Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the impact of early sexual debut on HIV seroprevalence and incidence rates among a cohort of women.

Design

Prospective study.

Setting

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Participants

A total of 3492 sexually active women who consented to screen a HIV prevention trial during September 2002 to September 2005; a total of 1485 of them were followed for approximately 24 months.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

HIV seroprevalence among those who were screened for the trial and HIV seroconversion among those who seroconverted during the study.

Results

Lowest quintiles of age at sexual debut, less than high school education, a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and lack of cohabitation, being diagnosed as having herpes simplex virus 2 and other sexually transmitted infections were all significantly associated with prevalent HIV infection in multivariate analysis. During follow-up, 148 (6.8 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 5.8 to 8.0) women seroconverted. Highest seroconversion rate was observed among women who had reported to have had sex 15 years or younger (12.0 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 8.0 to 18.0). Overall, impact of risk factors considered in this study was associated with considerable potential reductions in HIV prevalence and incidence rates (population attributable risk: 85%, 95% CI 84% to 87% and population attributable risk: 77%, 95% CI 72% to 82%, respectively).

Conclusions

The association of HIV status with younger age at sexual debut may likely due to an increased number of lifetime partners. This increase could result from longer duration of sexual life. Prevention of HIV infection should include efforts to delay age at first sex in young women.

Trial registration number

Article summary

Article focus

Early sexual debut may increase women's vulnerability to HIV infection.

Early sexual debut has been associated with increased sexual risk-taking behaviour, such as having multiple partners.

Delaying sexual debut may have been one of the key changes in behaviour, which lead to a decline in HIV infection in the past.

Key messages

Our results showed that women who initiated sexual activity early were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviours.

A clear trend observed indicating that early onset sexual activity was associated with increased HIV seroprevalence and incidence.

Comprehensive sexual education programmes should reach out-of-school youth, who may be at heightened vulnerability, should be identified as well.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We cannot rule out the effects of unmeasured characteristics such as multiple or concurrent sex partners and commercial sex on our findings. No data concerning migration, socioeconomic status at the time of sexual debut or sexual behaviour data from male partners.

Nevertheless, current study used the data from the region where the HIV epidemic is severely high among particularly young women.

Introduction

Forty per cent of all adult women living with HIV reside in southern Africa.1 In many Southern African countries, >30% of young women are infected with HIV.2 3 Adolescent and young women may be especially prone to HIV infection in comparison with older women due to the occurrence of larger areas of cervical ectopy in young women and an increased likelihood of trauma to the immature genital tract during sex.4 5 Early age at sexual debut has been shown to correlate with subsequent risky sexual behaviours.6 7

Early sexual debut (commonly defined as having had first sexual intercourse at or before age 14) and experience of sexual coercion or violence have been reported to contribute unintended adolescent pregnancy.8 9 In South Africa, data from a nationally representative household survey of young people showed that 7.8% of women aged 15–24 years had had sexual intercourse by age 14, and risk of HIV infection was significantly raised if a woman had been sexually active for >12 months at the time of the survey.2

Age at first sex is an important indicator of sexual risk, as it can be used as a proxy for the onset of exposure to HIV infection.10 Early sexual debut has been associated with increased sexual risk-taking behaviour, such as having multiple partners and decreased contraceptive and condom use, and with incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).7 11 Another study has shown an association between having sex at an early age and incidence of HIV infection in Malawi.12 Delaying sexual debut may have been one of the key changes in behaviour, which lead to a decline in HIV infection in Uganda.13 14

There is also particular interest in the role of schooling in sexual risk behaviours.10 15 The association between level of schooling completed and sexual debut is complex. Although a woman's level of education may be an indicator of socioeconomic status, poor socioeconomic conditions limiting school access or contributing to poor performance may also correlate with an increase in sexual activity at an early age. In Tanzania, an analysis of the relationship between education level and HIV prevalence has indicated a steep decline over time in HIV infection among people who had a secondary education; of particular interest, the lowest HIV prevalence was found in young women (15–24 years) who had attended secondary school.16 Earlier meta-analysis of education and HIV prevalence data from across sub-Saharan Africa showed that the relationship between education and risk of HIV infection has changed over time, with more educated individuals initially at higher risk and with a later shift of risk towards the less educated, the inflection point being around 1996.17

In an attempt to better understand the risk factors that may increase South African women's risk of HIV infection, we investigated the independent risk factors and their population level impact on HIV infection among sexually active women in rural and semi-rural neighbourhoods of Durban. A sub-analysis was performed to investigate the association between the age at sexual debut and HIV seroconversion during the study by including only women who were HIV seronegative at the screening and enrolled in the study.

Methods

Study population

A total of 3492 sexually active women who consented to screening for Methods for Improving Reproductive Health in Africa (MIRA) trial of the diaphragm for HIV prevention18 (September 2002 to September 2005; undertaken in Umkomaas and Botha's Hill, southern Durban) were included in this study. The MIRA study was a randomised, controlled open-label study comparing the effectiveness of the latex diaphragm plus lubricant gel with provision of condoms alone for prevention of heterosexual HIV acquisition among women. The methodology for the MIRA study has previously been published.18 Eligibility criteria included being sexually active (defined as average of four sexual acts per month), between 18 and 49 years old, HIV negative, chlamydia and gonorrhoea negative at the screening visit (or willing to be treated if positive), not pregnant and willing to follow the study protocol requirements. All women provided written informed consent at screening.

Study procedures

At screening, an interviewer-administered questionnaire covering topics on demographics and sexual behaviour was undertaken. Participants were also offered HIV pre-test counselling before HIV and STI testing at the screening visit. HIV diagnostic testing was accomplished using two rapid tests on whole blood from either finger prick or venipuncture: determine HIV-1/2 (Abbott Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) and Oraquick (Orasure Technologies, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA). Those found to be HIV infected were referred to appropriate referral clinics for HIV care. A urine specimen was collected for testing for gonorrhoea, chlamydia and Trichomonas vaginalis infections and a blood specimen for syphilis and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2) testing. STI testing was completed using the following methodologies: chlamydia and gonorrhoea were assessed using PCR (Roche Pharmaceuticals, Branchburg, New Jersey, USA), syphilis by rapid plasma reagin in combination with Treponema pallidum haemagglutination (Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, UK), HSV2 by ELISA (FOCUS Diagnostics, Cypress, California, USA) and T vaginalis by PCR (Roche Pharmaceuticals).

At the enrolment visit, participants provided written informed consent, underwent a pelvic examination, provided a blood sample for testing for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin and T pallidum haemagglutinin; Randox Laboratories) and HSV2 (ELISA; FOCUS Diagnostics) and provided a urine sample for pregnancy testing. After enrolment, at each quarterly follow-up visit, HIV and STI testing were conducted.

The MIRA study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of California at San Francisco Institutional Review Board Committee on Human Research. The study received ethical approval from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, as well as the ethics review committees at all other local institutions and collaborating organisations. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00121459.

Measurements

The primary outcomes were proportion of women who tested positive for HIV infection at the screening visit and time to seroconversion among those who tested negative for HIV infection and enrolled in the study. Among covariates under consideration: age at the screening (<25, 25–34, 35+), age at sexual debut (in quintiles: <15, 15–16, 17–18, 19–20 and 21 years or older), education level <12 years (less than high school), language spoken at home (English vs others), religion (Christian vs other), cohabitation status (single/not cohabitating vs married/cohabiting), ever had vaginal sex using condom (yes/no), using any contraception (yes/no), diagnosed as having HSV2 and other STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis or T vaginalis). Current study only used the available data.

Statistical analyses

We expressed descriptive data as percentages, medians and IQR. The χ2 test for trend (categorical variables) and Kruskal–Wallis test (continuous variables) were used to formally compare the risk factors across the quintiles of age at sexual debut.

We examined the individual associations of the risk factors described above using univariate logistic regression, taking the HIV serostatus as the primary outcome. Next, marginally significant variables with p<0.10 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis. Variables with p<0.05 were retained in the final multivariate logistic model in a forward stepwise manner. We also tested for interactions at p<0.10 for entry into the model. Finally, to test the fitness of the model, we performed the goodness of fit test examined using the Hosmer–Lemeshow criteria. A low χ2 value and a high non-significant p value for the Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated that the fit of the model and observed values was acceptable.

The incidence rate for HIV infection, expressed as time to seroconversion, was estimated for women who were HIV negative at screening and satisfied the eligibility criteria. The date of seroconversion was estimated using the midpoint between the last negative and the first positive antibody test results within the follow-up period. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were carried out to estimate the crude HIV incidence rate over time; results were stratified and compared by the five age groups of sexual debut. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to calculate unadjusted and adjusted HIV incidence rates.

All analyses were performed using Stata V.10.0 (College Station) and SAS V.9.2.

Population attributable risk

Although ORs and RRs may be well suited to assessment of causality, they do not provide information about the potential impact on disease occurrence by eliminating these risk factors. The population attributable risk (PAR) provides additional information to determine the public health implications of risk factor reduction/elimination at population level. Briefly, we estimated PARs associated with modifiable (at least theoretically) and their 95% CI to estimate the population-level impact of the risk factors associated with HIV seroprevalence and incidence.19 We estimated that the proportion of HIV seroprevalence and incidence cases could be attributed to the combined effect of these risk factors.

Results

A total of 3492 women consented to be screened for the MIRA trial from Durban clinical research sites. The median age was 26 (IQR: 22–33), and the majority of women (96%) reported speaking Zulu at home. Only 26% of the women had completed 12 years of schooling. Approximately 86% were either single or not living with their sexual partners. The median age at sexual debut was 17 (IQR: 16–18) (data not shown). Overall prevalence of HIV infection, STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis or T vaginalis) and HSV2 were 41%, 16% and 73%, respectively.

HIV seroprevalence and other characteristics of women by quintiles of age at sexual debut

Table 1 presents the distribution of various demographic characteristics, sexual behaviours and biological risk factors according to the quintiles of age at sexual debut. Compared with the highest two quintiles, women in the lowest three quintiles were younger (p<0.001). Significant associations were found between age at sexual debut and key sexual risk behaviours. There was a linear decreasing trend observed between the proportion of women who had less than high school education and age at first sex (Ptrend<0.001). For example, compared with the oldest age at first sexual debut (>20 years), those women in the earliest age at first sexual debut quintile (<15 years) were less likely to have completed high school (62% vs 86%, Ptrend<0.001). Women were similar in terms of religion across the quintiles of the age at first sex (Ptrend=0.827). A slightly higher proportion of women reported speaking Zulu at home in the earlier quintiles of the age at first sex compared with the higher quintiles (Ptrend=0.037). Women who initiated sexual activity at an early age were more likely to report not living with their husband or sexual partners compared with those who were older. With regard to the number of sexual partners during their lifetime, early initiators were significantly more likely to have had multiple partners over their lifetimes (having at least four lifetime sex partners, Ptrend<0.001). However, other sexual risk behaviours such as proportion of women using any contraception and condoms as their main form of contraception were similar across the quintiles (Ptrend=0.784 and Ptrend=0.347, respectively). The proportion of women who tested positive for HIV infection, STIs and HSV2 were the highest among those who had early onset sexual activity (all Ptrend<0.001).

Table 1.

Association of various socio-demographic and risk characteristics with age at first sex

| Age at first sex (quintiles) |

p Value | |||||

| 1st Quintile <15 years | 2nd Quintile 15–16 years | 3rd Quintile 17–18 years | 4th Quintile 19–20 years | 5th Quintile >20 years | ||

| Demographic factors | ||||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 27 (21–34) | 25 (20–32) | 25 (21–32) | 28 (23–34) | 30 (25–35) | <0.001* |

| Less than high school education | 86% | 76% | 71% | 67% | 62% | <0.001 |

| Zulu speaking at home | 96% | 95% | 95% | 92% | 92% | 0.037 |

| Religion—Christian | 91% | 90% | 90% | 90% | 91% | 0.827 |

| Single/not living with a regular sex partner | 88% | 89% | 87% | 85% | 81% | <0.001 |

| Sexual risk behaviours | ||||||

| Using condom (as current contraception) | 45% | 42% | 47% | 45% | 46% | 0.347 |

| Using any contraception | 77% | 77% | 77% | 80% | 78% | 0.784 |

| At least four lifetime sex partners | 39% | 29% | 25% | 18% | 14% | <0.001 |

| Biological risk factors | ||||||

| HIV prevalence | 48% | 43% | 41% | 37% | 33% | <0.001 |

| STI prevalence | 20% | 15% | 14% | 13% | 12% | <0.001 |

| HSV prevalence | 79% | 74% | 71% | 70% | 68% | <0.001 |

Kruskal–Wallis test was used.

HSV, herpes simplex virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Risk factors for HIV seropositivity

Table 2 presents univariate and multivariate logistic regression results. Age at the screening visit had an inverted U shape association with risk of HIV seropositivity: compared with the youngest group (ie, 18–25 years old), those aged 25–29 years showed increased risk (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.87) and those aged 35 years or older showed decreased risk for HIV infection. Lowest quintiles of age at sexual debut, less than high school education, a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and lack of cohabitation, being diagnosed as having HSV2 and STIs were all significantly associated with prevalent HIV infection in multivariate analysis. The p value for the interaction between the quintiles of age and education in univariate analysis was calculated to be 0.683; therefore, interaction effect between these factors in the model was not considered further. The p value for the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit was 0.416, indicating that the fit of the model and observed values were acceptable.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression: ORs and 95% CIs for HIV infection

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||

| Prevalence (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| <25 | 41 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–29 | 21 | 1.98 (1.66 to 2.38) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.23 to 1.87) | <0.001 |

| 30–34 | 16 | 1.60 (1.32 to 1.95) | <0.001 | 1.19 (0.94 to 1.50) | 0.142 |

| 35+ | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.40 to 0.63) | <0.001 | |

| Age at first sex (years) | |||||

| <15 (1st quintile) | 20 | 1.87 (1.47 to 2.36) | <0.001 | 1.96 (1.53 to 2.51) | <0.001 |

| 15–16 (2nd quintile) | 20 | 1.50 (1.17 to 1.90) | 0.001 | 1.61 (1.25 to 2.08) | <0.001 |

| 17–18 years (3rd quintile) | 20 | 1.41 (1.13 to 1.76) | 0.002 | 1.49 (1.19 to 1.87) | 0.001 |

| 19–20 (4th quintile) | 20 | 1.16 (0.87 to 1.54) | 0.316 | 1.18 (0.89 to 1.59) | 0.251 |

| 21+ (5th Quintile) | 20 | 1 | 1 | ||

| At least high school education | |||||

| Yes | 26 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 74 | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.41) | 0.010 | 1.37 (1.15 to 1.62) | <0.001 |

| English spoken at home | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 1 | – | ||

| No | 95 | 1.91 (1.53 to 2.39) | <0.001 | – | |

| Religion | |||||

| Other | 9 | 1 | |||

| Christian | 91 | 1.34 (1.06 to 1.71) | 0.015 | – | |

| Number of lifetime sex partners | |||||

| One | 25 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Two | 28 | 2.49 (2.01 to 3.10) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.37 to 2.20) | <0.001 |

| Three | 21 | 4.35 (3.47 to 5.44) | <0.001 | 2.82 (2.20 to 3.62) | <0.001 |

| Four or more | 26 | 6.65 (5.35 to 8.26) | <0.001 | 4.09 (3.20 to 5.22) | <0.001 |

| Cohabitation status | |||||

| Married/living with/a sexual partner | 15 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Not married/not living with/a sexual partner | 85 | 7.02 (5.20 to 9.47) | <0.001 | 4.32 (3.11 to 6.00) | <0.001 |

| Have you ever had vaginal sex with condom? | |||||

| No | 30 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 70 | 1.40 (1.21 to 1.63) | <0.001 | – | |

| Using any contraception* | |||||

| Yes | 78 | 1 | |||

| No | 22 | 1.36 (1.16 to 1.60) | <0.001 | – | |

| HSV diagnosis | |||||

| No | 27 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 73 | 7.20 (5.88 to 8.82) | <0.001 | 6.19 (4.98 to 7.70) | <0.001 |

| STI diagnosis† | |||||

| No | 84 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 1.34 (1.12 to 1.61) | 0.001 | 1.24 (1.02 to 1.51) | 0.038 |

Any of the following: male condom, female condom, pills, injectables, spermicides, withdrawal, long term (partner vasectomy, tubal ligation), other.

Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis or Trichomonas vaginalis.

HSV, herpes simplex virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

HIV incidence by the quintiles of age at sexual debut

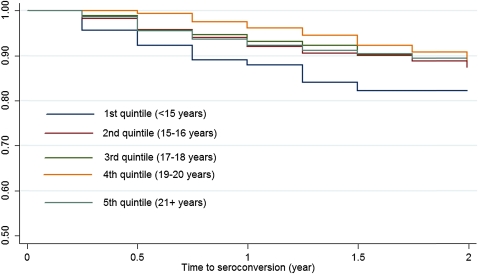

Table 2 summarises the crude incidence rate ratios and results from the Cox proportional hazard analyses unadjusted and adjusted risk. A total of 1485 women enrolled in the MIRA trial, from the Durban sites, and 148 (10.0%) HIV infections occurred during the study. Figure 1 presents the Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by the quintiles of the age at sexual debut for HIV seroconversion. The most prominent effect of age at sexual debut was observed among women who had reported to have had sex 15 years or younger compared with those who had their sexual debut after 20 years of age (12.0 per 100 person-years vs 6.4 per 100 person-years).

Figure 1.

Time to HIV seroconversion by the quintiles of age at sexual debut.

We also used unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards modelling to examine the associations between the risk of HIV seroconversion and the groups at age first sex. This analysis was not an attempt to quantify causal links for HIV seroconversion but rather to control statistically for confounding for demographic and sexual risk behaviour differences (table 3). Women who had their first sexual experience at age 15 years or younger had significantly higher risk of HIV acquisition compared with those who were 21 years or older (HR: 1.97, 95% CI 1.07 to 3.63, p=0.029). This association was slightly attenuated when the analysis was adjusted for age, level of education, number of sexual partners, cohabitation status and ever used condom with vaginal sex (HR: 1.78, 95% CI 0.96 to 3.29, p=0.066).

Table 3.

Estimated crude incidence rates and HRs for time to HIV by the quintiles of age at first sex

| Crude incidence rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age at first sex (years) | |||||

| <15 | 12.0 (8.0 to 18.0) | 1.97 (1.07 to 3.63) | 0.029 | 1.78 (0.96 to 3.29) | 0.066 |

| 15–16 | 7.2 (5.7 to 9.0) | 1.11 (0.69 to 1.80) | 0.664 | 0.90 (0.53 to 1.46) | 0.633 |

| 17–18 | 6.1 (4.1 to 9.0) | 0.95 (0.53 to 1.69) | 0.851 | 0.82 (0.45 to 1.47) | 0.496 |

| 19–20 | 5.1 (2.9 to 9.0) | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.60) | 0.503 | 0.72 (0.35 to 1.67) | 0.365 |

| 21+ | 6.4 (4.2 to 9.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

Adjusted for age, number of lifetime sex partners, cohabitation status, level of education, ever used condom with vaginal sex.

Result from PAR

Table 4 presents the proportion of HIV infections (prevalence and incidence) attributable to the independent predictors for HIV infection. Delaying age at sexual debut accounted for 26% (95% CI 21% to 31%) of the HIV infections at the screening. Completing at least high school education, 13% (95% CI 10% to 17%) of the HIV seropositivity at the screening could theoretically be prevented. Not cohabiting with a sexual partner and reporting at least four or more lifetime sexual partners accounted for 39% (95% CI 35% to 43%) and 41% (95% CI 39% to 43%) of the cases, respectively. Diagnosed as having HSV2 accounted for 82% (95% CI 80% to 83%) of the HIV cases, while STIs accounted for only 5% (95% CI 4% to 6%) of the cases. The high prevalence and high OR of HSV2 and relatively low prevalence and low OR of STIs were responsible for these impacts among women.

Table 4.

Estimated PAR (95% CI) for risk factors for the prevalence and incidence of HIV infection in the MIRA trial

| Modifiable risk factors | PAR (95% CI)* (prevalence of HIV infection) | PAR (95% CI)* (incidence of HIV infection) |

| Combined effect† | 0.85 (0.84 to 0.87) | 0.77 (0.72 to 0.82) |

| Age at first sex (<15) | 0.26 (0.21 to 0.31) | 0.17 (0.10 to 0.21) |

| Less than high school‡ | 0.13 (0.10 to 0.17) | NA§ |

| Age at first sex | ||

| + Less than high school | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.38) | – |

| Not cohabiting | 0.39 (0.35 to 0.43) | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.62) |

| Number of lifetime male sex partners | ||

| Two | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.13) | 0.11 (0.09 to 0.15) |

| Three | 0.20 (0.18 to 0.21) | 0.13 (0.11 to 0.17) |

| Four or more | 0.41 (0.39 to 0.43) | 0.16 (0.13 to 0.20) |

| Biological risk factors | ||

| Tested positive for STI¶ | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) |

| HSV2 | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.83) | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.31) |

Age adjusted.

Assumes all the risk factors removed from the target population.

Less than 12 years of education.

Level of education was not determined to be significant predictor of HIV seroconversion.

Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis or Trichomonas vaginalis at screening.

HSV2, herpes simplex virus 2; MIRA, Methods for Improving Reproductive Health in Africa; PAR, Population Attributable Risk; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

We also present estimates of the proportion of HIV incidence cases attributable to the five modifiable risk factors—namely, early age at sexual debut (<15 years), cohabitation status, number of sexual partners and diagnosed as having HSV2 and STIs. Level of education was not associated with HIV seroconversion therefore it was not included in this analysis. In the overall study population, these factors accounted for 77% (95% CI 72% to 82%) of cases. Lack of cohabitation appeared to have the largest impact on the risk of HIV seroconversion with 54% (95% CI 46% to 62%) followed by diagnosed as having HSV2 (PAR=21%, 95% CI 14% to 31%), early age at first sex (PAR=17%, 95% CI 10% to 21%) and four or more lifetime sexual partners (PAR=16%, 95% CI 13% to 20%).

Discussion

In this study of sexually active young women who initiated sexual activity early were significantly associated with prevalent HIV infection in multivariate analysis along with the other factors namely—reporting less than high school education, more than one lifetime sexual partners, single/not cohabiting with a sexual partner, diagnosed as having HSV2 and other STIs at the screening. In addition, women 25–29 years old were more likely to be infected compared with those aged <25 years. Several studies have reported associations between early onset of sexual activity and higher HIV prevalence among young people, who may not be biologically or psychologically ready for sex.20–24 In fact, increasing age at first sex appears to be one contributing factor to declines in HIV prevalence among youth in sub-Saharan countries with generalised epidemics14 25; each year of delay in sexual debut has been found to increase the chances that a condom would be used at debut by 1.44 times, which in turn increased the chances of subsequent consistent use substantially (among young men in Kenya).26 The relationship between lack of education, early sexual debut and HIV risk may be indicative of a social milieu in which young women are made vulnerable to HIV infection through interacting factors, with poverty or depressed socioeconomic status27 as one of a number of mediating forces.

A number of authors have analysed the relationship between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection, and an emerging dynamic pattern indicates that the correlation differs according to the stage of the epidemic in the country in question16 17 28 29—the highest risk shifts from populations with higher to lower educational levels as the epidemic progresses. In the South African context, in particular, recent evidence shows that higher levels of education are protective,30 in agreement with our findings.

This study is exploratory, raising questions about the dynamics of women's vulnerability and sexual risk. Lack of education may indeed be the key factor and pathway to risk among women with early sexual debut, although we could not determine the direction of the association. However, recent data from northern Malawi appear to indicate that early sexual debut may lead to school dropout since girls were viewed as ‘ready for marriage’.6

Our results also showed that women who initiated sexual activity early were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviours and a clear trend emerged, indicating that early onset sexual activity was associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion during the study follow-up.

Overall, impact of risk factors considered in this study was associated with considerable potential reductions in HIV prevalence and incidence rates (85% and 77%, respectively). If these results are applied to the target population, majority of the HIV cases among women could potentially have been avoided by effective public health interventions, particularly measures aimed at reducing number of lifetime sexual partners by keeping couples together through changes in labour migrating patterns.

Interventions for young women should start in late primary (10–12 years old)31 or early high school (13–15 years old) to emphasise condom promotion, as well as delay in sexual activity. Reaching young women prior to sexual debut is important since it has been shown that better outcomes may be expected from programmes that establish protective behaviours, rather than attempting to change existing behaviour patterns.32 A ‘life skills orientation’ programme addressing HIV prevention education (among other needs) was intended to be fully implemented in South African high schools by 2005, and thus, the women in this study may not have directly benefited from this intervention.33

Continued assessment of the impact of the life skills orientation programme on HIV protective behaviours and especially biological outcomes among young people will be necessary for an effective tailored response to the epidemic—early research indicated that the programme had positive effects on reported condom use among adolescents in two centres in KwaZulu-Natal but that other effects were at best modest.34 Also of concern in light of this is evidence from a large-scale prevention/education programme in Tanzania, which found no effect on HIV or STI prevalence, although changes in behaviour were reported.35

Potential limitations of the study

Several limitations need to be borne in mind when considering the interpretation of our results: these data were taken from the responses of women participating in a large, randomised controlled trial. Therefore, they may have limited representativeness. We also cannot rule out the effects of unmeasured characteristics such as poverty, cultural differences, multiple or concurrent sex partners and commercial sex on our findings. No data concerning migration, socioeconomic status at the time of sexual debut or sexual behaviour data from male partners were collected or included in these analyses. We could not determine whether young women were in school at the time of sexual debut.

Current study calculated the PAR where both the odds and HRs and population prevalences were estimated from the same study population. In order to interpret a PAR as the proportion of cases caused by a risk factor and thus that could be prevented by its elimination from the target population, causality needs to be proven. When PARs are estimated for more speculative risk factors, they can be regarded as measuring potential impact on disease incidence and the potential reduction in disease incidence could be attained from their elimination were later proven to be causal.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that a theory-based, contextually appropriate HIV/sexually transmitted disease risk-reduction programme may be important in shaping the sexual behaviour of young adolescents before or at the beginning of their sexual lives. Particularly, efforts to delay sexual debut should be incorporated into comprehensive sexual education programmes and should begin early, offering age-appropriate messages over time. Comprehensive sexual education programmes are typically targeted towards youth and are predominately school based. Opportunities to reach out-of-school youth, who may be at heightened vulnerability, should be identified as well. These programmes may include messages such as reinforcing safer sex practices for young people who are already sexually active.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the MIRA trial participants, Gates Foundation and PI Dr Nancy Padian. The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, The University of New South Wales. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the institutions mentioned above.

Footnotes

To cite: Wand H, Ramjee G. The relationship between age of coital debut and HIV seroprevalence among women in Durban, South Africa: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000285. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000285

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, as well as the ethics review committees at all other local institutions and collaborating organisations.

Contributors: GR was the principal investigator of the Methods for Improving Reproductive Health in Africa from Durban clinical research sites. HW performed the statistical analysis. GR and HW interpreted and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No further data available.

References

- 1.UNAIDS Report on the Global Aids Epidemic 2010. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people's sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS 2005;19:1525–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2006. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss GB, Clemetson D, D'Costa L, et al. Association of cervical ectopy with heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: results of a study of couples in Nairobi, Kenya. J Infect Dis 1991;164:588–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombs RW, Reichelderfer PS, Landay AL. Recent observations on HIV type-1 infection in the genital tract of men and women. AIDS 2003;17:455–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynn JR, Kayuni N, Floyd S, et al. Age at menarche, schooling, and sexual debut in northern Malawi. PLoS One 2010;5:e15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg J, Magder L, Aral S. Age at first coitus a marker for risky sexual behavior in women. Sex Transm Dis 1992;19:331–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gigante DP, Victora CG, Gonçalves H, et al. Risk factors for childbearing during adolescence in a population-based birth cohort in southern Brazil (In English). Rev Panam Salud Publica 2004;16:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maharaj P, Munthree C. Coerced first sexual intercourse and selected reproductive health outcomes among young women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Biosoc Sci 2007;39:231–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet 2002;359:1896–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The relationship context of contraceptive use at first intercourse. Fam Plann Perspect 2000;32:104–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boileau C, Clark S, Bignami-Van Assche S, et al. Sexual and marital trajectories and HIV infection among ever-married women in rural Malawi. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85(Suppl 1):i27–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laga M, Schwärtlander B, Pisani E, et al. To stem HIV in Africa, prevent transmission to young women. AIDS 2001;15:931–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asiimwe-Okiror G, Opio AA, Musinguzi J, et al. Change in sexual behaviour and decline in HIV infection among young pregnant women in urban Uganda. AIDS 1997;11:1757–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jukes M, Simmons S, Bundy D. Education and vulnerability: the role of schools in protecting young women and girls from HIV in southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22(Suppl 4):S41–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hargreaves JR, Howe LD. Changes in HIV prevalence among differently educated groups in Tanzania between 2003 and 2007. AIDS 2010;24:755–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Boler T, et al. Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2008;22:403–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padian NS, van der Straten A, Ramjee G, et al. Diaphragm and lubricant gel for prevention of HIV acquisition in southern African women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:251–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wand H, Spiegelman D, Law MJ, et al. Estimating population attributable risk for hepatitis C seroconversion in injecting drug users in Australia: implications for prevention policy and planning. Addiction 2009;104:2049–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison A, Cleland J, Gouws E, et al. Early sexual debut among young men in rural South Africa: heightened vulnerability to sexual risk? Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:259–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halperin DT, Epstein H. Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa's high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet 2004;364:4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg MD, Gurvey JE, Adler N, et al. Concurrent sex partners and risk for sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents. Sex Transm Dis 1999;26:208–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drain PK, Smith JS, Hughes JP, et al. Correlates of national HIV seroprevalence: an ecologic analysis of 122 developing countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;35:407–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettifor AE, van der Straten A, Dunbar MS, et al. Early age of first sex: a risk factor for HIV infection among women in Zimbabwe. AIDS 2004;18:1435–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaba B, Pisani E, Slaymaker E, et al. Age at first sex: understanding recent trends in African demographic surveys. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80(Suppl 2):ii28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yotebieng M, Halpern CT, Mitchell EM, et al. Correlates of condom use among sexually experienced secondary-school male students in Nairobi, Kenya. SAHARA J 2009;6:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathews C, Aarø LE, Flisher AJ, et al. Predictors of early first sexual intercourse among adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. Health Educ Res 2009;24:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mmbaga EJ, Leyna GH, Mnyika KS, et al. Education attainment and the risk of HIV-1 infections in rural Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania, 1991-2005: a reversed association. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:947–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson LF, Dorrington RE, Bradshaw D, et al. The effect of educational attainment and other factors on HIV risk in South African women: results from antenatal surveillance, 2000–2005. AIDS 2009;23:1583–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bärnighausen T, Hosegood V, Timaeus IM, et al. The socioeconomic determinants of HIV incidence: evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in rural South Africa. AIDS 2007;21(Suppl 7):S29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manzini N. Sexual initiation and childbearing among adolescent girls in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Reprod Health Matters 2001;9:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallant M, Maticka-Tyndale E. School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1337–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Morison LA, et al. Explaining continued high HIV prevalence in South Africa: socioeconomic factors, HIV incidence and sexual behaviour change among a rural cohort, 2001-2004. AIDS 2007;21(Suppl 7):S39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magnani R, MacIntyre K, Karim AM, et al. The impact of life skills education on adolescent sexual risk behaviors in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:289–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyle AM, Ross DA, Maganja K, et al. Long-term biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: follow-up survey of the community-based MEMA kwa Vijana Trial. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.