS (3, 4). Increased levels of HA in cerebrospinal fluid correlate with relapses in MS patients (5) and with the onset of EAE (6). In addition, transcriptional profiling of MS lesions revealed that H1R expression was upregulated relative to normal tissue (7). Moreover, epidemiological data indicate that use of sedating H1R antagonists is associated with decreased MS risk (8) and in a small study MS patients treated with an H1R antagonist remained stable or improved neurologically (9). Likewise, H1R and H2R transcripts are present in the brain lesions of mice with active EAE, and administration of pyrilamine, a H1R antagonist, reduces EAE severity (10). We previously identified Bordetella pertussis toxin-induced HA sensitization (Bphs) as a susceptibility locus for EAE and experimental allergic orchitis, and positional candidate gene cloning identified Bphs as Hrh1 (11). Further, genetic studies have demonstrated that HA, H1R, H2R and H3R play important roles in disease development and EAE susceptibility either by regulating APC function, the encephalitogenic T cell responses, or BBB permeability (11–14). However, the role of H4R in autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS has not yet been studied.

H4R expression is mostly restricted to hematopoietic cells, including T cells (15). H4R is coupled to second messenger signaling pathways via the pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive heterotrimeric Gi/o proteins (16) and to the β-arrestin pathway (17). The activation of H4R mediates intracellular calcium mobilization, cAMP inhibition, modulation of JAK-STAT, MAPK/ERK and PI3K pathways, and activation of the transcription factor AP-1 (15, 18). As a result, H4R signaling regulates cytokine production, DC function, and Th cell polarization (19). In addition, H4R activation induces actin polymerization, upregulation of adhesion molecules, changes in cell shape, and chemotaxis of different immune cells, including eosinophils, mast cells, Langerhans cells, and T cells (15, 20–22). The role of H4R in the integrated immune response, however, remains unclear. Moreover, the use of different models has led to conflicting results about the role of H4R in the immune response. In the murine model of allergic asthma, Morgan et al reported that the administration of 4-methyl HA (4-mHA), a H4R agonist, reduced airway hyperreactivity and inflammation, while increasing TR cell recruitment to the lung, suggesting an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory role for H4R in this response (23). In contrast, studies using H4RKO mice and H4R antagonists, particularly JNJ 7777120 and its derivatives, suggest a pro-inflammatory role for this receptor in a variety of in vivo models (15, 20, 21). Furthermore, single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variations in human Hrh4 have been reported to be associated with atopic dermatitis (24) and systemic lupus erythematosus (25). Despite conflicting results, the findings of the experiments above underscore the role of H4R in modulating immune responses.

To assess the role of H4R signaling in the regulation of autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS, we studied MOG35-55-induced EAE in H4RKO mice. The results of our study provide direct evidence that H4R modulates EAE severity. We show that H4RKO mice, despite having equivalent T effector (TE) cell responses, develop more severe EAE, augmented neuroinflammation, and increased BBB permeability compared to WT mice. In addition, we show that H4R signaling exerts control over the frequency of TR cell in secondary lymphoid tissues, as well as chemotaxis and suppressive ability of TR cells. Consistent with this, the lack of H4R leads to a lower proportion of these cells in the CNS during the acute effector phase of the disease, leading to an increase in the proportion of CD4+IL17+ cells and impairment of an anti-inflammatory response.

Material and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J (B6/J, WT) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). B6.129P-Hrh4tm1Thr (H4RKO) mice were generated by Lexicon Genetics (Woodlands, TX), and were backcrossed onto B6/J. The N10 mice were intercrossed and resulting mice were used in the experiments. B6-Foxp3gfp KI mice were kindly provided by Dr. Vijay Kuchroo (Center of Neurological Diseases, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). H4RKO-Foxp3gfp KI mice were generated by crossbreeding B6-Foxp3gfp KI mice and H4RKO mice. Mice were housed at 25°C with 12/12-h light-dark cycles and 40–60% humidity. The experimental procedures performed in this study were under the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Vermont (Burlington, VT).

Induction and evaluation of EAE

Mice were immunized for the induction of EAE using a single injection protocol. The animals were injected s.c. in the posterior right and left flank and the scruff of the neck with a sonicated PBS/oil emulsion containing 200 μg of MOG35-55 and CFA (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 200 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco Laboratories). Immediately afterward, each mouse received 200 ng of PTX (List Biological Laboratories) in 0.2 ml of Munoz buffer by i.v. injection (14). Mice were scored daily for clinical quantitative trait variables beginning at day 5 after injection as follows: 0, no clinical expression of disease; 1, flaccid tail without hind limb weakness; 2, hind limb weakness; 3, complete hind limb paralysis and floppy tail; 4, hind leg paralysis accompanied by a floppy tail and urinary or fecal incontinence; 5, moribund. Assessments of clinical quantitative trait variables, EAE pathology, and BBB permeability were performed as previously described (14).

CNS-infiltrating MN cell isolation

Mice were perfused with saline and brain and spinal cord were removed. A single cell suspension was obtained and passed through a 70 μm strainer. MN cells were obtained by Percoll gradient (37%/70%) centrifugation, collected from the interphase and washed. Cells were labeled with Live-Dead UV Blue dye (BD Pharmingen), followed by surface and intracellular staining.

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

The DLN, spleen, and thymus were excised and dissociated into single cell suspensions. For the identification and phenotypic analysis of TR cells (CD4+CD8−TCRβ+Foxp3+), the following surface anti-mouse mAb were used: anti-CD4 (MCD0417, Caltag); anti-CD8, and anti-CD25 (53–6.7, PC61; BD Pharmingen); anti-TCRβ, anti-CCR7, and anti-Foxp3 (H57-5987, 4B12, FJK-16s; eBioscience). Intracellular Foxp3 was stained with the mouse/rat Foxp3 staining set (eBioscience), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For intracellular cytokine staining, CNS-infiltrating MN cells were stimulated with 5 ng/ml of PMA, 250 ng/ml of ionomycin and 2 μM monensin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4h. Cells were first stained with LIVE/DEAD fixable stain (Invitrogen) and anti-CD4-Pacific blue (GK1.5; BioLegend). Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), permeabilized with buffer containing 0.1% saponin and stained with anti-IL17A-PE (TC11-18H10; BD Pharmingen) and anti-IL10-Alexa Fluor 647 (JES5-16E7; BioLegend). Cells were collected using BD LSR II cytometer (BD biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar Software, Inc).

Cell culture conditions and lymphokine assays

For ex vivo cytokine analysis, spleen and DLN were obtained from d10 immunized mice. Single cell suspensions at 1×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro Mediatech) plus 5% FBS (HyClone) were stimulated with 50 μg/ml of MOG35-55. Cell culture supernatants were recovered at 72 h and concentrations of 23 different cytokines were quantified in duplicate by Bio-Plex multiplex cytokine assay (BD Biosciences).

Proliferation assay

Mice were immunized for EAE induction, and DLN and spleens were harvested on d10. Single cell suspensions were prepared, and 5×105 cells/well in RPMI 1640 (5% FBS) were plated on standard 96-well U-bottom tissue culture plates and stimulated with 0, 1, 2, 10 and 50 μg/ml of MOG35-55 for 72 h at 37°C. During the last 18 h of culture, 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine (PerkinElmer) was added. Cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters and thymidine uptake was determined with a liquid scintillation counter.

Suppression assay

CD4+CD25− (TE) and CD4+CD25+ (TR) T cells from LN and spleen were sorted using anti-CD4, anti-TCRβ, and anti-CD25 mAbs. CD4+CD25+ T cell purity was consistently >97%. CD4+CD25− TE cells were cultured for 3 d with irradiated spleen cells as APC (1×105/well) in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb (5 μg/ml), with or without CD4+CD25+ TR cells at 0.5:1 (TR:TE) cell ratio. The cell cultures were pulsed with 0.5 μCi [3H] thymidine for the last 18 hrs. TE cell proliferation with WT TR cells was set at 100%. Percentage of inhibition in the presence of H4RKO TR cells was calculated.

Cell migration assay

Migratory capacity of CD4+ T cells or B6-Foxp3gfp KI or H4RKO-Foxp3gfp KI TR or TE cells was evaluated using 24-well Transwell plates with a 3.0 μm pore size (Costar). Total CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection and TR cells were sorted based on GFP expression. CD4+TCR+ cell purity was >85% and sorted TR cell purity was >97%. One hundred microliters of cells were added to the top well at 1×106 CD4+ T cells or 0.5×106 TR cells in RPMI 1640 with 1% BSA and medium containing either no HA, 10−4 M or 10−7 M HA or 100 ng/ml SDF-1α was added to the bottom chamber. After 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells that migrated to the bottom chamber were harvested, counted, and stained for subsequent flow cytometric analysis.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from TE cells or TR cells from naïve WT and H4RKO mice using RNeasy isolation reagent (Qiagen Inc.), and reverse transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The generated cDNA was used in qRT-PCR using the SYBR green method. The sequences of Hrh4 primers used were as follows: forward, 5′ TGAGGAGAATTGCTTCACGA 3′; reverse, 5′ TGCATGTGGAGGGGTTTTAT 3′. β2-microglobulin was used as a reference gene and the relative expression levels were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad software Inc, San Diego, CA). Significance of differences was determined using parametric and non-parametric tests as described in the Figure Legends. For all analyses, p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

H4R negatively regulates EAE severity

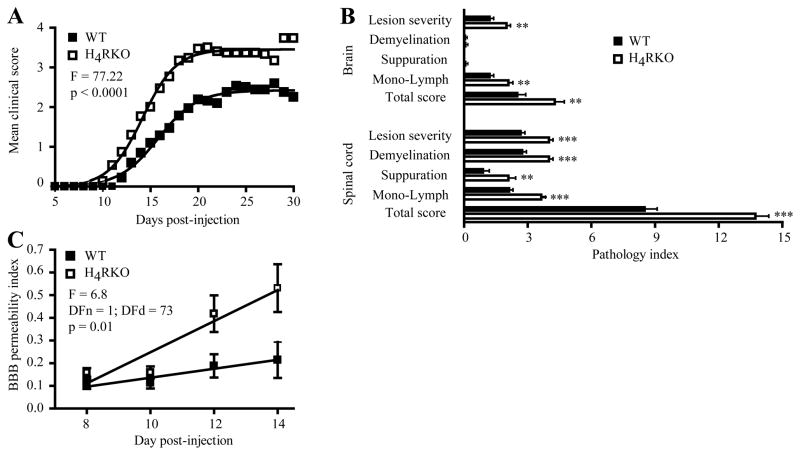

To investigate the role of H4R in autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS, EAE was induced in WT and H4RKO mice by immunization with MOG35-55-CFA-PTX. The clinical disease course of H4RKO mice was more severe than WT mice (Figure 1A). Analysis of EAE-associated clinical traits (14) revealed that the mean day of onset, mean cumulative disease score, days affected, overall severity index, and peak score were significantly greater in H4RKO compared to WT mice (Table I). Furthermore, histopathological analysis revealed more extensive pathology in the brains and spinal cords of H4RKO mice compared to WT mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. H4R negatively regulates EAE severity and BBB permeability.

Clinical score (A) and severity of CNS lesions (B) in WT (■, n=32) and H4RKO (□, n=30) mice were compared following immunization with MOG35-55-CFA-PTX. The significance of the differences between the clinical courses of disease was calculated by regression analysis and best-fit curve is shown. In (B), the significance of differences observed at d30 post-immunization was determined using the Mann-Whitney test (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). (C) The significance of differences in BBB permeability indices of WT and H4RKO mice across the early acute phase of disease was assessed by regression analyses (n=8 for each strain at each time point).

Table I. Summary of EAE clinical trait variables in WT and H4RKO mice.

Animals were immunized with MOG35-55-CFA-PTX and scored daily for clinical signs starting on d5. Mean trait values ± SD are shown. The significance of the difference in incidence was determined by Chi-square test and the significance of the difference in EAE-quantitative trait variables was determined using the Mann-Whitney test.

| WT | H4RKO | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 31/32 | 30/30 | |

| Mean day of onset | 16.25 ± 3.74 | 13.63 ± 2.74 | 0.004 |

| Cumulative score | 36.00 ± 18.3 | 56.03 ± 20.72 | 0.0002 |

| Day affected | 14.00 ± 6.3 | 17.40 ± 2.77 | 0.002 |

| Severity index | 2.42 ± 0.88 | 3.21 ± 1.02 | 0.004 |

| Peak score | 3.37 ± 1.26 | 4.33 ± 0.84 | 0.001 |

As an additional quantitative measure of differences in the neuroinflammatory response, we examined BBB permeability at d8, d10, d12, and d14 post-immunization. Compared to WT mice, the increase in BBB permeability during the early acute phase of the disease was significantly greater in H4RKO mice (Figure 1C). Taken together, these data show that H4R signaling negatively regulates EAE severity.

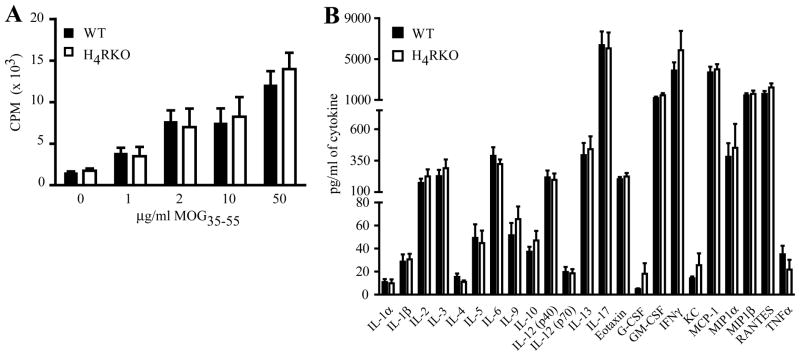

WT and H4RKO ex vivo CD4+ TE cell responses are comparable

Although the precise pathogenic mechanism of EAE and MS is unknown, it is believed to be mediated by CD4+ T cell-dependent activities (26). H4R is expressed by T cells (15) and has been implicated in immune regulatory functions (15, 20, 21). Therefore, to delineate the immune mechanism underlying increased EAE severity of H4RKO mice, the MOG35-55 specific T cell responses were compared on d10 post immunization. No significant differences in T cell proliferation (Figure 2A) or cytokine/chemokine production (Figure 2B) in response to MOG35-55 re-stimulation were detected between H4RKO and WT splenic and draining lymph node (DLN) cells.

Figure 2. Ex vivo Ag-specific T cell proliferation and cytokine/chemokines profiles of MOG35-55-CFA-PTX-immunized WT and H4RKO mice.

(A) Ag-specific T cell proliferative responses were evaluated by [3H]-thymidine incorporation (n=6 per strain). Mean cpm ± SD were calculated from triplicate wells. The significance of differences was calculated by Two-Way Analysis of Variance. (B) Protein production by MOG35-55-stimulated splenocytes from WT and H4RKO mice. Spleen and DLN cells from d10-immunized mice were stimulated with MOG35-55 for 72h and culture supernatants were analyzed for protein levels by Bio-Plex. Cytokine production in the absence of MOG35-55 was below detection limits. Significance of differences in T cell proliferation or cytokine production was determined using Mann-Whitney test, and Bonferroni’s corrected p-value for multiple comparisons.

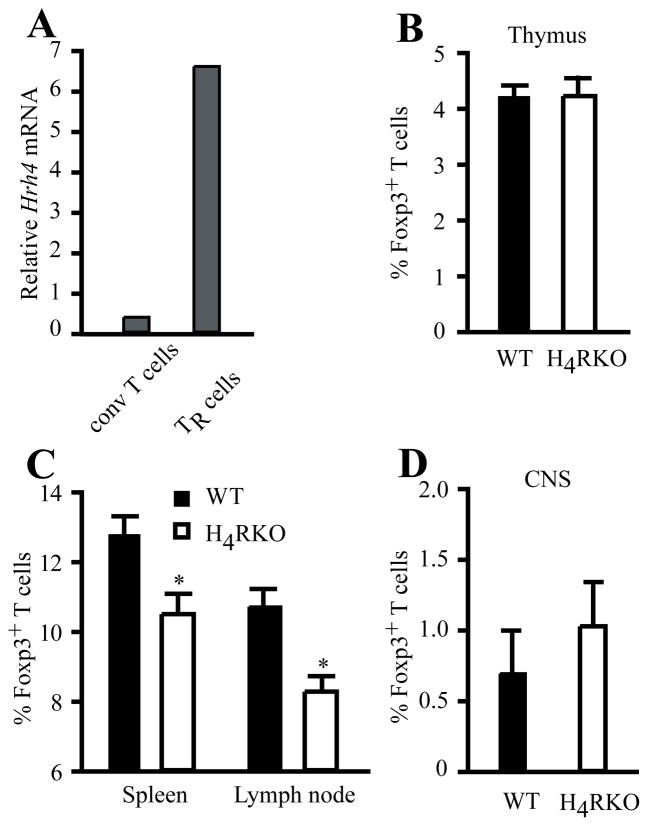

H4R influences the frequency of TR cells in secondary lymphoid organs

Foxp3+ TR cells play a fundamental role in controlling inflammatory responses and preventing autoimmune diseases, including EAE (27, 28), and mast cells and HA have been implicated in controlling peripheral tolerance via TR cells (29, 30). In addition, the H4R agonist 4-mHA induces recruitment of TR cells into the lung and inhibits development of allergic asthma (23). Although H4R expression has been reported in T cells, it is unknown if it is expressed by TR cells. We therefore compared the Hrh4 mRNA levels between CD4+CD25−Foxp3− conventional T cells and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ TR cells from naïve C57BL/6J mice. As shown in Figure 3A, Hrh4 mRNA levels were higher in TR cells compared to conventional CD4+ T cells. Given this elevated expression of Hrh4 in TR cells and the importance of these cells in controlling inflammatory and autoimmune responses, we hypothesized that the deficiency of H4R may affect TR cell development and/or frequency. Therefore, we compared the proportion of Foxp3+ TR cells in the thymus of naïve WT and H4RKO mice and found no difference among the single positive CD4 thymocytes (Figure 3B). However, the proportion and the absolute number of TR cells in spleen and LN were significantly lower in H4RKO mice compared to WT mice (Figure 3C and Suppl. Fig. 1A). Next, we examined the proportion of the CNS-resident TR cells in naïve WT and H4RKO mice and, in contrast to the periphery, no detectable difference was observed (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Analysis of Foxp3+ T cell frequency in lymphoid tissues of naïve WT and H4RKO mice.

(A) mRNA expression of Hrh4 was measured from sorted naïve CD4+CD25+ T cells (TR cells) and compared to conventional CD4+CD25− T cells (conv T cells). Expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR and analyzed using comparative Ct method with β2-microglobulin as an endogenous control. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B–C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD4+CD8−TCRβ+Foxp3+ TR cell frequency in thymus (B), spleen and LN (C), and CNS (D) of naive WT and H4RKO mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann-Whitney test (*p<0.05). Flow cytometric data represent the mean ± SEM of 8 individual mice (B and C), or 3 experiments (pool of 5 mice per experiment) (D).

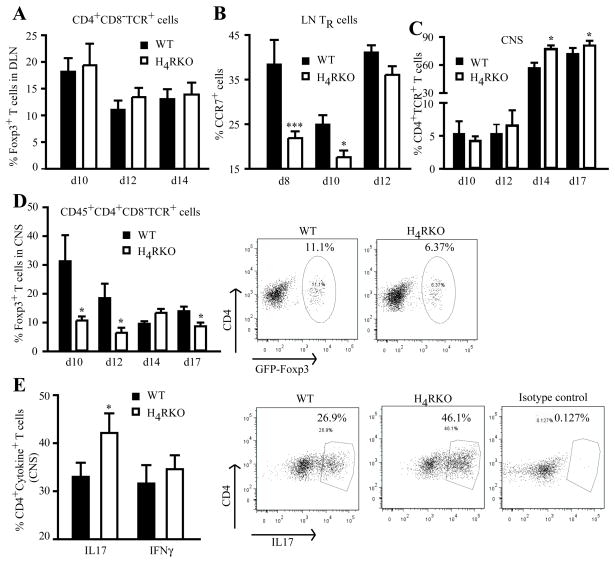

H4R controls TR cell infiltration and inflammation in the CNS during acute EAE

Because H4RKO mice have a lower frequency of TR cells in secondary lymphoid organs compared with WT mice, we reasoned that the increased disease severity in H4RKO mice may be due to a paucity of CNS-TR cells during the induction- and/or acute effector-phase of the disease. Therefore, the frequency of TR cells was determined in WT and H4RKO mice following immunization. DLN cells and CNS-associated infiltrating mononuclear (MN) cells were isolated at different times after immunization, and the frequency of TR cells among the CD4+TCR+ T cells analyzed. On d10 post-immunization, the proportion of TR cells in the DLN comprised ~20% of the CD4+TCR+ T cells, representing an increase of ~2-fold over naïve mice. On d12 and d14 the proportion of TR cells dropped to ~10–12% of the T cells. However, no significant difference in the proportion of TR cells or TE cells in the DLN was detectable between WT and H4RKO mice at any of the time points examined (Figure 4A and Suppl. Fig. 2). We then evaluated the expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7, which has been shown to be involved in the recruitment and interaction of TR cells with mature DC in the paracortical area of the LN (31). H4RKO mice have a lower proportion of TR cells expressing CCR7 at d8 and d10 after immunization when compared to WT mice, with no differences by d12 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Reduced frequency of Foxp3+ TR cell and increased Th17 cells in the CNS of immunized H4RKO mice.

Flow cytometric analysis of the frequency of CD4+CD8−TCRβ+Foxp3+ TR cell in DLN and spleen (A) and percentage of TR cells expressing CCR7 (B), and percentage of TR cells (D) or Th17 (E) in CNS-infiltrating MN cells of immunized WT and H4RKO mice. (C) Percentage of total CD4+TCR+ T cells infiltrating the CNS of immunized mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann-Whitney test (*p<0.05). Flow cytometric data represent the mean ± SEM of 5–8 individual mice (at each time point).

By d10 post-immunization, we observed robust recruitment of TR cells into the CNS of both WT and H4RKO mice compared to naïve controls (Figure 3D vs. Figure 4D). In contrast to the DLN of immunized mice, the frequency of TR cells in the CNS of H4RKO mice was lower than that detected in WT mice at d10, d12, and d17 post-immunization (Figure 4D). Consistent with the lower proportion of TR cells in the CNS of H4RKO mice, a decrease in the absolute number of TR cells was also observed (Suppl. Fig. 1B). A role for histamine in regulating the adhesion and recruitment of immune cells has been suggested previously (32). Therefore, since TR cells have been reported to express greater levels of ICAM-1/CD45 and P-selectin in comparison with non-TR cells (33), and CCR6 expression has been shown to regulate EAE pathogenesis by controlling TR cell recruitment to the CNS (33), we evaluated the expression levels of these in CNS infiltrating TR cells of WT and H4RKO mice. No differences in the expression levels of these molecules were detected between WT and H4RKO CNS-infiltrating MN cells during EAE (data not shown). We also determined whether there was any difference in the overall infiltration of CD4+ T cells into the CNS after immunization. As expected, the proportion of TCR+CD4+ T cells increased with disease progression, and by d14 post-immunization the CNS of H4RKO mice exhibited a significantly greater proportion of these cells compared to WT mice (Figure 4C).

Th1 and Th17 cells have been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of EAE, and TR cells inhibit the induction of these pathogenic cells (26). Therefore, we compared autoreactive effector CD4 responses in the target organ of WT and H4RKO mice during EAE by examining the frequency of encephalitogenic IFNγ– and IL17-producing Th1 and Th17 cells in the CNS. The frequency of Th17 cells in H4RKO mice was higher than that of WT mice, whereas the frequency of Th1 cells was comparable between the two strains (Figure 4E).

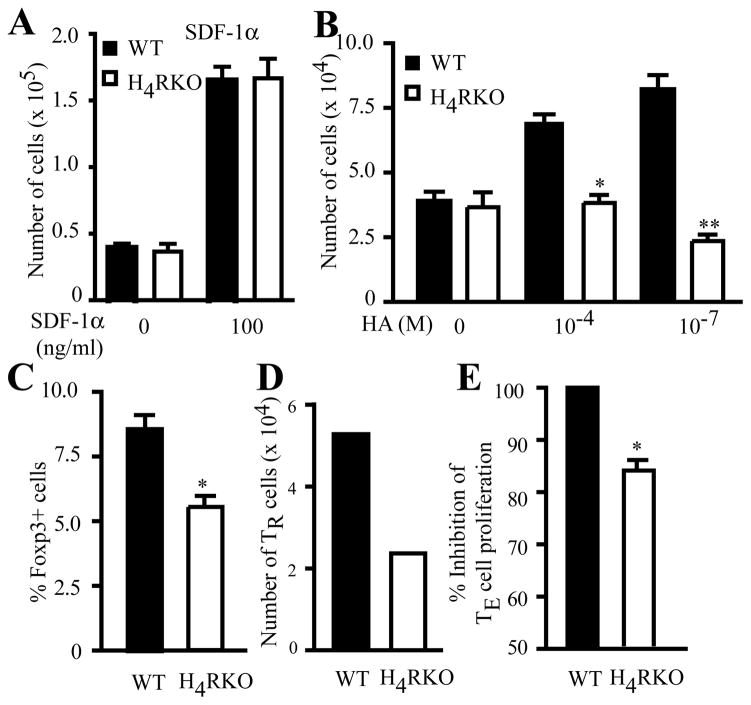

H4R regulates TR cell chemotaxis and suppressor functions

It has been shown that the H4R agonist 4-mHA reduces airway hyperreactivity and inflammation, and that this effect is associated with the recruitment of TR cells into the lung (23). Additionally, H4R signaling is involved in the migration of DC and mast cells to sites of inflammation (15, 19, 21). We have shown that increased EAE severity in H4RKO mice correlates with decreased numbers of infiltrating TR cells into the CNS during the acute phase of disease (Figure 4D and Suppl. Fig. 1B), consistent with the requirement for TR cells in the target tissue for adequate immune regulation (34). Because we observed differences in the number of TR cells in the CNS between immunized WT and H4RKO mice, we examined whether H4R is required for optimal CD4+ T cell chemotaxis. We performed in vitro migration assays using purified CD4+ T cells from immunized WT and H4RKO mice. WT and H4RKO CD4+ T cells responded equally to stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a known strong chemotactic factor for leukocytes (Figure 5A). However, WT CD4+ T cells responded to HA-induced migratory signals, whereas H4RKO CD4+ T cells did not (Figure 5B). These results suggest that HA, acting through H4R, functions as a chemotactic factor for T cells.

Figure 5. H4R positively regulates TR cell chemotaxis and suppressive activity.

Total CD4+ T cells (A–C) or sorted TR cells (D) from d10 immunized WT (black bars) and H4RKO (white bars) mice were subjected to migration assay using either 100 ng/ml SDF-1α(A) or 10−4 M and 10−7HA (B). (C) Migrated cells were stained for identification of Foxp3+ TR cells and % of TR cells from the total migrating cells is shown. (E) WT- or H4RKO-CD4+GFP−Foxp3− responder cells were cultured with WT irradiated spleen cells and co-cultured at 0.5:1 (TR:TE) ratio with WT- or H4RKO-CD4+GFP+Foxp3+ TR cells, respectively. Significance of differences was calculated using Mann-Whitney test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01). (A) and (B) are the average of 3 independent experiments. (D) is representative of 2 independent experiments. (E) is the average of 3 independent experiments.

Interestingly, when the proportion of Foxp3+ TR cells within the total T-cell population that migrated in response to HA was analyzed, the cells from WT mice contained a significantly greater proportion of Foxp3+ TR cells compared to those from H4RKO mice (Figure 5C). To test the H4R-dependent chemotactic activity directly in TR cells, we utilized WT- and H4RKO-Foxp3gfp knockin (KI) mice, sorted GFP+ TR cells from immunized mice and assessed the chemotactic response to HA. As with total CD4+ T cells, the H4RKO Foxp3+ TR cells had an impaired migratory response to HA (Figure 5D). Furthermore, we tested whether TR cells from WT and H4RKO mice exhibited differences in their in vitro suppressive function and found that d10 H4R-deficient TR cells have decreased ability to suppress anti-CD3 + APC-induced proliferation of CD4+ T cells compared to WT TR cells (Figure 5E). Importantly, compared to H4RKO mice, the DLNs of WT mice contained significantly greater numbers of IL10+ T cells. However, no difference in the number of IL10+ cells infiltrating the CNS was seen between WT and H4RKO mice (Suppl. Fig. 3). These data suggest that intrinsic H4R signaling regulates TR cell chemotaxis and suppressor activities, the absence of which leads to exacerbation of EAE in H4RKO mice.

Discussion

Histamine and its receptors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the CNS such as MS and its autoimmune model EAE (35). To date, H1R, H2R and H3R have been shown to modulate susceptibility to EAE (11, 12, 36). The most recently characterized HR, H4R, is mainly expressed on hematopoietic cells (15) and it is postulated to have an immunomodulatory function during inflammatory and allergic conditions (15, 20, 21). The role of H4R in EAE, however, has not been studied. We show that the H4R negatively regulates the severity of MOG35-55-induced EAE, since mice lacking this receptor exhibit an exacerbated disease and immunopathology, as well as an increase in BBB permeability during the early acute phase of the disease. Our results are consistent with the studies on airway inflammation in which H4R signaling modulates the anti-inflammatory response (23). Furthermore, we show that H4R controls the frequency of TR cells in secondary lymphoid tissues, as well as their chemotaxis and suppressive activities, and deficiency of this receptor leads to a reduction in the proportion of TR cells in the CNS during the acute effector phase of disease and impairment of an anti-inflammatory response, leading to an increase in the proportion of encephalitogenic Th17 cells.

We found that H4R is highly expressed on TR cells, which play an essential role in controlling autoimmune diseases, including EAE (28, 37). We show here that H4R signaling has a significant impact on regulating the proportion and distribution of natural TR cells in secondary lymphoid organs but not on their thymic development. These results support the concept that specific factors in the microenvironment of peripheral lymphoid tissues may dictate the fate of the immune response by influencing TR cell biology (i.e., the frequency and distribution of TR) (38, 39). Naïve H4RKO mice have lower frequency of peripheral TR cells than WT mice and, upon MOG35-55 immunization, exhibit more severe EAE. Given this result, peripheral activation/expansion of Ag-specific autoreactive T cells may be ineffectively controlled by the limited number of peripheral TR cells present in naïve H4RKO mice. Despite the observed differences in TR numbers of naïve H4RKO and WT mice, similar levels of peripheral TE and TR cells were detected in WT and H4RKO mice during the acute phase of the disease. However, when we evaluated the in vitro capacity of TR cells to inhibit the TE cell proliferative response, d10 H4RKO TR cells were less potent than d10 WT TR cells. Importantly, during disease progression, H4RKO mice had fewer IL10-producing T cells in the DLN, but not in the CNS. Taken together, these data indicate that the H4R not only affects the frequency and/or localization of LN TR cells but also influences their function. However, the lack of H4R does not affect the numbers of induced TR cells in periphery, which rules this out as a potential mechanism underlying the differences in severity to EAE between WT and H4RKO mice. It is also possible that H4R signaling influences the potency of the encephalitogenic T cell response and/or refractoriness to TR cell suppression.

Our results show that immunized H4RKO mice have a higher proportion of inflammatory Th17 cells within the CNS, consistent with fewer TR cells infiltrating the CNS, despite the fact that no difference in CNS-resident TR cells was observed between naïve WT and H4RKO mice. These data may be explained by at least two mechanisms: a defect in the proliferation/expansion of TR cells, or a deficit in the migratory capacity of these cells to enter the CNS. Since we observed a robust expansion of peripheral induced TR cells during the effector phase of disease with no differences between WT and H4RKO mice, a defect in TR cell responsiveness is unlikely to be involved. We therefore hypothesize that a defect in migration may explain the reduced number of TR cells in the CNS of immunized H4RKO mice. Indeed, the pharmacological activation of H4R with the agonist 4-mHA has been shown to influence TR recruitment into the lung (23). Our current findings, using a genetic approach, further demonstrate that HA signals through the H4R to induce migration of TR cells.

In addition to our observation that there is a defect in migration/trafficking of TR cells in immunized H4RKO mice, we found that the proportion of peripheral TR cells expressing the LN homing receptor CCR7 was decreased in H4RKO compared to WT mice, on d8 and d10 post-immunization, but reached comparable levels by d12. This may have contributed to differences in disease severity, since one of the functions of this chemokine receptor is to promote the recruitment and interaction of TR cells with mature DCs to ultimately regulate the TE cell-immune response (31, 40). Indeed, in vivo studies show that CD62L+CCR7+ TR cells delay adoptive transfer of diabetes (41). However, future studies will address whether CCR7 expression in TR cells is directly regulated by H4R signaling in our model. Additionally, the lack of H4R may alter the ability of the other HRs to elicit migratory responses, i.e. through receptor desensitization.

Taken together, our results suggest that H4R signaling, either directly or indirectly: 1) regulates the proportion of peripheral TR cells, providing a checkpoint to regulate Ag-specific TE expansion in the periphery, and 2) increases the proportion of TR cells in the target tissue before the expansion and/or recruitment of encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells into the CNS before the onset of EAE.

It has recently been shown that H4R is functionally expressed in the CNS (42, 43); hence we cannot exclude the possibility that the absence of H4R signaling also contributes to increased disease severity as a function of disrupted CNS-central functions. Our current findings suggest that H4R signaling negatively regulates EAE by controlling the infiltration and suppressive activity of TR cells within the CNS during the early acute effector phase of the disease, a critical time point in regulating the proliferation and expansion of autoreactive pathogenic T cells (26). Our observation that H4RKO mice develop more severe EAE than WT mice highlights the importance of the temporal localization of TR cells in the relevant tissue for controlling the inflammatory response. Moreover, our findings suggest that the use of both peripheral and central acting H4R agonists may be useful in treating patients with clinically isolated syndrome, at the onset of MS, or upon relapse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants AI041747, NS036526, and NS060901.

We thank Drs. Mercedes Rincon, Laure Case and Sean A. Diehl for helpful discussions, the staff at the University of Vermont DNA Sequencing Facility for assistance with qRT-PCR, Colette Charland for cell sorting, and Dr. Janice Y. Bunn for statistical analysis.

Abbreviations used

- HA

histamine

- 4-mHA

4-methylHA

- EAE

experimental allergic encephalomyelitis

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- Hrh/HR

histamine receptor

- WT

wild type

- MOG35-55

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35–55

- TR

T regulatory cell

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- TE

T effector cell

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- LN

lymph node

- DLN

draining LN

- MN

mononuclear cells

- KI

knockin

Footnotes

Author contributions: R.dR., R.N., and C.T. designed research; R.dR., R.N., N.S., M.E.P., and J.F.Z. performed research; R.dR., R.N., E.W., R.L.T., and C.T. analyzed data; and R.dR., R.N., and C.T. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Akdis CA, Simons FE. Histamine receptors are hot in immunopharmacology. European journal of pharmacology. 2006;533:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jutel M, Blaser K, Akdis CA. Histamine receptors in immune regulation and allergen-specific immunotherapy. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2006;26:245–259. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott NJ. Inflammatory mediators and modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2000;20:131–147. doi: 10.1023/a:1007074420772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebo BF, Jr, Yong T, Orr EL, Linthicum DS. Hypothesis: a possible role for mast cells and their inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of neuroscience research. 1996;45:340–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960815)45:4<340::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuomisto L, Kilpelainen H, Riekkinen P. Histamine and histamine-N-methyltransferase in the CSF of patients with multiple sclerosis. Agents and actions. 1983;13:255–257. doi: 10.1007/BF01967346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orr EL, Stanley NC. Brain and spinal cord levels of histamine in Lewis rats with acute experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of neurochemistry. 1989;53:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, Klonowski P, Austin A, Lad N, Kaminski N, Galli SJ, Oksenberg JR, Raine CS, Heller R, Steinman L. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature medicine. 2002;8:500–508. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso A, Jick SS, Hernan MA. Allergy, histamine 1 receptor blockers, and the risk of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2006;66:572–575. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000198507.13597.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logothetis L, I, Mylonas A, Baloyannis S, Pashalidou M, Orologas A, Zafeiropoulos A, Kosta V, Theoharides TC. A pilot, open label, clinical trial using hydroxyzine in multiple sclerosis. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 2005;18:771–778. doi: 10.1177/039463200501800421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedotti R, DeVoss JJ, Youssef S, Mitchell D, Wedemeyer J, Madanat R, Garren H, Fontoura P, Tsai M, Galli SJ, Sobel RA, Steinman L. Multiple elements of the allergic arm of the immune response modulate autoimmune demyelination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:1867–1872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252777399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma RZ, Gao J, Meeker ND, Fillmore PD, Tung KS, Watanabe T, Zachary JF, Offner H, Blankenhorn EP, Teuscher C. Identification of Bphs, an autoimmune disease locus, as histamine receptor H1. Science. 2002;297:620–623. doi: 10.1126/science.1072810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teuscher C, Poynter ME, Offner H, Zamora A, Watanabe T, Fillmore PD, Zachary JF, Blankenhorn EP. Attenuation of Th1 effector cell responses and susceptibility to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in histamine H2 receptor knockout mice is due to dysregulation of cytokine production by antigen-presenting cells. The American journal of pathology. 2004;164:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63176-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musio S, Gallo B, Scabeni S, Lapilla M, Poliani PL, Matarese G, Ohtsu H, Galli SJ, Mantegazza R, Steinman L, Pedotti R. A key regulatory role for histamine in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: disease exacerbation in histidine decarboxylase-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:17–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noubade R, Milligan G, Zachary JF, Blankenhorn EP, del Rio R, Rincon M, Teuscher C. Histamine receptor H1 is required for TCR-mediated p38 MAPK activation and optimal IFN-gamma production in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:3507–3518. doi: 10.1172/JCI32792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zampeli E, Tiligada E. The role of histamine H4 receptor in immune and inflammatory disorders. British journal of pharmacology. 2009;157:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, Ma X, Jiang X, Wilson SJ, Hofstra CL, Blevitt J, Pyati J, Li X, Chai W, Carruthers N, Lovenberg TW. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of a fourth histamine receptor (H(4)) expressed in bone marrow. Molecular pharmacology. 2001;59:420–426. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosethorne EM, Charlton SJ. Agonist-biased signalling at the histamine H4 receptor: JNJ7777120 recruits beta-arrestin without activating G proteins. Molecular pharmacology. 2011 doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai P, Thurmond RL. Histamine H4 Receptor Activation Enhances LPS-induced IL-6 Production in Mast Cells via ERK and PI3K Activation. European journal of immunology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/eji.201040932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider E, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Arock M, Dy M. Trends in histamine research: new functions during immune responses and hematopoiesis. Trends in immunology. 2002;23:255–263. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofstra CL, Desai PJ, Thurmond RL, Fung-Leung WP. Histamine H4 receptor mediates chemotaxis and calcium mobilization of mast cells. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2003;305:1212–1221. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurmond RL, Gelfand EW, Dunford PJ. The role of histamine H1 and H4 receptors in allergic inflammation: the search for new antihistamines. Nature reviews. 2008;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrd2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gschwandtner M, Rossbach K, Dijkstra D, Baumer W, Kietzmann M, Stark H, Werfel T, Gutzmer R. Murine and human Langerhans cells express a functional histamine H4 receptor: modulation of cell migration and function. Allergy. 2010;65:840–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan RK, McAllister B, Cross L, Green DS, Kornfeld H, Center DM, Cruikshank WW. Histamine 4 receptor activation induces recruitment of FoxP3+ T cells and inhibits allergic asthma in a murine model. J Immunol. 2007;178:8081–8089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu B, Shao Y, Zhang J, Dong XL, Liu WL, Yang H, Liu L, Li MH, Yue CF, Fang ZY, Zhang C, Hu XP, Chen BC, Wu Q, Chen YW, Zhang W, Wan J. Polymorphisms in human histamine receptor H4 gene are associated with atopic dermatitis. The British journal of dermatology. 2010;162:1038–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu B, Shao Y, Li P, Zhang J, Zhong Q, Yang H, Hu X, Chen B, Peng X, Wu Q, Chen Y, Guan M, Wan J, Zhang W. Copy number variations of the human histamine H4 receptor gene are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. The British journal of dermatology. 2010;163:935–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:393–407. doi: 10.1038/nri2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor RA, Anderton SM. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the control of experimental CNS autoimmune disease. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2008;193:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forward NA, Furlong SJ, Yang Y, Lin TJ, Hoskin DW. Mast cells down-regulate CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cell suppressor function via histamine H1 receptor interaction. J Immunol. 2009;183:3014–3022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu LF, Lind EF, Gondek DC, Bennett KA, Gleeson MW, Pino-Lagos K, Scott ZA, Coyle AJ, Reed JL, Van Snick J, Strom TB, Zheng XX, Noelle RJ. Mast cells are essential intermediaries in regulatory T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2006;442:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ueha S, Yoneyama H, Hontsu S, Kurachi M, Kitabatake M, Abe J, Yoshie O, Shibayama S, Sugiyama T, Matsushima K. CCR7 mediates the migration of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells to the paracortical areas of peripheral lymph nodes through high endothelial venules. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2007;82:1230–1238. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lapilla M, Gallo B, Martinello M, Procaccini C, Costanza M, Musio S, Rossi B, Angiari S, Farina C, Steinman L, Matarese G, Constantin G, Pedotti R. Histamine regulates autoreactive T cell activation and adhesiveness in inflamed brain microcirculation. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2011;89:259–267. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0910486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohm AP, Miller SD. Role of ICAM-1 and P-selectin expression in the development and effector function of CD4+CD25+regulatory T cells. Journal of autoimmunity. 2003;21:261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huehn J, Hamann A. Homing to suppress: address codes for Treg migration. Trends in immunology. 2005;26:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jadidi-Niaragh F, Mirshafiey A. Histamine and histamine receptors in pathogenesis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teuscher C, Subramanian M, Noubade R, Gao JF, Offner H, Zachary JF, Blankenhorn EP. Central histamine H3 receptor signaling negatively regulates susceptibility to autoimmune inflammatory disease of the CNS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:10146–10151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702291104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venken K, Hellings N, Liblau R, Stinissen P. Disturbed regulatory T cell homeostasis in multiple sclerosis. Trends in molecular medicine. 2010;16:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.del Rio R, Sun Y, Alard P, Tung KS, Teuscher C. H2 control of natural T regulatory cell frequency in the lymph node correlates with susceptibility to day 3 thymectomy-induced autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2011;186:382–389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wheeler KM, Samy ET, Tung KS. Cutting edge: normal regional lymph node enrichment of antigen-specific regulatory T cells with autoimmune disease-suppressive capacity. J Immunol. 2009;183:7635–7638. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider MA, Meingassner JG, Lipp M, Moore HD, Rot A. CCR7 is required for the in vivo function of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:735–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szanya V, Ermann J, Taylor C, Holness C, Fathman CG. The subpopulation of CD4+CD25+ splenocytes that delays adoptive transfer of diabetes expresses L-selectin and high levels of CCR7. J Immunol. 2002;169:2461–2465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connelly WM, Shenton FC, Lethbridge N, Leurs R, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Lees G, Chazot PL. The histamine H4 receptor is functionally expressed on neurons in the mammalian CNS. British journal of pharmacology. 2009;157:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strakhova MI, Nikkel AL, Manelli AM, Hsieh GC, Esbenshade TA, Brioni JD, Bitner RS. Localization of histamine H4 receptors in the central nervous system of human and rat. Brain research. 2009;1250:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.