Abstract

We present a case of developmental venous anomaly associated with arteriovenous fistula supplied by a single arterial feeder adjacent to a large acute intracerebral hemorrhage. The arteriovenous fistula was successfully obliterated by superselective embolization while completely preserving the developmental venous anomaly. Two similar cases, including superselective angiographic findings, have been reported in the literature; however, we describe herein superselective angiographic findings in more detail and demonstrate the arteriovenous shunt more clearly than the previous reports. In addition, a literature review was performed to discuss the association of a developmental venous anomaly with vascular lesions.

Keywords: Arteriovenous fistula, Cerebral angiography, Cerebral hemorrhage, Developmental venous anomaly, Therapeutic embolization

INTRODUCTION

This report describes a case of an unusual developmental venous anomaly (DVA) which presented as intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) associated with a single arteriovenous fistula (AVF) demonstrated by superselective angiography and treated by endovascular glue embolization and to review relevant literatures.

CASE REPORT

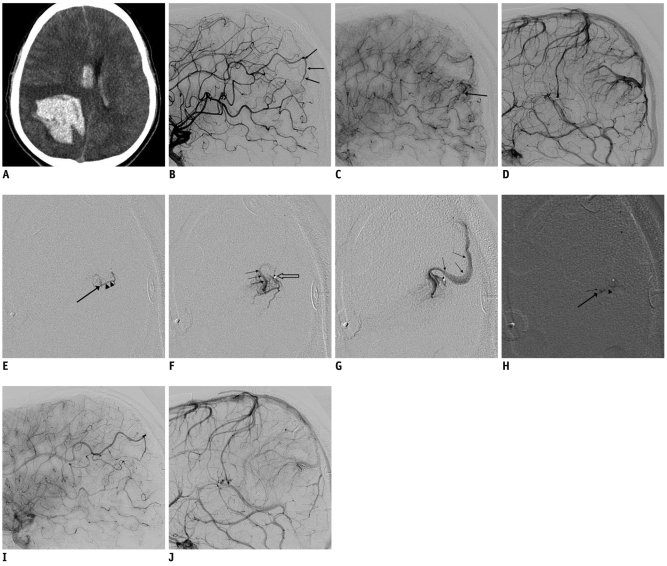

An 18-year-old male presented with sudden-onset drowsy mentality and vomiting during physical exercise, 30 minutes before admission in addition to left upper and lower extremity weakness (grade III/V). His initial Glasgow coma scale score was 13 (E3V4M6) and initial brain CT performed with a 64-slice multidetector scanner (Brilliance 64, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH) immediately after admission. The CT revealed severe ICH with surrounding brain edema in the right parietal lobe and IVH in the bilateral lateral, 3rd and 4th ventricles (Fig. 1A). Three-dimensional computerized tomographic angiography performed on the admission day showed no vascular abnormality suggesting ICH. The patient's symptoms improved significantly after surgically removing the hematoma. A post-operative neuroangiography was performed (Integris Allura; Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) to highlight a prominent distal parietal branch of the pericallosal artery of the right anterior cerebral artery; in the late arterial phase, dilated medullary veins and caput medusae appearance of a DVA were seen. A venous phase angiogram showed a similar DVA (Fig. 1B-D).

Fig. 1.

18-year-old male with atypical developmental venous anomaly.

A. Initial precontrast brain CT image showing large intracerebral hemorrhage in right parietal lobe and intraventricular hemorrhage in bilateral lateral ventricles. B. Right internal carotid angiogram of lateral image showing arterial pedicle (arrows) from pericallosal branch of right anterior cerebral artery. C. Late arterial phase angiogram showing early venous drainage (arrow). D. Developmental venous anomaly visualized in right parietal lobe in venous phase. E-G. Serial microangiogram clearly demonstrating arterial pedicle (arrowheads), site of arteriovenous fistula (large arrow) and early venous drainage (small arrows). Venous drainage from arteriovenous fistula shares venous channel of developmental venous anomaly showed in D and tip of microcatheter (open arrow) is also seen. H. Cast of NBCA-Lipiodol is located in distal arterial pedicle (arrowhead), arteriovenous fistula (large arrow), and venous channel just distal to arteriovenous fistula (small arrow). I, J. Late arterial phase lateral projection image (I) showing delayed flow in pedicle along with no arteriovenous shunt in post-embolization angiogram. Developmental venous anomaly still persists in venous phase (J) after embolization.

The superselective angiography clearly showed a single arterial feeder from the dilated distal parietal branch of the right pericallosal artery, and a single AVF; this fistula shared the DVA-like venous channel (Fig. 1E-G). To prevent further hemorrhage, 33% n-butyl cyanoacrylate-Lipiodol mixture was injected at several millimeters proximal to the AVS (Fig. 1H). After glue embolization of the AVF, early venous drainage disappeared and DVA was visualized only in the venous phase during control angiography (Fig. 1I, J). The early postembolization recovery was satisfactory and the patient was discharged one week after embolization with symptomatic sequelae as a result of ICH. At five months after embolization, the patient remains clinically stable.

DISCUSSION

Vascular malformations in the central nervous system have traditionally been classified into four categories: arteriovenous malformations, capillary telangiectasia, venous malformations and cavernous malformations (1). DVAs have been known by a variety of terms, including venous malformation, medullary venous malformation and venous angioma (1).

According to Hussain et al. (2) and Mullan et al. (3), DVAs represent an arrest during the development of the venous system, which results in the retention of primitive embryological medullary veins draining into a single large vein. DVAs are not always detected on computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance image (MRI), but they are never angiographically occult. Characteristically, DVAs have numerous dilated deep medullary veins presenting in "spoke wheel" or caput medusae configurations, which drain into a few dilated deep and/or superficial veins. Angiographically, the arterial phase of a DVA is normal and the venous phase shows one or more enlarged draining veins (2, 4).

The most common vascular anomaly associated with a DVA is a cavernous angioma, which occurs in 8% to 33% of patients (2, 4). They also coexist with AVF or capillary telangiectasia (5). The association of DVA and arteriovenous malformation (AVM) seems to be the least common (5). There have been several reports describing hybrid malformations consisting of an AVM and DVA as a rare subset of mixed cerebrovascular malformations (3, 6-12). The majority of the reported hybrid cases were in fact a combination of typical DVAs and additional AVFs (3, 6-12). These lesions have been variously described as follows: mixed malformations of atypical AVMs and venous angiomas, arterialized venous anomalies, atypical AVMs, transitional forms between venous malformations and AVMs, AVMs draining into a large DVA, or small AVMs with venous predominance (5, 13).

Mullan and colleagues (3) presented a particularly detailed analysis of the angiographic characteristics of DVAs associated with AVFs. All of them featured the classic star cluster of a DVA, but additionally exhibited arterial fistulizations.

Im et al. (13) reported a series of 15 patients with intracranial vascular malformations that were angiographically classified as atypical DVAs with arteriovenous shunts. This type of vascular malformation showed a fine arterial blush without a distinct nidus and early filling of the dilated medullary vein that drained these arterial components during the arterial phase on angiography. An angiographically defined arterial feeding vessel was noted in only one case and a preoperative embolization was performed. It was tabulated as one of their cases with no representative figures showing the vascular lesion.

Similarly, two cases have been reported by Fok et al. (11) who showed unusual DVA combined with an AVF by superselective angiography. However, they did not describe the detailed superselective angiographic findings. In contrast, we clearly demonstrated the angioarchitecture of atypical DVAs associated with single AVSs.

The potential risk of a DVA appears to be due to its frequent association with other vascular lesions, which are under-recognized (5). It has been suggested that the majority of hemorrhagic changes found in DVA territories are usually due to their associated cavernous malformations (1, 2). Also, many authors suggested that arterialized DVAs or DVAs with AVM are at greater risk to developing complications than simple DVAs, and that their natural history resembles that of classic AVMs (8, 10, 13, 14). In addition, we confirmed that an associated AVF was the cause of spontaneous ICH in DVA by angiography. Increased systemic venous pressure or increased local venous pressure secondary to stenosis of the draining transparenchymal vein or other venous obstruction could lead to hemorrhagic or ischemic complications (2).

Recent knowledge of the benign nature of a DVA without AVF encourages a more conservative approach (1, 14). The risk of cerebral venous infarction occurring after excision or obliteration of a DVA is significant and well known (15). Consequently, when an AVM and a DVA coexist, it is advisable to treat the AVM while preserving the DVA, which should serve as an important channel of the venous drainage from the regional brain (15).

Komiyama et al. (14) postulated that the prognosis of DVA with an AVF seems to be essentially as benign as that of a DVA without an AVF; hence, conservative treatment is recommended, except for cases with a large hematoma or with a coexisting AVM or a symptomatic, accessible cavernous angioma, which may be treated by surgical intervention. To treat a case of DVA associated with an AVM could be a challenge because resection will necessarily lead to an unfavorable alteration in the hemodynamic situation, with the removal of the venous drainage of nearby normal parenchyma (5).

In conclusions, the case presented here clearly demonstrated the detailed angiographic findings of atypical DVA associated with an AVF, including the arterial feeder, shunt site, and draining vein by superselective angiography. Furthermore, the angioarchitecture described in this case would help understand a rare subtype of cerebral vascular malformation.

References

- 1.Abe T, Singer RJ, Marks MP, Norbash AM, Crowley RS, Steinberg GK. Coexistence of occult vascular malformations and developmental venous anomalies in the central nervous system: MR evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:51–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussain JZ, Ray A, Hughes DG, Leggate JR. Complex developmental venous anomaly of the brain. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:501–504. doi: 10.1007/s007010200073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullan S, Mojtahedi S, Johnson DL, Macdonald RL. Cerebral venous malformation-arteriovenous malformation transition forms. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:9–13. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.1.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirin S, Kahraman S, Gocmen S, Erdogan E. A rare combination of a developmental venous anomaly with a varix. Case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:156–159. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/1/2/156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksoy FG, Gomori JM, Tuchner Z. Association of intracerebral venous angioma and true arteriovenous malformation: a rare, distinct entity. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:455–457. doi: 10.1007/s002340000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindquist C, Guo WY, Karlsson B, Steiner L. Radiosurgery for venous angiomas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:531–536. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.4.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fierstien SB, Pribram HW, Hieshima G. Angiography and computed tomography in the evaluation of cerebral venous malformations. Neuroradiology. 1979;17:137–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00339870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awad IA, Robinson JR, Jr, Mohanty S, Estes ML. Mixed vascular malformations of the brain: clinical and pathogenetic considerations. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:179–188. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199308000-00001. discussion 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer B, Stangl AP, Schramm J. Association of venous and true arteriovenous malformation: a rare entity among mixed vascular malformations of the brain. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:141–144. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.1.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirata Y, Matsukado Y, Nagahiro S, Kuratsu J. Intracerebral venous angioma with arterial blood supply: a mixed angioma. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fok KF, Holmin S, Alvarez H, Ozanne A, Krings T, Lasjaunias PL. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage caused by an unusual association of developmental venous anomaly and arteriovenous malformation. Interv Neuroradiol. 2006;12:113–121. doi: 10.1177/159101990601200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oran I, Kiroglu Y, Yurt A, Ozer FD, Acar F, Dalbasti T, et al. Developmental venous anomaly (DVA) with arterial component: a rare cause of intracranial haemorrhage. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s00234-008-0456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Im SH, Han MH, Kwon BJ, Ahn JY, Jung C, Park SH, et al. Venous-predominant parenchymal arteriovenous malformation: a rare subtype with a venous drainage pattern mimicking developmental venous anomaly. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:1142–1147. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/6/1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komiyama M, Yamanaka K, Iwai Y, Yasui T. Venous angiomas with arteriovenous shunts: report of three cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1328–1334. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199906000-00100. discussion 1334-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurita H, Sasaki T, Tago M, Kaneko Y, Kirino T. Successful radiosurgical treatment of arteriovenous malformation accompanied by venous malformation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:482–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]