Abstract

The midbrain dorsal periaqueductal grey (DPAG) is part of the brain defensive system involved in active defense reactions to threatening stimuli. Corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) is a peptidergic neurotransmitter that has been strongly implicated in the control of both behavioral and endocrine responses to threat and stress. We investigated the effect of the nonspecific CRF receptor agonist, ovine CRF (oCRF), injected into the DPAG of mice, in two predator-stress situations, the Mouse Defense Test Battery (MDTB), and the Rat Exposure Test (RET). In the MDTB, oCRF weakly modified defensive behaviors in mice confronted by the predator (rat); e.g. it increased avoidance distance when the rat was approached and escape attempts (jump escapes) in forced contact. In the RET, drug infusion enhanced duration in the chamber while reduced tunnel and surface time, and reduced contact with the screen which divides the subject and the predator. oCRF also reduced both frequency and duration of risk assessment (stretch attend posture: SAP) in the tunnel and tended to increase freezing. These findings suggest that patterns of defensiveness in response to low intensity threat (RET) are more sensitive to intra-DPAG oCRF than those triggered by high intensity threats (MDTB). Our data indicate that CRF systems may be functionally involved in unconditioned defenses to a predator, consonant with a role for DPAG CRF systems in the regulation of emotionality.

Keywords: oCRF, DPAG, defensive behaviors, mice, MDTB, RET

1. Introduction

It has been consistently established that one of the fundamental brain regions responsible for the command of primitive flight and fight reactions elicited by proximal threat, acute pain and asphyxia is the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) matter [6,20]. The dorsal part (DPAG) of this structure has been implicated as a site of integration and modulation of the behavioral and autonomic expression of defensive reactions [5,20]. Electrical and chemical (e.g. excitatory amino acid) stimulation of the DPAG leads to explosive motor responses characterized by vigorous running and apparently- aimless vertical jumps in freely moving experimental animals [4,17,19]. These behaviors are proposed to reflect aversive responses due to their similarly with escape reactions induced by natural aversive stimuli, such as the exposure to a proximal predator [9]. Stimulation of the DPAG has been done in humans undergoing surgery and these patients reported intense fear along with autonomic reactions (e.g. tachycardia and hyperventilation) reminiscent of a full-blown panic attack [35].

Recently, McNaughton and Corr [31] have argued that brain structures controlling defensive behaviors related to anxiety (e.g. risk assessment and avoidance) and fear (e.g. flight) are categorically distinct entities, and these form parallel streams that are represented at all levels of these systems. According to these researchers behavioral responses related to anxiety would be mediated mainly by forebrain structures (e.g. pre-frontal cortex, septo-hippocampal system); however, the PAG and hypothalamus would be the lower-level components of this system. In fact, many lines of evidence suggest that besides fundamentally controlling fear-like responses [22], the DPAG controls responses related to anxiety, such as avoidance and risk assessment [18,32].

Several neurotransmitters have been implicated as mediators or modulators of the behavioral responses elicitable in the DPAG, including GABA, glutamate, serotonin, cholecystokinin (CCK) and neuropeptides such as opioid peptides [6,21]. A number of recent studies suggest a role for the neuropeptide corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) in anxiety and fear-related behaviors [3]. CRF is a 41-amino acid peptide that serves as the main hypothalamic factor stimulating corticotrophin (ACTH) release from the anterior pituitary and, in turn, glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex [46]. The behavioral effects of central administration of CRF mimic those seen in response to stress, such as place aversion, increased locomotor activity, and decreased sexual activity [41, 27,16]. Chronic activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis may have pathological consequences for the animal. In stressed animals, CRF administration potentiates these behaviors [15], whereas CRF antagonists administered intracerebroventricularly or to the central amygdala can block the behavioral effects of stress [7,44]. Albeck et al. [1] reported that stress-responsive subordinate rats and nonresponsive subordinate rats showed an increase in the CRF mRNA levels in the central amygdala compared to the control group, whereas responsive subordinate rats exhibited higher levels than the dominant rats.

CRF and the CRF-like peptide, urocortin, are also widely distributed in extrahypothalamic portions of the mammalian brain, as are a number of CRF-responsive receptor subtypes [23,37]. CRF receptor types include CRF1 and CRF2, which are differentially distributed within the brain. In addition, each receptor has a number of splice variants. Anatomical studies have identified several neural sites containing CRF-ergic neurons [43] and CRF receptors [47] including the basal nuclei of the amygdala, hippocampus, bed nucleus of stria terminalis, raphe nuclei and periaqueductal gray. It is important to note that these areas are involved in the processing of anxiety and fear states as well as nociceptive information [33]. Anatomical heterogeneity of CRF1 and CRF2 suggests the existence of functional differences between them [8,28]. Overall, evidence accumulated so far has been relatively consistent for a role of CRF1 in the modulation of anxiety-like behaviors but much less so for that of CRF2 [45].

Experimental evidence has demonstrated that intra-cerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of CRF increases anxiety-related behaviors in rodents [2,34]. In addition, transgenic mouse lines overexpressing CRF exhibited behavioral states resembling anxiety [24]. In order to clarify the neural circuitry underlying anxiogenic effects of intracerebroventricular (ICV) CRF, several studies have investigated the direct infusion of CRF into discrete brain structures (for review see [24]). In the DPAG infusion of CRF increased anxiety-like behaviors in the elevated plus maze test [29] while the CRF antagonist, α-helical CRF reduced anxiety-related behaviors in stress-experienced rats [30]. Although CRF1 receptor subtype might represent the primary target involved in the mediation of the anxiogenic-like effects of CRF [24], in rodents both CRF1 and CRF2 mRNA expression are found in periaqueductal gray [47].

Unconditioned threat stimuli such as encounters with a predator are widely used to provide measures of behavioral responses to threat and stress [12]. The present study was designed to investigate the effect of the nonspecific CRF receptor agonist ovine CRF (oCRF) injected into the DPAG of mice, in two different predator or stress situations, the Mouse Defense Test Battery (MDTB), and the Rat Exposure Test (RET). The MDTB involves direct confrontation of mouse subjects with a hand-held anesthetized rat (predator) that first approaches, then chases, and finally contacts the mouse. This test elicits a number of high magnitude behavioral defenses and has proved to be responsive to anxiety and panic-related drugs [11]. The RET [49] was designed to afford a less intense threat situation, in which a wire mesh prevents the predator (rat) from approaching or contacting the mouse subject, allowing the subject to seek or avoid the predator stimulus and thus regulate its own exposure to threat.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were male Swiss-Webster mice, obtained from Charles Rivers laboratories (St. Louis, MO). Upon arrival, all mice were single-housed in opaque polypropylene cages in a temperature controlled room (22 ± 1C°) with ad libitum access to food and water. The mice were acclimatized for 4–6 weeks until they reached a weight range of 30 – 40 g. All mice were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 am. A total of 5 male Long-Evans rats were used as predator stimuli during the course of the study.

2.2. Drugs

Ovine Corticotrophin Releasing Factor (oCRF) was obtained from Max-Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine, Gottingen, Germany and dissolved in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The dose used (30 ng and 100ng /0.2µl) was based in previous studies [42,50]. The CSF solution was used as the vehicle compound.

D-Amphetamine sulfate (Research Biochemicals, MA) was dissolved in sterile physiological saline and administered i.p to rats at a single dose of 5.0 mg/kg 15 min prior to placement into the rat exposure chamber. This procedure was used to facilitate the maintenance of motor activity and interest in the mouse subject throughout the course of a 10-min trial duration.

2.3. Surgery

Mice were implanted unilaterally with an 8 mm stainless-steel guide cannula (26-gauge) under sodium pentobarbital (90 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia. The guide cannula was fixed to the skull using dental cement and jewelers’ screw. Stereotaxic coordinates for the dorsal PAG were 4.16 mm posterior to the bregma, 1.32 mm lateral to the midline and 2.23 mm ventral to the skull surface, with the guide cannula angled 26° to the vertical. A dummy cannula inserted into the guide cannula at the time of surgery, served to reduce the incidence of occlusion. To prevent accumulation of salivatory and bronchial secretions, 0.01 mg/kg subcutaneous (s.c.) glycopyrrolate (Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Shirley, NY), was administered fifteen minutes before surgery. Upon removal from stereotaxic apparatus mice were administered 1 ml 0.9% saline s.c. in order to prevent dehydration.

2.4. Intracerebral drug administration

Following a 1-week recovery period, mice were transferred from the main holding area to the laboratory and left undisturbed for 1 h prior to drug administration. Each mouse was lightly restrained and a 32-gauge injection cannula (1.0 mm longer than the guide cannula) was inserted into the guide cannula, the injector connected via PE-10 polyethylene tubing to a 10 µl Hamilton microsyringe. The solution administration was controlled by infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Inc. USA) programmed to deliver a volume of 0.2 µl over a period of 30 s. The injector remained in place for an additional 30 s (before slow removal) to allow for maximum drug infusion. Confirmation of successful infusion was obtained by monitoring the movement of small air bubble in the PE-10 tubing. Immediately following drug infusion, each animal was returned to its home cage, brought into the testing room and left undisturbed for 8 min prior to behavioral evaluation.

2.5. Apparatus

Behavioral responses were measured in the mouse defense test battery (MDTB) and the rat exposure test (RET) apparatus.

2.5.1. MDTB apparatus

The MDTB used in the present experiments was identical to that described for Griebel and coworkers [26](fig 1). The Mouse Defense Test battery is an oval runway, 0.40 m wide, 0.30 m high, and 4.8 m in total length, consisting of two 2.0-m straight segments joined by two 0.4-m curved segments, and separated by a median wall (2.0 m long × 0.30 m high). The apparatus was elevated to a height of 0.80 m from the floor to minimize the mouse’ visual contact with the experimenter. All parts of the apparatus were made of black Plexiglas. The floor of the runway was marked with white lines every 20 cm, to facilitate distance measurement. Activity was recorded using two ceiling-mounted video cameras.

Figure 1.

An overhead view of the MDTB apparatus.

2.5.2. RET apparatus

The rat exposure test (fig. 2) was developed and validated by Yang and coworkers [49] to facilitate measurement of risk assessment behaviors in mice. Testing procedures were conducted in a 46 × 24 × 21 cm clear polycarbonate cage (exposure chamber) covered with a metal lid. The exposure chamber was divided into two equal-sized compartments by a wire mesh screen. The home cage was a 7 × 7 × 12 cm box made of black Plexiglas on three sides and clear Plexiglas on the fourth side to facilitate videotaping. The home chamber was connected to the exposure cage by a clear Plexiglas tube tunnel (4.4 cm in diameter, 13 cm in length, 1.5 cm elevated the floor of the two chamber).One vertically mounted camera linked to a video monitor and DVD was used to record the experiment.

Figure 2.

An overhead view of the RET apparatus

2.6 Procedure

All testing was conducted during the light phase of the light/dark cycle under illumination of a 100-W red light. Each apparatus was cleaned with 20% alcohol and dried with paper towels in between trials.

2.6.1. Experiment 1. Mouse defense test battery

Seven days after surgery, each mouse was transported to the experimental room and left undisturbed for 60 min prior to testing. The mouse received an intra-PAG injection of CSF or oCRF (30ng or 100ng) and, 8 min. later, was run in the MDTB. The Long Evans rat used as predator was deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg, i.p) 10 min before the test session begins. The MDTB consists of the following subtests:

2.6.1.1. Pretest. Evaluation of motor response to drug treatment

Subjects were placed into the MDTB apparatus for a 3-min. familiarization period during which total line crossings and escape attempts (combined wall rears and jumps) were recorded.

2.6.1.2. Predator avoidance test

To ensure an initial separation of 2 m between the threatening stimulus and subject, the test began only when the subject was at one end of the apparatus. Immediately after the pre-test, a hand-held anesthetized rat was introduced into the opposite end of the open runway and brought up to the subject at an approximate speed of 0.5 m/s. Approach was initiated only if the subject was at a standstill with its head oriented toward the rat. Approach was terminated when contact with subject occurred, or the subject ran away from the approaching rat. If the subject fled, avoidance distance (the distance from the rat to the subject at the point of flight) was recorded. This procedure was repeated five times, with mean avoidance distance (cm) and number of avoidance calculated for each subject.

2.6.1.3. Chase/flight test

The hand-held rat was brought up to the subject at a speed of approximately 2.0 m/s. Chase was initiated only when the subject was at a standstill with its head oriented toward the rat, and completed when the subject had traveled a distance of 15.0 m (~ three laps). Total flight time (time taken to travel 15 m when the mouse was running forward) was recorded. Overall flight speed (m/s) and maximum linear flight speed (over a 2-m linear segment of the runway) were subsequently calculated for each animal. In addition, the number of Stops (pause in locomotion) and reversals (subject turned and ran in the opposite direction) were recorded.

2.6.1.4. Closed alley test

Upon closing two doors (80cm apart), one runway was converted into a closed straight alley in which the subject was trapped. The rat was introduced into one end of the straight alley. Trials began only when the subject faced the rat at a minimum of 60 cm stimulus-subject distance. Subjects were given three successive 30 sec. trials. During a trial, the number of approach-withdrawals (subject moves more than 20 cm from the closed door toward the rat, and immediately turns to the closed door) as well as voluntary contacts with the rat stimulus were recorded. Measures scored included freezing time, jump escape and jump attack frequencies. The results were expressed as means for each behavior for each animal.

2.6.1.5 Forced contact test

In this situation, the closed alley length was reduced to 40 cm. The experimenter quickly approached and touched the subject with a hand-held rat (five rapid contacts directed toward the subjects’ head). This procedure was repeated three times. During each trial, the number of vocalizations, defensive uprights, jump escapes and bites were recorded. The total for each dependent variable was summed over the three trials for each animal.

2.6.1.6 Posttest

Upon completion of the forced contact test, the alley doors were opened to permit locomotion around the circular runway. The subject’s activities were recorded for another 3 min. during which time the experimenter and the rat stimulus were out of sight. Line crossings and escape attempts (rearing and jump escapes) were recorded.

2.6.2. Experiment 2. Rat exposure test

One week after the MDTB procedure the subjects were tested in the rat exposure test (RET). Prior to the start of each trial, home cage bedding of each subject was placed on the floor of the home chamber as well as on the surface of the RET. The testing procedure consisted of two phases.

2.6.2.1. Phase 1: habituation

Each subject was allowed three daily habituation sessions during 3 consecutive days in the apparatus. The mouse was placed in the center of the surface and was allowed to explore freely for 10 min with no rat present.

2.6.2.2. Phase 2: Exposure test

When a mouse was placed into the center of the surface on Day 4, an amphetamine-treated male Long-Evans rat was immediately introduced behind the wire mesh. The followed behaviors were recorded during a 10 min trial.

The behavioral parameters comprised spatiotemporal and ethological measures. The spatiotemporal measures were frequency and time spent in the home chamber, tunnel, and on the surface. Time spent in contact with (including climbing) the wire screen barrier was taken as total (barrier) contact time. The ethological measures were frequency and duration of risk assessment (stretch attend postures, an exploratory posture in which the body is stretched forward but the animal’s hind paws remain in position, and stretched approach, in which the body is stretched while moving forward); freezing (complete cessation of movement except breathing); defensive burying (digging and/or pushing of the sawdust); and self-grooming.

2.7 Histology

Mice were sacrificed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and received an infusion of 10% methylene blue intra-DPAG (according to the microinjection procedure described above). The animals were perfused intra-cardially with 10 cc 0.9% formalin and their brain were removed from the cranial cavity and stored in 10% formalin/30% sucrose solution for at least 48 h before histological analysis. Mouse brain were coronally sectioned by a cryostat (50 µm) and microscopically verified with reference to the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin [38]. Data from animals with injection sites outside the DPAG were excluded from analysis.

2.8 Statistical Analyses

The behavioral data from the MDTB and rat exposure test were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA- vehicle, low dose and high dose as between-subjects factors) for parametrically distributed data, or Kruskal-Wallis for non-parametrically distributed data. Post hoc Duncan tests were conducted for significant treatment effects relative to control means (parametric), and Mann-Whitney U-tests (non-parametric). A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

2.9. Ethics

All procedures were run in accord with protocols approved by the University of Hawaii Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

3. Results

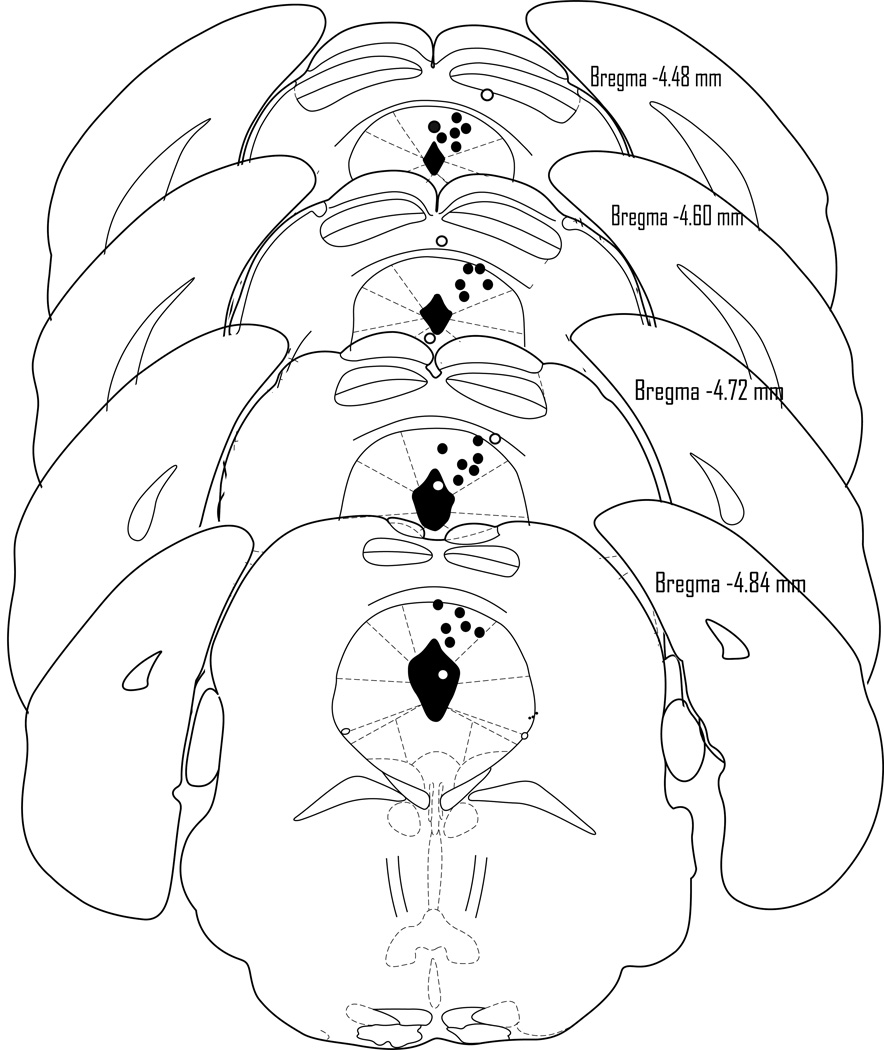

Histology confirmed that a total of 31 mice had accurate cannula placements in the DPAG and 6 had placements outside of the respective circumscribed area (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of microinfusion sites within (filled circle) and outside (blank circle) the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) of the mouse. The number of the filled circle in the figure is less than the total number of mice because of the overlaps.

3.1 Experiment 1. Mouse defense test battery

All behavioral data (means ± S.E.M and F value) from the mouse defense test battery are listed in table 1. The one-way ANOVA indicates significant main effects of oCRF injection on predator avoidance and forced contact tasks. Duncan post hoc test shows that the animals treated with oCRF (100 ng) exhibited higher avoidance distance as the reaction to the predator. In the forced contact test, Duncan test indicated that both doses of oCRF had effects on escape attempts (increase jump escapes) and defensive threats (decrease upright postures).

Table 1.

Effect of o-CRF infusions in the DPAG on behavioral responses of mice confronted with a rat in the mouse defense test battery.

| Behaviors | control | o-CRF 30 ng | o-CRF 100 ng | F(2,28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest activity | ||||

| Line crossing | 200.4 ± 19.5 | 187.4 ± 6.6 | 182.3 ± 15.7 | 0.39 |

| Escape attempts | 9.5 ± 2.1 | 9.1 ± 2.1 | 6.7 ± 2.3 | 0.47 |

| Predator avoidance test | ||||

| Avoidance distance (cm) | 45.7 ± 10.4 | 44.9 ± 6.7 | 75.4 ± 8.3* | 3.69 |

| Avoidance Frequency | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.89 |

| Chase/flight test | ||||

| Flight Speed (m/s) | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 1.11 |

| Max Speed (m/s) | 0.8 4± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 0.52 |

| Stops | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 1.78 |

| Reversals | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 6.7 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 0.62 |

| Closed Alley Test | ||||

| Approaches/withdrawals | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.30 |

| Contacts | 1.0± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.42 |

| Jump escapes | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.08 |

| Freezing (s) | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.04 |

| Forced Contact test | ||||

| Uprights | 12.4 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 1.3* | 8.1 ± 1.6* | 5.50 |

| Vocalization | 13.6 ± 0.4 | 13.4 ± 0.8 | 14.0 ± 0.9 | 0.13 |

| Bites | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 0.07 |

| Jump escapes | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 8.1 ± 1.3* | 7.0 ± 1.6* | 6.03 |

| Post test | ||||

| Line crossing | 179.5 ± 20.9 | 152.6 ± 14.0 | 184.3 ± 23.0 | 0.80 |

| Escape attempts | 27.0 ± 3.1 | 32.4 ± 3.7 | 22.4 ± 5.2 | 0.47 |

p<0.05 compared to control by Newman-Keuls test

3.2 Experiment 2. Rat exposure test

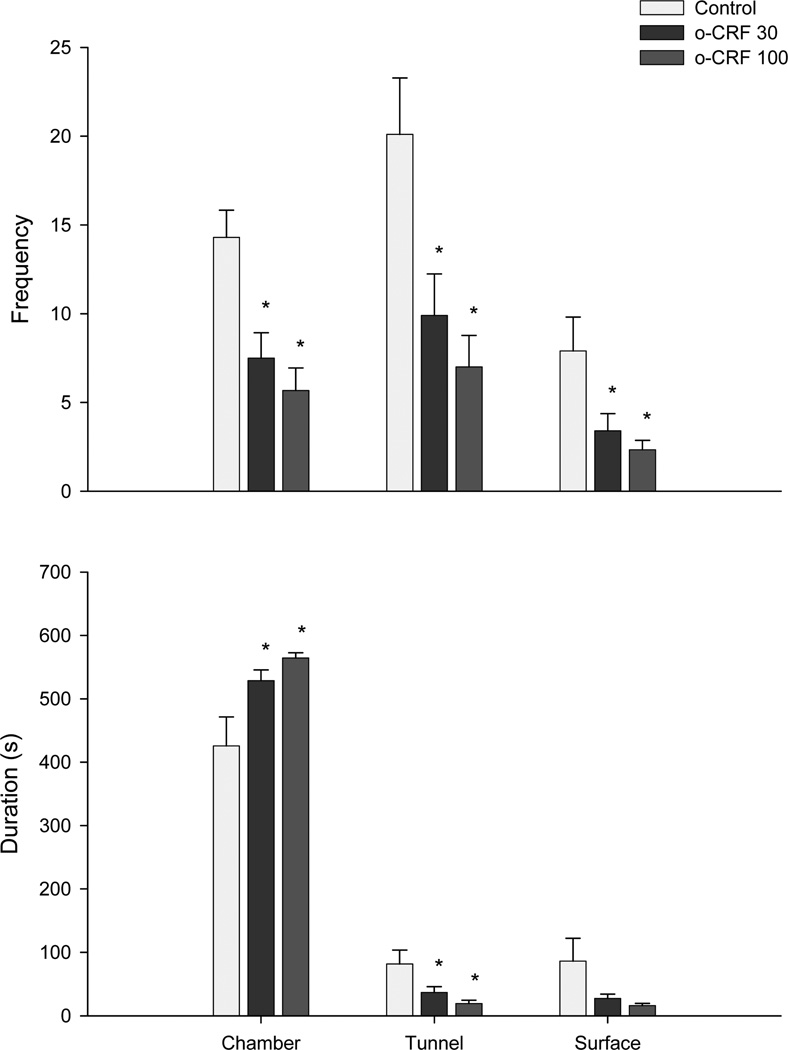

Spatiotemporal measures

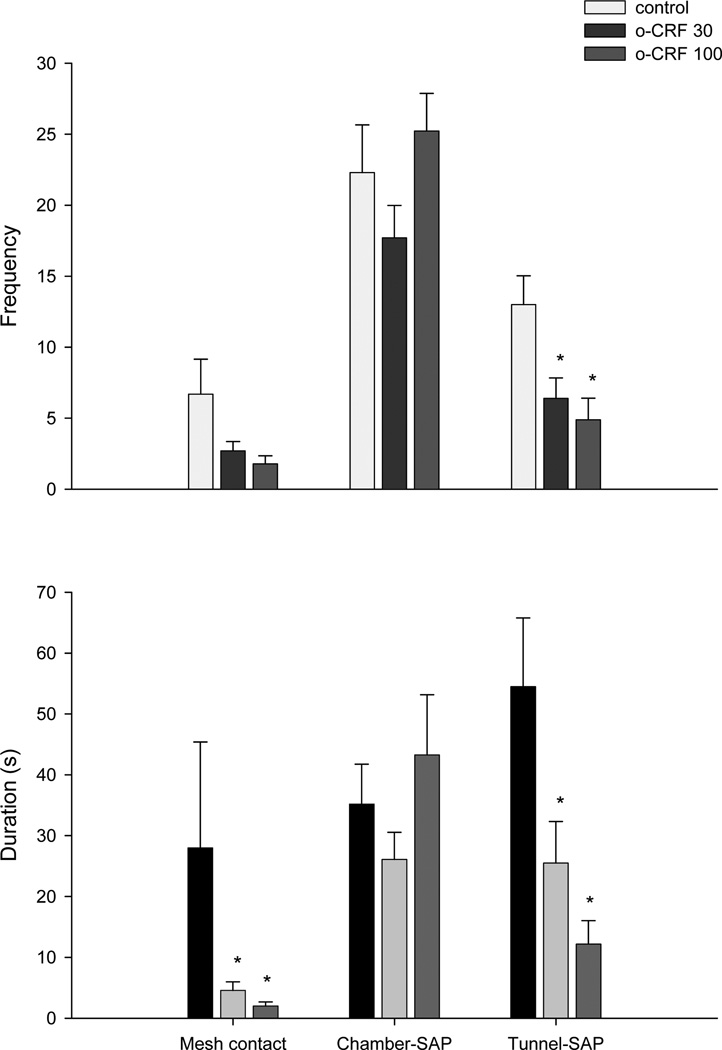

One-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of oCRF (30–100 ng) infusions on home chamber frequency (F(2,26)= 9.98, P< 0.001) and duration (F(2,26)= 6.00, P< 0.01), on tunnel frequency (F(2,26)= 7.32, P< 0.01) and duration (F(2,26)= 4.94, P< 0.01), and on surface frequency (F(2,26)= 5.09, P< 0.01) with a borderline effect on surface duration (F(2,26)= 2.99, P=0.07) (Fig 4). ANOVA also revealed a borderline effect on mesh contact frequency (F(2,26)= 2.87, P=0.07), while the Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA followed by Mann-Whitney U comparisons showed a significant effect on mesh contact duration (X2(2) = 8.18, P<0.01) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of oCRF injected into the dorsal PAG on the spatiotemporal (frequency upper panel and duration lower panel) defensive responses in the rat exposure test. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05 compared to control group.

Figure 5.

Effect of oCRF injected into the dorsal PAG on the spatiotemporal and ethological (frequency upper panel and duration lower panel) defensive responses in the rat exposure test. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05 compared to control group.

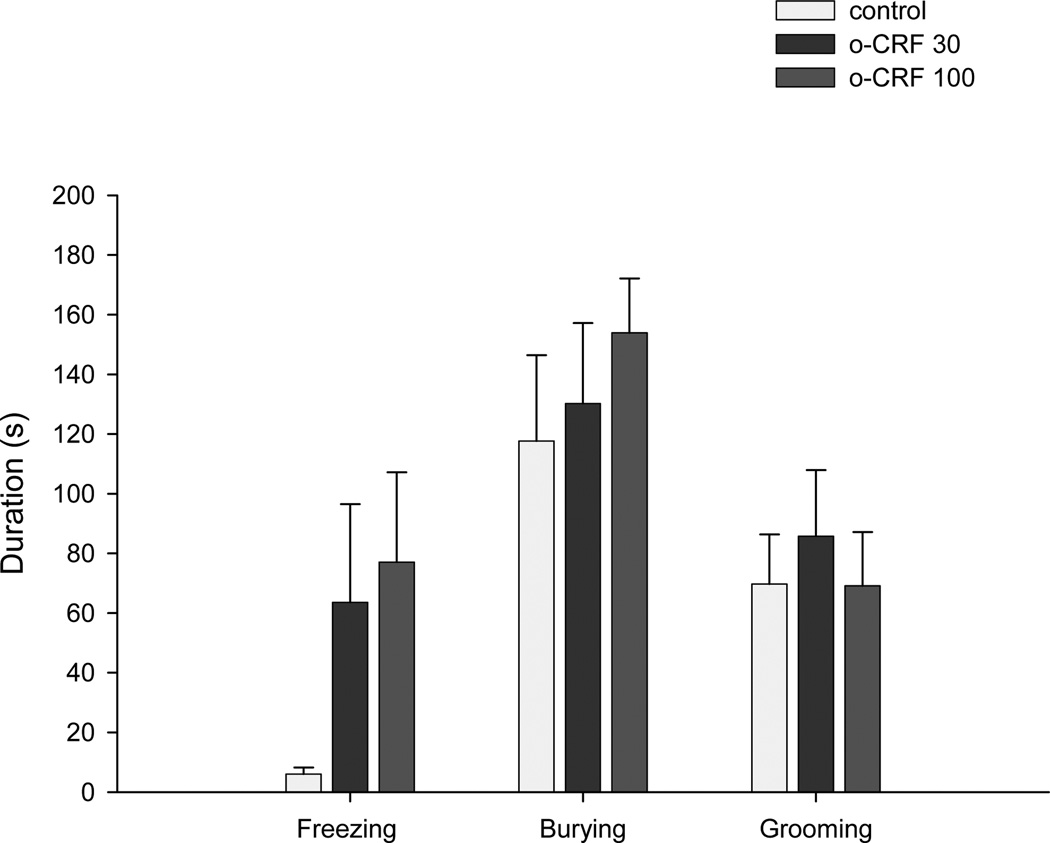

Ethological measures

Intra-DPAG infusions of oCRF decreased tunnel stretch attend frequency (F(2,26)= 6.53, P<0.01) and duration (F(2,26)= 6.96, P<0.01). No significant treatment effects were obtained for chamber stretched attend frequency (F(2,26)= 1.80, P>0.05) or duration (F(2,26)= 1.43, P>0.05) (Fig. 5); freezing duration (X2(2) = 4.16, P>0.05); burying duration (F(2,26)= 0.51, P>0.05); or grooming duration (F(2,26)= 0.24, P>0.05) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of oCRF injected into the dorsal PAG on the ethological (duration) defensive responses in the rat exposure test. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the behavioral effects of the peptide oCRF microinjected into the mouse DPAG in two different predator-stress situations, the Mouse Defense Test Battery (MDTB), and the Rat Exposure Test (RET). In the MDTB, oCRF weakly but consistently modified defensive behaviors in mice confronted by the predator, with an apparent emphasis on avoidance and escape. In this context only the highest dose of oCRF increased avoidance distance when the rat was approached. However, when mice were forced to contact the rat, both doses of oCRF potentiated escape attempts (jump escapes) while reduced defensive threats (upright posture). This pattern suggests a primary effect on escape, with a secondary effect on defensive threat, in that such threat is very dependent on the distance between prey and predator [10]: If the prey escapes prior to proximity/contact with the predator, a proportionate decline in defensive threat –as was obtained— would be expected. Thus the reduction in defensive threat is compatible with an overall enhancement of escape/avoidance following oCRF infusion. Earlier studies have demonstrated that acute peripheral administration of fluoxetine, imipramine or the benzodiazepine inverse agonist Ro 19-4603 all produced increases in avoidance and defensive threat behaviors, whereas chronic administration of fluoxetine or imipramine reduced these behaviors [25, 26]. These avoidance changes are consonant with a view that single acute administrations of SSRIs or tricyclic antidepressants can enhance the severity and frequency of some anxiety symptoms [25], as does Ro 19-4603 in preclinical models of anxiety [36], and support an interpretation of enhanced anxiety for the present finding of oCRF-enhanced avoidance in the MDTB. While these earlier studies found increased, rather than decreased, defensive attack (as occurred in the present study), they also failed to find increased escape in the forced contact test, such that proximity and contact of the subject with the predator was not reduced in treated animals; a factor important for the elicitation of attack toward the predator, and significantly reduced in the present study.

Our findings corroborate a consistent literature demonstrating that i.c.v. administration of CRF enhances behavioral responses in several animal models of anxiety (e.g., potentiated acoustic startle response, facilitated fear conditioning and enhanced shock-induced freezing and fighting behavior) [24]. Microinjection of CRF directly into specific sites such as the locus coeruleus, amygdala and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus has also been shown to intensify anxiety-related behaviors (for a review see [24]). Similarly, intra-DPAG infusion of CRF has been reported to produce anxiogenic-like behavior in the rat plus-maze test [29].

In contrast to many of these tests, the MDTB involves direct confrontation of the prey (mouse) with a hand-held anesthetized rat (predator) that first approaches, then chases, and finally contacts the mouse. This procedure leaves little escape possibility, providing a very intense threat and eliciting high levels of defensive responses in mice. Thus the relatively mild oCRF effects recorded in the present study may have been due to the high level of threat/stress elicited by the MDTB, which might have increased defensive responses to a level considered to be a ceiling effect.

In a recent MDTB study, Yang and colleagues [50] showed that i.c.v. injection of oCRF reliably potentiated most of the defensive behaviors evaluated in CD-1 strain of mice. oCRF robustly suppressed exploratory activities and increased risk assessment, freezing, avoidance, flight speed and jump escapes. These findings indicate that the MDTB can support enhanced defensiveness. However, these apparent contrasting differences between present results and those reported by Yang et al. [50] may be related to the different mouse strains used (Swiss-Webster × CD-1), injection sites (DPAG × i.c.v), as well as a substantial difference in the range of doses of oCRF (30–100ng here vs 450–950ng). Regarding the latter issue, it could be argued that higher doses of oCRF would produce stronger results when injected into the DPAG.

On the other hand, this view of a partial ceiling effect in the MDTB is compatible with the RET findings described in the Experiment 2. In the RET, connections of the mouse “home chamber” via a tunnel to a “surface area” where the predator is located allow the subject to seek or avoid the predator stimulus and thus regulate its own exposure to the threat. oCRF infusion into the DPAG consistently increased a number of measures of avoidance of the predator. For instance, both doses of oCRF increased home chamber time while reduced tunnel time, contact with the wire mesh and surface time (p=0.06). This avoidance effect appears to be relatively specific, i.e. although frequency and duration of risk assessment (stretch attend posture - SAP) were reduced in the tunnel compartment, relative frequency of SAP did not change. Behaviors like burying and grooming, which were mainly exhibited in the home chamber, were not different in both control and oCRF groups, thus suggesting that the drug did not provoke any motoric disruption. Although freezing durations appeared to increase in animals treated with oCRF this effect failed to reach an acceptable level of statistical significance.

Our results from RET confirm an overall enhancement of avoidance following intra-DPAG infusion of oCRF. These findings are in agreement with the results of Experiment 1, in which oCRF enhanced the avoidance distance as the reaction to the predator. These results also corroborate previous findings from Martins and coworkers [29] who have demonstrated that intra-DPAG infusion of CRF was able to increase the open arm avoidance in the EPM in rats. In that study, CRF microinjection reduced the percentage of entries and percentage of time spent on open arms of the EPM (anxiety indices), without significantly changing the number of enclosed arm entries, a measure usually considered to be an index of general activity [39].

A role of the DPAG in anxiety and, specifically, in panic attacks has been previously proposed [20]. The flight behavior or jumping that follows DPAG stimulation [17,40,48] as well as the reports from human patients undergoing neurosurgery [35] give support to this view. Present results with MDTB (Experiment 1) corroborate these evidences since intra-DPAG infusion of oCRF increased escape trials (jump escapes) during the predator approaches and contacts in the forced contact test. In front of this evidence, it could be suggested a CRFergic modulation within this midbrain structure on behaviors that have been related with panic attacks. In addition, the results from Experiment 2 strongly support previous findings [18] emphasizing the importance of the dorsal region of PAG in the modulation of a more subtle defensive behavior, such as risk assessment or threat avoidance. Taken together, these evidences are compatible with the McNaughton and Corr hypothesis [31] which suggests that the periaqueductal gray modulates behavioral responses related to anxiety such as risk assessment and avoidance besides fundamentally controlling fear-like responses [22].

It has been previously shown that antipredator defensive behaviors elicited in the RET respond to drugs effective against anxiety disorders such as diazepam and buspirone [13]. In other words, these drugs significantly reduced the spatiotemporal (avoidance) and ethological (risk assessment) measures. Hence, it would be reasonable to suggest a potential role for CRF systems in the DPAG in the regulation of emotionality. Indeed, an involvement of local CRF receptors on the emotional state has been confirmed by Martins and coworkers [30]. These researchers demonstrated that the enhancement of anxiety induced by forced immobilization was attenuated by intra-DPAG injection of alpha-helical-CRF9–41, a competitive CRF receptor antagonist, in rats exposed to the plus-maze test. These findings indicate a specific involvement of CRF-mediated neurotransmission in the DPAG on anxiety-related behaviors.

In conclusion, the two different predator-stress situations used in the present study - the MDTB and the RET- indicated that the patterns of defensiveness in response to low intensity threat (RET) are more sensitive to intra-DPAG oCRF than those triggered by high intensity threats (MDTB). Finally, present results suggest that CRF systems may be functionally involved in unconditioned defenses, acting in some of the same brain sites that have previously been investigated as components of an antipredator defense system [14].

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by CAPES Brazil and University of Hawaii-USA. E.F. Carvalho-Netto was recipient of CAPES and R.L. Nunes-de-Souza received a CNPq research fellowship.

References

- 1.Albeck DS, McKittrick CR, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ, Nikulina J, McEwen BS, Sakai RR. Chronic social stress alters levels of corticotrophin-releasing factor and arginine vasopressin mRNA in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4895–4903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04895.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin HA, Rassnick S, Rivier J, Koob GF, Britton KT. CRF antagonist reverses the "anxiogenic" response to ethanol withdrawal in the rat. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 1991;103(2):227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02244208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandler R, DePaulis A, Vergnes M. Identification of midbrain neurones mediating defensive behavior in the rat by microinjections of excitatory amino acids. Behav Brain Res. 1985;15:107–119. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(85)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandler R, DePaulis A. Midbrain periaqueductal gray control of defensive behavior in the cat and the rat. In: Bandler R, DePaulis A, editors. The midbrain periaqueductal gray matter. New York: Plenun Press; 1991. pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behbehani MM. Functional characteristics of the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;46(6):575–605. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00009-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berridge CW, Dunn AJ. A corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist reverses the stress-induced changes of exploratory behavior in mice. Horm Behav. 1987;21:393–401. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(87)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bittencourt JC, Sawchenko PE. Do centrally administered neuropeptides access cognate receptors? An analysis in the central corticotropin-releasing factor system. J Neurosci. 2000;20(3):1142–1156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01142.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard DC, Willians G, Lee EMC, Blanchard RJ. Taming wild Rattus novergicus by lesions of the mesencephalic central gray. Physiol psychol. 1988;(9):157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. Anti-predator defense as models of fear and anxiety. In: Brain PF, Blanchard RJ, Parmigiani S, editors. Fear and Defense. London: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1990. pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard DC, Griebel G, Blanchard RJ. Mouse defense behaviors: pharmacological and behavioral assays for anxiety and panic. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchard DC, Griebel G, Blanchard RJ. Conditioning and residual emotionality effects of predator stimuli: some reflections on stress and emotion. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychy. 2003;27(8):1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard DC, Yang M, Markham C, Farrohki CF, Pentkowski NS, Blanchard RJ, Griebel G. 2004 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2004. Diazepam and buspirone effects in c57bl/6j mice in the rat exposure test (ret) Program No. 784.3. Online. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchard DC, Canteras NS, Markham C, Pentkowski NS, Blanchard RJ. Lesions of structures showing FOS expression to cat presentation: effects on responsivity to, a Cat, Cat odor, and nonpredator threat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(8):1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Britton DR, Koob GF, Rivier J, Vale W. Intraventricular CRF enhances behavioral effects of novelty. Life Sci. 1982;31:363–367. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cador M, Ahmed SH, Koob GF, Le Moal M, Stinus L. Corticotropin-releasingfactor induces a place aversion independent of its neuroendocrine role. Brain Res. 1992;597:304–309. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91487-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho-Netto EF, Markham C, Blanchard DC, Nunes-de-Souza RL, Blanchard RJ. Physical environment modulates the behavioral responses induced by chemical stimulation of dorsal periaqueductal gray in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.022. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carobrez AP, Teixeira KV, Graeff FG. Modulation of defensive behavior by periaqueductal gray NMDA/glycine-B receptor. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25(7–8):697–709. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Scala G, Schmitt P, Karli P. Flight induced by infusion of bicuculline methiodide into periventricular structures. Brain Res. 1984;309:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deakin JFW, Graeff FG. 5-HT and mechanisms of defence. J Psychopharmacol. 1991;5:305–315. doi: 10.1177/026988119100500414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graeff FG. Neuroanatomy and neurotransmitter regulation of defensive behaviors and related emotions in mammals. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1994;27(4):811–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graeff FG. Serotonin, the periaqueductal gray and panic. Neurosci and Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:239–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray TS, Bingaman EW. The amygdala: corticotropin-releasing factor, steroids, and stress. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10(2):155–168. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griebel G. Is there a future for neuropeptide receptor ligands in the treatment of anxiety disorders? Pharmacol Ther. 1999;82(1):1–61. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griebel G, Blanchard DC, Agnes RS, Blanchard RJ. Differential modulation of antipredator defensive behavior in Swiss-Webster mice following acute or chronic administration of imipramine and fluoxetine. Psychopharmacol. 1995;120:57–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02246145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griebel G, Blanchard DC, Jung A, Blanchard RJ. A model of ‘antipredator’ defense in Swiss-Webster mice: Effects of benzodiazepine receptor ligands with different intrinsic activities. Behav. Pharmacol. 1995;(6):732–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee EH, Tang YP, Chai CY. Stress and corticotropin-releasing factor potentiate center region activity of mice in an open field. Psychopharmacol. 1987;93:320–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00187250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Vaughan J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. Urocortin III-immunoreactive projections in rat brain: partial overlap with sites of type 2 corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor expression. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):991–1001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00991.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins AP, Marras RA, Guimaraes FS. Anxiogenic effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the dorsal periaqueductal grey. Neuroreport. 1997;8(16):3601–3604. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199711100-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martins AP, Marras RA, Guimaraes FS. Anxiolytic effect of a CRH receptor antagonist in the dorsal periaqueductal gray. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12(2):99–101. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:2<99::AID-DA6>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNaughton N, Corr PJ. A two-dimensional neuropsychology of defense: fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(3):285–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendes-Gomes J, Nunes-de-Souza RL. Concurrent nociceptive stimulation impairs the anxiolytic effect of midazolam injected into the periaqueductal gray in mice. Brain Res. 2005;1047(1):97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66(6):355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momose K, Inui A, Asakawa A, Ueno N, Nakajima M, Fujimiya M, Kasuga M. Intracerebroventricularly administered corticotropin-releasing factor inhibits food intake and produces anxiety-like behaviour at very low doses in mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 1999;1(5):281–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nashold BS, JR, Wilson WP, Slaughter DG. Sensations evoked by stimulation in the midbrain of man. J Neurosurg. 1969;30(1):14–24. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.30.1.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicolas LB, Prinssen EP. Social approach-avoidance behavior of a high-anxiety strain of rats: effects of benzodiazepine receptor ligands. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:65–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0233-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olschowka JA, O'donohue TL, Mueller GP, Jacobowitz DM. Hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic distribution of CRF-like immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. Neuroendocrinol. 1982;35(4):305–308. doi: 10.1159/000123398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2rd ed. California: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodgers RJ, Johnson NJT. Factor analysis of spatiotemporal and ethological measures in the murine elevated plus-maze test of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;52:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00138-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schenberg LC, Bittencourt AS, Sudré ECM, Vargas LC. Modeling panic attacks. Neurosci Behav Rev. 2001;25:647–659. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sirinathsingjhi DJ, Rees LH, Rivier J, Vale W. Corticotropinreleasing factor is a potent inhibitor of sexual receptivity in the female rat. Nature. 1983;305:232–235. doi: 10.1038/305232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stiedl O, Meyer M, Jahn O, Ogren SO, Spiess J. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 and central heart rate regulation in mice during expression of conditioned fear. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(3):905–916. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Rivier J, Vale WW. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinol. 1983;36(3):165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swiergiel AH, Takahashi LK, Kalin NH. Attenuation of stressinduced behavior by antagonism of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in the central amygdala in the rat. Brain Res. 1993;623:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91432-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi LK. Role of CRF(1) and CRF(2) receptors in fear and anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25(7–8):627–636. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vale WW, Rivier C, Perrin M, Smith M, Rivier J. Pharmacology of gonadotropin releasing hormone: a model regulatory peptide. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1981;28:609–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Pett K, Viau V, Bittencourt JC, Chan RK, Li HY, Arias C, Prins GS, Perrin M, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. Distribution of mRNAs encoding CRF receptors in brain and pituitary of rat and mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428(2):191–212. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001211)428:2<191::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vianna DM, Brandao ML. Anatomical connections of the periaqueductal gray: specific neural substrates for different kinds of fear. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(5):557–566. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000500002. (Review). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang M, Augustsson H, Markham C, Hubbard DT, Webster D, Wall PM, Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. The rat exposure test: a model of mouse defensive behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(3):465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang M, Farrokhi C, Vasconcellos A, Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. Central infusion of ovine CRF (oCRF) potentiates defensive behaviors in CD-1 mice in the mouse defense test battery (MDTB) Behav Brain Res. 2006;171(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]