Abstract

Stress responses are known to modulate leukocyte trafficking. In the skin, stress was reported both to enhance and reduce skin immunity, and the chronicity of stress exposure was suggested as a key determining factor. We here propose a dual-stage hypothesis, suggesting that stress, of any duration, reduces skin immunity during its course, while its cessation is potentially followed by a period of enhanced skin immunity. To start testing this hypothesis, rats were subcutaneously implanted with sterile surgical sponges for four-hours, during or after exposure to one of several acute stress paradigms, or to a chronic stress paradigm. Our findings, in both males and females, indicate that numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, and their specific subsets, were reduced during acute or chronic stress, and increased after stress cessation. Studying potential mediating mechanisms of the reduction in leukocyte numbers during acute stress, we found that neither adrenalectomy nor the administration of beta-adrenergic or glucocorticoid antagonists prevented this reduction. Additionally, administration of corticosterone or epinephrine to adrenalectomized rats did not impact skin leukocyte numbers, whereas, in the blood, these treatments did affect numbers of leukocytes and their specific subsets, as was also reported previously. Overall, our findings support the proposed dual-stage hypothesis, which can be evolutionally rationalized and accounts for most of the apparent inconsistencies in the literature regarding stress and skin immunity. Other aspects of the hypothesis should be tested, also using additional methodologies, and its predictions may bear clinical significance in treatment of skin disorders related to hyper- or hypo-immune function.

Keywords: Stress, Immunity, Skin, Leukocyte, Trafficking, Redistribution, Epinephrine, Corticosterone, Adrenalectomy, Sponge

INTRODUCTION

Stress, both psychological and physiological, has long been considered a modulator of various immune functions (Bartrop et al., 1977; Ben-Eliyahu et al., 1999; Friedman et al., 1970; Wright et al., 1975). More recently, evidence began to accumulate regarding the robust effects of stress and stress hormones on the redistribution of leukocytes in the body, and on trafficking to specific immune compartments. For example, in humans, academic stress was associated with a simultaneous increase in numbers of circulating neutrophils, monocytes and CD8+ cells (Maes et al., 1999), and speech stress was found to directly increase numbers of T and NK cells in the blood (Marsland et al., 2002). Animal models have shown that administration of a β-adrenergic agonist (metaproterenol), doubled the number of circulating polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), and halved the number of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) 1–3 hours after drug administration (Shakhar and Ben-Eliyahu, 1998b). Increased glucocorticoid levels after stress were shown to correlate with such reduced lymphocyte and increased PMN numbers, while adrenalectomy or steroidogenesis inhibition almost completely eliminated these effects (Dhabhar, 2003). Metaproterenol administration (Goldfarb et al., 2009) and surgical stress (Benish et al., 2008) reduced the number of NK cells adhering to the lung endothelium, and a combined administration of a COX-2 inhibitor and a β-adrenergic blocker abolished this effect of surgery.

Stress impacts on leukocyte trafficking to the skin have recently received considerable attention. Evidence pointing toward these relations has emerged independently from various research domains, but no coherent picture has yet consolidated. On one hand, several studies suggested an enhancing effect of stress on leukocyte trafficking to the skin. Specifically, in mice, short-term stress given prior to immune challenge was reported to enhance leukocyte skin infiltration, increase delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) (Dhabhar, 2003), and potentiate immune resistance to squamous-cell carcinoma induced by UVB irradiation (Dhabhar et al., 2010). Additionally, several immune-related diseases such as psoriasis (Janowski and Pietrzak, 2008) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Aberer, 2010) are known to be aggravated by psychological stress in patients, hinting at a possible stress associated skin-immune activation. On the other hand, stress was suggested to reduce skin immunity. Specifically, stress has been repeatedly shown to causally reduce wound healing in animal models (Christian et al., 2006), and was associated with impaired wound healing in patients (Walburn et al., 2009)(Broadbent et al., 2003). Last, chronic restraint stress in mice increased susceptibility to UVB-induced skin cancer, while reducing numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Saul et al., 2005).

Several researchers suggested a distinction between “acute” or “short-term” stressors and “chronic” or “long-term” stressors (Dhabhar, 2003), with respect to their effect on skin immunity. According to this approach, acute stress enhances skin immunity, presumably as an adaptive response preparing the organism for a potential skin injury in “fight or flight” situations, while chronic stress weakens it (Dhabhar, 2009). This distinction can account for many of the apparent inconsistencies in the literature, including those described above; nonetheless, some findings still do not fit this notion. For example, an acute 15-minute exposure to social stress in humans actually reduced DTH-induced erythema, and impaired skin barrier function. Additionally, the same study also found that in people with PTSD, which is considered a chronic state of stress, these functions were enhanced (Altemus et al., 2006). In a different study (Bowers et al., 2008), mice which were exposed to chronic stress (28 daily treatments), developed a greater DTH response than their non-stressed peers. Another study in healthy married couples showed that after the induction of suction blisters, shortly discussing marital disagreements resulted in a slower wound healing process (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005).

Attempting to resolve some of these inconsistencies, we herein suggest the following hypothesis: both short- and long-term stressors reduce skin immunity during the stressful period, whereas cessation of stress, insofar as it occurs, is followed by a period of enhanced skin immunity (rebound), or at least an increase to baseline levels. To start testing this hypothesis, in the following experiments we measured the effects of several paradigms of acute stress and one paradigm of chronic stress, during their course and following their cessation, on the numbers of skin-trafficking leukocytes. Additionally, we studied the role of epinephrine and corticosterone in mediating changes in leukocyte skin trafficking during exposure to acute stressors.

It is logical to assume, and supported by the literature (Dhabhar, 2003), that trafficking of leukocytes to the skin is key to skin immunity, as the arriving leukocytes play a crucial role in all aspects of skin immunity (e.g., wound healing, defense against pathogens (Christian et al., 2006), and anti-tumor activity (Dhabhar et al., 2010)). One way of measuring leukocyte trafficking to the skin is by subcutaneously implanting sterile surgical sponges and assessing their leukocyte content. These gelatin sponges were previously used to study kinetics of leukocyte trafficking under various conditions (Viswanathan and Dhabhar, 2005), and their leukocyte content following implantation was shown to reflect the number of skin leukocytes (Fine et al., 2000; Sicard and Nguyen, 1996). Therefore, in the current study we used this approach to assess skin immunity, although clearly other methodologies could provide additional information, and be characterized by other advantages and limitations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male and female Fischer 344 rats (Harlan Laboratories, Jerusalem), were housed 4 per cage, with saw-dust bedding, under a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle at 22±1ºC, with free access to standard food and fresh water. Animals were acclimatized to our vivarium for at least 4 weeks, and were 12 to 20 weeks old at the beginning of experimentation (in any given experiment, all animals were of the same age). All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tel Aviv University.

Drugs

Nadolol (Sigma, Israel), a hydrophilic nonselective β-adrenergic antagonist, which does not cross the blood-brain-barrier, was dissolved in PBS and injected subcutaneously at 0.4mg/kg, immediately before sponge implantation.

Mifepristone (RU-486)(Sigma, Israel), a hydrophobic glucocorticoid and progesterone receptor antagonist, was ground and dissolved overnight in corn oil and injected subcutaneously at 25mg/kg, immediately before sponge implantation.

Epinephrine (Sigma, Israel), was first dissolved in PBS. In order to maintain a relatively constant absorption level, epinephrine was administered subcutaneously (1 mg/kg), immediately before sponge implantation, in a slowly absorbed emulsion (consisting of 4 parts of the PBS containing the active ingredient, 3 parts of mineral oil, and 1 part of mannide-monooleate – a non specific surface active emulsifier – all purchased from Sigma, Israel).

Corticosterone (Sigma, Israel), the active glucocorticoid in rats, was ground and dissolved overnight in corn oil and injected subcutaneously at 9mg/kg, immediately before sponge implantation. This dose induces high physiological levels of plasma corticosterone (500–800 ng/ml) for 4–5 hours per injection (Haim et al., 2003), which are similar to levels reached after exposure to environmental stressors (Shakhar and Blumenfeld, 2003).

Surgical sponge implantation and harvesting

Gelfoam absorbable gelatin sponges (Pfizer – Pharmacia & Upjohn Co., NY, USA) were cut under sterile conditions to a size of 2×1×0.5 cm. Before the implantation procedure, the rats were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane, and their dorsum was shaved and sterilized using ethanol. A 7 mm incision was made through the skin, 1 cm lateral to the spine on each side, at the midway between the front and the back leg. In each incision, a sponge soaked in PBS was inserted under the skin, 3cm cranially, between the superficial and the deep fascia. Afterwards, rats were left to recover at their home cages for at least 5 minutes before any additional procedure, and 4 hours later all rats were sacrificed, and the sponges were collected. We did not suture or close these superficial incisions, as this had no effect on trafficking in our preliminary studies (not shown) and caused unnecessary pain and discomfort for the animals. Nevertheless, we always found the incisions to have closed by themselves by the time of sponge harvesting.

General experimental procedures and counterbalancing

Rats were handled daily for 4 days prior to each experiment in order to reduce unwanted procedural stress, and were randomly allocated to groups. Exposure to stress and adrenalectomy procedures were counterbalanced across cages (i.e., conducted in different cages) in order to prevent unwanted stress in controls. Drug administration was counterbalanced within cages. Order of surgical sponge implantation and harvesting was always counterbalanced between the different experimental groups. In order to avoid confounding effects of various circadian rhythms (e.g., glucocorticoids), surgical sponges were always implanted at the same time in all groups (approximately 4 hours into the 12h light period), and harvested exactly 4 hours later. Blood samples for serum analysis and flow cytometry were collected by cardiac puncture within less than 3 minutes of approaching a cage, immediately before sponge retrieval. Sera were separated and frozen at −80ºC for later analysis of corticosterone levels.

Four-hour wet-cage stress paradigm

Rats were placed for 4 hours in standard transparent Plexiglas cages filled with 2 cm deep water, at room temperature, with free access to food and drinking water.

Four-hour restraint stress paradigm

Rats were placed for 4 hours in well ventilated Plexiglas cylinders which limit movement without hurting or pressuring the animals.

Chronic (25-day) stress paradigm

For 25 consecutive days, rats were exposed to daily four-hour stress sessions, alternating between the wet-cage and the restraint stress paradigms described above, ending on the 25th day (experiment day) with exposure to the wet-cage paradigm.

Adrenalectomy and sham operation

Rats were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and a 4cm midline abdominal incision was performed. Both adrenal glands were exposed and removed completely using standard surgical techniques. Sham-operated rats underwent the exact same procedure without removal of the adrenal glands. In order to expedite recovery from surgery, adrenalectomized rats were subsequently injected s.c. three times, 3 hours apart, with 1 mg/kg corticosterone/injection. Following surgery, and to ensure complete recovery, rats were kept in their home cages undisturbed for 4–6 weeks before entering experiments. To overcome the lack of mineralocorticoids, and to approximate normal levels of corticosterone, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and their circadian rhythms, the regular drinking water of adrenalectomized rats was replaced with 0.9% NaCl saline containing 15 mg corticosterone/liter. Previous studies showed that this method approximates normal circadian corticosterone levels (~20–100ng/L, Zagron and Weinstock, 2006, and unpublished data from our laboratory), as rats drink mostly during their first activity hours (Dhabhar and McEwen, 1999). Two hours before experimentation, and to ensure low physiological corticosterone levels, adrenalectomized rats were given only normal 0.9% saline without corticosterone as their drinking water.

Experimental laparotomy

To simulate stress caused by surgery, in experiment 4, rats underwent laparotomy. This procedure has been described elsewhere (Bravo-Zhivotovskii et al., 2005). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and a 4cm midline abdominal incision was performed. The small intestine was externalized, rubbed with a PBS-soaked gauze pad and left hydrated with a PBS-soaked gauze pad for 40 minutes. Finally, the intestine was internalized and the abdomen sutured and cleaned.

Sponge leukocyte extraction

After retrieval of implanted surgical sponges, each sponge was placed in a tube containing 4 ml PBS, and thoroughly squeezed with forceps for at least 100 times. The entire content of the tube was then passed through a 40 micron filter and concentrated (300×g for 10 minutes) to a volume of 100 μl for flow cytometric analysis.

Counting leukocytes and identifying subsets using flow cytometry

FACS analysis was used to assess numbers of leukocytes and specific subsets in the blood and in the surgical sponges. At least 30,000 events from each sample were analyzed. Lymphocytes and granulocytes were identified based on their forward and side scatter properties. Within the blood lymphocyte population and within the sponge-infiltrating total leukocytes, T cells were identified as CD5 positive (using PE-conjugated anti-rat-CD5, eBioscience), NK cells were identified as CD161bright lymphocytes (using FITC-conjugated anti-CD161 labeling, Serotec) (Shakhar and Ben-Eliyahu, 1998a), and NKT cells were identified as positive for both markers. Within total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, neutrophils were identified as CD161dim (Chambers et al., 1989). See Fig. 1 for illustration of cell populations. To assess the absolute numbers of cells per microliter of blood or sponge extract (for each specific leukocytes subset, and for total leukocytes), we added 600 polystyrene microbeads (20-μm, Duke Scientific, Palo Alto, CA) per μl of sample studied. Following cytometry, the formula: #CD5+/#microbeads×600 was used to calculate the number of CD5+ (T-cells) per microliter of sample. The same formula was used for each other subset of leukocytes, and for total leukocytes. The coefficient of variation for this method was found in our laboratory to be 6% for identical samples, and the approach was repeatedly used in different immune compartments (Goldfarb et al., 2009; Ben-Eliyahu et al., 2000; Benish et al., 2008).

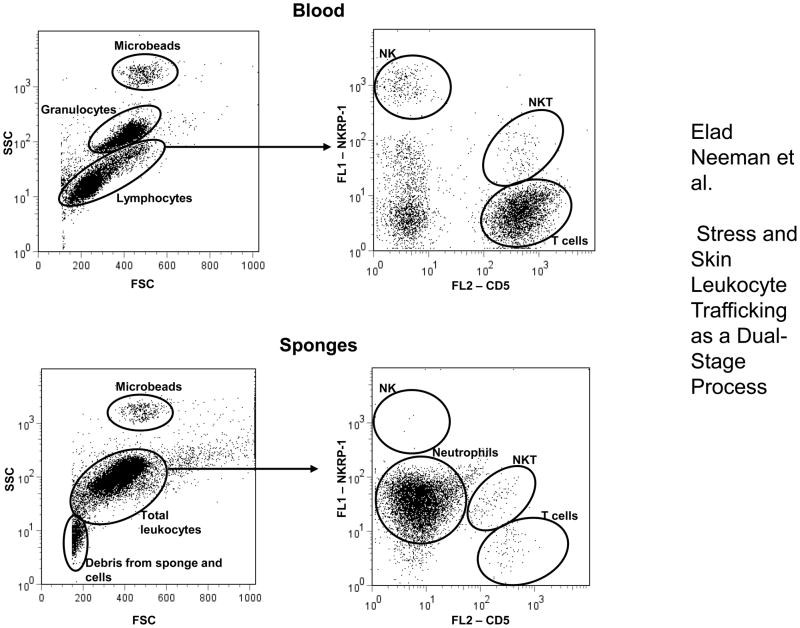

Figure 1. Illustration of cell populations in flow cytometric analysis.

Cell populations in blood and sponge samples are marked by ovals. Lymphocytes and granulocytes were identified based on their forward and side scatter properties. T cells were identified as CD5 positive, NK cells as CD161bright lymphocytes, and NKT cells as positive for both markers. Within sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, neutrophils were identified as CD161dim. Polystyrene microbeads were added to each sample and used to assess the absolute numbers of cells per sample studied (see Methods). At least 30,000 events from each sample were analyzed (the illustration shows a smaller number for clarity of presentation). “Debris from sponge and cells” does not contain CD161+ or CD5+ events, and does not form a coherent population when displayed on a CD5 by CD161 axes.

Corticosterone radioimmunoassay

A standard 125I competitive RIA kit (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) was used to measure corticosterone levels according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

One- or two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used in all studies to analyze numbers of leukocytes in sponges and in blood samples, and corticosterone levels. Fisher’s Protected Least Significant Differences (PLSD) post-hoc contrasts were used to test specific pair-wise differences, and employed only when significant group differences were indicated by ANOVA. For all analyses, p values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

PROCEDURES AND RESULTS

Experiments 1&2: Sponge-infiltrating-leukocyte numbers are reduced during a four-hour wet-cage stress exposure and elevated following stress cessation, in both male and female rats

Procedure

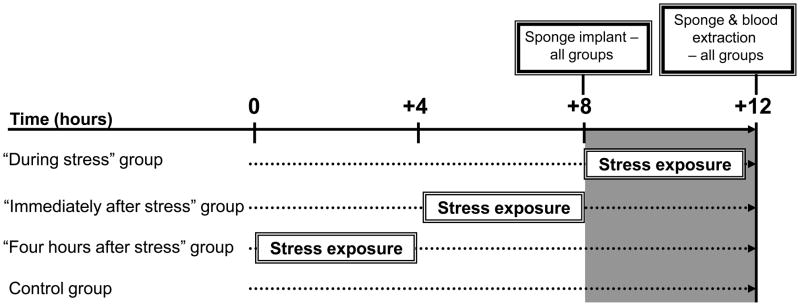

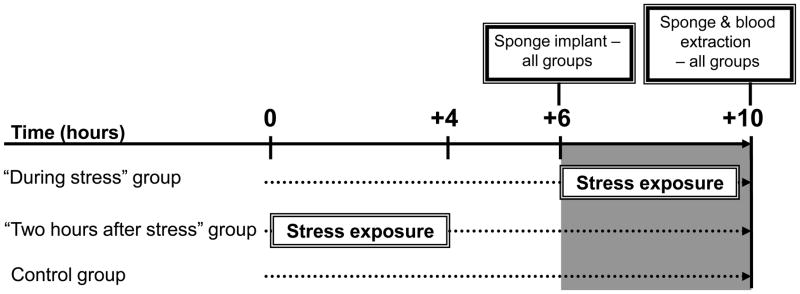

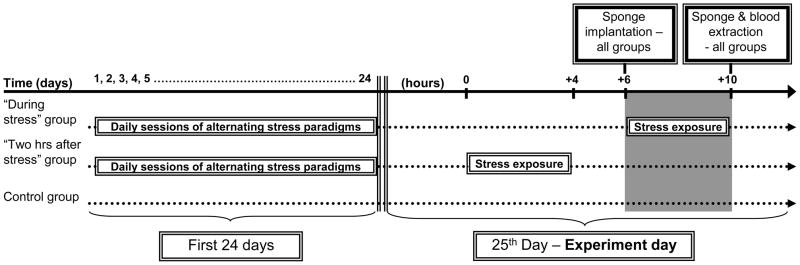

In the first experiment, male rats (n=20–21/group) were implanted subcutaneously with surgical sponges at: (i) the initiation of a four-hour wet-cage stress exposure, (ii) immediately after its cessation, or (iii) 4 hours after its cessation. See experimental design and timeline in Fig. 2. To study whether observed effects are sex-dependent, in the second experiment, female rats were similarly subcutaneously implanted with surgical sponges, either during (n=13), or 2 hours after (n=8) the four-hour wet-cage exposure. In the second and further experiments we wanted to have one “after stress” group, and therefore we chose the middle “2 hours after stress” time point. See experimental design and timeline in Fig. 3. In both experiments, control rats (n=20/group) were returned to their home cages immediately after implantation, for 4 hours. In the above and all following studies, sponges were implanted and harvested at the same time of the day in all experimental groups, to overcome potential confounding circadian rhythms (also see Fig. 2 & 3).

Figure 2. Experimental design and timeline for Experiment 1.

Figure 3. Experimental design and timeline for Experiment 2.

Results

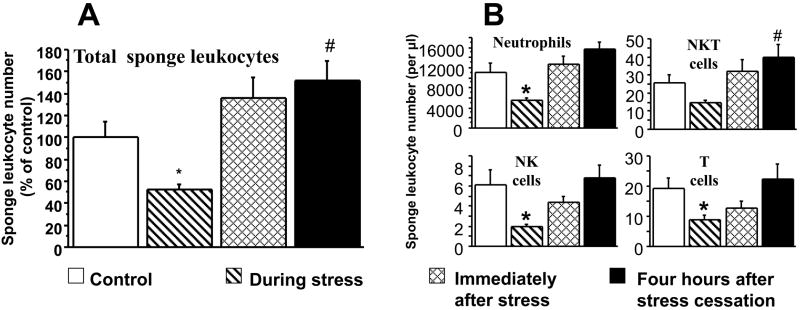

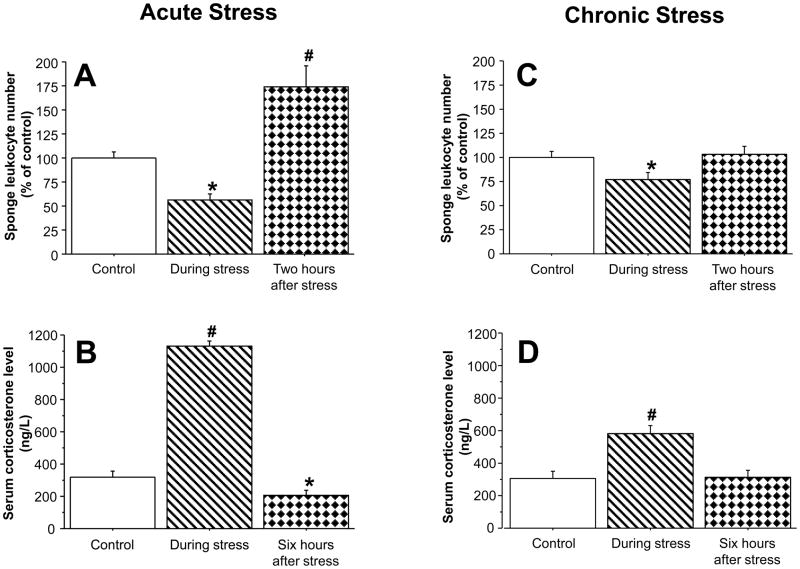

In Experiment 1 in male rats, ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(3,77)=8.919, p<0.0001), and significant pair-wise PLSD with the control group are marked with a-* (decrease) or # (increase). As seen in Fig. 4A, stress halved the number of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes during its four-hour course, compared to controls (PLSD, p=0.0253). In sponges implanted immediately after stress cessation, the number of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes was marginally increased (PLSD, p=0.097) and was significantly increased (PLSD, p=0.0167) in sponges implanted 4 hours after the cessation of the stress paradigm. Looking into specific subsets (neutrophils, NK cells, T cells, NKT cells) within total infiltrating leukocytes, Fig. 4B shows that although neutrophils account for almost all of the sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, the small numbers of sponge-infiltrating NK, T and NKT cells also show a similar reduction during stress and return to baseline levels following stress, although not always exceeding baseline levels. In Experiment 2 (females), ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(2,38)=24.873, p<0.0001). As seen in Fig. 5A, similar effects were observed in females, where sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers halved during the four-hour stress exposure (PLSD, p=0.0019), and significantly increased in sponges implanted two hours after stress cessation (PLSD, p<0.0001). Examining specific leukocyte subsets, revealed a similar pattern to that evident in males (See Table 1). Corticosterone levels in these females mirrored the sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers (ANOVA F(2,40)=202.9, p<0.0001), increasing (nearly quadrupling) during the four-hour stress session (PLSD, p<0.0001), and decreasing beyond baseline levels at six hours after its cessation (i.e., at time of sponge retrieval; PLSD, p=0.0459; see Fig. 5B).

Figure 4. Effects of a four-hour wet-cage stress exposure – during its course, immediately after, or four-hours after its cessation, on numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes and their specific subsets in male rats.

During its course, wet-cage stress significantly reduced numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes (A), and specific subsets (B). These numbers returned to baseline immediately following stress, and significantly increased four-hours following its cessation. Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant decrease from the control group and # indicates a significant increase.

Figure 5. Effects of an acute four-hour stress paradigm and a chronic stress paradigm, during their course, or two-hours after their cessation, on total sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers and on serum corticosterone levels.

Stress exposure, during its course, significantly reduced numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, in both the four-hour wet-cage paradigm (by ~50%, A), and the chronic alternating paradigm (by ~20%, C). At the endpoint of stress exposure corticosterone serum levels were significantly increased in both paradigms (by four-fold in the acute paradigm, B; by twofold in the chronic one, D). In sponges implanted two-hours following stress cessation, leukocyte numbers were significantly increased to baseline levels in the chronic paradigm (B) and exceeded these levels in the acute (A) stress paradigm. Six hours after stress cessation, corticosterone levels were reduced beyond baseline levels in the acutely stressed rats (C), and retured to baseline levels in the chronically stressed rats (D). Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant decrease from the control group and # indicates a significant increase.

Table 1.

Effects of four-hour wet-cage stress exposure, during its course, or two hours after its cessation on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocyte subsets.

| Neutrophils | T cells | NK Cells | NKT cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100.0 (10.9) | 100.0 (13.0) | 100.0 (13.2) | 100.0 (16.4) |

| During stress | 62.7 (10.9)* | 36.9 (6.8) | 59.7 (9.3) | 45.6 (7.2)* |

| stress cessation | 185.3 (23.9)# | 109.2 (38.6) # | 107.1 (25.9) | 115.0 (23.7) |

Data are presented as mean percent from control levels (SEM).

indicates a significant decrease from the control group and

indicates a significant increase.

Experiment 3: Sponge-infiltrating-leukocyte numbers are reduced during chronic stress exposure and increase to control-levels following stress cessation

Female rats were subjected to a chronic stress paradigm along 25 consecutive days (see Methods). On the 25th day, rats were subcutaneously implanted with surgical sponges either during (n=11), or 2 hours after (n=15) a four-hour wet-cage exposure. See experimental design and timeline in Fig. 6. Control rats (n=16/group), not previously exposed to stress, were returned to their home cages immediately after implantation.

Figure 6. Experimental design and timeline for Experiment 5.

Daily four-hour stress sessions along the first 24 days alternated between the “wet-cage” and the “restraint” stress paradigms (see Methods).

ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(2,39)=3.438, p=0.0421). As seen in Fig. 5C, in chronically stressed rats, sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers were reduced during stress, to 80% of control levels (PLSD, p=0.0349). Numbers increased to control levels (PLSD, p=0.018 between the “during” and “after” stress groups) in sponges implanted two hours after chronic stress cessation. Examining specific leukocyte subsets, revealed a similar pattern for neutrophils, T, and NK cells, although not always reaching statistical significance (See Table 2). As seen in Fig. 5D corticosterone levels in these rats mirrored the infiltrating leukocyte numbers (ANOVA F(2,39)=9.936, p=0.0003), approximately doubling during the stress session (PLSD, p<0.0001), and returning to control levels at six hours after stress cessation (i.e., time of sponge retrieval).

Table 2.

Effects of a chronic stress exposure, during its course, or two hours after its cessation on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocyte subsets.

| Neutrophils | T cells | NK Cells | NKT cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100.0 (6.9) | 100.0 (15.2) | 100.0 (11.9) | 100.0 (23.6) |

| During stress | 72.2 (9.2)* | 70.5 (11.0) | 63.7 (9.6) | 93.4 (24.0) |

| Two hrs after stress cessation | 102.8 (9.6) | 95.3 (9.0) | 107.6 (15.7) | 86.1 (16.7) |

Data are presented as mean percent from control (SEM).

indicates a significant decrease from the control group.

The behavior of rats seemed to significantly change along the 25-day period, although we did not quantify it. Qualitatively, while during the first days, rats defecated markedly, resisted entering the restraint cylinders, and seemed anxious (as was also observed in Exp. 1&2), during the last days these behaviors had almost completely dissipated. These subjective observations concur with the only two-fold increase in corticosterone levels (from ~300 to ~600 ng/dL), evident during the last stress session (on day 25), compared to a four-fold increase (from ~300 to ~1200 ng/dL) in experiments employing a single (acute) stress session (e.g., Experiment 2).

Experiments 4&5: Four-hours of surgical or restraint stress exposure reduced numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes during their course

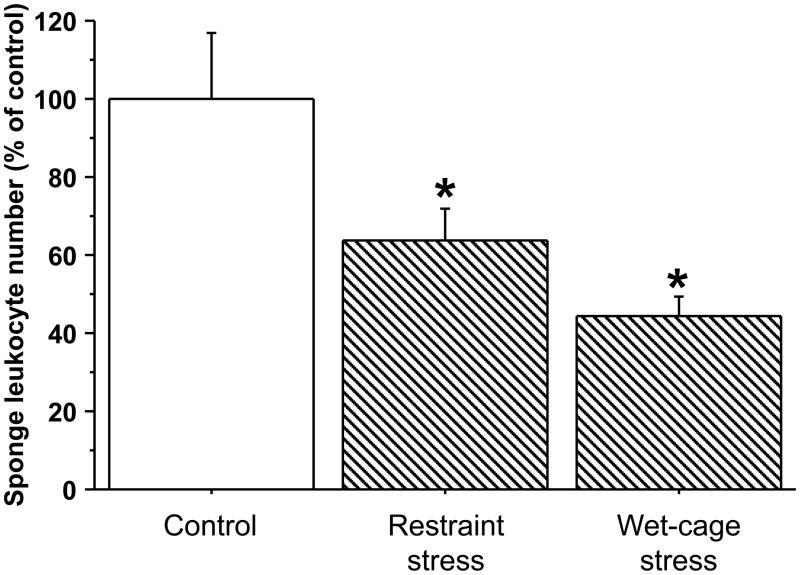

In order to show that the reduced numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, observed during acute stress, are not limited to a specific stress paradigm, rats were exposed to surgical stress and to restraint stress, and compared to control rats and to rats exposed to the wet-cage stress paradigm.

Exp. 4 - male rats (n=9–10/group) were implanted with surgical sponges and immediately subjected to four hours of either wet-cage stress, restraint stress, or served as controls (returned to their home cages immediately after implantation). ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(2,25)=6.683, p=0.0047). As indicated in Fig. 7, both restraint (PLSD, p=0.0458) and wet-cage (PLSD, p=0.013) stress paradigms significantly reduced numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes during their course. Specific leukocyte subsets (see Exp. 1) showed similar patterns (See Table 3).

Figure 7. Comparing the effects of four-hour wet-cage and restraint stress paradigms, during their course, on sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers, in male rats.

Both wet-cage stress and restraint stress, during their course, significantly reduced numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, compared to controls. Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant difference from the control group.

Table 3.

Effects of four-hour restraint stress or wet-cage stress exposure, during its course, on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocyte subsets.

| Neutrophils | T cells | NK Cells | NKT cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100.0 (14.4) | 100.0 (26.4) | 100.0 (26.2) | 100.0 (13.6) |

| Restraint stress | 20.3 (7.7) | 67.1 (19.6) | 67.8 (20.8) | 69.0 (9.5) |

| Wet-cage stress | 22.6 (4.9)* | 39.8 (7.6)* | 35.7 (6.9) | 56.2 (4.2)* |

Data are presented as mean percent from control (SEM).

indicates a significant decrease from the control group.

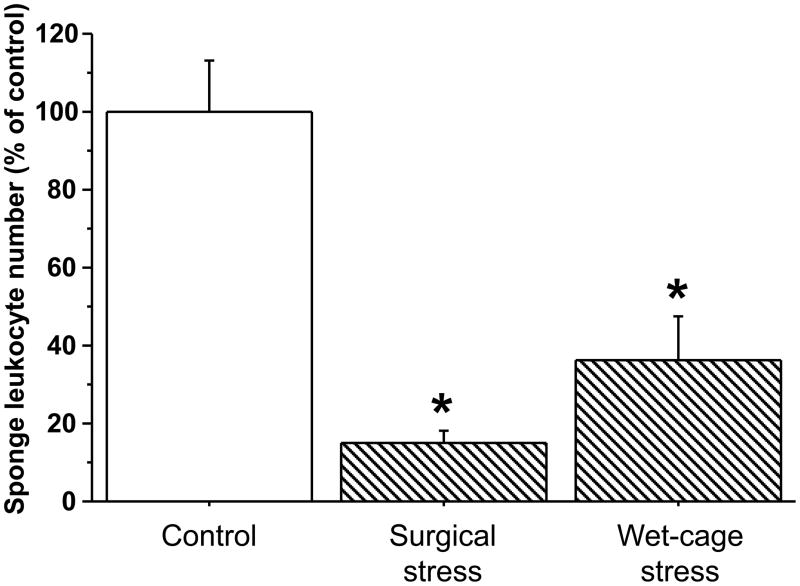

Exp. 5 - Female rats (n=6–8/group) were implanted with surgical sponges for four hours (i) while undergoing a wet-cage stress procedure or (ii) immediately after experimental laparotomy, or (iii) served as controls. ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(2,18)=18.604, p<0.0001). As indicated in Fig. 8, both wet cage (PLSD, p=0.005) and surgical (PLSD, p<0.0001) stress paradigms significantly reduced numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes. Specific leukocyte subsets (see Exp. 1) showed similar patterns (see Table 4).

Figure 8. Comparing the effects of four-hour wet-cage and surgical stress paradigms, during their course, on sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers, in female rats.

Both wet-cage stress and surgical stress, during their course, significantly reduced numbers of total sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, compared to controls. Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant difference from the control group.

Table 4.

Effects of four-hour surgical stress or wet-cage stress exposure, during its course, on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocyte subsets.

| Neutrophils | T cells | NK Cells | NKT cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100.0 (12.9) | 100.0 (12.4) | 100.0 (43.0) | 100.0 (16.4) |

| Surgical stress | 13.9 (2.6)* | 42.7 (9.9)* | 37.1 (16.9) | 29.1 (5.0)* |

| Wet-cage stress | 34.2 (11.2)* | 70.0 (12.3) | 43.4 (16.4) | 47.7 (7.5)* |

Data are presented as mean percent from control (SEM).

indicates a significant decrease from the control group.

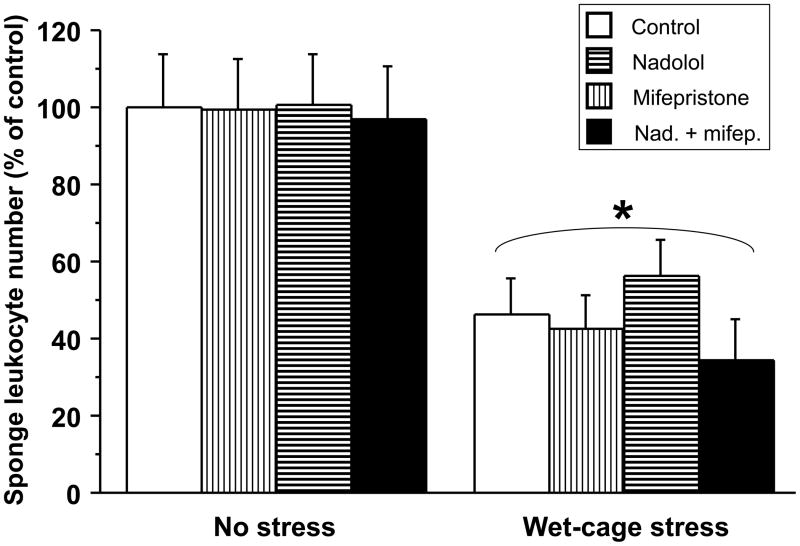

Experiment 6: Antagonists to the beta-adrenergic (nadolol) or the glucocorticoid (mifepristone) receptors, or their combination, do not block the reduction in numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes during a four-hour wet-cage stress exposure

Female rats (n=9–10/group) were implanted with subcutaneous surgical sponges and subjected to the four-hour wet-cage stress procedure, or served as controls. Each group was further subdivided into four sub-groups, receiving either nadolol, mifepristone, both drugs, or their vehicles, immediately before stress. These doses and schedule were found effective in our previous studies in blocking effects of stress or surgery on different modalities of immunity (Naor et al., 2009, and unpublished data from our lab).

Two-way ANOVA (stress vs. control × drug administration) indicated a significant main effect for stress exposure (F(1,67)=43.525, p<0.0001), without an effect for drug or an interaction. As seen in Fig. 9, stress halved the number of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes. No drug or drug combination affected the observed stress-induced reduction or altered baseline levels of infiltrating leukocytes.

Figure 9. Effects of a beta-adrenergic or a glucocorticoid blockade (employing nadolol or mifepristone) on the impact of a four-hour wet-cage paradigm on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes.

Wet-cage stress significantly reduced numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes during its course. Nadolol, mifepristone, or their combination, did not block this effect, nor changed baseline levels, compared to vehicle controls. Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant difference from the control group.

Experiment 7: The effects of four-hour stress exposure, or the administration of corticosterone or epinephrine in adrenalectomized rats: alterations in numbers of sponge-infiltrating and circulating leukocytes

Female rats (n=9–11/group) underwent adrenalectomy or sham operation. Adrenalectomized rats were maintained on 0.9% saline supplemented with corticosterone to maintain low physiological serum levels (see methods for details). Six weeks later, sham and adrenalectomized rats were implanted with surgical sponges before being subjected to a wet-cage stress procedure or serving as home-cage controls.

In normal rats, epinephrine administration was reported to elevate ACTH levels (Giguere and Labrie, 1983), and epinephrine levels were shown to be influenced by endogenous corticosterone secretion (Wurtman, 2002). In order to study the exclusive effects of each of these stress hormones, two additional groups of non-stressed adrenalectomized rats were administered with either epinephrine (1 mg/kg) or corticosterone (9 mg/kg) immediately after sponge implantation. All other groups received vehicle injections.

Numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes

ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(5,55)=12.513, p<0.0001). As seen in Fig. 10, stress reduced sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers by approximately 60 percent in both adrenalectomized and sham operated rats (PLSD, p<0.001 in both), while adrenalectomy itself had no significant impact. Additionally, administration of epinephrine or corticosterone to adrenalectomized rats had no effect on total sponge-infiltrating leukocyte numbers. Effects on specific sponge-infiltrating leukocyte subsets were similar and are described in Table 5.

Figure 10. Effects of a four-hour wet-cage paradigm, or of administration of epinephrine or corticosterone in adrenalectomized rats, on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes.

Wet-cage stress, during its course, significantly reduced numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes both in sham-operated and in adrenalectomized (ADX) rats. In contrast, administration of epinephrine or corticosterone to adrenalectomized rats did not affect these numbers. Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant difference from the control group.

Table 5.

Effects of four-hour wet-cage stress exposure, during its course, on adrenalectomized or sham-operated rats, or of the administration of corticosterone or epinephrine in adrenalectomized rats, on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocyte subsets.

| Neutrophils | T cells | NK Cells | NKT cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham-Control | 100.0 (14.4) | 100.0 (20.6) | 100.0 (22.8) | 100.0 (12.6) |

| Sham-Stress | 37.4 (8.6)* | 22.8 (2.3)* | 11.9 (3.4)* | 77.8 (21.0) |

| ADX-Control | 119.1 (13.1) | 102.9 (19.2) | 117.3 (27.1) | 154.5 (18.9) |

| ADX-Stress | 23.4 (5.0)* | 60.4 (11.4) | 28.2 (8.7)* | 101.6 (18.9) |

| ADX-Epinephrine | 114.4 (7.4) | 82.8 (13.9) | 108.6 (26.2) | 220.0 (38.5) |

| ADX-Corticosterone | 119.1 (13.2) | 68.9 (12.2) | 105.1 (26.1) | 158.6 (28.6) |

Data are presented as mean percent from control (SEM).

indicates a significant decrease from the control group

Numbers of circulating leukocytes and their specific subsets

In contrast to the findings regarding sponge-infiltrating leukocytes, and as seen in Fig. 11, adrenalectomy abrogated the effects of stress on circulating leukocytes, and the administration of epinephrine and corticosterone had significant effects on lymphocyte and granulocyte numbers. Specifically, stress significantly reduced the numbers circulating lymphocytes (ANOVA F(5,57)=7.774, p<0.0001) in sham operated rats (PLSD, p=0.05), but adrenalectomy abrogated this effect. Adrenalectomy, irrespective of stress, increased baseline levels of circulating lymphocytes (PLSD, p<0.0001), and administration of either epinephrine (PLSD, p=0.0118) or corticosterone (PLSD, p=0.0139) to adrenalectomized rats, each reduced circulating lymphocyte numbers to levels of sham-operated controls. Looking into specific subsets of circulating lymphocytes, similar patterns were evident with respect to NK, NKT and T cells, and specific pair-wise significant differences are marked in Fig. 11. With respect to granulocytes, stress had no significant effect on their numbers in sham or adrenalectomized rats. Administration of epinephrine to adrenalectomized rats increased these numbers (ANOVA F(5,57)=4.359, p=0.002; PLSD, p=0.0314), whereas corticosterone administration had no effect.

Figure 11. Effects of a four-hour wet-cage paradigm, or of administration of epinephrine or corticosterone in adrenalectomized rats, on numbers of circulating leukocyte subsets.

Adrenalectomy (ADX) prevented the reduction in numbers of circulating lymphocytes caused during stress, and specific lymphocyte subset numbers (NK, NKT and T cells) were even increased in adrenalectomized stressed rats. Consistently, administration of epinephrine or corticosterone to adrenalectomized rats reduced numbers of circulating lymphocytes. Data are presented as mean + SEM. * indicates a significant decrease from the relevant control group and # indicates a significant increase.

To ascertain the completeness of the adrenalectomy, corticosterone levels were measured in all rats at time of sponge retrieval. ANOVA indicated significant group differences (F(5,57)=59.294, p<0.0001). Adrenalectomized rats showed very low levels of corticosterone (<50 ng/L) compared to sham operated rats (~200 ng/L; PLSD, p=0.008). Stress increased these levels (to an average of approximately 1000 ng/L), but only in sham operated rats (PLSD, p<0.001) (not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study offers a new perspective on the effects of stress on skin leukocyte trafficking, and suggests a dual-stage reaction to stress, consisting of an initial reduction in skin leukocyte numbers during the stressful period, and an enhancement of leukocyte numbers following stress cessation. In the current study, this pattern was observed in both male and female rats, employing various acute as well as chronic stress paradigms. We chose to use a four-hour sponge infiltration measure, rather than longer periods of assessment, as this enabled us to study effects of stress in defined time periods relative to stress initiation and cessation. Although in this four-hour measure, neutrophils constituted the great majority of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes (as expected, Soehnlein et al., 2009), the smaller numbers of lymphocytes and their subsets showed very similar patterns, suggesting a trafficking reaction to stress which is generally not subset-specific. It is also important to note that the skin wounding, which is required for sponge implantation, is inherent to the sponge infiltration approach, as is the subsequent exposure of active animals to a non-sterile environment. Notably, these conditions are also inherent to naturally occurring wounds; hence, our conclusions seem both relevant and limited to such settings.

According to the proposed dual-stage perspective, stress cessation is followed by an increase in skin leukocyte trafficking. This prediction is supported by the findings of all the studies reviewed in the Introduction that report enhancing effects of stress on skin-immunity. Indeed, in these studies, whether utilizing an acute or a chronic stress paradigm, the relevant immune measures were assessed after stress cessation. Additionally, the proposed dual-stage notion predicts reduced skin immunity when assessed alongside acute or chronic stress. With respect to chronic stress this prediction is consistent with existing literature (see Introduction) and with the results of Experiment 3 herein; With respect to acute stress, this prediction is supported by the current study employing various acute stress regimens, and by all studies reviewed in the Introduction which assessed skin immunity during acute stress. Not tested in the current study is the relation between the duration of an acute stressor and skin trafficking (i.e., whether more prolonged stressors than those used herein will have similar effects).

It is important to note that some stress paradigms (e.g. surgery) do not include a defined time-point of stress cessation, and therefore may not be followed by enhanced immunity. Additionally, it is clear that complex and/or repeated stress exposures, which often constitute chronic-stress paradigms, may involve long-lasting psychological impacts, such as habituation, conditioned fear, or learned helplessness. Consequently, in some settings it might be difficult to identify a skin immune-enhancement in the context of chronic stress paradigms. In the current study, habituation may explain the smaller reduction in sponge leukocyte numbers and the smaller increase in corticosterone levels, evident during the last stress session of the chronic paradigm (Exp. 3), compared to a similar stress session constituting the four-hour acute paradigm (Exp. 2).

Previous studies assessing the effects of stress on leukocyte redistribution in other compartments (e.g. blood, lungs) have repeatedly shown that these effects could be blocked by beta-blockers and/or steroidogenesis inhibitors (Avraham et al., 2010; Ben-Eliyahu et al., 2000; Benish et al., 2008; Dhabhar, 2003), and could be mimicked by direct administration of epinephrine or corticosterone (Enberg et al., 1986; Joyce et al., 1976; Van Dijk et al., 1979). Our results, regarding the impacts of acute stress during its course, also showed similar causative effects of these hormones with respect to the blood compartment (see Fig. 11), but surprisingly not with respect to the skin.

Specifically, adrenalectomy abolished the effects of stress on numbers of circulating lymphocytes, whereas in the same animals, adrenalectomy had no impact on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes or their specific subsets, including lymphocytes. Similarly, administration of epinephrine or corticosterone in adrenalectomized rats significantly altered numbers of circulating lymphocytes and granulocytes, but had no effect on numbers of sponge-infiltrating leukocytes or their specific subsets. Finally, beta-adrenergic or glucocorticoid blockade did not affect the impact of stress on skin trafficking. Together, these findings strongly suggest that corticosterone and epinephrine are not involved in the reduction of skin leukocyte trafficking during the four-hour acute stress sessions employed herein. These findings are not in contrast to those of Dhabhar and McEwen (1999) which did show the involvement of these hormones. This study addressed the role of these hormones after the cessation of an acute stress paradigm, rather than during stress, as in the current study.

The underlying hormonal mechanism(s) of the stress-induced reduction in leukocyte skin trafficking in the current study remain unresolved. One study (Gajendrareddy et al., 2005) pointed out the involvement of skin oxygenation in mediating reduced wound healing by stress, but a specific neuroendocrine mechanism was not reported. Future studies should address potential mediators of the stress response in reducing skin leukocyte trafficking. The sympathetic nervous system is a primary initiator of stress responses (Nance and Sanders, 2007), and is a natural candidate for this role, as it innervates all lymphoid organs and blood vessels, and as leukocytes express receptors for catecholamines (Landmann, 1992). However, since the reduced skin trafficking was not blocked in this study by adrenalectomy or by the systemic administration of a peripheral beta-blocker, only an alpha-noradrenergic pathway may mediate these effects of stress. Indeed, peripheral blood supply is controlled by sympathetic alpha-noradrenergic regulation (Joyner and Casey, 2009). Additional mediators may include endogenous opioids, as they are secreted by the pituitary gland, the gastrointestinal tract, leukocytes, and by the adrenal glands (Gilmore et al., 1990; Hadley and Haskell-Luevano, 1999). Opiates were shown to reduce skin DTH responses in rats (Pellis et al., 1986), and thus may have a direct or indirect effect on skin immunity. Serotonin may also be involved in these effects as its receptors are expressed on several leukocyte subsets and on some of the epithelial cells composing the skin (Thorslund and Nordlind, 2007). Finally, endocannabinoids may mediate stress effects on reduced skin immunity. CB2 receptors are expressed on leukocytes, and the endocannabinoid system was shown to modulate stress responses and to facilitate important immune regulating effects on cytokine, chemokine, prostaglandin and nitric oxide production (for a review, see Biro et al., 2009). Indeed, the endocannabinoid system was recently linked to reduced immune activity in many skin-inflammatory disorders (e.g. allergic contact dermatitis and skin fibrosis) (Servettaz et al., 2010).

The dual-stage hypothesis suggested herein offers a parsimonious, comprehensive, and evolutionally-sound notion, which may improve our understanding of the impact of acute and chronic stress on skin leukocyte trafficking. During stress, blood and the nutrients and oxygen supply carried in the bloodstream are known to be channeled to the skeletal muscles and brain (Joyner and Casey, 2009; MacKenzie et al., 1976) in order to facilitate immediate survival. The reduced blood flow to the skin may explain the reduction in skin leukocyte trafficking during stress. Theoretically, immediately following stress cessation, blood and leukocyte supply are restored and specifically directed to environment-immune interfaces, such as the skin and lungs, where the organism would be most susceptible to wounding and infection during the “fight or flight” stressful period. Future understanding of the exact mechanisms underlying each of the opposite processes, suggested by the dual-stage hypothesis, could potentially enable their separate effects to be harnessed to the treatment of various skin inflammatory disorders such as contact dermatitis and psoriasis, and to the treatment of skin immunosuppression-related disorders, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and diabetic gangrenes.

Research Highlight.

Rat leukocyte skin trafficking is reduced during acute or chronic stress, and increased after its cessation, without apparent involvement of epinephrine and corticosterone.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aberer E. Epidemiologic, socioeconomic and psychosocial aspects in lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1118–24. doi: 10.1177/0961203310370348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemus M, Dhabhar FS, Yang R. Immune function in PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:167–83. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham R, Benish M, Inbar S, Bartal I, Rosenne E, Ben-Eliyahu S. Synergism between immunostimulation and prevention of surgery-induced immune suppression: an approach to reduce post-operative tumor progression. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:952–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartrop RW, Luckhurst E, Lazarus L, Kiloh LG, Penny R. Depressed lymphocyte function after bereavement. Lancet. 1977;1:834–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Eliyahu S, Page GG, Yirmiya R, Shakhar G. Evidence that stress and surgical interventions promote tumor development by suppressing natural killer cell activity. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:880–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<880::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Eliyahu S, Shakhar G, Page GG, Stefanski V, Shakhar K. Suppression of NK cell activity and of resistance to metastasis by stress: a role for adrenal catecholamines and beta-adrenoceptors. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2000;8:154–64. doi: 10.1159/000054276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benish M, Bartal I, Goldfarb Y, Levi B, Avraham R, Raz A, Ben-Eliyahu S. Perioperative use of beta-blockers and COX-2 inhibitors may improve immune competence and reduce the risk of tumor metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2042–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9890-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro T, Toth BI, Hasko G, Paus R, Pacher P. The endocannabinoid system of the skin in health and disease: novel perspectives and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:411–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers SL, Bilbo SD, Dhabhar FS, Nelson RJ. Stressor-specific alterations in corticosterone and immune responses in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Zhivotovskii D, Ruderfer I, Melamed S, Botoshansky M, Tumanskii B, Apeloig Y. Nonsolvated, aggregated 1,1-dilithiosilane and the derived silyl radicals. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:739–43. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Alley PG, Booth RJ. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003:65.865–9. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088589.92699.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WH, Vujanovic NL, DeLeo AB, Olszowy MW, Herberman RB, Hiserodt JC. Monoclonal antibody to a triggering structure expressed on rat natural killer cells and adherent lymphokine-activated killer cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1989;169:1373–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Graham JE, Padgett DA, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress and wound healing. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13:337–46. doi: 10.1159/000104862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS. Stress, leukocyte trafficking, and the augmentation of skin immune function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;992:205–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection and immunopathology. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16:300–17. doi: 10.1159/000216188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS. Acute stress enhances while chronic stress suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo: a potential role for leukocyte trafficking. Brain Behav Immun. 1997;11:286–306. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress hormones on skin immune function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1059–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS, Saul AN, Daugherty C, Holmes TH, Bouley DM, Oberyszyn TM. Short-term stress enhances cellular immunity and increases early resistance to squamous cell carcinoma. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enberg R, McCullough J, Ownby D. Epinephrine-induced leukocytosis in acute asthma. Ann Allergy. 1986;57:337–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JS, Jackson JV, Rojas-Triana A, Bober LA. Evaluation of chemokine- and phlogistin-mediated leukocyte chemotaxis using an in vivo sponge model. Inflammation. 2000;24:331–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1007044914240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SB, Glasgow LA, Ader R. Differential susceptibility to a viral agent in mice housed alone or in groups. Psychosom Med. 1970;32:285–99. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendrareddy PK, Sen CK, Horan MP, Marucha PT. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates stress-impaired dermal wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguere V, Labrie F. Additive effects of epinephrine and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) on adrenocorticotropin release in rat anterior pituitary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;110:456–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore W, Moloney M, Weiner LP. The role of opioid peptides in immunomodulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;597:252–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb16174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb Y, Benish M, Rosenne E, Melamed R, Levi B, Glasner A, Ben-Eliyahu S. CpG-C oligodeoxynucleotides limit the deleterious effects of beta-adrenoceptor stimulation on NK cytotoxicity and metastatic dissemination. J Immunother. 2009;32:280.91. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31819a2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley ME, Haskell-Luevano C. The proopiomelanocortin system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;885:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haim S, Shakhar G, Rossene E, Taylor AN, Ben-Eliyahu S. Serum levels of sex hormones and corticosterone throughout 4- and 5-day estrous cycles in Fischer 344 rats and their simulation in ovariectomized females. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:1013–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03348201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski K, Pietrzak A. Indications for psychological intervention in patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:409–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce RA, Boggs DR, Hasiba U, Srodes CH. Marginal neutrophil pool size in normal subjects and neutropenic patients as measured by epinephrine infusion. J Lab Clin Med. 1976;88:614–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner MJ, Casey DP. The catecholamines strike back. What NO does not do. Circ J. 2009;73:1783–92. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, Glaser R. Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1377–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmann R. Beta-adrenergic receptors in human leukocyte subpopulations. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22(Suppl 1):30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie ET, McCulloch J, O’Kean M, Pickard JD, Harper AM. Cerebral circulation and norepinephrine: relevance of the blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol. 1976;231:483–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Van Bockstaele DR, Gastel A, Song C, Schotte C, Neels H, DeMeester I, Scharpe S, Janca A. The effects of psychological stress on leukocyte subset distribution in humans: evidence of immune activation. Neuropsychobiology. 1999;39:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000026552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL, Bachen EA, Cohen S, Rabin B, Manuck SB. Stress, immune reactivity and susceptibility to infectious disease. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:711–6. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00923-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance DM, V, Sanders M. Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987–2007) Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:736–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor R, Domankevich V, Shemer S, Sominsky L, Rosenne E, Levi B, Ben-Eliyahu S. Metastatic-promoting effects of LPS: sexual dimorphism and mediation by catecholamines and prostaglandins. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:611–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis NR, Harper C, Dafny N. Suppression of the induction of delayed hypersensitivity in rats by repetitive morphine treatments. Exp Neurol. 1986;93:92–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saul AN, Oberyszyn TM, Daugherty C, Kusewitt D, Jones S, Jewell S, Malarkey WB, Lehman A, Lemeshow S, Dhabhar FS. Chronic stress and susceptibility to skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1760–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servettaz A, Kavian N, Nicco C, Deveaux V, Chereau C, Wang A, Zimmer A, Lotersztajn S, Weill B, Batteux F. Targeting the cannabinoid pathway limits the development of fibrosis and autoimmunity in a mouse model of systemic sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:187–96. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhar G, Ben-Eliyahu S. In vivo beta-adrenergic stimulation suppresses natural killer activity and compromises resistance to tumor metastasis in rats. Journal of Immunology. 1998a;160:3251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhar G, Ben-Eliyahu S. In vivo beta-adrenergic stimulation suppresses natural killer activity and compromises resistance to tumor metastasis in rats. J Immunol. 1998b;160:3251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhar G, Blumenfeld B. Glucocorticoid involvement in suppression of NK activity following surgery in rats. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;138:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard RE, Nguyen LM. An in vivo model for evaluating wound repair and regeneration microenvironments. In Vivo. 1996;10:477–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soehnlein O, Zernecke A, Weber C. Neutrophils launch monocyte extravasation by release of granule proteins. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:198–205. doi: 10.1160/TH08-11-0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorslund K, Nordlind K. Serotonergic drugs--a possible role in the treatment of psoriasis? Drug News Perspect. 2007;20:521–5. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.8.1157614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk H, Bloksma N, Rademaker PM, Schouten WJ, Willers JM. Differential potencies of corticosterone and hydrocortisone in immune and immune-related processes in the mouse. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1979;1:285–92. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(79)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan K, Dhabhar FS. Stress-induced enhancement of leukocyte trafficking into sites of surgery or immune activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5808–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501650102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walburn J, Vedhara K, Hankins M, Rixon L, Weinman J. Psychological stress and wound healing in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:253–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WC, Jr, Ank BJ, Herbert J, Stiehm ER. Decreased bactericidal activity of leukocytes of stressed newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1975;56:579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman RJ. Stress and the adrenocortical control of epinephrine synthesis. Metabolism. 2002;51:11–4. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagron G, Weinstock M. Maternal adrenal hormone secretion mediates behavioural alterations induced by prenatal stress in male and female rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:323–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]