Abstract

The Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition study, a clinical trial aimed to prevent postnatal HIV transmission, recommended halting randomization to the enhanced standard-of-care (control) arm. The 67 mother-infant pairs on the control arm and less than 21 weeks postpartum at the time of the DSMB recommendation were read a script informing them of the DSMB decision and offering them the the maternal or infant antiretroviral interventions for the remainder of the 28-week breastfeeding period. This paper describes the BAN study response to the DSMB decision and what the women on the control arm chose, when given a choice to start the maternal or infant antiretroviral interventions.

Keywords: Postnatal HIV transmission, breastfeeding, antiretorival prophylaxis

Introduction

Breast milk transmission accounts for almost half of the estimated 420,000 HIV infections among children, annually [1]. Most of these infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa, where replacement feeding from birth is neither feasible nor safe due to cost, lack of a safe water supply, and increased risk of infant morbidity and mortality [2, 3].

Prevention of HIV transmission during breastfeeding was evaluated in the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition (BAN) study that randomized mothers and their infants to one of three study arms—with 28-weeks of postnatal antiretroviral prophylaxis given to the mother, infant, or neither [4, 5]. In March 2008, the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) overseeing the BAN study recommended halting enrollment to the control arm based on interim findings that HIV transmission was significantly reduced among infants on one of the antiretroviral intervention arms compared to the control arm. The BAN Study stopped enrollment to the control arm, and all women who were on that arm and less than 21 weeks postpartum were offered the maternal or infant antiretroviral interventions for the remainder of the 28-week breastfeeding period. Thus, the BAN Study provides a case study in how to respond to a DSMB recommendation and offers an opportunity to evaluate women’s choice regarding initiation of antiretroviral prophylaxis for prevention of postnatal HIV transmission.

Methods

At an urban healthcare facility in Lilongwe, Malawi, the BAN Study enrolled HIV-infected mothers who met prenatal and postnatal screening criteria (www.thebanstudy.org; ClinicialTrials.gov number, NCT00164736) [4, 5]. The prenatal criteria included ≥14 years of age, CD4 cell count ≥250/mm3 (≥200/mm3 before July 24, 2006), hemoglobin ≥7 g/dl, alanine aminotransaminase <2.5 times the upper limit of normal, and no serious complications of pregnancy. The postnatal criteria included infant birth weight ≥2000 g, no severe congenital malformations or other conditions incompatible with life, and no maternal condition which would preclude initiation of the antiretroviral prophylaxis. To prevent intrapartum HIV transmission, all mothers and their infants received a single dose of nevirapine at delivery, the standard of care at the time, and daily zidovudine and lamivudine for one week postpartum [6, 7]. Within 7 days of delivery, mother-infant pairs were randomized according to a factorial design to one of two nutritional study arms to prevent maternal depletion and one of three postnatal antiretroviral arms—with 28 weeks of antiretrovirals given to the mother, infant or neither—to prevent HIV transmission during breastfeeding. The maternal antiretroviral regimen was a standard triple drug regimen. The infant regimen was 28 weeks of daily nevirapine syrup with dosage increasing with age. All enrolled participants received a family maize supplement, medical care, and counseling on rapid breastfeeding cessation from 24 to 28 weeks. The mother-infant pairs were followed for up to 14 postpartum visits through 48 weeks after delivery. Infants were tested for HIV infection at birth and weeks 2, 12, 28 and 48, and those who were HIV positive were referred for care.

On March 26, 2008, an independent DSMB of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases met and reviewed interim results from the first 1,857 mother-infant pairs who had received treatment assignment. The report from this meeting stated that 1) the HIV transmission rate was significantly higher among infants on the control arm compared to infants on one of the antiretroviral intervention arms (later found to be the infant nevirapine arm) and 2) the DSMB recommended stopping enrollment to the control arm, but continuing randomization to both the antiretroviral intervention arms. The BAN study implemented the DSMB recommendations on March 27, 2008. In addition, the BAN Study team offered mothers currently on the control arm and less than 21 weeks postpartum the choice of the maternal or infant antiretroviral intervention through 28 weeks postpartum. Investigators prepared a script, in local Chichewa, explaining the DSMB recommendations (English translation shown in Appendix). The revised protocol was approved by the Malawi National Health Science Research Committee and institutional review boards at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Beginning April 14, 2008, women were read the script informing them of their choice to stay on the control arm or initiate one of the two antiretroviral interventions, and specimens were collected to determine maternal CD4 count and infant HIV status. The mothers returned one week later. Mother-infant pairs with either a maternal CD4 count <250 cells/µl or an HIV-infected infant were referred for care, but remained in study follow-up, while the remaining mother-infant pairs were offered their chosen intervention until 28-weeks postpartum or breastfeeding cessation, whichever occurred first.

Exact methods were used to determine factors associated (p<0.05) with choosing an antiretroviral intervention over remaining on the control arm in univariate logistic regression using SAS version 9.2. Maternal factors evaluated were age group, education, marital status, parity, CD4 count at screening, body mass index at 4 weeks post-partum, and occurrence of clinical or laboratory serious adverse events [5]. Infant characteristics evaluated were history of a laboratory or clinical adverse event and age in weeks and weight-for-length z-score at the time of decision.

Results

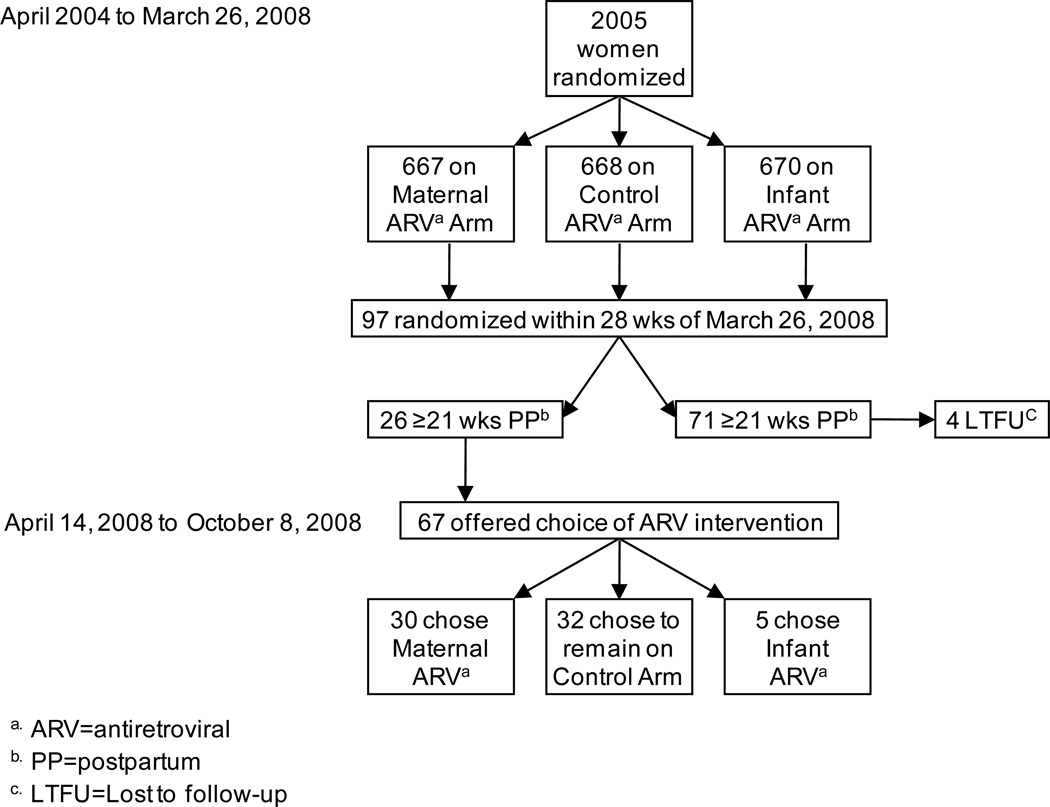

On March 26, 2008, 97 mother-infant pairs were on the control arm and within the 28-week postpartum intervention period (Figure 1). Of these, 26 were beyond 21 weeks postpartum and 4 were lost to follow-up prior to April 14, 2008. Given the choice to switch to either the maternal or infant antiretroviral intervention, about half (47.8%, n=32) chose to stay on the control arm. Mothers who chose an antiretroviral intervention (n=35) were significantly more likely to choose the maternal (85.7%) over the infant (14.3%) regimen (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Implications of halting enrollment to the control antiretroviral arm of the BAN Study.

None of the maternal factors considered were associated with choosing an antiretroviral intervention (Table 1). Although not significant, a higher proportion of the women who chose an intervention (48.6%, n=17) had more than a primary school education compared to those who chose to remain on the control arm (28.1%, n=9). Neither the mother’s CD4 count at screening nor her experience of an adverse event postpartum was associated with choosing an antiretroviral intervention.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant characteristics of mother-infant pairs who chose an antiretroviral intervention compared to those remaining on the control arm in the BAN Study.

| Number Choosing to: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start Antiretrovirals |

Remain on Control Arm |

Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | P-value a | |

| Maternal Factorsb | ||||

| Age | 0.68 | |||

| < 23 years | 14 | 10 | Ref | |

| 23 – 27 years | 9 | 11 | 0.59 (0.15, 2.26) | |

| > 27 years | 12 | 11 | 0.78 (0.21, 2.86) | |

| Marital status | 1.00 | |||

| Other | 2 | 1 | Ref | |

| Married | 33 | 31 | 0.54 (0.00, 10.80) | |

| Total number of pregnancies | 0.28 | |||

| 1 | 3 | 4 | Ref | |

| 2 | 14 | 7 | 2.57 (0.33, 22.82) | |

| 3+ | 18 | 21 | 1.14 (0.17, 8.83) | |

| Education level of mother | 0.14 | |||

| ≤ Primary education | 18 | 23 | Ref | |

| > Primary education | 17 | 9 | 2.38 (0.78, 7.63) | |

| BMI 4 weeks postpartum | 0.58 | |||

| < 21.5 kg/m2 | 10 | 10 | Ref | |

| 21.5 – 24 kg/m2 | 12 | 14 | 0.86 (0.23, 3.21) | |

| > 24 kg/m2 | 13 | 8 | 1.61 (0.40, 6.73) | |

| BMI at time of choice | 0.42 | |||

| < 21.5 kg/m2 | 10 | 11 | Ref | |

| 21.5 – 24 kg/m2 | 12 | 14 | 0.94 (0.26, 3.47) | |

| > 24 kg/m2 | 13 | 7 | 2.00 (0.49, 8.66) | |

| CD4 | 0.46 | |||

| < 400 | 11 | 12 | Ref | |

| 400 – 500 | 10 | 12 | 0.91 (0.24, 3.42) | |

| > 500 | 14 | 8 | 1.88 (0.50, 7.46) | |

| Maternal SAEc prior to choice | 0.66 | |||

| No | 33 | 29 | Ref | |

| Yes | 2 | 3 | 0.59 (0.05, 5.53) | |

| Infant Factors | ||||

| Age of infant at choice (weeks) | 0.80 (0.69, 0.90) | <0.001 | ||

| Weight-for-lengthd at choice | 2.33 (1.26, 6.64) | 0.002 | ||

| Infant SAEc prior to choice | 0.56 | |||

| No | 26 | 26 | Ref | |

| Yes | 9 | 8 | 1.49 (0.41, 5.88) | |

Odds ratios, confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values were generated by exact logistic regression with each factor as the sole covariate.

Maternal characteristics assessed at baseline (enrollment) visit unless stated otherwise.

SAE = serious adverse event.

Weight-for-height Z-Score.

The odds of a mother choosing an antiretroviral intervention decreased 20% for each week of infant age (p<0.001) (Table 1). Infant weight-for-length at the time of the choice was also associated with choosing an antiretroviral intervention (p=0.002). Mothers of infants with higher weight-for-length were more likely to choose an intervention compared to mothers of infants with lower weight-for-length (OR=2.33 for one z-score difference in weight-for-length). Age and weight-for-length remained significant in a multivariable model, adjusting each variable for the other (age p-value =0.001; weight-for-length p=0.006). Serious adverse events among infants prior to mothers choosing whether to switch to an antiretroviral intervention was not associated with the mother’s decision.

Discussion

Our study team responded swiftly to the DSMB recommendations but faced the hurdle of what to do with women already randomized to the control arm. We decided to inform the women and offer them a choice. Almost half of the mothers in the BAN study who were offered the maternal or infant antiretroviral interventions chose to remain on the control arm. Mothers were more likely to choose an intervention if they were in the earlier postpartum period, with a longer time remaining for breastfeeding and prophylaxis use. The only other independent factor associated with choosing an intervention was infant weight-for-length, which may be an indicator of general well-being of the infant and potentially their mother. Initiation of the BAN study interventions at delivery has demonstrated efficacy for prevention of HIV transmission during breastfeeding [5], but the effectiveness of these regimens when started later in the postnatal period remains unclear. Women enrolled in the BAN study were receptive to randomization to an antiretroviral intervention, and when given the choice to start an intervention, they may have intuitively chosen what makes sense scientifically: the less time remaining on the study, the lower potential benefit of the antiretroviral prophylaxis compared to the risk for side effects and resistance upon stopping.

Among mothers choosing an intervention, significantly more chose the maternal regimen. Knowledge of the benefits of antiretroviral therapy for treatment of HIV disease may have increased the motivation for the maternal regimen. Alternatively, mothers may prefer that they assume any risk of antiretroviral prophylaxis rather than their infants. To better understand mothers’ motivations, future research should ask women why they prefer one method over another.

Conclusions

Early stopping of randomization to a control arm upon evidence for clinical benefit of an intervention arm in a factorial design creates ethical and scientific difficulties as well as opportunities. Foremost, investigators must reassess the best interests of the participants on the control arm and rapidly respond accordingly. If investigators decide to offer control participants the option of study interventions, they can evaluate participant preference. The World Health Organization recently issued new guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission recommending the provision of antiretrovirals to the mother or infant during breastfeeding to prevent postnatal HIV transmission [8]. The BAN study suggests that, when given the choice of postnatal antiretroviral prophylaxis, mothers may prefer the maternal regimen.

Acknowledgements

Grant support:

The BAN study was supported by grants from the Prevention Research Centers Special Interest Project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (SIP 13-01 U48-CCU409660-09, SIP 26-04 U48-DP000059-01, and SIP 22-09 U48-DP001944-01), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID P30-AI50410), the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI50410), and the NIH Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program (DHHS/NIH/FIC 2-D43 Tw01039-06). The CDC was the primary sponsor of the study; CDC representatives were part of the study team and therefore were involved in the study design, coordination, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The study group had full access to all data in the study and had shared responsibility for the analysis and interpretation of the data and decision to submit for publication. The antiretrovirals used in the BAN study were donated by Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche Pharmaceuticals and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The manufacturers had no role in the design of the study, the collection or analysis of the data, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The Call to Action PMTCT program was supported by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation Call to Action and International Leadership Awards, UNICEF, World Food Programme, Malawi Ministry of Health, Johnson and Johnson, and USAID.

The BAN Study was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans.

The BAN Study Team:

We are grateful to the BAN Study Team at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and UNC Project team in Lilongwe including: Linda Adair, Yusuf Ahmed, Mounir Ait-Khaled, Sandra Albrecht, Shrikant Bangdiwala, Ronald Bayer, Margaret Bentley, Brian Bramson, Emily Bobrow, Nicola Boyle, Sal Butera, Charles Chasela, Charity Chavula, Joseph Chimerang’ambe, Maggie Chigwenembe, Maria Chikasema, Norah Chikhungu, David Chilongozi, Grace Chiudzu, Lenesi Chome, Anne Cole, Amanda Corbett, Amy Corneli, Ann Duerr, Henry Eliya, Sascha Ellington, Joseph Eron, Sherry Farr, Yvonne Owens Ferguson, Susan Fiscus, Shannon Galvin, Laura Guay, Chad Heilig, Irving Hoffman, Elizabeth Hooten, Mina Hosseinipour, Michael Hudgens, Stacy Hurst, Lisa Hyde, Denise Jamieson, George Joaki (deceased), David Jones, Zebrone Kacheche, Esmie Kamanga, Gift Kamanga, Coxcilly Kampani, Portia Kamthunzi, Deborah Kamwendo, Cecilia Kanyama, Angela Kashuba, Damson Kathyola, Dumbani Kayira, Peter Kazembe, Caroline C. King, Rodney Knight, Athena P. Kourtis, Robert Krysiak, Jacob Kumwenda, Edde Loeliger, Misheck Luhanga, Victor Madhlopa, Maganizo Majawa, Alice Maida, Cheryl Marcus, Francis Martinson, Navdeep Thoofer, Chrissie Matiki (deceased), Douglas Mayers, Isabel Mayuni, Marita McDonough, Joyce Meme, Ceppie Merry, Khama Mita, Chimwemwe Mkomawanthu, Gertrude Mndala, Ibrahim Mndala, Agnes Moses, Albans Msika, Wezi Msungama, Beatrice Mtimuni, Jane Muita, Noel Mumba, Bonface Musis, Charles Mwansambo, Gerald Mwapasa, Jacqueline Nkhoma, Richard Pendame, Ellen Piwoz, Byron Raines, Zane Ramdas, John Rublein, Mairin Ryan, Ian Sanne, Christopher Sellers, Diane Shugars, Dorothy Sichali, Wendy Snowden, Alice Soko, Allison Spensley, Jean-Marc Steens, Gerald Tegha, Martin Tembo, Roshan Thomas, Hsiao-Chuan Tien, Beth Tohill, Charles van der Horst, Esther Waalberg, Jeffrey Wiener, Cathy Wilfert, Patricia Wiyo, Innocent Zgambo, and Chifundo Zimba.

Finally and most especially, we thank all the women and infants that participated in the BAN study.

Abbreviations

- DSMB

Data Safety and Monitoring Board

- BAN

Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition Study

Appendix

“Dear BAN Study Participant:

Thank you for taking part in this important study. UNC Project appreciates your help. As you know, we are gathering information so we can better understand HIV infection. Part of this study is trying to find the best way to prevent your baby from getting HIV through breastfeeding. No one at present knows the best way to protect babies when the mother is infected with HIV. In BAN all mothers get one dose of Nevirapine at delivery. Also, all mothers and babies get 7 more days of HIV medicines. This is to prevent the baby from getting infected with HIV at birth and in the first 7 days of breastfeeding.

In BAN we are studying whether there are ways of preventing your baby from getting HIV. We do this by either giving HIV medicines to you or your baby or neither after the first 7 days. For the last two and a half years, an independent committee has been looking at our results on a regular basis. They are looking to see if one of those groups is doing better than the other. On March 26th 2008, they met and decided that we should no longer put mothers or infants in the group where neither receives extra medicines. Instead, they should be offered the chance to be in one of the other groups. They decided this because there is less chance of the baby getting HIV from breastmilk when either the mother or infant take medicine during breastfeeding. Women and infants who take these medicines can become sick from them. However, the benefit of taking the medicines is more than the risk of becoming sick. Please remember, babies who get the Neverapine dose at delivery with 7days of HIV medications have a smaller chance of getting HIV compared to the Malawi standard of only taking a single dose of nevirapine.

Since you were in the group that only took HIV medicines for the first 7 days, you can now choose between one of these three options:

1. You can continue to be followed on the study without you or your baby starting the new medicines. This will mean there is a small risk of your baby getting HIV through the breast milk but no side effects from the medicines.

OR

2. You can begin giving your baby nevirapine syrup until you stop breastfeeding or 28 weeks whichever comes first. There may be a smaller risk of your baby getting HIV. However, there is a small chance the medicines may not agree with your baby and may make him sick.

OR

3. You can begin taking the HIV medicines Combivir (1 tablet) and Aluvia (2 tablets). You would take these medicines each twice a day until you stop breastfeeding or 28 weeks, whichever comes first. This will mean that your baby may have a smaller chance of getting HIV. But you will have a small chance of the medicines not agreeing with you and could make you sick.

The chance of your child getting HIV depends on how long you breastfeed. It also depends on how long you will keep breastfeeding. If your child is already 24 weeks switching may not make a difference since the child would be stopping breast feeding soon anyway.

If you have understood this letter, we ask you to sign it. It states that you understand this information. Also, please circle your choice.”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Charity Chavula, Email: charitychavula2001@yahoo.co.uk.

Dustin Long, Email: dustinl@email.unc.edu.

Enalla Mzembe, Email: enallamzembe@yahoo.co.uk.

Dumbani Kayira, Email: dumbanikayira@yahoo.com.

Charles Chasela, Email: cchasela@unclilongwe.org.

Michael G. Hudgens, Email: mhudgens@bios.unc.edu.

Mina Hosseinipour, Email: mina_hosseinipour@med.unc.edu.

Caroline C. King, Email: ccking@cdc.gov.

Sascha Ellington, Email: sellington@cdc.gov.

Margret Chigwenembe, Email: mchigwenembe@unclilongwe.org.

Denise J. Jamieson, Email: djamieson@cdc.gov.

Charles van der Horst, Email: cvdh@med.unc.edu.

References

- 1.Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2009. AIDS Epidemic Update. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2000;355:451–455. [PubMed]

- 3.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. HIV and infant feeding: principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of the evidence. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Horst C, Chasela C, Ahmed Y, et al. Modifications of a large HIV prevention clinical trial to fit changing realities: a case study of the Breastfeeding, Antiretroviral, and Nutrition (BAN) protocol in Lilongwe, Malawi. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2009;30:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, Jamieson DJ, et al. Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moses A, Zimba C, Kamanga E, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission: program changes and the effect on uptake of the HIVNET 012 regimen in Malawi. AIDS. 2008;22:83–87. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f163b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farr SL, Nelson JA, Ng'ombe TJ, et al. Addition of 7 days of zidovudine plus lamivudine to peripartum single-dose nevirapine effectively reduces nevirapine resistance postpartum in HIV-infected mothers in Malawi. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2010;54:515–523. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181e3a70e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: recommendations for a public health approach. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]