Abstract

Purpose

To determine the metabolism and tissue distribution of the dietary chemoprotective agent sulforaphane following oral administration to wild-type and Nrf2 knockout (Nrf2−/−) mice.

Methods

Male and female wild-type and Nrf2−/− mice were given sulforaphane (5 or 20 µmoles) by oral gavage, and plasma, liver, kidney, small intestine, colon, lung, brain and prostate were collected at 2, 6 and 24 hours (h). The five major metabolites of sulforaphane were measured in tissues by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry.

Results

Sulforaphane metabolites were detected in all tissues at 2 and 6 h post gavage, with concentrations being the highest in the small intestine, prostate, kidney and lung. A dose- dependent increase in sulforaphane concentrations was observed in all tissues except prostate. At 5 µmole, the Nrf2−/− genotype had no effect on sulforaphane metabolism. Only Nrf2−/− females given 20µmoles sulforaphane for 6 h exhibited a marked increase in tissue sulforaphane metabolite concentrations. However, the relative abundance of each metabolite was not strikingly different between genders and genotypes.

Conclusions

Sulforaphane is metabolized and reaches target tissues in both wild-type and Nrf2−/− mice. Together these data provide further evidence that sulforaphane is bioavailable and may be an effective dietary chemoprevention agent for several tissue sites.

Keywords: broccoli, metabolism, Nrf2, sulforaphane, tissue distribution

Introduction

Epidemiological studies have shown an inverse association between cruciferous vegetable intake and cancer risk in many tissues including lung, bladder, colon and prostate (1–4). Cruciferous vegetables contain high concentrations of glucosinolates, which are hydrolyzed to isothiocyanates (ITCs) by myrosinase, an enzyme endogenous in the plant and present in colonic microflora (5). The ITCs have been extensively studied for their anti-cancer properties and have shown promise in preclinical and clinical settings (6–8). Sulforaphane (SFN) is a well studied ITC derived from the glucosinolate glucoraphanin, which is abundant in broccoli and broccoli sprouts. The first identified and most studied mechanism for SFN-mediated chemoprevention is through the induction of phase II enzymes via Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NF-E2) related factor 2) signaling. Nrf2 is well established as an important mediator of electrophile and reactive oxygen species toxicity (9). Upon electrophile- or reactive oxygen species-induced cellular stress, Nrf2 is released from cytoplasmic Keap1 and translocates to the nucleus where it binds antioxidant response element (ARE) sites on many phase I and II metabolism genes, and phase III transport genes. The upregulation of antioxidant and xenobiotic metabolism is believed to protect cells from carcinogen and/or oxidative stress exposure by expediting their inactivation and removal via metabolism and excretion. Studies utilizing the Nrf2−/− mouse have highlighted the importance of Nrf2-mediated phase I, II and III enzyme induction in chemoprevention and its role in SFN mediated cytoprotection (9). Importantly, SFN is metabolized through Nrf2-mediated phase II and III proteins, such as glutathione-S-transferase (GST) and multidrug resistance associated protein-1 (10). Therefore, Nrf2 is believed be to an important player in SFN metabolism and export from the cell. However, it is currently not known what impact, if any, loss of Nrf2 has on SFN metabolism and tissue distribution in vivo. For example, one hypothesis is that Nrf2 target genes (such as GSTs) become induced by SFN and then convert the parent compound to metabolites with important chemopreventive activity, which might be lost in the Nrf2 null background.

To date, there is little precise information on the distribution of SFN and its metabolites in various tissues of the body following dietary administration. Pharmacokinetic (PK) studies in rodents have focused on either free SFN or its metabolite SFN-glutathione (SFN-GSH), and they have not attempted to measure other major SFN metabolites (11, 12). Only one human study included PK analysis of all five major SFN metabolites (13). In addition, a limited number of studies have examined tissues, such as small intestine and lung for SFN content (14, 15). One human study reported dithiocarbamate (a measure of total ITC content) concentrations in mammary tissue after consumption of a broccoli preparation (16). A comprehensive profiling of SFN bioavailability and tissue distribution in vivo is critical for understanding the potential efficacy of SFN as a dietary chemoprevention agent for various cancers.

Thus, we performed high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of all five SFN metabolites in order to determine SFN metabolism and tissue distribution in both Nrf2−/− and wild-type mice. SFN has been used in the Nrf2−/− mouse model (17, 18) and the present study provides insight into how Nrf2−/− impacts SFN metabolism. In addition, this is the first study to show tissue specific concentrations and metabolite profiles after oral SFN administration.

Materials and Methods

Materials

R,S-SFN, SFN-GSH, SFN-Cysteine (SFN-Cys) and SFN-N-acetylcysteine (SFN-NAC) were purchased from LKT laboratories (St Paul, MN). Deuterated N-acetylcysteine was synthesized according to Slatter et al. (19). For synthesis of the internal standard (deuterated SFN-NAC), 0.1 mM SFN, 10 mM deuterated NAC, and 0.04 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.8 were mixed together and stirred for 4 h at room temperature. The mixture was then acidified with 1 N HCl and applied to an equilibrated StrataX 33 µm reverse phase cartridge (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), washed, and then eluted in 50:50 acetonitrile and water. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Darmstadt, Germany).

Treatment of animals

Wild-type (ICR) mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories Inc. (Indianapolis, IN) and Nrf2 knockout mice (ICR background) were bred from a mouse colony originally obtained from RIKEN BioResource Center (Ibaraki, Japan). Mice were maintained at 22°C on a 12 hr light-dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum throughout the study. One week prior to SFN treatment the mice (~8 months of age) were switched from standard laboratory chow to a purified AIN93M diet that did not contain tert-butylhyroquinone (TBHQ). Mouse weights were recorded prior to treatment (males 48.1 ± 5.7 g and females 44.3 ± 8.2 g). Mice were treated with either 5 or 20 umoles of SFN in corn oil, which is equivalent to 110 µmoles SFN/kg body weight or 440 µmoles SFN/kg body weight of SFN, respectively, or corn oil only (sham control) by gavage and sacrificed at 2, 6, and 24 h after gavage. At each time point the mice were euthanized with CO2 and the following tissues were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen: brain, liver, kidney, small intestine (SI) mucosa, colonic mucosa, lung, prostate, and plasma. For SI and colon, the intestine was removed, washed with PBS, and mucosal scrapings were collected. For plasma, whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture, transferred to a tube containing EDTA and centrifuged at high speed for 1 min to collect the plasma. The plasma was immediately acidified with 10% v/v ice cold TFA. Animal handling and procedures were performed in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon State University.

LC-MS/MS analysis

The methods for LC-MS/MS analysis were performed as described in Al Janobi et al. (20), with minor modifications. For most solid tissues ~50 mg of frozen tissue was homogenized using mortar and pestle and liquid nitrogen. After homogenization 50 µL of 10% TFA (v/v) in water was added to the sample along with 5 µL of 100 µM internal standard (deuterated SFN-NAC) and vortexed vigorously. The homogenate was frozen at −80°C then thawed, vortexed vigorously, centrifuged at 11,600 × g at 4 °C for 5 min and the supernatant was subsequently filtered through a 0.2 µm pore size filter. For tissues such as brain and kidney, half of the brain and one entire kidney from each mouse was homogenized and used for metabolite analysis. For plasma the samples were acidified, centrifuged and filtered as described above.

Ten µL of filtered sample were separated on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using a reversed-phase Phenomenex Kinetex PFP 2.6 µm 100Å 100 × 2.6 mm HPLC column. The flow rate was 0.25 mL/min using 0.1% FA in water (solution A) and 0.1% FA in acetonitrile (solution B). The gradient was as follows: 5% B increasing to 30% over 1.5 min, held at 30% for 1.5 min, washed out with 90% B for 3.5 min and re-equilibrated to 5% B for 3.5 min. The LC eluent was analyzed by an API triple quad mass spectrometer 3200 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with electrospray ionization in positive mode. Tandem mass spectrometry using multiple reaction monitoring was used to detect the analytes with the following precursor and product ions: SFN (178>114), SFN-GSH (485>114), SFN-Cysteinlyglycine (SFN-CG) (356>114), SFN-Cys (299>114), SFN-NAC (341>114). Spike and recovery experiments using the internal standard confirmed that >80% of all compounds were recovered following the processing protocols outlined. Quantification was performed by using a standard curve ranging from 0.156 to 25 µM. Acquisition and quantification was performed using Analyst software (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA).

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between groups were compared by 2-way ANOVA analysis as indicated in each figure.

Results

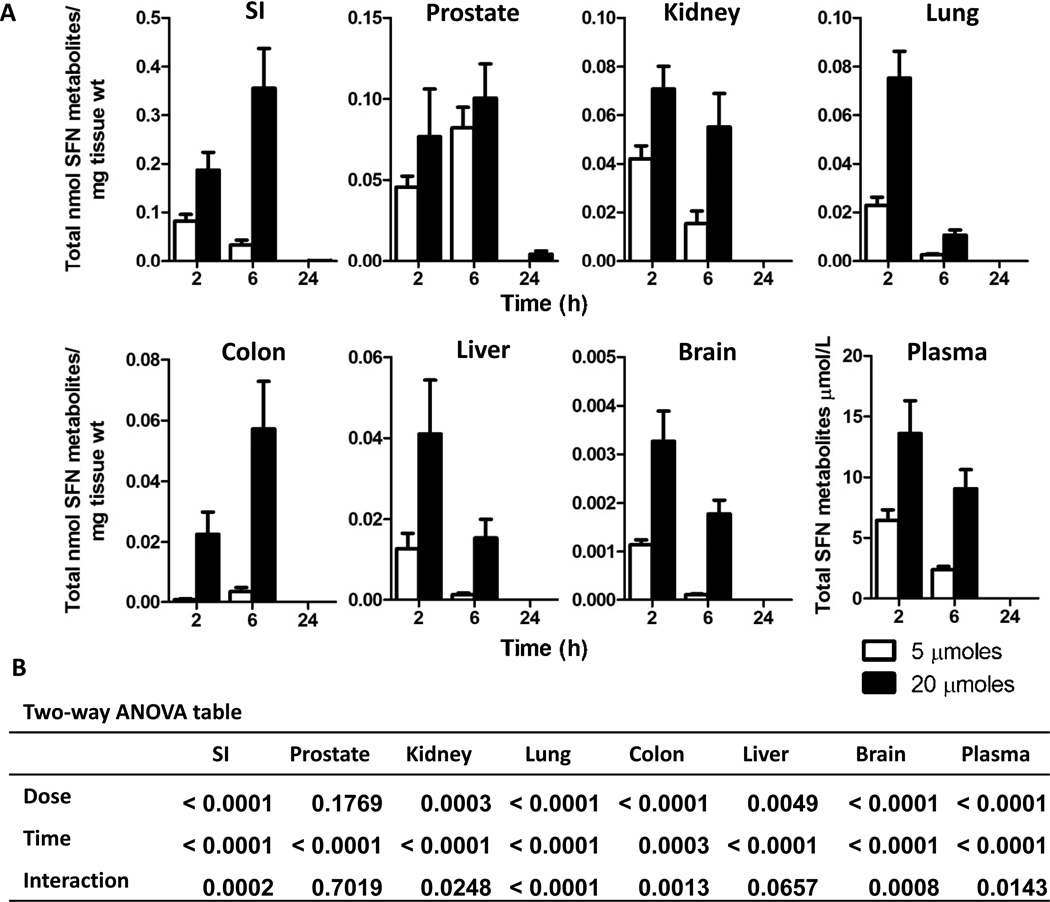

In wild-type mice, individual SFN metabolites were quantified in tissues at 2, 6 and 24 h post gavage with SFN or sham control. Nrf2 wild-type mice had SFN metabolites present in all tissues tested after SFN treatment whereas no SFN metabolites were detected in any tissues from sham treated mice. Using the sum of all SFN compounds detected, including free SFN, SFN-GSH, SFN-Cys and SFN-NAC, SFN treated mice exhibited a dose dependent increase in tissue concentrations (Figure 1A and B), with concentrations being the highest in the SI, prostate, kidney and lung. In plasma, SFN metabolite concentrations were highest at 2 h but were not detectable by 24 h. Most tissues followed similar kinetics as plasma, with highest concentrations at 2 h and completely cleared by 24 h. Colon, SI, and prostate had higher concentrations at 6 h, and only in the SI and prostate were low levels of metabolites still detectable at 24 h in mice given 20 µmole SFN (Figure 1). Analysis of plasma concentrations with the different tissue concentrations revealed that only brain and lung correlated statistically with plasma concentrations (Table 1), despite the fact that most tissues followed similar kinetics as observed in plasma. No gender differences in SFN metabolism and tissue distribution were observed in the wild-type mice (data not shown).

Figure 1. Dose dependent increase and rapid clearance of total SFN metabolites in most wild-type mouse tissues.

(A) Male and female wild-type mice received gavage of either 5 (open bars) or 20 (solid bars) µmoles of SFN and tissues were collected at 2, 6, and 24 h. Data in graphs represent the mean ± SEM of the sum of all SFN metabolites normalized to tissue weight (n=12 for all tissues except prostate; prostate n=6). (B) Two-way ANOVA analysis of the data.

Table 1.

Correlation between plasma and tissue concentrations in wild-type mice.

| Correlation coefficient (p-value) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2h |

6h |

|||

| Tissue | 5 µmoles | 20 µmoles | 5 µmoles | 20 µmoles |

| SI | 0.21 (0.504) | 0.57 (0.066) | 0.42 (0.175) | −0.18 (0.572) |

| Colon | 0.05 (0.868) | −0.26 (0.445) | 0.03 (0.916) | 0.03 (0.929) |

| Liver | 0.06 (0.854) | 0.18 (0.606) | 0.22 (0.487) | 0.38 (0.217) |

| Kidney | −0.01 (0.965) | 0.30 (0.377) | 0.07 (0.818) | 0.37 (0.236) |

| Lung | 0.56 (0.060) | 0.83 (0.001)* | 0.72 (0.008)* | −0.24 (0.453) |

| Brain | 0.77 (0.003)* | 0.76 (0.006)* | 0.59 (0.043)* | 0.72 (0.008)* |

| Prostate | 0.29 (0.579) | −0.27 (0.601) | 0.55 (0.254) | 0.72 (0.103) |

p-value < 0.05 by correlation analysis

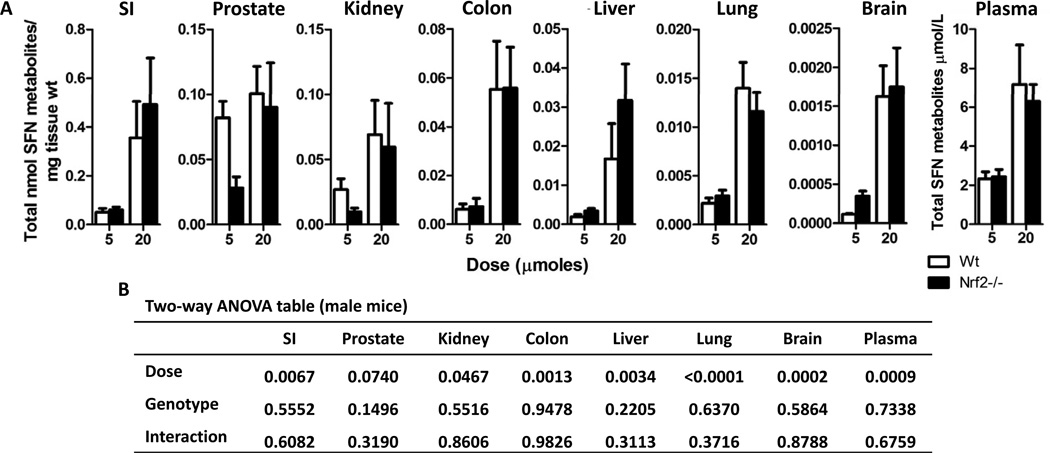

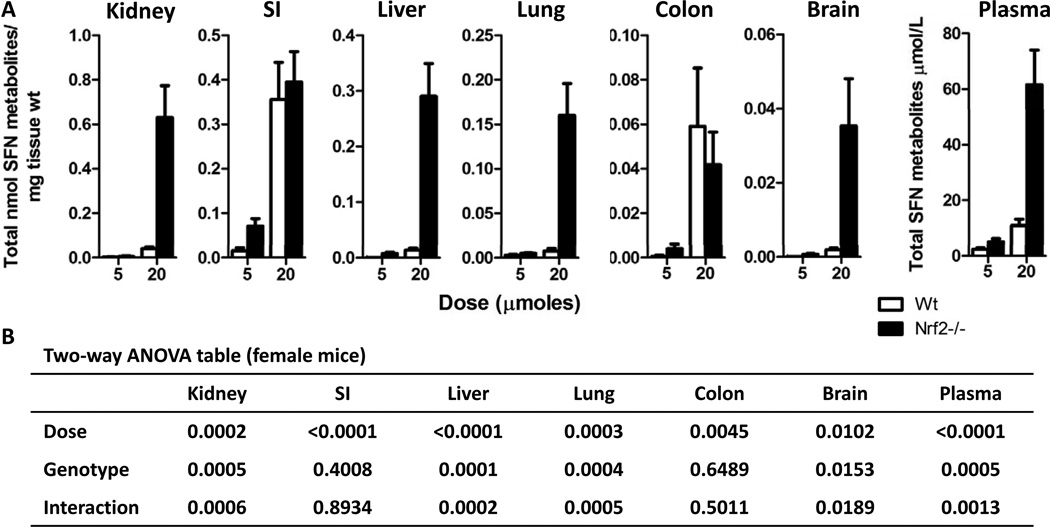

To determine if the absence of Nrf2 has an impact, we compared the metabolism of SFN between Nrf2−/− and Nrf2 wild-type mice. Initially it appeared that the Nrf2−/− genotype resulted in markedly higher SFN metabolite concentrations; however, upon closer analysis a genotype effect was only apparent in female mice at the 20 µmole dose and 6 h time point. Thus, a comparison between Nrf2−/− and wild-type male mice at 6 h (Figure 2A and B) revealed a significant dose effect but no genotype effect on SFN tissue concentrations in nearly all tissues. Although not statistically significant, the exceptions were kidney and prostate at 5 µmole SFN, which had lower levels in Nrf2 null versus wild type mice, and brain at the same SFN dose, which had higher levels in the knockout. Similar results were observed at 2 h when comparing male mice across genotypes and female mice across genotypes (data not shown). In female mice administered 5 and 20 µmole SFN, a general trend was observed in which the tissue concentrations were higher in Nrf2−/− compared with wild type mice, with certain exceptions (Figure 3A and B). Thus, Nrf2−/− females in the 20 µmole dose group and 6 h time point had drastically higher SFN metabolite concentrations compared to wild-type animals in all tissues, except the SI and Colon (Figure 3A and B). A similar trend was observed at the 5 µmole SFN dose in most tissues, with higher metabolite concentrations in null versus wild type, although this was not always statistically significant. Data in the SI and colon provide indirect evidence that the differences noted in other tissues were unlikely to be due to an error in SFN dosing between the two genotypes.

Figure 2. Nrf2 status has no effect on SFN metabolite concentrations in male mice.

(A) Data shown in graph are male wild-type (open bars) and male Nrf2−/− (solid bars) mice treated with either 5 or 20 µmoles of SFN for 6 h. Data in graphs represent the mean ± SEM of the sum of all SFN metabolites normalized to tissue weight (n=6). (B) Two-way ANOVA analysis of the data.

Figure 3. Female Nrf2−/− mice had dramatically higher SFN metabolite concentrations compared to female wild-type mice.

(A) Data shown in graph are female wild-type (open bars) and female Nrf2−/− (solid bars) mice treated with either 5 or 20 µmoles of SFN for 6 h. Data in graphs represent the mean ± SEM of the sum of all SFN metabolites normalized to tissue weight (n=6). (B) Two-way ANOVA analysis of the data.

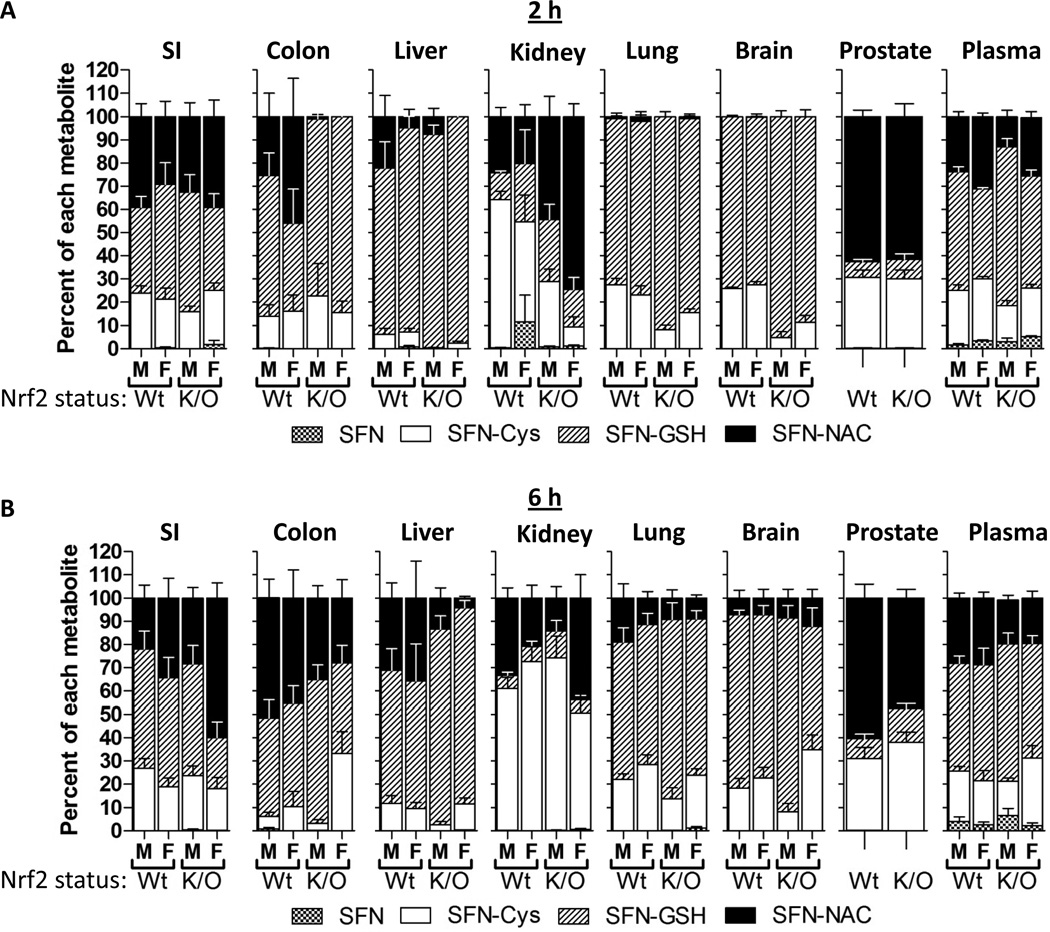

Individual SFN metabolites were quantified, and the relative abundance of each was determined for each tissue. The relative abundance of each metabolite varied among the tissues, across gender and genotype, as well as across time and dose (Figure 4A and B). Surprisingly, there were no drastic differences across genotype, although at the 2 h time point there was a trend towards more SFN-GSH in the colon, liver, lung, brain and plasma from Nrf2−/− mice compared to wild-type mice. For some tissues, such as lung and brain, the amount of SFN-NAC increased from the 2 h to 6 h time points. Other tissues such as SI, prostate, and plasma did not vary much across genotype, gender, and time. SFN-GSH was the most abundant metabolite in liver, lung and brain, whereas SFN-NAC was the most abundant metabolite in prostate. Interestingly, metabolite ratios in the kidney at 2 h were somewhat variable across gender and genotype, but by 6 h SFN-Cys was the most abundant metabolite in both genders and genotypes. SI, colon, and plasma had a relatively even distribution of SFN-NAC, SFN-GSH and SFN-Cys. Only low concentrations of free SFN were detected, and in a few tissues, with plasma having the highest percentage (<10%). Small quantities of SFN-CG were detected in a few plasma samples (<1%), but not in other tissues.

Figure 4. The relative abundance of each SFN metabolite is similar across genotype and gender but variable between tissues.

Percent each SFN metabolite represents within the SFN metabolites in different tissues in male (M) or female (F) and wild-type (Wt) or Nrf2−/− (K/O) mice at 2 (A) and 6 (B) h after 20 µmole dose of SFN. Data in graphs represent mean ± SEM (n=6).

Discussion

In the present study, we conducted experiments using Nrf2−/− and Nrf2 wild-type mice to determine the metabolism and tissue distribution of SFN following oral administration. Using LC-MS/MS analysis we sought to quantify SFN and four major metabolites (SFN-GSH, SFN-CG, SFN-Cys and SFN-NAC) in plasma, SI, colon, liver, kidney, lung, brain and prostate. Most studies in rodents and humans have reported peak plasma concentrations of SFN and its metabolites occurring between 1 and 3 h after SFN administration (11–13). Following SFN gavage, SFN metabolites were detected in all tissues at 2 and 6 h, and a dose dependent increase in tissue concentrations was observed in all tissues except for the prostate. In liver, kidney, lung, brain and plasma the highest concentrations were at 2 h, but in SI, colon and prostate the highest concentrations were at 6 h. This indicated that SFN metabolites may be accumulating in certain tissues, and that peak plasma concentrations do not always align precisely with target tissues of major cancers, such as prostate and colon. Although no gender difference was observed in SFN metabolism in the wild-type mice, in Nrf2−/− mice at the higher dose and 6 h time point there was a marked increase in tissue concentrations in the female mice compared to the male mice, and a similar trend also was seen at the lower SFN dose. Interestingly, the relative abundance of each metabolite was not strikingly different between genders and genotypes, despite some variability on a case-by-case basis. This study is the first to show detailed LC-MS/MS analysis of SFN metabolites in mouse tissues, and to compare SFN metabolite profiles between Nrf2−/− and wild-type mice.

Although there have been several studies showing PK of SFN in rodents and humans, tissue distribution is still largely unknown. Herein we report that the tissue concentrations of SFN metabolites vary as much as 100 fold between different tissues. For example, SI had the highest concentration at 0.355 nmole SFN metabolites/mg of tissue whereas brain had 0.003 nmole SFN metabolites/mg of tissue (Figure 1). It has been reported that 74% of a SFN dose was absorbed in human jejunum (21), so high concentrations in the SI are likely not a result of poor bioavailability, although we did not directly test that here. Currently little is known regarding the ability of SFN metabolites to cross the blood-brain barrier, but here we report low concentration in the brain which likely indicates that SFN metabolites do not readily cross the blood-brain barrier, Tissues such as liver, kidney, lung and prostate had comparable concentrations at 2h, ranging from 0.075 nmole SFN metabolites/mg of tissue in lung to 0.041 nmole SFN metabolites/mg of tissue in liver. The abundance of individual metabolites also varied between tissues. SFN-GSH, SFN-Cys and SFN-NAC represented the highest proportion of SFN metabolites in most tissues. For some tissues, such as prostate and lung, SFN-NAC and SFN-GSH were the most abundant metabolites, respectively. The in vivo bioactivity of each metabolite is still unclear, although it has been reported that the SFN-Cys and SFN-NAC metabolites are the bioactive intermediates targeting histone deacetylases (22).

Interestingly, because ITC thiol conjugates can dissociate into free ITCs under physiological conditions (23), it has been postulated that these thiol conjugates can be considered prodrugs of the parent compound (24). Studies have shown similar efficacy from either free ITC or the N-acetylcysteine (NAC) conjugated ITC in vitro, in cancer cells, or in rodent cancer models in vivo (24–29). The metabolism of the ITC and ITC-NAC compounds in the latter studies is unknown, but from the current investigation it can be expected that tissue concentrations in the mice that received the free ITCs were predominately in the form of thiol conjugates. The metabolism of orally administered ITC-NAC conjugates is unknown and would be an interesting area of future research. These differences in total and individual SFN metabolite tissue concentrations could impact the bioactivity of SFN in different tissues, and merits further investigation. From the current data it is clear that thorough accounting of SFN in vivo requires analysis of at least four of the five main metabolites. These data also support the hypothesis that repeated consumption of cruciferous vegetables is required to maintain SFN metabolite concentrations in tissues.

In our study we observed striking differences between male and female Nrf2−/− mice at the 20 µmole dose and 6 h time point. It has been reported that female Nrf2−/− mice have significantly higher morbidity and mortality, even in the absence of apparent exogenous stress (30). Interestingly, Ma et al. reported that 88% and 47% of the death in Nrf2−/− female and male mice, respectively, were caused by renal failure and severe glomerulonephritis. In the present study, the Nrf2−/− female mice in the 20 µmole SFN/6 h group had apparent toxicity after the SFN treatment manifested as lethargy and non-responsiveness, and as much as 23-fold higher concentrations of SFN metabolites in all tissues (except for the SI and colon) compared to the corresponding wild-type females (Figure 3). The observation that the SI and colon were the only tissues that had similar concentrations as observed in the wild-type mice indicates that the differences in tissues concentrations occur post-absorption. We speculate that the female Nrf2−/− mice in our study had some degree of glomerulonephritis as a result of lacking Nrf2, and upon receipt of the higher dose (20 µmole SFN) underwent acute kidney failure and could not excrete the SFN metabolites in the urine, thus leading to an accumulation in tissues and ultimately toxicity. Furthermore, it is possible that this potential kidney damage is compounding the impact of reduced inducibility of phase III efflux transporters on clearance of SFN compounds from the tissues, thus contributing to the high tissue concentrations observed. Further study confirming degree of glomerulonephritis and/or altered phase III transporter expression is an important area for future research to understand the mechanisms accouonting for this response in the Nrf2−/− females. Also, although differences between wild-type female and male mice in basal and inducible GST activity as well as hepatotoxicity have previously been reported (31–33), we did not observe a difference in SFN metabolism between wild-type males and wild-type females. Taken together, these data illuminate the need for caution when selecting either male or female Nrf2−/− mice for xenobiotic studies.

The importance of Nrf2 in drug metabolism is well documented (34). As expected, it has been reported that Nrf2−/− mice have much lower expression and lack the inducibility of phase I, II, and III enzymes (30, 33, 35). Several groups have shown that Nrf2−/− mice are more susceptible to experimentally induced colon cancer (36–38). In the context of SFN treatment, one study reported that the protective effects of SFN administration in a Parkinson’s disease model was lost in Nrf2−/− mice (18). Similarly, another group reported that topical SFN administration in a UVB induced skin inflammation model was only able to restore sunburn cells back to basal levels in mice that were wild-type for Nrf2 (17). The working hypothesis is that the loss in SFN-mediated protection in these models is partially attributed to altered metabolism of SFN in Nrf2−/− mice. In the current report we show that SFN metabolism and tissue distribution is nearly identical between wild-type and Nrf2−/− mice (Figure 2 and 3), with the exception of female Nrf2−/− mice given 20 µmole for 6 h (see discussion above regarding these mice). Also, across genotypes there were no drastic differences in the relative abundance of each metabolite, even though the Nrf2−/− females at the high dose and 6 h time point had dramatically higher tissue concentrations. Several aspects of drug metabolism could contribute to this apparent disconnect between SFN metabolism and Nrf2 status. For example, cross talk between the many different nuclear receptors involved in drug metabolism has been reported, and several members of the GST family are regulated independently of Nrf2 (39, 40). Indeed, it has been shown that dextran sulfate sodium treatment caused induction of GSTM1 protein in colonic tissues of Nrf2−/− mice (36), indicating either a separate pathway for induction or retention of inducibility of GSTM1 in the colon of these mice. Also, it has been shown that SFN metabolites can undergo facile thiol exchange reactions (41), indicating that interconversion between SFN metabolites may occur, independent of enzymatic activity in vivo. Future research will be important to elucidate exactly what factors are contributing to this disconnect between SFN metabolism and Nrf2 driven phase II enzyme induction. From these data we conclude that Nrf2 status does not have a marked impact on SFN metabolism and tissue distribution in mice, and therefore the differences in SFN efficacy observed in other studies are likely not related to metabolism and biodistribution.

Conclusion

A large body of scientific evidence indicates that SFN is an effective anti-cancer agent. Despite extensive research in understanding the function and activity of SFN, little is known regarding the tissue distribution of SFN and its metabolites. The differences in bioavailability and distribution of specific metabolites to tissues could have a significant impact on efficacy and tissue-specific targets because SFN and its metabolites are known to work through multiple and potentially separate mechanisms of chemoprevention. These data are the first to show detailed SFN metabolism and tissue distribution profiles in mice. Herein we provide evidence that free SFN is not a major compound present in tissues of mice given SFN, but rather the glutathione, cysteinyl, and N-acetylcysteine conjugates of SFN are the most abundant. The kinetics of SFN metabolism and tissue distribution appears to follow what is observed in the plasma for most tissues except SI, colon and prostate. We also show that Nrf2 is not required for efficient metabolism and tissue distribution of SFN, and provide evidence for a gender difference in the Nrf2−/− mice, especially in response to higher doses of SFN. We report quantitative LC-MS/MS results in mice showing that the dietary anti-cancer agent SFN can be utilized in the diet and that its metabolites reach target tissues of carcinogenesis, such as colon and prostate.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Carmen Wong, Mohaiza Dashwood, Dr. Praveen Rajendran, Lydia Petell, Karin Hardin, Lauren Atwell and Dr. Laura Beaver for help with tissue collection and processing. Thanks to Jeff Morre for assistance with mass spectrometry. This work was supported in part the Environmental Health Science Center at Oregon State University (NIEHS P30 ES00210) and NIH grants (CA090890, CA122906, CA122959).

Abbreviations

- ARE

Antioxidant response element

- GSH

Glutathione

- GST

Glutathione-S-transferase

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- NF-E2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2

- Nrf2

related factor 2

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- SI

Small intestine

- SFN

Sulforaphane

- SFN-Cys

SFN-cysteine

- SFN-CG

SFN-cysteinyl-glycine

- SFN-GSH

SFN-glutathione

- SFN-NAC

SFN-N-acetylcysteine

- TBHQ

Tert-butylhyroquinone

- TFA

Trifluoroacetic acid

References

- 1.Steinbrecher A, Nimptsch K, Husing A, Rohrmann S, Linseisen J. Dietary glucosinolate intake and risk of prostate cancer in the epic-heidelberg cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(9):2179–2186. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang L, Zirpoli GR, Jayaprakash V, Reid ME, McCann SE, Nwogu CE, et al. Cruciferous vegetable intake is inversely associated with lung cancer risk among smokers: A case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(162):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang L, Zirpoli GR, Guru K, Moysich KB, Zhang Y, Ambrosone CB, et al. Intake of cruciferous vegetables modifies bladder cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 19(7):1806–1811. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seow A, Yuan JM, Sun CL, Van Den Berg D, Lee HP, Yu MC. Dietary isothiocyanates, glutathione s-transferase polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk in the singapore chinese health study. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(12):2055–2061. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.12.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P. Human metabolism and excretion of cancer chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of cruciferous vegetables. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7(12):1091–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higdon JV, Delage B, Williams DE, Dashwood RH. Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: Epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(3):224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke JD, Dashwood RH, Ho E. Multi-targeted prevention of cancer by sulforaphane. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(2):291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung KL, Kong AN. Molecular targets of dietary phenethyl isothiocyanate and sulforaphane for cancer chemoprevention. Aaps J. 2010;12(1):87–97. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwak M-K, Kensler TW. Targeting nrf2 signaling for cancer chemoprevention. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2010;244(1):66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Callaway EC. High cellular accumulation of sulphoraphane, a dietary anticarcinogen, is followed by rapid transporter-mediated export as a glutathione conjugate. Biochem J. 2002;364(Pt 1):301–307. doi: 10.1042/bj3640301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanlon N, Coldham N, Gielbert A, Kuhnert N, Sauer MJ, King LJ, et al. Absolute bioavailability and dose-dependent pharmacokinetic behaviour of dietary doses of the chemopreventive isothiocyanate sulforaphane in rat. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(3):559–564. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507824093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keum YS, Khor TO, Lin W, Shen G, Kwon KH, Barve A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of broccoli sprouts on the suppression of prostate cancer in transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (tramp) mice: Implication of induction of nrf2, ho-1 and apoptosis and the suppression of akt-dependent kinase pathway. Pharm Res. 2009;26(10):2324–2331. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasper AV, Al-Janobi A, Smith JA, Bacon JR, Fortun P, Atherton C, et al. Glutathione s-transferase m1 polymorphism and metabolism of sulforaphane from standard and high-glucosinolate broccoli. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(6):1283–1291. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu R, Khor TO, Shen G, Jeong WS, Hebbar V, Chen C, et al. Cancer chemoprevention of intestinal polyposis in apcmin/+ mice by sulforaphane, a natural product derived from cruciferous vegetable. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(10):2038–2046. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh SV, Warin R, Xiao D, Powolny AA, Stan SD, Arlotti JA, et al. Sulforaphane inhibits prostate Carcinogenesis and pulmonary metastasis in tramp mice in association with increased cytotoxicity of natural killer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2117–2125. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornblatt BS, Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Erb M, Fahey JW, Singh NK, et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of sulforaphane for chemoprevention in the breast. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(7):1485–1490. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saw CL, Huang MT, Liu Y, Khor TO, Conney AH, Kong AN. Impact of nrf2 on uvb-induced skin inflammation/photoprotection and photoprotective effect of sulforaphane. Mol Carcinog. 2010 doi: 10.1002/mc.20725. Published online ahead of print Dec 28 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jazwa A, Rojo AI, Innamorato NG, Hesse M, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Cuadrado A. Pharmacological targeting of the transcription factor nrf2 at the basal ganglia provides disease modifying therapy for experimental parkinsonism. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3731. Published online ahead of print March 28 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slatter JG, Rashed MS, Pearson PG, Han DH, Baillie TA. Biotransformation of methyl isocyanate in the rat. Evidence for glutathione conjugation as a major pathway of metabolism and implications for isocyanate-mediated toxicities. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;4(2):157–161. doi: 10.1021/tx00020a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Janobi AA, Mithen RF, Gasper AV, Shaw PN, Middleton RJ, Ortori CA, et al. Quantitative measurement of sulforaphane, iberin and their mercapturic acid pathway metabolites in human plasma and urine using liquid chromatography-tandem electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;844(2):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petri N, Tannergren C, Holst B, Mellon FA, Bao Y, Plumb GW, et al. Absorption/metabolism of sulforaphane and quercetin, and regulation of phase ii enzymes, in human jejunum in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(6):805–813. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myzak MC, Karplus PA, Chung FL, Dashwood RH. A novel mechanism of chemoprotection by sulforaphane: Inhibition of histone deacetylase. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5767–5774. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conaway CC, Krzeminski J, Amin S, Chung FL. Decomposition rates of isothiocyanate conjugates determine their activity as inhibitors of cytochrome p450 enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14(9):1170–1176. doi: 10.1021/tx010029w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conaway CC, Wang CX, Pittman B, Yang YM, Schwartz JE, Tian D, et al. Phenethyl isothiocyanate and sulforaphane and their n-acetylcysteine conjugates inhibit malignant progression of lung adenomas induced by tobacco carcinogens in a/j mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8548–8557. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang YM, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Schwartz J, Conaway CC, Halicka HD, Traganos F, et al. N-acetylcysteine conjugate of phenethyl isothiocyanate enhances apoptosis in growth-stimulated human lung cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8538–8547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang L, Li G, Song L, Zhang Y. The principal urinary metabolites of dietary isothiocyanates, n-acetylcysteine conjugates, elicit the same anti-proliferative response as their parent compounds in human bladder cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17(3):297–305. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiao JW, Chung FL, Kancherla R, Ahmed T, Mittelman A, Conaway CC. Sulforaphane and its metabolite mediate growth arrest and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2002;20(3):631–636. doi: 10.3892/ijo.20.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiao JW, Wu H, Ramaswamy G, Conaway CC, Chung FL, Wang L, et al. Ingestion of an isothiocyanate metabolite from cruciferous vegetables inhibits growth of human prostate cancer cell xenografts by apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(8):1403–1408. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung FL, Conaway CC, Rao CV, Reddy BS. Chemoprevention of colonic aberrant crypt foci in fischer rats by sulforaphane and phenethyl isothiocyanate. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(12):2287–2291. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.12.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Q, Battelli L, Hubbs AF. Multiorgan autoimmune inflammation, enhanced lymphoproliferation, and impaired homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in mice lacking the antioxidant-activated transcription factor nrf2. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(6):1960–1974. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackburn AC, Matthaei KI, Lim C, Taylor MC, Cappello JY, Hayes JD, et al. Deficiency of glutathione transferase zeta causes oxidative stress and activation of antioxidant response pathways. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(2):650–657. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai G, He L, Chou N, Wan YJ. Acetaminophen metabolism does not contribute to gender difference in its hepatotoxicity in mouse. Toxicol Sci. 2006;92(1):33–41. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chanas SA, Jiang Q, McMahon M, McWalter GK, McLellan LI, Elcombe CR, et al. Loss of the nrf2 transcription factor causes a marked reduction in constitutive and inducible expression of the glutathione s-transferase gsta1, gsta2, gstm1, gstm2, gstm3 and gstm4 genes in the livers of male and female mice. Biochem J. 2002;365(Pt 2):405–416. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen G, Kong AN. Nrf2 plays an important role in coordinated regulation of phase ii drug metabolism enzymes and phase iii drug transporters. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2009;30(7):345–355. doi: 10.1002/bdd.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anwar-Mohamed A, Degenhardt OS, El Gendy MA, Seubert JM, Kleeberger SR, El-Kadi AO. The effect of nrf2 knockout on the constitutive expression of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters in c57bl/6 mice livers. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.01.014. Published online ahead of print Jan 31 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khor TO, Huang MT, Kwon KH, Chan JY, Reddy BS, Kong AN. Nrf2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Cancer Res. 2006;66(24):11580–11584. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osburn WO, Karim B, Dolan PM, Liu G, Yamamoto M, Huso DL, et al. Increased colonic inflammatory injury and formation of aberrant crypt foci in nrf2-deficient mice upon dextran sulfate treatment. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(9):1883–1891. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khor TO, Huang MT, Prawan A, Liu Y, Hao X, Yu S, et al. Increased susceptibility of nrf2 knockout mice to colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1(3):187–191. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falkner KC, Pinaire JA, Xiao GH, Geoghegan TE, Prough RA. Regulation of the rat glutathione s-transferase a2 gene by glucocorticoids: Involvement of both the glucocorticoid and pregnane x receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60(3):611–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urquhart BL, Tirona RG, Kim RB. Nuclear receptors and the regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters: Implications for interindividual variability in response to drugs. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(5):566–578. doi: 10.1177/0091270007299930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kassahun K, Davis M, Hu P, Martin B, Baillie T. Biotransformation of the naturally occurring isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the rat: Identification of phase i metabolites and glutathione conjugates. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10(11):1228–1233. doi: 10.1021/tx970080t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]