Abstract

Objective

A randomised controlled study performed from 2007 to 2008 showed beneficial effects of a composite clinical pharmacist service as regards a simple health status instrument. The present study aimed to evaluate if the intervention was cost-effective when evaluated in a decision-theoretic model.

Design

A piggyback cost-effectiveness analysis from the healthcare perspective.

Setting

Two internal medicine wards at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden.

Participants

Of 345 patients (61% women; median age: 82 years; 181 control and 164 intervention patients), 240 patients (62% women, 82 years; 124 control and 116 intervention patients) had EuroQol-5 dimensions (EQ-5D) utility scores at baseline and at 6-month follow-up.

Outcome measures

Costs during a 6-month follow-up period in all patients and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) in patients with EQ-5D utility scores. Inpatient and outpatient care was extracted from the VEGA database. Drug costs were extracted from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. A probabilistic analysis was performed to characterise uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness model.

Results

No significant difference in costs between the randomisation groups was found; the mean total costs per individual±SD, intervention costs included, were €10 748±13 799 (intervention patients) and €10 344±14 728 (control patients) (p=0.79). For patients in the cost-effectiveness analysis, the corresponding costs were €10 912±13 999 and €9290±12 885. Intervention patients gained an additional 0.0051 QALYs (unadjusted) and 0.0035 QALYs (adjusted for baseline EQ-5D utility score). These figures result in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €316 243 per unadjusted QALY and €463 371 per adjusted QALY. The probabilistic uncertainty analysis revealed that, at a willingness-to-pay of €50 000/QALY, the probability that the intervention was cost-effective was approximately 0.2.

Conclusions

The present study reveals that an intervention designed like this one is probably not cost-effective. The study thus illustrates that the complexity of healthcare requires thorough health economics evaluations rather than simplistic interpretation of data.

Article summary

Article focus

Clinical pharmacist services have been shown beneficial for patient health and healthcare costs, although results are inconsistent. In the present article, we present combined data on costs and health outcomes for a composite clinical pharmacist service.

Key messages

Although our composite clinical pharmacist service has previously been shown beneficial as regards a simple health status instrument, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per QALY was high, more than €460 000 in the base case and more than €100 000 in most sensitivity analyses.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study is the first one to provide data on costs per QALY for an in-hospital intervention aimed to improve drug treatment. An important limitation may be that the pharmacists acted like external consultants rather than an integrated part in healthcare, and further research on cost-effectiveness of pharmacist services may be called for.

Introduction

Up to about 50% of hospital admissions are associated with drug-related problems (DRPs),1 and as a consequence, great resources are spent on such problems. When it comes to adverse drug reactions, a subset of all DRPs that constitutes about 5% of hospital admissions,2 3 only 20%–30% can be prevented.3 4 Other DRPs include inappropriate prescribing, such as failures to select the appropriate drug, route of administration, dosage or duration of treatment, based on the patient's medical history and concomitant medication. These DRPs should be possible to intervene and prevent, for example by education,5 although altering prescribing behaviour may be a difficult task. A further example of a common DRP that should be preventable is errors in patients' medication information at transitions in care.6–8 Taken together, DRPs in general need to be prevented for a rational use of drugs and an efficient utilisation of healthcare resources.

One way to achieve rational use of drugs may be through the use of clinical pharmacist services. Such services may reduce DRPs9 and increase patients' health-related quality of life.10 They may also affect the rate of readmissions to hospital, although results are inconsistent.11 12

In a randomised controlled study performed by our research group (http://clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01016301),13 we have reported positive effects of a composite in-hospital clinical pharmacist service (medication reviews, drug treatment discussion with the patient at discharge and a medication report) on self-rated health status as measured by the simple question ‘In your opinion, how is your state of health? Is it very good, rather good, neither good nor bad, rather poor or very poor?’ Health status was thus registered as an integer from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good), and at 6-month follow-up, intervention patients had better self-reported health than control patients as measured by this question (mean±SD: 3.14±0.87 vs 2.77±0.94, p=0.020).13 Clinical pharmacist services thus seem favourable for patient health. In addition, they may not cost too much, and they have even been suggested to reduce costs,11 although most economic evaluations suffer from methodological limitations.14

Taken together, the findings presented above may intuitively lead to the conclusion that in-hospital clinical pharmacist services are cost-effective. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has made an attempt to combine data on costs and health outcomes measured with the generic outcome measure quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) to calculate cost per QALY gained. Such data should be of value to healthcare decision makers, as they allow comparisons between interventions and thus facilitates prioritisation among interventions. Thus, the aim of the present study was to analyse if the composite in-hospital clinical pharmacist service in our previous study13 was cost-effective.

Methods

The study was of a ‘piggyback’ bottom–up design, in which resource use was measured in the context of a randomised controlled study primarily designed to investigate efficacy. The study was performed in two internal medicine wards at Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Mölndal situated in Region Västra Götaland in Sweden, and the details have been reported elsewhere.13 The composite intervention consisted of (1) medication reviews including feedback on prescribing to physicians; (2) drug treatment discussion with the patient at discharge and (3) a medication report including a summary of the drug treatment changes during the hospital stay and a medication list, given to the patient and sent to the patient's general practitioner (GP) at discharge. The medication reviews aimed to identify potential DRPs and did not focus on reducing costs. Patients in the control group received normal care. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before inclusion.

Costs

Costs during a 6-month follow-up period were analysed in all patients included in the randomised controlled study. In the analysis, a healthcare perspective was applied. Thus, all direct costs were included in the analysis, that is, costs for the intervention, inpatient and outpatient care and reimbursed drugs.

The costs for the intervention were estimated based on costs for working time for an in-hospital pharmacist, and time consumption for each part of the intervention was counted separately.

All healthcare consultancies during the 6-month follow-up were extracted from a regional database (VEGA database), which contain information on all inpatient and outpatient care in the Region Västra Götaland. The number of bed-days at hospital wards was extracted, as was the number of outpatient consultancies in the categories GP, specialist (including emergency department visits), nurse, and other that included all other professionals. End of follow-up was 6 months after discharge from the hospital, and only bed-days and outpatient care within this period were included in the analysis. All direct costs were estimated by combining the resource usage data with unit costs for Sweden obtained from public sources (inpatient care: €777 per bed-day; outpatient care: €144 per GP visit, €518 per specialist visit, €55 per nurse visit and €58 per visit for other professionals).

In Sweden, the majority of costs for drugs are reimbursed by the society. Costs for drugs were extracted from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, which contains individualised data on all prescribed and dispensed drugs including costs. The reimbursed costs for all drugs dispensed during the 6-month follow-up were summarised for each patient.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the intervention was estimated as gain in QALYs. Data on health-related quality of life were gathered by means of EuroQol-5 dimensions (EQ-5D) self-report questionnaires,15 which were filled in at inclusion and at 6-month follow-up. Deceased patients were assigned an EQ-5D utility score of ‘0’ at 6 months, the predefined quality-of-life weight for the health state ‘dead’ in this instrument.

For each individual, QALYs were calculated with the established area under the curve approach, that is, the change in QALY weight is assumed to occur linearly between the measurements.16 Thus, the unadjusted difference in QALYs between the randomisation groups was calculated as the mean difference between EQ-5D utility scores (6-month value minus baseline value), multiplied with the time in years (ie, 0.5) and divided with 2 (to obtain area under the curve for a triangular area). In addition, adjusted differences in QALYs were calculated since future utility scores are correlated with baseline utility scores and this may be a source of bias. Indeed, even in trials with large sample sizes, there will usually be an imbalance between arms regarding baseline utility score.17 To obtain adjusted differences in QALYs between the randomisation groups, linear regression analysis was performed to calculate the difference between EQ-5D utility score at 6-month follow-up adjusted for baseline EQ-5D utility score.17 This figure was then multiplied with 0.5 and divided with 2, as described above.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The cost-effectiveness (or, more properly, cost–utility) analysis was applied to the subset of patients where EQ-5D utility scores were available at baseline and at 6-month follow-up. All direct costs for these patients were included in the analysis, that is, costs for the intervention, inpatient and outpatient care, and reimbursed drugs.

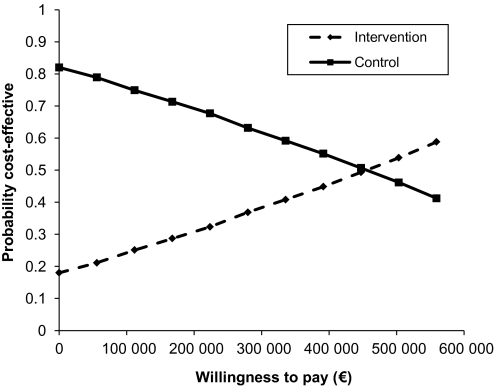

Probabilistic uncertainty analysis

A probabilistic analysis with Monte Carlo simulations was performed to characterise uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness model.18 In each simulation, parameter values were drawn randomly from the defined probability distributions. γ-Distributions were used both for costs and for (dis)utilities. The cohort of hypothetical individuals was then run through the model, and mean costs and health outcomes were calculated for both intervention and control strategies. This procedure was repeated 5000 times, generating 5000 estimates of mean costs and mean effects. The results were presented as a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, which shows the probability that the intervention was cost-effective at different levels of willingness-to-pay. The model was run in TreeAge Pro software (TreeAge Software Inc. Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA).

Sensitivity analysis

The costs for patients at the end of life are generally high, and therefore we performed a sensitivity analysis of the cost-effectiveness separately for patients alive and deceased at 6 months. Furthermore, many observations were missing for EQ-5D at 6-month follow-up. In the cost-effectiveness analysis described above, these patients were excluded. This is problematic since it means that a substantial amount of information is lost, and the results may thus be biased.19 We therefore performed a sensitivity analysis with imputed values for missing data, that is, a cost-effectiveness analysis in all 345 patients. These values were imputed in a regression model, in which we included the variables randomisation group, age, sex, EQ-5D utility scores at baseline and at 6-month follow-up and total costs. Five sets of data were created (multiple imputation) and pooled results on EQ-5D utility scores were used to estimate unadjusted and adjusted gain in QALYs.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.17.0. All costs are presented in Euro (€) (€1=8.94 Swedish crowns, €1=1.43 US dollars ($) (19 April 2011)). Student t test was used for comparisons between groups; this method is considered most appropriate for health economics analysis although skewed distribution can be expected.20 Where appropriate, values are presented both as mean±SD and median (IQR) to illustrate the skewed distribution. The study had a short time span, and costs were therefore not discounted.

Results

Costs

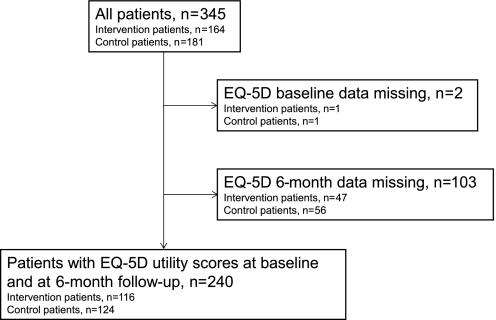

A total of 345 patients (60.9% women, 81.5 (73–85) years) were included in the analysis of costs: 181 in the intervention group and 164 in the control group (figure 1). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the randomisation groups (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population. EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 dimensions.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in the randomisation groups

| All patients |

Patients with EQ-5D utility scores at baseline and at 6-month follow-up |

|||

| Intervention (n=164) | Control (n=181) | Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=124) | |

| Age, years | 81 (72–87) | 82 (75–86) | 82 (72–87) | 82 (76–85) |

| Female sex | 98 (60) | 110 (61) | 71 (61) | 78 (63) |

| Length of stay in hospital, days | 6 (4–10) | 6 (4–10.5) | 7 (5–10.75) | 6.5 (4–11) |

| Regularly prescribed drugs at admission, n | 7 (4–9) | 7 (4–10) | 7 (4–10) | 7.5 (4.25–10) |

| Prescribed drugs as needed at admission, n | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) |

Values are presented as median (IQR) or n (%).

EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 dimensions.

The cost per work hour of a pharmacist was estimated at €66.3 assuming 1250 clinical pharmacy work hours per year and a salary of €3915 per month plus employer's fee (45% of the salary) and 20% overhead costs. The three pharmacists who performed the intervention estimated the time for each part of the intervention to 0.5 h (medication review), 0.25 h (feedback to physician), 0.20 h (patient discussion) and 1.5 h (medication report). These estimates include time for gathering information that was missing in the medical records as well as time for discussions and confirmations with the responsible physician. In all, 162 out of 164 intervention patients received medication reviews, 92 of which were fed back to the physicians, 97 patients received drug treatment discussion at discharge and 137 patients received a medication report. With these estimates and results, the costs per intervention patient were €133±41 (146 (133–163)).

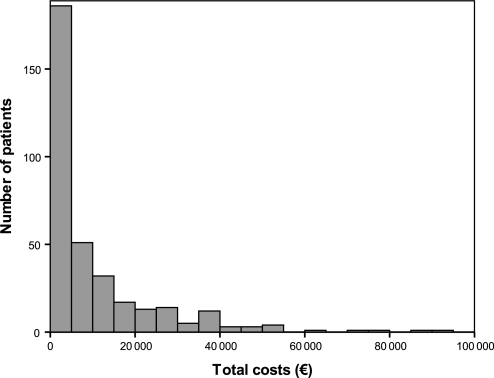

Inpatient and outpatient care during the 6-month follow-up is presented in table 2. No significant differences were found between the groups. The distribution of costs per patient is illustrated in figure 2. A total of 354 occasions of in-hospital care were identified in 171 patients during the 6-month follow-up: 173 (82 patients) and 181 (89 patients) in the intervention and the control group, respectively. A total of 4038 outpatient visits were performed by 327 patients during the 6-month follow-up: 1788 (156 patients) and 2250 (171 patients) in the intervention and the control group, respectively.

Table 2.

Inpatient and outpatient care during the 6-month follow-up

| All patients |

Patients with EQ-5D utility scores at baseline and at 6-month follow-up |

|||

| Intervention (n=164) | Control (n=181) | Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=124) | |

| Inpatient care (bed-days) | 0 (0–12.75) 10.0±16.8 | 0 (0–12) 9.4±17.8 | 1.5 (0–13.5) 10.2±17.1 | 0 (0–11.75) 8.2±15.4 |

| Outpatient care (visits) | ||||

| Total | 7 (3–16.75) 10.9±11.2 | 8 (4–14) 12.4±16.5 | 7 (3–14.5) 11.0±12.2 | 8 (4–14) 11.2±12.2 |

| GP | 1 (0–3) 1.8±2.1 | 1 (0–3) 1.8±1.9 | 1 (0–2.75) 1.8±2.0 | 2 (1–3) 1.9±1.9 |

| Specialist | 2 (1–4) 2.8±2.7 | 2 (1–4) 2.9±2.9 | 2 (1–4) 2.7±2.6 | 2 (1–4) 2.8±2.9 |

| Nurse | 1 (0–6) 4.7±8.5 | 2 (0–5) 5.7±14.3 | 1 (0–7) 4.9±9.5 | 2 (0–5) 4.5±9.5 |

| Other | 0 (0–1) 1.7±3.8 | 0 (0–2) 2.0±4.0 | 0 (0–1) 1.6±4.1 | 0 (0–2) 2.0±3.9 |

Values as presented as median (IQR) and mean±SD.

EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 dimensions; GP, general practitioner.

Figure 2.

Distribution of costs per patient.

The costs per patient for healthcare consumption and drugs during the 6-month follow-up are presented in table 3. No significant differences in costs between the randomisation groups could be detected; the total costs per patient, intervention costs included, were €10 748±13 799 (4898 (1990–14 308)) for intervention patients and €10 344±14 728 (1589 (4146–14 110)) for control patients (p=0.79).

Table 3.

Costs per individual for inpatient care, outpatient care, and reimbursed drugs during the 6-month follow-up

| All patients |

Patients with EQ-5D utility scores at baseline and at 6-month follow-up |

|||

| Intervention (n=164) | Control (n=181) | Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=124) | |

| Total | 4751 (1852–14 145) 10 615±13 795 | 4146 (1589–14 110) 10 344±14 728 | 4838 (2045–13 812) 10 776±13 995 | 3514 (1437–12 098) 9290±12 885 |

| Inpatient care | 0 (0–9907) 7756±13 037 | 0 (0–9324) 7328±13 849 | 1166 (0–10 490) 7891±13 291 | 0 (0–9130) 6398±11 958 |

| Outpatient care | 1728 (806–2863) 2041±1660 | 1786 (1011–2803) 2184±1912 | 1768 (806–3000) 1995±1579 | 1760 (987–2650) 2080±1790 |

| Reimbursed drugs | 508 (194–1006) 819±1038 | 476 (187–932) 832±1452 | 538 (223–1106) 891±1147 | 435 (159–838) 812±1610 |

Values as presented in Euro (€) as median (IQR) and mean±SD.

EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 dimensions.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that total costs for patients alive at 6 months were €9623±12 093 (4491 (1810–12 548)) for intervention patients and €9364±13 596 (3455 (1515–10 626)) for control patients. The corresponding figures for patients deceased within 6 months were €20 789±4432 (11 162 (4482–26 206)) for intervention patients and €21 504±5376 (13 186 (7941–27 622)) for control patients.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A total of 240 patients (62.1% women, 82 (75–86) years) were included in the cost-effectiveness analysis (figure 1). Six months after discharge from hospital, 38 patients were deceased: 22 and 16 in the intervention and the control group, respectively. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the randomisation groups (table 1).

EQ-5D utility scores at baseline and 6-month follow-up are presented in table 4. With these figures, the intervention patients gained an additional 0.0051 unadjusted QALYs compared with control patients. When adjusted for baseline EQ-5D, the corresponding figure was 0.0035 adjusted QALYs.

Table 4.

Health-related quality of life as measured with EQ-5D utility score

| Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=124) | |

| EQ-5D utility score | ||

| Baseline | 0.396±0.382 | 0.407±0.344 |

| 6-month follow-up | 0.385±0.362 | 0.376±0.375 |

| EQ-5D difference | −0.011±0.437 | −0.031±0.369 |

Values are presented as mean±SD.

EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 dimensions.

Inpatient and outpatient care as well as direct costs in the randomisation groups are presented in tables 2 and 3. The total costs per patient, intervention costs included, were €10 912±13 999 (4995 (2102–13 974)) and €9290±12 885 (3514 (1437–12 098)) for intervention and control patients, respectively. These figures result in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €316 243 per unadjusted QALY and €463 371 per adjusted QALY.

The probability that the intervention was cost-effective at the usual thresholds below say €50 000/QALY was approximately 0.2, which is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that 0.0063 unadjusted and 0.0091 adjusted extra QALYs were gained in intervention patients alive at 6-month follow-up. The total costs per patient were €9250±11 402 (4529 (2051–11 449)) and €7637±10 229 (2914 (1417–9928)) for intervention and control patients, respectively, resulting in €254 415 per QALY and €178 137 per adjusted QALY. The corresponding figures for deceased patients were 0.030 unadjusted QALYs gained in the intervention patients, €18 014±20 789 (11 162 (4482–26 206)) (intervention patients) and €20 448±21 504 (13 186 (7941–27 622)) (control patients), resulting in €80 601 saved per QALY in intervention patients.

Sensitivity analysis in all patients, with multiple imputation for missing data, revealed that 0.0024 unadjusted and 0.0035 adjusted extra QALYs were gained in the intervention patients, resulting in a cost of €166 566 per unadjusted QALY and €115 181 per adjusted QALY.

Discussion

The present study reveals that a composite clinical pharmacist intervention designed like this one is probably not cost-effective. This is surprising since the intervention in itself is not particularly costly and has been shown beneficial as regards a simple and understandable health status instrument.13 Moreover, we were surprised by our findings since we expected the intervention to reduce hospital visits as previously reported.11 On the contrary, our intervention seems to lead to increased healthcare costs. This coupled with a modest non-significant effect on the health outcome as measured by EQ-5D, which may be a less sensitive health status instrument than a simple health state question, leads to high costs per QALY gained. The study thus illustrates that the complexity of healthcare requires thorough health economics evaluations on joint distribution of differences in costs and effects rather than simplistic interpretation of data, and choice of outcome measures may affect the results.

There may be several explanations for our findings. First, our study was performed in a pharmacist-naive setting with relatively inexperienced pharmacists. This study setting holds the advantage that it gives a realistic picture on what to expect when introducing pharmacists as external consultants in hospital wards, information which ought to be of value for healthcare decision makers. It also enables a control group that receives normal care; this may be more difficult in settings where clinical pharmacist services are already available. On the other hand, the study setting does not allow time for the new profession to integrate in the healthcare, and this may have negatively affected the results. Thus, our results do not necessarily apply to established clinical pharmacist services, and we encourage further studies to investigate the cost-effectiveness of such services in healthcare.

Second, the content of the clinical pharmacist service may affect the results. At one end, it could consist of a passive review of the prescribed drugs, using standard decision support systems to identify possible drug–drug and drug–patient interactions, while at the other, it might comprise an active participation in medication reconciliation and medication management decisions. Indeed, medication review alone does not affect the rate of further hospital admissions (RR (95% CI) 0.99 (0.87 to 1.14)),12 whereas the opposite has been shown for a composite clinical pharmacist service.11 In our study, we evaluated a composite clinical pharmacist intervention described in the Methods section. However, the pharmacists did not take part in the rounds, as opposed to the study by Gillespie et al,11 where favourable effects of a composite clinical pharmacist intervention were reported. When designing our intervention, we considered attending the rounds too time-consuming for the pharmacists, and therefore we chose against this. Nevertheless, we believe that this decision may have negatively affected the results since it may have delayed the integration of the new profession in healthcare, and further research on pharmacist services designed differently from ours may therefore be needed. Moreover, the extent of implementation of the separate parts of our intervention varied, and it would be of value to further explore if specific parts of pharmacist interventions are cost-effective. Indeed, it has recently been pointed out in a Cochrane review that heterogeneity in study comparison groups, outcomes and measures makes it difficult to draw generalised conclusions on effects of pharmacist interventions.21

Third, estimates of costs may influence the results. In our study, the use of healthcare resources was measured under real-world conditions as is often recommended22; costs were not protocol-driven, and only costs after discharge were included, that is, after the intervention was concluded. In addition, costs were evaluated in a comprehensive manner from a healthcare perspective; we included costs for bed-days, outpatient consultancies and reimbursed drugs. When only number of hospital visits at a single hospital is included in the analysis as in the study by Gillespie et al,11 costs may be underestimated. Indeed, we found that intervention patients spent numerically more days in hospital during the 6-month follow-up period, and this may have influenced the results since in-hospital care is expensive as compared with outpatient care. One may speculate that an intervention like ours, which aim to increase patient and health professional awareness on health matters such as drug treatment and adverse reactions, may increase consumption of healthcare.

Fourth, length of follow-up may affect the results. A short-term increase in healthcare utilisation may, for example, lead to lower utilisation in the long term. We chose a 6-month follow-up since we believed that the benefits of the intervention would accrue within this time span. Changes in prescribed drugs often occur at healthcare consultancies and we expected the patient group to have many healthcare consultancies. Thus, the effects of the intervention would diminish by time, and we considered 6 months an appropriate length of follow-up. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that this choice may have affected the results, for example, by affecting long-term QALY gain, and we encourage further studies with longer follow-up periods.

More patients in the intervention group died before 6-month follow-up. We cannot present a plausible explanation for these unexpected figures since one would expect that a higher quality in prescribed drugs, an increased awareness of drugs in patients and an improved communication of drug treatment between hospital and primary care would be favourable. One may speculate, however, that the pharmacist intervention resulted in patients being either taken off medication that they would benefit from or that doses were reduced below the clinically optimal level in an effort to reduce harmful side effects or drug interactions. However, few changes in prescribed drugs were made due to the first part of the intervention, that is, the pharmacist recommendations on modifications in drug therapy,13 and we deem these unlikely to have had a major impact on patient health. Probably, the observed difference in deaths occurred by chance, but irrespective of the causality of the deaths, these negatively affected the number of QALYs gained in the intervention group.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that the pharmacist intervention may be cost saving for terminal patients. These results raise the hypothesis that clinical pharmacist interventions could be cost-effective for subgroups of patients, for example, those who cost most. Indeed, interventions targeting such patients may have great implications on healthcare costs; the majority of healthcare resources are spent on a small proportion of all patients,23 a fact that is also illustrated by the skewed distribution of costs in the present study.

An important limitation of the present study is the high degree of exclusion of patients as described in the original paper; 66% of patients admitted to the wards were deemed ineligible for inclusion by the ward physician or nurse since the design of the study required patients to be capable of discussing drug treatment and assessing their health status.13 This may make the results less applicable to a general patient population. On the other hand, this exclusion criterion may make the results more naturalistic; before a pharmacist approaches a patient, it would seem natural to ask the ward personnel if the patient is appropriate to intervene. Furthermore, EQ-5D values were not available for all patients, and analysis on patients with complete data only may have introduced bias.19 However, when imputing values for these patients in a sensitivity analysis, the cost per QALY gained was still high.

In addition, the in-hospital setting of our intervention may be questioned since the majority of prescribing decisions occur in outpatient settings. However, our choice of setting was based on several assumptions: (1) in Sweden, patients are hospitalised only if really ill, and thus we regarded such patients to be at high risk of DRPs and likely to benefit from the intervention; (2) we considered transition from inpatient to outpatient settings a major area of concern, and (3) a hospital setting provided a more practical means to implement an intervention than an outpatient setting. Indeed, a low probability of cost-effectiveness has been shown for medication reviews in an outpatient setting.24

Another limitation of the present study is that no significant differences in costs could be found. However, very large sample sizes would be required to obtain p values <0.05 since the distribution of costs is skewed. Health economists therefore advocate that the likelihood that the intervention is cost-effective should be assessed,22 as done in the present study, shown in the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

A further limitation is that a cost-effectiveness analysis from a healthcare perspective does not include costs for productivity loss. Indeed, 17 intervention patients and 24 control patients were <65 years of age,13 and an analysis of cost-effectiveness from a societal perspective may thus differ somewhat from the present results. However, we believe that a healthcare perspective is most relevant for a hospital-based intervention like this one. Furthermore, this perspective probably includes the majority of costs and benefits associated with the intervention, and we believe that a societal perspective would have led to quite similar results, particularly since the majority of patients were very old and do thus not have any productivity loss.

Conclusions

The present study reveals that a composite clinical pharmacist intervention designed like this one, when applied to a relatively heterogeneous population of predominantly older patients, is probably not cost-effective. This is surprising since the intervention is not costly and has been shown beneficial as regards a simple and understandable health status instrument, and we even expected the intervention to save costs from a healthcare perspective. The study thus illustrates that the complexity of healthcare requires thorough health economics evaluations rather than simplistic interpretation of data. Healthcare decision makers may find the results of interest when considering if and how to introduce pharmacist services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ellinor Ottosson, John Karlsson, and Lars Klintberg, who took part in the original study, as well as the personnel in the participating wards.

Footnotes

To cite: Wallerstedt SM, Bladh L, Ramsberg J. A cost-effectiveness analysis of an in-hospital clinical pharmacist service. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000329. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000329

Funding: The study was supported by the National Board of Health and Welfare. The funder played no role in the study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Göteborg, Sweden.

Contributors: All authors conceived the study. LB carried out the acquisition of patient data. SMW extracted register data. SMW and JR designed the health economics analyses, and all authors interpreted the results. SMW drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript. The researchers had access to all data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Leendertse AJ, Visser D, Egberts AC, et al. The relationship between study characteristics and the prevalence of medication-related hospitalizations: a literature review and novel analysis. Drug Saf 2010;33:233–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muehlberger N, Schneeweiss S, Hasford J. Adverse drug reaction monitoring–cost and benefit considerations. Part I: frequency of adverse drug reactions causing hospital admissions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997;6(Suppl 3):S71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rottenkolber D, Schmiedl S, Rottenkolber M, et al. Adverse drug reactions in Germany: direct costs of internal medicine hospitalizations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:626–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goettler M, Schneeweiss S, Hasford J. Adverse drug reaction monitoring–cost and benefit considerations. Part II: cost and preventability of adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admission. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997;6(Suppl 3):S79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glintborg B, Andersen SE, Dalhoff K. Insufficient communication about medication use at the interface between hospital and primary care. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:34–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Midlov P, Bergkvist A, Bondesson A, et al. Medication errors when transferring elderly patients between primary health care and hospital care. Pharm World Sci 2005;27:116–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Midlov P, Holmdahl L, Eriksson T, et al. Medication report reduces number of medication errors when elderly patients are discharged from hospital. Pharm World Sci 2008;30:92–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:955–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickard AS, Hung SY. An update on evidence of clinical pharmacy services' impact on health-related quality of life. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1623–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, et al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L, et al. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:303–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bladh L, Ottosson E, Karlsson J, et al. Effects of a clinical pharmacist service on health-related quality of life and prescribing of drugs: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:738–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Rijdt T, Willems L, Simoens S. Economic effects of clinical pharmacy interventions: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2008;65:1161–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coons SJ, Rao S, Keininger DL, et al. A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. Pharmacoeconomics 2000;17:13–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Billingham LJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Methods for the analysis of quality-of-life and survival data in health technology assessment. Health Technol Assess 1999;3:1–152 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ 2005;14:487–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claxton K. Exploring uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:781–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ 2000;320:1197–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, et al. Effect of outpatient pharmacists' non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(7):CD000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrou S, Gray A. Economic evaluation alongside randomised controlled trials: design, conduct, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2011;342:d1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berk ML, Monheit AC. The concentration of health care expenditures, revisited. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacini M, Smith RD, Wilson EC, et al. Home-based medication review in older people: is it cost effective? Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:171–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.