Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is an important biological molecule that regulates ion transport and inflammatory responses in epithelial tissue. The present study examined whether the adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin, would increase cAMP concentration in porcine vocal fold mucosa and whether the effects of increased cAMP would be manifested as a functional increase in transepithelial ion transport. Additionally, changes in cAMP concentrations following exposure to an inflammatory mediator, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) were investigated.

Study Design

In vitro experimental design with matched treatment and control groups.

Methods

Porcine vocal fold mucosae (N = 30) and tracheal mucosae (N = 20) were exposed to forskolin, TNFα, or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) treatment. cAMP concentrations were determined with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Ion transport was measured using electrophysiological techniques.

Results

Thirty minute exposure to forskolin significantly increased cAMP concentration and ion transport in porcine vocal fold and tracheal mucosae. However, 30-minute and 2-hour exposure to TNFα did not significantly alter cAMP concentration.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that forskolin-sensitive adenylyl cyclase is present in vocal fold mucosa, and further, that the product, cAMP increases vocal fold ion transport. The results presented here contribute to our understanding of the intracellular mechanisms underlying vocal fold ion transport. As ion transport is important for maintaining superficial vocal fold hydration, data demonstrating forskolin-stimulated ion transport in vocal fold mucosa suggest opportunities for developing pharmacological treatments that increase surface hydration.

Keywords: cAMP, vocal folds, ion transport, forskolin, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Vocal fold surface hydration is necessary to initiate and sustain vocal fold oscillation for voice production.1 Depletion of vocal fold surface hydration has negative consequences on phonation. There has therefore been tremendous interest in identifying factors that cause vocal fold drying, in addition to identifying mechanisms that regulate vocal fold hydration. Laryngeal inflammation and disease are associated with superficial vocal fold dehydration.2,3 Superficial vocal fold drying may also be induced by aging,4 systemic dysfunction,5 inhaling dessicated air,6 and reduced water intake.7 Mechanisms that maintain vocal fold surface hydration include glandular secretions and mucociliary clearance of airway surface fluid lining the distal respiratory tract.8 Recently, the role of transepithelial ion transport in regulating vocal fold hydration has also been investigated.9–11 In ciliated columnar epithelia lining the airway, ion transport provides the osmotic gradient for water movement which contributes to surface hydration.12 Therefore, ion transport has been pharmacologically manipulated using ion channel inhibitors and agonists to increase surface hydration.12 As the stratified squamous epithelia of the vocal folds differ from the ciliated columnar epithelia lining the airway, the identification of ion transport mechanisms in the vocal fold epithelium is of interest because of the potential to develop treatments that increase superficial hydration.

An improved understanding of ion transport mechanisms in vocal fold mucosa is emerging. Fisher et al.9 demonstrated that transepithelial water and ion movement across ovine vocal fold mucosa is associated with the Na+K+ATP pump. Other key transport proteins that play an important role in airway hydration12 have also been localized to ovine vocal fold mucosa. Specifically, the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC), the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) channel, and the aquaporin water channels (AQP-1 and AQP-2) have been identified, and may provide a pathway for regulation of surface hydration.10,11 In bronchial, tracheal, and nasal mucosa, all three of these channels are positively regulated by agonists that cause increased production of the intracellular secondary messenger, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and it is possible that increased cAMP in vocal fold mucosa also increases ion transport. However, the presence of a regulated pool of cAMP in porcine vocal fold mucosa has not been demonstrated thus far. Experimental protocols typically use forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase, to raise cAMP concentration to study the functional outcome of increased cAMP on ion transport in individual tissues. The present study will also apply forskolin to vocal fold mucosae to verify stimulatory increases in cAMP, and to study the effects of increased intracellular cAMP on ion transport.

cAMP is an important biological molecule. cAMP regulates ion transport and also acts as a secondary messenger for a variety of inflammatory mediators.13 For example, the potent primary inflammatory mediator, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) has been shown to reduce production of cAMP in human neutrophils.14 Agents that increase intracellular cAMP could therefore serve as anti-inflammatory factors via their effects on ion and water fluxes, but again there is a paucity of information on the effects of inflammatory mediators on cAMP concentration in vocal fold mucosa. TNFα is upregulated in inflamed vocal folds.15,16 Therefore, this study will examine the effects of this primary inflammatory mediator on cAMP concentrations in vocal fold mucosa in vitro.

The present study used a combination of in vitro cAMP assays and in vitro electrophysiological methods to investigate three experimental questions. Experiment 1 examined whether forskolin would increase cAMP concentration in porcine vocal fold mucosa. Experiment 2 investigated whether the increase in cAMP with forskolin would be evident as increased ion transport. As cAMP is considered an important biological molecule in the inflammatory process, exploratory experiment 3 examined the effects of inflammatory mediator (TNFα) exposure on cAMP concentrations. We hypothesized that 30 minute exposure to forskolin would significantly increase cAMP concentrations in porcine vocal fold mucosae. We therefore measured cAMP concentrations in porcine vocal fold mucosae using enzyme immunoanalysis. Tracheal mucosa, a tissue where forskolin is known to increase cAMP, served as procedural control. As cAMP is important for regulating ion transport, we hypothesized that 30 minute exposure to forskolin but not vehicle treatment would also significantly increase ion transport in porcine vocal fold mucosa. We therefore measured short-circuit current (ISC: a measure of net ion transport) across porcine vocal fold mucosae under basal and forskolin-stimulated conditions. Finally, as cAMP is considered a secondary mediator in the inflammatory process, we predicted that exposure to TNFα would alter cAMP concentration. We therefore compared the effects of 30 minute and 2 hour TNFα exposure on cAMP concentration in porcine vocal fold and tracheal mucosae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Preparation

Fresh larynges (N = 15) and trachea (N = 10) from young adult Ossabaw pigs (aged 6–12 months, 10 males and 5 females) were used in this study. The larynx and trachea were excised from each animal within 20 minutes of sacrifice, in accordance with approved protocols at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Larynges and trachea were transported to the laboratory in isotonic saline solution and dissected as described below, to obtain vocal fold and tracheal mucosae.

Vocal fold mucosa

Each larynx was bisected into two hemilarynges along the mid-sagittal plane following previously validated procedures.17 Next, within each hemilarynx shallow horizontal incisions were made 1 cm below and above the true vocal folds with a scalpel. The vocal fold mucosa (vocal fold epithelium with its attached basal lamina) was dissected from the underlying lamina propria. The tissue was kept moist with isotonic saline throughout the dissection procedure. The vocal fold mucosa was then prepared for cAMP assays or mounted on Ussing chambers for electrophysiology investigations. For the cAMP experiments involving exposure to inflammatory mediator (experiment 3), each vocal fold was bisected yielding four vocal fold samples from each larynx.

Tracheal mucosa

The proximal section of the trachea was used for all investigations. Each porcine tracheum was cut along the anterior longitudinal axis to reveal posterior mucosal membrane. The tracheal mucosa was bluntly dissected from underlying connective tissue. Two to four-sections of tracheal mucosae were obtained from each animal.

Treatments

Vocal folds and tracheal mucosae were exposed to one of the following treatments: 10 μmol/L forskolin, 10 μmol/L TNFα, or 10 μmol/L TNFα + forskolin. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was the dilutent for forskolin, so DMSO was used as the vehicle treatment. All treatments were prepared in serum-free media (DMEMS/F12 base media supplemented with 25 U/mL penicillin, 25 mg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), and 12 mg/mL ciprofloxacin (Voigt Global Distribution, Kansas City, MO) just before each experiment.

Experiment 1: cAMP Concentration After Forskolin and Vehicle Treatment

Protocol

To investigate whether exposure to forskolin changed cAMP levels, porcine vocal fold (N = 14) and tracheal (N = 14) mucosae were dissected as described above, and incubated in serum free media (DMEMS) containing either vehicle (DMSO) or 10 μmol/L forskolin for 30 minutes at 37°C. All experiments were performed with paired vocal fold mucosae, such that from each larynx, one vocal fold mucosa was exposed to forskolin and the contralateral vocal fold mucosa was exposed to vehicle. Likewise, tracheal mucosae exposed to either forskolin or vehicle, were obtained from the same animal as the vocal fold mucosa. Following treatment, the samples were homogenized in 1 mL ice cold acid (0.1 mol/L HCl) supplemented with 1% Triton x-100 and centrifuged at 14,243g for 15 minutes to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C for later analysis. cAMP concentrations were determined per manufacturer’s protocols using a Direct cAMP Enzyme Immunoassay Kit (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI). Meanwhile, the protein concentration for each sample was determined using a RC/DC protein assay (Biorad; Hercules, CA). To account for variations in the amount of tissue sample, cAMP concentrations were computed as picomole/milligram protein.

Data and statistical analysis

Visual inspection and Kolmogrov-Smirnov tests confirmed that data were normally distributed. Paired t-tests were run separately for vocal fold and tracheal mucosae (SPSS 15.0, Chicago, IL). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Experiment 2: Ion Transport After Forskolin and Vehicle Treatment

Short-circuit current (ISC) is a measure of net ion transport. By convention, an increase in ISC indicates an increase in anions moving in a secretory direction (from mucosa toward the surface) or cations moving in an absorptive (into the mucosa) direction. Ion transport was measured with Ussing chambers and current voltage clamp (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL).18

Protocol

First, the Ussing system was calibrated.17,18 Dissected vocal fold mucosa was mounted on pins between two halves of an Ussing chamber. Two voltage electrodes and two current electrodes (Ag+/AgCl electrodes with Agar—3 mol/L KCl salt bridges; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) were inserted into the Ussing chamber on either side of the vocal fold membrane. Ten milliliter of serum-free media was placed in the luminal and serosal bathing reservoirs. The temperature of both reservoirs was maintained at 37°C and the tissue was kept viable by oxygenating the media with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The spontaneous transepithelial potential difference across the tissue was clamped to zero and ISC was continuously monitored as a measure of net ion transport. Transepithelial resistance was measured throughout each experiment by applying 2 mV pulses across the membrane every 200 seconds and measuring the resultant current deflection. Vocal fold mucosae were allowed to reach a stable, relatively unchanging baseline (~45 min) before the addition of effectors such as forskolin.

Use of porcine model for vocal fold ion transport studies

Previous research on vocal fold ion transport has used ovine and canine models.9,11 To confirm the use of the porcine model for ion transport studies, we first sought to establish the presence of major ion transporters (Na+ and Cl−) in porcine vocal fold mucosa. A series of experiments were performed where the vocal fold mucosa was exposed to either a Na+ channel inhibitor (amiloride, 10 μmol/L) or a Cl− channel inhibitor (NPPB: 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid, 100 μmol/L) in counterbalanced order, in the absence of forskolin. Amiloride and NPPB were only added to the apical bathing media after tissue had reached a stable baseline. At the concentrations used, amiloride is a specific inhibitor of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and NPPB is an inhibitor of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) chloride channel.

Forskolin and vehicle treatment

Having confirmed the feasibility of using porcine vocal fold mucosa for ion transport studies (see Results section), we examined whether the increase in cAMP following forskolin treatment would be functionally translated into a change in ion transport (ISC). Therefore ISC was continuously measured after treatment with either forskolin (N = 5) or vehicle (N = 5). As in experiment 1, vocal folds from each larynx were exposed to both treatments. Briefly, once the vocal fold mucosa had reached a stable baseline, 10 μmol/L forskolin or vehicle was added to both the apical and basal reservoirs and ISC was measured for 30 minutes. Baseline and posttreatment ISC were normalized to the area of the chamber (normalized ISC = ISC/1.13 cm2). The normalized ISC is hereafter referred to as the ISC (μA/cm2). To further examine whether the forskolin-stimulated changes in ISC were associated with changes in Na+ absorption or Cl− secretion, tissues were treated with amiloride or NPPB, pre- and postforskolin addition.

Data and statistical analysis

Visual inspection and Kolmogrov-Smirnov tests confirmed that data were normally distributed. After verifying that baseline ISC did not differ in vocal fold mucosae exposed to forskolin or vehicle treatment (t = 0.753, df = 4, P = .493), paired t-tests were employed to investigate whether exposure to forskolin as compared with vehicle would significantly increase ISC from baseline (SPSS 15.0). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Experiment 3: cAMP Concentration After Exposure to Inflammatory Mediator

To examine whether exposure to an inflammatory mediator (TNFα) significantly altered cAMP levels, porcine vocal fold and tracheal mucosae were incubated in TNFα (10 μmol/L); forskolin (10 μmol/L); or TNFα + forskolin at 37°C for 30 minutes (N = 6) and 2 hours (N = 6). cAMP was extracted and measured as in experiment 1.

Data and statistical analysis

Raw data violated assumptions of normality hence Friedman’s Analysis of Variance by ranks nonparametric statistics were used with treatment (TNFα, forskolin, TNFα + forskolin) as the repeated measure (SPSS 15.0). Separate Friedman statistics were applied to vocal fold and tracheal mucosae at 30 minutes and 2-hour exposures. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: cAMP Concentration After Forskolin and Vehicle Treatment

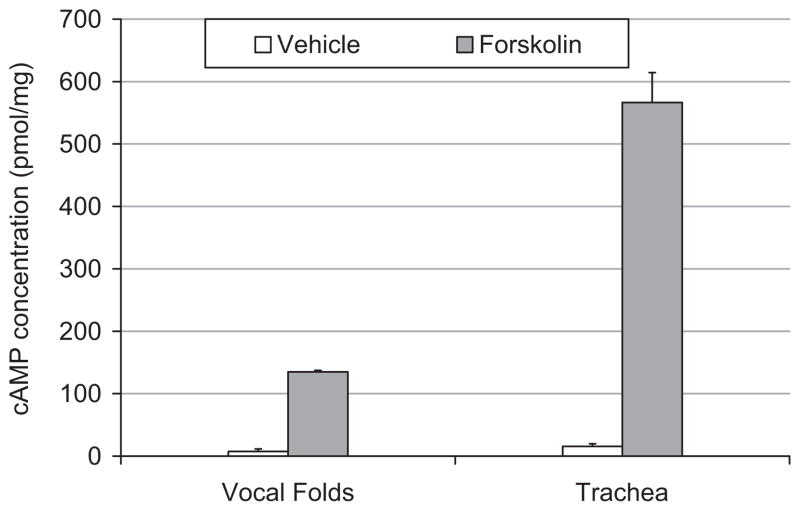

Figure 1 demonstrates the effects of 30 minute exposure to forskolin on cAMP concentrations in porcine vocal fold and tracheal mucosae. Exposure to 10 μmol/L forskolin significantly increased cAMP concentration as compared with vehicle in porcine vocal fold mucosae (t = 7.23, df = 6, P < .01). Likewise, there was a significant increase in cAMP concentrations in porcine trachea exposed to forskolin as compared with vehicle (t = 2.78, df = 6, P < .03).

Fig. 1.

Bar graph representing mean ± SE of cAMP concentration in porcine vocal fold and tracheal mucosae treated with forskolin (filled bars) or vehicle (unfilled bars).

Experiment 2: Ion Transport After Forskolin and Vehicle Treatment

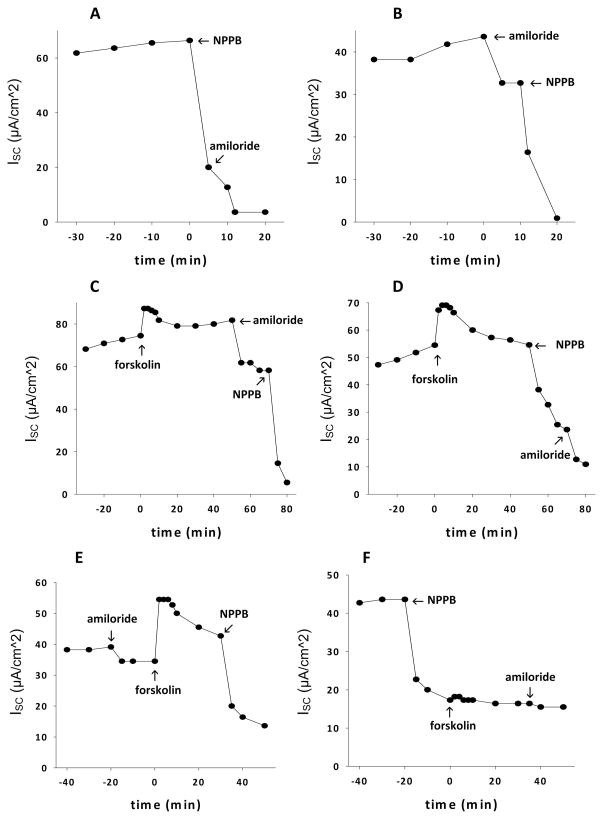

Figure 2(A–F) confirm the feasibility of using porcine vocal fold mucosae for ion transport studies. As depicted in Figures 2A and B, the predominant component of basal ISC is sensitive to NPPB whereas a smaller portion of the current is sensitive to amiloride. The directionality of ion movement indicates that basal ISC is formed by a combination of Cl− secretion and Na+ absorption, with Cl− secretion dominating. These data are consistent with previous findings in ovine vocal fold11 and support the utility of the porcine vocal fold model.

Fig. 2.

(A, B) Basal electrogenic ion transport (ISC) in porcine vocal fold mucosae before addition of either 100 μmol/L NPPB (a Cl− channel inhibitor) or 10 μmol/L amiloride (a Na+ channel inhibitor), in counterbalanced order. Basal ISC is a combination of Cl− secretion and Na+ absorption. To determine the relative contribution of each ion species (Cl− or Na+) to basal ISC, ion channel inhibitors (NPPB or amiloride) were added. The greater decrease in ISC after addition of NPPB as compared with amiloride, demonstrates that the dominant component of basal ISC is Cl− secretion. (C, D) Vocal fold mucosal response to forskolin. Forskolin was added initially, followed by 10 μmol/L amiloride and 100 μmol/L NPPB in counterbalanced order. The greater magnitude of decrease in forskolin-stimulated ISC after addition of NPPB as compared with amiloride suggests that the dominant component of ISC is still Cl− secretion. (E, F) Effects of amiloride and NPPB before the addition of forskolin. Pretreatment with 10 μmol/L amiloride did not prevent a forskolin-stimulated increase in ISC. However, pretreatment with 100 μmol/L NPPB completely abolished the stimulatory effects of forskolin on ISC, confirming that Cl− secretion is the dominant component of ISC.

Figures 2C and D demonstrate representative traces of the effects of forskolin on ISC. Forskolin caused an immediate increase in ISC. After the stimulatory response to forskolin had waned, the vocal fold mucosa remained viable. As demonstrated by the effects of amiloride and NPPB, forskolin-stimulated ISC predominantly involves Cl− secretion.

Figures 2E and F demonstrate representative traces of the effects of forskolin on ISC in vocal fold mucosae pretreated with amiloride or NPPB. Note that pretreatment with 10 μmol/L amiloride (2E) did not prevent the forskolin-induced increase in ISC. Conversely, pretreatment with NPPB (2F) completely abolished the response to forskolin, confirming that Cl− secretion is the predominant component of forskolin-stimulated ISC.

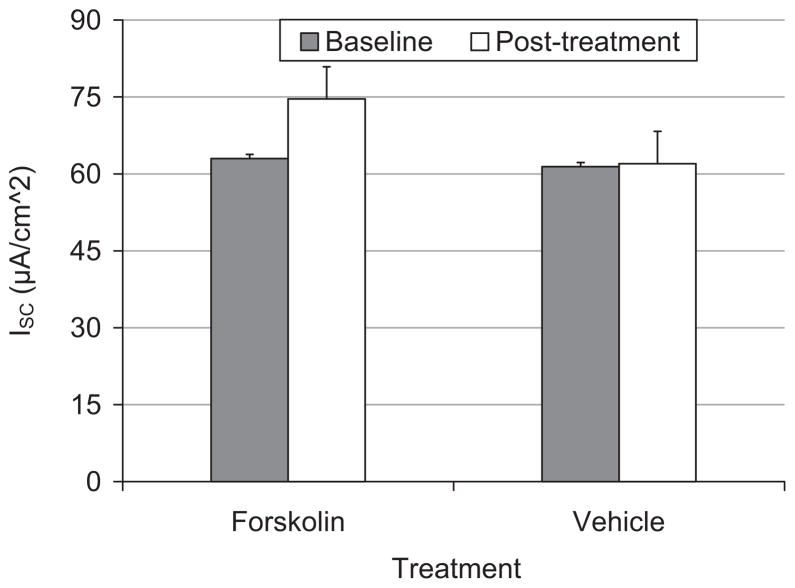

Figure 3 demonstrates the average maximal ISC response to forskolin (N = 5) and vehicle (N = 5) treated tissue. Exposure to 10 μmol/L forskolin immediately increased ISC from baseline (mean increase = 12 μA/cm2; t = 5.71, df = 4, P = .01). Conversely, exposure to vehicle did not significantly change ISC from baseline (mean increase = 1 μA/cm2; t = 1.17, df = 4, P = .31).

Fig. 3.

Bar graph representing mean ± SE of ion transport (ISC) in porcine vocal fold mucosae at pretreatment baseline (filled bars) and after treatment with forskolin or vehicle (unfilled bars).

Experiment 3: cAMP Concentration After Exposure to Inflammatory Mediator

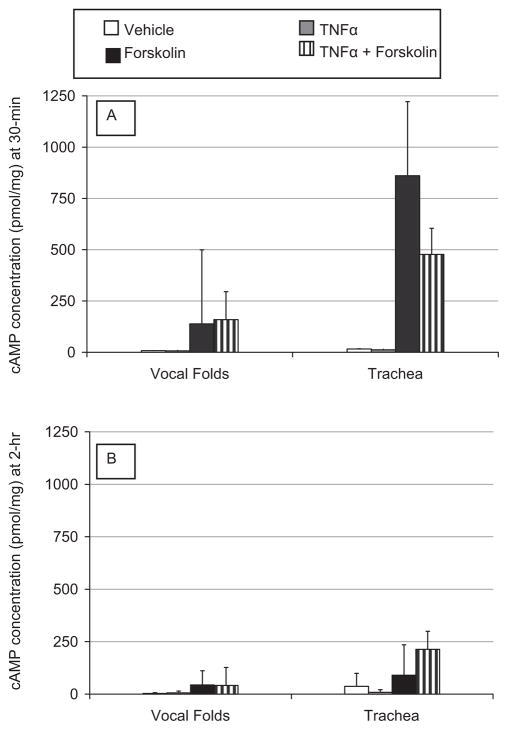

Figure 4 depicts the change in cAMP concentration after exposure to TNFα for 30 minutes (4A) and 2-hours (4B) in the presence and absence of forskolin. cAMP concentrations in vocal fold mucosae did not change significantly after exposure to TNFα for 30 minutes (χ2 = 6, df = 2, P > .05) or 2 hours (χ2 = 4.6, df = 2, P > .09). Likewise, there was no significant change in tracheal cAMP concentration after exposure to TNFα for 30 minutes (χ2 = 6, df = 2, P > .05) and 2 hours (χ2 = 4.6, df = 2, P > .09). There was high variability in the data as demonstrated by the large error bars in Figures 4A and B. It is noteworthy that data in this experiment confirmed our findings for the stimulatory effects of forskolin on cAMP levels observed in experiment 1, with even 2-hour exposure to forskolin significantly increasing cAMP concentration in vocal fold (mean increase = 43 pmol/mg) and tracheal mucosae (mean increase = 90 pmol/mg) (gray bars, Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Bar graphs representing mean ± SE of cAMP concentration in porcine vocal fold and tracheal mucosae exposed to treatments for 30 minutes (A) and 2-hours (B). Unfilled bars = vehicle; light gray bars = TNFα; dark gray bars = forskolin; striped bars = TNFα + forskolin.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the effects of forskolin on cAMP concentrations and ion transport in porcine vocal fold mucosa in vitro, and further examined whether cAMP concentration would be altered following exposure to an inflammatory mediator. cAMP in an important intracellular second messenger that regulates ion transport across the cell membrane.12 Here we demonstrate that cAMP levels are increased after brief exposure to forskolin, and that cAMP regulates ion transport in porcine vocal fold mucosae. To our knowledge, cAMP-mediated ion flux and the effects of forskolin on cAMP concentration have not been quantified previously in porcine vocal fold mucosae. Our novel findings add to the emerging literature on ion transport mechanisms and intracellular signal transduction in the vocal folds. The increase in cAMP concentration in trachea after application of forskolin is consistent with published data12 and validates the experimental techniques used in this study.

Previous research on vocal fold ion transport has used a canine or ovine model.9,11 We used a porcine model in these studies because anatomic and histological studies have demonstrated similarities between porcine and human vocal folds.19,20 For example, the biomolecular composition of porcine vocal folds is more similar to humans than other commonly used animal species. Furthermore, the nature of junctional complexes in stratified squamous epithelia of porcine vocal folds is similar to human vocal folds.

To document the feasibility of using the porcine model for ion transport studies, we conducted a series of experiments to confirm the presence of Na+ and Cl− transport in vocal fold mucosae (Figs. 2A–E). We focused on Na+ and Cl− as these are the primary ions mediating salt and water transport in the respiratory airway,12 and because these ions transporters have been localized to the vocal fold mucosa, and regulate superficial hydration.9,11 Based on the directionality of vocal fold ion movement (Figs. 2A and B), we suggest that basal ISC (before forskolin treatment) is a combination of Cl− secretion and Na+ absorption with the Cl− secretory response dominating. The addition of forskolin caused an immediate, albeit transient increase in ion flux. However, once this transient response returned to baseline, Cl− secretion remained the dominant ion flux. Addition of amiloride or NPPB before forskolin treatment further demonstrated that increases in intracellular cAMP stimulated both ENaC driven Na+ absorption and CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion, with the latter comprising the majority of stimulated ISC. As increased Cl− efflux in epithelial tissue is accompanied by increased water secretion, treatment with forskolin could enhance superficial vocal fold hydration. However, the feasibility of using forskolin as a pharmacological treatment awaits further investigation.

Besides playing an important role in regulating ion transport, cAMP also acts as a secondary messenger for a variety of inflammatory mediators in biological tissue. But again, the effects of inflammatory mediators on cAMP in vocal fold mucosae are not known despite the potential for vocal fold exposure to inflammatory perturbations associated with smoke particulate, inhaled pollutants and allergens, laryngopharyngeal reflux, intubation, and impact stress. Knowledge of the intracellular molecules mediating vocal fold response to inflammatory mediators is essential, to develop pharmacological treatments to prevent the negative phonatory consequences associated with inflammation such as vocal fatigue, dysphonia, and laryngeal disease.15,21–25

TNFα is a potent primary inflammatory mediator that is upregulated after an inflammatory perturbation.15 TNFα can trigger a series of cellular events including expression of nitric oxide synthase, induction of adhesion molecules, and expression of other inflammatory cytokines. The presence of TNFα has been confirmed after an episode of acute vocal fold inflammation. Verdolini et al.16 used a single subject design to demonstrate an increase in TNFα concentration of vocal fold secretions overlying vocal fold epithelium after 1 hour of prolonged voice use. As vocal fold mucosa is the first tissue layer exposed to mechanical stress, allergens, and reflux, and as TNFα reduces cAMP concentration in other tissue, effectors that increase cAMP levels could serve as effective anti-inflammatory agents.

The absence of a significant change in cAMP concentration after exposure to TNFα does not rule out activation of cAMP by inflammatory mediators. The nonsignificant effect could be associated with the exposure duration, dose of inflammatory mediator, or the choice of inflammatory mediator. TNFα was selected because it may be up-regulated after vocal fold inflammation. However, other inflammatory mediators that influence cAMP concentration (e.g., PGE2) are also associated with vocal fold inflammation and may induce more robust changes in cAMP concentration. The effects of other inflammatory cytokines on cAMP concentration and ion transport await further investigation. We selected 30-minute and 2-hour exposure durations to investigate the short-term response to inflammatory perturbations. However, longer exposure durations will also need to be investigated. Although viable vocal fold mucosae were used in all experiments, and experimental manipulations were performed in a warm oxygenated media, it is possible that exposure to the inflammatory mediator in vitro did not trigger some of the signal transduction mechanisms that may be present in vivo. Future studies are needed to investigate the effects of vocal fold inflammation on ion transport in an in vivo model. Furthermore, when compared to human vocal folds, porcine vocal folds have higher levels of hyaluronan, an osmotically active biomolecule, which can influence ion transport. Therefore, the methods reported here will need to be applied to excised fresh cadaver larynges. Gender has not been reported to influence cAMP concentration in other tissues. However, as the biomolecular composition and morphology of male vocal folds are different from female vocal folds, we examined cAMP concentration in both male and female porcine tissue (data not shown). The absence of a significant gender effect confirmed previous research on the nonsignificant interaction between gender and cellular cAMP levels.

CONCLUSIONS

In vitro cAMP assays and electrophysiological techniques were used to demonstrate that constitutive adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin, increased cAMP concentration in porcine vocal fold mucosa and that this increased cAMP concentration was manifested as increased ion transport. We further demonstrated that the increased ion transport was predominantly associated with increased Cl− secretion. Our novel findings contribute to a better understanding of the intracellular mechanisms that underlie vocal fold ion transport. As Cl− secretion is accompanied by water secretion, data from the present study lay the groundwork for pharmacological therapies that increase surface hydration using mechanisms that are intrinsic to the vocal folds.

Acknowledgments

The animals used in this study were provided by support from NIH RR013223 and HL062552 to M. Sturek and the Comparative Medicine Center of IUSM and Purdue University.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Drs. Michael Sturek and Mouhamad Alloosh from the Indiana University School of Medicine for providing the porcine larynges and trachea that were used in this study. We also thank Matt Auman for assistance with preparing tissue for cAMP analysis.

Footnotes

A portion of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Laryngological Association, Combined Otolaryngological Spring Meeting, Orlando, Florida, U.S.A., May 1–2, 2008.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Jiang J, Verdolini K, Aquino B, Ng J, Hanson D. Effects of dehydration on phonation in excised canine larynges. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:568–575. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsiao T, Liu C, Lin K. Videostrobolaryngosocopy of mucus layer during vocal fold vibration in patients with laryngeal tension-fatigue syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:537–541. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiung M. Videolaryngostroboscopic observation of mucus layer during vocal cord vibration in patients with vocal nodules before and after surgery. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:186–191. doi: 10.1080/00016480310014859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato K, Hirano M. Age-related changes in the human laryngeal glands. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107:525–529. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roh J, Kim H, Kim A. The effect of acute xerostomia on vocal function. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;132:542–546. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.5.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanner K, Roy N, Merrill R, Elstad M. The effects of three nebulized osmotic agents in the dry larynx. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50:635–646. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/045). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdolini K, Min Y, Titze IR, et al. Biological mechanisms underlying voice changes due to dehydration. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:268–282. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray SD. Cellular physiology of the vocal folds. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33:679–697. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher K, Telser A, Phillips J, Yeates D. Regulation of vocal fold transepithelial water fluxes. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1401–1411. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lodewyck D, Menco B, Fisher K. Immunolocalization of aquaporins in vocal fold epithelia. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:557–563. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leydon C. PhD dissertation. Evanston: Northwestern University; 2005. Stimulating chloride ion fluxes across vocal fold epithelium. Communication sciences and disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boucher R. Human airway ion transport: part 2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:581–593. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhut M. Changes in ion transport in inflammatory disease. J Inflam. 2006;3:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan C, Sanchez E. Tumor necrosis factor and CD11/CD18 (B2) integrins act synergistically to lower cAMP in human neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2171–2181. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.5.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim X, Tateya I, Tateya T, Munoz-Del-Rio A, Bless D. Immediate inflammatory response and scar formation in wounded vocal folds. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:921–929. doi: 10.1177/000348940611501212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdolini K, Rosen C, Branski R, Hebda P. Shifts in biochemical markers associated with wound healing in laryngeal secretions following phonotrauma: a preliminary study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:1021–1025. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivasankar M, Fisher K. Vocal fold epithelial response to luminal osmotic perturbation. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50:886–898. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/063). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shane M, Nofziger C, Blazer-Yost B. Hormonal regulation of epithelial Na+ channel: from amphibians to mammals. J Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;14:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi Y, Shin T, Sugihara H. Reconstruction of the laryngeal mucosa. A three-dimensional collagen gel matrix culture. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:649–654. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890180057014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn M, Kobler J, Zeitels S, Langer R. Quantitative and comparative studies of the vocal fold extracellular matrix II: collagen. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:225–232. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benninger M, Alessi D, Archer S, et al. Vocal fold scarring: current concepts and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;115:474–482. doi: 10.1177/019459989611500521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford CN. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. JAMA. 2005;294:1534–1540. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston N, Bulmer D, Gill G, et al. Cell biology of laryngeal epithelial defenses in health and disease: further studies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:481–491. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thibeault S, Smith M, Peterson K, Yitalo-Moller R. Gene expression changes of inflammatory mediators in posterior laryngitis due to laryngopharyngeal reflux and evolution with PPI treatment: a preliminary study. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:21–25. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318124a992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lima-Rodrigues M, Valle-Fernandes A, Lamas N, et al. A new model of laryngitis: neuropeptide, cyclooxygenase, and cytokine profile. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:78–86. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181492400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]