Abstract

Aggressive angiomyxoma is an uncommon mesenchymal myxoid tumor that is characterized by slow growth and frequent local recurrence. It is currently regarded as a nonmetastasizing tumor. We describe a case of recurrent aggressive angiomyxoma with invasion into the veins including the inferior vena cava and the right atrium and with pulmonary metastases. Our case, together with those unusual cases documented in previous reports, may lead to a reappraisal of the nature of aggressive angiomyxoma.

Keywords: Aggressive angiomyxoma, Computed tomography, Inferior vena cava, Pulmonary metastases, Histopathology

INTRODUCTION

Aggressive angiomyxomas are uncommon mesenchymal tumors that predominantly involve the pelvis and perineum of young females. The characteristic feature of this tumor include frequent local recurrence and it is currently regarded as a nonmetastasizing tumor (1, 2). We present a case of a recurrent aggressive angiomyxoma with invasion of the veins along the inferior vena cava to the right atrium accompanied by pulmonary metastases. A review of the world literature reveals no previous description of aggressive angiomyxoma with invasion of the inferior vena cava and only two reports presenting metastasizing aggressive angiomyxoma (3, 4). The informed consent for the report was received from the patient and department for scientific research in our hospital.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old woman who visited our hospital presented with a 3-month history of abdominal pain and bilateral leg edema. She underwent a physical examination and a large palpable abdominal mass was discovered in the middle and lower abdomen. In other hospitals, she had undergone her first operation for pelvic tumor 10 years earlier and another operation for local relapse of the tumor six years earlier. The postoperative diagnosis was unknown because the previous medical records were unavailable. According to the statement of the patient, she had her uterus and bilateral ovaries removed in the second operation because the recurrent tumor had invaded them.

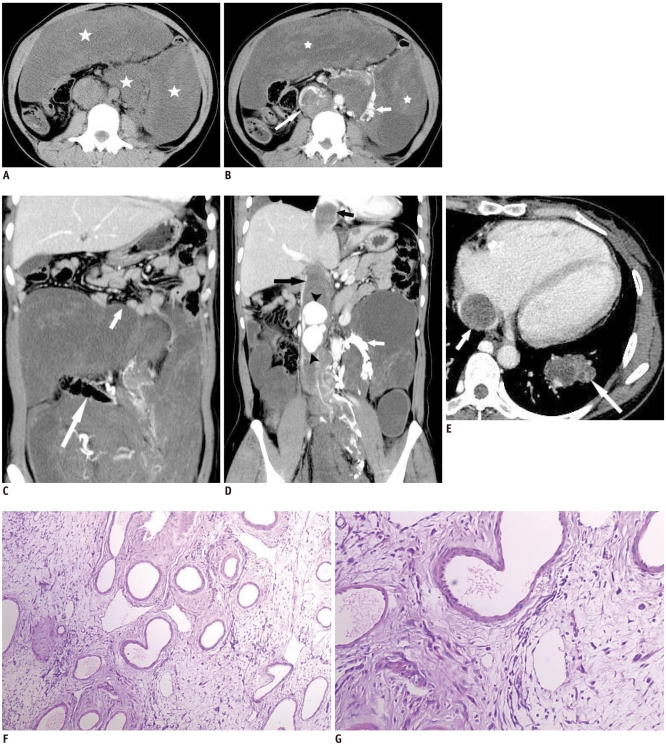

A computed tomographic (CT) examination of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed before and after the administration of intravenous contrast material. Sagittal and coronal reformatted images were produced. The results demonstrated a bulky intra- and extraperitoneal mass. The mass caused a portion of the loop of the small bowel to deviate superiorly, encase the ureters and colon, and invade the inferior vena cava (Fig. 1A-C). On unenhanced images, the mass was hypo-attenuated in relation to the surrounding muscular tissue (Fig. 1A). The mass displayed heterogeneous moderate enhancement following contrast material administration (Fig. 1B). The contrast-enhanced images depicted dilation of the inferior vena cava. A continuous tubular filling defect projected within the lumen of the inferior vena cava and extended superiorly to the level of the right atrium (Fig. 1D, E). The tubular filling defect within the lumen of the inferior vena cava had a visualized transverse diameter of 3.5 cm. There were intensely enhancing nodules within the dilated inferior vena cava and enhancing collateral vessels around the aorta during contrast-enhanced arterial and late phases (Fig. 1B, D). Contrast-enhanced thoracic CT showed multiple heterogeneously enhancing nodules and masses of different sizes in both lungs. The largest one measured 4.2 × 3.1 cm and was located in the left lower lobe (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Aggressive angiomyxoma in 37-year-old woman.

A. Unenhanced CT image shows large abdominal mass (stars) being hypo-attenuated in relation to surrounding muscular tissue. B. Contrast-enhanced CT image shows large homogeneous abdominal mass (stars). It directly invades inferior vena cava (long arrow), causing obstruction of inferior vena cava and formation of periaortic venous collaterals (short arrow). C. Coronal reconstruction image from contrast-enhanced CT shows mass encasing colon (long arrow) and causing portion of loop of small bowel to deviate superiorly (short arrow). D. Coronal reconstruction image from contrast-enhanced CT shows inferior vena cava filling defect (long black arrow) extending superiorly to level of right atrium (short black arrow). Image also shows prominent enhancing nodules within inferior vena cava (black arrowheads) and collateral vessels around aorta (white arrow). E. Contrast-enhanced CT image shows heterogeneously enhancing mass in left lower lobe (long arrow) and apparent inferior vena cava filling defect (short arrow). F. Low-power view shows vascular appearance of tumor, against myxoid, hypocellular background. G. Medium-power view shows bland cytological appearance of spindle cells.

Surgery was performed for palliative purposes to relieve the patient's symptoms. A combined operation to remove the intravascular and abdominal lesions was planned by the cardiosurgery and general surgery departments. Resection of the intracardiac and intravascular lesion through a sternotomy under total circulatory arrest and hypothermia was successfully performed, but the giant bulky intra- and extraperitoneal mass was excised incompletely because the tumor had encased the ureters, urinary bladder and colon. Histological examination of the specimen revealed a hypocellular mesenchymal lesion characterized by spindled and stellate cells with an ill-defined cytoplasm, loosely scattered in a myxoid stroma without evidence of nuclear atypia and mitosis. The lesion showed numerous, thin-to-thick wall vessels of different sizes (Fig. 1F, G). Immunohistochemical studies showed strong staining for desmin, estrogen receptors, and progesterone receptors. Staining for actin, CD34 and smooth muscle actin was intermediate, and staining for S-100 protein was negative. Based on the morphological and immunohistochemical findings as well as the patient's medical history, the diagnosis of recurrent aggressive angiomyxoma was made. Histologic examination of a specimen from a CT-guided, core needle punch biopsy of one of the pulmonary lesions showed the same histologic pattern as the abdominal mass, confirming the metastatic spread of the primary tumor.

DISCUSSION

Originally described by Steeper and Rosai (5) in 1983, an aggressive angiomyxoma is an uncommon mesenchymal tumor. It characteristically grows slowly and insidiously and carries a high risk of local relapse. The majority of these tumors occur in the pelvis and perineum of pre-menopausal women. Less commonly, the buttocks, retroperioneum, and inguinal may be implicated (6). Aggressive angiomyxoma is regarded as an aggressive neoplasm because of its propensity to recur locally. The recurrence rate has been reported to be as high as 70%, and most of these arise within two years but may occur as early as a few months or as late as 20 years (7, 8).

An aggressive angiomyxoma tends to displace adjacent organs without invading them, but the locally infiltrative nature of this tumor seems to finally lead to the invasion of adjacent organs during longstanding growth, to bulky tumor replacing the abdominal and pelvic cavity. This invasion of adjacent structures was seen in our case. On CT, the tumor encased the ureters and colon, and caused a portion of the loop of the small bowel to deviate superiorly. What is more, the tumor directly invaded the veins along the inferior vena cava to the right atrium, causing obstruction of the inferior vena cava and formation of collateral vessels. We also observed intensely enhancing nodules within the dilated inferior vena cava, which filled with tumor thrombus. We speculated this finding may be the result of arteriovenous fistulas due to tumor involvement of the inferior vena cava because the CT density of the intensely enhancing nodules was similar to that of aorta on contrast-enhanced arterial and late phase. Dilated arterial structures such as hypervascular feeding arteries and arterial aneurysm can show the similar nodular enhancement, but they would not be taken into consideration in view of the intensely enhancing nodules located within the dilated inferior vena cava.

In spite of the benign nature of this neoplasm suggested by the histology, two cases of distant metastasis were documented in previous reports. In one case, a 63-year-old woman with massive bilateral pulmonary, mediastinal, iliac, and aortic lymph node and peritoneal metastases was described by Siassi et al. (3). A second case was a young woman with multiple local recurrences and metastases in the lungs (4). We herein describe another recurrent aggressive angiomyxoma with pulmonary metastases. Despite the pulmonary metastases, the patient did not have respiratory system symptoms when hospitalized. The pulmonary metastases occurred after the second recurrence of the tumor around 10 years later, which is similar to the second case reported by Blandamura et al. (4). The pulmonary bulkiness of the tumor is smaller than that in the previous reports. The present and previously reported cases may change the current concept of aggressive angiomyxoma as a nonmetastasizing tumor. This suggests that an aggressive angiomyxoma can no longer be considered a purely localized disease. It may act in a malignant fashion and produce benign metastases in a small percentage of cases.

Aggressive angiomyxomas usually present as a well-defined homogeneous mass that is hypodense relative to muscle on unenhanced CT scanning. This is likely due to the tumor's high water content and loose myxoid matrix (9). The tumor shows moderate enhancement following intravenous contrast administration, which is related to its inherent vascularity (9). The recurrent tumor showed in the present case had a similar appearance to the primary lesion reported before.

Aggressive angiomyxomas should be distinguished from other neoplasms of the pelvic tissues such as myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma and myxoid smooth muscle neoplasm. Preoperative misdiagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma is not infrequent because of the rarity, the absence of universally typical, and the non-specific imaging appearance of these tumors.

In summary, an aggressive angiomyxoma is an uncommon mesenchymal myxoid tumor. It is characterized by frequent local recurrence and is currently regarded as a nonmetastasizing tumor. However, the recurrent tumor in the present case not only invaded the colon, ureters and inferior vena cava but also caused metastases in both lungs. Our case, together with those unusual cases documented in previous reports, may lead to a reappraisal of the nature of aggressive angiomyxomas. This suggests aggressive angiomyxomas can be, in a small percentage of cases, regarded as tumors of intermediate malignancy having an unpredictable and even sometimes unfavorable outcome.

References

- 1.Sereda D, Sauthier P, Hadjeres R, Funaro D. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: a case report and review of the literature. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2009;13:46–50. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318180436f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suleiman M, Duc C, Ritz S, Bieri S. Pelvic excision of large aggressive angiomyxoma in a woman: irradiation for recurrent disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl 1):356–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siassi RM, Papadopoulos T, Matzel KE. Metastasizing aggressive angiomyxoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1772. doi: 10.1056/nejm199912023412315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blandamura S, Cruz J, Faure Vergara L, Machado Puerto I, Ninfo V. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a second case of metastasis with patient's death. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1072–1074. doi: 10.1053/s0046-8177(03)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steeper TA, Rosai J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:463–475. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur A, Makhija PS, Vallikad E, Padmashree V, Indira HS. Multifocal aggressive angiomyxoma: a case report. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:798–799. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.10.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behranwala KA, Latifaj B, Blake P, Barton DP, Shepherd JH, Thomas JM. Vulvar soft tissue tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.14946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribaldone R, Piantanida P, Surico D, Boldorini R, Colombo N, Surico N. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:724–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heffernan EJ, Hayes MM, Alkubaidan FO, Clarkson PW, Munk PL. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the thigh. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:673–678. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]