Abstract

Aromatase is the rate-limiting enzyme in estrogen biosynthesis. As a cytochrome P450, it utilizes electrons from NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) to produce estrogen from androgen. Estrogen is a key factor in the promotion of hormone-dependent breast cancer growth. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are drugs that block estrogen synthesis, and are widely used to treat estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Structure–function experiments have been performed to study how CPR and AIs interact with aromatase to further the understanding of how these drugs elicit their effects. Our studies have revealed a strong interaction between aromatase and CPR, and that the residue K108 is situated in a region important to the interaction of aromatase with CPR. The published X-ray structure of aromatase indicates that the F221, W224 and M374 residues are located in the active site. Our site-directed mutagenesis experiments confirm their importance in the binding of the androgen substrate as well as AIs, but these residues interact differently with steroidal inhibitors (exemestane) and non-steroidal inhibitors (letrozole and anastrozole). Furthermore, our results predict that the residue W224 also participates in the mechanism-based inhibition of exemestane, as time-dependent inhibition is eliminated with mutation on this residue. Together with previous research from our laboratory, this study confirms that W224, E302, D309 and S478 are important active site residues involved in the suicide mechanism of exemestane against aromatase.

Keywords: Aromatase, Androstenedione, Letrozole, Exemestane, Site-directed mutagenesis

1. Introduction

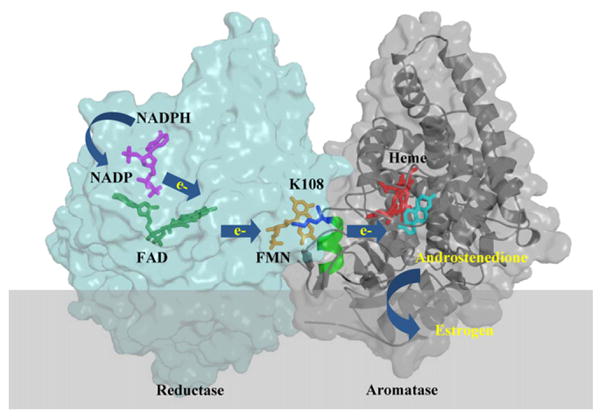

Aromatase, a cytochrome P450 enzyme, catalyzes three consecutive hydroxylation reactions to convert C19 androgen to aromatic C18 estrogen. After estrogen is synthesized by aromatase, it binds to the estrogen receptor (ER) to form an estrogen–ER complex. This estrogen-bound ER activates target genes that promote the growth of estrogen-dependent breast carcinomas. During estrogen biosynthesis, aromatase forms an electron transfer complex with the NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR). In the past two decades, researchers have analyzed the interactions between the members of cytochrome P450 family and the CPR enzyme. Structural data showed that the CPR enzyme consists of the following electron transfer domains: NADP-binding domain, FAD-binding domain and FMN-binding domain [1]. During the synthesis of estrogen, electrons are transferred from NADPH through the FAD and FMN domains of CPR to the heme of aromatase (Fig. 1). The recently solved crystal structure of the aromatase-androstenedione complex [2] provides structural information on how androgen binds at the active site of aromatase. This protein (residues 45–495) contains twelve α-helices (labeled from A to L) and ten β-strands (numbered from 1 to 10). The active site of aromatase was found to be relatively small (<400Å3), and the androgen molecule fits tightly into this androgen-specific cleft. The opening of the active site channel rests on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and allows the substrate to enter directly from the membrane site [2]. Based on the three-dimensional structural information from the CPR and aromatase crystals, we initiated a study to address a fundamental question: In what form does the aromatase–CPR complex exist under cellular conditions? The molecular docking model of the aromatase–CPR complex, published from our laboratory [3], revealed that the FMN domain of CPR undergoes a structural rearrangement, allowing the proximal surface of aromatase to fit into the cleft between the FMN and FAD domains of reductase. We identified key residues, including K108 on the surface of aromatase, which are involved in the interaction with reductase [3].

Fig. 1.

Schematic demonstration of the CPR–aromatase complex model. NADP (purple), FAD (green), FMN (orange), heme (red) and androstenedione (cyan) are shown in stick representation. During the synthesis of estrogen, electrons are transferred from NADPH, through FAD and FMN of CPR (light blue) to the heme of aromatase (grey). The K108 (blue) residue is located at the B′ helix (green) of aromatase and plays an important role in CPR and aromatase interaction and the electron transfer process. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

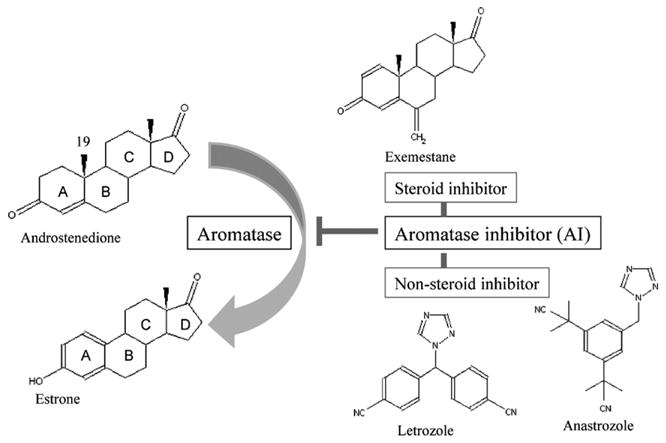

About 60 percent of premenopausal and 75 percent of post-menopausal breast cancer patients have estrogen-dependent carcinomas [4]. To treat these patients, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved three aromatase inhibitors (AIs): exemestane, letrozole and anastrozole. These AIs showed greater clinical benefits with higher specificity than anti-estrogen drug tamoxifen. These drugs were also found to effectively decrease recurrence rates of the hormone-dependent breast cancer [5–10]. Exemestane [brand name: Aromasin] is a steroidal aromatase inhibitor that primarily affects enzyme catalysis by binding as a pseudo substrate (Fig. 2), making it a mechanism-based inhibitor. The reactive intermediate of exemestane irreversibly binds to aromatase and causes permanent inhibition of the enzyme. Due to structural similarity with the substrate, it is easier to predict the interaction of exemestane with aromatase [2,11]. Alternatively, letrozole [brand name: Femara] and anastrozole [brand name: Arimidex] are not androgen analogues and are referred to as non-steroidal inhibitors. These two AIs contain a triazole functional group, which perturbs the catalytic properties of the heme prosthetic group of aromatase, and act as competitive inhibitors with respect to the androgen substrate [12]. The exact nature of non-steroidal inhibitor interactions with aromatase is still unclear due to their structural diversity. In our laboratory, we have performed site-directed mutagenesis experiments to evaluate how steroidal and nonsteroidal AIs bind to the active site of aromatase. These results will be discussed in this paper.

Fig. 2.

Structures of androstenedione, estrone, exemestane, letrozole and anastrozole.

2. Molecular characterization of the aromatase–NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) complex

One of the research goals of our laboratory is to analyze the interaction of aromatase with its electron transfer partner, CPR. Our published data from the last two years are reviewed here. To study aromatase–CPR interaction, we used ZDOCK software to apply a flexible, step-wise docking approach. At first, aromatase was docked together with the FMN domain of reductase. The FAD and NADP domains were then added into the complex. The first support of the model came from the distance between FMN and heme which was found to be 18.8Å [3]. This distance corresponds to the one found in the crystal structure of the bacterial cytochrome P450BM–3 complex, where the heme and the reductase domains linked together on a single polypeptide chain [13]. Earlier sequence alignment data noted five positively charged amino acids of cytochrome P450 that are present at the CPR interaction surface [14–16]. For aromatase, the corresponding residues are K99, K108, K389/K390, K420 and R425. In our model, we noticed interactions between the K108 and K420 residues of aromatase with the N175/T177 and E115 residues of CPR, respectively.

Based on our structural model, we investigated the role of the K108 residue in detail through site-directed mutagenesis. The conserved K108 residue is located on the B′ helix of aromatase, and the B′ helix intrudes into the cleft between the FMN and FAD domains of reductase (Fig. 1). We generated a K108Q mutant in CHO cells, and used the ‘in cell’ aromatase assay to measure and compare enzyme activity between the wild-type and the mutant proteins. Results from Western blot analysis showed that similar protein levels were detected in the wild-type and mutant expressed cells, but a significant decrease in aromatase activity was observed in the K108Q cells [3]. We then performed kinetic analyses with recombinant CPR and aromatase enzymes from Escherichia coli to determine if the decreased activity was due to a change in CPR–aromatase interaction. Results showed that the Km value of CPR for the interaction with the K108Q mutant (20 nM) was twentyfold weaker than the wild-type aromatase (1 nM). Our kinetic analysis further showed that the K108Q mutant had a similar androstenedione binding affinity as the wild-type protein. Therefore, the decreased activity of the K108Q mutant is most likely due to a decrease in the efficiency of the electron transfer process from CPR to aromatase. The IC50 values (half maximal inhibitory concentration) of exemestane were equivalent for the K108Q mutant and the wild-type protein (unpublished data). In addition, the time–dependent inhibition profile of exemestane, for both the mutant and the wild-type protein, was also similar. Thus, our data indicated that the K108 residue has no role in either substrate or inhibitor binding. We accordingly proposed that the K108 residue is present at the binding surface that interacts with reductase and may be important for maintaining the local environment for the electron transfer process during estrogen synthesis.

3. Binding mechanisms of aromatase inhibitors

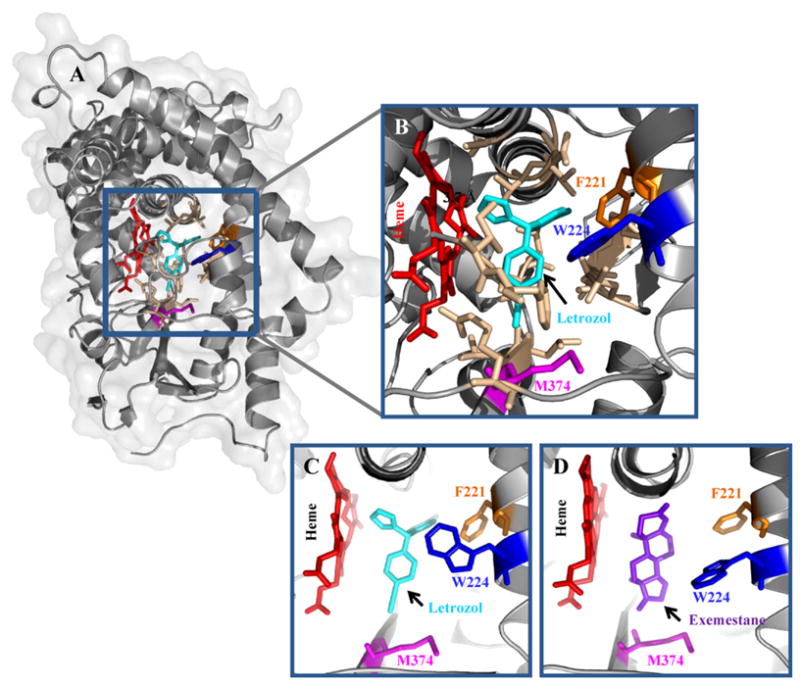

To better understand how AIs' function, we also study how AIs interact with aromatase. Extensive site-directed mutagenesis experiments have been carried out in our laboratory to identify a number of amino acid residues in the active site of aromatase and to predict their functional roles in catalysis and in the interaction with AIs [12,17–19]. While the recently reported X-ray aromatase structure confirms our previous observations, several new active site residues have been revealed [2]. The crystal structure of the aromatase–androstenedione complex only portrays the substrate binding event of the enzyme, not the binding of the inhibitors (particularly nonsteroidal inhibitors). The residues comprising the active cleft of aromatase were identified as: I305, A306, D309 and T310 from the I–helix, F221 and W224 from the F–helix, I133, F134 from the B–C loop, V370, L372 and V373 from the K-helix-β3 loop, M374 from β3 and L477 and S478 from the β8 to β9 loop [2,11,20]. The side chains of F221 and M374 residues were proposed to form van der Waals interactions with androstenedione [2]. We recently further examined the aromatase–nonsteroidal inhibitor interaction by docking letrozole into the published aromatase structure (Fig. 3) using Glide Docking (Maestro, Schrödinger) software. The distance between the heme of aromatase and the triazole functional group of letrozole in our current model was 3.7Å. Fifteen amino acids were found within a 4Å distance of the modeled letrozole structure (Fig. 3B). The residues were: I133, F134, F221, W224, A306, D309, T310, V313, V369, V370, V373, M374, L477, S478, and H480. In our previous papers, we examined the roles of many of these active site residues through site-directed mutational studies [12,17,21]. We observed a decreased letrozole binding affinity to the D309A mutant. In contrast, the E302D and T310S mutants showed an increase in letrozole binding.

Fig. 3.

Docking model of aromatase–letrozole complex. (A) Letrozole (cyan) is docked at the active site of aromatase. (B) Fifteen amino acids (light brown) were located within a 4 distance of letrozole in this model. The F221, W224 and M374 residues were colored in orange, blue and magenta, respectively. The distance between the heme (red) and the triazole functional group of letrozole in our current model is 3.7Å. (C) Aromatase–letrozole and (D) aromatase–exemestane models showing the F221, W224 and M374 residues. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

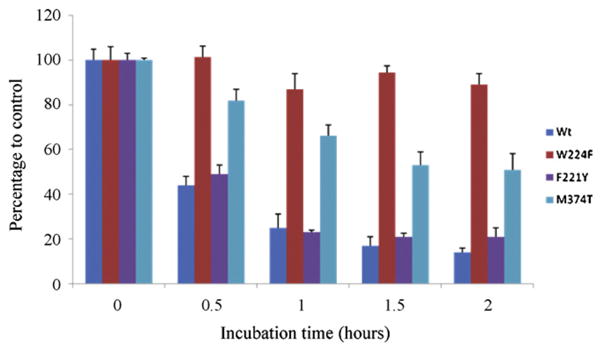

Recently, we investigated the changes in binding affinities of letrozole and androstenedione following mutagenesis on three newly identified active site residues: F221, W224, and M374. We generated three new mutants: F221Y, W224F, and M374T and compared their ‘in-cell’ aromatase activity (Table 1). The substrate binding properties of the mutants were determined by measuring their Km and Vmax values. We found a significant decrease in the catalytic activities in all three mutant proteins. A twofold weaker androstenedione binding was observed in the W224F mutant. In contrast, tight substrate binding was detected in the F221Y and M374T mutants, assuming that the Km values could be considered as relative dissociation constants for the substrate. Letrozole had an IC50 value (2 nM) for the wild-type aromatase, however stronger letrozole binding in the three mutants was noted: F221Y (0.22 nM), W224F (0.36 nM), and M374T (0.82 nM). Based on these results, we hypothesize that the structural change from a polar amino acid (Phe) to a nonpolar (Tyr) at F221 might re-arrange the binding pocket of aromatase. Furthermore, the change from Met to Thr at M374 may decrease the steric clash at the active site. These two mutations, therefore, may allow androstenedione and letrozole to bind tightly. Interestingly, exemestane inhibits both M374T and the wild-type aromatase with similar potency (Table 1), but it is a less effective mechanism-based inhibitor of M374T than the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of aromatase.

| Aromatase | Aromatase inhibitors (IC50) | Androstenedione | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letrozole (nM) | Exemestane (nM) | Km (nM) | Vmax (pmol/mg/h) | |

| WT | 2.0 + 0.1 | 15.0 + 2.0 | 27.3 ± 2.5 | 31.9 + 3.2 |

| F221Y | 0.22 + 0.03 | 35.0 + 3.0 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 7.3 + 1.0 |

| W224F | 0.36 + 0.02 | 700.0 + 36.0 | 67.0 ± 5.1 | 7.1 + 0.8 |

| M374T | 0.82 + 0.05 | 20.0 + 1.0 | 17.8 ± 2.0 | 2.7 + 0.4 |

Fig. 4.

Inhibition analysis of human aromatase by exemestane in CHO cells. Time-dependent inhibition of aromatase by exemestane was observed in the wild-type, F221Y and M374T mutants. However, the inhibition mechanism could not be clearly identified in the W224F mutant.

We also evaluated the role of W224 in substrate and inhibitor binding. Aromatase activity was significantly reduced when W224 was mutated to the charged residue Arg (unpublished data), preventing further analysis. The W224F mutant showed lower aromatase activity than the wild-type protein (Table 1). The decreased binding affinity of androstenedione and exemestane in the W224F mutant suggested that the W224 residue has a role in steroid binding. In the current model of the aromatase–letrozole complex, residue W224 is located within 4Å distance of letrozole (Fig. 3). By mutating the W224 residue, we were able to observe an increased binding affinity of letrozole. The structural differences between the side chains of Phe and Trp might facilitate letrozole binding at the active site of aromatase. However, the smaller side chain of Phe may be too far away from androstenedione to form the van der Waals interaction. This may result in decrease binding affinity for both androstenedione and exemestane (Table 1).

We also performed an inhibitory profile analysis of exemestane. As mentioned earlier, exemestane is a mechanism–based inhibitor. A definitive time-dependent inhibition by exemestane was observed in the wild-type, F221Y and M374T mutants. However, time-dependent inhibition could not be demonstrated in the W224F mutant (Fig. 4). We therefore suggest that the W224F mutation inhibits the formation of the reactive intermediate of exemestane. We have previously noted that the D309 residue participates in the irreversible mechanism of exemestane's inhibition of aromatase [11]. However, a detailed study is needed to allow us to determine a mechanistic insight into these two residues: W224 and D309.

4. Discussion

In this report, we first reviewed the findings from our proposed computer-assisted docking model of the aromatase–CPR complex. By performing additional biochemical experiments, including site-directed mutagenesis and kinetic analysis, we found that the K108 residue plays an important role in the association with CPR during estrogen synthesis. We observed that this effect was confined only at the aromatase–CPR interaction surface. We were unable to see any significant affect on either the substrate or the inhibitor binding in the K108Q mutant. The time-dependent inhibition profile of exemestane was also similar in both the wild-type and the mutant. From these data we concluded that the K108 residue may be responsible for protein–protein interactions and not in the active site events. Without a crystal structure of the aromatase–reductase complex, our studies provide critical information on how aromatase and reductase interact with each other on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Our analysis also reveals that K108 is away from an epitope recognized by an important aromatase antibody MCA677 [3].

Furthermore, we commented on the androstenedione, exemestane and letrozole recognition properties of aromatase. We discussed the interactions of three active site residues (F221, W224 and M374) with androstenedione and letrozole. F221Y and M374T mutants increased the binding affinity for both androstenedione and letrozole. Alternatively, the W224F mutant showed a different binding mechanism. Androstenedione and exemestane bind weaker and letrozole binds stronger to W224F than the wild-type enzyme. In addition, time-dependent inhibition of exemestane could not be demonstrated in the W224F mutant, confirming that W224 is involved in exemestane binding. Together with previous research from our laboratory, this study confirms that W224, E302, D309 and S478 are important active site residues involved in the suicide mechanism of exemestane against aromatase.

Clinically, anastrozole, exemestane and letrozole have been demonstrated to be AIs with outstanding specificity and potency. The structure–function studies, including both structural and biochemical analyses, are important ways to unravel the binding mechanisms of these inhibitors. The information will be valuable in the design of new treatment strategies of hormone-dependent breast cancer with AIs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants CA44735 and ES08258. We thank Dr. L. Adams, Dr. Y. Wang and the members of the Chen group for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wang M, Roberts DL, Paschke R, Shea TM, Masters BS, Kim JJ. Three-dimensional structure of NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase: prototype for FMN- and FAD-containing enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8411–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh D, Griswold J, Erman M, Pangborn W. Structural basis for androgen specificity and oestrogen synthesis in human aromatase. Nature. 2009;457:219–23. doi: 10.1038/nature07614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong Y, Li H, Ye J, Miki Y, Yuan YC, Sasano H, et al. Epitope characterization of an aromatase monoclonal antibody suitable for the assessment of intratumoral aromatase activity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S. Aromatase, breast cancer. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d922–33. doi: 10.2741/a333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, Paridaens R, Jassem J, Delozier T, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton JH, Klijn JG, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2131–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thurlimann B, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, et al. Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:486–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, Robert NJ, Muss HB, Piccart MJ, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1793–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Masri S, Hong Y, Wang X, Phung S, Yuan YC, et al. New experimental models for aromatase inhibitor resistance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;106:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong Y, Yu B, Sherman M, Yuan YC, Zhou D, Chen S. Molecular basis for the aromatization reaction and exemestane-mediated irreversible inhibition of human aromatase. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:401–14. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao YC, Cam LL, Laughton CA, Zhou D, Chen S. Binding characteristics of seven inhibitors of human aromatase: a site-directed mutagenesis study. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3451–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sevrioukova IF, Li H, Zhang H, Peterson JA, Poulos TL. Structure of a cytochrome P450-redox partner electron-transfer complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:18638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernhardt R, Kraft R, Otto A, Ruckpaul K. Electrostatic interactions between cytochrome P-450 LM2 and NADPH–cytochrome P-450 reductase. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1988;47:581–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu T, Tateishi T, Hatano M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Probing the role of lysines and arginines in the catalytic function of cytochrome P450d by site-directed mutagenesis. Interaction with NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3372–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stayton PS, Sligar SG. The cytochrome P-450cam binding surface as defined by site-directed mutagenesis and electrostatic modeling. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7381–6. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao YC, Korzekwa KR, Laughton CA, Chen S. Evaluation of the mechanism of aromatase cytochrome P450. A site-directed mutagenesis study. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:243–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadohama N, Yarborough C, Zhou D, Chen S, Osawa Y. Kinetic properties of aromatase mutants Pro308Phe, Asp309Asn, and Asp309Ala and their interactions with aromatase inhibitors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;43:693–701. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90295-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou DJ, Korzekwa KR, Poulos T, Chen SA. A site-directed mutagenesis study of human placental aromatase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:762–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh D, Griswold J, Erman M, Pangborn W. X-ray structure of human aromatase reveals an androgen-specific active site. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong Y, Li H, Yuan YC, Chen S. Molecular characterization of aromatase. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1155:112–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]