Abstract

Objectives

To estimate trends over time in inpatient obstetric and gynecologic surgical procedures, and to estimate commonly performed obstetric and gynecologicsurgical procedures across a woman's lifespan.

Methods

Data were collected for procedures in adult women, 1979-2006 using the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), a federal discharge dataset of U.S. inpatient hospitals, including patient and hospital demographics and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure codes for adult women, 1979-2006. Age-adjusted rates per 1,000 women were created using 1990 U.S. Census data. Procedural trends over time were assessed.

Results

Over 137 million obstetric and gynecologic procedures were performed, comprising 26.5% of surgical procedures for adult women. Sixty-four percent were only obstetric and 29% were only gynecologic, with 7% of women undergoing both obstetric and gynecologic procedures during the same hospitalization. Obstetric and gynecologic procedures decreased from approximately 5,351,000 in 1979, to 4,949,000 in 2006. Both operative vaginal delivery and episiotomy rates fell, while spontaneous vaginal delivery and cesarean delivery increased. All gynecologic procedure rates fell during the study period, with the exception of incontinence procedures, which increased. Common procedures by age group differed across a woman's lifetime.

Conclusion

Inpatient obstetric and gynecologic procedures rates fell from 1979 to 2006. Inpatient obstetric and gynecologic procedure rates are decreasing over time, but still comprise a large proportion of inpatient surgical procedures for U.S. women.

Introduction

Women in the United States commonly undergo obstetric and gynecologic procedures, such as vaginal delivery, cesarean section, and hysterectomy during inpatient hospital stays. Little data exists regarding trends in these procedures. Rutkow, et al. published data in 1986 examining obstetric and gynecologic surgery trends from 1979 to 1984. According to this study, obstetric and gynecologic procedures comprised 5 of the top 10 most common surgical procedures in the United States. (1) Other studies have examined trends in specific gynecologic and obstetric procedure trends, but no study has looked at recent trends in overall procedures. (2,3,4)

The purpose of this study was to estimate trends over time in all major inpatient obstetric and gynecologic procedures using data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1979 to 2006. A second aim was to estimate principal inpatient Ob/Gyn surgical procedures performed across the lifespan of the U.S woman by decade of life year.

Material and Methods

Data were abstracted from the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), a federal dataset, utilizing a two-stage (1965-1987) and a three-stage (1988-2006) probability sampling of hospitals, followed by systematic random sampling of inpatient hospital discharges within these hospitals. Staging was designed to obtain representative distribution by geographical location, bed size, and type of ownership. The 1965 group of hospitals was followed through 1987 with periodic addition of new hospitals to replace those which closed or became ineligible. Using a similar approach, a new set of hospitals was selected in 1988. (5) Medical records from 466 non-federal short-stay hospitals (8% of all U.S. hospitals) were selected and approximately 270,000 discharges were collected per year from January 1979 to December 2006, the current publicly available time period. The survey recorded up to seven discharge diagnosis codes and four procedure codes, using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) coding system. Other de-identified information collected included patient sex, age, race, marital status, length of hospital stay, hospital size (number of beds), hospital ownership and insurance type or expected source of payment. Quality control programs have estimated the error rate for the NHDS at 4.3% for medical coding and data entry, and 1.4% for demographic coding and data entry. (6, 7)

After obtaining University of Pittsburgh, Institutional Review Board approval - Exempt status, women who underwent obstetric or gynecologic surgical procedures from 1979 to 2006 were identified using ICD-9-CM procedure codes. Table 1 lists the broad coding categories selected for study. All women undergoing one or more of these procedures were included in the analysis. Weights provided by NHDS for each patient discharge were used to tabulate surgical procedure numbers and demographics to allow inflation to national estimates. For subjects undergoing multiple procedures, these procedures were counted separately in their respective categories, but for multiple procedures under the same broader category, or for demographic data, an individual subject was tallied only once. Age-adjusted rates of procedures per 1000 women were calculated by the direct method of rate adjustment, using the 1990 projected United States Census population data for each year of age. Use of age-adjusted rates based on a standard population permitted examination of trends independent of changes in population age structure over time. Data from the 1990 U.S. Census was chosen to represent a midpoint in the study time period. Standard error of the age- adjusted rate was calculated by the method provided by NHDS. (5) When the estimated number of cases per year was based on fewer than 60 records in the database, the estimate was considered unreliable. (6)

Table 1. NHDS Codes for Obstetric and Gynecologic Procedures.

| Gyneologic Codes * | Description |

|---|---|

| 57 | Operations on urinary bladder ** |

| 65 | Operations on ovary |

| 66 | Operations on fallopian tube |

| 67 | Operations on cervix |

| 68 | Operations on uterus |

| 69 | Other operations on uterus and supporting structures |

| 70 | Operations on vagina and cul-de-sac |

| 71 | Operations on vulva and perineum |

| Obstetric Codes | |

| 72 | Forceps, vacuum, breech deliveries |

| 73 | Other procedures inducing or assisting delivery |

| 74 | Cesarean section |

| V27 | Outcome of delivery |

3 and 4 digit codes in each group were used to obtain more specific procedural data.

Urinary bladder procedures were limited to those performed by Gyn surgeons (i.e. cystoscopy and incontinence procedures).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

From 1979 to 2006, approximately 137,128,000 obstetric and gynecologic inpatient procedures were performed in the United States. Obstetric and gynecologic procedures comprised 26.5% of inpatient surgical procedures in adult women during the 28 year study time period. Table 2 lists the top ten most frequently occurring inpatient procedures, based on 3-digit ICD-9-CM procedural code classification, for years 1979 and 2006. In 1979 seven of these top ten procedures were obstetric or gynecologic in nature. In 2006, six of the top ten were obstetric and gynecologic in nature.

Table 2. Top surgical procedures by 3-digit code in U.S. women, 1979 and 2006.

| 1979 | 2006 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Procedure | Code | Procedure |

| 73.6 | episiotomy | 75.6 | repair of obstetric laceration |

| 69.0 | dilation and curetage | 74.1 | low transverse cesarean section |

| 68.4 | total abdominal hysterectomy | 73.5 | manually assisted delivery |

| 72.1 | low forceps w/pisiotomy | 99.0 | blood transfusion |

| 66.3 | other bilateral destruction/occlusion of fallopian tubes | 73.0 | artificial rupture of membranes |

| 74.1 | low transverse cesarean section | 75.3 | other intrauterine operation on fetus or amnion |

| 51.2 | cholestectomy | 38.9 | puncture of vessel |

| 57.3 | diagnostic procedure on bladder | 81.5 | joint replacement of lower extremity |

| 75.6 | repair of obstetric laceration | 73.4 | medical induction of labor |

| 45.2 | diagnostic procedure on large intestines | 45.1 | diagnostic procedure on small intestine |

Of the over 137 million identified procedures identified, 64% were solely obstetric and 29% solely gynecologic, with 7% of women undergoing both an obstetric and gynecologic procedure during the same inpatient admission. The mean age of women undergoing an obstetric procedure was 27 ± 6 years, and 39 ± 14 years for a gynecologic procedure. Overall length of hospital stay for obstetric procedures was 2.9 ± 4.8 days and for gynecologic procedures was 4.0 ± 4.8 days. Table 3 lists age and length of stay for women undergoing obstetric and gynecologic procedures by study year. Length of stay for cesarean section fell from 6.5 ± 3.5 days in 1979 to 3.6 ± 3.2 days in 2006. Length of stay for hysterectomy also fell from 8.5 ± 4.3 days in 1979 to 2.8 ± 3.5 days in 2006. The number of women undergoing inpatient obstetric and gynecologic procedures has decreased over time from 5,351,000 in 1979 to 4,949,000 in 2006. For gynecologic procedures, the number of procedures has decreased by 46%, from 2,852,000 in 1979 to 1,309,000 in 2006. For obstetric procedures, the number has increased 1.5-fold, from 2,755,000 in 1979 to 4,014,000 in 2006.

Table 3. Demographics for women undergoing Obstetric and Gynecologic procedures by year.

| Obstetric | Gynecologic | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years, ± SD) | ||

| 1979 | 25.6 (± 5.3) | 35.9 (± 13.0) |

| 1993 | 27.3 (± 5.6) | 40.0 (± 14.8) |

| 2006 | 27.8 (± 5.9) | 42.4 (± 14.8) |

|

| ||

| Length of stay (mean days, ± SD) | ||

| 1979 | 3.9 (± 2.9) | 4.9 (± 4.9) |

| 1993 | 2.5 (± 2.6) | 3.6 (± 5.6) |

| 2006 | 2.7 (± 2.3) | 2.9 (± 3.4) |

Figure 1 depicts trends over time of obstetric procedures using age-adjusted rates (AAR). AARs for spontaneous vaginal delivery have risen slightly, from 25.2 per 1000 women (±SE 1.58) in 1979 to 26.0 per 1000 women (±SE 1.63) in 2006. AARs for operative vaginal delivery have declined over 2-fold, from 6.1 per 1000 (±SE 0.47) in 1979 to 2.9 per 1000 (±SE 0.20) in 2006. Episiotomy AARs fell by over 75% during the study period, from 20.2 per 1000 (±SE 1.34) in 1979 to just 4.6 per 1000 (±SE 0.31) in 2006. Cesarean section AARs doubled over the time period, from 6.4 per 1000 (±SE 0.49) in 1979 to 13.5 per 1000 (±SE 0.86) in 2006.

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted rates of obstetric procedures in the United States, 1979-2006

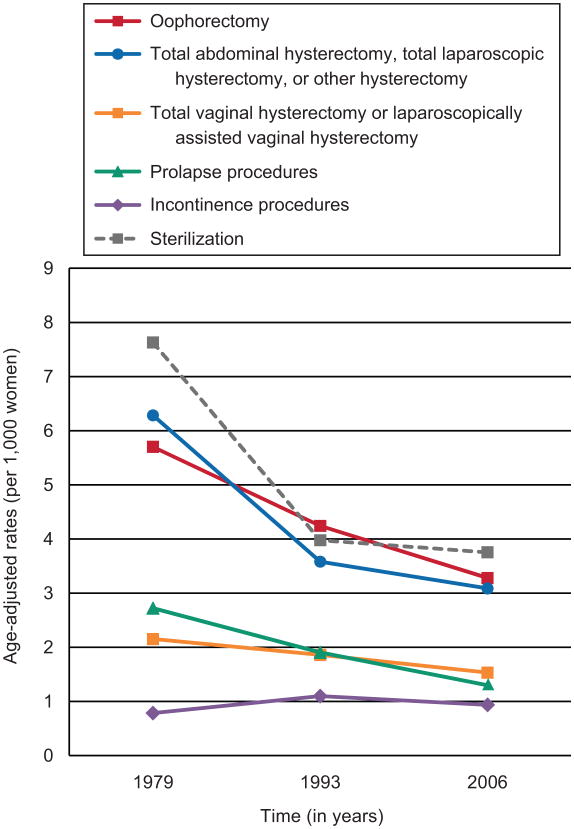

Overall AARs for gynecologic procedure fell during the study period, with the exception of procedures for stress urinary incontinence, which increased (Fig 2). AARs of abdominal and laparoscopic hysterectomies fell from 6.3 per 1000 women (±SE 0.49) in 1979 to 3.1 per 1000 (±SE 0.21) in 2006. AARs for vaginal hysterectomy declined from 2.2 per 1000 (±SE 0.19) in 1979 to 1.5 per 1000 (±SE 0.11) in 2006. AARs for oophorectomy fell from 5.7 per 1000 women (±SE 0.45) in 1979 to 3.3 per 1000 (±SE 0.22) in 2006. AARs for sterilization procedures fell by half, from 7.6 per 1000 (±SE 0.58) in 1979 to 3.8 per 1000 (±SE 0.26) in 2006. AARs of prolapse procedures fell from 2.7 per 1000 (±SE 0.24) in 1979 to 1.3 per 1000 (±SE 0.10) in 2006, while rates of incontinence procedures rose from 0.8 per 1000 (±SE 0.08) in 1979 to 0.9 per 1000 (±SE 0.08) in 2006.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted rates of gynecologic procedures in the United States, 1979-2006

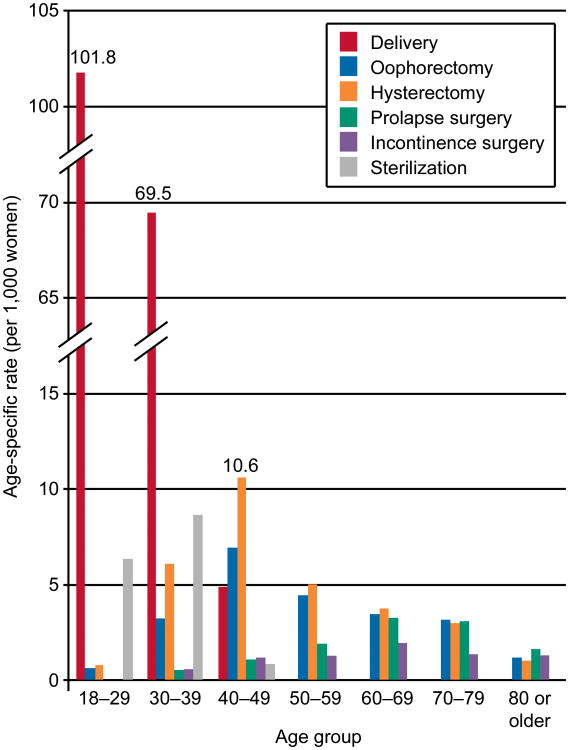

Figure 3 depicts procedures performed in 2006 in women divided into age by decade. The most common procedure performed in women aged younger than 40 was spontaneous vaginal delivery. For women age 40 to 69 years, the most common procedure was hysterectomy. In the 70 years and older group, the most commonly performed procedure was a repair for pelvic organ prolapse.

Figure 3.

Obstetric and gynecologic procedures by age group, 2006

Conclusions

Inpatient Gyn surgical procedures have decreased dramatically from 1979 to 2006, both with regard to total number of procedures and percentage of overall inpatient surgical procedures for adult women, while inpatient OB surgical procedures have increased. Overall, Ob/Gyn procedures still comprise a large proportion of overall surgical volume for adult women in the US. As expected, the type of surgery a woman is likely to undergo is strongly correlated with age and reproductive stage of life.

Surgeries traditionally performed by obstetrician/gynecologists comprised over 25% of inpatient surgical procedures for US women over the 27 year study period. In addition, out of all inpatient surgical procedures performed in women, Ob/Gyn-related procedures comprised the majority of the top 10 procedures across the study period. This dataset does not record surgeon subspecialty, therefore some of these traditionally Ob/Gyn procedures could have been performed by other subspecialists (i.e. Family Medicine, General Surgery). The decrease in inpatient gynecologic procedure trends over the study period likely reflects changing practice patterns, including increased utilization of minimally invasive outpatient surgeries and advances in medical treatments offered in place of surgery. (8) The overall rate of hysterectomy has decreased dramatically. In a recent study examining trends in hysterectomy with oophorectomy, the rate of hysterectomy alone decreased from 1979-2004. While the rate of hysterectomy with oophorectomy decreased in women <50 years old, the rate of hysterectomy with oophorectomy increased in women ≥50 years. (9,10) The rate of procedures for treatment of stress urinary incontinence increased over the study period and is likely due to the introduction of effective, minimally invasive procedures such as the synthetic midurethral sling. (3) This trend will likely continue as the proportion of the population affected by stress urinary incontinence is projected to increase dramatically over the next 30 years. (11) While the overall rate of surgical procedures for prolapse decreased, surgical repair of prolapse was the most common inpatient procedure performed in women >70 years of age. Jones et al, in a recent study of surgical treatment of prolapse procedures, noted decreasing rates in women <52 years, while in women ≥52 years the rates remained stable, likely reflecting the true rate of prolapse procedures in the US. (12)

While operative vaginal delivery procedure rates have dramatically decreased, rates of cesarean section increased considerably. Martin et al. showed that the rate of cesarean delivery has increased steadily since 1996, reaching a record 31.1% in 2006. (13) The dramatic increase in the cesarean delivery rate likely reflects changing obstetric practice patterns, including a rise in the rate of primary cesarean delivery, a decline in the rate of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC), and a decline in the utilization of operative vaginal delivery. Studies have shown a dramatic decrease in use of episiotomy and operative vaginal deliveries which appears to inversely correlate with rising cesarean delivery rates, possibly representing physicians' route of delivery choice for more difficult deliveries. (13,14) The fall in rates of episiotomy may also reflect practice changes due to recognition of increased rates of posterior perineal trauma with routine episiotomy use. (15)

The US adult female population is estimated to increase by nearly 50% by 2050. (16) Current projections estimate that the Ob/Gyn physician workforce will only increase by only 15% by 2020. (17) In 1996 there were 38,424 U.S. physicians registered by specialty type as Ob/Gyn, increasing to only 42,333 in 2006. Despite an overall increase in the number or Ob/Gyn physicians over the study time period, the number of Ob/Gyns relative to the total population has not changed significantly since 1994. According to American Medical Association data, the number of Ob/Gyns per 10,000 U.S. citizens was 14.1 in 1994, remaining 14.1 per 10,000 in 2006 (range 14.1-14.7). (17) While overall inpatient surgical procedures, specifically gynecologic procedures, have decreased over time, obstetric and certain gynecologic procedures have increased. It is crucial to maintain an adequate OB/GYN subspecialist workforce to provide essential surgical services to our female patients.

These data are based on cross-sectional sampling and are dependent upon both accuracy of coding and generalizability of the sampling. The NHDS data have been shown to have reasonable coding accuracy. (6) We chose U.S. Census data from 1990, a time point midway through the study, to calculate the age-adjusted rates. Census data from 1990 may not accurately reflect year to year population change. However, data from a single year was needed to base and compare age-adjusted rates across the entire study time span. We recognize that the 1988 NHDS sampling redesign may have influenced the overall trends, however, examination of frequencies for each year by procedure (data not shown) revealed no consistent change in rates from 1987 to 1988.

Additionally, the NHDS underestimates the number of surgical procedures in US women as it does not collect data from same-day surgeries or ambulatory surgical centers. The lack of data on same-day surgeries will continue to affect the accuracy of estimates of total U.S. surgical procedures as an increasing number of surgical procedures are being performed on an outpatient basis. The National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery (NSAS), a federal database similar to the NHDS, collected data on ambulatory surgical procedures from 1994 to 1996 and was then discontinued. The NSAS was reinstituted during 2006 for a one year period. Continued ambulatory surgical data collection, in addition to inpatient data collection, is needed to accurately assess future surgical trends.

The NHDS provides a large sample size, well-defined inclusion criteria, and standardized use of diagnosis and procedure codes. Though inpatient Ob/Gyn procedures rates fell from 1979 to 2006; Ob/Gyn procedures still represent a large proportion of surgical volume for women in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grant Number UL1 RR024153 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented as a poster at the 30th Annual American Urogynecologic Society Scientific Meeting. Hollywood, FL, Sept 24-26, 2009.

References

- 1.Rutkow IM. Obstetric and gynecologic operations in the United States, 1979 to 1984. Obstet Gynecol. 1986 Jun;67(6):755–9. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozak LJ, Weeks JD. U.S. trends in obstetric procedures, 1990-2000. Birth. 2002 Sep;29(3):157–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliphant SS, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Trends in stress urinary incontinence inpatient procedures in the United States, 1979-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;200(5):521–e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frankman EA, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Episiotomy in the United States: has anything changed. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;200(5):573–e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.022. Epub 2009 Feb 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 1979-2006 Multi-year Public Use Data File Documentation. 2008 July; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennison C, Pokras R. Design and operation of the National Hospital Discharge Survey: 1988 redesign. Vital Health Stat. 2000;1(39) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Health Statistics Reports: 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. 2008 July;(No. 5) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Apr 19;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003855.pub2. CD003855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowder JL, Oliphant SS, Ghetti C, Burrows LJ, Meyn LA, Balk J. Prophylactic bilateral oophorectomy or removal of remaining ovary at the time of hysterectomy in the United States, 1979-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;202(6):538.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.030. Epub 2010 Jan 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Koonin LM, Morrow B, Kieke BA, Wilcox LS. Hysterectomy surveillance--United States, 1980-1993. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1997 Aug 8;46(4):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luber KM, Boero SB, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: Current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1496–1503. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones KA, Shepherd JP, Oliphant SS, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Trends in Inpatient Prolapse Procedures in the United States, 1979-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;202(5):501.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.017. Epub 2010 Mar 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menacker F, Martin JA. BirthStats: rates of cesarean delivery, and unassisted and assisted vaginal delivery, United States, 1996, 2000, and 2006. Birth. 2009 Jun;36(2):167. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankman EA, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Episiotomy in the United States: has anything changed. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;200(5):573.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.022. Epub 2009 Feb 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroli G, Belizan J. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1999 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000081. CD000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Census Bureau. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2000-2050. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- 17.American Medical Association. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US. 1997/8-2008 USA: AMA; [Google Scholar]