Abstract

The research is aimed to explore the distinct molecular signatures in discriminating the rheumatoid arthritis patients with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) cold pattern and heat pattern. Twenty patients with typical TCM cold pattern and heat pattern were included. Microarray technology was used to reveal gene expression profiles in CD4+ T cells. The signal intensity of each expressed gene was globally normalized using the R statistics program. The ratio of cold pattern to heat pattern in patients with RA at more or less than 1:2 was taken as the differential gene expression criteria. Protein–protein interaction information for these genes from databases was searched, and the highly connected regions were detected by IPCA algorithm. The significant pathways were extracted from these subnetworks by Biological Network Gene Ontology tool. Twenty-nine genes differentially regulated between cold pattern and heat pattern were found. Among them, 7 genes were expressed significantly more in cold pattern. Biological network of protein–protein interaction information for these significant genes were searched and four highly connected regions were detected by IPCA algorithm to infer significant complexes or pathways in the biological network. Particularly, the cold pattern was related to Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. The following related pathways in heat pattern were included: Calcium signaling pathway; cell adhesion molecules; PPAR signaling pathway; fatty acid metabolism. These results suggest that better knowledge of the main biological processes involved at a given pattern in TCM might help to choose the most appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Protein and protein interaction, Genomics, Pathway, Rheumatoid arthritis, Traditional Chinese medicine

Introduction

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. Its world wide prevalence is approximately 1% [1]. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is widely used in China and was found to be effective in the treatment of RA [2]. Pattern differentiation in TCM, as the key term in TCM therapeutic theory, is based on the physiology and pathology of TCM [3]. The efficacy of TCM is entirely based on patterns differentiation, since the pattern guides the herbal medicine prescription [2, 4, 5]. Furthermore, our previous study showed the effective rate of the biomedical combination therapy was higher in the patients with a cold pattern than in patients with a hot pattern (P < 0.01) [6]. These different responses to the treatment made it reasonable to make the hypothesis that the heterogeneity of pattern in TCM is subsistent and it might have its own specific markers.

Following the TCM clinical practice, the patients with RA can be classified into two main patterns: the cold pattern and the heat pattern. The cold pattern can be described as severe pain in a joint or muscle that limits the range of comfortable movement which does not move to other locations. The pain is relieved by applying warmth to the affected area, but increases with exposure to cold. Loose stools are characteristic as well as an absence of thirst and clear profuse urine. A thin white tongue coating is seen, combined with a wiry and tight pulse. In contrast, the heat pattern is characterized by severe pain with hot, red, swollen and inflamed joints. Pain is generally relieved by applying cold to the joints. Other symptoms include fever, thirst, a flushed face, irritability, restlessness, constipation and deep-colored urine. The tongue may be red with a yellow coating and the pulse may be rapid [5, 6].

Nearly, every aspect of a disease phenotype should be represented in the pattern of genes and proteins that are expressed in the patient. The molecule signature typically represents characteristics and subtypes of the disease [7]. The advent of microarray technology has provided a powerful tool to gain insight into the molecular complexity of the diversity. Moreover, this technology facilitates to identify comprehensively the genes and biological pathway that are associated with different pattern in TCM. Preliminary work supports that CD4+ T cell plays a fundamental role in pathogenesis of RA [8, 9]. Hence, the identification of differentially molecule characteristic in CD4+ T cell can help to reveal the heterogeneity of the pattern in RA.

Here, in the present study, we applied gene expression profiling to CD4+ T cells from RA patient with cold pattern or heat pattern in TCM to try to indentify underlying biological and molecular difference of the pattern.

Materials and methods

Patients

Twenty female patients with RA from the Sino-Japan friendship hospital, aged from 12 to 68 years old (1 case was at age of 12, 7 cases were from age of 30 to 50, and 12 cases from age of 50–68) were eligible to participate if they met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for RA for at least 1 year with functional Class at level I, II, or III [10]. The patients with typical TCM cold pattern and heat pattern diagnosed according to TCM theory (RA with cold pattern showed no color change in joint, severe pain in cold condition; RA with heat pattern showed red joint, severe pain in hot condition) were collected in the study. Patients continuously receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids for over 6 months, or receiving the above-mentioned medicine with 1 month were not included in the study. Patients with severe cardiovascular, lung, liver, kidney, hematologic, or mental disease and women who were pregnant, breast-feeding, or planning to become pregnant in the next 8 months were excluded. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice (China).

Sample preparation

A volume of 6 ml venous blood was collected from all 20 participants (ten patients with heat pattern, ten patients with cold pattern) and 1 control before breakfast. CD4+ T cells were extracted and purified from the whole blood by RosetteSep® Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technologies, Inc., Vancouver, Canada). Total RNA was isolated from the CD4+ T cells using Trizol extraction method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Canada) as described by the manufacturer. mRNAs were amplified linearly using the MessageAmp™ aRNA Kit (Ambion, Inc., Austin, USA) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer. cRNA was purified with RNeasy® Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) based on a standard procedure. All arrays had the same label: Cy3 for sample and Cy5 for control.

Microarray assay

Two-color whole Human Genome Microarray Kit, 4 × 44 K (Agilent Technologies) was used in this study. Microarray hybridizations were carried out on labeled cRNAs. Arrays were incubated at 65°C for 17 h in Agilent’s microarray hybridization chambers and subsequently washed according to the Agilent protocol. Arrays were scanned at 5 μm resolution using GenePix Personal 4100A (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). Auto photomultiplier tube (PMT) gains were adjusted to obtain a ratio of Cy3 and Cy5 channels intensities.

Statistics and function analysis

All data were analyzed on a SAS9.1.3 statistical package (order no. 195557). The signal intensity of each expressed gene was globally normalized (LOWESS) using the R statistics program [11]. The ratio of cold pattern to heat pattern in patients with RA at more or less than 1:2 was taken as the differential gene expression criteria. Statistical significance was tested using the Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). The candidate genes were adjusted by Power Procedure of SAS software, which controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR). For the contrast, a gene is considered differentially expressed if the Power value is more than 0.85.

Protein–protein interactions (PPI) can be considered the basic skeleton for living organism self-organization and homeostasis [12]. In this study, information on human PPI network from these significant genes was obtained from Databases, including BIND (Biomolecular Interaction Network Database), BioGRID (The General Repository for Interaction Datasets), DIP (Database of Interacting Proteins), HPRD (Human Protein Reference Database), IntAct (Database system and analysis tools for protein interaction data), and MINT (Molecular Interactions Database), and complemented with curated relationships parsed from Literature using Agilent Literature Search. The PPI network was visualized using cytoscape [13].

We integrated the database and the networks (above mentioned) and then used IPCA to analyze the characteristics of the network. The IPCA algorithm can detect highly connected regions (or clusters) in the interactome network [14]. Interactomes with a score greater than 2.0 and at least four nodes were taken as significant predictions.

Further analysis of gene ontology categories was performed to indentify the function of each highly connected region generated by IPCA individually. The latest version of Biological Network Gene Ontology (BiNGO) tool [15] was used to statistically evaluate groups of proteins with respect to the existing annotations of the Gene Ontology Consortium. The degree of functional enrichment for a given cluster was quantitatively assessed (P value) by hypergeometric distribution, implemented in BiNGO tool. We selected the 5 GO biological categories with the smallest P values as significant.

Results

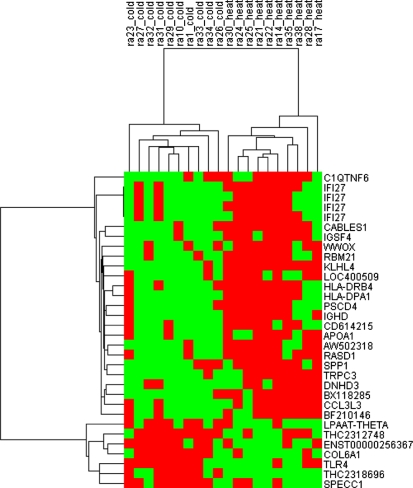

Using a t test, we identified a combination of 29 genes (IFI27 appeared 4 times) differentially regulated between cold pattern and heat pattern (Fig. 1, Table 1). These genes clearly separated cold pattern from heat pattern in RA. Among these 29 genes, 7 genes were expressed significantly more in cold pattern.

Fig. 1.

Cluster diagram of the expression of 29 significantly expressed genes in 10 RA patients with heat patterns and 10 RA patients with cold patterns. Patients are indicated as vertical column headings, and gene symbols of transcripts are given in horizontal rows. Red represents relative expression greater than the median expression level across all samples, and the green represents an expression level lower than the median

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in cold pattern versus heat pattern in patients with RA

| Feature num | Probe name | Gene name | Genbank accession | t | P | Cold/heat ratio | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18391 | A_23_P69810 | LPAAT-THETA | NM_032717 | 3.25 | 0.004 | 3.26 | 0.86 |

| 21788 | A_32_P32254 | COL6A1 | NM_001848 | 3.37 | 0.003 | 3.06 | 0.88 |

| 25197 | A_24_P273738 | ENST00000256367 | 3.62 | 0.002 | 2.89 | 0.93 | |

| 42510 | A_32_P205973 | THC2318696 | 3.28 | 0.004 | 2.5 | 0.86 | |

| 3539 | A_24_P943095 | SPECC1 | NM_001033553 | 3.77 | 0.001 | 2.25 | 0.94 |

| 22497 | A_23_P60306 | TLR4 | NM_138554 | 3.44 | 0.003 | 2.11 | 0.9 |

| 32104 | A_32_P156564 | THC2312748 | 3.31 | 0.004 | 2.07 | 0.86 | |

| 22042 | A_32_P107002 | LOC400509 | NM_001012391 | −3.44 | 0.003 | 0.49 | 0.89 |

| 27653 | A_32_P158376 | BF210146 | −3.21 | 0.005 | 0.48 | 0.85 | |

| 22242 | A_23_P422851 | CABLES1 | NM_138375 | −3.33 | 0.004 | 0.48 | 0.87 |

| 1946 | A_23_P203191 | APOA1 | NM_000039 | −3.35 | 0.004 | 0.47 | 0.88 |

| 18087 | A_32_P25623 | CD614215 | −3.64 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 0.93 | |

| 16000 | A_24_P324838 | IGHD | AK090461 | −4.31 | 0 | 0.47 | 0.98 |

| 35814 | A_23_P7313 | SPP1 | NM_000582 | −3.53 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 0.91 |

| 36150 | A_24_P116606 | WWOX | NM_130791 | −3.83 | 0.001 | 0.47 | 0.95 |

| 45184 | A_23_P155057 | PSCD4 | NM_013385 | −3.36 | 0.003 | 0.46 | 0.88 |

| 35889 | A_23_P359457 | DNHD3 | BC034225 | −3.44 | 0.003 | 0.45 | 0.9 |

| 38052 | A_24_P211565 | C1QTNF6 | NM_031910 | −3.36 | 0.003 | 0.43 | 0.88 |

| 20075 | A_32_P82265 | AW502318 | AW502318 | −4.91 | 0 | 0.41 | 1 |

| 18395 | A_32_P128023 | RBM21 | AK125351 | −3.82 | 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.95 |

| 18438 | A_32_P35759 | BX118285 | BX118285 | −3.96 | 0.001 | 0.35 | 0.96 |

| 42098 | A_24_P353486 | KLHL4 | NM_057162 | −4.88 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.99 |

| 14498 | A_23_P118392 | RASD1 | NM_016084 | −4 | 0.001 | 0.33 | 0.96 |

| 20670 | A_24_P243528 | HLA-DPA1 | NM_033554 | −3.58 | 0.002 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

| 30285 | A_23_P41455 | TRPC3 | NM_003305 | −3.31 | 0.004 | 0.26 | 0.87 |

| 22191 | A_23_P203120 | IGSF4 | NM_014333 | −3.39 | 0.003 | 0.22 | 0.89 |

| 29764 | A_24_P370472 | HLA-DRB4 | NM_021983 | −3.41 | 0.003 | 0.2 | 0.89 |

| 12088 | A_24_P228130 | CCL3L3 | NM_001001437 | −3.39 | 0.003 | 0.17 | 0.89 |

| 36112 | A_23_P48513 | IFI27 | NM_005532 | −3.19 | 0.005 | 0.09 | 0.85 |

| 37262 | A_23_P48513 | IFI27 | NM_005532 | −3.2 | 0.005 | 0.09 | 0.85 |

| 11288 | A_23_P48513 | IFI27 | NM_005532 | −3.33 | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.88 |

| 25357 | A_24_P270460 | IFI27 | NM_005532 | −3.66 | 0.002 | 0.07 | 0.93 |

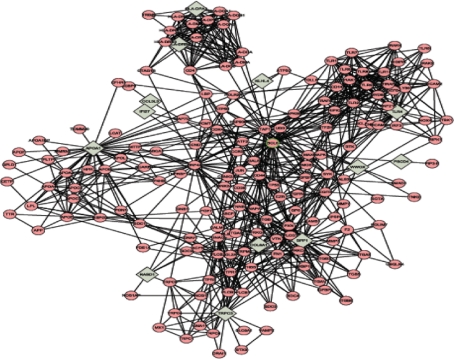

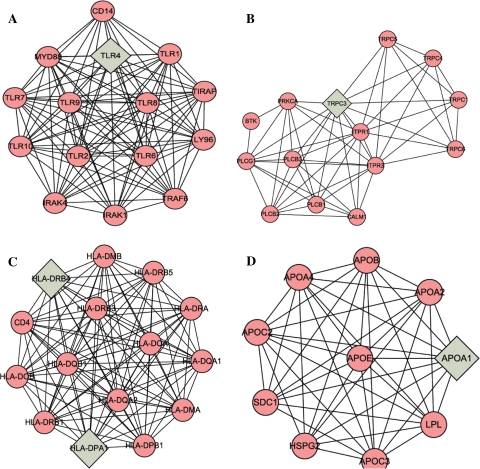

Biological network of protein–protein interaction information for these significant genes was searched and visualized using Cytoscape (Fig. 2). Four highly connected regions were detected by IPCA algorithm to infer significant complexes or pathways in the biological network (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Protein–protein interaction biological network about the significant genes. Cycles represent neighbor nodes. All edges represent interactions between the nodes. Diamonds represent seed node

Fig. 3.

Four sub-networks made up of highly connected regions were extracted from the biological network. Diamonds represent seed node

We used BiNGO tools to statistically evaluate groups of the genes with respect to the present annotation categories of the Gene Ontology Consortium. The most relevant function and pathways extracted from these 4 highly connected regions were involved in I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB cascade, inflammatory response, protein kinase cascade, innate immune response, defense response, immune system process (Table 2), integrin-mediated signaling pathway, cell adhesion, biological adhesion, cell-matrix adhesion, cell-substrate adhesion (Table 3), antigen processing and presentation of peptide, antigen processing and presentation, immune response, immune systems process, response to stimulus (Table 4), sterol transport, cholesterol transport, phospholipid efflux, cholesterol efflux, phospholipid transport, lipid transport (Table 5). Particularly, the cold pattern was related to Toll-like receptor signaling pathway (Fig. 3a). The following related pathways in heat pattern were included: Calcium signaling pathway (Fig. 3b); Cell adhesion molecules (Fig. 3c); PPAR signaling pathway, Fatty acid metabolism (Fig. 3d).

Table 2.

The gene ontology analysis of the sub-networks-A

| GO ID | Description | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 7249 | I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB cascade | 1.28E-28 |

| 6954 | Inflammatory response | 5.50E-19 |

| 7243 | Protein kinase cascade | 6.89E-19 |

| 45087 | Innate immune response | 8.06E-19 |

| 6952 | Defense response | 1.65E-15 |

Table 3.

The gene ontology analysis of the sub-networks-B

| GO ID | Description | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 7229 | Integrin-mediated signaling pathway | 8.82E-11 |

| 7155 | Cell adhesion | 1.62E-10 |

| 22610 | Biological adhesion | 1.62E-10 |

| 7160 | Cell-matrix adhesion | 1.78E-10 |

| 31589 | Cell-substrate adhesion | 2.59E-10 |

Table 4.

The gene ontology analysis of the sub-networks-C

| GO ID | Description | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 2504 | Antigen processing and presentation of peptide | 8.19E-42 |

| 19882 | Antigen processing and presentation | 1.36E-32 |

| 6955 | Immune response | 1.32E-21 |

| 2376 | Immune systems process | 7.36E-20 |

| 51869 | Response to stimulus | 7.11E-12 |

Table 5.

The gene ontology analysis of the sub-networks-D

| GO ID | Description | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 15918 | Sterol transport | 1.54E-19 |

| 30301 | Cholesterol transport | 1.54E-19 |

| 33700 | Phospholipid efflux | 5.40E-19 |

| 33344 | Cholesterole fflux | 2.97E-18 |

| 15914 | Phospholipid transport | 1.48E-15 |

Discussion

The clinical experience in TCM over its long history suggested that pattern differentiation has some role in the pathogenesis of disease and determination of treatment efficacy. The previous study suggested that the pattern differentiation in TCM in patients with RA had similar classification as those obtained from statistical-based clinical data [16]. Our study also showed this pattern differentiation in RA could affect the efficacy of the biomedical therapy [6]. This unprecedented information has implied the distinct basis of the pattern. Herein, we showed the gene expression profiling of the pattern differentiation in patients with RA revealed biological significance during the course.

In our study, a differential expression of 29 reference sequence genes (22 down-regulated and 7 up-regulated in cold pattern compared with the heat pattern) was observed. We identified a remarkably elevated expression of a spectrum of genes involved in collagen VI, pathogen recognition and activation of innate immunity in CD4+ T cell of cold pattern in patients with RA, whereas up-regulated genes in heat pattern participated in proliferation and/or differentiation, cholesterol efflux, regulation of cellular functions, regulation of protein sorting and membrane trafficking, immunoregulatory processes. Further analysis with PPI approach reveals two major interesting findings.

First, the Toll-like receptor (TLRs) signaling pathway was found to be related to the cold pattern. A previous report [17] showed the TLRs have been implicated in various inflammatory arthopathies. They recognize pathogen-derived factors and also products of inflamed tissue, and trigger signaling pathways that lead to activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and the interferon regulatory factors. These in turn lead to induction of immune and inflammatory genes, including such important cytokines as tumor necrosis factor-alpha and type I interferon [18]. Data also suggest that activation by endogenous TLR ligands may contribute to the persistent expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages and the joint damage to cartilage and bone that occurs in RA [19]. The TLR4 can engage with a pathway leading to the activation of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor-3. The interferon regulatory factor-3 is required for the induction of a wide range of pro-inflammatory cytokines [17]. The elevated TLR4 can be found in the rheumatoid synovial [20]. Moreover, in human macrophages and fibroblasts from synovial of individuals with RA, tenascin-C induces synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines via activation of TLR4 [21]. Ospelt C [22] prove that TLR3 and TLR4 are the most abundant among the TLR family in synovial fibroblasts in early RA patients, and stimulation of synovial fibroblasts with TCR3 ligand poly (I–C) led to the most pronounced increase in IL-6, MMP-3, and MMP-13. In our study, it implied that the inflammatory response is more pronounced in cold pattern than in the heat group. This finding correlates well with the fact that the effective rate of anti-inflammatory drugs in RA patients with cold pattern is higher than those with a heat pattern [6].

Interestingly, the NF-κB (Table 2), which can be activated by TLR, is an inducible transcription factor that is controlled by the signal activation cascades. NF-κB controls a number of genes involved in immunoinflammatory responses, cell cycle progression, inhibition of apoptosis, and cell adhesion, thus promoting chronic inflammatory responses. It induces gene expression of physiological inhibitors of apoptosis such as cIAPs, Bcl-XL, and cFLIP [23]. Moreover, it is shown that NF-κB can attenuate the TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in the absence of de novo protein synthesis [24] through PPI with p53 and proapoptotic protein 53BP2 [25, 26]. In contrast, the TRPC3 (Fig. 3b), which up-regulated in heat pattern, plays a role in the calcium ion transport. Overexpression TRPC3 can increase sensitivity to high extracellular calcium-induced apoptosis [27]. In the meantime, three genes involved in apoptosis, CABLES1, WWOX, and IFI27 are upregulated in RA heat pattern. Overexpression of CABLES1 results in a significant decrease in cell proliferation rate, which was associated with an increase in apoptosis [28]. WWOX is essential for TNF, UV, staurosporine, and p53-mediated apoptosis [29, 30]. Transient expression of IFI27 led to decrease viable cell numbers and enhance sensitivity to DNA-damage-induced apoptosis [31]. The results showed the differences in the regulation of apoptosis between cold pattern and heat pattern in patients with RA, which was already posed by our previous finding [32]. Owing to the induction of apoptosis of macrophages, synovial fibroblasts or lymphocytes, either through suppression of signaling pathways or inhibition of the expression of anti-apoptotic molecule, could be therapeutically beneficial in RA [33]. The heat pattern with a signature of induction of apoptosis implied a more brightly prognosis than the cold pattern.

Secondly, we also found calcium signaling pathway, cell adhesion molecules, PPAR signaling pathway, and fatty acid metabolism were related to heat pattern. Ca2+ signals are essential for diverse cellular functions including differentiation, effector function, and gene transcription in the immune system. In lymphocytes, sustained Ca2+ entry is necessary for complete and long-lasting activation of calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) pathways [34]. Resting lymphocytes maintain a low concentration of Ca2+. However, engagement of antigen receptors induces calcium influx from the extracellular space by several routes [35]. In T lymphocytes, store-operated Ca2+ -release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels constitute the sole pathway for Ca2+ entry following antigen-receptor engagement, and their function is essential for driving the program of gene expression that underlies T-cell activation by antigen [36]. Cell adhesion molecules expressed on the surface of immune cells transduce a variety of cell-activating signals and mediate important interactions by binding to multiple specific counter-receptors expressed on other cells or on extracellular matrix components [37]. T-cell extravasation into rheumatoid synovial tissue is a critical aspect of rheumatoid inflammation. Adhesion receptors play central roles in the pathogenesis of RA by mediating T-cell interactions with the endothelium and with the extracellular matrix (ECM), as well as by delivery of co-stimulatory signals to the cells [38, 39]. Regulation of signal transduction mediated by adhesion molecules on lymphocytes may be the possible effective way for controlling the pathological inflammatory process in RA [40]. Both calcium signaling pathway and cell adhesion molecules implied that T-lymphocyte interactions are of more importance in the heat pattern, and it could be a potential target for therapy. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear hormone receptors that are activated by fatty acids and their derivatives. PPAR has three subtypes (PPARalpha, beta/delta, and gamma) showing different expression patterns in vertebrates [http://www.genome.jp/kegg/]. Literature indicates that sophisticated manipulation of essential fatty acid (EFA) metabolism may have a role in rheumatological disorders [41]. The results suggest that PPAR signaling pathway and fatty acid metabolism might be directly or indirectly involved in RA pathogenesis in heat pattern, but the exactly effect is not well understood. Additional work is needed to investigate the mechanism.

In summary, our results show that the biological processes corresponding to the heat pattern in patients with RA mainly include apoptosis induction, T-cell interaction, and fatty acid metabolism. The results suggest that gene expression profiling could be used to some extent in discriminating groups of RA patients with cold or heat pattern. The discriminative power was partly validated by the clinical practice based on the clinical manifestations in TCM pattern differentiation, which is important for further stratification of disease [42]. This study is a step forward in TCM pattern differentiation study with distinctive biological markers.

Complex designs that include sample pooling, biological and technical replication, sample pairing, and dye-swapping are performed to reduce the systematic sources of variation in microarray experiments [43]. The repeated dye-swap experiment is useful for reducing technical variation, and the replicated dye-swap experiment is useful for comparing independent biological samples. It may be more difficult to achieve statistical significance using the replicated dye-swap experiment, especially if the biological variation is substantial [44]. In our study, the biological replication was used since the biological variation between cold pattern and heat pattern is the focus of the array design.

Conclusions

RA patients with TCM cold pattern and heat pattern have distinct molecular signatures with different biological processes participating. These results suggest that better knowledge of the main biological processes involved at a given pattern in TCM might help to choose the most appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by the projects from Ministry of Sciences and Technology (International Collaboration Project) 2006DFA31731, National Science Foundation of China, No. 90709007 and 30825047, and by E-institutes of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission No E03008.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Hochberg MC, Spector TD. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: update. Epidemiol Rev. 1990;12:247–252. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldbach Mansky R, Wilson M, Fleischmann R, Olsen N, Silverfield J, Kempf P, et al. Comparison of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F versus Sulfasalazine in the treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:229–240. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu A, Jia H, Xiao C, Lu Q. Theory of traditional Chinese medicine and therapeutic method of diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1854–1856. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i13.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai C, Kou J, Zhu D, Yan Y, Yu B (2010) Mice exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia simulates clinical features of deficiency of both Qi and Yin syndrome in traditional Chinese medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Jiang W. Therapeutic wisdom in traditional Chinese medicine: a perspective from modern science. Trends in Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu C, Zha Q, Chang A, He Y, Lu A. Pattern differentiation in traditional Chinese medicine can help define specific indications for biomedical therapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Altern Complement med. 2009;15:1021–1025. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Baarsen LG, Bos CL, w Kraan TC, Verweij CL. Transcription profiling of rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:207–219. doi: 10.1186/ar2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boissier MC, Assier E, Biton J, Denys A, Falgarone G, Bessis N. Regulatory T cells (Treg) in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cope AP, Schulze Koops H, Aringer M. The central role of T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(5 Suppl 46):S4–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin DM, Peng V, Ngai J, et al. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:15–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Real Chicharro A, Ruiz Mostazo I, Navas Delgado I, Kerzazi A, Chniber O, Sánchez Jiménez F, et al. Protopia: a protein-protein interaction tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(Suppl 12):S17–S27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S12-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Chen J, Wang J, Hu B, Chen G. Modifying the DPClus algorithm for identifying protein complexes based on new topological structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:398–413. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He Y, Lu A, Zha Y, Tsange I. Differential effect on symptoms treated with traditional Chinese medicine and western combination therapy in RA patients. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCormack WJ, Parker AE, O’Neill LA. Toll-like receptors and NOD-like receptors in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:243–250. doi: 10.1186/ar2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Neill LA, Bryant CE, Doyle SL. Therapeutic targeting of toll-like receptors for infectious and inflammatory diseases and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:177–197. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Q, Pope RM. The role of toll-like receptors in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:357–364. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0051-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brentano F, Kyburz D, Gay S. Toll-like receptors and rheumatoid arthritis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;517:329–343. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-541-1_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midwood K, Sacre S, Piccinini AM, Inglis J, Trebaul A, Chan E, et al. Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4 that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:774–780. doi: 10.1038/nm.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ospelt C, Brentano F, Rengel Y, Stanczyk J, Kolling C, Tak PP, et al. Overexpression of toll-like receptors 3 and 4 in synovial tissue from patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: toll-like receptor expression in early and longstanding arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3684–3692. doi: 10.1002/art.24140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto T. NF-kappaB and rheumatic diseases. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2006;6:359–372. doi: 10.2174/187153006779025685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kajino S, Suganuma M, Teranishi F, Takahashi N, Tetsuka T, Ohara H, et al. Evidence that de novo protein synthesis is dispensable for anti-apoptotic effects of NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2000;19:2233–2239. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang JP, Hori M, Takahashi N, Kawabe T, Kato H, Okamoto T. NF-kappaB subunit p65 binds to 53BP2 and inhibits cell death induced by 53BP2. Oncogene. 1999;18:5177–5186. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi S, Kajino S, Takahashi N, Kanazawa S, Imai K, Hibi Y, et al. 53BP2 induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial death pathway. Genes Cells. 2005;10:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shan D, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Overexpression of TRPC3 increases apoptosis but not necrosis in response to ischemia-reperfusion in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:833–841. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00313.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakamoto H, Friel AM, Wood AW, Guo L, Ilic A, Seiden MV, et al. Mechanisms of cables 1 gene inactivation in human ovarian cancer development. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:180–188. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.2.5253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aderca I, Moser CD, Veerasamy M, Bani Hani AH, Bonilla Guerrero R, Ahmed K, et al. The JNK inhibitor SP600129 enhances apoptosis of HCC cells induced by the tumor suppressor WWOX. J Hepatol. 2008;49:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang N, Doherty J, Ensign A, Schultz L, Hsu L, Hong Q. WOX1 is essential for tumor necrosis factor-, UV light-, staurosporine-, and p53-mediated cell death, and its tyrosine 33-phosphorylated form binds and stabilizes serine 46-phosphorylated p53. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43100–43108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosebeck S, Leaman DW. Mitochondrial localization and pro-apoptotic effects of the interferon-inducible protein ISG12a. Apoptosis. 2008;13:562–572. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Wietmarschen H, Yuan K, Lu C, Gao P, Wang J, Xiao C, et al. Systems biology guided by Chinese medicine reveals new markers for sub-typing rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:330–337. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181ba3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Pope RM. The role of apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:317–322. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh-hora M. Calcium signaling in the development and function of T-lineage cells. Immunol Rev. 2009;231:210–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vig M, Kinet JP. Calcium signaling in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luik RM, Lewis RS. New insights into the molecular mechanisms of store-operated Ca2+ signaling in T cells. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sfikakis PP, Mavrikakis M. Adhesion and lymphocyte costimulatory molecules in systemic rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s100670050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Postigo AA, García-Vicuña R, Laffón A, Sánchez-Madrid F. The role of adhesion molecules in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity. 1993;16:69–76. doi: 10.3109/08916939309010649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oppenheimer-Marks N, Lipsky PE. Adhesion molecules in rheumatoid arthritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1998;20:95–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00832001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sfikakis PP, Tsokos GC. Lymphocyte adhesion molecules in autoimmune rheumatic diseases: basic issues and clinical expectations. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13:763–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horrobin DF. Essential fatty acid and prostaglandin metabolism in Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1986;61:242–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu A, Chen K. Integrative medicine in clinical practice: from pattern differentiation in traditional Chinese medicine to disease treatment. Chin J Integr Med. 2009;15:152. doi: 10.1007/s11655-009-0152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Altman N and Replication Variation and normalisation in microarray experiments. Appl Bioinformatics. 2005;4:33–44. doi: 10.2165/00822942-200504010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Churchill GA. Fundamentals of experimental design for cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 2002;32(Suppl):490–495. doi: 10.1038/ng1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]