Abstract

This randomized, controlled study (N = 256) was conducted to compare three interventions designed to promote hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination completion among clients undergoing methadone maintenance (MM) treatment. Participants were recruited from five MM treatment sites in Southern California and randomized into three groups: Motivational Interviewing-Single (MI-Single), Motivational Interviewing-Group (MI-Group); and Nurse-Led Hepatitis Health Promotion (HHP). All were offered the 3-series HAV/HBV vaccine. A total of 148 participants completed the vaccine. Groups did not differ in rate of vaccination completion (73.6%, HHP group, versus 65% and 69% for the MI-Single, and MI-Group, respectively). The equivalence of findings across groups suggests the value of including nurses with a comprehensive health focus in promoting vaccination completion.

Keywords: Hepatitis A and B, Methadone Maintained, Nurse, Health Promotion

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination continues to be a challenge among drug users (Quaglio et al., 2002), with HBV prevalence rates ranging from 40-81% (Amesty et al., 2008). Injecting drug users (IDUs) are often very mobile, dropping in and out of treatment; this may compromise HBV series vaccination compliance (Budd, Robertson, & Elton, 2004). Lack of knowledge or information has been cited as one reason IDUs may not complete the HBV vaccination series (Seal et al., 2003). Lack of perceived risk for the development of infectious disease also may compromise compliance (Van Herck, Leuridan, & van Damme, 2007). Despite the risk, drug users rarely complete the 3-dose HBV vaccination program (Rogers & Lubman, 2005). Researchers have shown that accelerated HBV vaccination schedules, such as may be possible in treatment programs, can improve completion rates in this population (Graham & McClean, 2007; Lum et al., 2008; Rogers & Lubman).

Few investigators have examined the impact of enrollment in a methadone maintenance (MM) treatment program on vaccine completion (i.e., whether compliance is improved). These clients are at high risk for hepatitis, thus, MM treatment programs are logical sites for providing HBV vaccination. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relative effectiveness of three interventions designed to promote HAV/HBV vaccination completion among MM treatment-clients: Motivational Interviewing (delivered either on a one-to-one basis or as a group therapy) versus a Nurse-Led Hepatitis Health Promotion Program. In addition to comparing the effects of these three programs, other sociodemographic, psychosocial, and behavioral predictors of vaccination completion were identified.

Vaccination Compliance

Several investigators have examined factors associated with HBV vaccination completion among drug users including sociodemographic factors such as age, resources, education, gender, and access to care. HBV vaccination completion has been associated with older age, having public assistance as a main income source (Ompad et al., 2004), having access to health care, and having a higher level of education (Yee & Rhodes, 2002).

In studies of the impact of gender on HBV vaccine compliance, females were more likely than males to receive hepatitis vaccination (Chen & Cantrell, 2006) and African-American females were more likely than males to complete hepatitis vaccination programs (Middleman, 2004. Nyamathi, Liu, et al. (2009) found that, among a group of homeless adults, the majority of whom were substance abusers, HBV vaccine completers were more likely to be African-American females with fair or poor health.

When behavioral factors such as sexual practice, type of drug use, motivation/self-efficacy, and participation in a treatment program were considered, Rhodes, Grimley, and Hergenrather (2003) found that among men who have sex with men (MSMs), those with a higher level of self-efficacy were most likely to complete HBV vaccination. Increased levels of self-efficacy also were associated with HBV vaccination compliance among African-American MSMs living in the Deep South (Rhodes & DiClemente, 2003). Baars et al. (2008) found that injecting drug use (rather than frequency of drug use or type of drug used) was associated with vaccine completion, and demonstrated that drug users who were motivated to receive a vaccination were more likely to actually obtain vaccination at some point in the future. Moreover, individuals who were enrolled at any time in a drug treatment program were more likely to be vaccinated against HBV compared with those who never attended such a program (Kuo, Sherman, Thomas, & Strathdee, 2004).

A few investigators have studied program site as a factor related to vaccine completion and have demonstrated that vaccination can be effectively delivered to drug-using populations through several venues. For example, HBV vaccination was cost-effective in terms of disease and societal cost prevention when delivered at syringe exchange sites (Hu et al., 2008). HBV vaccination completion rates were high among groups of non-MM treatment drug users attending public health drug treatment centers in Italy (Quaglio et al., 2002). Other investigators have examined the impact of vaccine completion among persons who are enrolled in MM programs and have suggested that MM programs are an ideal place to provide HBV vaccination as these settings require frequent attendance (Lugoboni, Quaglio, Civitelli, & Mezzelani, 2009). For example, Borg et al. (1999) reported a compliance rate of 86% for all three HBV doses among MM clinic attendees in New York City. The study was small (N = 43) but the authors concluded that their results provide evidence of the feasibility of HBV vaccination at MM clinics.

Motivational Interviewing

A number of approaches have proven successful in reducing health risks in vulnerable populations. Motivational interviewing (MI), for example, is a client-oriented counseling style (Miller & Rollnick, 2009) applied to various areas of health behavior change, including reduction of alcohol use, in a variety of populations (Deas, 2008; Peterson, Baer, Wells, Ginzler, & Garrett, 2006). One of the theoretical models providing the academic framework upon which MI is based is the transtheoretical model of change (Treasure, 2004). According to this model, personal readiness to make change can be divided into five stages: precontemplation (not ready to think about change seriously); contemplation (ready to think about change); determination (preparing to make plans for change); action (implementing change); and maintenance (ensuring that behavioral change becomes habitual; Treasure; Woody, DeCristofaro, & Carlton, 2008). It has been suggested that MI is most useful when treating patients in the early stages of change (precontemplation and contemplation; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005).

Currently, little is known about the utilization of MI techniques for enhancement of HBV vaccination in MM settings and how it compares to nurse-led health promotion strategies. As MI has been shown to be effective for the reduction of substance abuse among people with a history of chemical dependence (Bradley, Baker, & Lewin, 2007), whether delivered on a one-to-one basis (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007) or as group therapy (LaBrie, Thompson, Huchting, Lac, & Buckley, 2007; Santa Ana & Wulfert, 2007), it may be a valuable approach to promoting completion of the HAV/HBV vaccination series. In terms of cost efficiency, the effectiveness of MI delivered either individually or in groups also needs investigation. To our knowledge, no studies to date assess the impact of MI on vaccine completion among this population using either individual- or group-delivered MI.

Nurse-Led Intervention

A number of investigators have shown that nurse-led health promotion programs are effective in reduction of substance abuse (Cummings, Francescutti, Predy, & Cummings, 2006; Fleming, Lund, Wilton, Landry, & Scheets, 2008; Tsai, Tsai, Lin, & Chen, 2009). Stringer, Ratcliffe, and Gross (2006) found that a nursing educational intervention providing HBV education to pregnant teenagers resulted in a high HBV vaccination acceptance rate (91%). Nurse-led interventions have resulted in high HBV vaccination acceptance rates among genitourinary clinic patients (Handy, Pattman, & Richards, 2006). Most recently, Nyamathi, Liu, et al. (2009) showed that the provision of nurse case management can significantly improve HBV vaccination compliance among homeless adults.

In this study, the nurse-led intervention targeting factors that may impact vaccine completion was guided by the comprehensive health seeking and coping paradigm (CHSCP; Nyamathi, 1989), adapted from a stress and coping paradigm of Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Schlotfeldt's (1981) health-seeking paradigm. These factors include sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and access to care; cognitive factors such as perceived health status and knowledge of hepatitis; psychosocial factors such as depressive symptomotology, poor emotional well being, and social support; and receipt of nursing intervention (such as HHP) and behavioral change (reduction of alcohol and drug use).The study builds upon an earlier vaccination study (Nyamathi, Liu, et al., 2009) by examining the effect of nurse case management on vaccination completion among a cohort of persons attending MM treatment.

Research Questions

The following research questions were investigated:

What is the relative effectiveness of each of three interventions (Motivational Interviewing-Single, Motivational Interviewing-Group, and Nurse-Led Hepatitis Health Promotion, in promoting HAV/HBV vaccination completion among MM treatment-clients?

Which of a set of sociodemographic, cognitive, psychosocial, intervention, and behavioral factors are predictors of vaccination completion in the study sample?

The Twinrix vaccine administered included vaccines for HAV and HBV, because although the disease burden for HAV is almost half that of HBV, with estimated new cases of HAV at 25,000 per year compared to HBV at 43,000 cases per year, HAV is one of the most reported diseases in the US (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2009). Furthermore, high risk individuals, including injection and non-injection drug users, men having sex with men, and people with chronic liver disease, are at risk for fulminant Hepatitis A (Fiore, Wasley, & Bell, 2006).

Method

A randomized controlled trial was undertaken to study the impact of the three-group intervention on HAV/HBV vaccine completion with 256 adults attending MM treatment at 6- month follow-up after program initiation. The three programs included: Motivational Interviewing-Single (MI-Single), Motivational Interviewing-Group (MI-Group), and Nurse-Led Hepatitis Health Promotion (HHP).

Sample and Setting

The 256 adults receiving MM treatment were randomized into one of three intervention programs at each of five study sites. Sample size was determined by a priori power estimates reflecting 80% power to detect a significant reduction in alcohol use in these adults at follow-up with alpha = .05. Inclusion criteria for MM treatment participants were: (a) had received methadone for at least 3 months; (b) age range 18-55 years; and (c) reported moderate-to-heavy alcohol use based on questions from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992). A total of 21 (8%) participants were lost to follow-up at 6 months.

As seen in Table 1, the sample was approximately balanced in gender and was predominantly African American or Latino. Most of the participants had completed high school. A small percentage of participants were employed. Recruitment was conducted in five MM treatment sites in Southern California that provided outpatient methadone to qualified adults.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Behavioral Characteristics of Overall Sample and by Completion of HAV/HBV Vaccine.

| Characteristics | Overall | Vaccine Completion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 148) | Yes (n = 103) |

No (n = 45) |

|

| Demographic Factors: | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) |

| Age | 46.3 (4.2) | 51.2 (0.8) | 53.3(1.1) |

| % | % | % | |

| Male | 55.0 | 55.3 | 53.3 |

| Group: | |||

| MI-Single | 35.3 | 32.0 | 37.8 |

| MI-group | 29.3 | 29.1 | 28.9 |

| HHP | 35.3 | 38.8 | 33.3 |

| Ethnicity: | |||

| African American | 51.0 | 50.5 | 55.6 |

| White | 13.3 | 13.6 | 6.7 |

| Latino | 30.5 | 33.0 | 26.7 |

| Other | 5.3 | 2.9 | 11.1 |

| High School Grad | 81.5 | 77.7 | 88.9 |

| Partnered | 55.6 | 56.3 | 55.6 |

| Employed* | 16.7 | 21.4 | 6.8 |

| Recruitment Site: * | |||

| Site A | 5.3 | 1.0 | 8.9 |

| Site B | 30.5 | 37.9 | 15.6 |

| Site C | 10.6 | 12.6 | 6.7 |

| Site D | 35.1 | 31.1 | 46.7 |

| Site E | 18.5 | 17.5 | 22.2 |

| Social Characteristics: | |||

| Fair/poor health | 58.3 | 43.7 | 40.0 |

| Childhood Physical Abuse | 24.5 | 25.2 | 20.0 |

| Behavioral Factors: | |||

| Lifetime Trade Sex | 36.0 | 33.0 | 40.0 |

| Recent marijuana use | 15.9 | 15.5 | 13.3 |

| Recent IDU | 34.4 | 33.0 | 33.3 |

| Smoke > 1 pack/day | 28.5 | 27.2 | 31.1 |

| Psychological Resources | 62.3 | 60.2 | 64.4 |

| Depressive Sxs | 82.8 | 83.5 | 80.0 |

| Poor Emotional Well Being | 64.2 | 66.0 | 57.8 |

| Social Support From: | |||

| Primarily Drug Users | 8.2 | 5.8 | 4.4 |

| Primarily Non Drug Users | 53.7 | 63.1 | 77.8 |

| Both | 38.1 | 29.1 | 17.8 |

| No One | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 |

| Readiness to Change: | |||

| Stage of Change | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) |

| Pre-contemplation | 10.28 (0.23) | 10.30 (0.26) | 10.43 (0.47) |

| Contemplation | 22.32 (0.31) | 22.25(0.38) | 22.50 (0.60) |

| Preparation | 3.68 (0.07) | 3.63 (0.09) | 3.80 (0.12) |

| Action | 10.65 (0.18) | 10.60 (0.22) | 10.80 (0.31) |

| Maintenance | 14.21 (0.22) | 14.20 (0.09) | 14.22 (0.34) |

| Intent to Adhere: | % | % | % |

| Easy (to get vaccine) | 94.0 | 95.2 | 90.9 |

| Want (to get vaccine) * | 96.0 | 98.1 | 90.9 |

| Likely (to get vaccine) * | 96.0 | 98.1 | 90.9 |

significant difference between completers and non-completers is p <.05

Procedure

The study and associated materials were approved by the university Human Subject Protection Committee. The study was announced by means of approved study flyers, which were posted at the MM sites. Interested MM clients reported to the research staff located at each site for detailed information and initiation of a 2-minute screening. After informed consent was reviewed and signed in a private room, trained research staff administered a brief structured questionnaire composed of socio-demographic characteristics, a screen for alcohol use and severity, and a hepatitis-related health history. Upon successful completion of the screening, detailed information was provided about the study to eligible persons and a second-level consent for blood testing was obtained. MM clients who met eligibility criteria and wished to participate further completed a third consent form prior to enrollment.

For all eligible clients a structured baseline questionnaire was administered by the research staff. Clients were then randomized to one of the three programs by means of a computerized randomization program. Each program involved three sessions as well as the HAV/HBV vaccination series for all those found to be HBV seronegative. The first vaccine dose was administered approximately 1 week after baseline, when results of anti-HBV HBs were obtained, and thereafter at 1 month and 6 months after the first dose.

The MI sessions were delivered by two master's or doctorally prepared therapists specialized in the facilitation of MI; each of the therapists remained with their clients for completion of the sessions. The Nurse-led HHP sessions were delivered by a licensed vocational nurse (LVN) trained in research and a trained research staff assistant. The three sessions were scheduled 2 weeks apart and generally administered over a 6-week period. A detailed treatment manual was followed for consistency to protocol, carefully monitored by the project director. Baseline data were collected from February 2007 to May 2008. Follow-up data were collected 6 months later. An incentive of $10 was provided to all participants after completion of each of the sessions. An incentive was not provided for completing the vaccine doses.

Measures

Socio-demographic information, collected by a structured questionnaire, included age, gender, birth date, ethnicity, education, childhood physical abuse, history of substance abuse treatment, and lifetime history of trading sex. Responses were measured as yes/no.

HAV/HBV Vaccination Status was assessed by completion of all three doses of the Twinrix vaccine. Completion of each dose was logged onto the completion form by the nurse.

Perceived Health Status was measured on a 5-point scale from excellent to poor, with health status dichotomized at fair/poor versus better health. This one item has been extensively used with general populations as well as impoverished and drug-addicted subsamples as a valid indicator of general health (Koegel & Burnam, 1991; Wenzel, Leake, & Gelberg, 2000). A dichotomous item also inquired about past 6-month hospitalization by a yes/no response.

Stages of change (Miller & Tonigan, 1996) were characterized by: pre-contemplation (sum of 4 items); contemplation (sum of 6 items); action (sum of 3 items); maintenance (sum of 4 items), and preparation (1 item) based on an 18-item stage of change scale. The Stages of Change instrument was modified to assess behavior change in relation to hepatitis vaccine completion as well as alcohol reduction as a part of the larger study. Three subscales of the instrument used included Ambivalence, Recognition, and Taking Steps. Test-retest reliabilities of these subscales were .82, .88, and .91, respectively; as measured by intraclass correlation; .83, .94, and .93, respectively (as measured by Pearson's correlation).

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff, 1977), which has been validated for use in homeless populations (Nyamathi, Christiani, Nahid, Gregerson, & Leake, 2006; Nyamathi et al., 2008). The 10-item self-report instrument is designed to measure depressive symptomology in the general population (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994) and measures the frequency of a symptom on a 4-point response scale from 0 Rarely or None of the time (Less than 1 day) to 4 All of the time (5-7 days). Scale scores were dichotomized at a cutoff value of 8, a frequently used figure to suggest depressive symptomatology. The internal reliability of the scale in this sample was .80.

Emotional well-being was measured by the 5-item Mental Health Index (MHI-5); this scale has well-established reliability and validity (Stewart, Hays, & Ware, 1988). Scores were linearly transformed so that they ranged from 0 to 100. A cut-point of 66 (Rubenstein et al., 1989) was used to discriminate participants' emotional well-being. Cronbach's alpha for the scale in this study was .79.

Social support was measured by a 9-item scale used in the RAND Medical Outcomes Study (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). The items elicit information about how often respondents had friends, family, or partners available to provide them with support such as food, and a place to stay, on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The instrument has demonstrated high convergent and discriminant validity; internal consistency reliability coefficients range from .91 to .97 for the subscales (Sherbourne & Stewart). Cronbach's alpha for the scale in this study was .94. An additional question inquired about whether social support came primarily from drug users, non-drug users, or both.

Alcohol use was assessed by the Time Line Follow Back (Babor, Steinberg, Anton, & Del Boca, 2000), which assesses the number of standard drinks consumed per day over the last 30 days.

Drug use was measured by the Addiction Severity Index – Lite Version. This measure is a shortened version of the ASI (McLellan et al., 1992). Calculation of composite scores from the ASI questionnaire was based on scoring procedures for the ASI interview outlined in McGahan, Griffith, and McLellan (1986). Drug use was dichotomized at its median for clarity of presentation in this study.

Intervention

HHP Program

At baseline, an LVN-prepared nurse and research assistant conducted three time-equivalent (60 minute) HHP group sessions delivered within 6 weeks of entry into the program in a private area at the MM site. The average number of participants was 6 (range = 5-7).

The HHP sessions focused on hepatitis education, specifically, the progression of HCV infection and the behaviors that infected individuals can adopt to prevent or reduce accumulated damage to liver functioning. Behaviors include primarily avoiding all alcohol and other drugs, receiving the HAV/HBV vaccine series, eating a balanced diet, lessening dangers of reinfection of HCV by not resuming injection drug use (IDU), not receiving unsafe tattoos and body piercing, not engaging in unprotected sexual behavior, and being consistent in engaging in other health-related behaviors such as regular medical check-ups. Strategies for enhancing coping with addiction also were provided.

Motivational Interviewing Program (Individual vs. Group)

Three 60-minute sessions were delivered (one-on-one or via group format) by trained MI specialists with the same delivery timing and number of clients in the group session as in the HHP sessions. The trainers included a PhD-prepared psychologist who conducted most of the MI-group sessions and a MSW-prepared researcher who conducted most of the individual MI sessions. MI sessions were focused on exploring the impact alcohol use had on health and risky behaviors, and working through ambivalence towards reducing alcohol use while focusing on subsequent life goals. The health threat of hepatitis B and C also was interwoven in terms of behaviors that could reduce these risk factors, as hepatitis can further negatively impact liver function. Healthy behaviors including receiving the HAV/HBV vaccine were addressed. Content in the group vs. one-on-one MI sessions was identical.

Regardless of group, both MI and HHP sessions were preceded by a needs assessment and included referrals and appointments as needed for medical and mental health services. All participants received a small incentive for each of three sessions ($10); and a Local Community Resource Guide. For both MI and HHP programs, subsequent to the sessions the first of the three-series HAV/HBV vaccine was administered by the research nurse, if the participant was eligible for the vaccine (HBV sero-negative and no history of allergies) and desired to be vaccinated. All participants also received referrals to 12-step alcohol treatment programs in the community. In addition, participants were notified to return for their 6-month follow-up questionnaire, and for those receiving the vaccine series, the last vaccine dose.

Data Analysis

All analyses were per-protocol (PPA), an analysis in which only patients who complete the entire clinical trial were analyzed. The outcome variable of interest was vaccine completion. Differences between completers and non-completers were studied by different program types as well as by demographic, social, and behavioral characteristics. Chi-square tests and Fisher's exact tests were used to assess statistical differences in completion among categorical variables. T-tests for normally distributed continuous variables and non-parametric Wilcoxon's rank-sum tests for non-normal continuous variables were conducted to detect significant differences between completers and non-completers. Backward multiple logistic regression analysis was used to create a model for vaccine completion. Predictors included variables that were associated with vaccine completion at the .15 level in preliminary analyses; covariates were retained if they were significant at the .10 level. Although there was no evidence of any statistically significant differences in program types with respect to vaccine completion, they were included in the final logistic regression model because that was conceptually an important variable. All assumptions were checked and met. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS/STAT.

Results

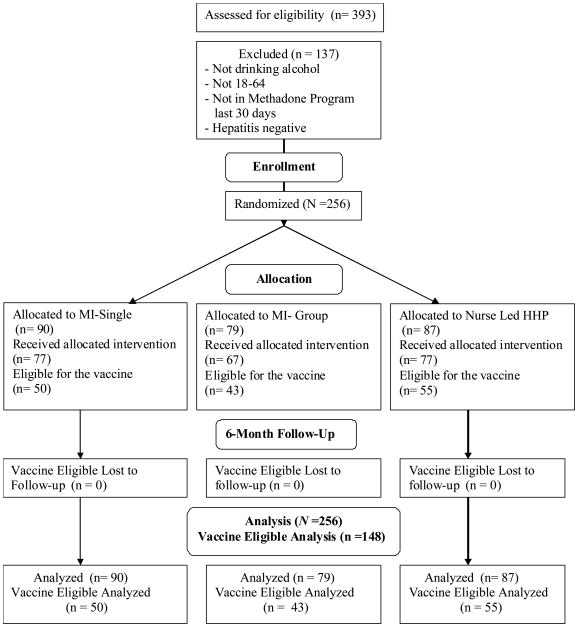

Characteristics of the overall sample as well as by completers and non-completers are shown in Table 1. One hundred forty eight out of the total of 256 MM treatment participants (58%) were eligible for vaccination and were spread evenly among the MI-S, MI-G and HHP (See Figure 1). About 39% of the vaccine completers were in the HHP group, while 29% were in the MI-S group and 31% in the MI-G group. The distribution of completers among groups was not statistically significant. About one-third of participants received social support from both drug-users and non-drug users, while almost half reported social support from primarily non drug users (differences by group non-significant).

Figure 1.

Revised template of the CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through each stage of a randomized trial.

The five different sites used in the study were labeled Sites A-E.; among these, Site D had the largest proportion of non-completers and Site C the lowest (p = .006). Significant differences were noted on measures of self-efficacy: 98% of the completers wanted to get vaccinated at baseline compared to 90% among non-completers. The same pattern was observed when they were asked how likely they were to get vaccinated. No statistical differences were noted between groups on stages of change: both completers and non-completers showed similar distributions of pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

Associations between vaccine completion and improvements in cognitive and social characteristics are shown in Table 2. A significant difference in HBV knowledge improvement was observed between completers and non-completers (p = .05). No differences were noted among vaccine completers vs. non completers in terms of improvement in either mental health, less alcohol consumption, or fewer depressive symptoms.

Table 2. Improvements in Selected Variables by Vaccine Completion Among Methadone Maintained Clients by Program.

| Improvement at 6 months compared to baseline |

Completed (n = 103) |

Not Completed (n = 45) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |

| Mental Health | 12.89 (2.30) | 9.78 (3.94) |

| Total days of alcohol use in last 30 days | -6.26 (1.52) | -2.49 (2.27) |

| CES-D score | -3.46 (0.72) | -1.87 (1.21) |

| Average daily alcohol consumption | -3.18 (0.57) | -2.53 (1.38) |

| ASI medical status | -0.08 (0.04) | -0.19 (0.06) |

| ASI drug subscale score | -0.04 (0.01) | -0.04 (0.01) |

| HBV knowledge+ | 4.10 (0.30) | 3.01 (0.51) |

| HCV knowledge | 4.77 (0.32) | 4.12 (0.48) |

| SEI score | 0.37 (0.15) | 0.31 (0.27) |

| Social support | 1.99 (1.19) | 2.11 (1.66) |

| Total alcohol use in last 30 days | 67.80 (16.98) | 44.25 (30.31) |

Note: Negative values imply the characteristic was LESS present at 6 month follow-up compared to baseline.

Significant difference between groups is p < .05.

Table 3 shows the distribution of non-vaccine completers (overall sample as well as by program type) by all the reasons cited as to why they did not complete the vaccines. The results of this table are descriptive; statistical tests were not performed due to the small number of non- completers in the sample citing any reason for not completing the vaccines. The primary reason cited was that they simply did not want to take the vaccine. Many (29.6%) felt that the risk was “not great” for not taking the vaccine, indicating a lack of awareness among non-completers of the risks of HBV and HCV. Reasons for not completing vaccines were cited more often by the MI-S and MI-G program participants than those in the Nurse-led program.

Table 3. Reasons for Not Completing Vaccine by Program Types (n = 45).

| Overall | Program MI-S |

Program MI-Group |

Program Nurse-led |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Constraint | % | % | % | % |

| No transportation to vaccine appointment | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 |

| No Time to go | 4.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| No Child care | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Working | 4.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Job/school | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Attending to something more important | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Preference | % | |||

| Don't want to go to clinic | 4.6 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Don't want vaccination | 52.3 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 15.9 |

| Hepatitis not serious | 9.1 | |||

| Risk is not great | 29.6 | |||

| Physical Constraint | % | |||

| Too many worries | 11.4 | 4.6 | 6.8 | 0.0 |

| Physical illness keeps from making to clinic | 9.1 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Alcohol/Drug keeps from making to clinic | 6.8 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 0.0 |

| Forgetfulness | 4.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Meds made sick | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Table 4 shows the results of a logistic regression analysis treating vaccine completion as the outcome. Significant predictors were employment status and improvement in HBV knowledge, after adjusting for program types and participants intent to adhere at baseline (factors such as how easy/difficult they felt it would be to get the vaccination as well as how compliant/or-not they would be to actually complete the vaccine series). Those who were not employed had one-third the odds of completing the vaccination compared to the odds of employed persons. Similarly, those who showed greater improvement in HBV knowledge at 6 months were more likely to complete the vaccination compared to those who did not show as much knowledge improvement. In particular, with each unit increase in HBV knowledge, the odds of completing the vaccination series increased by 36%. Vaccination completion rates did not differ by group. Participants who believed at baseline that it would be hard for them to get vaccination (various reasons cited, shown in Table 3) were not less likely to actually complete the vaccination, but those who declared at baseline that they were not likely to get the vaccination tended to be less likely to complete vaccination.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Predictors of Vaccine Completion among Methadone Maintained adults (n = 146)

| Estimated β | SE (est. β) | Estimated OR |

95% CI (for OR) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||

| MI-Single vs HP | 0.12 | 0.29 | 1.003 | 0.37 - 2.73 | 0.68 |

| MI-group vs HP | -0.23 | 0.27 | 0.70 | 0.27 – 1.80 | 0.38 |

| Unemployed (vs employed) | -.67 | 0.33 | 0.26 | (0.07, 0.99) | 0. 04 |

| Intent to Adhere: | |||||

| Hard (to get vac.) vs easy | -0.16 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.15 – 3.45 | 0.68 |

| Not likely (to comply) vs likely | -0.78 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.03 – 1.33 | 0.09 |

| HBV Knowledge at 6 months | 0.31 | 0.10 | 1.36 | (1.11, 1.66) | 0.003 |

Discussion

Vaccination completion rates among MM clients were positively affected by the provision of either one-to-one MI, group MI, or Nurse-led hepatitis health promotion. Our HAV/HBV completion rates were 65%, 69%, and 74%, respectively. Compliance rates among IDUs in our study were similar or superior to those reported in other studies. For example, Campbell et al. (2007) found that among IDUs receiving a first HBV vaccination, only 41% received a second dose and 14% received a third dose. Ompad et al. (2004) likewise reported that only 41% of clients completed all three doses.

Compliance rates generally have been studied using IDU participants not attending MM treatment. Monetary incentives (Seal et al., 2003), vaccination provided at syringe exchange sites (Altice, Bruce, Walton, & Buitrago, 2005), and accelerated vaccination (Macdonald, Dore, Amin, & van Beek, 2007) have resulted in vaccination completion rates among drug users ranging from 21%-77%. Our results provide new information in that they pertain to a subsample of IDU participants who are attending MM treatment and show that in this subgroup, vaccination rates were generally higher compared with rates for non-MM treatment groups reported by others. It may be that HBV vaccination compliance among persons attending MM treatment is enhanced because this group is already motivated to seek medical attention for other health concerns (i.e., drug abuse).

We found that employment status was significantly associated with vaccination completion. In contrast, other investigators have not shown employment status to be predictive of vaccination among IDU samples (Baars et al., 2008; Nyamathi, Liu, et al., 2009). It is important to note that these prior studies were not specific to drug users also attending MM treatment. Our findings suggest that interventions that provide education might be most effective among drug users seeking MM treatment who also are employed.

There were significant differences regarding completion rates among the various treatment sites. The sites differed in terms of location, and this may have had an impact on vaccination completion. Nevertheless, all sites served clients receiving MM treatment and had similar hours of operation. Further, all sites readily embraced this research study. The differences may relate to the fact that the sites where there were the most completers had better communication follow-up with the researchers than the others. This resulted in enhanced reminders provided to participants that a vaccine dose was due.

Provision of HBV knowledge significantly affected vaccination completion rates, and this finding is supported by the literature. Lack of education has been cited as a barrier to HBV vaccination adherence among IDUs (Seal et al., 2003), while programs that offer targeted education support HAV/HBV vaccination adherence (Nyamathi, Liu, et al., 2009). School-based initiatives offering HBV education also have demonstrated that compliance can be improved by the provision of knowledge (Middleman, 2004). Focus group interviews of clients receiving hepatitis-related services have revealed that participants themselves believe that education should be a key ingredient of hepatitis prevention (Rainey, 2007).

In addition to our finding that non-completers had less knowledge about HBV than completers, we found that the participants' knowledge level played a role in deciding whether or not to initiate vaccination. That is, some of our non-completers reported that they did not feel themselves to be at particular risk for the development of HBV infection and, consequently, declined taking the vaccination. This is consistent with other findings showing that knowledge is positively associated with the decision to seek HBV vaccination. (Baars et al., 2008). Moreover, ongoing knowledge of HBV as well as a better appreciation of the relationship of risk behaviors to perceived risk may promote a greater degree of HBV completion among clients attending MM treatment programs.

Limitations

The study has a number of limitations. One is that our control variables were assessed by self-report, which is associated with bias. Another is that the study was conducted in one geographical area, Southern California, which may represent different types of MM treatment populations compared to cities in other geographical areas. Finally, we used a convenience sample of participants attending MM treatment. This sample may not be fully representative of the total MM treatment population.

Conclusion

The effects of three different interventions (single MI, group MI and Nurse-Led HHP) on HAV/HBV vaccination completion were examined in MM clients. Although being employed and provision of knowledge to clients were associated with vaccination completion, supporting earlier research, perhaps the most interesting finding of this trial was the fact that the three interventions equally resulted in good completion rates among the participants. Although the efficacy of nurse-led interventions in the promotion of HAV/HBV vaccination compliance has been established (Nyamathi, Liu, et al., 2009; Nyamathi, Sinha, et al., 2009), this is the first documentation that a nurse-led hepatitis intervention was as effective as a non-nurse run MI. Thus, investigating the cost effectiveness of interventions delivered by basic trained nurses compared to masters- or doctorally-prepared MI therapists is of interest. In addition, there are cost implications in the equivalence found between group-focused interventions (nurse-led and MI) and individual-led sessions MI in MM sites. As nurses educate, counsel, and refer MM participants who have concomitant medical conditions, the comprehensive attention to health and behavior change makes the nurse, whose focus can be broader than just methadone treatment dosing, a valuable member of the MM team.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, #AA015759

Contributor Information

Adeline Nyamathi, Associate Dean for International Research and Scholarly Activities, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing.

Karabi Sinha, Statistician, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing.

Barbara Greengold, Research Associate, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing.

Allan Cohen, Director of Research and Training, Bay Area Addiction, Research and Treatment, Inc., Los Angeles, CA.

Mary Marfisee, Adjunct Associate Professor, University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine.

References

- Altice FL, Bruce RD, Walton MR, Buitrago MI. Adherence to hepatitis B virus vaccination at syringe exchange sites. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:151–161. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amesty S, Ompad DC, Galea S, Fuller CM, Wu Y, Koblin B, et al. Prevalence and correlates of previous hepatitis B vaccination and infection among young drug-users in New York City. Journal of Community Health. 2008;33:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baars J, Boon B, De Wit JB, Schutten M, van Steenbergen JE, Garretsen HF, et al. Drug users' participation in a free hepatitis B vaccination program: Demographic, behavioral and social-cognitive determinants. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:2145–2162. doi: 10.1080/10826080802344609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton RF, Del Boca FK. Talk is cheap: Measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg L, Khuri E, Wells A, Melia D, Bergasa NV, Ho A, et al. Methadone-maintained former heroin addicts, including those who are anti-HIV-1 seropositive, comply with and respond to hepatitis B vaccination. Addiction. 1999;94:489–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9444894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley AC, Baker A, Lewin TJ. Group intervention for coexisting psychosis and substance use disorders in rural Australia: Outcomes over 3 years. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:501–508. doi: 10.1080/00048670701332300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd J, Robertson R, Elton R. Hepatitis B vaccination and injecting drug users. British Journal of General Practice. 2004;54:444–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JV, Garfein RS, Thiede H, Hagan H, Ouellet LJ, Golub ET, et al. Convenience is the key to hepatitis A and B vaccination uptake among young adult injection drug users. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(Suppl):S64–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon L, Carey M, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Disease burden from viral hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. 2009 http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics.htm#section3.

- Chen H, Cantrell CR. Prevalence and factors associated with self-reported vaccination rates among US adults at high risk of vaccine-preventable hepatitis. Current Medical Research & Opinion. 2006;22:2489–2492. doi: 10.1185/030079906X154088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings GE, Francescutti LH, Predy G, Cummings G. Health promotion and disease prevention in the emergency department: A feasibility study. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2006;8:100–105. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500013543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D. Evidence-based treatments for alcohol use disorders in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl. 4):S348–354. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Mortality & Morbidity Weekly Report. 2006;55(RR-7):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Lund MR, Wilton G, Landry M, Scheets D. The healthy moms study: The efficacy of brief alcohol intervention in postpartum women. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2008;32:1600–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D, McClean H. Yorkshire regional audit of hepatitis B vaccination. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2007;18:212–214. doi: 10.1258/095646207780132460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy P, Pattman RS, Richards J. ‘I’m OK?' Evaluation of a new walk-in quick-check clinic. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2006;17:677–680. doi: 10.1258/095646206780071027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Grau L, Scott G, Seal KH, Marshall P, Singer M, et al. Economic evaluation of delivering hepatitis B vaccine to injection drug users. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel P, Burnam MA. Course of homelessness among the seriously mentally ill. National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored study; Rockville, MD: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo I, Sherman SG, Thomas DL, Strathdee SA. Hepatitis B virus infection and vaccination among young injection and non-injection drug users: Missed opportunities to prevent infection. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2004;73:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. pp. 117–180. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Thompson AD, Huchting K, Lac A, Buckley K. A group motivational interviewing intervention reduces drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences in adjudicated college women. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2549–2562. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugoboni F, Quaglio G, Civitelli P, Mezzelani P. Bloodborne viral hepatitis infections among drug users: The role of vaccination. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health. 2009;6:400–413. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6010400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum PJ, Hahn JA, Shafer KP, Evans JL, Davidson PJ, Stein E, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and immunization status in a new generation of injection drug users in San Francisco. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2008;15:229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald V, Dore G, Amin J, van Beek I. Predictors of completion of a hepatitis B vaccination schedule in attendees at a primary health care centre. Sexual Health. 2007;4(1):27–30. doi: 10.1071/sh06008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahan PL, Griffith JA, McClellan AT. Composite scores From the Addiction Severity Index. Philadelphia, PA: Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleman AB. Race/Ethnicity and gender disparities in the utilization of a school-based hepatitis B immunization initiative. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behavioral & Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;37:129–140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers' motivation for change: The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A. Comprehensive health seeking and coping paradigm. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1989;14:281–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi AM, Christiani A, Nahid P, Gregerson P, Leake B. A randomized controlled trial of two treatment programs for homeless adults with latent tuberculosis infection. International Journal of Tuberculosis & Lung Disease. 2006;10:775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, de Castro V, McNeese-Smith D, Nyamathi K, Shoptaw S, Marfisee M, et al. Alcohol use reduction program in methadone maintained individuals with hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2008;27(4):27–30. doi: 10.1080/10550880802324499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Liu Y, Marfisee M, Shoptaw S, Gregerson P, Saab S, et al. Effects of a nurse-managed program on hepatitis A and B vaccine completion among homeless adults. Nursing Research. 2009;58:13–22. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181902b93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Sinha K, Saab S, Marfisee M, Greengold B, Leake B, et al. Feasibility of completing an accelerated vaccine series for homeless adults. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2009;16:666–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ompad DC, Galea S, Wu Y, Fuller CM, Latka M, Koblin B, et al. Acceptance and completion of hepatitis B vaccination among drug users in New York City. Communicable Disease & Public Health. 2004;7:294–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PL, Baer JS, Wells EA, Ginzler JA, Garrett SB. Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:254–264. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglio G, Talamini G, Lugoboni F, Lechi A, Venturini L, Jarlais DC, et al. Compliance with hepatitis B vaccination in 1175 heroin users and risk factors associated with lack of vaccine response. Addiction. 2002;97:985–992. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey J. An evaluation of a state hepatitis prevention and control program: Focus group interviews with clients. Health Promotion Practice. 2007;8:266–272. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, DiClemente RJ. Psychosocial predictors of hepatitis B vaccination among young African-American gay men in the deep south. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30:449–454. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200305000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Grimley DM, Hergenrather KC. Integrating behavioral theory to understand hepatitis B vaccination among men who have sex with men. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:291–300. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers N, Lubman DI. An accelerated hepatitis B vaccination schedule for young drug users. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2005;29:305–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Calkins DR, Young RJ, Cleary P, Fink A, Kosecoff J, et al. Improving patient function: A randomized trial of functional disability screening. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1989;111:836–842. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-10-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana E, Wulfert E. Efficacy of group motivational interviewing (GMI) for psychiatric inpatients with chemical dependence. Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:816–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotfeldt R. Nursing in the future. Nursing Outlook. 1981;29:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Kral AH, Lorvick J, McNees A, Gee L, Edlin BR. A randomized controlled trial of monetary incentives vs. outreach to enhance adherence to the hepatitis B vaccine series among injection drug users. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE., Jr The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer M, Ratcliffe S, Gross R. Acceptance of hepatitis B vaccination by pregnant adolescents. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2006;31:54–60. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J. Motivational interviewing. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2004;10:331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y, Tsai M, Lin Y, Chen CY. Brief intervention for problem drinkers in a Chinese population: A randomized controlled trial in a hospital setting. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2009;33:95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Herck K, Leuridan E, van Damme P. Schedules for hepatitis B vaccination of risk groups: Balancing immunogenicity and compliance. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:426–432. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL, Leake BD, Gelberg L. Health of homeless women with recent experience of rape. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:265–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.04269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody D, DeCristofaro C, Carlton BG. Smoking cessation readiness: Are your patients ready to quit? Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20:407–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee LJ, Rhodes SD. Understanding correlates of hepatitis B virus vaccination in men who have sex with men: What have we learned? Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78:374–377. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.5.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]