Abstract

The fact that action observation, motor imagery and execution are associated with partially overlapping increases in parieto-frontal areas has been interpreted as evidence for reliance of these behaviors on a common system of motor representations. However, studies that include all three conditions within a single paradigm are rare, and consequently, there is a dearth of knowledge concerning the distinct mechanisms involved in these functions. Here we report key differences in neural representations subserving observation, imagery, and synchronous imitation of a repetitive bimanual finger-tapping task using fMRI under conditions in which visual stimulation is carefully controlled. Relative to rest, observation, imagery, and synchronous imitation are all associated with widespread increases in cortical activity. Importantly, when effects of visual stimulation are properly controlled, each of these conditions is found to have its own unique neural signature. Relative to observation or imagery, synchronous imitation shows increased bilateral activity along the central sulcus (extending into precentral and postcentral gyri), in the cerebellum, supplementary motor area (SMA), parietal operculum, and several motor-related subcortical areas. No areas show greater increases for imagery vs. synchronous imitation; however, relative to synchronous imitation, observation is associated with greater increases in caudal SMA activity than synchronous imitation. Compared to observation, imagery increases activation in pre-SMA and left inferior frontal cortex, while no areas show the inverse effect. Region-of-interest (ROI) analyses reveal that areas involved in bimanual open-loop movements respond most to synchronous imitation (primary sensorimotor, classic SMA, and cerebellum), and less vigorously to imagery and observation. The differential activity between conditions suggests an alternative hierarchical model in which these behaviors all rely on partially independent mechanisms.

Keywords: action observation, motor imagery, fMRI, sensorimotor, SMA, cerebellum

Introduction

Evidence for shared and distinct neural representations

Considerable attention has been given to the idea that action observation and motor imagery engage the same neural structures involved in movement execution (Jeannerod, 2001). Support for this view can be found in many previous studies that have examined the neural responses associated with these behaviors in isolation or in pairs (e.g., early PET studies by Stephan et al. (1995) on imagery and execution, Rizzolatti et al. (1996) on observation and execution, and Grafton et al. (1996) on observation and imagery). A widely cited meta-analysis by Grezes and Decety (2001) revealed overlapping foci associated with all three behaviors in supplementary motor area (SMA), dorsal premotor cortex (dPMC), supramarginal gyrus (SMg), and the superior parietal lobe (SPL). For observation and imagery, SMA activation tended to be more rostral, extending into pre-SMA, whereas execution activated more posterior regions, or ‘classic’ SMA (Picard and Strick, 1996). Also, activity in dPMC was more frequently detected in studies of execution than imagery, and in imagery more often than in observation.

Given the obvious differences in these task demands (most notably the lack of movements as well as afferent feedback in observation and imagery), it is indeed remarkable that these behaviors do appear to activate overlapping cortical regions consistently. As detailed shortly, this has been taken as evidence for involvement of a shared set of internal motor representations. The frequency of these statements in the literature, however, belies how few investigations have actually included action observation, imagery and execution conditions within a single paradigm that would allow well-controlled, direct comparisons. In fact, as will be discussed shortly, we know of only one such paper, and it suffers from the confounding effects of using different visual stimuli between conditions (Filimon et al., 2007). As a consequence, we contend that the field lacks a precise and comprehensive understanding of the shared, as well as the potentially unique, neural mechanisms involved in these behaviors. In the current project, we used blood related oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) fMRI to address these issues in a task involving the observation, imagery, and execution of bimanual movements under conditions where visual stimulation was carefully controlled.

Observation vs. Execution

Both behavioral and physiological evidence have been used to argue that similar mechanisms are employed for action observation and execution (Vogt and Thomaschke, 2007). Observation of another person learning novel task dynamics improves subsequent performance on that task (Mattar and Gribble, 2005), whereas performance suffers when executed and observed actions conflict (Kilner et al., 2003). Such demonstrations of motor priming and motor interference, respectively, suggest that common mechanisms are engaged during action observation and execution. In human neuroimaging studies of action observation, the focus has been on identifying shared frontoparietal representations for executed and observed movements that may reflect mechanisms putatively homologous to the mirror neurons detected in the ventral premotor cortex (vPMC) and inferior parietal lobule (IPL) of monkeys (Rizzolatti and Craighero, 2004). Numerous studies of action observation show consistent bilateral increases in posterior parietal and premotor regions that are also engaged during visually-guided movement (Buccino et al., 2001; Frey and Gerry, 2006). Action observation has also been shown to modulate cortical excitability in primary motor cortex (M1) as measured through use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (Clark et al., 2004; Fadiga et al., 1995; Maeda et al., 2001; Strafella and Paus, 2000). Given these results, one might expect that the putative mirror neuron system in humans (inferior frontal gyrus and inferior parietal lobule) would be similarly engaged for passive observation and execution. However, results are mixed. When observation and execution have been directly compared, some investigations find evidence for similar responses in these areas (see summarized in the meta-analysis by Caspers et al. (2010)), yet others report evidence suggesting that the neural representations for these tasks are distinct (Dinstein et al., 2007; Lingnau et al., 2009).

Imagery vs. Execution

As in execution, it has been hypothesized that motor imagery involves the generation of an efferent command that is then inhibited at some level from being overtly executed (Grush, 2004; Jeannerod, 1994). Behavioral studies have shown performance similarities between tasks thought to involve motor imagery and those requiring movement execution (Decety and Jeannerod, 1996; Johnson, 1998, 2000; Sirigu et al., 1995; Sirigu et al., 1996). A growing number of studies have also found that many of the same brain structures involved in performing real movements also show increased activity during imagined movements (Ehrsson et al., 2003; Hanakawa et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2002; Lotze et al., 1999; Nair et al., 2003; Stephan et al., 1995). However, studies that included direct comparisons (Gerardin et al., 2000; Hanakawa et al., 2008; Nair et al., 2003; Stephan et al., 1995) suggest that sensorimotor, premotor, cingulate, and cerebellar regions show greater involvement for execution than for imagery. Depending on the study, imagery appears to place greater demands than execution on left IPL, bilateral dPMC, SMA, prefrontal and subcortical structures (Gerardin et al., 2000), or on dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the inferior frontal (IFg) and middle temporal gyri (MTg) (Stephan et al., 1995). Though always present for execution, results from neuroimaging, regarding the involvement of M1 in motor imagery, are modest at best and vary depending on the tasks and participants (Dechent et al., 2004; Sharma et al., 2008). By contrast, motor imagery, like action observation, has been shown to modulate M1 excitability consistently, as measured through use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (Clark et al., 2004; Fadiga et al., 1999).

To our knowledge, there is but a single published neuroimaging study that included all three conditions in a single paradigm. Using a reaching task, Filimon et al. (2007) found greater increases in activity for execution than for imagery or observation in a variety of regions including sensorimotor cortex, SPL, dPMC, SMg, lingual gyrus, and cuneus. When each was compared against execution separately, increased activity was detected for both observation and imagery in the precuneus, and also for observation vs. execution in the superior occipital lobe. No regions showed more activity for imagery than for observation. However, greater increases in activity were found in superior occipital lobe and middle temporal complex (MT+) for observation vs. imagery. Unfortunately, these findings are hard to interpret because of differences in visual stimulation between conditions. Specifically, visual feedback was available for the execution condition, but not for imagery; in the observation condition the stimulus and actor’s arm were shown in a reduced size.

As a final point, comparisons across neuroimaging studies also are often complicated by differences in visuospatial demands including the perspective from which actions are observed (often 3rd person) vs. imagined or executed (almost exclusively 1st person). No single study has addressed this issue for observation, imagery and execution. Jackson et al. (2006), however, investigated observation and imitation of intransitive actions. They found greater increases in contralateral M1, right MTg, left IFg, and cuneus activation for 1st person perspective and greater increases in lingual gyrus activation for 3rd person perspective across both tasks. Perspective sensitivity has also been found in the SPL for observation and imitation of an object manipulation task (Shmuelof and Zohary, 2008). Another study manipulated perspective by asking participants to imagine themselves (1st-person) or an experimenter (3rd- person) interacting with an object (Ruby and Decety, 2001). They found greater relative increases in left IPL and somatosensory cortex activity for 1st person perspective, and in right IPL, precuneus, and cingulate for 3rd person perspective.

To summarize, evidence for shared neural representations for observation, imagery and execution or imitation is limited. In the present study, we sought to identify similarities and differences in neural activity associated with observation vs. imagery vs. execution when visual stimulation and attention were carefully equated across conditions. Our execution condition is technically synchronous imitation, as participants simultaneously performed the actions along with video of an actor. This should not be mistaken for true imitation, which involves subsequent reproduction of previously viewed actions. On the basis of the data reviewed earlier, we expected the putative mirror neuron system in humans (inferior frontal gyrus and inferior parietal lobule) to show increased activity for both observation and synchronous imitation. Similarly, a common set of regions (including premotor cortex, SMA, posterior parietal cortex (PPC), and potentially primary sensorimotor cortex) were expecteded to show increased activity for both synchronous imitation and imagery. However, given that the motor command and somatosensory feedback were only present for synchronous imitation, we predicted that we might find greater activity in sensorimotor, SMA and cerebellar areas for synchronous imitation than for observation and imagery. Furthermore, synchronous imitation should engage classic SMA, whereas observation and imagery might recruit pre-SMA (Cunnington et al., 2005; Picard and Strick, 1996). We also anticipated that imagery should recruit motor areas to a greater extent than observation because, unlike passive viewing, imagery involves active rehearsal of a motor plan and possibly generation and inhibition of a motor command (Grush, 2004; Jeannerod, 2001).

We also sought to test which of these task manipulations, observation vs. imagery vs. synchronous imitation, provides the most effective means of driving neural activity (and thus potentially plasticity) within regions-of-interest (ROIs: left and right sensorimotor cortex, SMA, and cerebellum) specifically involved in sensorimotor control of bimanual hand movements, as defined by a separate functional localizer task. This was motivated by a desire to better understand the mechanisms underlying recent reports of improved rehabilitation of sensorimotor control through use of motor imagery (Butler and Page, 2006; Page et al., 2007) or action observation (Ertelt et al., 2007).

A secondary exploratory goal of this project was to evaluate whether regions involved in these behaviors exhibit sensitivity to the effects of perspective. This was pursued by manipulating whether participants saw movements from the 1st- or 3rd-person perspective. A similar response across viewpoints would suggest perspective-invariance.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Fourteen healthy, right-handed volunteers (18–36 years, 7 females) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and no history of psychiatric or neurological disease participated. Written informed consent was obtained, and the local ethics committee approved the experimental protocol.

fMRI Design and Procedure

After being given instructions, participants performed a short set of practice trials for 15–20 minutes in a mock MRI scanner. Immediately following this practice, participants moved to the actual scanner. They rested supine on the scanner bed with a cloth draped over their bodies, forearms on thighs, and palms aligned in the vertical plane with thumbs facing up. Padding was placed around the head and upper arms to reduce motion artifacts. Other than performing the instructed hand movements described below, they were told to remain as still as possible. Stimulus presentation and synchronization with the MRI scanner were controlled by a customized program developed with National Instruments LabVIEW software, and using a PCI-1405 image acquisition board. Hand position and movements were recorded with digital video throughout the duration of each run for offline monitoring of task compliance. This allowed us to rule out the presence of overt movements during the imagery or observation conditions, and to ensure that movements were performed as directed during imitation. We cannot, however, guarantee the absence of subthreshold EMG activity during observation and imagery conditions, since it was unable to be measured with our current MRI setup.

The experimental methods are summarized in Figure 1, which shows a partial timeline of the task with representative blocks. Participants performed a sequential bimanual thumb-finger sequencing (TFST) task in synchrony with a 1.5 Hz pacing tone under three conditions: Observe, Imagine, and Imitate (synchronous imitation), while whole-brain data was acquired. These were distinguished by aural presentation of either the word “watch” or “imagine” or “imitate,” respectively, 2s prior to each block. Blocks of each condition lasted 18s and were followed by a 12s rest interval consisting of a black screen. A central fixation circle was always present throughout the entire run. We took great care to ensure that the visual stimulus was carefully controlled: in all conditions, participants viewed the same prerecorded digital video of an actor performing the bimanual TFST in the scanner. In the Observe condition, participants passively viewed the video. In the Imagine condition, participants viewed the video and also imagined moving along with the actor, but physically remained still. In the Imitate condition, participants viewed the video and physically performed the TFST synchronously along with the actor. These manipulations allowed for direct comparison of the networks involved in the different tasks, while holding the observed movement constant.

Figure 1. Illustration of experimental timeline with representative blocks (not all conditions are displayed).

There were 6 conditions in a 3 (task) × 2 (perspective) design. Verbal presentation of the word “Watch” (Observe), “Imagine” (Imagine), or “Imitate” (Imitate) distinguished conditions 2s prior to each block. Observe from the 1st-person perspective and Imagine from the 3rd-person perspective are shown here for illustrative purposes. Fixation circle always present at the center of the screen. Numbers in thought bubbles illustrate participant’s running count of the number of times the fixation changed from red to blue coincident with the pinkie finger contacting the thumb. Finger tapping was sequential and ‘…’ symbols indicate skipped taps for illustration purposes. See Figure 2 for results verifying task compliance measured by this attentional control.

Additionally, we attempted to make the recorded video match what the participants would see if they were viewing their own hands. Both participants and the actor in the video wore gloves. Just before the experiment, participants were shown a semi-transparent digital still frame (1st-person perspective) of the recorded video overlaid on a live video feed of their hands. They were instructed to align their hands with those of the actor and remain in this position throughout the study, so that their hand postures were matched with those of the actor depicted in the recorded video. Participants were told to observe, imagine, or execute the task along with the actor, which always began with the index finger, and was preceded by two preparatory tones to facilitate temporal correspondence. In the instructions for the imagine task, we emphasized that participants should really try to feel themselves moving without physically moving.

The orientation of the visual stimuli was also manipulated. Within all three conditions, 50% of counterbalanced blocks presented visual stimuli from the perspective of the participant (1st-person perspective), and the remaining 50% were rotated by 180° (3rd-person perspective).

Participants completed four (8.6 min) runs. Each run consisted of 2 blocks of each of the six conditions (3 types (Observe, Imagine, Imitate) × 2 perspectives (1st-person, 3rd-person)). A control condition where live feedback was given during Imitate trials was also included as part of the block design and was included within the counterbalanced order of each run, but is discussed elsewhere (Macuga and Frey, 2011). Condition order was counterbalanced across runs, and the 4 runs were counterbalanced across participants.

Orienting Task

To control for possible variations in attention across conditions, participants performed a secondary task that required counting features of the observed movements. The color of the fixation circle at the center of the screen changed periodically from red to blue. For each run, participants were asked to track these changes and verbally report the total number of times that the color changed from red to blue coincident with the pinkie finger contacting the thumb. On average, this occurred on 25% of the pinkie taps, but the actual number ranged from 18–30 times per run. Within each block, however, the circle had an equal probability of changing. Participants reported cumulative values at the end of each run. The change occurred with equal likelihood during each condition. We consider this a novel improvement in experimental design for this area of research, since previous studies have not attempted to control for variations in attention across conditions. However, we acknowledge that this does make the task more demanding.

Sensorimotor localizer

Participants performed a single run of the aurally paced TFST task described above with their eyes closed, in order to functionally define sensory and motor areas involved in executing bimanual hand movements. The verbal commands “move,” or “rest” and a 1.5Hz pacing tone were presented with Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc. v. 10.0, Albany, CA; http://www.neurobs.com) and digitally synchronized with the scanner. This task was performed after the main experiment. A simple contrast of the move vs. rest conditions was used to identify and define four regions of interest: left sensorimotor hand area, right sensorimotor hand area, cerebellum, and SMA.

Data acquisition

Scans were performed on a Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) 3T Allegra MRI scanner. BOLD echoplanar images (EPIs) were collected using a T2*-weighted gradient echo sequence, a standard birdcage radio-frequency coil, and the following parameters: TR = 2000ms, TE = 30ms, flip angle = 90°, 64 × 64 voxel matrix, FoV = 220mm, 34 contiguous axial slices acquired in interleaved order, thickness = 4.0mm, in-plane resolution: 3.4 × 3.4 mm, bandwidth = 2790 Hz/pixel. The initial four scans in each run were discarded to allow the MR signal to approach a steady state. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were also acquired, using the 3D MP-RAGE pulse sequence: TR = 2500ms, TE = 4.38ms, TI = 1100ms, flip angle = 8.0°, 256 × 256 voxel matrix, FoV = 256mm, 176 contiguous axial slices, thickness = 1.0mm, in-plane resolution: 1.0 × 1.0 mm. DICOM image files were converted to NIFTI format using MRIConvert software (http://lcni.uoregon.edu/~jolinda/MRIConvert/).

Preprocessing

Structural and functional fMRI data from both the localizer and main task were preprocessed and analyzed using fMRIB’s Software Library [FSL v.4.1.2 (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/)] (Smith et al., 2004) and involved several steps: motion correction using MCFLIRT, independent components analysis conducted with MELODIC to identify and remove any remaining obvious motion artifacts, fieldmap-based EPI unwarping to correct for distortions due to magnetic field inhomogeneities using PRELUDE+FUGUE (with a separate fieldmap collected following each functional run), non-brain matter removed using BET, data spatially smoothed using a 5mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel, mean-based intensity normalization applied, in which each volume in the data set is scaled by the same factor, to allow for cross-sessions and cross-subjects statistics to be valid, high-pass temporal filtering with a 100s cut-off was used to remove low-frequency artifacts, time-series statistical analysis was carried out in FEAT v.5.98 using FILM with local autocorrelation correction, delays and undershoots in the hemodynamic response accounted for by convolving the model with a double-gamma HRF function, registration to the high-resolution structural with 7 degrees of freedom and then to the standard images with 12 degrees of freedom (Montreal Neurological Institute [MNI-152] template) at a 2 × 2 × 2 voxel resolution implemented using FLIRT, and registration from high resolution structural to standard space was performed with FNIRT nonlinear registration (Andersson et al., 2007).

Whole brain Analysis

For every participant, each of the four fMRI runs containing Observe, Imagine, and Imitate conditions viewed from either a 1st- or 3rd-person perspective, were modeled separately at the first level. Orthogonal contrasts (one-tailed t-tests) were used to test for differences between each of the experimental conditions and resting baseline. Orthogonal contrasts were also used to test for differences between conditions. Because, as will be detailed, the only differences for contrasts of the 1st- vs. 3rd-person perspectives were in occipital visual areas, we collapsed across perspective.

The resulting first-level contrasts of parameter estimates (COPEs) then served as inputs to higher-level analyses carried out using FLAME Stage 1 to model and estimate random-effects components of mixed-effects variance. Z (Gaussianized T) statistic images were thresholded using a cluster-based threshold of Z > 3.1 and a whole-brain corrected cluster significance threshold of p = 0.05. First-level COPEs were averaged across the 4 runs for each subject separately (level 2), and then averaged across participants (level 3). For the group-level analysis, FEAT uses FMRIB’s Local Analysis of Mixed Effects (FLAME) to estimate the random-effects component of the measured inter-subject mixed-effects variance, using Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling to get an accurate estimation of the true random-effects variance and degrees of freedom at each voxel.

To determine areas of common activation across conditions, a conjunction analysis was conducted (Nichols et al., 2005). Group statistical activations for each of the three conditions vs. rest were thresholded individually (Z = 3.1, p < .05 clusterwise corrected for multiple comparions), binarized, and multiplied, resulting in a conjunction that reveals brain areas activated by observation AND imagery AND execution.

Anatomical localization of brain activation was verified by manual comparison with an atlas (Duvernoy, 1991). In addition, the multi-fiducial mapping alogorithm in Caret (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/caret/) (Van Essen et al., 2001) was used to overlay group statistical maps onto a population-average, landmark- and surface-based (PALS) atlas for visualization (Van Essen, 2005).

ROI Analysis

ROI analyses were conducted on the four areas showing significant increases in activity during the hand movement vs. rest comparison in the sensorimotor localizer task: left sensorimotor hand area, right sensorimotor hand area, SMA, and bilateral cerebellum.

Mean percent signal change, relative to the resting baseline, was calculated separately across all voxels within every functionally defined ROI for each participant and condition using FSL’s Featquery. Repeated-measures 3 (task: observation, imagery, imitation) × 2 (perspective: 1st vs. 3rd person) ANOVAS were conducted to test for mean percent signal change differences between conditions within these ROIs. For post-hoc pairwise comparisons, SPSS Bonferroni adjusted p-values were used.

Results and Discussion

Behavioral Results from Orienting Task

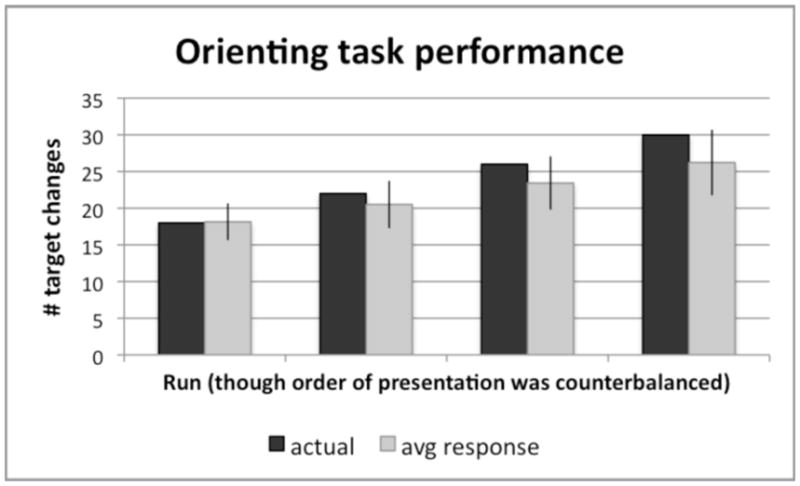

Figure 2 shows the results for the orienting task designed to equate attention across all conditions. Participants performed this somewhat difficult task with a mean of 88% accuracy, indicating that they were attending to the viewed movements. On average, however, they tended to underestimate the actual number of times target events occurred in a given run, t (55) = 6.83, p < .001, mean difference = −2.8).

Figure 2. Behavioral results for orienting task designed to control for variations in attention across conditions.

Note that the ordering of runs on the x-axis by number of target changes is done for the purpose of analysis, but does not reflect the actual order of presentation. The run order was counterbalanced across participants. The y-axis refers to the number of fixation changes that occurred during pinkie taps, that participants had to report after completing each run. Mean performance = 88% accuracy, but participants generally underestimated the actual number of fixation color changes during pinkie taps by a mean difference of −2.8, t(55) = 6.83, p < .001, and this underestimation was amplified as the actual number of changes increased.

fMRI Results

Similarities and differences in neural activity associated with observation, imagery, and synchronous imitation

Conjunction for Observation vs. Rest, Imagery vs. Rest, and Imitate vs. Rest contrasts

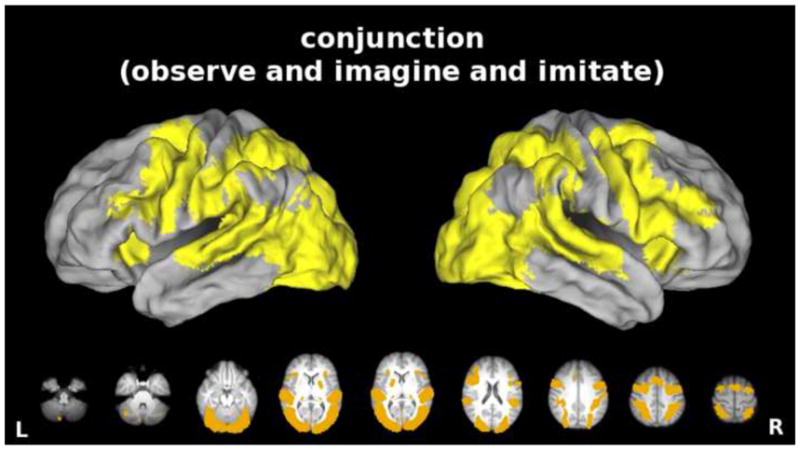

Figure 3 shows all voxels exhibiting significant increases in activity relative to resting baseline for observation, imagery, AND synchronous imitation. Consistent with the hypothesis that these behaviors draw on common mechanisms (Caspers et al., 2010; Grezes and Decety, 2001), the conjunction shows that all three conditions were associated with increased bilateral increases in activity within a common set of frontal (premotor, pre-SMA), posterior parietal, superior temporal and primary sensorimotor areas, as well as subcortical (thalamus, putamen) regions traditionally implicated in visually-guided bimanual behavior. These similarities could be partly, or entirely, due to perceptual processing of the same visual stimuli across conditions, however. To address this possibility, we next performed pairwise contrasts between specific conditions matched for visual stimulation.

Figure 3. Conjunction.

Common areas of significantly increased activity (vs. resting baseline) for the Observe, the Imagine, AND the Imitate conditions. Here, and in all subsequent figures, we refer to synchronous imitation as “imitation.” Note expected overlap in bilateral frontal (premotor, pre-SMA), posterior parietal, superior temporal and primary sensorimotor areas, as well as subcortical (thalamus, putamen) areas often detected in previous studies of action observation, imagery, and/or execution. Data here and in subsequent figures are displayed on a partially inflated view of CARET’s population-average, landmark- and surface-based (PALS) human brain atlas (ref) (see Methods). Likewise, data in the lower portion of each panel are rendered on axial slices from the group average anatomical image and oriented neurologically.

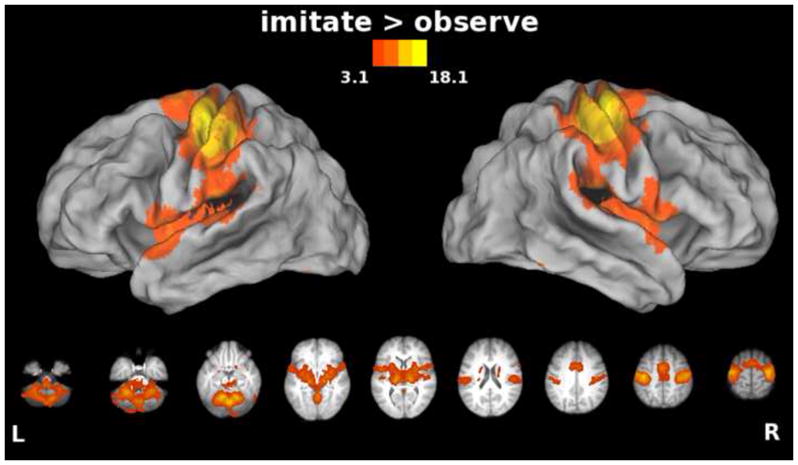

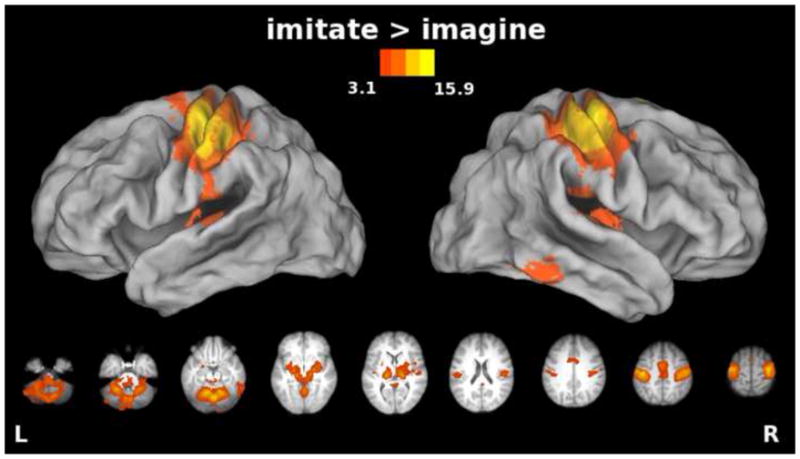

Imitation vs. Observation

We hypothesized that there would be increased engagement of primary sensorimotor cortices and cerebellum for synchronous imitation (Filimon et al., 2007). When an action is executed, an efferent command is issued and somatosensory feedback provides information about the state of the moving fingers. In the case of passive observation, these signals are unchanging because the fingers are held still. As expected, greater increases in activity were seen bilaterally in sensorimotor cortices (along the central sulcus extending into precentral and postcentral gyri), and in the cerebellum when the movements were physically executed compared to when they were observed (Figure 4, imitation vs. observation). SMA and parietal operculum (putative secondary somatosensory cortex), as well as subcortical structures (putamen, thalamus, and basal ganglia) were also more active for synchronous imitation than for observation. Consistent with evidence for a rostrocaudal functional division of SMA, activation for synchronous imitation was more posterior (SMA) than activation for observation (pre-SMA) (Picard and Strick, 1996). Because the visual stimulus is the same for both conditions, these differences cannot be attributed to this source.

Figure 4. Areas showing increased activity for the Imitate vs. Observe comparison.

In this and subsequent figures, group statistical parametric maps were thresholded at Z>3.1 (corrected clusterwise significance threshold p<0.05). Bilateral precentral and postcentral gyri, cerebellum, SMA, and insula extending into parietal operculum, as well as subcortical structures such as putamen, thalamus, and basal ganglia showed greater responses during imitation vs. observation of actions.

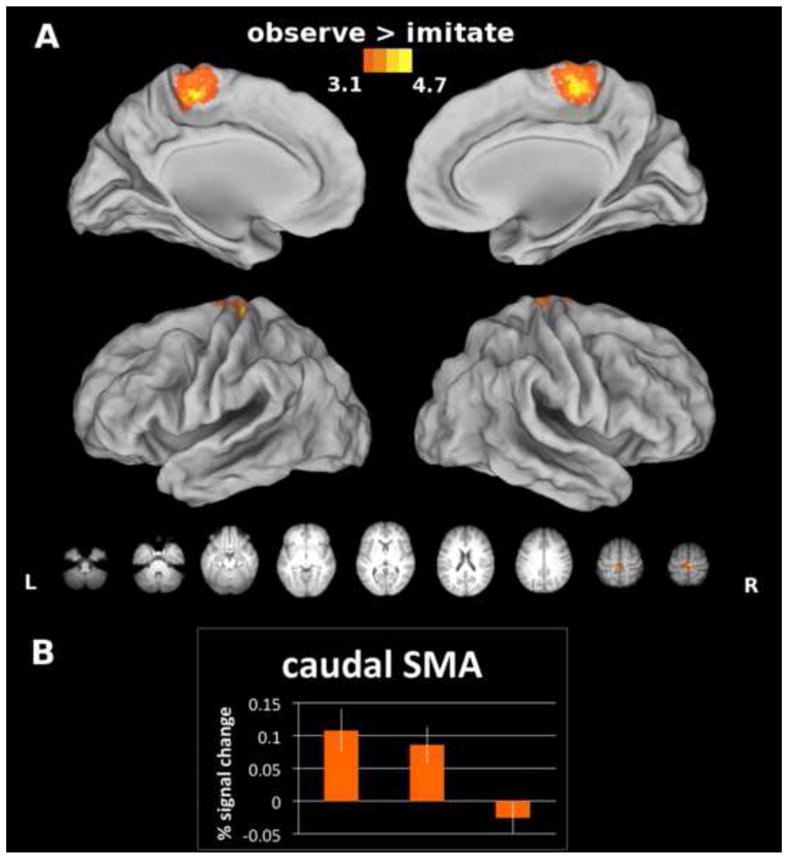

Unexpectedly, we found a single focal region in caudal SMA that showed greater increases in activity for observation vs. imitation (Figure 5, panel A). When we calculated the mean percent signal change for each condition (Figure 5, panel B), this area showed increased activity relative to baseline for both observation (p < .01) and imagery (p < .01), but not for synchronous imitation (p = .34). A follow-up exploratory ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition (F(2,26) = 13.48; p < .001), and in Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests, observation (p < .01) and imagery (p < .01) both showed significantly greater increases in activity than imitation, but did not significantly differ from each other. Using dynamic causal modeling, Kasess et al. (2008) have suggested that SMA suppresses M1 to restrain movement execution during motor imagery. Similarly, Dinomais et al. (2009) found greater increases in SMA activity for passive vs. active video-guided movements, highlighting the role of SMA in inhibiting movements elicited by observation of the moving hand. It seems plausible here that caudal SMA might be providing an inhibitory signal to dampen M1 activity during observation and imagery in order to prevent unwanted movements.

Figure 5. A) Area showing increased activity for the Observe vs. Imitate comparison and B) the calculated mean percent signal change for all 3 conditions in this region.

The caudal-most sector of SMA was activated to a significantly greater extent during observation vs. synchronous imitation of actions. We probed this unexpected finding further to make sure that it was not the result of a deactivation in one or more conditions. Instead, we found that in this region, observation and imagery show increases in activation that are significantly greater than synchronous imitation, which does not differ from the resting baseline. Bars represent standard errors.

Imitation vs. Imagery

Like synchronous imitation, imagery might involve formation of the efferent motor command, though the motor command itself must be inhibited before reaching the muscles (Jeannerod, 1995), and afferent sensory feedback is unchanging since there is no actual movement. These facts predict that activity in primary sensorimotor cortices should be greater for synchronous imitation than for imagery. Consistent with this and with previous findings (Filimon et al., 2007; Gerardin et al., 2000; Nair et al., 2003; Stephan et al., 1995), we found greater increases in activity for imitation vs. imagery bilaterally along the central sulcus (extending into precentral and postcentral gyri) and in the cerebellum (Figure 6). These are similar to the results for imitation vs. observation in the previous section, and are likely due to the fact that neither imagery nor observation involve issuing the descending efferent command or receiving sensory feedback. Likewise, we again see more caudal SMA increases in activation for imitation vs. imagery. We return to these findings later in the ROI analysis section. Parietal operculum (putative secondary somatosensory cortex), as well as movement-related subcortical structures (putamen, thalamus, and basal ganglia), were also more active during imitation than imagery.

Figure 6. Areas showing increased activity for the Imitate vs. Imagine comparison.

Bilateral precentral and postcentral gyri, cerebellum, SMA, and insula extending into parietal operculum, as well as subcortical structures such as putamen, thalamus, and basal ganglia showed greater responses for imitation vs. imagery of actions.

Based on previous results (Gerardin et al., 2000), we expected that imagery might be associated with greater increases in left IPL, bilateral dPMC. SMA, prefrontal and subcortical structures or on dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), IFg, or MTg (Stephan et al., 1995) than synchronous imitation. However, the imagery vs. imitation contrast revealed no significant differences in activity. This suggests that in the present bimanual task, the areas involved in motor imagery are a subset of those involved in synchronous imitation. It is possible that for more cognitively demanding or complex imagery tasks, other areas might also be recruited.

In sum, our results for imitation vs. observation or vs. imagery are similar to those of Filimon et al. (2007) with regard to increased activity in precentral and postcentral gyri. However, because our task was bimanual, our effects were bilateral rather than left-lateralized. We did not, however, find increased activity in SPL, or in visual areas - lingual gyrus and cuneus. The failure to detect these differences is most likely due to the fact that visual stimuli were identical across our conditions. A similar explanation might apply to differences between imagery vs. execution that were detected by Filimon et al. (2007), but not in the current investigation.

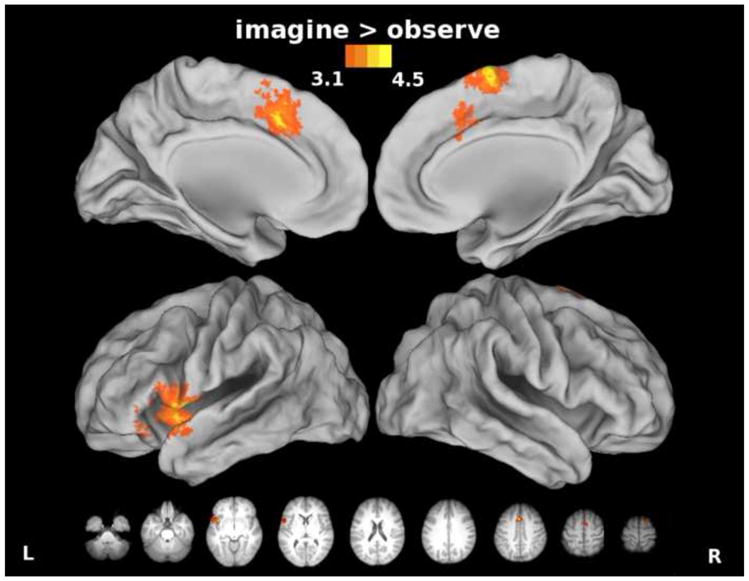

Imagine vs. Observe contrast

Given that imagery involves active rehearsal of a motor plan and possibly generation and inhibition of a motor command (Grush, 2004; Jeannerod, 2001), we hypothesized that imagery should recruit motor regions to a greater extent than observation. We found that imagery of movements produced greater increases in activity in pre-SMA than observation of movements (Figure 7). It has been suggested that an efference copy may be generated in SMA (Haggard and Whitford, 2004), because TMS over this region removes the sensory suppression effect for voluntary movements. Though the motor command is not physically executed for imagery, an efference copy could be generated and utilized in service of motor imagery (Grush, 2004). Alternatively, go/no-go experiments suggest that pre-SMA may play a role in motor response inhibition (Mostofsky et al., 2003; Sharp et al., 2010), and the need to inhibit movement execution during imagery may explain the increase here. Although the imagined actions were bilateral, we found greater increases within the motor-dominant left hemisphere in IFg and insula, and anterior cingulate gyrus for imagery than for observation (Figure 7). Conversely, no areas showed greater activation for observation than for imagery. Such differences are not surprising because imagery involved the very same visual stimuli as observation, but in addition required participants to mentally simulate movement. In other words, as imagery increases activity within a subset of areas engaged by synchronous imitation, so too does observation increase activity within a subset of regions engaged during motor imagery. Here we utilized passive observation, though we acknowledge that tasks involving observational learning could produce different results. It has been shown that passive observation and observation with the intent to later reproduce an action activate the same regions, though such activity is increased when the action must later be reproduced (Frey and Gerry, 2006).

Figure 7. Areas showing increased activity for the Imagine vs. Observe comparison.

Pre-SMA, cingulate, insula, and left inferior frontal cortex were activated to a significantly greater extent during imagery vs. observation of actions.

Other studies that included observation and imagery conditions in the same paradigm either did not contrast them (Grafton et al., 1996), or compared the results of motor imagery performed without vision of the hand to those detected in observation (Filimon et al., 2007). With uncontrolled visual stimulation, the latter study did not detect any areas that showed greater increases in activity for imagery vs. observation. They only found differences for observation vs. imagery in visual movement areas (superior occipital lobe, MT+), which seems likely to be a result of their experimental design; specifically, their subjects saw an arm moving in the observation condition, but only a target object in the imagery condition. Here, the visual stimuli were identical, so that the only difference between the observation and the imagery conditions was the kinesthetic imagery component. Guillot et al. (2009) have shown that kinesthetic imagery produces greater increases in SMA, IFg, cingulate, and cerebellar activations than visual imagery. Our results are consistent with this finding.

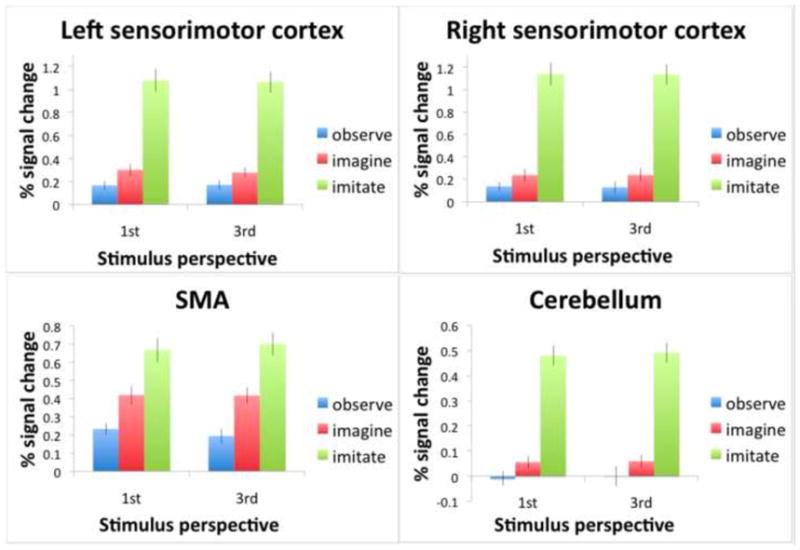

Region of Interest Analyses

Activity in regions of interest

A key test of the hypothesis that action observation, imagery and execution all rely on common motor representations is whether these conditions engage regions involved in the control of bimanual movements: sensorimotor hand areas, SMA, and cerebellum. Indeed, activity associated with the Observe, Imagine, and Imitate conditions exceeded that of the resting baseline in left and right sensorimotor and SMA ROIs (p < .01; Figure 8, panels A, B, and C). These areas were not equally stimulated by the three conditions, however, which is discussed in the results for each ROI below. For the cerebellum, activity for the Imagine (p < .01) and Imitate (p < .05), but not the Observe, condition (p >.05) exceeded the resting baseline (Figure 8, panel D).

Figure 8. Percent signal change from the resting baseline within four ROIs: A) left sensorimotor, B) right sensorimotor, C) SMA, and D) cerebellum, shown for all experimental conditions.

These were identified by the sensorimotor localizer for execution of the TFST without vision. Bars represent standard errors. All conditions showed activations higher than the resting baseline, with the exception of the observation condition in the cerebellum. Synchronous imitation resulted in greater activity than observation for all ROIs. Imagery and observation showed similar activations in left and right sensorimotor areas, although there was also a marginally significant difference between imagery and observation on the left side. However, in SMA and cerebellum, imagery showed higher activations compared to observation.

Within each ROI, there was a main effect of condition, but no effect of visual perspective or interaction. Therefore, the following analyses collapsed across perspective and focused only on condition. Pairwise comparisons were Bonferroni corrected.

Left and right sensorimotor hand representations

For left (F(2,26) = 75.91; p < .001) and right (F(2,26) = 63.55; p < .001) sensorimotor cortices, synchronous imitation resulted in greater activity than observation or imagery, (p < .001 for all). This echoed the results from the whole brain analysis in showing that observation and imagery are not driving the sensorimotor cortex as robustly as real movement. Previous fMRI evidence that motor imagery involves primary sensorimotor representations has been variable (Dechent et al., 2004; Sharma et al., 2008). However, by conducting more sensitive ROI analyses based on an independent localizer, we have detected these effects in the hand representations. The fact that we did see some increases in sensorimotor hand area activity for imagery (Clark et al., 2004; Fadiga et al., 1999) and observation (Fadiga et al., 1995; Maeda et al., 2001; Strafella and Paus, 2000) is also consistent with previous TMS results. We also found a significant difference between imagery and observation for the motor-dominant left sensorimotor cortex (p = .047). This is consistent with reports of left hemisphere dominance for motor imagery tasks (Johnson et al., 2001; Sabate, 2004).

SMA

Differences between all three conditions were significant (p < .05) for SMA (F(2,26) = 34.40; p < .001) with synchronous imitation showing greater increases in activity than imagery and imagery showing greater increases in activity than observation (Figure 8). As we hypothesized, based on prior suggestions that an efference copy is generated for imagined actions (Grush, 2004; Jeannerod, 1994), imagery was in fact recruiting this motor area to a greater extent than passive observation. This SMA ROI appears to be functionally different from the more caudal sector of SMA that showed greater increases for observation vs. imitation (Figure 5).

Cerebellum

Differences between all three conditions were also significant for the cerebellum, (F(2,26) = 93.93; p < .001), with synchronous imitation again showing greater increases in activity than imagery, and imagery showing greater increases than observation. As noted earlier, cerebellar responses associated with observation did not in fact differ significantly from rest. This suggests that it might be necessary to compute a motor command (and perhaps an efference copy), through either movement execution or imagery, in order to engage the cerebellum. Actual movement and accompanying feedback, however, does not seem to be critical, given the increase detected in the imagery condition. In fact, injury to the cerebellum can cause motor imagery deficiencies (Battaglia et al., 2006; Gonzalez et al., 2005; Grealy and Lee, 2011). It has been suggested that during imagery, the brain internally simulates the predicted sensory consequences of a movement via a forward model (Grush, 2004), and the cerebellum seems well suited to support this function (Miall and King, 2008; Wolpert et al., 1998). However, this would require these models being used to generate much longer-range forecasts of likely sensory feedback than has been conventionally assumed by existing models of sensorimotor control, and more work is needed to evaluate this possibility (Frey, 2010).

In summary, we found evidence that motor imagery and action observation increase activity in ROIs that are involved in synchronous imitation, but to a lesser degree. In sensorimotor hand areas, activity was greatest for synchronous imitation followed by imagery and observation. In the SMA, a similar pattern was observed, except that the effects of imagery were significantly greater than those associated with observation. Synchronous imitation and imagery also had a significant effect on cerebellar activity, but observation did not. As will be discussed, these findings are consistent with results from the whole brain analyses in suggesting a hierarchical organization of neural representations underlying motor execution, motor imagery and action observation.

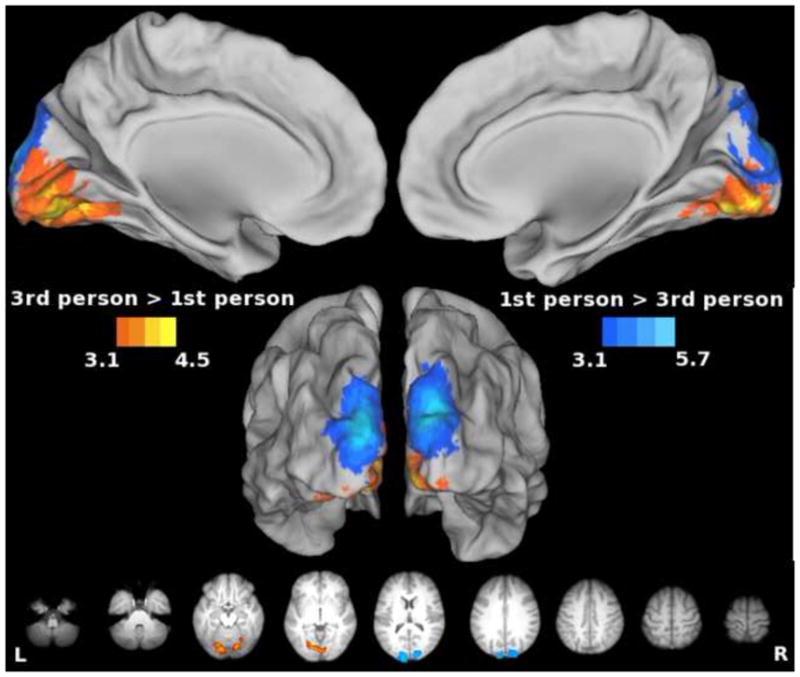

Visual Perspective (1st- vs. 3rd-person)

Increased activity for the 1st- vs. 3rd-person perspective was detected inferior to the calcarine fissure (Figure 9, cool colors), while the opposite contrast revealed effects superior to the calcarine fissure (Figure 9, warm colors). Others similarly found increased cuneus activation for 1st person perspective and increased lingual gyrus activation for the 3rd person perspective during observation and imitation of intransitive actions (Jackson et al., 2006). These effects are likely attributable to differential stimulation of the lower visual field (in which 1st-person perspective stimuli appeared), or the upper visual field (in which 3rd-person perspective stimuli appeared), as shown in the partial timeline from Figure 1. To conclude, the only differences in activation that were revealed by the manipulation of visual perspective across conditions were located in occipital cortex, suggesting perspective invariance in all other regions. However, it may be the case that both view-dependent and perspective-invariant neurons exist within these areas, and cannot be distinguished with fMRI. Using single cell recording, Caggiano (2011) recently found view-invariant as well as view-dependent cells in monkey F5.

Figure 9. Effect of stimulus perspective only in occipital cortex.

Data were averaged across Observe, Imagine, and Imitate conditions. Warm colors denote areas more active for 3rd- vs. 1st-person perspective. Cool colors denote areas more active for the 1st- vs. 3rd-person perspective. Effects of the visual perspective manipulation were only seen in occipital areas. As would be expected, the upper visual field (where 3rd person perspective stimulus was displayed) is represented below the calcarine sulcus, and the lower visual field (where 1st person perspective was displayed) is represented. Regions identified by the sensorimotor localizer, however, were perspective invariant.

Summary & Conclusion

Claims are frequently advanced that common neural mechanisms underlie action observation, imagery, and execution (Jeannerod, 1994; Prinz, 1997). However, direct tests of this hypothesis have suffered from a failure to include all three conditions in a single paradigm, or from incomplete control over visual stimuli between tasks (Filimon et al., 2007). The current project addressed these limitations by including observation, imagery and execution of the same bimanual action under conditions in which visual stimulation was held constant and attentional factors were controlled. Whole brain analyses revealed only partial support for the hypothesis that observation or imagery of an action engages the same neural representations involved in execution of the same action. Widespread cortical (premotor, pre-SMA, posterior parietal, superior temporal and primary sensorimotor areas), as well as subcortical (thalamus, putamen) regions involved in sensorimotor control showed increased activity for the conjunction across all three conditions. However, these responses may be partly, or entirely, attributed to common visual stimulation across conditions, performance of the orienting task, and/or other demands (e.g., attentional, higher-level action processing) shared by these tasks. This was addressed through direct, pairwise comparisons, which revealed important differences in activity between these conditions.

Hierarchical Organization of Neural Representations for Observation, Imagery and Imitation

Our findings are generally consistent with a hierarchy in which areas showing increased activity during observation are a subset of those engaged during motor imagery, which in turn are a subset of those engaged during synchronous imitation. Synchronous imitation resulted in greater increases than either imagery or observation in bilateral sensorimotor cortex, cerebellum, classic SMA, parietal operculum (putative secondary somatosensory cortex), and in several motor-related subcortical areas. These differences likely reflect processing of the descending efferent signal and afferent feedback. Relative to observation, motor imagery produced increased activation in pre-SMA, cingulate, anterior insula, and left inferior frontal cortex. The one exception to this hierarchical ordering is a selective increase in caudalmost SMA that is greater for observation and imagery than synchronous imitation. This unexpected finding is inconsistent with the notion of a rostral-to-caudal gradient of abstraction in motor representations within the medial motor areas (Picard and Strick, 1996) and will be a topic of future research.

Furthermore, we selectively isolated regions involved in bimanual hand actions with an independent sensorimotor localizer and then assessed how each task modulated activity within four functionally-defined ROIs. These results too are generally consistent with the notion of hierarchy. With the exception of observation in the cerebellum, we find that all three conditions were associated with significant increases in activity relative to resting baseline. Execution-related responses were signficantly greater than those of imagery or observation in all areas, and the effects of imagery exceeded those of observation in classic SMA and cerebellum.

In conclusion, when conditions are equated for visual stimulation, observation and imagery activate a subset of the areas required for movement execution, and to a lesser extent. Both imagery and observation can increase activity in primary sensorimotor hand representations, however actively simulating movements via imagery stimulates pre-SMA, cingulate, insula, and left IFg more than passive observation does. Imagery thus provides a more effective means of driving neural activity in these areas of the sensorimotor network. This suggests that imagery might be a more effective tool for stimulating these particular brain regions than passive observation for purposes of rehabilitation (Mulder, 2007) or for controlling brain-machine interfaces (Kamousi et al., 2005). Imagery has previously been shown to improve motor function in stroke patients, though the neural mechanisms were not examined (Butler and Page, 2006; Page et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2006). Knowing which parts of this sensorimotor network are distinct and which are overlapping has important implications regarding the use of observation and imagery as proxies for execution.

Highlights.

Compared neural representations for observation, imagery, and imitation with fMRI

Controlled visual stimulation reveals a hierarchical organization

Imitation > imagery or observation in sensorimotor cortex, SMA and cerebellum

Imagery > observation in pre-SMA, cerebellum, left IFg, insula, and cingulate gyrus

Observation > imitation in caudalmost SMA

Acknowledgments

We thank helpful input from anonymous reviewers, and Bill Troyer for his contributions to the LabVIEW software development. Grants from USAMRAA (06046002) and NIH/NINDS (NS053962) to S.H.F. supported this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. Non-linear optimisation. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Buccino G, Binkofski F, Fink GR, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Gallese V, Seitz RJ, Zilles K, Rizzolatti G, Freund HJ. Action observation activates premotor and parietal areas in a somatotopic manner: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:400–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AJ, Page SJ. Mental practice with motor imagery: evidence for motor recovery and cortical reorganization after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:S2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano V, Fogassi L, Rizzolatti G, Pomper JK, Thier P, Giese MA, Casile A. View-based encoding of actions in mirror neurons of area f5 in macaque premotor cortex. Curr Biol. 2011;21:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Zilles K, Laird A, Eickhoff S. ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1148–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Tremblay F, Ste-Marie D. Differential modulation of corticospinal excitability during observation, mental imagery and imitation of hand actions. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnington R, Windischberger C, Moser E. Premovement activity of the pre-supplementary motor area and the readiness for action: studies of time-resolved event-related functional MRI. Hum Mov Sci. 2005;24:644–656. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Jeannerod M. Mentally simulated movements in virtual reality: does Fitts’s law hold in motor imagery? Behav Brain Res. 1996;72:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechent P, Merboldt KD, Frahm J. Is the human primary motor cortex involved in motor imagery? Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;19:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinomais M, Minassian AT, Tuilier T, Delion M, Wilke M, N’Guyen S, Richard I, Aubé C, Menei P. Functional MRI comparison of passive and active movement: possible inhibitory role of supplementary motor area. Neuroreport. 2009;20:1351–1355. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328330cd43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinstein I, Hasson U, Rubin N, Heeger DJ. Brain areas selective for both observed and executed movements. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:1415–1427. doi: 10.1152/jn.00238.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy HM. The human brain: surface, blood supply, and three-dimensional sectional anatomy. 2. Springer Wien; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrsson HH, Geyer S, Naito E. Imagery of voluntary movement of fingers, toes, and tongue activates corresponding body-part-specific motor representations. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3304–3316. doi: 10.1152/jn.01113.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertelt D, Small S, Solodkin A, Dettmers C, McNamara A, Binkofski F, Buccino G. Action observation has a positive impact on rehabilitation of motor deficits after stroke. NeuroImage. 2007;36:T164–T173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadiga L, Buccino G, Craighero L, Fogassi L, Gallese V, Pavesi G. Corticospinal excitability is specifically modulated by motor imagery: a magnetic stimulation study. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Pavesi G, Rizzolatti G. Motor facilitation during action observation: a magnetic stimulation study. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:2608–2611. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filimon F, Nelson J, Hagler D, Sereno M. Human cortical representations for reaching: Mirror neurons for execution, observation, and imagery. NeuroImage. 2007;37:1315–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey SH. Forecasting the long-range consequences of manual and tool use actions: neurophysiological, behavioral and computational considerations. In: Danion FMLE, editor. Motor control: Theories, experiments and applications. Oxford; New York: 2010. pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Frey SH, Gerry VE. Modulation of neural activity during observational learning of actions and their sequential orders. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13194–13201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3914-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardin E, Sirigu A, Lehericy S, Poline JB, Gaymard B, Marsault C, Agid Y, Le Bihan D. Partially overlapping neural networks for real and imagined hand movements. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:1093–1104. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.11.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton ST, Arbib MA, Fadiga L, Rizzolatti G. Localization of grasp representations in humans by positron emission tomography. 2. Observation compared with imagination. Exp Brain Res. 1996;112:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00227183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grezes J, Decety J. Functional anatomy of execution, mental simulation, observation, and verb generation of actions: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;12:1–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200101)12:1<1::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grush R. The emulation theory of representation: motor control, imagery, and perception. Behav Brain Sci. 2004;27:377–396. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x04000093. discussion 396–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot A, Collet C, Nguyen VA, Malouin F, Richards C, Doyon J. Brain activity during visual versus kinesthetic imagery: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2157–2172. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Whitford B. Supplementary motor area provides an efferent signal for sensory suppression. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;19:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanakawa T, Dimyan M, Hallett M. Motor Planning, Imagery, and Execution in the Distributed Motor Network: A Time-Course Study with Functional MRI. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:2775–2788. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanakawa T, Immisch I, Toma K, Dimyan M, Van Gelderen P, Hallett M. Functional properties of brain areas associated with motor execution and imagery. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:989–1002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00132.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P, Meltzoff A, Decety J. Neural circuits involved in imitation and perspective-taking. NeuroImage. 2006;31:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. The representing brain: neural correlates of motor intention and imagery. Brain and Behavioral Sciences. 1994;17:187–245. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. Mental imagery in the motor context. Neuropsychologia. 1995;33:1419–1432. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00073-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. Neuroimage. 2001;14:S103–109. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SH. Cerebral organization of motor imagery: contralateral control of grip selection in mentally represented prehension. Psychological Science. 1998;9:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SH. Imagining the impossible: intact motor representations in hemiplegics. Neuroreport. 2000;11:729–732. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200003200-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SH, Corballis PM, Gazzaniga MS. Within grasp but out of reach: evidence for a double dissociation between imagined hand and arm movements in the left cerebral hemisphere. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:36–50. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SH, Rotte M, Grafton ST, Hinrichs H, Gazzaniga MS, Heinze HJ. Selective activation of a parietofrontal circuit during implicitly imagined prehension. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1693–1704. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamousi B, Liu Z, He B. Classification of motor imagery tasks for brain-computer interface applications by means of two equivalent dipoles analysis. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2005;13:166–171. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.847386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasess CH, Windischberger C, Cunnington R, Lanzenberger R, Pezawas L, Moser E. The suppressive influence of SMA on M1 in motor imagery revealed by fMRI and dynamic causal modeling. Neuroimage. 2008;40:828–837. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilner JM, Paulignan Y, Blakemore SJ. An interference effect of observed biological movement on action. Curr Biol. 2003;13:522–525. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingnau A, Gesierich B, Caramazza A. Asymmetric fMRI adaptation reveals no evidence for mirror neurons in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:9925–9930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902262106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze M, Montoya P, Erb M, Hulsmann E, Flor H, Klose U, Birbaumer N, Grodd W. Activation of cortical and cerebellar motor areas during executed and imagined hand movements: an fMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 1999;11:491–501. doi: 10.1162/089892999563553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macuga KL, Frey SH. Selective responses in right inferior frontal and supramarginal gyri differentiate between observed movements of oneself vs. another. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda F, Chang V, Mazziotta J, Iacoboni M. Experience-dependent modulation of motor corticospinal excitability during action observation. Experimental Brain Research. 2001;140:241–244. doi: 10.1007/s002210100827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattar A, Gribble P. Motor Learning by Observing. Neuron. 2005;46:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miall RC, King D. State estimation in the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2008;7:572–576. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky SH, Schafer JG, Abrams MT, Goldberg MC, Flower AA, Boyce A, Courtney SM, Calhoun VD, Kraut MA, Denckla MB, Pekar JJ. fMRI evidence that the neural basis of response inhibition is task-dependent. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2003;17:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder T. Motor imagery and action observation: cognitive tools for rehabilitation. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2007;114:1265–1278. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0763-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair DG, Purcott KL, Fuchs A, Steinberg F, Kelso JA. Cortical and cerebellar activity of the human brain during imagined and executed unimanual and bimanual action sequences: a functional MRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2003;15:250–260. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols T, Brett M, Andersson J, Wager T, Poline JB. Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. Neuroimage. 2005;25:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page SJ, Levine P, Leonard A. Mental practice in chronic stroke: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Stroke. 2007;38:1293–1297. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260205.67348.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard N, Strick PL. Motor areas of the medial wall: a review of their location and functional activation. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:342–353. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz W. Perception and action planning. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 1997;9:129–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Fadiga L, Matelli M, Bettinardi V, Paulesu E, Perani D, Fazio F. Localization of grasp representations in humans by PET: 1. Observation versus execution. Exp Brain Res. 1996;111:246–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00227301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby P, Decety J. Effect of subjective perspective taking during simulation of action: a PET investigation of agency. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4:546–550. doi: 10.1038/87510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabate M. Brain lateralization of motor imagery: motor planning asymmetry as a cause of movement lateralization. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Jones P, Carpenter T, Baron J. Mapping the involvement of BA 4a and 4p during Motor Imagery. NeuroImage. 2008;41:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Pomeroy VM, Baron JC. Motor imagery: a backdoor to the motor system after stroke? Stroke. 2006;37:1941–1952. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226902.43357.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Bonnelle V, De Boissezon X, Beckmann CF, James SG, Patel MC, Mehta MA. Distinct frontal systems for response inhibition, attentional capture, and error processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6106–6111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000175107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmuelof L, Zohary E. Mirror-image representation of action in the anterior parietal cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11:1267–1269. doi: 10.1038/nn.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirigu A, Cohen L, Duhamel JR, Pillon B, Dubois B, Agid Y, Pierrot-Deseilligny C. Congruent unilateral impairments for real and imagined hand movements. Neuroreport. 1995;6:997–1001. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199505090-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirigu A, Duhamel JR, Cohen L, Pillon B, Dubois B, Agid Y. The mental representation of hand movements after parietal cortex damage. Science. 1996;273:1564–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan KM, Fink GR, Passingham RE, Silbersweig D, Ceballos-Baumann AO, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS. Functional anatomy of the mental representation of upper extremity movements in healthy subjects. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:373–386. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strafella AP, Paus T. Modulation of cortical excitability during action observation: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2289–2292. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200007140-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC. A Population-Average, Landmark- and Surface-based (PALS) atlas of human cerebral cortex. Neuroimage. 2005;28:635–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC, Drury HA, Dickson J, Harwell J, Hanlon D, Anderson CH. An integrated software suite for surface-based analyses of cerebral cortex. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8:443–459. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2001.0080443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt S, Thomaschke R. From visuo-motor interactions to imitation learning: Behavioural and brain imaging studies. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2007;25:497–517. doi: 10.1080/02640410600946779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM, Miall RC, Kawato M. Internal models in the cerebellum. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1998;2:338–347. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]