Abstract

Here we demonstrate complex networks of CD8 T-cell cross-reactivities between influenza A virus (IAV) and Epstein- Barr virus (EBV) in humans and between lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and vaccinia virus (VV) in mice. We also show directly that cross-reactive T-cells mediate protective heterologous immunity in mice. Subsets of T-cell populations reactive with one epitope cross-reacted with either of several other epitopes encoded by the same or the heterologous virus. Human T-cells specific to EBV-encoded BMLF1280-288 could be cross-reactive with two IAV or two other EBV epitopes. Mouse T-cells specific to the VV-encoded a11r198-205 could be cross-reactive with three different LCMV, one Pichinde virus, or one other VV epitope. Patterns of cross-reactivity differed among individuals, reflecting the private specificities of the host’s immune repertoire, and divergence in the abilities of T-cell populations to mediate protective immunity. Defining such cross-reactive networks between commonly encountered human pathogens may facilitate the design of vaccines.

Keywords: Vaccinia virus, Epstein Barr virus, influenza A virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, memory CD8 T-cells, cross-reactivity, heterologous immunity, infectious mononucleosis

INTRODUCTION

Established memory T-cell responses to a previously encountered pathogen can have a major impact on the course and outcome of a subsequent infection with an unrelated pathogen. This phenomenon, known as heterologous immunity, is dependent on the sequence of virus infections and can be either beneficial or detrimental to the host (1-6). Some HLA-A2+ patients with EBV-associated infectious mononucleosis (IM) have T-cell responses cross-reactive between the influenza A (IVA) M158-66 epitope and the immunodominant EBV-BMLF1280-288 epitope, suggesting that the CD8 T-cell response in IM includes memory T-cells cross-reactive with previously encountered viruses (5). Fulminant hepatitis during hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been associated with T-cell responses dominated by cross-reactivity between HCV and a second influenza epitope, NA231-239 (4).

There are numerous examples of heterologous immunity in mouse models. For example, a history of LCMV infection predisposes to both protective immunity and altered immunopathology upon challenge with VV (7, 8). Some of these mice develop panniculitis in their visceral fat, with a pathology resembling human erythema nodosum, a form of panniculitis that has been reported following human smallpox vaccination. During VV infection of LCMV-immune mice there are proliferative expansions of T-cells specific to any one of three different LCMV epitopes, NP205-212, GP34-41, or GP118-125 (9). Adoptive transfer of these LCMV-immune splenocytes from one mouse into three naïve congenic hosts resulted in all three mice expanding the same LCMV-epitope-specific population upon VV infection, thereby demonstrating private specificity in the cross-reactive memory T-cell repertoire in each individual donor. Using the concept of molecular mimicry as a premise for identifying potential cross-reactive epitopes between LCMV and VV, (10) we found two H-2Kb-restricted VV epitopes that had 50% sequence similarity to LCMV-NP205-212, VV-e7r130-137 and VV-a11r198-205 (11). Evidence to date is consistent with the concept that reactivated cross-reactive memory T-cells mediate heterologous immunity, but this has yet to be definitely established (7, 12).

Many reports have described epitope-specific T-cell responses that can cross-react with another single epitope (3-5, 12-15). Here we demonstrate, first within human and then within murine CD8 memory T-cell pools, that one epitope can stimulate T cell populations that contain subsets which cross-react with either of several different epitopes encoded by the same or heterologous viruses. Each individual has a cross-reactivity network which is, in part, determined by the history of prior infections and the resultant changes in private specificities of their memory TCR repertoires. In the murine infection model, which is more amenable to manipulation, we demonstrate how the sequence of virus infection influences cross-reactive patterns and also for the first time demonstrate that cross-reactive T-cells can mediate protective heterologous immunity.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b) and B6.SJL-ptprca (LY5.1) congenic male mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY), respectively. Mice were used at 2 to 8 months of age. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Animal Medicine.

Cell lines

ATCC vero cells were used in plaque assays. The TAP-2 deficient B6-derived T lymphoma cell line (RMA-S), provided by H.-G. Ljunggren (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm), was grown in RPMI. As stimulators for CD8 T-cell lines, RMA-S cells were incubated with 1 μM peptide for 1 h at 37°C and then irradiated (3,000 Rad) and washed before adding to culture. All cell lines were supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, and 10% heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 min) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). All cell lines were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium unless otherwise stated (MEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Viruses

The Western Reserve (WR) strain of VV, a DNA virus in the orthopoxvirus family, was propagated in L929 cells (16). LCMV (Armstrong strain) and PV (AN3739 strain), RNA viruses in the Old World and New World arenavirus families, respectively, were propagated in BHK21 baby hamster kidney cells (16). The mouse-adapted IAV A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), a RNA virus in the orthomyxovirus family, was grown in the allantoic fluid of 10-day old embryonated chicken eggs (SPAFAS, Preston CT) (17).

Infection protocols

Mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 104 PFU of LCMV, 106 PFU VV and 2 × 107 PFU PV, and metofane-anesthetized mice were challenged i.n. with 70 PFU of IAV A/PR/8/34. To control for culture contaminants, VV and PV stocks were purified through a sucrose gradient and diluted in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and LCMV was diluted more than 40-fold in HBSS. Mice were considered immune 6 weeks or later after infection. Control naïve mice were either left uninoculated or else were inoculated with tissue culture media or HBSS. The control mice were always age matched to the experimental group and housed exactly the same in pathogen-free conditions.

Virus titration

VV titers in 10% tissue homogenate from each organ (fat pads, testes) were determined by plaque assays on ATCC vero cells, as described elsewhere (8).

Identification and screening for potential cross-reactive VV epitopes

We searched for VV epitopes which could generate cross-reactive T-cell responses with the H-2Kb-restricted LCMV-NP205 epitope (YTVKYPNL) (18). We restricted our search of the VV genome using the DNA/RNA and Protein analysis software DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering Company, Ltd) to 8-mers which maintained the H-2Kb binding motif and had 30% or more sequence similarity to LCMV-NP205.. These studies are described in more detail elsewhere (11). Two H-2Kb-restricted epitopes were identified, one in the VV protein e7r, positions 130-137 (STLNFNNL) and the second in the VV protein a11r, positions 198-205 (AIVNYANL). In addition, LCMV epitopes NP396, Db (FQPQNGQFI), GP34, Db (KAVYNFATC), GP34, Kb (AVYNFATC), GP276, Db (SGVENPGGYCL), GP118, Kb (ISHNFCNL), PV epitope NP205, Kb (YTVKFPNM) (12, 18-21), IAV epitope NP366 Db (ASNENMETM) (22), and ovalbumin epitope OVA 257-264, Kb (SIINFEKL) were used. These synthetic peptides were obtained from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA), purified with reverse phase-high pressure liquid chromatography to 90% purity.

Cell surface and tetramer staining by flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from splenocytes, peritoneal exudates (PEC), or peripheral blood. Erythrocytes were lysed with 0.84% NH4Cl solution. FACS staining was done as previously described in 96-well plates with fluorochrome-labeled mAbs, PerCP-anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7) and FITC-anti-CD44 (clone IM7). Tetramer-staining was done as previously described using phycoerythrin (PE) and/or allophycocyanin (APC) labeled tetramers (23). Samples were analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer (San Jose, CA) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, OR). All surface mAbs were purchased from BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA. MHC class I peptide tetramers specific for VV-e7r130/Kb, VV-a11R198/Kb, LCMV-NP205/Kb, LCMV-NP396/Db, LCMV-GP118/Kb, and LCMV-GP34/Kb were prepared as previously described (23).

Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS)

Cells (106) were stimulated either with medium, 5 μM synthetic peptide, 5 μg/ml anti-CD3 (145-2C11) or 105 VV-infected cells (MC57G), as previously described (23). Intracellular cytokine-producing cells were detected with PE- labeled anti-IFNγ and APC- labeled anti-TNFα mAbs. IgG-isotype mAbs were used in the same assay. The mAbs were purchased from BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA. The samples were analyzed as described above.

In vitro expansion of antigen-specific CD8 T-cell lines

Splenocytes (107) from VV- or LCMV-immune mice were co-cultured with 1μM peptide-pulsed RMA-S cells (106) in RPMI supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% FBS for 4 to 5 days at 37°C at 5% CO2. As stimulators for CD8 T-cell lines, RMA-S cells were incubated with 1 μM peptide for 1 h at 37°C and then irradiated (3,000 Rad) and washed before adding to culture. The IL-2 culture supplement BD T-Stim (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was added after 4 to 5 days of culture. Peptide stimulation was repeated every 4 to 5 days. After 20 to 25 days of stimulation (4-5 stimulations) lines were analyzed. TCR Vβ mRNA expression of the L/a11r-4 and L/a11r-5 T-cell lines stimulated with a11r-peptide were examined. The a11r-specific T-cell lines were purified with lympholyte-M and then RNA was isolated. RT-PCR was performed with specific primers for the indicated Vβ-families, as described elsewhere (23).

Adoptive transfer of antigen-specific T-cells into mice

T-cell lines were rested without peptide stimulation for 7 days. Thereafter, live cells were separated with lympholyte-M (Cedarlane, Hornby, Can.). T-cells were suspended in HBSS at 107 cells/ml and incubated with 2 μM CFSE for 15 min at 37°C. After incubation cells were washed twice with HBSS, and 106 cells injected i.p. into recipient mice. Mice were infected with 106 PFU VV i.p. on the same day. Mice were sacrificed day 3 to 4 post infection. Fat pads and/or testes were analyzed for VV titers, as these organs had the highest titers for the longest time (11). PECs were analyzed for immune responses and for division of transferred T-cells. Surface staining was performed as described above with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies, PerCP-anti-CD45.2 (LY5.2, clone 104) and APC-anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7). Transferred donor cells were identified as positive for CD45.2 and CD8 when congenic mice were used.

SMART-RACE PCR analysis of the CD8 Repertoire

Cells from the CD8 T-cell lines were revived from cryopreservation and washed in complete media. To extract RNA 106 live cells were subjected to the Trizol method of RNA extraction according to manufacturers protocol (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA.). cDNA was synthesized using the SMART Race cDNA amplification kit from Clontech using a modified manufactures protocol. In place of kit provided powerscript for cDNA sythesis, Superscript III was used. To amplify the TCR-beta specific genes the Advantage2 system was used according to manufacture’s protocol (Clontech). For the 5′ forward primer the Universal Primer Mix from the SMART Race cDNA amplification kit was used. To amplify the genes of interest a 3′ reverse primer specific to the TCR-beta region was used and reported previously (23). The PCR amplification program used was provided in manufactures protocol. The resulting PCR product of appropriate size (~500-700 bp) was gel purified using NucleoSpin Extract II kit according to manufacture’s protocol (Clontech). Purified PCR product was ligated into pCR4 vector from the TOPO TA cloning kit (invitrogen) according to manufacture’s protocol and transformed into DH5□ E. coli from One Shot TOP10 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen) using manufacture’s procedures. Colonies were selected and amplified overnight for sequencing. Amplified colonies were then preserved in 20% glycerol on dry ice and sent to Agencourt Bioscience for sequencing. Resulting sequences were aligned using Sequencher and analysed using IMGT/V-quest (http://www.imgt.org) (Nucl. Acids Res, 37, D1006-D1012 (2009); doi:10.1093/nar/gkn838. PMID: 18978023)(Nucl. Acids Res, 36, W503-508 (2008). PMID: 18503082)

Human Subjects

Influenza A virus-immune patients with acute EBV infection between the ages of 18-23 were volunteers from the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Student Health Services at Amherst, MA. HLA-typing was performed using the Lymphotype Class I system (Biotest Diagnostics) and an Olerup SSP kit (GenoVision). Acute EBV infection was confirmed by a monospot test and the detection of capsid-specific IgM in patient sera. Positive staining with HLA-A2-tetramers loaded with influenza-M1 was used as an indication that these individuals had been exposed to influenza A virus in the past. Patients provided up to eight blood samples (50 ml each) starting at presentation with IM (Day 0), then weekly for the following 6 weeks, and then again at 1 year. Healthy donors between the ages of 24-50 were volunteers from the research community at UMass Medical School (Worcester, MA). HLA status and immunity to EBV and influenza A virus were assessed using monoclonal antibody (BB7.2, Becton Dickinson (BD)) and tetramer stains, respectively. Previous exposure to EBV was confirmed by the detection of capsid-specific IgG in donor sera. Donors provided up to three blood samples (60 ml each). This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at UMass Medical School.

Blood preparation and bulk human T-cell culture

PBMC were isolated and cultured as previous described (5). Briefly, PBMC were isolated using Ficoll-paque plus (Amersham Bioscience) and were stained with anti-CD8 microbeads before being positively selected using the Miltenyi Biotech MACS system. CD8+ lymphocytes were plated at 2.5 × 105 per ml together with peptide-pulsed (1 μM), irradiated (3000 RAD) T2 cells (ATCC #CRL-1992) at 5 × 104 per ml in 4 ml total volume per well of a 12-well plate. T-cell lines were fed media [AIM-V (Gibco) supplemented with 14% human AB serum (Nabi), 16% MLA-144 supernatant, 10 U/ml rIL-2 (BD), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco), 0.5% beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 1% HEPES (Hyclone)] every 3-4 days and were re-stimulated with T2 cells weekly. We did most of our in vitro studies after only three to four stimulations as in this range we found the T cell repertoire of our antigen-specific population to closely resemble the in vivo repertoire (unpublished data). After 6 stimulations there is more skewing of the antigen-specific repertoires for some antigens but not all. Our design was to get as close to an approximation of the antigen-specific TcR repertoire in vivo prior to stimulation. Since we only do 3-4 stimulations the culture does not become 100% tetramer+ or high affinity cells. There most likely is a polyclonal population that has a range of affinities to the stimulating ligand. Frequently, cells in the culture will produce cytokines such as MIP1β in response to cognate ligand and yet not bind the cognate tetramer (5).

HLA-A2-restricted peptides

The following peptides were synthesized to >90% purity by Biosource: EBV-BMLF1280-288 (GLCTLVAML), IAV-M158-66 (GILGFVFTL), tyrosinase (YMNGTMSQV), EBV-BRLF-1190-198 (YVLDHLIVV), EBV-LMP-2329-337 (LLWTLVVLL), IAV-NP85-94 (KLGEFYNQMM) (5, 24-28).

Human MHC-Class I tetramers

A detailed description of the protocol used by the tetramer facility at UMass Medical School has been previously published (5). Tetramers were assembled using the above peptide sequences for EBV-BMLF1 and influenza-M1 and were conjugated to PE (Sigma), APC (Caltag), or Quantum Red (Sigma). Tetramers assembled with tyrosinase (Immunomics) were used as a negative control, and non-specific staining was not observed.

Human extracellular and intracellular staining

Cells were plated at 106 per well and washed with staining buffer (PBS, 2% FCS, 1% sodium azide). Tetramers were added to cells and incubated at room temperature for 40 min, washed off, and the cells were fixed with FACS Lysing Solution (BD). For ICS, cells first incubated at 37C with 5uM peptide and brefeldin A (Golgi Plug, BD) for 5hrs before being stained with tetramer as described above. Cells were permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were stained with anti- IFNγ (B27, BD) monoclonal antibody for 30min at 4C. Isotype control antibodies did not stain positive. Samples were read on FACS Calibur (BD).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are expressed as mean values ± standard errors of the mean. Comparisons between groups were performed with the unpaired t test (two tailed).

RESULTS

Cross-reactive T-cell networks in humans: T-cell populations specific to three unrelated antigens can cross-react with a single EBV epitope

The demonstration that some individuals expand cross-reactive T-cells that recognize both EBV-BMLF1280 and influenza A M158 peptides supports the concept that the lymphoproliferation characteristic of infectious mononucleosis includes cross-reactive memory CD8 T-cells activated by EBV (5). Due to its large genome, EBV could encode an extensive pool of T-cell epitopes cross-reactive with memory T-cells of other specificities. Here, by using tetramer staining of freshly isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes and peptide-stimulated cell lines to identify these new cross-reactive T-cell responses (5), we define a pattern of cross-reactivities involving several EBV and influenza A epitopes (Table 1A). Our studies focused on the EBV-BMLF1280 epitope, against which 100% of HLA-A2+ individuals mount a CD8 T-cell response during the acute phase of EBV infection (24). T-cell lines derived from 5 out of 16 donors and cultured with either influenza A M158 or EBV-BMLF1280 peptide recognized both the influenza A M158 and EBV-BMLF1280 epitopes with a relatively equal estimated avidity (5). Such cross-reactivity was not originally predicted, since influenza A M158 shares only 3 of 9 amino acids in common with the EBV-BMLF1 epitope (Table 1A). This confirms our earlier report (5), but here we show that EBV-BMLF1-specific T-cells could also recognize other epitopes.

Table 1.

CD8 T-cell epitopes that participate in cross-reactive responses

| A) HLA-2-restricted human CD8 T-cell epitopes that generate cross-reactive responses to EBV BMLF-1280 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epitope | Amino acid (aa) sequence and position | % of aa in common with EBV BMLF-1280 |

|||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| EBV BMLF-1280 | G | L | C | T | L | V | A | M | L | 100% | |

| EBV BRLF-1190 | Y | V | L | D | H | L | I | V | V | 0% | |

| EBV LMP-2329 | L | L | W | T | L | V | V | L | L | 55.6% | |

| IV M158 | G | I | L | G | F | V | F | T | L | 33.3% | |

| IV NP85 | K | L | G | E | F | Y | N | Q | M | M | 10% |

| B) H2Kb-restricted murine CD8 T-cell epitopes that generate cross-reactive responses to VV a11r198 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epitope | Amino acid (aa) sequence and position | % of aa in common with VV a11r198 |

|||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| VV a11r198 | A | I | V | N | Y | A | N | L | 100% |

| LCMV GP118 | I | S | H | N | F | C | N | L | 50% |

| LCMV GP34 | A | V | Y | N | F | A | T | C | 37.5% |

| LCMV NP205 | Y | T | V | K | Y | P | N | L | 50% |

| PV NP205 | Y | T | V | K | F | P | N | M | 25% |

| VV e7r130 | S | T | L | N | F | N | N | L | 37.5% |

| OVA257 | S | I | I | N | F | E | K | L | 37.5% |

Bold aa are common with EBV BMLF-1280

Bold aa are common with VV a11r198

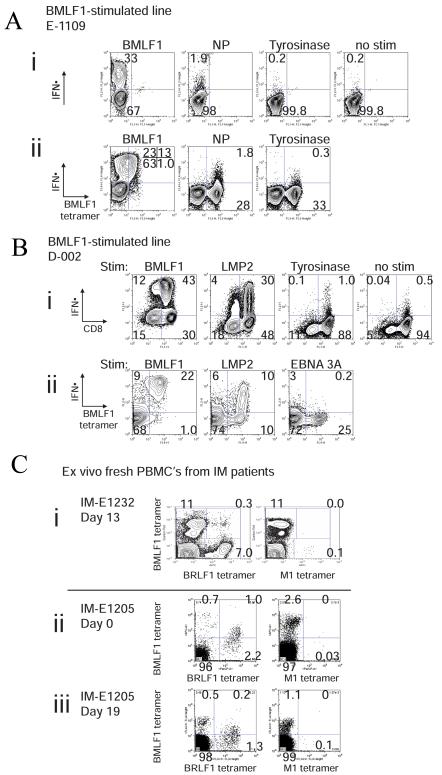

EBV-BMLF1-specific T-cell lines derived from IM patients could contain a discrete population of T-cells which also recognized the influenza A NP85-epitope. Figure 1A demonstrates the results for one of these individuals, where 2% of the CD8 T-cells produced IFNγ in response to stimulation with the subdominant influenza A NP85 epitope (Fig 1Ai). This influenza A NP85-responding population co-stained with EBV-BMLF1280-tetramer (Fig 1Aii). Control T-cell lines, derived from the same donors and grown in the absence of the EBV-BMLF1280 peptide or stimulated with IVA-M158, did not include a similar subset of influenza A-NP85-responsive cells; this suggests that the growth of these cross-reactive T-cells in culture was dependent on the EBV-BMLF1280 peptide.

Figure 1. Cross-reactive T-cell responses in humans.

(A) Cross-reactive T-cells with specificity for EBV-BMLF1280 and IAV-NP85. CD8 T-cells derived from IM patient E1109 were cultured with BMLF1 peptide-pulsed T2 cells for 4-5 weeks. (i) The antigen specificity of the cell line was tested in a standard intracellular cytokine assay, where the cell line was restimulated for 5hr with a variety of different peptides. The percentage represents the proportion of the T-cell line producing IFNγ. (ii) A similar intracellular cytokine assay was combined with extracellular tetramer staining to demonstrate that a portion of T-cells bound to BMLF1-tetramer could also produce IFNγ following restimulation with IVA-NP85. Tyrosinase peptide served as a non-specific stimulation control. The percentage represents the proportion of the T-cell line binding BMLF1280-tetramer and producing IFNγ. Since the TCR was significantly downregulated upon BMLF1 restimulation, we have also included the total percentage of IFNγ-producing cells in parenthesis, as they would all presumably bind BMLF1-tetramer. (B) Cross-reactive T-cells with specificity for EBV-BMLF1280 and EBV-LMP2329. BMLF1-specific T-cell lines were derived from healthy donor D-002 and were cultured as described in (A). (i) Standard intracellular IFNγ assays are shown, where T-cell lines were restimulated with EBV-LMP2329 or a non-specific peptide, tyrosinase. Positive and negative controls are also provided, BMLF1280 or no restimulation respectively. The percentage of the T-cell line producing IFNγ is shown. (ii) An intracellular IFNγ stain was combined with an extracellular BMLF1280-tetramer stain, where EBV-EBNA 3A peptide served as a non-specific stimulation control. The percentage of the T-cell line binding BMLF1280-tetramer and producing IFNγ is shown. (C) Cross-reactive T-cells with specificity for EBV-BMLF1280 and EBV-BRLF1190 detected ex vivo. CD8 T-cells freshly isolated from (i) IM patient E1232 at day 13 post-presentation and (ii, iii) IM patient E1205 at days 0 and 19 post-presentation were co-stained with tetramers ex vivo, where (IVA)M1-loaded tetramers served as a negative control. (ii,iii)In the presence of EBV-BRLF1190-loaded tetramer, EBV-BMLF1280-specific cells co-stained dimly with BMLF1 tetramer or were blocked from staining with BMLF1 tetramer. . This competition between the tetramers appeared to be similar whether we added the tetramers together or sequentially.

Some donors mounted cross-reactive T-cell responses not only to heterologous virus epitopes but also to other EBV epitopes. EBV-BMLF1280-specific T-cell lines derived from IM donors could contain a population of T-cells which also recognized a latent EBV epitope, LMP329. Figure 1B shows the results for one of these individuals, where 26% of an EBV-BMLF1280–specific line produced IFNγ in response to stimulation with the EBV-LMP2329 peptide (Fig 1Bi). Co-staining studies demonstrated that 9% of the EBV-BMLF1280-tetramer positive population in this line produced IFNγ in response to stimulation with EBV-LMP329 peptide (Fig 1Bii). Control T-cell lines derived from this individual and grown in the absence of the EBV-BMLF1280 peptide or stimulated with IVA-M158 peptide had less than 1% IFNγ-producing CD8 cells following EBV-LMP2329 stimulation, and this small population did not co-stain with BMLF1280-tetramer, further suggesting that the cross-reactive T-cell population responding to LMP2329 was growing in response to the EBV-BMLF1280 peptide.

In freshly isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes (Fig 1C) and in T-cell lines (data not shown) of some IM patients we detected cross-reactive T-cell populations that recognized both EBV-BMLF1280 and EBV-BRLF1190-198, an epitope derived from an immediate-early EBV protein (18). Figure 1C shows ex vivo peripheral blood data demonstrating this cross-reactivity in two patients at the indicated times after presentation with IM. We observed that 0.3% of CD8 T-cells from IM patient E1232 co-stained with both EBV-BMLF1-280 and EBV-BRLF1190-loaded tetramers simultaneously 13 days after presentation with IM (Fig 1Ci). In this patient at this time point there was no evidence for cross-reactivity by tetramer staining between EBV-BMLF1280 and IVA-M158 (Fig 1Ci).

In some of these studies the binding of one tetramer competed with another, suggesting that they were recognizing the same TCR. For instance, in patient E1205, at the time of presentation with IM (day 0), there was not a clear separate population that co-stained with both EBV-BMLF1280- and EBV-BRLF1190-loaded tetramers in freshly isolated CD8 T-cells (Fig 1Cii). However, 1.0% of the BRLF1190-tetramer-staining population also was dimly positive for BMLF1280-tetramer, consistent with this being a crossreactive T cell population. Also, in the presence of EBV-BRLF1190-loaded tetramer, a third (0.9%) of the EBV-BMLF1280-specific cells did not stain with BMLF1 tetramer, as their frequency declined to 0.7% single tetramer positive and 1.0% dim double tetramer positive, in contrast to a frequency of 2.6% in the presence of the control IVA-M158-loaded tetramer (Fig 1Cii). A similar observation was also made a second time in this patient 19 days after presentation with IM; in the presence of EBV-BRLF1190-loaded tetramer, 36% (0.4%) of EBV-BMLF1280-specific cells failed to stain with BMLF1 tetramer, as their frequency declined to 0.7%, in contrast to a frequency of 1.1% in the presence of the control M158-loaded tetramer. Because EBV-BRLF1190- but not IVA-M158-tetramer appears to block the binding of BMLF1280-tetramer, and because the BMLF-1 tetramer staining in the double tetramer positive population is dim compared to the BRLF1 tetramer, there may be cross-reactive T-cells in patient E-1205 that have a higher avidity for the EBV-BRLF1190 epitope than the EBV-BMLF1280 epitope.

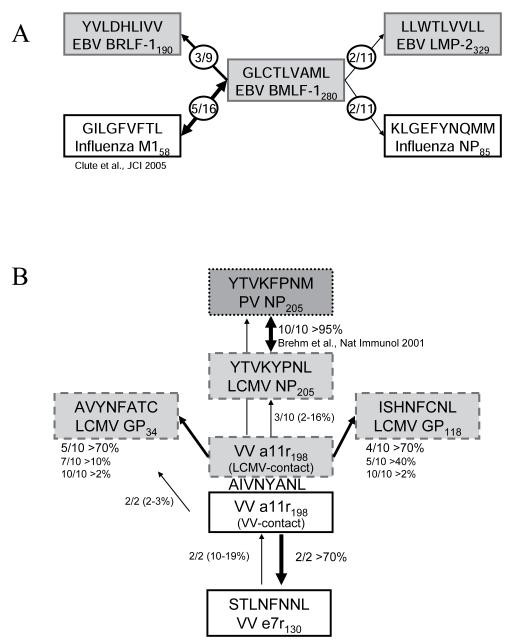

Table 1A shows 0-50% amino acid homology between EBV-BMLF1280 and IVA-M158, IVA-NP85, EBV-LMP2329, and EBV-BRLF-1190. Thus, these cross-reactive patterns could not easily be predicted based on epitope sequence similarity. Also, the networks of cross-reactivity within T-cell populations of different individuals varied, as summarized in the diagram in Figure 2A. For instance, the influenza A-M158 and the EBV-BMLF1280 epitopes are highly conserved targets for HLA-A2-restricted T-cells, yet cross-reactive T-cell responses specific for these two epitopes were only observed in 30% of HLA-A2+ individuals (5). This individual variation in cross-reactive networks is consistent with the concept that the private specificity of each epitope-specific memory T-cell repertoire influences which cross-reactive pattern emerges.

Figure 2. T-cell cross-reactive network between unrelated human or murine viruses focusing on (a) EBV-BMLF1280 and (b) VV-a11r198.

(A) Diagram of cross-reactive CD8 T-cell network in human EBV infection. The EBV-BMLF1280 peptide can activate CD8 T-cell populations specific for 4 different peptides of rather dissimilar sequence derived from 2 different viruses, IAV and EBV. In the diagram of the cross-reactive T-cell responses focused on BMLF1280, the fractions in the figure indicate the number of individuals of the total tested that demonstrated the indicated cross-reactive response. The epitopes in grey or white boxes are EBV and IAV specific, respectively. Cross-reactive responses were detected using both ex vivo and in vitro tetramer and intracellular cytokine staining assays. (B) Diagram of cross-reactive CD8 T-cell network in murine VV infection. The VV-a11r198 peptide can activate CD8 T-cell populations specific for 5 different peptides of similar sequence derived from 3 different virus infections, LCMV, PV and VV. In the diagram of the cross-reactive responses focused on VVa11r198, the fractions in the figure indicate the number of mice of the total tested that demonstrated the indicated cross-reactive response. There are three separate groups, where the light gray box indicates mice that are LCMV-immune (i.e. LCMV-contact), the white color box indicates mice that are VV-immune (i.e. VV-contact) and the dark gray box are mice that are PV-infected. Cross-reactive responses were detected using both ex vivo and in vitro tetramer and intracellular cytokine staining assays.

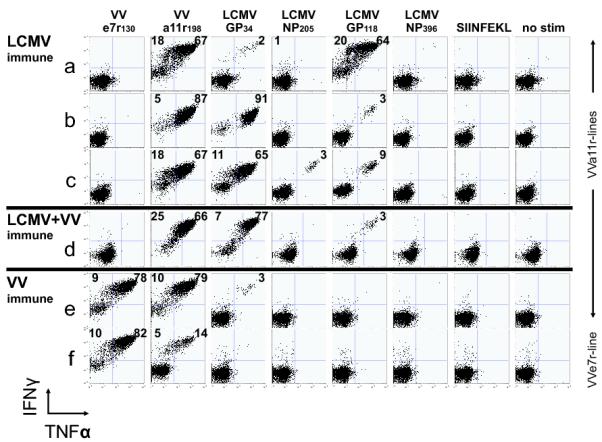

Cross-reactive T-cell networks in mice: one VV epitope can activate three different LCMV-specific memory populations

We questioned whether cross-reactive T-cell networks occurred in the murine model of heterologous virus infection using LCMV-immune mice infected with VV, as the mouse model allows for greater experimental manipulation of the phenomenon. We focused these studies on the H2kb-restricted VV-a11r198 epitope identified by 50% sequence similarity to LCMV-NP205 (Table 1B). T-cells specific to the LCMV-NP205 epitope proliferate in about 50% of LCMV-immune mice challenged with VV (9, 11). The VV-a11r peptide stimulated strong growth of CD8 T-cell lines from LCMV-immune mouse splenocytes which had never previously been exposed to this ligand in vivo (Table 2 and Fig 3). As specificity controls, VV-a11r did not stimulate the outgrowth of T-cells from non-immune mice, and the non-cross-reactive VV epitope e7r130 did not stimulate T-cells from LCMV-immune mice (11). When the VV-a11r-stimulated lines were screened for their reactivity to LCMV epitopes we expected to see cross-reactivity to LCMV-NP205. However, cross-reactivity was generated against three different LCMV H2Kb-restricted epitopes, GP34, GP118 and NP205 (Table 1B) as demonstrated by intracellular cytokine assays (Fig 3), tetramer-staining (Fig 4A,C) and cytotoxicity in 51Cr-release assays (data not shown). For instance, 85-92% of the CD8 cells from three VV-allr198–stimulated T-cell lines originating from 3 different LCMV-immune mice produced IFNγ to their cognate ligand, VV-a11r198, and also to LCMV peptides (Fig 3A,B.C; Table 2). However, each line contained T-cell populations with different patterns of cross-reactivity. In one line 84% of the cells responded to LCMV-GP118 (Fig 3A), in another 91% responded to LCMV GP34 (Fig 3B), and the third had some responsiveness to all three LCMV peptides (Fig 3C). We had previously observed that VV infection of LCMV-immune mice can result in the activation of several LCMV-epitope specific memory populations, depending on the private specificity of the host TCR repertoires (9). However, we did not expect that one VV epitope could activate three (GP34, GP118 and NP205) distinct LCMV-specific memory populations, as these LCMV epitopes do not seem to generate cross-reactive T-cell responses against each other during LCMV infection. For example, we examined many LCMV-NP205 –stimulated lines derived from LCMV-immune mice, and such lines did not demonstrate cross-reactivity with other LCMV epitopes.

Table 2.

Summary of adoptive transfer of cross-reactive (a11r198) and non-cross-reactive (e7r130) VV-specific CD8 T-cell lines that enhanced VV clearance.

| Experiment * | Specificity **,# | VV Titer (log PFU/ml) ± SEM (organ@), day after infection |

% Reduction§ |

P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV/a11r-3 (LCMV+VV: a11r198-spcific T-cell line) n=4 L/a11r-2 (LCMV: a11r198-specific T-cell line) n=4 PBS n=4 |

a11r (98%), GP118 (89%), GP34 (15%), NP205 (0.5%) a11r (75%), GP118 (45%), GP34 (23%)# |

2.56 ± 0.18 (testes) day 4 2.36 ± 0.33 (testes) day 4 3.42 ± 0.26 (testes) day 4 |

86.2 91.3 |

0.008 0.024 |

| LV/a11r-3 (LCMV+VV: a11r198-spcific T-cell line) n=4 L/a11r-2 (LCMV: a11r198-specific T-cell line) n=4 PBS n=4 |

a11r (98%), GP118 (89%), GP34 (15%), NP205 (0.5%) a11r (75%), GP118 (45%), GP34 (23%)# |

3.44 ± 0.25 (fat pads) day 4 3.67 ± 0.10 (fat pads) day 4 4.47 ± 0.20 (fat pads) day 4 |

90.7 84.2 |

0.136 0.049 |

|

| ||||

| L/a11r-4 (LCMV: a11r198-spcific T-cell line) n=4 L/a11r-5 (LCMV: a11r198-specific T-cell line) n=4 PBS n=4 |

a11r (92%), GP34 (91%), GP118 (3%) a11r (85%), GP34 (76%), GP118 (9%), NP205 (3%)** |

2.28 ± 0.38 (testes) day 4 3.07 ± 0.43 (testes) day 4 3.30 ± 0.22 (testes) day 4 |

90.5 41.1 |

0.058 0.214 |

|

| ||||

| L/a11r-6 (LCMV: a11r198-spcific T-cell line) n=2 PBS n=5 |

a11r (72%), GP34 (72%), GP118 (1%), NP205 (1%)# |

3.68 ± 0.04 (testes) day 4 4.74 ± 0.40 (testes) day 4 |

91.3 | 0.012 |

|

| ||||

| VV/e7r-3 (VV: e7r130-specific T-cell line) n=5 L/a11r-7 (LCMV: a11r198-spcific T-cell line) n=5 IV/NP366-2 (Influenza NP366-specific T-cell line) n=3 |

e7r (93%) a11r (96%), GP118 (92%), NP205 (16%), GP34 (1%), NP366 (92%)** |

2.88 ± 0.32 (testes) day 4 4.00 ± 0.39 (testes) day 4 4.49 ± 0.07 (testes) day 4 |

97.6 67.6 |

0.009 0.376 |

|

| ||||

| VV/e7r-1 (VV: e7r130-specific T-cell line) n=5 IV/NP366-1 (Influenza NP366-specific T-cell line) n=4 |

e7r (95%) NP366 (92%)** |

4.21 ± 0.20 (fat pads) day 3 5.34 ± 0.17 (fat pads) day 3 |

92.6 | 0.005 |

|

| ||||

| VV/e7r-2 (VV: e7r130-specific T-cell line) n=5 PBS n=5 |

e7r (92%)** | 3.58 ± 0.18 (fat pads) day 3 5.36 ± 0.14 (fat pads) day 3 |

98.3 | 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| VV/e7r-4 (VV: e7r130-specific T-cell line) n=4 LCMV/NP396-2 (LCMV NP396-specific T-cell line) n=5 PBS n=5 |

e7r (95%) NP396 (94%)** |

4.16 ± 0.21 (testes) day 3 4.93 ± 0.16 (testes) day 3 4.92 ± 0.36 (testes) day 3 |

83.0 (−2.32) |

0.021 0.970 |

VV/VVE7R (VV e7r130), L/VVA11R (a11r198), and LV/VVA11R (a11r198) lines were generated from VV-immune, LCMV-immune or LCMV+VV-immune splenocytes, respectively, and were adoptively transferred into recipient mice and challenged with VV as described in the Materials and Methods; Specificity of each CD8 T-cell line was determined in

ICS assays or

tetramer staining;

Fat pads or testes were harvested 3-4 days post VV infection and analyzed for VV titers by plaque assays;

Percentage reduction of VV load in the experimental groups as compared to the control group.

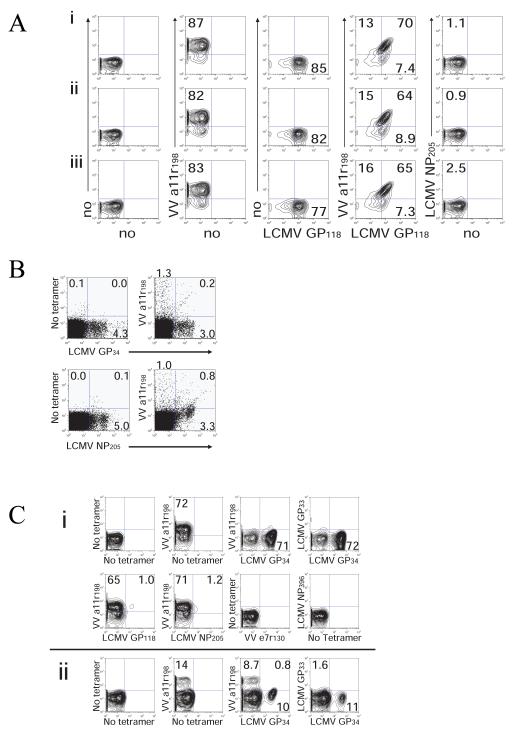

Figure 3. Cross-reactive T-cell responses in mice. Pattern of cross-reactivity varies between individual mice and prior infection history.

VV-a11r-specific T-cell lines were generated from LCMV-immune (A-C), LCMV-immune+VV-immune (D), or VV-immune (E-e) C57BL/6 mice. VV-e7r-specific T-cell lines were generated from VV-immune mice (F-f). Indicated peptides were used for stimulation in ICS assays. Results are representative of 2 to 10 cell lines/group.

Figure 4.

(A) Pattern of cross-reactivity is similar between 3 different cultures from one individual mouse. Three individual VV-a11r198 cell lines (i, ii, iii) were generated from one LCMV-immune mouse and were stained with either one or two tetramers simultaneously. (B) Presence of cross-reactive CD8 T-cells ex vivo during VV infection (day 6) of LCMV-immune mice. Double-tetramer staining demonstrates the presence of cross-reactive CD8 T-cells that recognize both VV-a11r198 and LCMV-GP34 as well as VV-a11r198 and LCMV-NP205 (gated on CD8 cells). (C) Double tetramer staining of two a11r198-specific T-cell lines generated from two different LCMV-immune mice (i) The majority of this 3 week culture of an a11r-specific T-cell line bound either LCMV-GP34 or VV-a11r198-tetramers when stained separately. Co-staining with both tetramers resulted in blocking of the LCMV-GP34 tetramer blocking binding of the VVa11r tetramer. (ii) In a second VV-a11r-specific T-cell line, after a short-term 10 day culture, co-staining experiments with LCMV-GP34 tetramer blocked about 5% of the VV-a11r tetramer binding (gated on CD8).

Although the cross-reactive epitope-specificity of the CD8 T-cell populations varied among VV-a11r198-specific lines derived from different individual LCMV-immune mice (Fig 3A-C, Table 2), they were highly reproducible among separate lines derived from the same LCMV-immune mouse. Figure 4Ai-iii shows that each of three separate lines had a similar pattern of cross-reactivity when co-staining with VV-a11r198- and LCMV-GP118-tetramers. In contrast, in a total of 10 lines, five VV-a11r198-specific CD8 T-cell lines derived from different mice showed dominant cross-reactivity with LCMV-GP118, corresponding to more than 84% of each line responding to both peptides (Fig 3A, 4A, Table 2). However, the other five T-cell lines showed strong cross-reactivity with LCMV-GP34 (Fig 3B-C, Table 2), and three of these were also moderately reactive with LCMV-NP205 (Fig 3C, Table 2). LCMV-NP205 and PV-NP205 share 6 of 8 amino acids at sites important for TCR interaction (Table 1B), and LCMV-NP205-specific CD8 T-cells cross-react with PV-NP205 (12). As expected, all four of four cell lines that responded to LCMV-NP205 also responded to PV-NP205 (data not shown).

CD8 T-cells cross-reactive with VV-a11r198 and LCMV-GP34 or -NP205 were also directly detected in cells freshly isolated from LCMV-immune mice challenged with VV (Fig 4B). CD8 frequencies detected by tetramer staining directly ex vivo for VV-specific and cross-reactive responses were lower than in cell lines, but still detectable, indicating the normal presence of cross-reactive cells in vivo. This is analogous to the generally low frequencies observed in vivo in most human virus-specific responses (Fig 1C). Cell lines, however, provide a useful technique both in humans and mice for amplifying and characterizing these cross-reactive responses.

Co-staining with two tetramers to define cross-reactive populations was not always a useful technique to demonstrate cross-reactive responses (Fig 4C). For instance, in some cases the majority of the T-cells in lines from LCMV-immune mice stimulated with VV-a11r stained with either VV-a11r198- (70%) or LCMV-GP34-tetramers (72%), indicating that many of the T-cells were cross-reactive. However, when co-staining with both tetramers simultaneously or even sequentially in this same culture, the LCMV-GP34-tetramer was noted to completely block the VV-a11r198-tetramer binding, which declined from 70% to 0% (Fig 4Ci). These results suggest that in this mouse these VV-a11r-specific cells are higher avidity to the original ligand, LCMV-GP34, which they first saw in vivo during the LCMV infection, than to the stimulating VV peptide. In this same line the LCMV-NP205 tetramer detected a low frequency of cross-reactive cells with VV-a11r but did not block the binding of the VV-a11r tetramer. In other VV-a11r-specific T-cell lines generated from LCMV-immune mice there was partial blocking of VV-a11r tetramer binding. For instance, co-staining with both tetramers simultaneously showed that the LCMV-GP34 tetramer blocked about 5% of the VV-a11r tetramer binding (Fig 3Cii). This competition between tetramers for TCR binding suggests that, in these two particular cell lines, the cross-reactive populations may bind the epitope (LCMV-GP34), specific for the first virus encountered with higher avidity than the cross-reactive epitope (VV-a11r198) which reactivated some part of this memory population.

History of virus infection influences pattern of VV-a11r198 cross-reactivity and reveals that VV intraviral cross-reactive T-cell responses only become apparent in VV-immune but not in LCMV+VV-immune mice

The private specificity of epitope-specific memory T-cell repertoire development is proposed to be influenced by the stochastic processes of T-cell selection in the thymus and by the random encounters of T-cells with their ligands in the periphery (29). These processes also influence the pattern of VV-a11r-specific cross-reactive responses that predominate in each individual LCMV-immune host upon VV infection (9). The specific sequential order of virus infections is a third factor which could influence the pattern of VV-a11r198-specific cross-reactive responses. For example, cross-reactive T-cell responses to the three LCMV epitopes were very low or absent in VV-a11r-specific lines generated from splenocytes of VV-immune mice (Fig 3E). This indicates that the majority of VV a11r-specific T-cells generated during acute VV infection of naive mice is not cross-reactive with LCMV epitopes and suggests that acute VV infection generates a different T-cell repertoire in naïve mice compared to LCMV-immune mice. Having an enhanced precursor frequency of these cross-reactive clones in the LCMV-specific memory pool was apparently necessary for their amplification and detection during acute VV infection.

The VV-e7r130 epitope was not cross-reactive with LCMV, and VV-e7r-specific T-cell lines could not be established by stimulating LCMV-immune splenocytes with VV-e7r130. Interestingly, some T-cells in a11r-specific lines generated from VV-immune splenocytes were cross-reactive with VV-e7r130 (Fig 3E). Eighty-eight percent of a cell line cultured with VV-a11r198 peptide also responded to the VV-e7r130 peptide (Fig 3E). This cross-reactivity was not completely reciprocal, as only 19% of a cell line derived from the same VV-immune mouse but cultured with VV-e7r130 peptide also responded to the VV-a11r198 peptide (Fig 3F). As expected, the VV-e7r130 line generated from this VV-immune mouse did not react with any LCMV epitopes (Fig 3F). By comparison, two different VV-a11r-stimulated lines derived from the splenocytes of mice that were immune to both LCMV and VV, given sequentially in that order, did not cross-react with VV-e7r130 but did cross-react with the three LCMV epitopes, GP34, GP118 and NP205 (Fig 3D & Table 2 -LV/a11r-3 line). These data suggest that the VV-a11r198 memory repertoire resulting from the activation of cross-reactive LCMV-specific memory cells during acute VV infection of LCMV-immune mice did not include T-cells cross-reactive with the VV-e7r130 epitope. Thus, T-cell cross-reactivity between VV and LCMV is highly plastic, where a11r-specific T populations contain subsets of cells with the potential to cross-react with 5 different epitopes derived from 3 viruses (LCMV, PV and VV) and where the cross-reactive network that emerges in a given individual is influenced by the history of sequential virus infections, as diagrammed in Figure 2b.

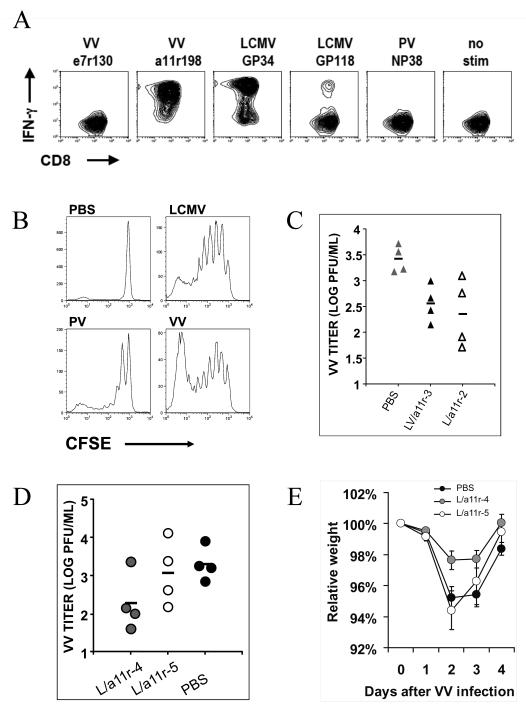

Cross-reactive CD8 T-cell lines reduce VV virus titer in vivo

Immunity to LCMV is known to mediate partial protection against VV infection, and adoptive transfer studies using splenocytes from LCMV-immune mice demonstrated that T-cells were mediating this effect (8). Despite a strong correlation between the activation of cross-reactive memory CD8 T-cells and protective heterologous immunity (7, 8), direct evidence that cross-reactive CD8 T-cells proliferate in vivo in response to the heterologous virus and mediate protective heterologous immunity has been lacking. We therefore tested cross-reactive cell lines in vivo for their proliferation and manifestation of protective heterologous immunity. VV-a11r-specific lines generated from LCMV-immune splenocytes (Fig 5) were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred i.p. into naïve congenic mice, which were then infected with VV. These VV-a11r-specific CD8 T-cells proliferated in response to both LCMV and VV infection but not to PV infection in vivo (Fig 5B). Next, we tested a11r-specific lines generated from different mice for their ability to reduce VV load. Regardless of whether they were generated from an LCMV-immune mouse (L/a11r-2; L/a11r-4; L/a11r-6) or a mouse that had been infected with VV (LV/a11r-3), four of six VV-a11r-specific lines with high levels of cross-reactivity to LCMV-GP118 or -GP34 all significantly decreased VV titers by an average of 89±1% upon adoptive transfer into naïve hosts (Table 2, Fig 5C,D). This level of protection was consistent, as demonstrated by using the same cell lines (L/a11r-2; L/a11r-3) twice, in two separate experiments (Table 2). Furthermore, these four cross-reactive VV-a11r-specific cell lines generated from LCMV-immune mice were found to be as effective as four putatively non-cross-reactive VV-e7r-specific cell lines generated from VV-immune mice (Table 2).

Figure 5. Cross-reactive a11r-specific CD8 T-cells proliferate in vivo after LCMV or VV infection and reduce VV load.

(A) This is a representative a11r-specific CD8 T cell line (L/a11r-4) derived from LCMV-immune splenocytes; it was predominantly cross-reactive with LCMV-GP34 but also recognized GP118 in an IFNγ ICS assay. (B) Cross-reactive a11r-specific line proliferates in response to LCMV and VV but not to PV-infected or PBS-treated controls, as assessed by loss of CFSE label by day 3 post the simultaneous adoptive transfer and infection of congenic LY5.1 mice. (C) Adoptive transfer of cross-reactive a11r-specific CD8 T-cell lines derived from an LCMV+VV-immune mouse (▲LV/a11r-3) or an LCMV-immune mouse (△L/a11r-2) led to a significant VV reduction compared to PBS controls ( ). VV titers in the testes were assayed on day 4 post-infection (LV/a11r-3 vs. PBS: p<0.01; L/a11r-2 vs. PBS: p<0.05). (D) Differential effect on VV titers upon the use of different cross-reactive a11r-specific CD8 T-cell lines, L/a11r-4 and L/a11r-5. There was a greater reduction of VV titers in testes day 4 post-infection in mice injected with L/a11r-4 (

). VV titers in the testes were assayed on day 4 post-infection (LV/a11r-3 vs. PBS: p<0.01; L/a11r-2 vs. PBS: p<0.05). (D) Differential effect on VV titers upon the use of different cross-reactive a11r-specific CD8 T-cell lines, L/a11r-4 and L/a11r-5. There was a greater reduction of VV titers in testes day 4 post-infection in mice injected with L/a11r-4 ( ) compared to L/a11r-5 (엯)(p<0.08, n=4), or PBS (●)(p<0.08, n=4). (E) Time course of weight loss after VV infection. Adoptive transfer of the T-cell line L/a11r-4 resulted in a 50% inhibition of weight loss (day 2: 2.4%±0.6% vs. 4.8%±0.7% weight loss, n=4, p=0.06; day 3: 2.3%±0.5% vs. 4.5%±0.7% weight loss, n=4, p=0.08) post VV-infection, while T-cell line L/a11r-5 did not affect weight loss when compared to the control, PBS injected, mice (p>0.3).

) compared to L/a11r-5 (엯)(p<0.08, n=4), or PBS (●)(p<0.08, n=4). (E) Time course of weight loss after VV infection. Adoptive transfer of the T-cell line L/a11r-4 resulted in a 50% inhibition of weight loss (day 2: 2.4%±0.6% vs. 4.8%±0.7% weight loss, n=4, p=0.06; day 3: 2.3%±0.5% vs. 4.5%±0.7% weight loss, n=4, p=0.08) post VV-infection, while T-cell line L/a11r-5 did not affect weight loss when compared to the control, PBS injected, mice (p>0.3).

The qualitative characteristics of a cross-reactive response may determine its effectiveness against VV

These well characterized cross-reactive cell lines were useful for asking whether there may be qualitative differences in cross-reactive responses. For instance, two of the six VV-a11r-specific CD8 T-cell lines, L/a11r-5 and L/a11r-7, generated from different individual LCMV-immune mice were poorly efficient at mediating protective immunity (Fig 5D; Table 2). Adoptive transfer of the line L/a11r-5 resulted in no protection from weight loss and only a 41% reduction in VV titers when compared to controls. This is in contrast to adoptive transfer of a protective line such as L/a11r-4, which resulted in inhibition of weight loss (Fig 5E) and a significant 90% reduction in VV titers at day 4 of VV infection (Fig 5D).

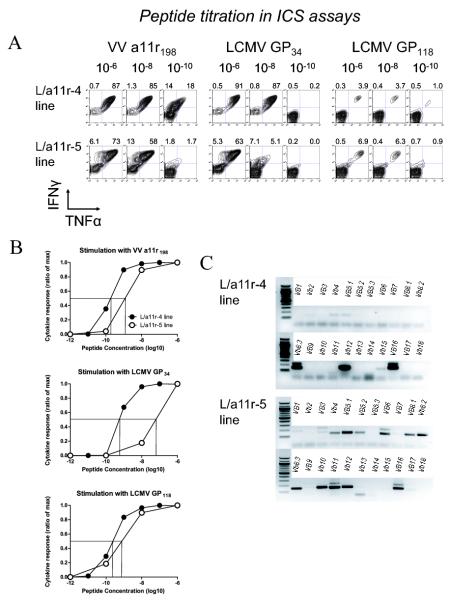

Variations in the degree of protective immunity against VV mediated by different T-cell lines suggest that cross-reactive responses can be qualitatively different. We characterized the cross-reactive profile of two cell lines by 1) estimating TCR avidity to VV a11r198 and to the alternate LCMV epitopes using peptide titration in an intracellular cytokine assay, and 2) assessing differences in TCR repertoire (Fig 6). The two lines differed in their cross-reactive pattern, as the protective L/a11r-4 line was dominated by a VV-a11r198-specific CD8 T-cell population that predominantly recognized LCMV-GP34 (91%), with 3% of the population recognizing GP118, while the non-protective L/a11r-5 had broader cross-reactive specificity in that it recognized LCMV GP34 (76%), GP118 (9%), and NP205 (3%) (Table 2). The cytokine profile of these two lines in response to VV a11r198 also differed. The protective L/a11r-4 line produced both TNFα and IFNγ (85%) equally in response to the VV-a11r198 peptide, whereas only 58% of the non-protective L/a11r-5 line produced both cytokines in response to VV-a11r198 peptide at 10−8 M, and a subset (13%) of cells produced only IFNγ and not TNFα (Fig 6A).

Figure 6. Two a11r-specific cross-reactive CD8 T-cell lines show different patterns of avidity to cross-reactive epitopes and different TCR repertoires.

(A,B) Titration of peptide concentrations in ICS assays using a11r-specific lines L/a11r-4 and L/a11r-5. The indicated concentrations of VV-a11r198, LCMV-GP34, -GP118, and -NP205 peptides were used in a 4 hour ICS assay to stimulate the production of IFNγ and TNFα by the a11r-specific T-cell lines L/a11r-4 or L/a11r-5, which were generated from two different LCMV-immune mice. The percentage of IFNg+ or IFNg+ TNFa+ cells of total CD8+ is shown above each plot. The numbers above the upper quadrants represent the percent cytokine production (gated on CD8). The percentage of maximum cytokine response to each peptide concentration is graphed in B. (C) Private specificity in TCR Vβ repertoire: TCR Vβ mRNA expression of the L/a11r-4 and L/a11r-5 T-cell lines demonstrates different a11r-specific Vβ repertoires in lines derived from two different LCMV-immune mice.

These cross-reactive T-cell populations also varied in their estimated avidity for the cross-reactive antigen when tested by peptide titration in ICS assays, although both were in a range reported for many antigen-specific clones and therefore thought to be physiologically relevant (30). For instance, the avidity for VV-a11r198 was at least 10-fold higher in the protective line L/a11r-4 (E:C50 of 1010), with 32% of the line still responding to the peptide at a 10−10 M, when compared to the non-protective L/a11r-5 (E:C50 of 109) line that barely responded at this same concentration (Fig 6A&B). The non-protective line L/a11r-5 (E:C50 of 5×109) also had a greater than 100-fold lower avidity for the LCMV-GP34 epitope when compared to the protective line L/a11r-4 (E:C50 of 107) (Fig 6A&B). The unique cross-reactive patterns and differences in TCR avidity for the same epitope suggested that their clonal composition would be different. Analysis of TCR Vβ expression in these lines using a PCR-based technique confirmed that these cross-reactive T-cells were not single clones but contained multiple clonotypes with major differences in repertoire. The protective L/a11r-4 line predominantly used the Vβ8.3, Vβ12 and Vβ16 families, whereas the non-protective L/a11r-5 line had much broader Vβ usage that included the Vβ5.1, 6, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 10, 11, 12 and 16 families (Fig 6C). We also used Vβ mAbs for a more quantitative assessment of the TCR repertoire although we are not able to stain for Vβ16 as there is no mAb available. The protective line L/a11r4 revealed a narrowrepertoire with Vβ12 representing 95% of the response and Vβ8.3, 2%. The less-protective line L/a11r5 was broader with Vβ11, Vβ8.1/8.2, and Vβ8.3 representing 63%, 15% and 4% of the responses, respectively. We also did SMART Race PCR to assess the clonoytpes present in each culture, and these results supported the same finding that the protective line had a skewed repertoire dominated by one Vβ12 clonotype, while the less protective line had a broader Vβ usage (See supplemental Table 1). These results demonstrated that these cross-reactive CD8 T-cell lines have qualitative differences that might influence their effectiveness at clearing VV infection.

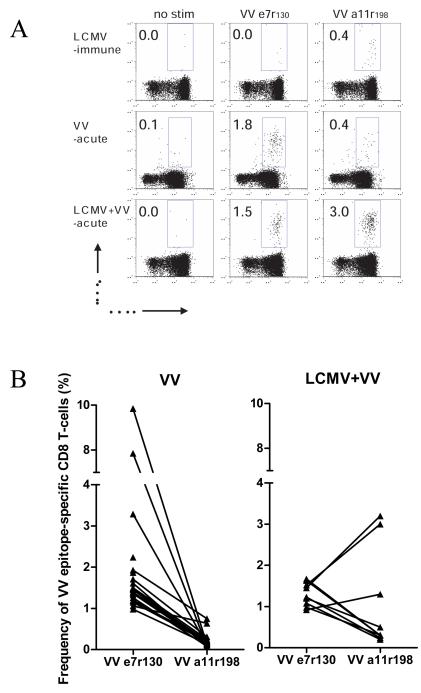

Cross-reactivity alters the immunodominance hierarchy during VV infection

The advantage of using a murine model is the ability to manipulate the sequence of virus infections in vivo and track the effects cross-reactive responses have on both immunodominance hierarchies and protection. For instance, the hierarchy of VV-epitope specific CD8 T-cell responses typically observed during VV infection of naïve mice was altered in the presence of cross-reactive LCMV memory T-cell responses. All naïve mice infected with VV generated a VV-e7r130 response higher than that to VV-a11r198, and all examined LCMV-immune mice generated a weak response to VV-a11r198 but no response to VVe7r130. Figure 7A shows a representative experiment with an LCMV-immune mouse that had a change in immunodominance as reflected by an enhanced response to the VV-a11r198 epitope upon VV infection compared to a naïve mouse. A similar change in the VV epitope immunodominance hierarchy was observed in 33% (3/9) of the LCMV-immune mice examined in this experiment (Fig 7B). In 8 of 21 mice examined overall in several experiments, there was an enhanced expansion of VV-a11r198-specific cells. Thus, just as T-cell lines derived from each mouse showed different patterns of cross-reactivity, individual mice showed a different pattern of cross-reactive proliferation in vivo. This altered the VV epitope immunodominance hierarchy and was apparently influenced by the private cross-reactive repertoire of the host.

Figure 7. Change of immune hierarchy in LCMV-immune mice infected with VV.

(A). Lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of naïve mice (VV acute) or the same LCMV-immune mice before (LCMV-immune) or 6 days after VV infection (LCMV+VV acute). The lymphocytes were stimulated with the indicated peptide in a 6 hr intracellular IFNg assay. We show a representative example of how a typically subdominant VV-a11r198 response during acute VV infection becomes immunodominant when the host has been previously exposed to LCMV. Percentage of CD44hi CD8 T-cells responding to the indicated peptide is shown. (B) A summary of the data derived from ICS assays shows that a shift in VV epitope immunodominance hierarchy among LCMV+VV mice occurred in 3 out of 9 mice analyzed (30%). The line drawn between the epitopes indicates the results from the same mouse.

DISCUSSION

Cross-reactive CD8 T-cell responses have previously been reported during viral infection, but their commonality and importance has not been appreciated (3-5, 12). These studies here demonstrate that it is highly likely that T-cell cross-reactivity may be the rule rather than the exception. We demonstrate, in both humans and mice, that cross-reactive T cell responses are so common that we can track populations of cells within complex well-defined networks where subsets of T cell populations reactive with one epitope cross-reacted with either of several other epitopes encoded by the same or heterologous viruses (Fig 2A&B). Our data suggest that the specific antigens that are co-recognized depend on a number of factors that include 1) the inherent structural characteristics of the epitopes, 2) the private specificity of the individual’s naïve TCR repertoire, 3) the sequential order of infections, and 4) the resulting alterations in the private specificity of memory TCR repertoire with each new infection. Using a mouse model we were able to study the direct impact of these cross-reactive responses in vivo. Immunodominance hierarchies could be altered in the presence of cross-reactive T-cell responses (Fig 7), and cross-reactive responses could impact disease outcome by enhancing viral clearance (Fig 5, Table 2). Our data also suggest that the qualitative characteristics of the cross-reactive T-cell responses may relate to their effectiveness at providing protective immunity to future infections. This needs further study and could lead to a better understanding of what qualitative characteristics of T-cell cross-reactivity (i.e. avidity, specific Vβ usage and functional response to the ligands), maximizes the effectiveness of cell-mediated immunity, while minimizing immunopathology. This information would be particularly useful in designing vaccines. Of interest is that a large trial of a T-cell-based vaccine against HIV used an adenovirus vector, and the individuals with prior immunity to adenovirus developed an increased incidence of HIV infection (31, 32). It is possible that heterologous immunity played some role in mediating this adverse outcome.

Here we demonstrated human cross-reactive T cell responses where subsets of T cells specific to one EBV epitope, BMLF1280, could cross-react with up to two influenza A (M158 and NP85) and two other intraviral EBV epitopes (BRLF-1190 and LMP2329) (Fig 2A). In mice, we showed that subsets of T cell populations specific to the typically subdominant VV epitope, a11r198, had the potential to cross-react with 5 different immunogenic epitopes, LCMV-GP118, -GP34, -NP205, PV-NP205, and VV-e7r130 derived from 3 different viruses, LCMV, PV and VV (Fig 2B). We have no evidence that a single VV-a11r-specific CD8 T-cell can recognize all 5 epitopes, as most of our data suggest that a single T-cell may recognize 2 epitopes or 3 in the case where two of the epitopes are highly homologous like PV-NP205 and LCMV-NP205. Structural similarity does play a role in cross-reactive T-cell responses. Although all 5 of these epitopes have 50% or less sequence similarity to VV a11r198, they do share amino acids at positions 4, 6, and 7 (Table 1). Structural studies of 3 different H-2Kb/peptide interactions with TCR have shown that side chains of amino acids at positions 4, 6, and 7 of the peptide are crucial for interaction with the TCR (33). These studies, plus the knowledge that an individual TCR can tolerate certain amino acid substitutions in the peptide sequence and still become activated (34), help explain why a11r-specific CD8 T-cells could potentially cross-react with 5 alternate epitopes. The fact that TCRs are reportedly able to undergo significant conformational changes upon binding to antigen gives them the capability to interact with diverse structures and enhances the occurrence of cross-reactive responses (35). Also a recent report systematically examined many known cross-reactive T-cell responses, including all of our reported epitopes, and suggested that sequence similarity based on biochemically similar and not necessarily identical amino acids directly correlated with an increased likelihood of cross-reactivity (36). This may help explain why epitopes with much less sequence similarity, such as EBV-BMLF1280 and influenza A-M158 or EBV-BRLF1190 (Table 1A), can also stimulate cross-reactive T-cell responses.

The ability to track and predict cross-reactive T-cell responses could be useful in designing vaccines, in determining the order and combination of vaccines in children, and in predicting the outcome of disease after infection in any particular individual. However, in order to achieve this there are other contributing factors that are identified in this study that increase the complexity and difficulty in predicting cross-reactive responses. This includes the diversity (37) and the private specificity of antigen-specific TCR repertoires (9, 23, 29, 38-40) as well as the resulting qualitative differences in cross-reactive responses depending on the cross-reactive clone. Individual LCMV-immune mice mounted complicated VV-a11r198 responses that cross-reacted with LCMV epitopes, GP34, GP118 and NP205 to varying extents (Fig 3A-C). Isolating and identifying highly reproducible dominant cross-reactive responses thus far has not been common, although not many studies have directly focused on identifying cross-reactive responses as was done in the present study in the context of sequential heterologous virus infections. Awareness of the variability in the sequence of virus infections and the private specificity of an individual’s TCR repertoire, which plays a major role in determining cross-reactive patterns, can assist investigators in tracking dominant cross-reactive T-cell responses, as we have done in both mice and humans (Fig 2A&B). It should be noted that functionally relevant cross-reactive responses are more easily detected within memory T-cell populations compared to naïve, as memory T-cells are present at a much higher frequency and exist in an enhanced activation state (41-43). Thus, for all these reasons trying to study T cell cross-reactivity using the conventional technique of deriving high avidity T cell clones which are highly selected with repeated stimulation with one antigen may underestimate the prevalence of cross-reactive T cell responses.

In order to best control for variables caused by private specificity patterns and the fact that we may be only observing a subset of potential cross-reactivity patterns, we decided that well characterized cell lines were the best approach to directly test if cross-reactive CD8 T-cell responses could mediate protective immunity. When we transferred LCMV-immune splenocytes from one mouse into three naïve congenic hosts all three mice expand the same LCMV-epitope specific population upon VV infection, but patterns of expansion differ among donors. Consistent with the in vivo adoptive transfer model, cultures from 10 different mice showed different patterns of cross-reactivity while three cultures from the same mouse were similar (9). Thus, by transferring the expanded well-characterized cross-reactive T-cell lines into a host we can monitor their proliferation and influence on virus infection in vivo. Here we directly demonstrate for the first time that cross-reactive T-cell lines can enhance viral clearance (Fig 5, Table 2).

In general, the efficiency of viral clearance by activated T-cells is at least partially dependent on the avidity of the TCR interaction with its ligand. Studies with altered peptide ligands (APL), an artificial model of cross-reactivity, show that high- and low-potency ligands differ in the length of time the TCR interacts with MHC/ligand, i.e. TCR avidity, and that this can modify the functional potential of individual clones (44, 45). Thus, a low avidity TCR interaction with an alternate ligand may induce different cytokines or a different hierarchy of cytokine production that results in less efficient killing and proliferation than T-cells interacting with their original ligand with presumably higher avidity. This may help explain why a cross-reactive T-cell line (L/a11r-5) that interacted with a VV epitope with lower avidity had an altered cytokine profile and did not protect as well against a heterologous VV challenge (Fig 5, 6) or why heterologous immunity may not be as effective at mediating protective immunity as homologous immunity.

It is highly likely that just the existence of a cross-reactive T-cell response does not lead to protective effects. In some cases, cross-reactive responses may lead to immunopathology, as shown in murine models (7, 8), and also observed in human infections (4). Many factors, such as TCR avidity and the functional response (e.g. cytokine production or cytotoxic capability) to alternate epitopes, influence the effectiveness of a cross-reactive response. This is a subject about which we still have a great deal to learn and suggest that future studies should focus on identifying the characteristics of cross-reactive T-cells which lead to better protective immunity.

T-cell responses can sometimes be detrimental to the host and mediate significant immunopathology. LCMV is a classic example where the same T-cells responsible for viral clearance mediate a severe leptomeningitis if the virus is replicating in the brain (46). Whether disease outcome is subclinical or severely symptomatic with associated immunopathology (e.g. infectious mononucleosis (5), VV-induced erythema nodosum and bronchiolitis obliterans (7, 8), or associated autoimmune conditions (47), seems dependent on the fine balance between the number of memory T-cells recruited to sites of viral infection, their effectiveness at clearing virus, and the length of time these T-cells are amplifying the inflammatory response. A particular cross-reactive response may change the avidity with which a foreign ligand is recognized and, therefore, the functional consequences of interaction with that ligand, such as changing the cytokine profile (5, 44). Our studies highlight the variations in immune responsiveness that can occur not only because of a unique history of previous infections but also because of a host’s unique immune repertoire, and the complex plasticity of T-cell cross-reactivity described here illustrates the pervasiveness of this phenomenon and our ability to trace these patterns. Ultimately, our ability to track and characterize these flexible cross-reactive networks within and between individuals may help us to design useful vaccine strategies and perhaps even predict and prevent immunopathology during viral infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank K.A. Daniels and F. Jeffe for their technical assistance, and Katherine Luzuriaga, John Sullivan, F.A. Ennis, H. Wedemeyer, and E. Szomolanyi-Tsuda for helpful discussion. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official view of the NIH.

This study was supported by NIH grants AI-46578 (RMW) (LKS), AI-49320 (LKS), AI-42845, DR-32520, an immunology training grant 5 T32 AI-07349-16 and DFG fellowship CO 310/1-1 and CO310/2-1 (MC), Germany.

Abbreviations

- VV

vaccinia virus

- LCMV

lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- PV

Pichinde virus

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- ICS

intracellular cytokine staining

- CFSE

5- (and 6-)carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- IFN

interferon

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- EBV

Epstein Barr virus

- IM

infectious mononucleosis

- IAV

influenza A

REFERENCES

- 1.Welsh RM, Selin LK. No one is naive: the significance of heterologous T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:417–426. doi: 10.1038/nri820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selin LK, Cornberg M, Brehm MA, Kim SK, Calcagno C, Ghersi D, Puzone R, Celada F, Welsh RM. CD8 memory T cells: cross-reactivity and heterologous immunity. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh RM, Selin LK, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E. Immunological memory to viral infections. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:711–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urbani S, Amadei B, Fisicaro P, Pilli M, Missale G, Bertoletti A, Ferrari C. Heterologous T cell immunity in severe hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med. 2005;201:675–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clute SC, Watkin LB, Cornberg M, Naumov YN, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Cross-reactive influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells contribute to lymphoproliferation in Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3602–3612. doi: 10.1172/JCI25078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehermann B, Shin EC. Private aspects of heterologous immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:667–670. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HD, Fraire AE, Joris I, Brehm MA, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Memory CD8+ T cells in heterologous antiviral immunity and immunopathology in the lung. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1067–1076. doi: 10.1038/ni727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selin LK, Varga SM, Wong IC, Welsh RM. Protective heterologous antiviral immunity and enhanced immunopathogenesis mediated by memory T cell populations. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1705–1715. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SK, Cornberg M, Wang XZ, Chen HD, Selin LK, Welsh RM. Private specificities of CD8 T cell responses control patterns of heterologous immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:523–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB. Amino acid homology between the encephalitogenic site of myelin basic protein and virus: mechanism for autoimmunity. Science. 1985;230:1043–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.2414848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornberg M, Sheridan BS, Saccoccio FM, Brehm MA, Selin LK. Protection against vaccinia virus challenge by CD8 memory T cells resolved by molecular mimicry. J Virol. 2007;81:934–944. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01280-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brehm MA, Pinto AK, Daniels KA, Schneck JP, Welsh RM, Selin LK. T cell immunodominance and maintenance of memory regulated by unexpectedly cross-reactive pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:627–634. doi: 10.1038/ni806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wedemeyer H, Mizukoshi E, Davis AR, Bennink JR, Rehermann B. Cross-reactivity between hepatitis C virus and Influenza A virus determinant-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Virol. 2001;75:11392–11400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11392-11400.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy PT, Urbani S, Moses RA, Amadei B, Fisicaro P, Lloyd J, Maini MK, Dusheiko G, Ferrari C, Bertoletti A. The influence of T cell cross-reactivity on HCV-peptide specific human T cell response. Hepatology. 2006;43:602–611. doi: 10.1002/hep.21081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilges K, Hohn H, Pilch H, Neukirch C, Freitag K, Talbot PJ, Maeurer MJ. Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 peptide-directed CD8+ T cells from patients with cervical cancer are cross-reactive with the coronavirus NS2 protein. J Virol. 2003;77:5464–5474. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5464-5474.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selin LK, Nahill SR, Welsh RM. Cross-reactivities in memory cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition of heterologous viruses. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1933–1943. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen HD, Fraire AE, Joris I, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Specific history of heterologous virus infections determines anti-viral immunity and immunopathology in the lung. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1341–1355. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63493-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Most RG, Murali-Krishna K, Whitton JL, Oseroff C, Alexander J, Southwood S, Sidney J, Chesnut RW, Sette A, Ahmed R. Identification of Db- and Kb-restricted subdominant cytotoxic T-cell responses in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice. Virology. 1998;240:158–167. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Most RG, Murali-Krishna K, Lanier JG, Wherry EJ, Puglielli MT, Blattman JN, Sette A, Ahmed R. Changing immunodominance patterns in antiviral CD8 T-cell responses after loss of epitope presentation or chronic antigenic stimulation. Virology. 2003;315:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitton JL, Gebhard JR, Lewicki H, Tishon A, Oldstone MB. Molecular definition of a major cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope in the glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol. 1988;62:687–695. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.687-695.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudrisier D, Oldstone MB, Gairin JE. The signal sequence of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus contains an immunodominant cytotoxic T cell epitope that is restricted by both H-2D(b) and H-2K(b) molecules. Virology. 1997;234:62–73. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townsend AR, Rothbard J, Gotch FM, Bahadur G, Wraith D, McMichael AJ. The epitopes of influenza nucleoprotein recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes can be defined with short synthetic peptides. Cell. 1986;44:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornberg M, Chen AT, Wilkinson LA, Brehm MA, Kim SK, Calcagno C, Ghersi D, Puzone R, Celada F, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Narrowed TCR repertoire and viral escape as a consequence of heterologous immunity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1443–1456. doi: 10.1172/JCI27804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalina MD, Sullivan JL, Bak KR, Luzuriaga K. Differential evolution and stability of epitope-specific CD8(+) T cell responses in EBV infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:4450–4457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steven NM, Annels NE, Kumar A, Leese AM, Kurilla MG, Rickinson AB. Immediate early and early lytic cycle proteins are frequent targets of the Epstein-Barr virus-induced cytotoxic T cell response. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1605–1617. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gotch F, Rothbard J, Howland K, Townsend A, McMichael A. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize a fragment of influenza virus matrix protein in association with HLA-A2. Nature. 1987;326:881–882. doi: 10.1038/326881a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robbins PA, Lettice LA, Rota P, Santos-Aguado J, Rothbard J, McMichael AJ, Strominger JL. Comparison between two peptide epitopes presented to cytotoxic T lymphocytes by HLA-A2. Evidence for discrete locations within HLA-A2. J Immunol. 1989;143:4098–4103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SP, Thomas WA, Murray RJ, Khanim F, Kaur S, Young LS, Rowe M, Kurilla M, Rickinson AB. HLA A2.1-restricted cytotoxic T cells recognizing a range of Epstein-Barr virus isolates through a defined epitope in latent membrane protein LMP2. J Virol. 1993;67:7428–7435. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7428-7435.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh RM, Kim SK, Cornberg M, Clute SC, Selin LK, Naumov YN. The privacy of T cell memory to viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:117–153. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis MM, Boniface JJ, Reich Z, Lyons D, Hampl J, Arden B, Chien Y. Ligand recognition by alpha beta T cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:523–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. AIDS research. Did Merck’s failed HIV vaccine cause harm? Science. 2007;318:1048–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.318.5853.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ledford H. HIV vaccine may raise risk. Nature. 2007;450:325. doi: 10.1038/450325a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudolph MG, Wilson IA. The specificity of TCR/pMHC interaction. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:52–65. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gotch F, McMichael A, Rothbard J. Recognition of influenza A matrix protein by HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Use of analogues to orientate the matrix peptide in the HLA-A2 binding site. J Exp Med. 1988;168:2045–2057. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.6.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willcox BE, Gao GF, Wyer JR, Ladbury JE, Bell JI, Jakobsen BK, van der Merwe PA. TCR binding to peptide-MHC stabilizes a flexible recognition interface. Immunity. 1999;10:357–365. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankild S, de Boer RJ, Lund O, Nielsen M, Kesmir C. Amino acid similarity accounts for T cell cross-reactivity and for “holes” in the T cell repertoire. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naumov YN, Naumova EN, Hogan KT, Selin LK, Gorski J. A fractal clonotype distribution in the CD8+ memory T cell repertoire could optimize potential for immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:3994–4001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cibotti R, Cabaniols JP, Pannetier C, Delarbre C, Vergnon I, Kanellopoulos JM, Kourilsky P. Public and private V beta T cell receptor repertoires against hen egg white lysozyme (HEL) in nontransgenic versus HEL transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:861–872. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin MY, Welsh RM. Stability and diversity of T cell receptor repertoire usage during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection of mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1993–2005. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner SJ, Diaz G, Cross R, Doherty PC. Analysis of clonotype distribution and persistence for an influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Immunity. 2003;18:549–559. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veiga-Fernandes H, Walter U, Bourgeois C, McLean A, Rocha B. Response of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to antigen stimulation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:47–53. doi: 10.1038/76907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dutton RW, Bradley LM, Swain SL. T cell memory. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:201–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM. Altered peptide ligand-induced partial T cell activation: molecular mechanisms and role in T cell biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding YH, Baker BM, Garboczi DN, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Four A6-TCR/peptide/HLA-A2 structures that generate very different T cell signals are nearly identical. Immunity. 1999;11:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doherty PC, Zinkernagel RM. T-cell-mediated immunopathology in viral infections. Transplant Rev. 1974;19:89–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1974.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]