Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Endoscopic ablation of Barrett's esophagus can bury metaplastic glands under a layer of neosquamous epithelium. To explore the frequency and importance of buried metaplasia, we have conducted a systematic review of reports on endoscopic ablation.

METHODS

We performed computerized and manual searches for articles on the results of photodynamic therapy (PDT) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for Barrett's esophagus. We extracted information on the number of patients treated, biopsy protocol, biopsy depth, and frequency of buried metaplasia.

RESULTS

We found 9 articles describing 34 patients with neoplasia appearing in buried metaplasia (31 after PDT). We found five articles describing a baseline prevalence of buried metaplasia (before ablation) ranging from 0% to 28% . In 22 reports on PDT for 953 patients, buried metaplasia was found in 135 (14.2%); in 18 reports on RFA for 1,004 patients, buried metaplasia was found in only 9 (0.9%). A major problem limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from these reports is that they do not describe specifically how frequently biopsy specimens contained sufficient subepithelial lamina propria to be informative for buried metaplasia.

CONCLUSIONS

Endoscopic ablation can bury metaplastic glands with neoplastic potential but, even without ablation, buried metaplasia often is found in areas where Barrett's epithelium abuts squamous epithelium. Buried metaplasia is reported less frequently after RFA than after PDT. However, available reports do not provide crucial information on the adequacy of biopsy specimens and, therefore, the frequency and importance of buried metaplasia after endoscopic ablation remain unclear.

INTRODUCTION

Barrett's esophagus is the condition in which metaplastic columnar epithelium that predisposes to cancer development replaces the stratified squamous epithelium that normally lines the distal esophagus (1). The condition is a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, a tumor whose incidence has increased by more than sixfold over the past several decades in the United States (2). Endoscopic ablation has been proposed as a way to prevent cancer from developing in Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopic ablative therapies use thermal or photochemical energy to destroy the metaplastic epithelium that gives rise to the tumors (1). After the procedure, patients are treated with proton pump inhibitors to control acid reflux, which enables the ablated columnar epithelium to heal with new (neo)squamous epithelium.

A number of different endoscopic ablative modalities have been described, but recent attention has focused primarily on photo-dynamic therapy (PDT) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). For PDT, patients are given a systemic dose of a light-activated chemical (e.g., porfimer sodium) that is taken up by the metaplastic esophageal epithelium, which is then irradiated with laser light (3). The chemical transfers its laser-acquired energy to molecular oxygen to produce singlet oxygen, a toxic molecule that attacks vital cellular structures and causes cell death through necrosis and apoptosis. RFA uses endoscopic guidance to position a balloon with a circumferential array of electrodes to deliver radiofrequency energy to the metaplastic esophageal mucosa (4). Using a generator to control the power, density and duration of the radiofrequency energy applied, RFA was designed to inflict a uniform, circumferential thermal injury of limited depth. Using PDT or RFA, it is relatively easy to ablate long segments of metaplastic epithelium, and both techniques have been shown to prevent progression from dysplasia to cancer in randomized, controlled trials.

If an ablation procedure does not destroy all of the metaplastic epithelium, then the partially ablated mucosa may heal with an overlying layer of neosquamous epithelium that buries metaplastic glands in the lamina propria where they are hidden from the endoscopist's view. This “buried metaplasia” may have malignant potential. In fact, there are reported cases of cancer appearing in buried metaplastic glands (5,6). However, the frequency with which endoscopic ablation results in buried metaplasia is not clear, and the importance of this condition is disputed. We have conducted a systematic review of the literature on Barrett's esophagus to answer the following questions: (i) What is the frequency of buried metaplasia after PDT? (ii) What is the frequency of buried metaplasia after RFA? (iii) What is the baseline frequency of buried metaplasia (i.e., the frequency of buried metaplasia in Barrett's patients who have not had endoscopic ablation procedures)? (iv) What is the frequency of neoplasia in buried metaplasia?

METHODS

Search strategy

We followed the PRISMA recommendations for systematic literature analysis (7). Two members of the study team (NAG and SJS) searched the PubMed search engine of MEDLINE-indexed literature from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.pubmed.gov), as well as the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) for English language articles published through April 2011. We performed additional searches of MEDLINE using the Ovid database, including Ovid MEDLINE 1948 to present and Ovid MEDLINE (R) In-process and other Non-indexed Citations.

To identify relevant articles for questions (i) and (ii) (the frequency of buried metaplasia after PDT and RFA), we used the medical subject heading search term “Barrett esophagus” (also “Barrett's esophagus,” “Barrett oesophagus,” or “Barrett's oesophagus”) combined with the keywords “photodynamic therapy,” “photodynamic ablation,” “PDT,” “radiofrequency ablation,” and “circumferential ablation.” To identify relevant articles for questions (iii) and (iv) (the frequency of buried metaplasia at baseline and the frequency of neoplasia in buried metaplasia), we used the same medical subject heading terms as above combined with the keywords “buried glands,” “buried Barrett's,” “buried metaplasia,” “buried cancer,” buried neoplasia” and “subsquamous glands,” “subsquamous Barrett's,” “subsquamous metaplasia,” subsquamous cancer,” and “subsquamous neoplasia.” We screened each abstract resulting from these searches for eligibility. Additionally, we searched the reference lists of each article selected for inclusion to identify additional articles meeting eligibility requirements. This process was performed independently by the reviewers and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus after discussion among the authors.

Study selection

Study selection criteria were determined a priori. For articles on post-ablative buried metaplasia (questions (i) and (ii)), we used the following inclusion criteria: (i) the reports described data (prospective or retrospective) on the use of PDT (porfimer sodium or 5-ALA) or RFA for Barrett's esophagus; (ii) series included at least five patients; (iii) study patients had at least one follow-up endoscopy that included esophageal biopsy sampling after endoscopic ablation; and (iv) results specifically described the frequency of buried metaplasia following the endoscopic treatment. We excluded review articles, editorials and letters to the editor, and we excluded reports of studies if (i) techniques of endoscopic ablation other than PDT or RFA were used; (ii) data on esophageal biopsy sampling were not described; (iii) the report specified that all study patients had been included in previously published series; (iv) the reports focused on secondary analyses of patients who had been included in previously published reports. For articles on baseline buried metaplasia (question (iii)), we used the following inclusion criteria: (i) esophageal biopsy samples were taken before any form of endoscopic therapy and (ii) histological analyses of esophageal biopsy specimens included a description of the finding of buried metaplasia. Reports of neoplasia in buried metaplasia (question (iv)) were included if they described neoplasia found in glands located beneath esophageal squamous epithelium at any time during follow-up of patients who had any form of endoscopic ablative therapy.

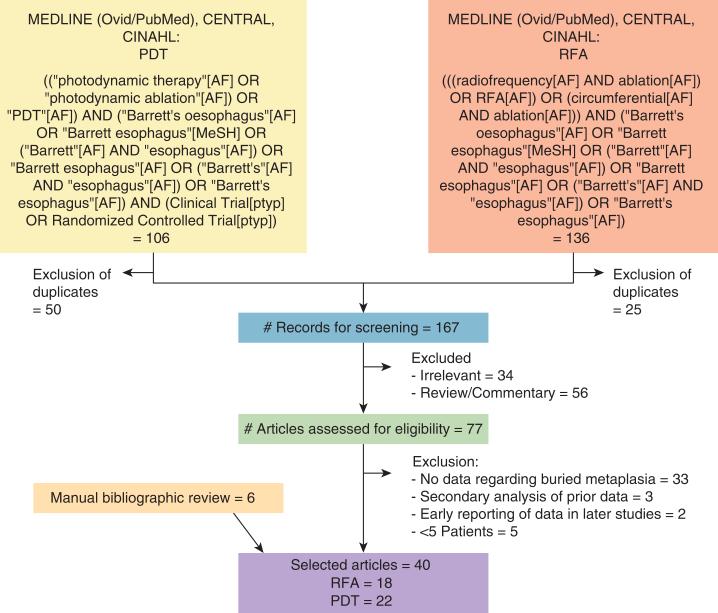

A flow chart summarizing the literature search is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search. AF, all searchable fields; MeSH, medical subject heading; PDT, photodynamic therapy; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Data abstraction

For reports on the frequency of buried metaplasia after ablative therapy, variables assessed in the data abstraction process included number of patients treated, baseline degree of dysplasia, number of esophageal biopsies obtained, surveillance protocol used, system used to assess biopsy depth, duration of follow-up, and number of patients found to have buried metaplasia. Data extracted from reports of baseline buried metaplasia included number of patients, frequency of baseline buried metaplasia, and degree of neoplasia detected. Data extracted from reports of buried neoplasia included patient's age, type of endoscopic therapy used, baseline degree of neoplasia (before treatment), time after ablation to detection of buried neoplasia, and outcome data.

RESULTS

Reports of neoplasia in buried metaplasia

Two case reports have been cited frequently as evidence that adenocarcinoma can arise from buried metaplasia (5,6). In addition, we found seven reports on endoscopic ablative therapy that provided information on neoplasia (including low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia (HGD), intramucosal carcinoma, and invasive adenocarcinoma) in buried metaplasia (8–14). Table 1 summarizes these 9 articles, which include a total of 34 patients who had endoscopic ablation and were subsequently found to have low-grade dysplasia (1 patient), HGD (13 patients), intramucosal carcinoma (11 patients), or invasive adenocarcinoma (6 patients) detected under squamous epithelium during follow-up intervals ranging from 4 to 52 months (in three cases, the degree of buried neoplasia was not reported). Th irty-one of the thirty-four cases occurred after PDT (8–12,14) whereas three occurred after argon plasma coagulation or laser ablation (5,6,13). We did not identify any reports of neoplastic glands situated beneath squamous epithelium after RFA. Two cases of buried neoplasia were reported to be detected because of associated endoscopic abnormalities (5,6); for the other cases, generally insufficient information was provided to determine whether biopsy specimens were obtained from visible lesions or flat mucosa, or if residual metaplastic mucosa was present.

Table 1.

Published cases of neoplasia in buried metaplasia

| Report first author | Patient age (years) | Endoscopic therapy | Baseline degree of neoplasia | Location of buried neoplasia | Degree of buried neoplasia | Time after ablation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shand et al. (5) | 67 | APC | LGD | NR | Metastases (liver) | 4 months | Unresectable tumor |

| Van Laethem et al. (6) | 68 | APC | No dysplasia | Squamo-columnar junction | TisN0 | 18 months | EMR, no recurrence at 12 months |

| Mino-Kenudson et al. (8) | NR | PDT | HGD/superficial adenocarcinoma | Variable | IA (2) IMC (4) HGD (6) LGD (1) |

2–25 months | 8 of 13 responded to another session of endoscopic therapy |

| Overholt et al. (9) | NR | PDT | HGD | Near NSQ-columnar junction in 2 of 3 patients | NR | 6 months, 46 months, 52 months | 1—retreated, no recurrence at 3 years 1—retreated, no recurrence at 1 year 1—brachytherapy, local recurrence at 6 months |

| Ban et al. (10) | NR | PDT | HGD/superficial adenocarcinoma | NR | IA—3 IMC—2 HGD—7 |

NR | NR |

| Ragunath et al. (11) | 55 | PDT | LGD | NR | T1N0 | 4 months | Esophagectomy |

| Overholt et al. (12) | NR | PDT | HGD | Center of treated area | IMC | 6 months | Repeat PDT; no recurrence at 24 months |

| Bonavina et al. (13) | NR | Laser ablation | No dysplasia | NR | T1N0 | 6 months | Esophagectomy |

| Wolfsen et al. (14) | NR | PDT | T1N0M0 adenocarcinoma | At site of prior lesion | T1N0 | NR | Esophagectomy |

APC, argon plasma coagulation; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IA, invasive adenocarcinoma; IMC, intramucosal carcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; NR, not reported; NSQ, neosquamous; PDT, photodynamic therapy.

The reports generally do not describe long-term patient outcomes, but there is at least one description of a patient who had incurable, metastatic cancer associated with buried adenocarcinoma (5). In the majority of cases, buried neoplasia was detected within 18 months of ablation. Therefore, it is not clear whether the neoplasms developed from non-neoplastic glands that were buried by the ablation, or from neoplastic glands that either were already subsquamous before ablation or that were buried by the ablation procedure.

Frequency of buried metaplasia at baseline (before PDT or RFA)

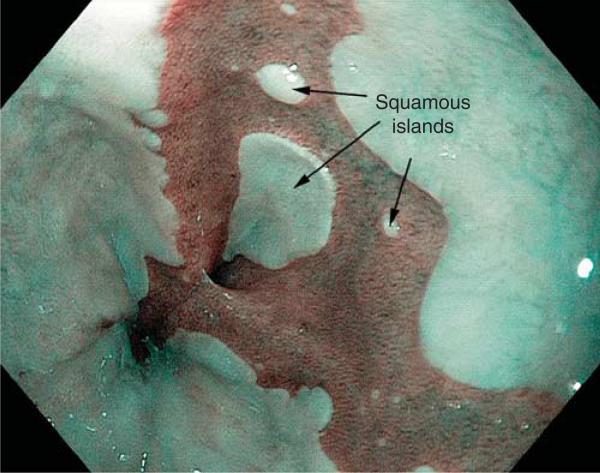

Buried metaplasia has been described in patients with Barrett's esophagus who have not had endoscopic ablation (15). It is possible that metaplastic glands grow underneath squamous epithelium spontaneously at squamo-columnar junction areas. It also has been proposed that, as a consequence of extensive biopsy sampling of metaplastic epithelium during endoscopic surveillance, the esophageal biopsy sites heal via growth of neosquamous epithelium that buries metaplastic glands (15,16). Biopsy-induced regrowth of squamous epithelium is presumed to be the origin of “squamous islands” that are found frequently in Barrett's esophagus during endoscopic surveillance (Figure 2). In one study of Barrett's patients who had not received ablation therapy, biopsy specimens of squamous islands revealed buried metaplasia in 38.5% of cases (17).

Figure 2.

Endoscopic photograph of Barrett's esophagus using narrow band imaging. The metaplastic columnar (Barrett's) epithelium is dark, and the squamous epithelium is light. Notice the squamous islands, which presumably develop as a consequence of biopsy sampling of metaplastic epithelium during endoscopic surveillance.

We identified five reports that described the prevalence of buried metaplasia at baseline in patients who subsequently had PDT or RFA (Table 2) (8,10,15,18,19). The baseline prevalences ranged from 0% to 28% . The highest baseline prevalence rate (28%) was found in a study that examined endoscopic mucosal resection specimens (which usually include submucosal tissue) from patients who had HGD or intramucosal carcinoma (19). The other studies examined endoscopic pinch biopsy specimens, which infrequently include submucosa, and none of the reports provided specific information on the depth of the pinch biopsy specimens evaluated.

Table 2.

Frequency of buried metaplasia at baseline (before endoscopic treatment)

| Report first author | Number of patients | Degree of neoplasia | Percent with buried metaplasia at baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mino-Kenudson et al. (8) | 41 | HGD, superficial or invasive adenocarcinoma | 0% |

| Ban et al. (10) | 33 | HGD or superficial adenocarcinoma | 27.3% |

| Bronner et al. (15) | 208 | HGD | 5.8% in treatment group 2.9% in control group |

| Shaheen et al. (18) | 127 | LGD or HGD | 25.2% |

| Chennat et al. (19) | 47 | HGD or IMC | 28% |

HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMC, intramucosal carcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

Frequency of buried metaplasia after PDT

We identified 22 studies, which included 953 patients, describing the frequency of buried metaplasia after PDT; follow-up intervals ranged from 4 weeks to > 5 years (Table 3) (8–12,14,15,20–34). Seventeen studies included patients who had PDT for HGD, intramucosal carcinoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma (8–12,14,15,20–24,28,29,32–34), and five studies were limited to patients who had PDT for low-grade dysplasia or non-dysplastic Barrett's esophagus (25–27,30,31). Only three articles reported the number of biopsy specimens examined (8,10,15), and none provided information on the depth of the biopsy specimens. Four reports did not describe specific mandated protocols for biopsy sampling of the neosquamous epithelium (20,22,31,33). Buried metaplasia was detected after PDT in 18 of the 22 studies (8–12,14,15,20–23,25–28,32–34), whereas 4 reports stated that buried metaplasia was not detected in any post-PDT esophageal biopsy specimens (24,29–31). In total, buried metaplasia was observed in 135 (14.2%) of the 953 patients. (Note: A number of the reports in Table 3 share the same authors, and we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients were included in more than one series.) The highest reported frequency of buried metaplasia (51.5%) was described in a study of 33 patients who had HGD or early cancer in Barrett's esophagus, and who were followed for a mean duration of 16.7 months after PDT (10).

Table 3.

Reported frequency of buried metaplasia after photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus

| Report first author | Degree of neoplasia | Number of patients | Number of biopsies | Mandated surveillance biopsy protocol | Biopsy depth | Duration of follow-up | Percent found to have buried metaplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronner et al. (15) | HGD | 138 treated 70 controls |

23,498 treated 10,160 controls |

Yes | NR | 5 Years | 30% in treatment group 33% in control group |

| Hornick et al. (20) | HGD, EC, IA | 12 | NR | No | NR | 3–38 Months | 25% |

| Schembre et al. (21) | HGD, IMC | 42 (PDT arm) | NR | Yes | NR | Median 20 months | 11.9% |

| Mino-Kenudson et al. (8) | HGD, superficial carcinoma, or IA | 52 | 1302 | Yes | NR | Mean 29.3 months | 17.3% with buried metaplasia 25% with buried neoplasia (HGD, LGD, or AC) |

| Fourolis and Thorpe (22) | HGD, IMC, or T2 AdenoCa | 31 | NR | Surveillance mandated, biopsy protocol NR | NR | Median 14 months | 20% (5 of 25 with HGD or IMC before treatment) |

| Ragunath et al. (11) | HGD, LGD | 13 | NR | Yes | NR | 12 Months | 7.7% |

| Peters et al. (23) | HGD, EC | 28 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 19 months | 25% |

| Ban et al. (10) | HGD, EC | 33 | 478 | Yes | NR | Mean 16.7 months | 51.5% |

| Etienne et al. (24) | HGD, IMC | 12 | NR | Yes | NR | Mean 34 months | 0% |

| Hage et al. (25) | No dysplasia, LGD | 24 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 12 months | 4.2% |

| Kelty et al. (26) | No dysplasia | 25 | NR | Yes | NR | 4 Weeks | 24% |

| Kelty et al. (27) | No dysplasia | 34 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 12 months | 24% |

| Wolfsen et al. (28) | HGD and IMC | 102 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 1.6 years | 4% |

| Overholt et al. (9) | LGD, HGD, EC | 102 | NR | Yes | NR | Mean 50.65 months | 3% |

| Wolfsen et al. (14) | HGD EC |

48 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 18.5 months | 2.1% |

| Buttar et al. (29) | IMC, IA | 17 | NR | Yes | NR | Mean 13 months | 0% |

| Ackroyd et al. (30) | LGD | 18 | NR | Yes | NR | 2 Years | 0% |

| Ackroyd et al. (31) | LGD | 40 | NR | Surveillance mandated, biopsy protocol NR | NR | 12 Months | 0% |

| Overholt et al. (12) | HGD or EC | 100 | NR | Yes | NR | Mean 19 months | 5% |

| Gossner et al. (32) | HGD or EC | 32 | NR | Yes | NR | NR | 6.25% |

| Barr et al. (33) | HGD | 5 | NR | “Multiple biopsies” Q 2 months | NR | 26–44 Months | 40% |

| Overholt and Panjehpour (34) | EC, HGD, LGD, No dysplasia | 45 | NR | Yes | NR | 6–66 Months | 4.4% |

EC, early cancer; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IA, invasive adenocarcinoma; IMC, intramucosal carcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; NR, not reported.

Note: A number of reports share the same authors, and we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients were included in more than one series.

Only one study included information on the frequency of buried metaplasia in control subjects with Barrett's esophagus who were followed but who did not receive PDT (15). In that randomized trial of PDT for patients with HGD, buried metaplasia was noted infrequently at baseline in both the treatment and control groups (5.8% of 138 patients who later received PDT and 2.9% of 70 control patients who did not receive PDT, P=NS). Both patient groups had similar follow-up surveillance protocols, which included omeprazole treatment and extensive esophageal biopsy sampling. Buried metaplasia developed at a similar rate in both groups (30% in the PDT group and 33% in the control group, P=NS). Since the two groups had a similar incidence of buried metaplasia during follow-up, the authors concluded that PDT was not responsible for the buried glands.

Frequency of buried metaplasia after RFA

We identified 18 studies, which included 1,004 patients who had follow-up biopsy sampling of neosquamous epithelium, that described the frequency of buried metaplasia after RFA; follow-up intervals ranged from 8 weeks to 5 years (Table 4) (18,35–51). Fifteen of the eighteen studies described specific mandated surveillance intervals and biopsy protocols (18,35–37,39,41–43,45–51). Only two studies described the depth of biopsy samples (37,41). Four studies detected buried metaplasia during follow-up (18,35,47,48), whereas fourteen did not (36–46,49–51). In total, buried metaplasia was noted in 9 (0.9%) of the 1,004 patients; 4 of the 9 patients were part of a randomized, sham-controlled trial of RFA for dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus (the AIM dysplasia trial) (18). (Note: A number of the reports in Table 4 share the same authors, and we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients were included in more than one series.)

Table 4.

Frequency of buried metaplasia following radiofrequency ablation for Barrett's esophagus

| Report first author | Degree of neoplasia | Number of patients | Number of biopsies | Mandated surveillance biopsy protocol | Biopsy depth | Duration of follow-up | Percentage of patients found to have buried metaplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herrero et al. (35) | EC, HGD, LGD | 24 | 1,272 | Yes | NR | Median 29 months | 12.5% (at NSQ junction) |

| van Vilsteren et al. (36) | HGD, EC | 22 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 24 months | 0% |

| Fleischer et al. (37) | No dysplasia | 50 | 1,473 | Yes | 85% LP or deeper | 5 Years | 0% |

| Lyday et al. (38) | No dysplasia, IND, LGD, HGD | 338 in < 1 year cohort 137 in > 1 year cohort |

NR | No | NR | Median 9 months Median 20 months | 0% in both cohorts |

| Pouw et al. (39) | HGD or EC | 24 | 1,201 | Yes | NR | Median 22 months | 0% |

| Eldaif et al. (40) | No dysplasia, LGD | 27 | NR | No | NR | 8 Weeks | 0% |

| Pouw et al. (41) | HGD or EC | 16 | 385 | Yes | 37–51% LP or deeper | Median 26 months | 0% |

| Shaheen et al. (18) | LGD, HGD | 84 | 9,517 | Yes | NR | 12 Months | 5.1% |

| Sharma et al. (42) | LGD, HGD | 62 | > 2,500 | Yes | NR | Median 24 months | 0% |

| Vassiliou et al. (43) | All grades including no dysplasia | 15 | NR | Yes | NR | Median 20.3 months | 0% |

| Ganz et al. (44) | HGD | 142 | NR | No | NR | 12 Months | 0% |

| Gondrie et al. (45) | HGD, IMC | 12 | 363 | Yes | NR | Median 14 months | 0% |

| Gondrie et al. (46) | HGD, IMC | 11 | 473 | Yes | NR | Median 19 months | 0% |

| Hernandez et al. (47) | No dysplasia, LGD, HGD | 10 | 247 | Yes | NR | 3–38 Months | 10% |

| Pouw et al. (48) | HGD, EC | 44 | 1,475 | Yes | NR | Median 21 months | 2.7% |

| Sharma et al. (49) | No dysplasia, LGD | 10 | 886 | Yes | NR | 2 Years | 0% |

| Roorda et al. (50) | LGD, HGD | 13 | NR | Yes | NR | Mean 12 months | 0% |

| Sharma et al. (51) | No dysplasia | 100 | 4,306 | Yes | NR | 12 Months | 0% |

EC, early cancer; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMC, intramucosal cancer; IND, indefinite for dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; LP, lamina propria.

Note: A number of reports share the same authors, and we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients were included in more than one series.

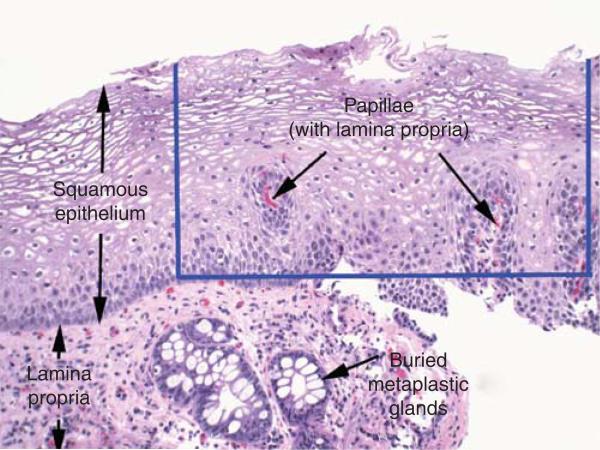

Adequacy of biopsy specimens of neosquamous epithelium

Biopsy specimens that do not include subepithelial lamina propria have a low likelihood of revealing buried metaplasia (see Figure 3). As noted above, only a small minority of reports describe the depth of neosquamous biopsy specimens taken after endoscopic ablation therapy (0 of 22 reports for PDT and 2 of 18 reports for RFA). One of the two studies that provided information on the depth of neosquamous pinch biopsy specimens found that 85% of 1,473 esophageal biopsy specimens obtained after RFA “contained lamina propria or deeper tissue” (37). However, this report does not provide information on whether specimens included only lamina propria in papillae or whether subepithelial lamina propria was present (see Figure 3). The other study, in which biopsy specimens of neosquamous epithelium obtained from 16 patients who had RFA were reviewed by three expert gastrointestinal pathologists, found that only 37% of neosquamous pinch biopsies included lamina propria or deeper stromal tissue (41). The investigators found no significant difference in biopsy depth for specimens taken with “jumbo” biopsy forceps vs. standard biopsy forceps, but they did find that “keyhole” biopsy sampling, in which a second pinch biopsy specimen was obtained from the original biopsy site, significantly increased the percentage of samples that included lamina propria or deeper stromal tissue to 51% . The study also evaluated endoscopic resection specimens of neosquamous epithelium taken from 14 patients. All of those specimens included submucosal tissue, and none revealed buried metaplasia.

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of a pinch biopsy specimen of neosquamous mucosa showing buried metaplastic glands in the subepithelial lamina propria (H&E, magnification ×40). The blue lines delimit a hypothetical biopsy specimen that contains only the epithelial layer. Note that this hypothetical specimen includes papillae, and so could be categorized as containing “lamina propria.” This categorization belies the true depth of the hypothetical biopsy specimen, because such a specimen is not informative for buried metaplasia.

It has been proposed that neosquamous epithelium may be more resistant to deep biopsy sampling than native squamous epithelium, perhaps due to scarring or other effects of the ablation procedure. To explore this issue, Shaheen et al. (52) conducted a secondary analysis of biopsy specimens taken during the AIM dysplasia trial, and found that there was no significant difference in the frequency of esophageal squamous biopsy samples that included lamina propria between patients who received RFA (78.4% of biopsy samples included lamina propria) and those who received sham ablation (79.1% , P=NS). Overholt et al. (53) also found no significant difference in the depth of esophageal squamous epithelium biopsy samples before and after PDT. These studies suggest that RFA and PDT have no important effects on the depth of squamous biopsy samples. However, the photomicrographs included in the report on RFA make it clear that specimens containing squamous epithelium with lamina propria only within papillae (without subepithelial lamina propria) were categorized as “containing lamina propria” (52). Such specimens are less informative for detection of buried metaplasia.

DISCUSSION

A number of key points emerge from this systematic review of reports that evaluated buried metaplasia after endoscopic ablation of Barrett's esophagus. First, in patients who have not had endoscopic ablation, buried metaplasia often can be found in areas where metaplastic columnar epithelium abuts squamous epithelium. This occurs at the endoscopic Z-line (the squamo-columnar junction), where buried metaplasia has been observed in up to 28% of patients (19), and at squamous islands, in which buried metaplasia has been found in up to 38.5% of cases (17). Second, endoscopic ablation can bury metaplastic glands that either are already neoplastic or have neoplastic potential. We found descriptions of 34 patients who had neoplasia within buried metaplasia detected during follow-up intervals that ranged from 4 to 52 months after ablation (mostly PDT). Third, buried metaplasia has been found more frequently after PDT than after RFA. In 22 reports describing the results of PDT for 953 patients with Barrett's esophagus, buried metaplasia was found in 135 (14.2%) during follow-up intervals that ranged from 4 weeks to > 5 years. In 18 reports describing the results of RFA for 1,004 patients, in contrast, buried metaplasia was found in only 9 (0.9%) during follow-up intervals that ranged from 8 weeks to 5 years. Furthermore, we found no report of neoplasia in buried metaplasia after RFA. Finally, none of the reports described specifically whether biopsy specimens of neosquamous epithelium contained sufficient subepithelial lamina propria to be informative for the evaluation of buried metaplasia.

The precise frequency of buried metaplasia at baseline (before endoscopic ablation) remains unclear. None of the reports listed in Table 2 describe biopsy protocols that were designed to sample esophageal squamous epithelium at baseline. Rather, the protocols mandated baseline biopsy sampling only of metaplastic columnar epithelium. Endoscopists generally do not attempt to sample squamous epithelium during endoscopic evaluation of Barrett's esophagus. Since buried glands can be detected only in biopsy specimens that have a surface layer of squamous epithelium, buried metaplasia detected at baseline was probably identified in biopsy specimens that the endoscopist had intended to take from columnar metaplasia, but fortuitously contained squamous epithelium as well (for instance, in metaplastic epithelium located near the endoscopic Z-line or adjacent to squamous islands). Therefore, it is not clear whether the wide range of reported prevalence rates for baseline buried metaplasia (0–28%) is the result of disparities in patient populations or differences in biopsy sampling practices among endoscopists.

By definition, buried metaplasia is located in the lamina propria (Figure 3). After ablation, the reported frequency with which endoscopic pinch biopsy specimens of neosquamous epithelium include lamina propria ranges from 12.9% to 91% (53,54). The reasons underlying the wide range and large disparities among studies are not clear, but differences in the criteria by which the depth of a biopsy sample is categorized may be responsible. The mere presence of “lamina propria” in squamous biopsy specimens does not guarantee that those specimens are informative for evaluation of buried metaplasia.

Lamina propria is the layer of loose connective tissue that is located mostly below the epithelium (subepithelial lamina propria), but lamina propria is also found within papillae that extend up into the epithelium (Figure 3). Although buried metaplastic glands may be detected within the lamina propria papillae, this is a rare finding in our experience. Rather, the vast majority of buried glands reside in the subepithelial lamina propria. Therefore, biopsy specimens that include only squamous epithelium with papillae (without subepithelial lamina propria) may be categorized as “containing lamina propria,” but such biopsies are less informative for evaluation of the presence or absence of buried metaplasia. Figure 3 illustrates this point.

Although some studies used the presence of lamina propria as an index of biopsy depth, none of the articles included in this review described specifically how frequently biopsy specimens of neosquamous epithelium were informative for evaluation of buried metaplasia. Only a study by Gupta et al. (54) (published in abstract form) has used a system for scoring the adequacy of esophageal biopsy specimens that included a specific assessment of subepithelial lamina propria. Among 193 pinch biopsy specimens of esophageal squamous mucosa (29 native squamous and 164 neosquamous), only 12.9% had subepithelial lamina propria; and therefore, the authors concluded that most biopsies of neosquamous epithelium are not adequate to rule out buried meta-plasia. We propose that future studies on this issue should provide specific information on how frequently biopsy specimens are informative for buried metaplasia.

It is conceivable that vagaries in the techniques used for biopsy sampling and tissue processing might result in spurious diagnoses of buried metaplasia. For example, tangential (rather than perpendicular) biopsy sampling of squamo-columnar junctional mucosa combined with poor orientation of the paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens might yield tissue sections in which glands appear to be “buried” under squamous epithelium when in fact they are not. This type of artifact is especially likely to occur in patients who have residual islands of columnar metaplasia post-ablation and, hence, numerous junctions between squamous and columnar mucosae. Furthermore, the detection of residual islands is enhanced by the use of modern endoscopic techniques, such as high resolution endoscopy and narrow band imaging, both of which have become widely available only within the past 5 years or so (55). Many of the PDT studies listed in Table 3 were conducted at a time when only standard endoscopy was available to the researchers whereas, in contrast, high resolution endoscopy was available for most of the RFA studies listed in Table 4 . Thus, enhanced detection of meta-plasia with the use of high resolution endoscopy in the modern RFA studies would be expected to result in more complete ablations and less inadvertent biopsy sampling of residual metaplastic islands. Conversely, the use of inferior endoscopic imaging in older PDT studies might have contributed to a higher frequency of buried metaplasia in those reports.

Another issue that might confound the results of studies on buried metaplasia is whether the biopsy specimens allegedly taken from neosquamous epithelium in fact contain neosquamous epithelium. There are no endoscopic features that distinguish neosquamous from native squamous epithelium. Consequently, endoscopists rely on endoscopic measurements taken before ablation to determine the axial level (i.e., distance from the incisor teeth) at which to sample for neosquamous epithelium. After ablation, the validity of axial measurements, which can be affected by respiration, esophageal contraction and the degree of esophageal air distention, has not been established. Furthermore, metaplastic columnar epithelium often does not involve the esophagus in a circumferential manner, but rather in an eccentric manner with irregular, finger-like projections of metaplasia extending up the esophagus. Therefore, even if the axial level of neosquamous epithelium is determined accurately, it may be missed due to the inaccurate radial orientation of the biopsy sampling.

The risk of cancer associated with buried metaplasia is unclear, and authorities have proposed plausible hypotheses for why that risk might be greater or less than that of the native, surface meta-plastic epithelium. For example, it has been proposed that genetic abnormalities acquired during carcinogenesis might convey survival advantages that render neoplastic Barrett's cells more resistant than non-neoplastic cells to ablative therapies (56). If this is true, then ablative therapies might be better suited to destroy normal cells than neoplastic ones, and ablation might be predisposed to bury neoplastic cells that have a high risk of malignancy. However, none of the studies reviewed in this report provide strong support for that hypothesis. Other authorities have suggested that the overlying layer of neosquamous epithelium protects buried metaplastic cells from the carcinogenic effects of refluxed acid and bile. In support of this hypothesis, one group found fewer DNA content abnormalities and lower crypt proliferation rates in buried metaplasia than in the surface metaplastic epithelium (20). However, the reliability of DNA content and proliferation rates for predicting cancer risk is controversial. Dysplasia is the histological finding used clinically to predict cancer risk in Barrett's esophagus, but the histological evaluation of dysplasia in buried glands may be difficult for pathologists because of the lack of surface epithelium. When atypical crypt cells are noted, evaluation of the surface epithelium for maturation abnormalities is considered helpful in differentiating regenerative changes from dysplasia (57). Unfortunately, no studies have evaluated interobserver agreement for the grading of dysplasia within buried metaplasia.

The reports in this review also provide contradictory data on whether squamous overgrowth after ablation results in complete covering of neoplastic glands or whether a portion of those glands always remain exposed to the surface. In one study of 52 patients who had HGD or superficial adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus treated with PDT, 13 (25%) were found to have buried neoplasms during a mean follow-up interval of 29.3 months (8). In eight of those patients, the highest grade neoplastic glands were detected entirely beneath neosquamous epithelium. In contrast, in a study by Bronner et al. (15) in which > 30,000 esophageal biopsy specimens taken from 208 patients in a randomized trial of PDT for HGD in Barrett's esophagus were reviewed, the highest grade neoplastic glands were not present exclusively beneath neosquamous epithelium in any patient. Unfortunately, it is not clear what percentage of biopsy specimens in either study contained sufficient subepithelial lamina propria to be informative for evaluation of buried metaplasia. It is also important to note that, although subsquamous neoplastic cells are not visible to the endoscopist, subsquamous neoplasms often cause structural abnormalities (e.g., strictures and lumps) that are apparent endoscopically. Finally, the mere finding of an adenocarcinoma with a subsquamous component in the esophagus does not establish that the neoplasm arose from subsquamous glands.

In summary, our systematic review reveals that the frequency and importance of buried metaplasia after endoscopic ablation of Barrett's esophagus remain unclear. For patients treated with RFA, the frequency of buried metaplasia appears to be low, and it is reassuring that there are no reports of neoplasia appearing in buried metaplasia after this procedure. However, RFA has been used primarily to treat Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia, and it can take many years for dysplasia to evolve into cancer. RFA also has been used to ablate Barrett's esophagus without dysplasia, which can take decades to progress to cancer. RFA is a relatively new procedure and, therefore, available studies on RFA describe only brief follow-up intervals. The fact that buried neoplasia has not been observed in patients treated with RFA who have been followed for 5 years does not eliminate the possibility of buried metaplasia that has malignant potential. Further studies that pay special attention to the adequacy of neosquamous biopsy specimens are needed to resolve this issue.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by the Office of Medical Research, Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA134571). The study sponsors had no role in the in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data and in the writing of the report.

Footnotes

Specific author contributions: Planning and performance of the systematic review including article selections and data abstraction, resolution of discrepancies, drafting/revision of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation: Nathan A. Gray; resolution of discrepancies in the systematic review process, drafting/revision of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation: Robert D. Odze; planning and performance of the systematic review including article selections and data abstraction, resolution of discrepancies, supervision, drafting/revision of the manuscript, analysis and interpretation: Stuart Jon Spechler; all authors approved the final draftof the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Stuart Jon Spechler, MD.

Potential competing interests: Spechler has received research support from B Â RRX Medical.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spechler SJ, Fitzgerald RC, Prasad GA, et al. History, molecular mechanisms, and endoscopic treatment of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:854–69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:142–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Biomarkers and photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus: time to FISH or cut bait? Gastroenterology. 2008;135:354–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Stem cells in Barrett's esophagus: HALOs or horns? Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:41–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shand A, Dallal H, Palmer K, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in columnar lined oesophagus following treatment with argon plasma coagulation. Gut. 2001;48:580–1. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.580b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Laethem JL, Peny MO, Salmon I, et al. Intramucosal adenocarcinoma arising under squamous re-epithelialisation of Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 2000;46:574–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mino-Kenudson M, Ban S, Ohana M, et al. Buried dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma arising in barrett esophagus after porfimer-photodynamic therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:403–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213407.03064.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overholt BF, Panjehpour M, Halberg DL. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia and/or early stage carcinoma: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:183–8. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ban S, Mino M, Nishioka NS, et al. Histopathologic aspects of photodynamic therapy for dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett's esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1466–73. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000141392.91677.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ragunath K, Krasner N, Raman VS, et al. Endoscopic ablation of dysplastic Barrett's oesophagus comparing argon plasma coagulation and photodynamic therapy: a randomized prospective trial assessing effi cacy and cost-effectiveness. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:750–8. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overholt BF, Panjehpour M, Haydek JM. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus: follow-up in 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70437-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonavina L, Ceriani C, Carazzone A, et al. Endoscopic laser ablation of nondysplastic Barrett's epithelium: is it worthwhile? J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:194–9. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfsen HC, Woodward TA, Raimondo M. Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1176–81. doi: 10.4065/77.11.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bronner MP, Overholt BF, Taylor SL, et al. Squamous overgrowth is not a safety concern for photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:56–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.012. quiz 351–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biddlestone LR, Barham CP, Wilkinson SP, et al. The histopathology of treated Barrett's esophagus: squamous reepithelialization after acid suppression and laser and photodynamic therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:239–45. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199802000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma P, Morales TG, Bhattacharyya A, et al. Squamous islands in Barrett's esophagus: what lies underneath? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:332–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chennat J, Ross AS, Konda VJ, et al. Advanced pathology under squamous epithelium on initial EMR specimens in patients with Barrett's esophagus and high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal carcinoma: implications for surveillance and endotherapy management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:417–21. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hornick JL, Mino-Kenudson M, Lauwers GY, et al. Buried Barrett's epithelium following photodynamic therapy shows reduced crypt proliferation and absence of DNA content abnormalities. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schembre DB, Huang JL, Lin OS, et al. Treatment of Barrett's esophagus with early neoplasia: a comparison of endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foroulis CN, Thorpe JA. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia or early cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters F, Kara M, Rosmolen W, et al. Poor results of 5-aminolevulinic acid-photodynamic therapy for residual high-grade dysplasia and early cancer in barrett esophagus after endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 2005;37:418–24. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etienne J, Dorme N, Bourg-Heckly G, et al. Photodynamic therapy with green light and m-tetrahydroxyphenyl chlorin for intramucosal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:880–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hage M, Siersema PD, van Dekken H, et al. 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy versus argon plasma coagulation for ablation of Barrett's oesophagus: a randomised trial. Gut. 2004;53:785–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelty CJ, Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, et al. Comparison of high- vs low-dose 5-aminolevulinic acid for photodynamic therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:452–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelty CJ, Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, et al. Endoscopic ablation of Barrett's oesophagus: a randomized-controlled trial of photodynamic therapy vs. argon plasma coagulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1289–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfsen HC, Hemminger LL, Wallace MB, et al. Clinical experience of patients undergoing photodynamic therapy for Barrett's dysplasia or cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1125–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buttar NS, Wang KK, Lutzke LS, et al. Combined endoscopic mucosal resection and photodynamic therapy for esophageal neoplasia within Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:682–8. doi: 10.1067/gien.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, Davis MF, et al. Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett's oesophagus: a prospective, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2000;47:612–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ackroyd R, Brown NJ, Davis MF, et al. Aminolevulinic acid-induced photodynamic therapy: safe and effective ablation of dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gossner L, Stolte M, Sroka R, et al. Photodynamic ablation of high-grade dysplasia and early cancer in Barrett's esophagus by means of 5-amino-levulinic acid. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:448–55. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barr H, Shepherd NA, Dix A, et al. Eradication of high-grade dysplasia in columnar-lined (Barrett's) oesophagus by photodynamic therapy with endogenously generated protoporphyrin IX. Lancet. 1996;348:584–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)03054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Overholt BF, Panjehpour M. Photodynamic therapy in Barrett's esophagus. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1996;14:245–9. doi: 10.1089/clm.1996.14.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrero LA, van Vilsteren FG, Pouw RE, et al. Endoscopic radio-frequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for early neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus longer than 10 cm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:682–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Vilsteren FG, Alvarez Herrero L, Pouw RE, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for the endoscopic eradication of esophageal squamous high grade intraepithelial neoplasia and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2011;43:282–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleischer DE, Overholt BF, Sharma VK, et al. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for Barrett's esophagus: 5-year outcomes from a prospective multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2010;42:781–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyday WD, Corbett FS, Kuperman DA, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of Barrett's esophagus: outcomes of 429 patients from a multicenter community practice registry. Endoscopy. 2010;42:272–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pouw RE, Wirths K, Eisendrath P, et al. Effi cacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for barrett's esophagus with early neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eldaif SM, Lin E, Singh KA, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of Barrett's esophagus: short-term results. Ann Th orac Surg. 2009;87:405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.043. discussion 410–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pouw RE, Gondrie JJ, Rygiel AM, et al. Properties of the neosquamous epithelium after radiofrequency ablation of Barrett's esophagus containing neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1366–73. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma VK, Jae Kim H, Das A, et al. Circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett's esophagus containing dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:310–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vassiliou MC, von Renteln D, Wiener DC, et al. Treatment of ultralong-segment Barrett's using focal and balloon-based radiofrequency ablation. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:786–91. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganz RA, Overholt BF, Sharma VK, et al. Circumferential ablation of Barrett's esophagus that contains high-grade dysplasia: a US Multicenter Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gondrie JJ, Pouw RE, Sondermeijer CM, et al. Effective treatment of early Barrett's neoplasia with stepwise circumferential and focal ablation using the HALO system. Endoscopy. 2008;40:370–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gondrie JJ, Pouw RE, Sondermeijer CM, et al. Stepwise circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett's esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: results of the first prospective series of 11 patients. Endoscopy. 2008;40:359–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernandez JC, Reicher S, Chung D, et al. Pilot series of radiofrequency ablation of Barrett's esophagus with or without neoplasia. Endoscopy. 2008;40:388–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pouw RE, Wirths K, Eisendrath P, et al. Efficacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for barrett's esophagus with early neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;8:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma VK, Kim HJ, Das A, et al. A prospective pilot trial of ablation of Barrett's esophagus with low-grade dysplasia using stepwise circumferential and focal ablation (HALO system). Endoscopy. 2008;40:380–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roorda AK, Marcus SN, Triadafilopoulos G. Early experience with radio-frequency energy ablation therapy for Barrett's esophagus with and without dysplasia. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:516–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma VK, Wang KK, Overholt BF, et al. Balloon-based, circumferential, endoscopic radiofrequency ablation of Barrett's esophagus: 1-year follow-up of 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaheen NJ, Peery AF, Overholt BF, et al. Biopsy depth after radio-frequency ablation of dysplastic Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:490–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Overholt BF, Dean PJ, Galanko JA, et al. Does ablative therapy for Barrett esophagus affect the depth of subsequent esophageal biopsy as compared with controls? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:676–81. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181dadaf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta N, Mathur SC, Singh V, et al. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for post-ablation surveillance in Barrett's esophagus (BE)? Digestive Disease Week. 2010 May 1–5; doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.040. Abstract # 94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curvers WL, Bansal A, Sharma P, et al. Endoscopic work-up of early Barrett's neoplasia. Endoscopy. 2008;40:1000–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasad GA, Wang KK, Halling KC, et al. Utility of biomarkers in prediction of response to ablative therapy in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:370–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lomo LC, Blount PL, Sanchez CA, et al. Crypt dysplasia with surface maturation: a clinical, pathologic, and molecular study of a Barrett's esophagus cohort. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:423–35. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]