Abstract

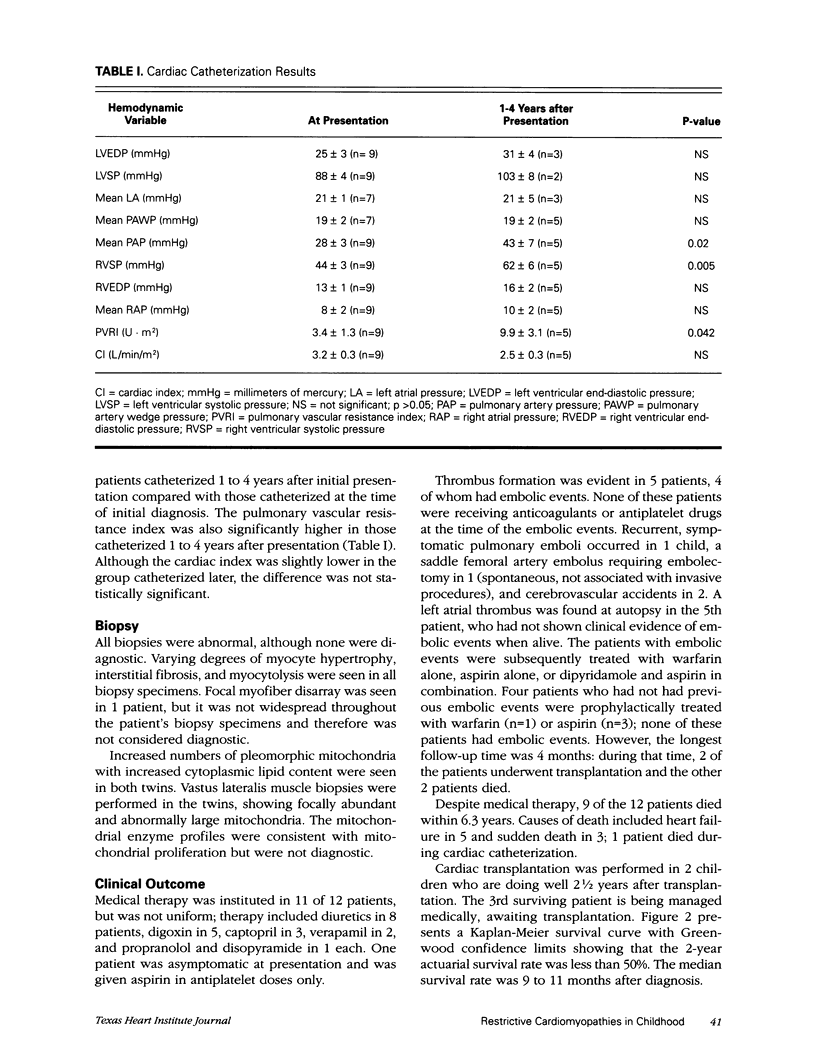

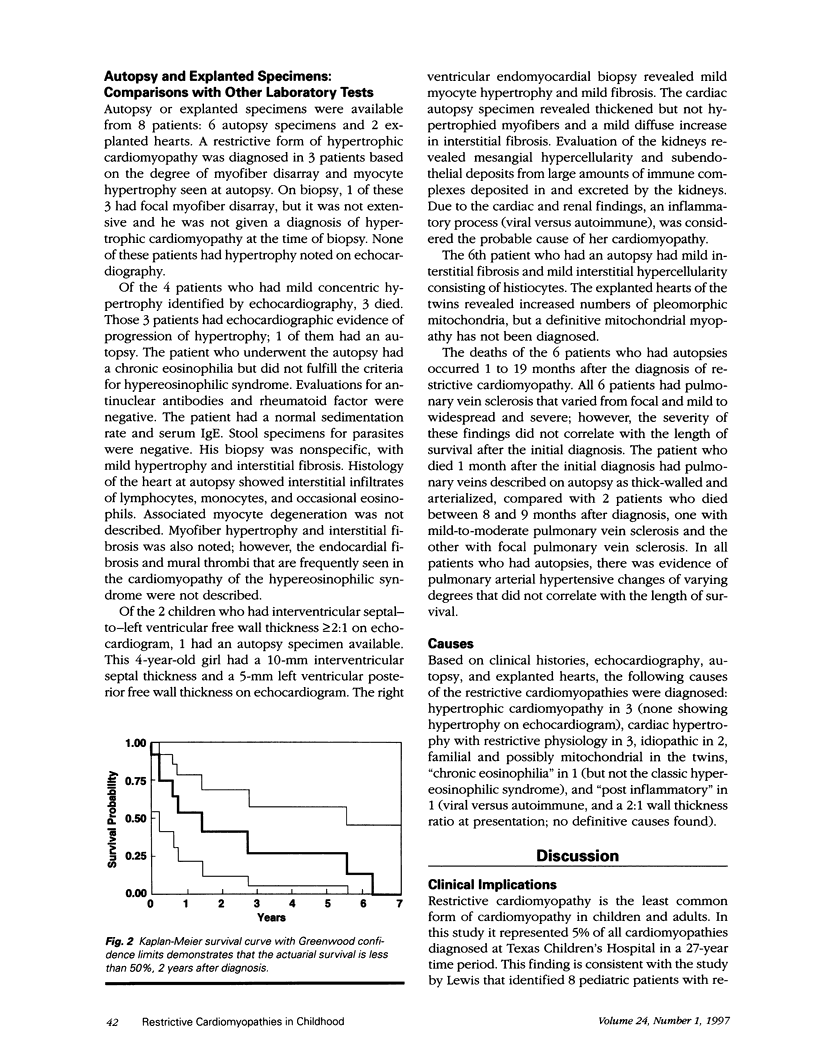

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is rare in childhood and little is known about the causes and outcome. This lack of information results in extrapolation of adult data to the care and management of children, who might require different treatment from that of adults. This study was undertaken retrospectively to evaluate the causes and natural history of restrictive cardiomyopathy in childhood. Twelve cases of restrictive cardiomyopathy were identified by database review of patient records from 1967 to 1994. The cases were selected on the basis of echocardiographic and cardiac catheterization criteria. Charts were reviewed for the following variables: age, sex, cause, right-and left-sided hemodynamics, pulmonary vascular resistance index, shortening fraction, therapy, and outcome. There were 6 males and 6 females with a mean age of 4.6 years at presentation (median, 3.4 yr; range, 0.9 to 12.3 yr). Etiologies included hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 3 patients, cardiac hypertrophy with restrictive physiology in 3, idiopathic in 2, familial in 2 (twins), "chronic eosinophilia" in 1, and "post inflammatory" with no definitive causes in 1. At presentation the mean shortening fraction was 33% +/- 2% (mean +/- SEM), average right ventricular pressures were 44/13 +/- 3/1, average left ventricular pressures were 88/25 +/- 4/3, and the mean pulmonary vascular resistance index was 3.4 +/- 1.3 U.m2 (n = 9), but increased to 9.9 +/- 3.1 U.m2 (n = 5, p = 0.04) by 1 to 4 years after diagnosis. Four of the 12 patients had embolic events (1, recurrent pulmonary emboli; 1, saddle femoral embolus; 2, cerebrovascular accidents) and 9 of 12 died within 6.3 years despite medical therapies, which included diuretics, verapamil, propranolol, digoxin, and captopril. In conclusion, restrictive cardiomyopathy in childhood is commonly idiopathic or associated with cardiac hypertrophy, and the prognosis is poor. Embolic events occurred in 33% of our patients, and 9 of 12 patients died within 6.3 years. Within 1 to 4 years of diagnosis, patients may develop a markedly elevated pulmonary vascular resistance index; therefore, transplantation should be considered early.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aroney C., Bett N., Radford D. Familial restrictive cardiomyopathy. Aust N Z J Med. 1988 Dec;18(7):877–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1988.tb01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengur A. R., Beekman R. H., Rocchini A. P., Crowley D. C., Schork M. A., Rosenthal A. Acute hemodynamic effects of captopril in children with a congestive or restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1991 Feb;83(2):523–527. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotti J. R., Grossman W., Cohn P. F. Clinical profile of restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1980 Jun;61(6):1206–1212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.6.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini E., Bosman C., Bevilacqua M., Ricci E., Gagliardi G. M., Parisi F., Servidei S., Dionisi-Vici C., Ballerini L. Cardiomyopathy and multicore myopathy with accumulation of intermediate filaments. Eur J Pediatr. 1990 Sep;149(12):856–858. doi: 10.1007/BF02072073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini E., Bosman C., Ricci E., Servidei S., Boldrini R., Sabatelli M., Salviati G. Neuromyopathy and restrictive cardiomyopathy with accumulation of intermediate filaments: a clinical, morphological and biochemical study. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;81(6):632–640. doi: 10.1007/BF00296373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetta F., O'Leary P. W., Seward J. B., Driscoll D. J. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy in childhood: diagnostic features and clinical course. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995 Jul;70(7):634–640. doi: 10.4065/70.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child J. S., Perloff J. K. The restrictive cardiomyopathies. Cardiol Clin. 1988 May;6(2):289–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick A. P., Shapiro L. M., Rickards A. F., Poole-Wilson P. A. Familial restrictive cardiomyopathy with atrioventricular block and skeletal myopathy. Br Heart J. 1990 Feb;63(2):114–118. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle L. K., Appleton C. P., Popp R. L. Differentiation of constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1989 Feb;79(2):357–370. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y., Shimizu G., Kita Y., Nakayama Y., Suwa M., Kawamura K., Nagata S., Sawayama T., Izumi T., Nakano T. Spectrum of restrictive cardiomyopathy: report of the national survey in Japan. Am Heart J. 1990 Jul;120(1):188–194. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90177-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishijima M., Kawai S., Okada R., Ino T., Yobuta K. An autopsy case of cardiomyopathy with restrictive physiology in a child. Heart Vessels Suppl. 1990;5:70–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi T., Masani F., Mitsuma S., Sasagawa Y., Kodama M., Okabe M., Tsuda T., Shibata A. Juvenile cases of restrictive cardiomyopathy without eosinophilia. Heart Vessels Suppl. 1990;5:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritsis D., Wilmshurst P. T., Wendon J. A., Davies M. J., Webb-Peploe M. M. Primary restrictive cardiomyopathy: clinical and pathologic characteristics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991 Nov 1;18(5):1230–1235. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90540-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A. L., Cohen G. I., Pietrolungo J. F., White R. D., Bailey A., Pearce G. L., Stewart W. J., Salcedo E. E. Differentiation of constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy by Doppler transesophageal echocardiographic measurements of respiratory variations in pulmonary venous flow. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Dec;22(7):1935–1943. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90782-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. B. Clinical profile and outcome of restrictive cardiomyopathy in children. Am Heart J. 1992 Jun;123(6):1589–1593. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90814-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki T., Niimura I., Nishikawa T., Sekiguchi M. An atypical case of cardiomyopathy in a child: hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy? Heart Vessels Suppl. 1990;5:84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys D., Van Coster R., Verhaaren H. Fatal outcome of pyruvate loading test in child with restrictive cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1991 Oct 19;338(8773):1020–1021. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91884-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki A., Ichida F., Suzuki Y., Okada T. Long-term follow-up of a child with idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy. Heart Vessels Suppl. 1990;5:74–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapezzi C., Ortolani P., Binetti G., Picchio F. M., Magnani B. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy in the young: report of two cases. Int J Cardiol. 1990 Nov;29(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90214-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld M. H. The differentiation of restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis. Cardiol Clin. 1990 Nov;8(4):663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. J., Shah P. K., Fishbein M. C. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1984 Aug;70(2):165–169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]