Abstract

The manualization of a complex occupational therapy intervention is a crucial step in ensuring treatment fidelity for both clinical application and research purposes. Towards this latter end, intervention manuals are essential for assuring trustworthiness and replicability of randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) that aim to provide evidence of the effectiveness of occupational therapy. In this paper, literature on the process of intervention manualization is reviewed. The prescribed steps are then illustrated through our experience in implementing the University of Southern California/Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center’s collaborative Pressure Ulcer Prevention Project (PUPP). In this research program, qualitative research provided the initial foundation for manualization of a multifaceted occupational therapy intervention designed to reduce incidence of medically serious pressure ulcers in people with SCI.

Keywords: Translational Science, Clinical Trials, Treatment Fidelity

Manualizing Occupational Therapy Interventions

As occupational therapy confronts the challenge of providing evidence-based practice, the need to design empirically based interventions capable of withstanding scientific scrutiny is increasing. Manualization of an intervention is a key step in conducting successful evaluation studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCT’s), as it enables the research team to monitor treatment fidelity, defined as the extent to which the intervention as actually delivered adheres to the program described in the research protocol (Moncher & Prinz, 1991; Lichstein, Riedel, & Grieve, 1994). If such fidelity is not established, study results may be ambiguous, incapable of future replication, or difficult to apply in other treatment contexts. Currently, most psychosocial interventions outside occupational therapy rely on manualization as the key mechanism for ensuring treatment fidelity and guaranteeing success (Chorpita, Taylor, Francis, Moffitt, & Austin, 2004; Lopata, Thomeer, Volker, Nida, and Lee, 2008; Moretti & Obsuth, 2009; Smith, et al., 2007). The significance of treatment fidelity is not well recognized within the occupational therapy field. This lack of recognition is exemplified by a literature review of 34 studies reporting on the effects of sensory integration interventions which revealed that 29 of these studies did not include measures of adherence to or quality of the intervention, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the form of the intervention under study (Parham et al., 2007).

Manuals are critical components in the effort to ensure treatment fidelity. The concept of treatment fidelity has evolved and expanded over time. Initially, treatment fidelity was conceptualized simply as treatment integrity, and merely required that the treatment be delivered as intended (Moncher & Prinz, 1991). A more recent report from the Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium recommended five areas in which fidelity could be enhanced during clinical trials: study design, training providers, delivery of treatment, receipt of treatment, and enactment of treatment skills (Bellg et al., 2004). Specific suggestions to avoid threats to fidelity (Bellg et al., 2004; Borrelli et al., 2005; Nelson & Mathiowetz, 2004) include the following: development of a treatment manual that includes information about treatment dose (length and number of contacts) and specific content of each contact; standardization of therapist training; monitoring the intervention with fidelity checklists; and inclusion of strategies to measure the subject’s comprehension and enactment of the intervention principles addressed. In this more contemporary framework, the development of a treatment manual is the first step in ensuring fidelity. The process of manualizing a treatment is the focus of this paper.

In addition to treatment fidelity, treatment manuals perform a number of other functions in both the conduct of RCT’s and within clinical practice. In particular, manuals provide structure for an intervention’s delivery, enable intervention to be delivered consistently by different therapists, facilitate staff training, and allow treatment replication in different contexts (McMurran & Duggan, 2005). Typically, manuals accomplish these aims by describing overarching treatment principles and phases, providing specific session-by-session guidelines for the intervention, specifying strategies for administering intervention content, presenting case studies that illustrate intervention principles, and detailing a plan for training therapists (Carroll & Nuro, 2002; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001; Bellg et al., 2004; Borrelli et al., 2005; Nelson & Mathiowetz, 2004).

Currently, intervention manuals are not widely used in occupational therapy clinical settings. In their place, a variety of intervention guidelines are employed, most of which are not sufficiently rigorous to be used in RCTs. For example, guides, which like manuals are documents that provide an outline of the intervention, identify the goals of the program, and describe procedures to address the goals, are less detailed and specific than manuals (Marshall, 2009). Manuals developed as structured protocols in preparation for, or as a result of, RCTs are less commonly available to practitioners, in part due to the paucity of research in the field of occupational therapy for which they would be produced and required. Thus, there is an urgent need for occupational therapy researchers and practitioners to understand the role of manualized interventions in RCTs and their subsequent use in clinical practice.

Issues Concerning Manualization of an Intervention

A key challenge in the manualization of an intervention is to provide sufficient structure and uniformity while preserving the flexibility and potential for individualization that typifies occupational therapy practice. Accordingly, the ability of manualization to allow for responsiveness to the unfolding life story of consumers as a way of prioritizing treatment goals is frequently doubted. In this paper, we address these concerns by describing (a) the advantages and disadvantages of manualization, (b) the process of development and refinement of treatment manuals, and (c) the functions of a feasibility study. Finally, to provide a concrete example, we provide a detailed description of the process of manualization used in PUPP.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Manualization

The advantages and disadvantages of manuals vary according to their purpose. The use of manuals in RCTs is considered pivotal in the success of the study, but in clinical practice they are viewed as difficult to apply and are less popular. However, the resistance towards manuals in clinical practice is unproductive because research manuals and clinical practice are mutually reliant. Intervention manuals linked to RCTs offer several advantages including the promotion of evidence-based practice, the enhancement of treatment integrity, the facilitation of staff training and quality assurance, and the potential for treatment replication (Mann, 2009; McMurran & Duggan, 2005; Wilson, 1998). In clinical practice, manuals also help clinicians focus on what is important, specify intervention procedures, delineate the theoretical rationale behind treatment, and contribute to the evolution of the intervention by explicating the reasoning process necessary to solve clinical dilemmas (Mann, 2009; McMurran & Duggan, 2005). In the psychosocial literature, studies comparing the effectiveness of manualized versus individualized treatments reveal that manualized interventions are associated with better treatment outcomes, especially when they are flexible and when the content is easily translated into action (Mann, 2009; Shapiro, Youngstrom, Youngstrom, & Marcinick, 2009; Vande Voort, Svecova, Jacobsen, & Whiteside, 2010).

However, several disadvantages of using treatment manuals have been identified. For example, typically manuals contain a single approach to intervention, which downplays the eclectic and improvisational nature of clinical practice. In this vein, manuals tend to reduce the opportunities for independent clinical judgment, and additionally can emphasize therapeutic technique and structure over process (Beutler, 1999). The use of manuals has also been reported to negatively affect the fluidity of intervention delivery and hence the quality of the interpersonal relationship between the patient and the intervener (Beutler, 1999), an important factor in the success of interventions (Elvins & Greene, 2008). For occupational therapists, whose interventions are frequently focused on the unfolding narrative of the individual (Mattingly, 1991), this can make the use of manuals particularly problematic. However, the demand for scientific legitimacy requires researchers to develop repeatable interventions. Given the pros and cons of intervention manualization, the optimal solution is to create treatment manuals that, although structured, also allow for individualization and for responsiveness to ever changing life circumstances and patient experiences that have been described as having a narrative structure.

The conflicting strengths and limitations of using manualized interventions have resulted in ambivalence among clinicians toward their use. This topic has been studied intensively in the field of psychotherapy, a discipline that shares with occupational therapy its concern that treatment manuals potentially minimize the role of clinical judgment and professional experience in shaping therapy, and where practitioners have resisted adding structure to client-based, flexible intervention practices (Beutler, 1999; Najavits, Weiss, Shaw, & Dierberger, 2000; Beutler, 2002; Chorpita, 2002; Henggeler & Schoenwald, 2002; Westen, 2002; McMurran & Duggan, 2005). On the other hand, psychotherapists have been found to value treatment manuals’ inclusion of specific techniques, descriptions of frequently encountered problems and possible solutions, clear articulation of the theoretical rationale for a treatment approach, provision of a structured approach that includes session-to-session plans, and review of empirical support for a treatment approach (Najavits, et al., 2000). To a large degree, these mixed perspectives may also be present among occupational therapists. Given the pros and cons of intervention manualization and clinicians’ ambivalence toward their use, the optimal solution may be to create manuals that, although structured, allow for individualization and for responsiveness to ever changing life circumstances and narratively described patient experiences.

Development and Refinement of Treatment Manuals

A variety of models that depict the development of treatment manuals have been described (e.g., Schnyer & Allen, 2002; Carroll & Nuro, 2002). These models differ from one another in the number of steps of manual evolution which are identified, and the list of items for inclusion. The process of developing a treatment manual for research purposes has been described from at least two different perspectives. First, Schnyer and Allen (2002) describe standardization and flexibility as a two-step process, beginning with the identification of a conceptual model and then moving to the development of a structure to enhance treatment fidelity. The establishment of a conceptual model requires taking the needs of the discipline and the populations under study into consideration. The conceptual model is based on survey of the literature, consultation with a panel of experts, and a review of existing treatment protocols. After the conceptual model is established, the next step is to develop a structure for maintaining fidelity. Fidelity structures must address the specifications of the research project, incorporate a review of previous research to identify factors that could compromise adherence, synthesize the results of prior case studies, specify evaluation tools, and attend to specific clinical issues that impact intervention delivery (Schnyer & Allen, 2002).

A second model, developed by Carrol and Nuro (2002) focuses on the connection between treatment manuals developed as part of a research project and clinicians’ subsequent application of the intervention. In this model, treatment manuals evolve through three stages. Stage I manuals are developed for feasibility and pilot studies. These preliminary manuals specify the intervention for initial evaluation, describe the problem to be addressed, indicate the intervention format and session content, explicate treatment goals, and note similarities and differences with other approaches. Stage II manuals are then developed for evaluating the efficacy of an intervention in an RCT. In addition to the content developed in Stage I, such manuals should include specific guidelines for managing clinical issues, a plan for training therapists, and attention to other aspects of treatment such as guidelines for developing patient-therapist relationships. Finally, Stage III manuals are produced for generalized use by clinicians in the field and, relative to the previous two manuals, add specifications for treating a variety of patients so that the program can be applied to diverse populations in multiple settings. For our study, we chose to follow Carroll and Nuro’s (2002) model of manual construction because it provides a comprehensive sequence of manual development which starts prior to its use in an RCT, and concludes in its delivery and application of the manual to clinical practice.

Conducting a Feasibility Study: Manual Refinement

As noted above, researchers frequently evaluate the soundness of a manualized intervention by conducting a feasibility pilot study before undertaking a full-scale RCT. Feasibility pilot studies are necessary when a planned RCT requires testing of a new intervention or procedure (Grady & Hulley, 2007; van Teijlingen & Hundley, 2001). In such studies, scaled-down versions of the proposed intervention as described in the manual are delivered to a small sample of recipients to determine the viability of intervention delivery. Other purposes of feasibility studies include assessing the success of the participant recruitment process, identifying unanticipated logistical problems, uncovering local politics that may determine the success of the intervention, and assessing costs. Even when the intervention is not novel, feasibility pilot studies can provide useful information about how the treatment plan and other aspects of the experimental protocol will play out in the actual research setting (Grady & Hulley, 2007).

The Process of Manualizing the Lifestyle Redesign® Intervention for Pressure Ulcer Prevention

The remainder of this article addresses the process of manualization as it was applied in the University of Southern California (USC)/ Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center (RLANRC) collaborative Pressure Ulcer Prevention Project (PUPP) for people with spinal cord injury (SCI). In this research program, spanning seven years and funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research and the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, a Lifestyle Redesign® Pressure Ulcer Prevention Intervention (LR-PUP) was derived from a qualitative data base and subsequently manualized. This intervention is now being investigated through a large-scale RCT for its efficacy and cost-effectiveness in reducing the incidence of medically serious pressure ulcers in adults with SCI.

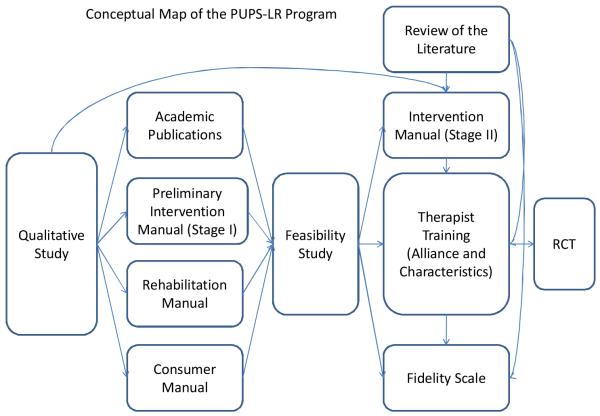

The steps that were taken to manualize LR-PUP and test its efficacy in an RCT follow a broad-based translational research blueprint that is employed at USC for developing, delivering, testing the effectiveness of, and disseminating innovative occupational therapy interventions (Clark & Lawlor, 2008; Clark et al., 1997; Jackson et al., 1998). Figure 1 depicts how the blueprint was utilized for the manualization and effectiveness testing of the LR-PUP. First, a three-year ethnographic (qualitative) study of 20 adults with SCI and a history of recurring pressure ulcers was undertaken. Through in-depth interviews and participant observations, detailed information was gathered on the everyday life circumstances that contribute to the formation of pressure ulcers in adults with SCI (Clark et al., 2006; Jackson et al., 2010). In addition to generating academic publications (Clark et al., 2006; Fogelberg, Atkins, Blanche, Carlson, & Clark, 2009; Jackson et al., 2010; Seip, Carlson, Jackson, & Clark, 2010), this qualitative study yielded several intervention-related products, including a, Stage I intervention manual (USC-RLANRC PUPP, 2005), a manual for rehabilitation professionals (USC-RLANRC PUPP, 2006a), and an on-line consumer manual (USC-RLANRC PUPP, 2006b).

FIGURE 1.

SEQUENTIAL STEPS TAKEN IN THE PUPP-LIFESTYLE REDESIGN® RESEARCH PROGRAM

As depicted in the center of Figure 1, these products were used to guide the design and implementation of a feasibility study, in which the utility and soundness of the intervention was pilot tested. The feasibility study, in turn, led to an expanded literature search, the development of the Stage II LR-PUP intervention manual, a corresponding therapist intervention training program, and the construction of a fidelity scale, the last three of which are now being employed in the on-going PUPP RCT.

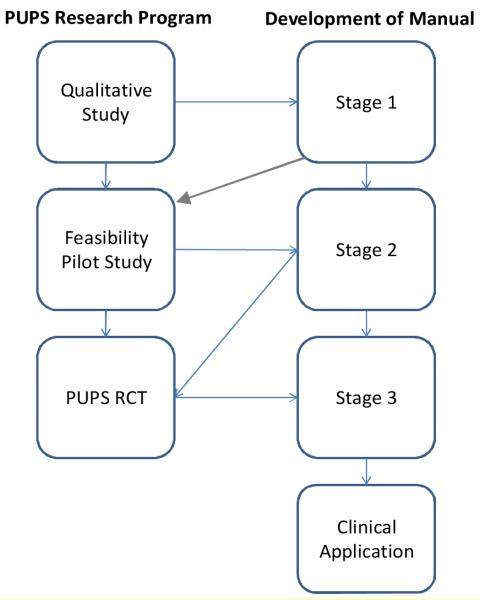

The development of the PUPP Lifestyle Redesign® Manual was consistent with Carroll and Nuro’s (2002) three stage model described above. The chronological relationship between the steps of the translational science process and the stages of manual development is depicted in Figure 2. The Stage II manual is currently being employed in the ongoing PUPP RCT. Following completion of the RCT, a Stage III manual will be produced for use in clinical settings.

FIGURE 2.

DEVELOPMENT OF MANUALS IN PUPP-LIFESTYLE REDESIGN® PROGRAM

Development of the Stage I Manual

The Stage I manual (USC-RLANRC PUPP, 2005) was constructed based on two core sources. First, it broadly followed the general treatment approach that had been successfully applied in the USC Well Elderly Study (Clark et al., 1997) to promote positive health outcomes in older adults. The basic principles of that Lifestyle Redesign® program included eight elements that were embedded in the LR-PUP intervention: (1) significance of the therapist-client relationship; (2) client-centeredness; (3) emphasis on social support; (4) application of health-related knowledge; (5) use of resources; (6) focus on daily life activities in multiple settings; (7) attention to existing, anticipated, or unanticipated life circumstances that impact risk; and (8) individualization (Clark, 1993; Clark et al., 1997; Clark et al.,2001; Jackson, Carlson, Mandel, Zemke, & Clark, 1998; Mandel, Jackson, & Clark, 1999).

Second, the Stage I manual incorporated provisional topics for emphasis that had been identified during the PUPP ethnographic study, each of which described a factor (e.g., smoking, attendant care, self-advocacy) that was found to either directly or indirectly affect the participants’ pressure ulcer risk. Accordingly, the Stage I manual was subdivided into the following 14 units: Occupational Storytelling and Occupational Story Making, Pressure Ulcer Knowledge, Self Advocacy, Attendant Care, Changing Body, Environment and Adaptive Equipment, Habits and Routines, Chronic Pain, Participation and Activity, Depression and Other Mental Health Issues, Social Support, Transportation, Spirituality, and Wrap Up Session. Each unit provided a description of the topic, noted suggested treatment activities, provided tips for therapists, and listed additional resources for both interveners and participants. This early rendition of the LR-PUP manual was compiled by an occupational therapy doctoral student, and subsequently tested for its feasibility in the pilot study described next.

The PUPP feasibility study

The feasibility study, conducted in preparation for the PUPP RCT, had four aims: (a) to provide preliminary information about issues surrounding RCT methodology with the targeted population (e.g., strategies for recruitment), (b) to determine the viability of the basic intervention design, (c) to refine the initial Stage I intervention manual, and (d) to pinpoint the steps required to maintain the fidelity of the intervention. For the feasibility study, six participants (five men and one woman) were recruited from a surgical unit specializing in the treatment of pressure ulcers.

Findings of this study suggested that the intervention was in fact viable and potentially helpful in preventing pressure ulcers. In addition, the findings indicated that the intervention could be administered to consumers of different racial and ethnic backgrounds and that principles of Lifestyle Redesign® were readily translatable into the individualized treatment session format. However, in its existing form the manual was unwieldy and cumbersome to use. The modules in the stage 1 manual did not provide enough flexibility for the interveners and the manual did not provide a detailed structure for each therapeutic encounter. Because the manual failed to provide sufficient flexibility and structure, the interveners felt compelled to choose between a mechanized intervention and relying on their own clinical background to establish a therapeutic relationship, and thus did not follow the units described in the manual. Based on these results, the content was reorganized into six major units which will be described later in this paper.

The LR-PUPP Stage II Manual

The Stage II manual was completed prior to implementing the PUPP RCT, and is currently being used to guide intervention delivery in the trial. This revised version incorporates more refined descriptions and details of both the content and process dimensions of the intervention.

Content

The Stage II manual was an improved version of the Stage I manual because it incorporated modifications based on: (a) the most current literature on risk factors and proximal causes of pressure ulcer development (Clark et al., 2006; Rodriguez & Garber, 1994); and (b) additional analyses of the data that had been generated during the PUPP ethnographic study. The latter had resulted in the development of a series of models depicting the process through which various risk factors interacted in complex ways in the context of individuals’ everyday lives to eventuate in pressure ulcers (Clark et al., 2006) and the identification of seven overarching principles that accounted for pressure ulcer development in people with SCI (Jackson et al., 2010). Not only were the models and principles incorporated into the manual’s modularized units, but they also spurred the generation of new worksheets and treatment activities to be performed during the intervention sessions. For example, following the presentation of the theoretical model emphasizing consideration of the balance between buffers and liabilities (Clark et al., 2006), detailed clinical reasoning worksheets were included to facilitate the therapeutic problem solving process related to this concern.

Process

In contrast to the Stage I manual, the Stage II manual combined two intervention approaches and was developed by a team of researchers and clinicians. The first approach, which as noted earlier was included in the Stage I manual, entailed comprehensive principles of Lifestyle Redesign® applied to pressure ulcer prevention to adults with SCI (Clark et al., 1997; Clark et al., 2006; Jackson et al., 2010). In addition, the techniques of Motivational Interviewing, a therapist-client collaborative approach responsive to the participant’s stage of readiness-to-change (Rollnick, Mason & Butler, 1999; Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008), was enfolded into the intervention guidelines in the Stage II manual. The inclusion of a team of researchers and clinicians in the development of the Stage II manual guaranteed that the manual answered to clinicians’ need for flexibility as well as individualization. To address these concerns, the manual was refined so that (a) the order of the modules could be altered on a case-by-case basis, (b) each module included fixed and variable (optional, to be addressed only if relevant to a particular consumer) topics, and (c) the use of the manual could be shaped by the content of the participants unfolding life story or narrative experience as it pertained to pressure ulcer risk. For example, for one participant the equipment module might consist of identifying funding sources such as private grants and foundations to purchase appropriate equipment while for another participant it might involve exploring the participant’s reasons for non-utilization of currently owned working equipment.

In the final rendition of the Stage II manual, modules were expanded and reorganized into six thematic units to be delivered during the first six months of the one year intervention. In addition, a tapering phase during which intervener support is gradually reduced was specified for the intervention’s final six months. The six main topics addressed in the manual, include: Understanding Pressure Ulcer Risk, Taking Charge (advocacy), Assessing the Physical Environment, Social Networks and Meaningful Relationships, Happiness and Personal Well-being, and Planning the Future. Each unit is divided into four in-person or phone contacts, with each contact including both fixed and variable themes. With the exception of the first and the last module, the topical content is flexible in that it can be used in any order according to each participant’s needs and unfolding life story in relation to threats to skin integrity. Within the manual, specifications are presented for each contact including an introduction, an outline of goals, suggested activities, a list of resources for the intervener, articulation of areas for further exploration, references, and forms that can be used to expedite problem solving in response to emergent threats and concerns. Table 1 presents the differences between the Stage I and Stage II manual.

Table 1. Comparison between Stage I and II Manuals.

| AREAS ADDRESSED Based on the criteria of Carroll and Nuro (2002). |

STAGE I (Feasibility Pilot) |

STAGE II (RCTs) |

|---|---|---|

| Overview of the intervention |

Included | Included |

| The disorder, assessment tools, and therapeutic strategies. |

|

|

| Specification and prioritization of treatment goals, and strategies for identifying and negotiating patient’s goals |

|

|

| Session-by-session content of the intervention with examples |

|

|

| Contrast, similarities and compatibility with other treatment approaches |

|

|

| Elaborated rationale and empirical data from pilot study and other studies |

|

|

| Selection and training of therapists |

|

|

| Preparation for Stage III Manual: transportability to the clinical community and addressing diversity |

|

|

The Stage II manual also contains elements to counteract three specific disadvantages of manualization described in the literature: use of a single approach that does not reflect the eclectic and improvisational nature of clinical practice; diminished intervention fluidity; and a reduction in the effectiveness and “art” of therapy of experienced practitioners (Beutler, 1999; McMurran & Duggan, 2005; Westen, 2002). For example, it redresses the concern with balancing structure, flexibility, and individualization by incorporating more than one intervention approach to (i.e., both Lifestyle Redesign® and Motivational Interviewing), encouraging clinicians to rely upon their own clinical reasoning when flexibility is required, directing interveners to utilize overarching theoretical principles and models laid out in the manual, and allowing clinicians to tailor the content of modules in response to the emerging threats to skin integrity.

Illustrating the flexibility of the overall treatment approach, the LR-PUP manual can be used to address the risk-relevant happenstances that unfold within the consumer’s life. For example, one participant recently decided to temporarily move to another state. His travelling arrangements required him to lay down in the back of a van for several hours, a situation that heightened his risk for the formation of pressure ulcers. Although the LR-PUP manual does not explicitly include specific content on how to avoid ulcers during the process of moving, it does contain information on how to prevent ulcer development during short car rides. In this case, the intervener used the opportunity to cover the relevant manual content, modifying it in response to this participant’s unique life situation. Beyond this application, the intervener also had to rework manual content so that it could be effectively delivered by phone contact during the period in which the participant would be away.

As the PUPP RCT progresses, additional revisions will be recommended that will be incorporated into a Stage III manual prior to its dissemination into the community for widespread use. It is anticipated that this manual should be sufficiently refined to enhance treatment integrity, facilitate staff training, promote quality assurance, and increase the potential for replication of the intervention (Wilson, 1998; McMurran & Duggan, 2005).

Conclusion

The current emphasis on evidence-based practice, in conjunction with the requirements of RCTs, creates the need for manualized interventions as part of the process of establishing intervention fidelity. However, to date only a sparse number of manualized occupational therapy interventions exist (Nelson & Mathiowetz, 2004). One reason for this paucity is the continuing challenge for occupational therapy researchers to reconcile the client-centered and individualized nature of practice with the need to manualize interventions. Our experience in the PUPP research program has revealed that occupational therapy treatment manuals need not be rigid or constrain therapists’ clinical reasoning, as the second version of the LR-PUPP manual allows for individualization and flexibility within the context of an overarching structure, explicit guiding principles, and theoretical models (Vaishampayan, Clark, Carlson, & Blanche, 2010). In its second stage, the LR-PUP manual has the following desirable components: (a) it combines two primary theoretical models, Lifestyle Redesign® and Motivational Interviewing; (b) its structure reflects a menu from which interveners can select topics based on the consumer’s needs; (c) it mandates common training and weekly supervision sessions in which to share successful strategies; (d) it allows for the intervention to be anchored in the ongoing narrative experience of consumers, and (e) its overarching principles and content provide sufficient structure to enable replication for an RCT.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research, USC Department of Education (grant no. H133G000062). The project was also supported by Award Number R01HD05267 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. The authors also thank Mary Kay Wolf, OTD, OTR/L and Faryl Saliman Rheingold OTD, OTR/L for their work on the intervention manual. We acknowledge the contributions of the participants who have been enrolled in the PUPP studies and the support and effort of numerous other individuals, especially the LR-PUPP intervention team.

References

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE. Manualizing flexibility: The training of eclectic therapists. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55:399–404. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199904)55:4<399::aid-jclp4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE. It isn’t the size, but the fit. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2002;9:434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Sepinwall D, Ernst D, Bellg AJ, Czajkowski S, Breger R, Orwig D. A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:852–860. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nuro KF. One size cannot fit all: A stage model for psychotherapy manual development. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2002;9:396–406. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollindick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF. Treatment manuals for the real world: Where do we build them? Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2002;9:431–433. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Taylor AA, Francis SE, Moffitt CE, Austin AA. Efficacy of modular cognitive behavior therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Clark F, Azen SP, Zemke R, Jackson J, Carlson M, Mandel D, Lipson L. Occupational therapy for independent-living older adults: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:1321–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark F, Lawlor M. The making and mattering of occupational science. In: Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Boyt BA, editors. Willard and Spackman’s Occupational Therapy. 11th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Clark F, Jackson JM, Scott MD, Carlson ME, Atkins MS, Uhles-Tanaka D, Rubayi S. Data-based models of how pressure ulcers develop in daily-living contexts of adults with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;87:1516–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvins R, Green J. The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: An empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1167–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogelberg D, Atkins M, Blanche EI, Carlson M, Clark F. Decisions and dilemmas in everyday life: Daily use of wheelchairs by individuals with spinal cord injury and the impact on pressure ulcer risk. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 2009;15(2):16–32. doi: 10.1310/sci1502-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady D, Hulley SB. Implementing the Study and Quality Control. In: Hulley Stephen B., Cummings Steven R., Browner Warren S., Grady Deborah G., Newman Thomas B., editors. Designing Clinical Research. 3rd Edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK. Treatment manuals: Necessary, but far from sufficient. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2002;9:419–420. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Carlson M, Mandel D, Zemke R, Clark F. Occupation in lifestyle redesign: The well elderly study occupational therapy program. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;52:326–336. doi: 10.5014/ajot.52.5.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Carlson M, Rubayi S, Scott M, Atkins M, Blanche E, Clark F. Qualitative study of principles pertaining to lifestyle and pressure ulcer risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2010;32:567–578. doi: 10.3109/09638280903183829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichstein KL, Riedel BW, Grieve R. Fair tests of clinical trials: A treatment implementation model. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1994;16:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lopata C, Thomeer ML, Volker MA, Nida RE, Lee GK. Effectiveness of a manualized summer social treatment program for high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(5):890–904. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE. Sex offender treatment: The case for manualization. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2009;15(2):121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WL. Manualization: A blessing or a curse? Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2009;15(2):109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly C. The narrative nature of clinical reasoning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45:998–1005. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.11.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti MM, Obsuth I. Effectiveness of an attachment-focus manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive behaviour: The Connect Program. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(6):1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurran M, Duggan C. The manualization of a treatment programme for personality disorder. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2005;15:17–27. doi: 10.1002/cbm.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncher FJ, Prinz RJ. Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991;11:247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR, Dierberger AE. Psychotherapists’ views of treatment manuals. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice. 2000;31:404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DL, Mathiowetz V. Randomized controlled trials to investigate occupational therapy research questions. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;58:24–34. doi: 10.5014/ajot.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham LD, Cohn ES, Spitzer S, Koomar JA, Miller LJ, Burke JP, Summers CA. Fidelity in sensory integration intervention research. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61:216–227. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez GP, Graber SL. Prospective study of pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury patients. Paraplegia. 1994;32:150–158. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. Churchill Livingstone. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior (applications of Motivational Interviewing) Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schnyer RN, Allen JJ. Bridging the gap in complementary and alternative medicine research: Manualization as a means of promoting standardization and flexibility of treatment in clinical trials of acupuncture. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(5):623–634. doi: 10.1089/107555302320825147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip J, Carlson M, Jackson J, Clark F. Pressure ulcer risk assessment in adults with spinal cord injury: The need to incorporate daily lifestyle concerns. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JP, Youngstrom JK, Youngstrom EA, Marcinick HF. A comparison of the effectiveness of manualized and naturally occurring therapy for children with disruptive behavior disorders. New Research in Mental Health. 2009;I:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Scahill L, Dawson G, Guthrie D, Lord C, Odom S, Wagner A. Designing research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(2):354–366. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USC-RLANRC Pressure Ulcer Prevention Project . A Lifestyle Redesign Occupational Therapy Pressure Ulcer Prevention Program. University of Southern California; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- USC-RLANRC Pressure Ulcer Prevention Project . Rehabilitation professional’s manual. University of Southern California; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- USC-RLANRC Pressure Ulcer Prevention Project Pressure ulcer prevention project. 2006b Retrieved from http://www.usc.edu/programs/pups/

- Vaishampayan A, Clark F, Carlson M, Blanche EI. Individualization of a manualized pressure ulcer prevention program: targeting risky life circumstances through a community-based intervention for people with spinal cord injury. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- van Teijlingen ER, Hundley V. The importance of pilot studies. Nursing Standard. 2002;16(40):33–36. doi: 10.7748/ns2002.06.16.40.33.c3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Voort JL, Svecova J, Jacobsen AB, Whiteside SP. A retrospective examination of the similarity between clinical practice and manualized treatment for childhood anxiety disorders. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17:322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Westen D. Manualizing manual development. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2002;9:416–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Manual-based treatment and clinical practice. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 1998;5:363–375. [Google Scholar]