Abstract

Objectives

Acute laboratory stressors elicit elevations in serum levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Chronic stressors, such as family dementia caregiving, promote a state of chronic low-grade elevation in circulating inflammatory markers. The recurrent daily stressors associated with chronic stress may lead to repeated and sustained activation of the physiological stress systems. The present study evaluated the possibility that greater exposure and reactivity to daily stressors fueled increased levels of circulating inflammatory markers among family dementia caregivers, compared to noncaregiving controls.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 53 caregivers and 77 noncaregiving controls. A semi-structured interview assessed the occurrence of daily stressors in the past 24 hours. A blood sample provided data on two inflammatory markers, CRP and IL-6.

Results

Caregivers were more likely to experience multiple stressors in the past 24 hours than noncaregiving controls. The occurrence of multiple daily stressors was associated with greater serum IL-6 and CRP levels. The greater occurrence of daily stressors in the past 24 hours partially mediated the relationship between dementia caregiving and CRP levels.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the cumulative effect of daily stressors promotes elevations in inflammatory markers. Greater exposure to daily stressors may be a psychobiological mechanism leading to elevations in CRP levels among family dementia caregivers.

Keywords: daily stress, chronic stress, inflammation, caregiving

The chronic stress of caregiving for a loved one with dementia has been associated with a state of immune dysregulation evidenced by weakened control over the expression of latent herpes viruses, impaired wound healing, poorer responses to vaccines, and a state of chronic low-grade elevations in circulating inflammatory markers (Gouin, Hantsoo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2008). Elevations in systemic IL-6 and CRP levels have been related to greater incidence of depression, cardiovascular disorder, diabetes, certain cancers, autoimmune diseases, frailty, and mortality (Maggio, Guralnik, Longo, & Ferrucci, 2006), providing a plausible physiological pathway via which chronic stress may lead to poor health.

Acute laboratory stressors lead to transient increases in circulating IL-1β, IL-6, and CRP (Steptoe, Hamer, & Chida, 2007). Stress-induced elevations in IL-6 have been observed up to 22 hours following exposure to laboratory social stressor (Kiecolt-Glaser, et al., 2005). Furthermore, in a daily diary study greater interpersonal stress during a 2-week period was related to higher CRP (Fuligni, et al., 2009), suggesting that recent stressors can impact circulating inflammatory markers.

Family dementia caregivers experience numerous daily stressors. These daily hassles can lead to repeated and sustained activation of the stress system. The occurrence of recurring daily stressors may then fuel chronic or sustained elevations in circulating markers of inflammation.

Two main models can explain the relationship between daily and chronic stressors (Almeida, 2005). The exposure model suggests that the experience of a large number of daily stressors has a cumulative, detrimental impact on health. The reactivity model stipulates that chronic stress impacts health by increasing psychological and physiological reactivity to daily events.

The goals of this study were to investigate whether greater exposure and reactivity to daily stressors may fuel overproduction of inflammatory biomarkers among family dementia caregivers. The hypotheses were 1) caregivers will report more daily stressors than controls; 2) the number of daily stressors will be associated with IL-6 and CRP; 3) caregivers will display a stronger association between daily stressors and IL-6 and CRP levels than controls.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study on stress and health. Inclusion criteria were caring for a spouse or a parent with dementia, and spending at least 5 hours per week in caring duties. Noncaregiving control participants were excluded from the study if they were involved in any caregiving activity in the past year. Participants aged 45–90 with a body mass index (BMI) less than 40 were included in the study. Individuals with immune-related diseases (e.g. acute infection, diabetes, recent cancer, rheumatoid arthritis) or using immune-related medication were excluded from the study (e.g., statins, antibiotics).

Protocol

In this cross-sectional study, laboratory or home visits were scheduled between 8 to 10 AM to minimize the impact of diurnal changes in circulating cytokines. After signing the consent form, the participants had their blood drawn and body measurements taken. Subsequently, participants filled out self-reported questionnaires and completed a semi-structured interview.

Measures

Self-reported questionnaires

Smoking, and alcohol use in the past week were evaluated using a standard questionnaire. The Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors Questionnaires (CHAMPS) provided an estimate of the weekly caloric expenditure in physical activity (Stewart, et al., 2001). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) assessed sleep quality and sleep disturbances in the past month (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). The Older Adult Resources and Services (OARS) Multidimensional functional Assessment Questionnaire evaluated the frequency of chronic medical conditions and medication use (Fillenbaum & Smyer, 1981). The Center for Epidemiological Scale-Depression (CES-D) assessed depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). The Bless Dementia Scale (BDS) evaluated the severity of the dementia symptoms as perceived by the caregiver (Erkinjuntti, Hokkanen, Sulkava, & Palo, 1988).

Semi-structured interview

The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE) assessed the occurrence of daily stressors in the past 24 hours (Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002). This instrument was chosen because of its flexibility and sensitivity in the assessment of idiosyncratic daily stressors such as the ones experienced by family dementia caregivers.

IL-6 and CRP assays

Serum IL-6 levels were determined using Quantikine High Sensitivity Immunoassay kits (R&D). Samples were run undiluted in duplicate. Sensitivity of the IL-6 kit was 0.039 pg/mL. Intra-assay coefficient of variation had a range of 6.9–7.8% and inter-assay coefficient variation had a range of 6.5–9.6% 7.3%. Data for 10 caregivers and 10 controls were lost because of technical problems with the assay. The high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) assay was performed using chemiluminescence methodology with the Immulite 1000 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Los Angeles, Ca.). The lowest level of detection was 0.3 mg/dL. Intra-assay coefficient of variation was 5.1% and inter-assay coefficient variation was 7.3%.

Statistical analyses

The DISE data were coded as a three-level categorical variable distinguishing the absence of stressors, presence of one stressor, or occurrence of multiple stressors. Base 10 logarithmic transformations were applied to variables with a skewed distribution. Chi-square and analysis of variance tests assessed group differences between caregivers and noncaregiving controls. A multinomial logistic regression model evaluated group differences in the report of daily stressors. Hierarchical linear regression models were fitted with daily stressors and caregiving status as independent variables, and IL-6 and CRP as dependent variables. The caregiving status by daily stressors interaction tested the moderating effect of group membership. As recommended by Preacher & Hayes (2004), the mediation effect was tested by showing that the indirect effect of the independent variable (caregiving status) on the dependent variable (CRP) through the mediator (daily stressors) was significantly different from zero. A structural equation modeling approach using a parametric bootstrapping resampling procedure was used to test the significance of the indirect effect. The covariates included in all models with IL-6 or CRP as dependent variables were gender, age, education, BMI, ethnicity and marital status. A two-sided .05 alpha level was used for the study.

Results

The final sample comprised 53 caregivers and 77 noncaregiving controls. Caregivers and controls did not significantly differ in age (M=64.30, SD =11.17 vs. M=95.97, SD= 14.35, p = .48), in the proportion of females (79.25% vs. 84.41%, p = .45), Caucasians (79.25% vs. 84.41%, p =.45), currently employed individuals (45.28% vs. 49.35%, p = .65), and college graduates (69.81% vs. 67.53%, p = .91). However, caregivers were significantly more likely to be married than noncaregiving controls (75.48% vs. 35.06%, p = .001).

Caregiving status and occurrence of stressors in the past 24 hours

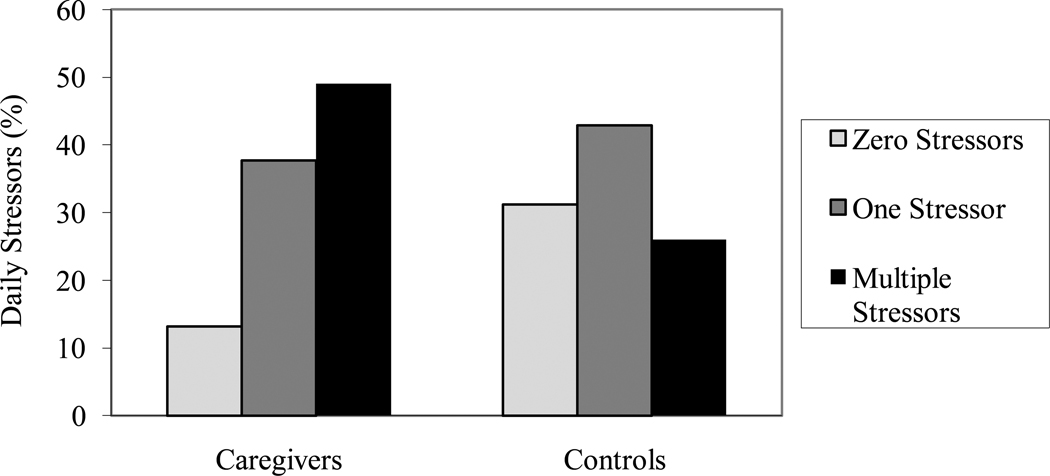

Study participants reported between 0 and 6 stressors in the past 24 hours. A multinomial logistic regression model including age, sex, employment status, and marital status as covariates revealed that caregiving status was significantly related to the report of multiple stressors in the past 24 hours, χ2(1) = 7.43, p = .006, as compared to the absence of a stressor. However, caregivers were no more likely than controls to experience one stressor in the past 24 hours, χ2(1) = 2.31, p = .12 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of stressors in the past 24 hours as a function of caregiving status.

Caregiving status, daily stressors and IL-6 and CRP production

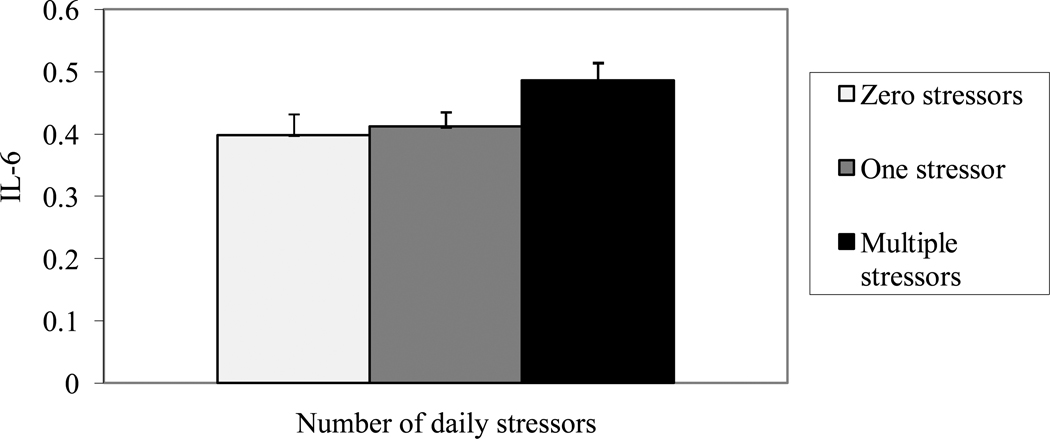

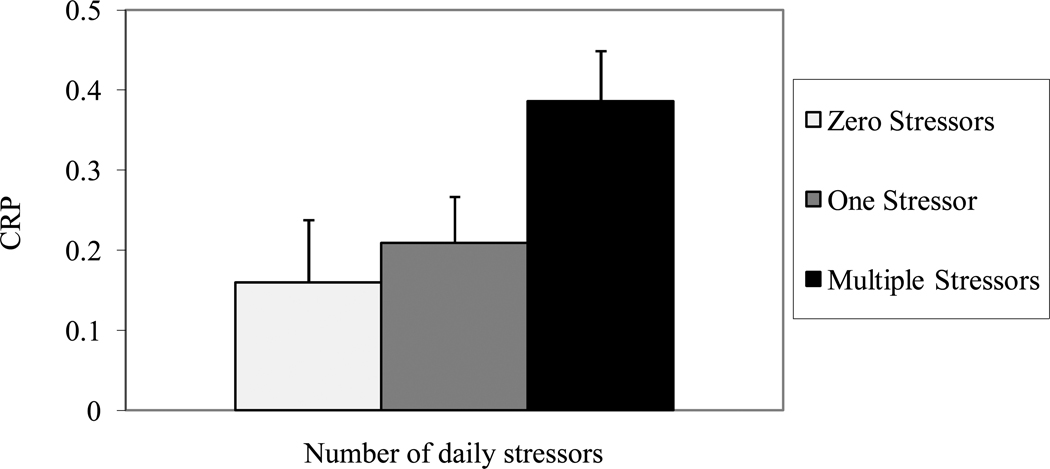

Caregiving status was not significantly related to IL-6 levels, β = .01, t(108) = .25, p = .80, R2 = .001, but caregivers had significantly higher CRP values than noncaregiving controls, β = .19, t(128) = 2.23, p = .03, R2 = .037. After adjusting for caregiving status, daily stressors were related to IL-6, β= .05, t(109) = 2.06, p = .04, R2 = .034, and CRP, β= .9, t(129) = 2.14, p = .04, R2 = .036. Post-hoc tests with Tukey-Kramer adjustment revealed that individuals who experienced multiple stressors in the past 24 hours had higher IL-6 levels, t(101) = 2.02, p = .04, and CRP, t(121) = 2.02, p = .04, than participants who reported no stressors, and marginally greater IL-6, t(101) = 1.84, p = .07, and greater CRP, t(121) = 2.02, p = .04, than individuals reporting one stressor. However, IL-6, t(101) = .16, p = .87, and CRP, t(121) = 1.21, p = .23, values did not differ among participants who experienced zero or one stressors (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Log10 Interleukin-6 (pg/ml) serum levels as a function of the number of stressors in the past 24 hours. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Figure 3.

Log10 C-reactive protein (mg/L) serum levels as a function of the number of stressors in the past 24 hours. Error bars represent standard errors of mean.

Exposure and reactivity models

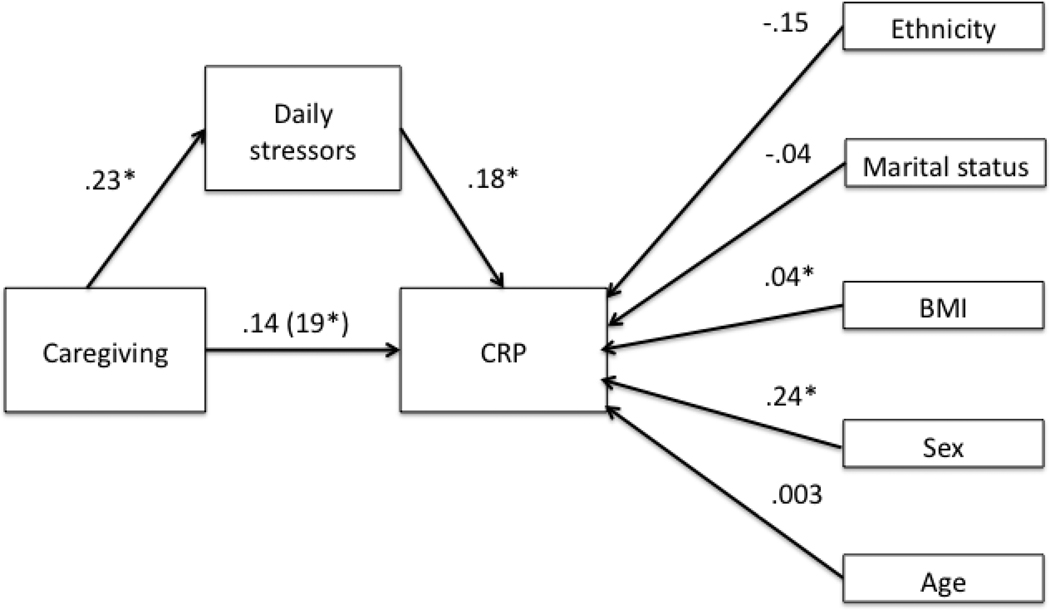

A structural equation model tested the indirect effect of daily stressors on the relationship between caregiving status and CRP levels (Figure 4). Both the CFI = 1.00 and the RMSEA = .08 [.04–.12] indicated that the model fit the data well. Furthermore, the indirect effect was significant, β = .04 [.005–.104], p = .02, suggesting that the relationship between caregiving and CRP levels was partially explained by the greater occurrence of daily stressors among caregivers.

Figure 4.

Standardized regression weights of the structural equation model of the mediation effect of daily stressors on the relationship between caregiving and CRP levels. * denotes a significant path, p < .05. The regression weight of the relationship between caregiving and CRP when daily stressors are omitted from the model is in parenthesis.

The daily stressors by caregiving status interaction term did not significantly predict IL-6, β= .04, t(109) = .60, p = .62, R2 = .002, and CRP, β= .10, t(129) =.59, p = .56, R2 = .002. These results did not support the reactivity model given that caregiving status did not moderate the impact of daily stressors on systemic inflammatory markers; the magnitude of the inflammatory response was similar across caregivers and controls.

Characteristic of the caregiving experience

Caregivers had been caring for a loved one with dementia for an average of 56 months (SD=44). They spent an average of 8.21 (SD=7.92) hours per day in caregiving activity. About 42% of the caregivers were living with the patient and 46% considered themselves the only caregiver. The patient was a spouse for 18 caregivers and a parent for 35 caregivers. None of the characteristics of caregiving mentioned above were related to the number of stressors reported in the past 24 hours, and IL-6 and CRP levels, p > .16. Furthermore, the dementia severity and the caregiver’s depressive symptoms did not moderate the relationship between daily stressors and the inflammatory markers, p > .34.

Health behaviors, medication use and inflammatory responses to daily stressors

Adjustment for health behaviors such as smoking, caffeine and alcohol consumption, exercise, and sleep quality did not significantly alter the relationship between daily stressors and IL-6, β = .08, t(109) = 2.34, p = .02, R2 = .04, and CRP levels, β = .19, t(129) = 2.37, p = .02, R2 = .032. Similarly, when non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and antidepressant medication use were included in the model, daily stressors remained significantly associated with IL-6, β = .08, t(173) = 1.42, p = .03, R2 = .039, or CRP levels, β = .17, t(129) = 1.42, p = .04, R2 = .028.

Discussion

This study addressed the relationship among chronic stress, daily stressors, and inflammatory markers. In this study, naturally occurring daily stressors led to elevations in IL-6 and CRP levels similar to those found following exposure to a laboratory stressor (Steptoe, et al., 2007). However, in the present study the exposure to multiple stressors, not just one stressor, was associated with elevated inflammatory markers. Such a dose-response relationship has been observed in other studies of stress-induced increases in IL-6 (e.g., Zhou, Kusnecov, Shurin, DePaoli, & Rabin, 1993).

The data provided preliminary support for the exposure model, but not for the reactivity model. Mediation analyses suggested that chronic stress was associated with elevated inflammatory markers in part because of the higher frequency of daily stressors experienced by caregivers. This suggests that the effect of chronic stress on IL-6 and CRP might be attributable not only to the chronic nature of the stressors but also to the multiple recent stressful events experienced by these individuals.

Contrary to the assumptions of the reactivity model, caregivers and controls had similar IL-6 and CRP responses following the occurrence of multiple stressors in the past 24 hours. These results contrast with human laboratory studies in which chronic stress and depression heightened inflammatory responses to daily stressors (e.g., Pace, et al., 2006). The differences in timing of the measurements of inflammatory markers across studies may explain the discrepant finding. Furthermore, it is possible that the cumulative impact of several stressors may overshadow the increased reactivity associated with chronic stress; exposure to multiple stressors may lead to physiological changes that are larger than the increased reactivity associated with each stressor.

In the present study, caregiving stress was associated with heightened serum CRP levels which were not significantly related to IL-6 levels. This result is puzzling because caregivers reported more daily stressors than controls. The current sample differs from previous studies in the proportion of parental caregivers, the difference in marital status, and the age range included in the study. These differences may contribute to the lack of group differences in IL-6. Alternatively, missing IL-6 data may have diminished our statistical power to detect group differences.

To conclude, data from the current study extend laboratory evidence by showing that daily stressors can increase inflammatory biomarkers in naturalistic settings and provide preliminary support for the hypothesis that daily stressors partially mediate the impact of chronic stress on CRP production. However, the cross-sectional design limits the inferences that can be made from these data. Replication of these results with consecutive measurements of daily stressors and inflammatory biomarkers over several days is needed. If inflammatory markers remain elevated up to 24 hours after daily stressors, exposure to multiple daily stressors for several consecutive days is likely to have a much greater impact over time.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by NIH grants AG025732, UL1RR025755, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Grant CA16058, and a doctoral training award from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec. We appreciate the helpful assistance of Cathie Atkinson, Bryon Laskowski, and the Central Ohio Alzheimer's Association.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hea.

References

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkinjuntti T, Hokkanen L, Sulkava R, Palo J. The Blessed Dementia Scale as a screening test for dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1988;3:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire. Journal of Gerontology. 1981;36:428–434. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Telzer EH, Bower J, Cole SW, Kiang L, Irwin MR. A preliminary study of daily interpersonal stress and C-reactive protein levels among adolescents from Latin American and European backgrounds. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:329–333. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181921b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin JP, Hantsoo L, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Immune dysregulation and chronic stress among older adults: a review. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15:251–259. doi: 10.1159/000156468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, Glaser R. Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1377–1384. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Longo DL, Ferrucci L. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: A magnificent pathway. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61:575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace TWW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, et al. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1630–1632. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: A review and meta-analysis. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2007;21:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. doi: S0889-1591(07)00083-9 [pii]10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: Outcomes for interventions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33:1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Kusnecov AW, Shurin MR, DePaoli M, Rabin BS. Exposure to physical and psychological stressors elevates plasma interleukin 6: Relationship to the activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2523–2530. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]