Abstract

Background

The mitochondrial DNA mutation m.1555A>G predisposes to permanent idiosyncratic aminoglycoside-induced deafness that is independent of dose. Research suggests that in some families, m.1555A>G may cause non-syndromic deafness, without aminoglycoside exposure, as well as reduced hearing thresholds with age (age-related hearing loss).

Objectives

To determine whether adults with m.1555A>G have impaired hearing, a factor that would inform the cost–benefit argument for genetic testing prior to aminoglycoside administration.

Design

Population-based cohort study.

Setting

UK.

Participants

Individuals from the British 1958 birth cohort.

Measurements

Hearing thresholds at 1 and 4 kHz at age 44–45 years; m.1555A>G genotyping.

Results

19 of 7350 individuals successfully genotyped had the m.1555A>G mutation, giving a prevalence of 0.26% (95% CI 0.14% to 0.38%) or 1 in 385 (95% CI 1 in 714 to 1 in 263). There was no significant difference in hearing thresholds between those with and without the mutation. Single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis indicated that the mutation has arisen on a number of different mitochondrial haplogroups.

Limitations

No data were collected on aminoglycoside exposure. For three subjects, hearing thresholds could not be predicted because information required for modelling was missing.

Conclusions

In this cohort, hearing in those with m.1555A>G is not significantly different from the general population and appears to be preserved at least until 44–45 years of age. Unbiased ascertainment of mutation carriers provides no evidence that this mutation alone causes non-syndromic hearing impairment in the UK. The findings lend weight to arguments for genetic testing for this mutation prior to aminoglycoside administration, as hearing in susceptible individuals is expected to be preserved well into adult life. Since global use of aminoglycosides is likely to increase, development of a rapid test is a priority.

Article summary

Article focus

Individuals who have the m.1555A>G mutation are exquisitely sensitive to rapid-onset hearing loss after receiving aminoglycosides at normal therapeutic levels.

We sought to determine whether a cohort of mature individuals with the m.1555A>G mutation have hearing loss by their mid-40s because the mutation has been reported to cause later-onset less severe hearing loss in people who have never been exposed to aminoglycosides. We wished to determine whether genetic screening prior to aminoglycoside administration is justified.

Key messages

This study demonstrates the prevalence of m.1555A>G to be 1 in 385 (95% CI 1 in 714 to 1 in 263) in the 1958 British birth cohort, confirming that this mutation occurs frequently in Caucasian populations.

The hearing of individuals with the m.1555A>G mutation is no different to that of the general population at age 44–45 years, in contrast to previous reports which suggested that hearing decreases with age in people with m.1555A>G; any such effect is not large and likely to be subject to previous ascertainment bias.

These findings lend weight to the argument for genetic testing for the m.1555A>G mutation prior to aminoglycoside administration in order to prevent avoidable hearing loss.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Hearing data have been collected prospectively, which avoids some of the biases inherent in studies related to deafness and hearing loss.

A potential limitation of the study was that data on aminoglycoside exposure were not collected.

Introduction

Aminoglycosides are widely used for treatment of and prophylaxis against serious Gram-negative infections. They are used in many situations including neonatal septicaemia especially in premature babies where they are often first-line treatment, surgical prophylaxis in β-lactam-allergic patients of all ages, febrile neutropenia, septic shock and drug-resistant tuberculosis. They are well known to be ototoxic (ie, toxic to the cochlea and the vestibular system) and nephrotoxic, and therefore, drug levels are monitored to ensure that they are within recommended limits. However, one in 500 people has a maternally inherited genetic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation, termed m.1555A>G, which predisposes to extreme idiosyncratic hypersensitivity to aminoglycosides, resulting in permanent and profound deafness.1 2 In such patients, standard doses with drug levels within the therapeutic range cause severe irreversible ototoxicity.

It is also reported that m.1555A>G can cause hearing loss even in the absence of aminoglycoside exposure, although this tends to be less severe and of later onset,3 4 and that nuclear-encoded modifier genes may increase penetrance of the mutation in such cases.5 The m.1555A>G mutation has also been reported to cause age-related hearing loss: in the Blue Mountains Hearing Study, consisting of non-institutionalised permanent residents of two suburban areas west of Sydney over the age of 49, Vandebona et al6 reported that mean auditory thresholds were significantly higher in three of six carriers of m.1555A>G compared with the general population.

Aminoglycosides exert their antibacterial effects by binding to the decoding region, specifically the aminoacyl-tRNA acceptor site (or A site) of bacterial ribosomes, altering their conformation.7 This destabilises codon–anticodon pairing, resulting in codon misreading that induces errors in protein synthesis.8 In the human mitochondrion, mtDNA encodes 13 protein components of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system translated on mitochondrial ribosomes. Inaccurate mitochondrial translation may lead to errors in these proteins, resulting in inefficient OXPHOS, impaired ATP generation and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Human mitochondrial ribosomes bear a structural resemblance to bacterial ribosomes, from which they evolved, but the sequence at the decoding region in humans is different from that at the corresponding site in bacterial ribosomes and does not normally allow aminoglycoside binding. Mutation from adenine to guanine at position 1555 of the human mitochondrial 12S rRNA causes a structural rearrangement which facilitates aminoglycoside binding. The mechanism by which this mutation causes deafness is unproven but is thought to involve the generation of toxic ROS in the cochlear hair cells.9

There is an argument for genetic testing prior to aminoglycoside use, so that alternative antibiotics can be selected for those with the mutation in order to prevent lifelong deafness.1 However, cost–benefit analyses also take into account the observations that m.1555A>G may cause later onset hearing loss in the absence of aminoglycosides and that gradual hearing loss may be an inevitable consequence of the mutation.10

We wanted to ascertain hearing levels in adults with m.1555A>G in order to determine whether normal hearing is preserved into middle age, an observation that would strengthen the argument for genetic testing prior to aminoglycoside usage.

Methods

Design

We performed a population-based cohort study by genotyping 7747 DNA samples from the 1958 British birth cohort for the m.1555A>G mutation and comparing the genotype with hearing outcome at 44–45 years. We haplogrouped those who had m.1555A>G by GeneChip® resequence analysis (see below) to ensure that not all subjects belonged to a single haplogroup that might be influencing penetrance of the mutation.

Study population

The British 1958 cohort (also known as the National Child Development Study) includes all births in England, Wales and Scotland during 1 week in 1958. From an original sample of over 17 000 births, survivors were followed up at ages 7, 11, 16, 23, 33 and 42 and at 44–45 by biomedical interview and test. Immigrants of the same dates of birth were identified at ages 7, 11 and 16 and followed into adulthood, but adult immigrants (after age 16) have not been included. Data collected up to age 42 by interviews with parents and cohort members and at school medical examinations include information on growth, health and health-related behaviour, family background, socioeconomic circumstances, behavioural, emotional and cognitive development, educational achievement, employment, psychosocial work characteristics, partnership and pregnancy histories.

All eligible cohort members (ie, all except ‘permanent refusals’) were invited to participate in a clinical examination by a trained research nurse visiting their home. Following a period of piloting, this fieldwork started in September 2002 and was completed in March 2004. The visits were carried out by a team of over 120 specially trained nurses from the National Centre for Social Research, who conducted the annual Health Surveys of England and Scotland. From a target sample of 12 069 persons, 9377 cohort members were visited. Eight thousand eight hundred and ninety-four of these have a valid hearing measure at 1 and 4 kHz.

Blood samples were collected from 88% of those examined, and 97% of these gave consent to creation of immortalised cell lines and extraction and storage of DNA for medical research purposes. Eight thousand and eighteen blood samples were received from subjects who gave consent to extraction of DNA, and 7980 of these also gave consent for creation of immortalised cell cultures. More details of the DNA collection are available from the Access Committee for CLS Cohorts website (http://www2.le.ac.uk/projects/birthcohort). This study was approved by the SouthEast Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed by KBioscience (http://www.kbioscience.co.uk; protocols available on request) following successful ‘blind’ validation of the assay using known positive and negative controls. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping for m.1555A>G was performed by competitive allele PCR (KASPar) (http://www.kbioscience.co.uk/genotyping/genotyping-chemistry.htm).1 Blanks and duplicate samples were included in all plates for quality assurance purposes.

Seven thousand seven hundred and forty-seven samples were genotyped. The 19 individuals who had m.1555A>G were confirmed ‘in house’ by conventional Sanger dideoxy termination cycle sequencing to have the mutation, and haplogroups were constructed from genotypes generated by GeneChip® resequence analysis.

GeneChip® resequence analysis

The GeneChip® Human Mitochondrial Resequencing Array 2.0 (Affymetrix) was used to interrogate the entire mtDNA sequence of the 19 individuals found to carry the m.1555A>G mutation. The 16.5 kb mitochondrial genome was amplified in two fragments using the Expand Template Long PCR Kit from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

PCR primers were Mito1-2F ACATAGCACATTACAGTCAAATCCCTTCTCGTCCC, Mito1-2R ATTGCTAGGGTGGCGCTTCCAATTAGGTGC-9307, Mito3F TCATTTTTATTGCCACAACTAACCTCCTCGGACTC and Mito3R CGTGATGTCTTATTTAAGGGGAACGTGTGGGCTAT-7814. Cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step of 3 min at 94°C, followed by 10 cycles of denaturation for 10 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 60°C and extension for 10 min at 68°C; then 25 cycles of denaturation for 10 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 60°C and extension for 10 min + an additional 20 s per cycle at 68°C and a final extension step of 10 min at 68°C. Concentration of DNA in the long PCR products was determined using nanodrop spectrophotometry, and equimolar concentrations of the two PCR products were pooled. These were digested with DNAseI. Prehybridisation, hybridisation, washing and scanning of the GeneChip® were performed according to the Affymetrix CustomSeq Resequencing protocol. Sequences were analysed using GSEQ 4.2 software. SNPs were automatically called by GSEQ and presented in an SNP viewer format. Haplogroups were assigned manually by examination of key defining polymorphisms (see table 2).

Table 2.

Haplogroup prevalence in 1958 cohort

| Number of samples | Percentage | Characterising single-nucleotide polymorphisms | Haplogroup |

| 8 | 42 | 14766T, 4216T, 13708G | J |

| 6 | 32 | 14766T, 12308A, 10550G | U |

| 5 | 26 | 14766C, 7028C | H |

Pure tone audiometry at age 44–45 years

Pure tone audiometry was performed by air conduction in each ear, at frequencies of 1 and 4 kHz according to the British Society of Audiology recommended procedure. MA25 portable audiometers with TDH 49 earphones in audiocups were used, calibrated to British Standard BS EN ISO 389-1 (2000) (identical to ISO 389-1). Testing was carried out by the study research nurses, who received training from experienced audiologists.11 Only information from completed tests was used.

Statistical analysis

Hearing threshold in the better ear at two frequencies (1 and 4 kHz), transformed by log transformation (log (y+16.6) for 1 KHz and log (y+20.6) for 4 KHz) subject to difference between ears being <20 dB (at 1 and 4 kHz), was modelled by multiple regression in relation to family history of hearing loss (yes/no), diabetes (age of onset >20 years), gender, noise at work (>5, 1–5, <1 years, none) with further control for noise at test (yes/no). Those with conductive hearing loss in childhood (by proxy measures at ages 7, 11) or with profound hearing loss at ages 7 or 11 (>60 dB) were excluded. Modelling was on the non-mutation (non-carrier) data. Ninety per cent prediction intervals from this model were applied to the mutation (carrier) data and are shown transformed back to the dB scale in table 3. The model was checked at both frequencies to rule out multicollinearity, and plots of residuals against fitted values and normal plots did not reveal any heteroscedasticity or non-normality of residuals. No cases with high influence (Cook's distance) were found. Predictions from the model and 90% prediction intervals are transformed back to the raw scale.

Table 3.

Hearing data of 19 individuals carrying m.1555A>G from the 1958 birth cohort with 90% prediction intervals

| Case | At 1 kHz (dBHL) |

At 4 kHz (dBHL) |

||||||

| Observed hearing threshold | Predicted hearing threshold | Lower predicted hearing threshold (5th percentile) | Upper predicted hearing threshold (95th percentile) | Observed hearing threshold | Predicted hearing threshold | Lower predicted hearing threshold (5th percentile) | Upper predicted hearing threshold (95th percentile) | |

| 1 | 10 | – | – | – | 15 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 0 | 4.07 | −4.36 | 18.32 | 25 | 7.37 | −5.8 | 32.27 |

| 3 | 5 | 5.16 | −3.71 | 20.18 | 0 | 8.81 | −5.04 | 35 |

| 4 | 5 | 4.37 | −4.18 | 18.83 | 5 | 6.25 | −6.39 | 30.14 |

| 5 | 5 | 5.51 | −3.5 | 20.76 | −5 | 4.12 | −7.52 | 26.12 |

| 6 | 0 | 4.07 | −4.36 | 18.32 | 35 | 7.37 | −5.8 | 32.27 |

| 7 | 5 | 5.61 | −3.45 | 20.93 | 0 | 10.57 | −4.11 | 38.32 |

| 8 | 0 | 4.66 | −4 | 19.31 | 5 | 2.56 | −8.35 | 23.16 |

| 9 | −10 | 4.66 | −4 | 19.31 | 10 | 2.56 | −8.35 | 23.16 |

| 10 | 0 | 5.4 | −3.57 | 20.58 | 0 | 9.17 | −4.85 | 35.68 |

| 11 | 10 | 6.55 | −2.9 | 22.53 | 10 | 7.53 | −5.72 | 32.6 |

| 12 | 5 | 4.66 | −4 | 19.31 | 10 | 2.56 | −8.35 | 23.16 |

| 13 | 5 | 5.76 | −4 | 19.31 | 0 | 2.56 | −8.35 | 23.16 |

| 14 | 10 | – | – | – | 0 | – | – | – |

| 15 | 0 | 4.37 | −4.18 | 18.83 | 5 | 6.25 | −6.39 | 30.14 |

| 16 | 0 | 4.66 | −4 | 19.31 | 10 | 2.56 | −8.35 | 23.16 |

| 17 | 10 | 4.07 | −4.36 | 18.32 | 5 | 7.37 | −5.8 | 32.27 |

| 18 | 15 | 5.91 | −3.27 | 21.45 | 15 | 6.29 | −6.38 | 30.22 |

| 19 | 10 | – | – | – | 5 | – | – | – |

Those without predicted hearing thresholds lacked information required for modelling (missing values on one or more explanatory variables).

dBHL, decibel hearing level.

As missing values on explanatory variables resulted in only 18% of cases (1635 of 9532) with valid dependent values being lost to analysis, it was not considered necessary to use imputation or weighting methods to compensate for this.

Results

Genotyping

Genotyping using the KASPar competitive allele PCR was successful for 7350 of 7747 individuals (table 1). Of these, 19 had m.1555A>G, giving a prevalence of 0.26% (95% CI 0.14% to 0.38%) or 1 in 385 (95% CI 1 in 714 to 1 in 263). Both Sanger cycle sequence and GeneChip® resequence analyses confirmed that all 19 samples had m.1555A>G, as reported by GSEQ in SNP viewer and by manual inspection of the mock electropherograms.

Table 1.

Genotyping results for m.1555A>G

| Frequency | Valid per cent | |

| Valid A | 7331 | 99.7 |

| Valid G | 19 | 0.3 |

| Total | 7350 | 100.0 |

Haplogrouping of those with m.1555A>G was performed by GeneChip® resequence analysis to ensure that subjects did not all belong to a single haplogroup that might be influencing penetrance of the mutation. All the haplogroups found were of European ancestry, as expected in the British 1958 cohort (table 2, supplementary table 1). The most prevalent haplogroup was ‘J’ followed by ‘U’ and finally ‘H’. This haplogroup prevalence was very similar to that of the Blue Mountains cohort, in which two of five mutation carriers belonged to haplogroup ‘J’, two to ‘U’ and one to ‘H’.6

Hearing comparison with non-mutation carriers

We compared hearing thresholds in the better hearing ear at 1 and 4 kHz in those with and without the mutation. Table 3 shows hearing data of 19 individuals carrying m.1555A>G from the 1958 birth cohort with 90% prediction intervals. We found no significant difference between the two groups at age 44–45 years. One individual, subject 6, had a hearing threshold at 4 kHz that was above the 90% prediction intervals of the model and one person, subject 9, had a threshold at 1 kHz that was below.

Discussion

We have shown that 1 in 385 (95% CI 1 in 714 to 1 in 263) people in the British 1958 cohort have the m.1555A>G mutation but that at age 44–45 years their hearing is not significantly different from those without the mutation. Data on aminoglycoside exposure have not been prospectively collected in this cohort, but it is likely that no one has been exposed to this major environmental trigger and that the avoidance of aminoglycosides in susceptible people can be expected to result in normal hearing, at least until 44–45 years of age.

The normal hearing of the individuals identified in this study suggests that m.1555A>G is a susceptibility factor, requiring other environmental and/or genetic factors to result in deafness, the most common environmental interaction being aminoglycoside exposure. The frequency of m.1555A>G of 1 in 385, together with the normal hearing of mutation carriers in the 1958 birth cohort and previously in children of the ALSPAC cohort who have the mutation,1 raises the question of whether it is truly pathogenic. Both genetic and biochemical evidence support its pathogenic role. The frequency of this mutation in individuals who have become deaf following aminoglycosides is 13%–60%,12 13 a frequency far greater than that in the hearing population; and in countries such as Spain and China, where aminoglycosides are widely used, this mutation accounts for 27% of cases of familial progressive deafness.4 In addition, biological data have demonstrated defects in mitochondrial protein synthesis leading to reduced OXPHOS in cell lines from affected individuals.14–16 These defects are caused by the mtDNA mutation itself because they were transferred with mutant mtDNA when enucleated patient cells were fused with cells lacking mtDNA (ρ-zero cells) to make transmitochondrial cybrids.16

It appears that the accuracy of correct amino acid incorporation into synthetic polypeptides is reduced in the presence of m.1555A>G, and more so in the presence of aminoglycosides, thereby causing reduced biological activity of the proteins assayed.8 Construction of artificial bacterial hybrid ribosomes has demonstrated that this effect was evident at 25-fold lower concentrations of aminoglycoside compared with that observed in non-mutant ribosomes, mimicking the enhanced sensitivity of the mutation-bearing human ear to aminoglycosides.

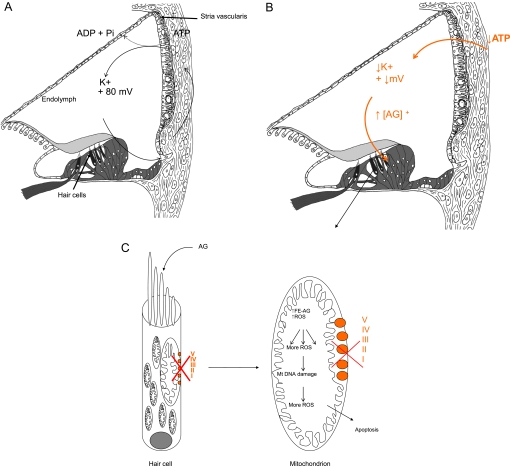

An unanswered question is why m.1555A>G appears to cause only deafness, in the absence of nephrotoxicity or other systemic effects typically seen in dose-related aminoglycoside toxicity. We hypothesise that the stria vascularis, a highly specialised metabolically active layered epithelium rich in mitochondria which lines the lateral wall of the cochlear duct, is the primary site of aminoglycoside toxicity in individuals with the m.1555A>G mutation. The stria is responsible for energy-dependent transport of ions into the endolymphatic fluid of the cochlear duct compartment. This generates a large positive extracellular potential, the endocochlear potential (EP) of +80 to 100 mV and high potassium concentration (150 mM) in the endolymph of the cochlea, necessary for auditory transduction (figure 1A). It is known that if energy-dependent ion transport is inhibited, EP falls rapidly (figure 1B) and so does hearing sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism for enhanced sensitivity of the cochlea to aminoglycosides. Aminoglycosides normally pass into the endolymph in low concentrations because the endolymph is positively charged as are aminoglycosides. They then pass into hair cells through auditory transduction channels on their apical surfaces. (A) In the presence of m.1555A>G, there is a reduction in OXPHOS in the stria vascularis, a tissue packed full of mitochondria. Decreased ATP production is hypothesised to reduce the endocochlear potential (EP) generated by the stria vascularis and to fall from its normal value of about +80 mV. The reduction in positive potential attracts more positively charged aminoglycosides into the endolymphatic compartment and then into hair cells. (B) The raised concentration of aminoglycosides in the endolymph, secondary to the fall in EP caused by inaccurate translation of OXPHOS proteins, is unique to the inner ear and may explain why it alone is so sensitive to the effects of aminoglycosides in the presence of m.1555A>G. (C) In the hair cells, the concomitant mitochondrial OXPHOS defect is associated with increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and generation of iron species (gentamicin acts as an iron chelator), causing formation of a toxic aminoglycoside–iron complex (Fe–AG). This activates molecular oxygen, which is reduced to superoxide by an electron donor such as arachidonic acid, and results in formation of other ROS in a chain reaction. These activate apoptotic cell pathways and cause hair cell death. AG, aminoglycosides; I–V represents complexes I–V of the mitochondrial OXPHOS system.

We hypothesise that when aminoglycosides bind to the decoding site of mutant mitochondrial ribosomes in the stria, the marked reduction in fidelity of translation of the OXPHOS proteins causes an energetic defect resulting in a significant reduction in EP; this then further attracts positively charged aminoglycosides into the cochlear duct where they achieve a higher concentration than usual. Because the EP is unique to the cochlea and not generated in the vestibular system, the toxic effects of m.1555A>G at ‘normal’ doses of aminoglycosides are observed only in the cochlea.17 From the endolymph, aminoglycosides then pass into the cochlear sensory hair cells through mechanotransduction channels in their apical surface, which open in response to sound. Once in the hair cells, the half-life of aminoglycosides is extremely long; animal studies have shown that aminoglycosides are detectable in cochlear hair cells for up to 6 months after administration, so increased concentration of aminoglycosides in the endolymph is likely to result in rapid accumulation, at what are considered to be ‘normal’ drug levels.18 19 Finally, the concomitant pre-existing mitochondrial OXPHOS defect within the hair cells themselves is associated with increased production of ROS and generation of iron species. The iron species bind to aminoglycosides to produce a toxic complex, which mediates cochlear cell death via apoptosis (figure 1C).

In addition to aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity, m.1555A>G has also been reported to cause non-syndromic hearing loss without aminoglycoside exposure. However, in those families, hearing loss was less severe and of later onset.3 4 It has been proposed that in such families there is an additional genetic modifier which causes hearing loss in the absence of aminoglycosides. One such modifier, the A10S variant in the gene encoding TRMU, a mitochondrial protein related to transfer RNA (tRNA) modification, was also assayed in our cohort but no one with m.1555A>G was homozygous for this variant and so we cannot assess whether hearing threshold might be influenced by this additional variant. Clearly, in the UK, both in the 1958 cohort and the ALSPAC cohort, there does not appear to be any evidence that m.1555A>G causes non-syndromic hearing loss in our population. Recently, Vandebona et al6 reported that m.1555A>G causes age-related hearing loss: mean auditory thresholds were significantly higher in three of six carriers of m.1555A>G compared with the general population. We find no such effect. However, their population was significantly older than the 1958 cohort, and we cannot exclude that those with m.1555A>G in our cohort will experience deterioration in hearing thresholds greater than would be expected for their age in later life.

Our work describes the findings in a birth cohort on whom hearing data have been collected prospectively and as a result avoids some of the biases which are inherent in studies related to deafness and hearing loss. It confirms our previous prevalence figures, and since the cohort is not a geographical one, it does not suffer from the potential confounder that all individuals with the mutation could share a common (local) ancestor. In fact, we have excluded this possibility by demonstrating that the mutation has arisen on a number of different European mitochondrial haplogroups. Nevertheless, a potential limitation of the study was that data on aminoglycoside exposure were not collected and that in three of the 19 subjects hearing thresholds could not be predicted because information required for modelling was missing. However, their measured hearing thresholds appear to be well within accepted criteria for normality. Further sources of bias could be secondary to genotyping failures, particularly if mutation carriers with raised hearing thresholds were over-represented in this group. In addition, it is possible that samples with low heteroplasmy levels may not have been detected by the KASPar genotyping method, possibly leading to an underestimate of the mutation frequency in this cohort.

Our finding of normal hearing in adults with m.1555A>G up to the age of 44–45 has considerable implications for public health globally as well as routine clinical practice. Global usage of aminoglycosides is likely to increase, particularly with the emergence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) since these are cheap antimicrobial agents with broad spectrum coverage recommended as second-line treatment for use in MDR-TB. Over half a million new cases of MDR-TB are reported per year, with a likely global prevalence of at least two to three times that figure.20 We have confirmed that m.1555A>G is common (almost 1 in 400 individuals) and showed previously that it is associated with normal hearing in childhood.1 Therefore, many people at risk of aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss are likely to have normal hearing if they have not been exposed to aminoglycosides and will not be suspected of being susceptible by any means other than genetic testing. Rapid genetic testing prior to aminoglycoside administration would be ideal in order to prevent avoidable deafness21 22 because those who have the mutation should be prescribed alternative antibiotics. Currently, all genetic screening is performed on an elective basis rather than in an acute situation because no rapid testing is available. Premature neonates pose a particular problem since they cannot be electively tested and aminoglycosides are widely used for the treatment of suspected neonatal sepsis, where they are highly effective and drug resistance is low. Developing countries are also a major concern since aminoglycoside usage is likely to increase together with MDR-TB.

In conclusion, the m.1555A>G mutation predisposing to aminoglycoside ototoxicity is prevalent in Caucasian populations, with a frequency of 1 in 385 in the 1958 British birth cohort. Reassuringly, normal hearing is maintained until 44–45 years in individuals with the mutation. This is one factor that would favour screening for this mutation prior to aminoglycoside administration to avoid preventable deafness. However, arguments around preemptive pharmacogenetic testing are often complex and based on models with missing information; we concur that further research is needed to inform the case.23

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants of the British 1958 cohort (the National Child Development Study) and all those responsible for collection of the original data.

Footnotes

To cite: Rahman S, Ecob R, Costello H, et al. Hearing in 44–45-year-olds with m.1555A>G, a genetic mutation predisposing to aminoglycoside-induced deafness: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000411. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000411

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from Sparks, the Children's Medical Research Charity and by a Summer Studentship from the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (now Action on Hearing Loss). Research at the University College London Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children National Health Service Trust benefits from R&D funding received from the National Health Service Executive. MB-G and SR are supported by Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. The researchers were independent of the funders. The organisations responsible for funding had no role in the design or conduct of the study or in collection, analysis and interpretation of data or preparation, review or approval of this manuscript. The authors had full access to all data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: SouthEast Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

Contributors: SR and MB-G were responsible for inception and design of the study, for data collation, analysis of the molecular genetic data and writing the manuscript. RE and AD were responsible for statistical analysis of the audiometric data. HC, MGS and AJD were responsible for confirmation of mutation status and GeneChip analysis, which was performed by KP. DS was responsible for data linkage and AF helped to formulate the hypothesis. All authors read and approved the final version and were involved in critical revision of the manuscript. SR and MB-G are guarantors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Complete mitochondrial DNA resequence data of all 19 individuals with the m.1555A>G mutation are attached as a supplementary file.

References

- 1.Bitner-Glindzicz M, Pembrey M, Duncan A, et al. Prevalence of mitochondrial 1555A-->G mutation in European children. N Engl J Med 2009;360:640–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchin T, Haworth I, Higashi K, et al. A molecular basis for human hypersensitivity to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Nucleic Acids Res 1993;21:4174–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prezant TR, Agapian JV, Bohlman MC, et al. Mitochondrial ribosomal RNA mutation associated with both antibiotic-induced and non-syndromic deafness. Nat Genet 1993;4:289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estivill X, Govea N, Barcelo E, et al. Familial progressive sensorineural deafness is mainly due to the mtDNA A1555G mutation and is enhanced by treatment of aminoglycosides. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan MX, Yan Q, Li X, et al. Mutation in TRMU related to transfer RNA modification modulates the phenotypic expression of the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA mutations. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:291–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandebona H, Mitchell P, Manwaring N, et al. Prevalence of mitochondrial 1555A-->G mutation in adults of European descent. N Engl J Med 2009;360:642–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortopassi G, Hutchin T. A molecular and cellular hypothesis for aminoglycoside-induced deafness. Hear Res 1994;78:27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobbie SN, Bruell CM, Akshay S, et al. Mitochondrial deafness alleles confer misreading of the genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:3244–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forge A, Schacht J. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol Neurootol 2000;5:3–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veenstra DL, Harris J, Gibson RL, et al. Pharmacogenomic testing to prevent aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss in cystic fibrosis patients: potential impact on clinical, patient, and economic outcomes. Genet Med 2007;9:695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ecob R, Sutton G, Rudnicka A, et al. Is the relation of social class to change in hearing threshold levels from childhood to middle age explained by noise, smoking, and drinking behaviour? Int J Audiol 2008;47:100–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usami S, Abe S, Akita J, et al. Prevalence of mitochondrial gene mutations among hearing impaired patients. J Med Genet 2000;37:38–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Li R, Chen J, et al. Mutational analysis of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in Chinese pediatric subjects with aminoglycoside-induced and non-syndromic hearing loss. Hum Genet 2005;117:9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan MX, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Attardi G. A biochemical basis for the inherited susceptibility to aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:1787–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan MX, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Attardi G. Nuclear background determines biochemical phenotype in the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutation. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:573–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue K, Takai D, Soejima A, et al. Mutant mtDNA at 1555 A to G in 12S rRNA gene and hypersusceptibility of mitochondrial translation to streptomycin can be co-transferred to rho 0 HeLa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;223:496–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Usami S, Abe S, Kasai M, et al. Genetic and clinical features of sensorineural hearing loss associated with the 1555 mitochondrial mutation. Laryngoscope 1997;107:483–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gale JE, Marcotti W, Kennedy HJ, et al. FM1–43 dye behaves as a permeant blocker of the hair-cell mechanotransducer channel. J Neurosci 2001;21:7013–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcotti W, van Netten SM, Kros CJ. The aminoglycoside antibiotic dihydrostreptomycin rapidly enters mouse outer hair cells through the mechano-electrical transducer channels. J Physiol 2005;567:505–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization Guidelines for the Programmatic Management of Drug-resistant Tuberculosis. Emergency update 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bitner-Glindzicz M, Osei-Lah V, Colvin I, et al. Aminoglycoside-induced deafness during treatment of acute leukaemia. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:153–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bitner-Glindzicz M, Rahman S. Ototoxicity caused by aminoglycosides. BMJ 2007;335:784–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLeod HL, Isaacs KL. Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing: insufficient data equal unsatisfactory guidance. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:842–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.