Abstract

Presently hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) particularly diabetic nephropathy are increasing in number, and cardiovascular and renal complications are the most common cause of death in these patients. The control of blood pressure (BP) is an important issue in cardiovascular and renal protection in hypertensive patients with CKD. Although hypertension is usually diagnosed based on measurements of BP recorded during a visit to a physician, that is, office BP, several studies have shown that target organ damage and prognosis are more closely associated with ambulatory BP than with office BP. It should be important to achieve the target absolute BP levels in hypertensive patients obtained either by office or home measurements or by ambulatory recordings for the cardiovascular and renal protection. Noninvasive techniques for measuring ambulatory BP have allowed BP to be monitored during both day and night. Additionally, ambulatory BP monitoring can provide information on circadian BP variation and short-term BP variability, which is suggested to be associated with cardiovascular and renal morbidity and mortality. This review will briefly summarize the emerging concept of anti-hypertensive therapy based on ambulatory BP profile in hypertensive patients with CKD.

Keywords: Blood pressure variability, diabetic nephropathy, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, renin-angiotensin system

Introduction

Presently hypertensive patients with CKD and diabetes are increasing in number, and cardiovascular complications are the most common cause of death in these hypertensive patients. Thus, it would be of considerable value to identify the mechanisms involved in the cardiovascular events associated with hypertension complicated by CKD and diabetes. Ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring has allowed an easier and more accurate determination of the circadian rhythm of BP under different pathophysiological conditions. The circadian pattern of BP in hypertensive patients with CKD and diabetes has been found to exhibit a blunted nocturnal decrease in BP, which is associated with autonomic neuropathy and nephropathy in these hypertensive patients [1]. The loss of nocturnal BP dipping has been considered to be a risk factor for the progression of nephropathy and to be of prognostic value with respect to target organ damage and cardiovascular morbidity in these CKD patients [2-4].

Estimation of ambulatory short-term BP variability

Ambulatory BP monitoring allows the acquisition of valuable information on not only the average 24-h BP, but also the variations in the BP values that happen during the course of daily life. Among the information obtained by ambulatory BP monitoring, previous studies have shown that BP variability is a complex phenomenon that involves both short- and long-lasting changes [5]. Thus the 24-h BP varies not only because of a reduction in BP during nighttime sleep and increase in the morning, but also because of sudden, quick, and short-lasting changes that occur both during the daytime and, to a lesser extent, at nighttime. This phenomenon, short-term BP variability, has been shown to depend on sympathetic vascular modulation and on atherosclerotic vascular changes [6,7]. Several previous animal studies showed that exaggerated short-term BP variability without significant changes in mean BP induced chronic cardiovascular inflammation and remodeling [8,9]. Short-term BP variability is also suggested to be clinically relevant by the fact that hypertensive patients with similar 24-h mean BP values exhibit more severe organ damage when the short-term BP variability is greater [7,10-16].

Home-measured BP variability and CKD

On the other hand, several clinical studies have provided epidemiological basis for supporting the greater accuracy of home BP monitoring compared with clinic pressures for prognosis of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular disease in long-term follow-up surveys and in cross-sectional studies. There is a general consensus that home BP monitoring is more convenient, available, and less costly than ambulatory BP monitoring, but the superiority of ambulatory BP monitoring for special clinical problems (i.e., 1) detection of non-dippers or need for sleep pressures in chronic renal disease, autonomic neuropathies, and sleep apnea; 2) estimation of short-term BP variability) is also clearly recognized [17]. Surveys of both physicians and patients suggest that home BP monitoring is both appreciated and recognized as a valuable strategy. Several experts in the field of hypertension research and care have published appeals to expand the use of home BP monitoring for routine care and to have it supported by health care systems.

Concerning home-measured BP variability, a previous study showed that high day-by-day BP variability is associated with increases in total, cardiovascular, and stroke mortality, independently of BP value and other cardiovascular risk factors in the general population of Ohasama study [18]. In the state of type 2 diabetes, while high short-term BP variability on ambulatory BP monitoring is reported to be associated with atherosclerosis and proteinuria in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes [11,19,20], the recent study by Ushigome et al. adds further information on the clinical relevance of home-measured BP variability in the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy [21]. Although the hypothesis that home-measured BP variability favors the development of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes is appealing, the cross-sectional nature of this study makes it impossible to evaluate the causal relationships between day-by-day BP variability and diabetic nephropathy. Further studies, such as outcome studies focusing on whether a therapeutic intervention reducing day-by-day BP variability also carries additional prognostic benefit by a concomitant suppression of the development of diabetic nephropathy, are warranted to confirm the prognostic value of home-measured BP variability.

Effects of Ang II type 1 receptor-specific blockers (ARB) on ambulatory short-term BP variability in diabetic nephropathy patients

Presently, inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system (RAS), such as ARB and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) are recommended as the first-line anti-hypertensive medication to treat hypertensive patients with CKD, particularly those with albuminuria. Inhibitors of RAS exerts the BP lowering effects through the suppression of circulating and tissue RAS and the additional anti-proteinuric effect through the inhibition of intra-glomerular hypertension. With respect to effects of RAS inhibitors on ambulatory BP profile in hypertensive patients with CKD, we performed a series of clinical studies by administrating ARB to hypertensive CKD patients including those on dialysis therapy.

We examined whether ARB would improve ambulatory short-term BP variability in hypertensive patients with diabetic nephropathy. A total of 30 patients with type 2 diabetes along with hypertension and overt nephropathy were enrolled in this randomized, two-period, crossover trial of 12 weeks of treatment with losartan and telmisartan [11]. After 12 weeks of treatment, 24-h, daytime, and nighttime short-term BP variability, assessed on the basis of the coefficient of variation of ambulatory BP, was significantly decreased by telmisartan. Both of losartan and telmisartan reduced urinary protein excretion and baPWV. However, compared with losartan, telmisartan significantly decreased urinary protein excretion, baPWV, and low frequency (LF)-to-high frequency (HF) ratio, an index of sympathovagal balance. Multiple regression analysis showed significant correlations between urinary protein excretion and baPWV, 24-h LF-to-HF ratio, nighttime systolic BP, and 24-h short-term systolic BP variability. Although the results of AMADEO study showed that telmisartan was more effective than losartan in reducing proteinuria in hypertensive patients with diabetic nephropathy at levels of office BP that were not different between the telmisartan and losartan treatment groups, the possible mechanisms involved in this difference in antiproteinuric effect were not elucidated [22]. The results of this study suggest that ARB, particularly telmisartan, is effective in reducing proteinuria in hypertensive patients with overt diabetic nephropathy, partly through inhibitory effects on ambulatory short-term BP variability and sympathetic nerve activity, in addition to its longer duration of action on nighttime BP reduction.

Accumulating evidence has shown that CKD patients with diabetes are increasing in number, and renal and cardiovascular complications are the most common cause of death in these patients. Thus, it is important to identify the mechanisms involved in the progression of renal impairment and cardiovascular injury associated with diabetic nephropathy. Recent evidence also indicated that multifactorial intervention is able to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and death among patients with diabetes and microalbuninuria [23]. Thus, in another study we examined the effects of intensified multifactorial intervention, with tight glucose regulation and the use of valsartan and fluvastatin, on ambulatory BP profile, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR), in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and overt nephropathy [20]. In this study we showed that the intensified multifactorial intervention including the use of valsartan and fluvastatin is able to improve ambulatory BP profile, preserve renal function, and reduce urinary albumin excretion in type 2 diabetic hypertensive patients with overt nephropathy.

Effects of ARB on ambulatory short-term BP variability in hemodialysis patients

Although cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in CKD patients on dialysis therapy, ARB is reported be effective in reducing cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis [24,25]. Thus, we examined whether ARB would improve ambulatory short-term BP variability in hypertensive patients on hemodialysis [12]. In this study hypertensive patients on hemodialysis therapy were randomly assigned to the losartan treatment group or the control treatment group. After 6- and 12-months of treatment, nighttime short-term BP variability, assessed on the basis of the coefficient of variation of ambulatory BP, was significantly decreased in the losartan group, but remained unchanged in the control group. Compared with the control group, losartan significantly decreased left ventricular mass index (LVMI), baPWV, and the plasma levels of brain natriuretic peptide and advanced glycation end products (AGE). Furthermore, multiple regression analysis showed significant correlations between changes in LVMI and changes in nighttime short-term BP variability, as well as between changes in LVMI and changes in the plasma levels of AGE. These results suggest that ARB is beneficial for the suppression of pathological cardiovascular remodeling though its inhibitory effect on ambulatory short-term BP variability during nighttime. A recent study also shows that a direct renin inhibitor aliskiren was effective for BP control and may have cardiovascular protective effects in hypertensive CKD patients on hemodialysis [26].

Effects of ARB on ambulatory short-term BP variability in peritoneal dialysis patients

Among CKD patients on peritoneal dialysis, we examined whether addition of ARB, including high-dose ARB, to conventional anti-hypertensive treatment could improve BP variability in hypertensive patients [15]. Hypertensive patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis therapy were randomly assigned to the ARB treatment groups either by candesartan or valsartan, or the control group. After the 6-months treatment, 24-h ambulatory BP values were similarly decreased in both the control group and ARB groups. However, short-term BP variability assessed on the basis of the standard deviation of 24-h ambulatory BP was significantly decreased in the ARB groups, but remained unchanged in the control group. Furthermore, parameters of cardiovascular remodeling assessed by natriuretic peptides, echocardiography, and baPWV were significantly improved in the ARB groups but not in the control group. These results indicate that ARB treatment is beneficial for the suppression of pathological cardiovascular remodeling with a decrease in BP variability in hypertensive patients on peritoneal dialysis

RAS inhibitor-based combination therapy in CKD

Although clinical guidelines specify that inhibitors of RAS are the drugs of choice for the treatment of hypertension in patients with CKD, the results of previous meta-analysis indicate that the benefits of RAS inhibitors on renal outcomes in clinical trials mainly result from a BP-lowering effect [27]. Thus, present guidelines also recommend RAS inhibitors-based combination therapy to achieve the target office BP level. The results of GUARD study showed that combination therapy with a RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic resulted in a greater reduction in albuminuria compared to that with a RAS inhibitor and calcium channel blocker (CCB) [28]. Previous studies showed that in CKD patients who have a sodium-sensitive type of hypertension, BP failed to fall during the night, thereby exhibiting non-dipper or riser types of ambulatory BP profile which correspond to abnormality of circadian BP rhythm. Although the sodium sensitivity of BP with non-dipper or riser types of ambulatory BP profile contributes as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity, both sodium restriction and thiazide diuretics are able to shift circadian BP rhythm from riser or non-dipper to dipper. Thus, RAS inhibitors-based combination therapy with thiazide diuretics may have an additional therapeutic advantage to relieve the renal and cardiovascular risks by different ways: systemic BP reduction and normalization of circadian BP rhythm.

On the other hand, the results of ACCOMPLISH study showed that combination therapy with a RAS inhibitor and CCB slows progression of nephropathy and inhibits cardiovascular death to a greater extent with a better preservation of eGFR, compared to combination therapy with a RAS inhibitor and thiazide diuretic in high-risk hypertensive patients with CKD [29]. Although the detailed mechanistic basis for this difference in cardiorenal protection, in spite of similar mean 24-hour systolic and diastolic BP patterns by combination therapy [30], should be resolved by future studies, combination therapy with a RAS inhibitor and CCB is reported to effectively decrease central aortic pressure and ambulatory short-term BP variability with a preventive effect on the progression of arterial stiffness [31,32].

The direct renin inhibitor aliskiren is available as alternative or complementary approaches to pharmacological RAS blockade. Direct renin inhibitors constitute a novel class of RAS antagonists that block the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I. Aliskiren, the first approved compound of this class, reduces BP levels with similar potency as ACE inhibitor and ARB. Aliskiren as add-on treatment to standard therapy including the optimal dose of losartan, in the AVOID study, reduced albuminuria and slowed development of renal dysfunction more than placebo across different levels of eGFR in patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and nephropathy [33-35]. The long-term nephroprotective potential of aliskiren-based therapy and its superiority over existing therapies as a possible first-line regimen remains to be elucidated.

Chronotherapy as a possible another therapeutic option in CKD

Finally, given that nocturnal BP non-dipping is a potential independent risk factor for CKD progression and development of cardiorenal syndrome, the timing of administration of anti-hypertensive drugs may be of relevance. Even compounds with recommended once-daily administration based on their pharmacokinetic properties may reduce nocturnal BP level more efficiently when applied in the evening, thereby achieving partial restoration of the physiological nocturnal BP dipping pattern and exerting efficient cardiovascular and renal protection [36]. Although antihypertensive “chronotherapy” has not been formally demonstrated to affect CKD progression, that the anti-proteinuric efficacy of the ARB valsartan or candesartan was associated with an increased day:night BP-level ratio on ambulatory or home BP monitoring induced by evening dosing is noteworthy [37,38].

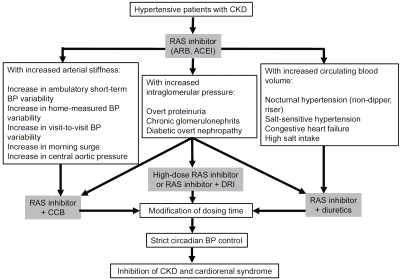

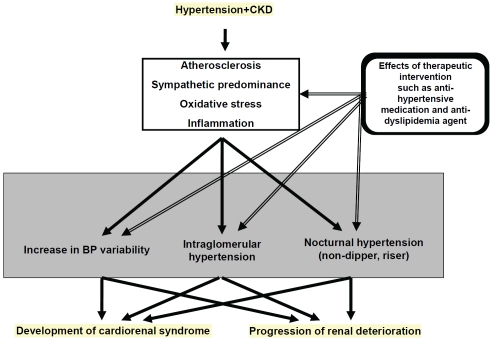

The proposed strategy of anti-hypertensive therapy in hypertensive patients with CKD is summarized as schema (Figure 1). In conclusion, employing anti-hypertensive therapy based on ambulatory BP profile in the management of hypertensive patients with CKD may be effective to slow the progression of renal impairment and suppress the development of cardiovascular disease in these patients. Further clinical studies to confirm of the prognostic value of ambulatory BP profile, particularly ambulatory short-term BP variability, would need to be provided by outcome studies focusing on whether a therapeutic intervention improving ambulatory BP profile such as reducing BP variability also carries additional prognostic benefit, by con-comitantly reducing also the rate of renal deterioration and cardiovascular events (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Schema showing the proposed strategy of RAS inhibitor-based combination therapy for hypertensive patients with CKD. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, Ang II type 1 receptor-specific blocker; BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DRI, direct renin inhibitor; RAS, renin-angiotensin system.

Figure 2.

Increasing importance of clinical studies examining effects of various therapeutic intervention such as anti-hypertensive medication and anti-dyslipidemia agent on altered ambulatory BP profile in hypertensive patients with CKD. BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported in part by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, by Health and Labor Sciences Research grant; and by grants from Salt Science Research Foundation (No. 1033, 1134), the Kidney Foundation, Japan (JKFB11-25) and Strategic Research Project of Yokohama City University. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Spallone V, Bernardi L, Ricordi L, Solda P, Maiello MR, Calciati A, Gambardella S, Fratino P, Menzinger G. Relationship between the circadian rhythms of blood pressure and sympathovagal balance in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes. 1993;42:1745–1752. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.12.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakano S, Fukuda M, Hotta F, Ito T, Ishii T, Kitazawa M, Nishizawa M, Kigoshi T, Uchida K. Reversed circadian blood pressure rhythm is associated with occurrences of both fatal and nonfatal vascular events in NIDDM subjects. Diabetes. 1998;47:1501–1506. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturrock ND, George E, Pound N, Stevenson J, Peck GM, Sowter H. Non-dipping circadian blood pressure and renal impairment are associated with increased mortality in diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2000;17:360–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmas W, Pickering TG, Teresi J, Schwartz JE, Moran A, Weinstock RS, Shea S. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and all-cause mortality in elderly people with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2009;53:120–127. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancia G, Parati G. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and organ damage. Hypertension. 2000;36:894–900. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parati G, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. Neural cardiovascular regulation and 24-hour blood pressure and heart rate variability. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;783:47–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb26706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamura K, Tsurumi Y, Sakai M, Tanaka Y, Okano Y, Yamauchi J, Ishigami T, Kihara M, Hirawa N, Toya Y, Yabana M, Tokita Y, Ohnishi T, Umemura S. A possible relationship of nocturnal blood pressure variability with coronary artery disease in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2007;29:31–42. doi: 10.1080/10641960601096760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eto M, Toba K, Akishita M, Kozaki K, Watanabe T, Kim S, Hashimoto M, Ako J, Iijima K, Sudoh N, Yoshizumi M, Ouchi Y. Impact of blood pressure variability on cardiovascular events in elderly patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:1–7. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kudo H, Kai H, Kajimoto H, Koga M, Takayama N, Mori T, Ikeda A, Yasuoka S, Anegawa T, Mifune H, Kato S, Hirooka Y, Imaizumi T. Exaggerated blood pressure variability superimposed on hypertension aggravates cardiac remodeling in rats via angiotensin II system-mediated chronic inflammation. Hypertension. 2009;54:832–838. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eguchi K, Ishikawa J, Hoshide S, Pickering TG, Schwartz JE, Shimada K, Kario K. Night time blood pressure variability is a strong predictor for cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:46–51. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masuda S, Tamura K, Wakui H, Kanaoka T, Ohsawa M, Maeda A, Dejima T, Yanagi M, Azuma K, Umemura S. Effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker on ambulatory blood pressure variability in hypertensive patients with overt diabetic nephropathy. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:950–955. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsuhashi H, Tamura K, Yamauchi J, Ozawa M, Yanagi M, Dejima T, Wakui H, Masuda S, Azuma K, Kanaoka T, Ohsawa M, Maeda A, Tsurumi-Ikeya Y, Okano Y, Ishigami T, Toya Y, Tokita Y, Ohnishi T, Umemura S. Effect of losar tan on ambulatory short-term blood pressure variability and cardiovascular remodeling in hypertensive patients on hemodialysis. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozawa M, Tamura K, Okano Y, Matsushita K, Ikeya Y, Masuda S, Wakui H, Dejima T, Shigenaga A, Azuma K, Ishigami T, Toya Y, Ishikawa T, Umemura S. Blood pressure variability as well as blood pressure level is important for left ventricular hypertrophy and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in hypertensives. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009;31:669–679. doi: 10.3109/10641960903407033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothwell PM. Limitations of the usual bloodpressure hypothesis and importance of variability, instability, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:938–948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shigenaga A, Tamura K, Dejima T, Ozawa M, Wakui H, Masuda S, Azuma K, Tsurumi-Ikeya Y, Mitsuhashi H, Okano Y, Kokuho T, Sugano T, Ishigami T, Toya Y, Uchino K, Tokita Y, Umemura S. Effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker on blood pressure variability and cardiovascular remodeling in hypertensive patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;112:c31–40. doi: 10.1159/000210572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shintani Y, Kikuya M, Hara A, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, Asayama K, Inoue R, Obara T, Aono Y, Hashimoto T, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Hoshi H, Satoh H, Imai Y. Ambulatory blood pressure, blood pressure variability and the prevalence of carotid artery alteration: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1704–1710. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328172dc2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilo G, Parati G. Rate of blood pressure changes assessed by 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: another meaningful index of blood pressure variability? J Hypertens. 2011;29:1054–1058. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328347bb24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, Asayama K, Hara A, Obara T, Inoue R, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Imai Y. Day-by-day variability of blood pressure and heart rate at home as a novel predictor of prognosis: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2008;52:1045–1050. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.104620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozawa M, Tamura K, Okano Y, Matsushita K, Yanagi M, Tsurumi-Ikeya Y, Oshikawa J, Hashimoto T, Masuda S, Wakui H, Shigenaga A, Azuma K, Ishigami T, Toya Y, Ishikawa T, Umemura S. Identification of an increased shortterm blood pressure variability on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring as a coronary risk factor in diabetic hypertensives. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009;31:259–270. doi: 10.1080/10641960902822518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanaoka T, Tamura K, Moriya T, Tanaka K, Konno Y, Kondoh S, Toyoda M, Umezono T, Fujikawa T, Ohsawa M, Dejima T, Maeda A, Wakui H, Haku S, Yanagi M, Mitsuhashi H, Ozawa M, Okano Y, Ogawa N, Yamakawa T, Mizushima S, Suzuki D, Umemura S. Effects of Multiple Factorial Intervention on Ambulatory BP Profile and Renal Function in Hypertensive Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Overt Nephropathy - A Pilot Study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2011;33:255–263. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2011.583971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ushigome E, Fukui M, Hamaguchi M, Senmaru T, Sakabe K, Tanaka M, Yamazaki M, Hasegawa G, Nakamura N. The coefficient variation of home blood pressure is a novel factor associated with macroalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertens Res. 2011 doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.128. (e-pub ahead of print 4 August 2011; doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.128) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakris G, Burgess E, Weir M, Davidai G, Koval S. Telmisartan is more effective than losartan in reducing proteinuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2008;74:364–369. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:580–591. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki H, Kanno Y, Sugahara S, Ikeda N, Shoda J, Takenaka T, Inoue T, Araki R. Effect of angiotensin receptor blockers on cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:501–506. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cice G, Di Benedetto A, D'Isa S, D'Andrea A, Marcelli D, Gatti E, Calabro R. Effects of telmisartan added to Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in hemodialysis patients with chronic heart failure a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1701–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morishita Y, Hanawa S, Chinda J, Iimura O, Tsunematsu S, Kusano E. Effects of aliskiren on blood pressure and the predictive biomarkers for cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:308–313. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casas JP, Chua W, Loukogeorgakis S, Vallance P, Smeeth L, Hingorani AD, MacAllister RJ. Effect of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes: systematic review and metaanalysis. Lancet. 2005;366:2026–2033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakris GL, Toto RD, McCullough PA, Rocha R, Purkayastha D, Davis P. Effects of different ACE inhibitor combinations on albuminuria: results of the GUARD study. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1303–1309. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakris GL, Sarafidis PA, Weir MR, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Jamerson K, Velazquez EJ, Staikos-Byrne L, Kelly RY, Shi V, Chiang YT, Weber MA. Renal outcomes with different fixed-dose combination therapies in patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events (ACCOMPLISH): a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamerson KA, Devereux R, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Velazquez EJ, Weir M, Kelly RY, Hua TA, Hester A, Weber MA. Efficacy and duration of benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide on 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure control. Hypertension. 2011;57:174–179. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.159939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichihara A, Kaneshiro Y, Sakoda M, Takemitsu T, Itoh H. Add-on amlodipine improves arterial function and structure in hypertensive patients treated with an angiotensin receptor blocker. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;49:161–166. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31803104e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsui Y, Eguchi K, O'Rourke MF, Ishikawa J, Miyashita H, Shimada K, Kario K. Differential effects between a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic when used in combination with angiotensin II receptor blocker on central aortic pressure in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;54:716–723. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parving HH, Persson F, Lewis JB, Lewis EJ, Hollenberg NK. Aliskiren combined with losartan in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2433–2446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persson F, Lewis JB, Lewis EJ, Rossing P, Hollenberg NK, Parving HH. Impact of baseline renal function on the efficacy and safety of aliskiren added to losartan in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2304–2309. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persson F, Lewis JB, Lewis EJ, Rossing P, Hollenberg NK, Parving HH. Aliskiren in combination with losartan reduces albuminuria independent of baseline blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1025–1031. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07590810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Fernandez JR, Portaluppi F, Fabbian F, Smolensky MH. Circadian rhythms in blood pressure regulation and optimization of hypertension treatment with ACE inhibitor and ARB medications. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:383–391. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermida RC, Calvo C, Ayala DE, Lopez JE. Decrease in urinary albumin excretion associated with the normalization of nocturnal blood pressure in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2005;46:960–968. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000174616.36290.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kario K, Hoshide S, Shimizu M, Yano Y, Eguchi K, Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, Shimada K. Effect of dosing time of angiotensin II receptor blockade titrated by self-measured blood pressure recordings on cardiorenal protection in hypertensives: the Japan Morning Surge-Target Organ Protection (J-TOP) study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1574–1583. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283395267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]