Abstract

Changes in typical whole-animal dependent variables following drug administration represent an integral of the drug’s pharmacological effect, the individual’s autonomic and behavioral responses to the resulting disturbance, and many other influences. An archetypical example is core temperature (Tc), long used for quantifying initial drug sensitivity and tolerance acquisition over repeated drug administrations. Our previous work suggested that rats differing in initial sensitivity to nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced hypothermia would exhibit different patterns of tolerance development across N2O administrations. Specifically, we hypothesized that rats with an initially insensitive phenotype would subsequently develop regulatory overcompensation that would mediate an allostatic hyperthermic state, whereas rats with an initially sensitive phenotype would subsequently compensate to a homeostatic normothermic state. To preclude confounding due to handling and invasive procedures, a valid test of this prediction required non-invasive thermal measurements via implanted telemetric temperature sensors, combined direct and indirect calorimetry, and automated drug delivery to enable repeatable steady-state dosing. We screened 237 adult rats for initial sensitivity to 70% N2O-induced hypothermia. Thirty highly sensitive rats that exhibited marked hypothermia when screened and 30 highly insensitive rats that initially exhibited minimal hypothermia were randomized to three groups (n=10 each/group) that received: 1) twelve 90-min exposures to 70% N2O using a classical conditioning procedure, 2) twelve 90-min exposures to 70% N2O using a random control procedure for conditioning, or 3) a no-drug control group that received custom-made air. Metabolic heat production (via indirect calorimetry), body heat loss (via direct calorimetry) and Tc (via telemetry) were simultaneously quantified during N2O and control gas administrations. Initially insensitive rats rapidly acquired (3rd administration) a significant allostatic hyperthermic phenotype during N2O administration whereas initially sensitive rats exhibited classical tolerance (normothermia) during N2O inhalation in the 4th and 5th sessions. However, the sensitive rats subsequently acquired the hyperthermic phenotype and became indistinguishable from initially insensitive rats during the 11th and 12th N2O administrations. The major mechanism for hyperthermia was a brisk increase in metabolic heat production. However, we obtained no evidence for classical conditioning of thermal responses. We conclude that the degree of initial sensitivity to N2O-induced hypothermia predicts the temporal pattern of thermal adaptation over repeated N2O administrations, but that initially insensitive and sensitive animals eventually converge to similar (and substantial) magnitudes of within-administration hyperthermia mediated by hyper-compensatory heat production.

Keywords: Allostasis, Homeostasis, Drug tolerance, Addiction, Thermoregulation, Calorimetry, Sign-reversal, Associative tolerance, Homotopic conditioned reflex, Homoreflex, Drug-Onset-Cue

1. Introduction

Previous work from our laboratory demonstrated that rats given repeated exposures to steady state 60% nitrous oxide (N2O1) adapt to the drug's hypothermic effect with a thermoregulatory pattern that differed depending on initial hypothermic sensitivity and age. Rats that exhibited high sensitivity to hypothermia during an initial exposure to 60% N2O (initially sensitive rats) adapted so as to develop tolerance in the classical sense over six subsequent administrations; i.e., core temperature (Tc) remained close to pre drug-exposure levels during N2O inhalation (Ramsay et al., 2005). By contrast, rats that initially exhibited low hypothermic sensitivity (initially insensitive rats) adapted so as to mount a significant hyperthermic sign reversal of Tc during subsequent N2O exposure (Ramsay et al., 2005). We then reported that, in contrast to mature rats, adolescent rats are more sensitive to hypothermia during an initial 60% N2O administration (Kaiyala et al., 2007b). Adolescent rats also adapted rapidly over subsequent exposures so as to evince hyperthermia during drug inhalation (Kaiyala et al., 2007b). This work employed a total calorimetry and temperature model (Kaiyala and Ramsay, 2005) that permits quantification not just of the variable used to operationally define drug sensitivity and tolerance (Tc) but also of the underlying drug effect(s) and regulatory response(s) that account for hypothermic sensitivity and tolerance. The physiological response that mainly accounted for both the tolerant state and the hyperthermic state during drug administration was a prompt and robust increase in the rate of metabolic heat production (HP) upon the initiation of drug exposure, whereas the effect of N2O to increase the rate of body heat loss (HL) remained relatively unchanged with repeated drug exposures (Kaiyala et al., 2007b). Thus, with repeated 60% N2O exposure, the major acquired thermal adaptation that opposes hypothermia is an increase of HP that acts to nullify or overcompensate for the HL-promoting effect of the drug, and this HP response develops rapidly in mature rats that are initially insensitive to N2O hypothermia, but also develops rapidly in young adolescent rats that are initially sensitive to this effect.

The present study sought to determine whether: 1) the acquisition of thermal overcompensation during repeated N2O administration is limited in mature rats to those with an initially insensitive phenotype, or instead will also occur in initially sensitive rats if they are given a sufficient number of drug exposures, and 2) whether physiological effectors that mediate the acquisition of tolerance or hyperthermia could be elicited as conditioned responses.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Subjects

Male Long-Evans rats (n=237) were obtained from Charles River and housed in groups of 2–3 rats per cage with free access to pelleted chow (5053 PicoLab Diet 20, LabDiet, Brentwood, MO) and water. The AAALAC-accredited satellite animal housing room contained within our laboratory had a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle (0700–1900 h) and an ambient temperature of 21± 1°C. The rats weighed 267 ± 66 (SD) g at test. The University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the animal procedures.

2.2 Surgical procedure

Seven to 10 days prior to testing, a battery-operated telemetric temperature sensor was surgically implanted into each rat’s peritoneal cavity. Rats received the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug Meloxicam (Boehringer Ingelheim) in drinking water (0.02 mg/ml H2O) from one day before through two days following surgery. Surgical anesthesia was induced and maintained with isoflurane (3–5% for induction and 1–3% for maintenance).

2.3 System for drug administration, calorimetry and core temperature assessment

This research employed a six station variant of the total calorimetry, temperature and drug administration system described in detail elsewhere (Kaiyala et al., 2007a, b; Kaiyala and Ramsay, 2005) (and online Appendix). Each station simultaneously measures a rat’s Tc via an intraperitoneally implanted telemetric temperature sensor, the dry heat loss (DHL) rate via a direct gradient layer calorimeter (GLC) that also serves as the exposure chamber, the evaporative heat loss (EHL) rate via a thermohygrometer, and the animal’s HP rate via a respirometric indirect calorimeter. These measurements occurred continuously during an initial 2-hour baseline period of control gas administration (custom-blended air) and continued during steady state administration of 70% N2O or continued control gas administration in the subsequent experimental period that lasted 2 hours for the screening N2O exposure and 1.5 hours for the subsequent repeated N2O exposures as described below. Gas delivery was automated and the incurrent O2 concentration was maintained at 21%.

2.4 Conditioned stimuli

Two earbud audio speakers were installed below a plastic waste tray floor at opposite corners of each GLC; when activated these generated clicks as a 10 msec spike at a frequency of 5 Hz. Two white-light LEDs were positioned along opposite corners of the GLC to emit flashing light toward the lid. Light flashes were presented as a 100 msec pulse at a frequency of 3 Hz. A computer controlled the delivery of flashing lights and audible clicks (L&C) that were intended to serve as stimuli to associate with prolonged N2O delivery in a drug conditioning paradigm.

2.5 Energy computations

DHL was computed by multiplying each GLC’s calibration constant (in W/mV) times the mV calorimeter signal output. Due to recurring problems with instrumentation used to measure EHL, these data were excluded from analysis in this study. HP was calculated based on VO2 and an assumed respiratory exchange ratio of 0.85 (N2O interferes with the measurement of CO2 (Kaiyala and Ramsay, 2005)). HP was calculated with the Lusk formula: HP(W) = (0.2662 + 0.08595*RER)*VO2(ml/min) (Kaiyala and Ramsay, 2011).

2.6 Experimental design and procedures

Fig. 1 illustrates the study design, and gives sample sizes and key details (see online Appendix for additional detail). The 25th session was designed to test for conditioned responses to the L&C stimulus. The 1.5-hour experimental period commenced with the 1.4 minute N2O administration with the remainder of the 88.6-minute period accompanied by the L&C stimulus in the absence of N2O inhalation. Our design emphasized within-subjects tests for conditioned responses by comparing each thermal outcome in session 25 with its value in session 24.

Figure 1. Experimental design.

(A) We categorized rats as being initially sensitive or initially insensitive to N2O-induced hypothermia based on Z-scores for magnitudes of hypothermia and within-session recovery of Tc during initial 70% N2O administration. (B) Group Tc values during screening (mean ± 95% confidence interval); black bar on X-axis indicates drug exposure period. (C) Selected rats were randomized to one of three chronic exposure groups such that each group consisted of n=10 initially sensitive and n=10 initially insensitive rats: 1) a control-gas control group that received custom-made air (white bars with and without circles) in lieu of 70% N2O, 2) a conditioning group in which N2O exposure was reliably paired with a lights and clicks (L&C) stimulus (black bars with white circles denotes the persistent L&C stimulus), and 3) a random control group in which N2O exposure was not reliably paired with the L&C stimulus (note the occurrence of the L&C stimulus denoted by circles during control gas exposures). Rats that received N2O experienced interlineated exposures to control gas, with all exposures in these groups involving an initial 1.4-min administration of 70% N2O to avert the possibility that N2O onset might become a conditioned stimulus. Selected rats were given 25 exposure sessions (plus a 26th exposure involving 70% N2O for control gas control rats). The boxes surrounding sessions 1, 6, and 24 indicate that all rats within a given group received the same protocol during those sessions to permit planned comparisons among groups. In sessions 1–24, the conditioning group received 12 exposures to 70% N2O that were always paired with the persistent L&C stimulus that commenced 1.4 min after N2O onset, whereas the other 12 exposures entailed only a brief (1.4-min) N2O onset period followed by 88.6-min of control gas inhalation. The intent was for the rats to learn that N2O continued only if the L&C stimulus occurred following the initial period of N2O administration. In the conditioning group, the sessions involving the brief 1.4-min N2O exposure that were followed by control-gas administration, and the prolonged N2O exposures that were accompanied by the L&C stimulus, were randomly sorted during sessions 2–5 and 7–23 (schematic gives one example of sorting). In sessions 1–24 in the random control group, neither the L&C stimulus nor the initial N2O onset period were reliably paired with the 12 extended 70% N2O administrations such that neither drug onset nor L&C reliably predicted prolonged N2O inhalation. The brief N2O-L&C trials, and the N2O only trials were randomly sorted during sessions 2–5 and 7–23 (schematic gives one example). In sessions 1–24, the control gas control group inhaled only custom-blended air. The L&C stimulus occurred during 12 of these control gas administrations, and the order of L&C trials and blank trials were randomly sorted during sessions 2–5 and 7–23 (one example is shown). In session 25, the L&C stimulus was presented to all groups during control gas administration. Evidence for conditioning would be reliable changes only in the conditioning group of one or more thermal outcomes (Tc, heat production, heat loss) in session 25 compared to these outcomes in session 24.

As a test of the reliability of individual differences to N2O-induced hypothermia, the control gas control group underwent a 26th session in which they were exposed for a second time to 70% N2O for 120 minutes.

2.7 Data reduction and statistical analysis

Data shown with uncertainty bars in figures are expressed as mean ± 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was established at α < 0.05, two-tailed. For each rat, data sampling rates were as follows: Tc: 4/minute: HP and HL data: 6/minute. Data for each outcome were averaged into 5-minute bins for statistical and graphical purposes. HP (Kaiyala and Ramsay, 2005) and HL in the initial 10 minutes following N2O onset exhibit artifactual changes. Accordingly, HP and HL data in the first two 5-minute bins of the experimental period were excluded from graphical and statistical analyses. A derived measure of the ease with which heat flows from the body, dry conductance (Cd), was formed by dividing DHL by the core-to-ambient temperature difference (Gordon, 1993).

Change (Δ) scores were computed for each thermal outcome by subtracting the baseline value from the absolute value. Baseline values were defined as the average of the two 5-minute bins immediately prior to the experimental period. For each variable, we computed two dependent measures, an early Δ score and a mean Δ score. The early Δ score was the average of the 3rd and 4th 5-minute bins of the experimental period. The mean Δ score was the average of the 3rd through the final 5- minute bins of the experimental period. Longitudinal data were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Liang and Zeger, 1986; Ramsay et al., 2005) ((PASW Statistics, v. 18, IBM, Somers, NY). Because baseline values tend to be correlated with Δ scores (Nagoshi et al., 1986), GEE analyses of thermal outcomes were adjusted for within-session baseline values. Baseline-adjusted within-session group comparisons were performed with the general linear model in PASW. In addition, we show in figures the 95% confidence intervals to facilitate visual assessment of the reliability of group differences.

3. Results

3.1 Screening

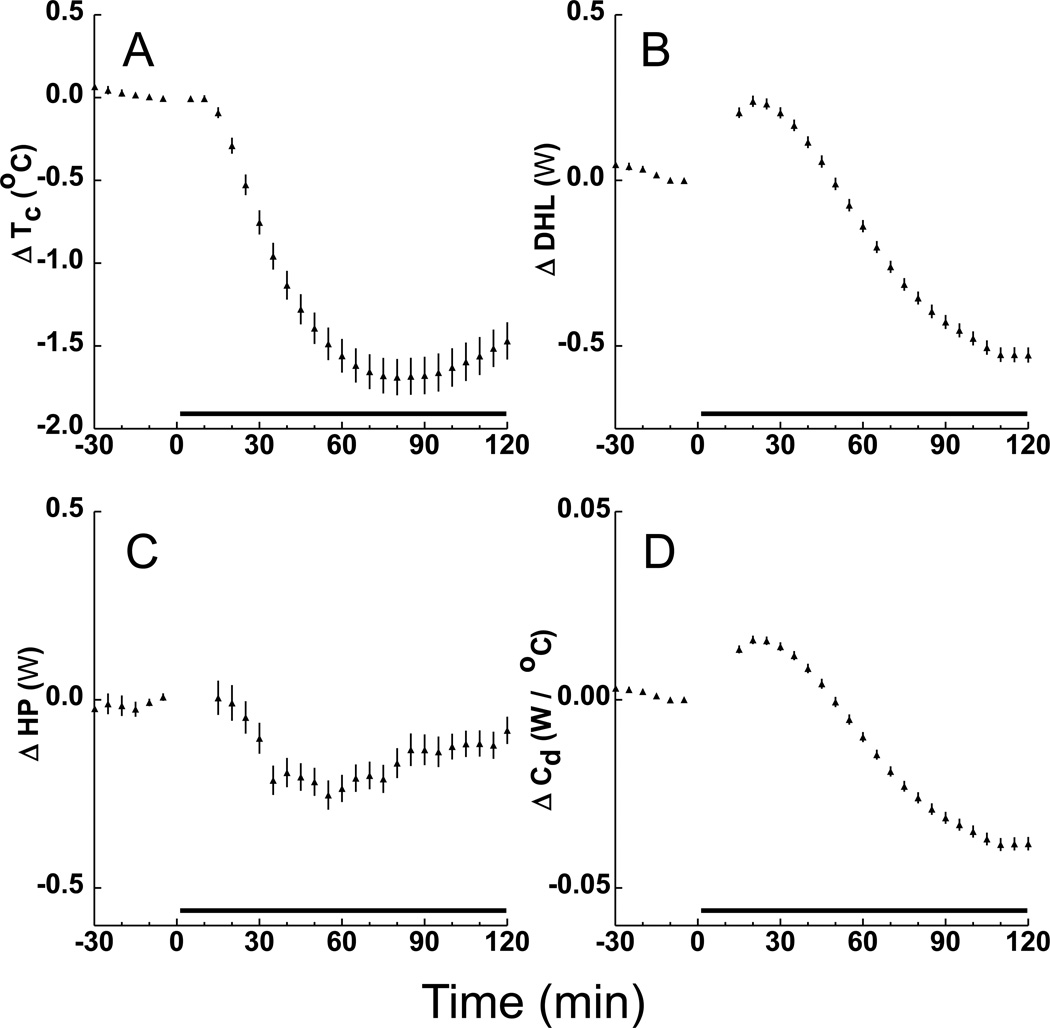

Fig. 2 shows the mean and 95% confidence interval values for Tc, DHL, HP and Cd during the 2-hour screening administration of 70% N2O of 237 rats. These data are consistent with the concept that hypothermia evoked by N2O (panel A) is caused by an acute effect of the drug to increase DHL (Fig. 2B) and perhaps also to suppress HP (Fig. 2C). (The latter possibility must be interpreted cautiously, however, because body tissue temperature itself is a potentially important determinant of HP owing to the Q10 effect whereby metabolic reaction rates have a strong dependence on the temperature at which the reaction takes place). Note that DHL subsequently decreased to levels well below baseline (Fig. 2B), suggesting an adaptation serving to staunch the loss of body temperature. However, this interpretation must be made cautiously because an important driver of DHL, the Tc-to-Tambient gradient, decreased during N2O administration. A traditional method to control for this driving effect is to divide DHL by the Tc-to-Tambient gradient to form the conductance measure Cd; the temporal profile of this outcome (Fig. 2D) suggests that animals do undergo adaptations to staunch DHL during prolonged N2O administration.

Figure 2.

Overall mean ± 95% confidence interval values for thermal outcomes expressed as the change (Δ) from baseline during screening (n=237). Black bars on X-axis shows period of 70% N2O administration. The hypothermic core temperature (Tc) profile in panel A is congruent with the initial increase of dry heat loss (DHL) in B and the decrease of heat production (HP) in C. Panel D shows conductance (Cd) defined as DHL per degree of the core-to-ambient temperature gradient, considered a measure of how readily heat flows from the animal. Data for first two 5-min bins not shown in C–D.

3.2 Adaptation to repeated N2O administration

The patterns with which Tc and the effector outputs that determine this regulated variable adapted to drug exposure across the 13 exposures are shown in Fig. 3. In the screening exposure, mean Tc changes in the insensitive and sensitive groups were −0.52±0.06 vs. −1.71±0.08 °C, respectively (p<0.0001). Baseline-adjusted ΔTc averages within exposures (Fig. 3A) exhibited highly significant effects of group, exposure and the group by exposure interaction (p < 0.0001 for all three terms). Comparing adjusted average ΔTc between the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive rats indicated a highly significant difference between groups (p<0.0001) and formally indicated that the sensitive group underwent a significantly greater rate of increase in average ΔTc across exposures compared to the insensitive group (0.122±0.0095 vs. 0.042±0.012 oC/exposure; p<0.0001). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 drug exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted average ΔTc of the insensitive rats was significantly higher compared to sensitive rats in all except the final two exposures (0.00001≤p≤0.037).

Figure 3.

Thermal adaptations in core temperature (Tc), dry heat loss (DHL) and heat production (HP) during repeated 70% N2O administrations in rats selected to represent extremes of initial sensitivity to hypothermia in the screening (S) administration. Uncertainty bars are 95% confidence intervals. Control rats received control gas (custom-blended air) during exposures. Panels on the left show changes in thermal values averaged across 90-minute (Tc) and 77.5 minutes (DHL and HP) periods of drug administration (for DHL and HP, the first 12.5 minutes of data were excluded owing to potential for artifactual values therein). Panels on the right show early changes averaged over the second and third 5-min bins following drug onset. The 12 drug exposures following screening were each separated by 1–2 day intervals in which no N2O administrations occurred. Panels A and B show that the initial hypothermia during N2O yielded to a state of tolerance (i.e., no change of Tc from baseline) but then subsequently inverted to significant hyperthermia during drug administration. The smooth lines represent elementary first order exponential growth curve fits to the mean data of the form Y = b0 + b1(1-exp(b3 X)). Key points: Initially insensitive rats exhibited Tc tolerance on the 1st post-screening administration and developed a hyperthermic intra-administration phenotype more rapidly than sensitive rats based on when 95% confidence intervals exclude zero. We note that the fitted exponential rate constants (b3) for insensitive vs. sensitive rats were 0.44±0.13 vs. 0.34±0.04, respectively. The hyperthermic sign reversal is highly congruent with the robust intersessional increases of HP during N2O administration (E and F). The increase of average DHL across sessions reflects the increase of HP, a major driver of HL. Early differences in HP and DHL may be especially important in determining Tc phenotypes during N2O administration. *p<0.05 for insensitive vs. sensitive by independent samples Student’s t-test. Baseline-adjusted p-values are reported in Results.

Session 6 (Fig. 1C) (corresponding to drug exposure 3 in Fig. 3A,B) involved group comparisons that were planned such that the two N2O-treated groups had experienced the same number of previous drug exposures (a 2-h screening and two 90-minute sessions). It is noteworthy that in session 6, baseline adjusted Tc outcomes still differed significantly between the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive groups (exposure 3 in Fig. 3A,B; mean ΔTc, 0.33±0.071 vs. −0.26±0.071 °C, respectively; p<0.0001; early ΔTc: 0.45±0.045 vs. 0.13±0.045 °C, respectively; p <0.0001). By contrast, the conditioning and random control groups did not differ in session 6 (p ≥ 0.94), indicating a state of thermal equivalence between these groups at this time-point. Baseline-adjusted early ΔTc within exposures (Fig. 3B) exhibited highly significant effects of group, exposure and the group by exposure interaction (p < 0.0001 for all three). Comparing adjusted early ΔTc between the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive rats indicated a highly significant difference between groups (p<0.0001) and statistically confirmed that the sensitive group underwent a significantly greater rate of increase of early ΔTc across exposures compared to the insensitive group (0.04±0.007 vs. 0.002±0.006 °C/exposure; p<0.0001). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted early ΔTc of the insensitive rats was significantly higher compared to sensitive rats in exposures 1–4, 6, and 8 (0.00001≤p≤0.001).

We did not anticipate that within session overall and early Tc outcomes for the initially sensitive and insensitive rats would converge to similar hyperthermic values in the latter administrations (Fig. 3 A,B). In the final exposure, mean Tc changes for initially insensitive vs. initially sensitive rats were 0.48±0.14 vs. 0.62±0.10 °C, respectively. Thus, the initial sensitivity to N2O hypothermia did not evidently reflect differential characteristics of the phenotypes that persist indefinitely across repeated drug exposures. It is obvious by inspection that control rats exposed only to custom-made air exhibited almost no mean or early changes of Tc across administrations.

In the screening exposure, baseline-adjusted average ΔDHL (Fig. 3C) was similar between initially insensitive and sensitive rats (−0.10±0.02 vs. −0.06±0.02 W; p=0.18). Over the subsequent 12 exposures, baseline-adjusted average ΔDHL exhibited significant effects of group, exposure and the group by exposure interaction (p < 0.0001 for all three). However, restricting the comparison of adjusted average ΔDHL to the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive rats indicated no difference between groups (p=0.88). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted (but not unadjusted) average ΔDHL of the sensitive rats was significantly higher compared to insensitive rats only within exposure 12 (p=0.028). Notably, the average within-session increase of DHL achieved an asymptotic plateau over the latter 5–6 exposures (Fig. 3C). This observation is consistent with the concept that increased heat loss is a primary pharmacological effect of N2O.

Inspection of Fig. 3C indicates that control rats generally exhibited small and non-significant decreases of average DHL across exposures, and the 95% confidence intervals indicate that they differed significantly from the N2O-treated rats during exposures 1–12.

In the screening exposure, baseline-adjusted early ΔDHL (Fig. 3D) differed between initially insensitive and sensitive rats (0.16±0.03 vs. 0.27±0.02 W; p = 0.003). Over the subsequent 12 exposures, the early baseline-adjusted ΔDHL within exposures (Fig. 3D) exhibited significant effects of group (p<0.0001), exposure (p=0.002) and a trend for a group by exposure interaction (p =0.056). Regression analyses indicated that the sensitive group underwent a significant rate of decrease of early ΔDHL across exposures (−0.009±0.0024 W/exposure; p=0.0002) whereas the insensitive group did not (−0.001±0.009 W/exposure; p=0.69). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted early ΔDHL of the sensitive rats was significantly higher compared to insensitive rats through exposure 4, in which the difference was 0.08±0.035 W (p = 0.02). Inspection of Fig. 3D indicates that control rats exhibited minimal changes of early DHL across exposures, and the 95% confidence intervals indicate that they differed significantly from N2O-treated rats during exposures 1–12. A greater propensity for increased DHL during N2O would predispose to greater hypothermia. Thus, an important distinction between rats classified as initially sensitive vs. insensitive (based on Tc) is that the former also exhibit a greater sensitivity to N2O’s effect to increase DHL in the early portion of N2O administration.

In contrast to the observation that the average within-session increase of DHL achieved an asymptotic plateau over the latter 5–6 exposures (Fig. 3C), HP (Fig. 3E–F) not only increased more robustly across drug exposures but also approached an asymptotic level that exceeded that of DHL, consistent with having a role as a dynamic adaptive regulatory response that dominates the overall thermal adaptation to repeated high-concentration N2O administrations.

In the screening exposure, baseline-adjusted average ΔHP (Fig. 3E) differed significantly between initially insensitive and sensitive rats (−0.18±0.04 vs. −0.23±0.04 W, respectively; p=0.004). Over the subsequent 12 exposures, baseline-adjusted average ΔHP within exposures exhibited significant effects of group (p=0.009), N2O exposure (p<0.0001) and the group by N2O exposure interaction (p < 0.0001). Comparing adjusted average ΔHP between the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive rats also indicated an overall difference between groups (p=0.002) and revealed that the sensitive group underwent a significantly greater rate of increase of average ΔHP across exposures compared to the insensitive group (0.066±0.0053 vs. 0.046±0.0063 W/exposure; p=0.013). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted average ΔHP of the sensitive rats was significantly higher compared to insensitive rats only within exposure 12 (p=0.017).

Baseline-adjusted early ΔHP within exposures (Fig. 3F) exhibited significant effects of group (p=0.012), exposure (p<0.0001) and the group by exposure interaction (p<0.0001). Comparing adjusted early ΔHP between the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive rats disclosed an overall difference between groups (p=0.009) with initially insensitive rats having a greater HP response. However, the two groups underwent similar average rates of increase in early ΔHP across exposures (sensitive = 0.058±0.0065 vs. insensitive=0.045±0.010 W/exposure; p=0.28). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted early ΔHP of the insensitive rats was significantly higher compared to sensitive rats within exposures 3,5,6, and 8 (Fig. 3F).

Consistent with this assessment, Fig. 3E shows that average within-session HP increased markedly from baseline across exposures in both sensitivity groups. Additionally, the longitudinal pattern of this adaptation was similar between groups, although insensitive rats maintained significantly higher HP than sensitive rats in the screening administration (Fig. 3E), which would be expected to favor resistance to N2O hypothermia. Beyond that finding, and the observation of a significant but inverted group difference in the final administration, regression analysis encompassing all 13 exposures revealed no reliable overall difference between the N2O-treated sensitivity groups (p = 0.44 after adjustment for baseline HP and exposure number).

Notably, the robust intrasessional growth of HP was manifest in the early period of drug exposure (Fig. 3F), consistent with development of a brisk regulatory response that initially counters hypothermia and subsequently favors hyperthermia. Regression analysis encompassing all 13 exposures revealed a reliable overall difference between the N2O-treated sensitivity groups (p = 0.043 after adjustment for baseline HP and exposure number). Thus, compared to initially hypothermia-sensitive rats, the thermal adaptive profile of initially insensitive rats exhibited a more robust adaptation of an early session HP counter response.

Fig. 4 shows within-session temporal profiles of thermal outcomes stratified by exposure number. Notable features include the observations that mean hyperthermic changes of Tc in the latter exposures achieved and maintained relative steady state levels (Fig. 4A) and that these profiles were underlain by a “primed infusion” of heat as revealed by the initial topography of the HP response (Fig. 4C,F). The “primed infusion” topography is particularly striking in the initially insensitive group (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Temporal profiles of core temperature (Tc), dry heat loss (DHL) and heat production (HP) in initially sensitive and insensitive rats as defined by Tc excursions during screening. Numbers by lines indicate exposures 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12. Black bars show period of drug administration. Data are not shown for DHL and HP during the initial period of N2O administration owing to potential for artifactual changes. Key points: rats appear to develop hypothermic tolerance and the subsequent hyperthermic sign reversal via a HP response that is especially brisk in the first 30 minutes of drug administration.

Fig. 5 shows profiles of whole body dry conductance (Cd), an index of the ease with which heat flows from the body. The patterns of ΔCd are similar to those of ΔDHL. In the screening exposure, baseline-adjusted average ΔCd (Fig. 5A) was similar between initially insensitive and sensitive rats (−0.007±0.001 vs. −0.006±0.002 W/°C, respectively; p=0.51). Over the subsequent 12 exposures, baseline-adjusted average ΔCd within exposures exhibited significant effects of group (p=0.0004), and the group by exposure interaction (p < 0.0001), but not exposure (p=0.95). Comparing adjusted average ΔCd between the N2O-treated initially insensitive and sensitive rats did not indicate an overall difference between groups (p=0.61) and indicated that the insensitive and sensitive groups underwent similar rates of increase of average ΔCd across exposures (0.00006±0.0001 vs. 0.0005±0.0002 W/°C/exposure; p=0.07). When separate analyses were performed within each of the 12 exposure sessions to compare the N2O-treated groups, the baseline-adjusted average ΔCd of the sensitive rats was significantly higher compared to insensitive rats within exposure 9 (p=0.025) and approached significance in exposure 12 (p=0.054).

Figure 5.

Changes of dry conductance (Cd) with repeated N2O administration. Uncertainty bars are 95% confidence intervals. Key points: Early changes of Cd, a measure of the ease with which heat flows from the body, distinguish the sensitivity groups in earlier but not later exposures. * p<0.05 for initially insensitive vs. sensitive rats.

3.3 Drug Conditioning

To test for evidence of conditioning, we compared thermal outcomes on the test day (session 25) to those on the previous control day (session 24) using linear mixed model analyses that controlled for baseline thermal values (body mass was determined to be an unimportant covariate and thus was excluded from analyses). None of the thermal responses within the conditioning group (the group of primary interest) differed by initial sensitivity group or by session, so the initial sensitivity groups were combined in subsequent analyses. We found no reliable evidence for conditioned thermal responses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tests for conditioned responses. Tc: core temperature; HP: heat production, DHL: dry heat loss. Units: degrees centigrade for Tc; watts for HP and DHL. Test minus control difference for change scores are baseline-adjusted values on the test day (session 25) minus baseline-adjusted values on the control day (session 24); see Material and methods and Fig. 1C.

| Group | Dependent variable |

Test minus control Δ |

SE | P | Baseline on test day (SE)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditioning | Early Δ Tc | −0.037 | 0.052 | 0.491 | 37.156 (0.077) |

| Mean Δ Tc | −0.101 | 0.052 | 0.075 | ||

| Baseline Tc | 0.053 | 0.075 | 0.487 | ||

| Early Δ HP | 0.092 | 0.078 | 0.254 | 4.859 (0.165) | |

| Mean Δ HP | 0.016 | 0.025 | 0.541 | ||

| Baseline HP | 0.073 | 0.132 | 0.588 | ||

| Early Δ DHL | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.962 | 4.749 (0.122) | |

| Mean Δ DHL | −0.022 | 0.016 | 0.202 | ||

| Baseline DHL | 0.088 | 0.083 | 0.300 | ||

| Random control | Early Δ Tc | −0.076 | 0.068 | 0.278 | 37.221 (0.109) |

| Mean Δ Tc | −0.010 | 0.059 | 0.873 | ||

| Baseline Tc | −0.079 | 0.051 | 0.142 | ||

| Early Δ HP | 0.050 | 0.118 | 0.673 | 4.561 (0.114) | |

| Mean Δ HP | 0.104 | 0.065 | 0.119 | ||

| Baseline HP | −0.309 | 0.138 | 0.039 | ||

| Early Δ DHL | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.412 | 4.614 (0.278) | |

| Mean Δ DHL | 0.029 | 0.032 | 0.381 | ||

| Baseline DHL | −0.080 | 0.062 | 0.213 | ||

| Control gas control | Early Δ Tc | 0.010 | 0.056 | 0.861 | 37.190 (0.110) |

| Mean Δ Tc | −0.013 | 0.057 | 0.819 | ||

| Baseline Tc | 0.036 | 0.056 | 0.534 | ||

| Early Δ HP | 0.435 | 0.081 | <0.0001 | 4.740 (0.068) | |

| Mean Δ HP | 0.016 | 0.044 | 0.723 | ||

| Baseline HP | −0.063 | 0.249 | 0.271 | ||

| Early Δ DHL | 0.086 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 4.672 (0.450) | |

| Mean Δ DHL | −0.009 | 0.025 | 0.705 | ||

| Baseline DHL | −0.048 | 0.044 | 0.291 | ||

Pairwise comparisons of baseline values disclosed no significant differences between groups (Tc, p> 0.657; DHL, p>0.33; HP, p>0.084).

It is noteworthy that the control gas control group exhibited significant increases in early ΔHP and early ΔDHL (p≤0.004) (but no changes of Tc) on the test vs. control days (Table 1). These non-conditioned effects likely reflect the fact that this group received the initial 1.4 minute N2O administration for the first time when evaluated on the test day, consistent with our attempt to select a brief period of N2O inhalation that causes a physiological reaction. In fact, we designed our study to include a between-groups test to verify that this brief exposure has an effect: in sessions 1 and 24, the conditioning and random control groups received the initial 1.4 minute period of N2O while the control gas control rats did not (Fig. 1C). In these sessions, the early ΔHP was significantly greater in the rats that received the brief N2O exposure than in the control gas control group (respective group means for session 1=0.158±0.038 vs. 0.019±0.053 W; p = 0.026; session 24=0.236±0.045 vs. 0.000+0.060 W; p=0.003). However, no significant differences in the early ΔDHL were observed between groups in sessions 1 or 24. Collectively, these data indicate that a brief initial period of N2O inhalation can have physiological effects, consistent with the concept that this could serve as an interoceptive cue.

With one exception, baseline thermal values did not differ between the test and control days (Table 1). The exception was baseline HP in the random control group. This could well be a chance finding.

3.4 Reliability analysis

In the reliability test, Tc data were acquired for n=16 of the 20 control gas control rats (4 rats were inadvertently not tested). Initially sensitive rats remained sensitive compared to initially insensitive rats in average hypothermic magnitude during 70% N2O exposure (−0.78±0.17 vs. 0.03±0.10 °C, respectively; p = 0.002). It is notable that the groups remained distinct despite a ~40 day interval between the screening and reliability tests and an increase in body mass of ~86% (250±7 vs. 464± 6 g). The initially sensitive and insensitive groups did not differ at retest in baseline Tc (37.10±0.07 vs. 37.02±0.23 g, respectively; p=0.72) or body mass (465±8 vs. 455±11 g, respectively; p=0.70). The correlation (Pearson r) between ΔTc in the screening and retest evaluations was r=0.73; p = 0.002.

In the reliability test, initially sensitive rats also remained distinct from initially insensitive rats in average ΔHP magnitude during 70% N2O exposure (−0.09±0.074 vs. 0.31±0.085 W, respectively; p = 0.004). The same pattern of results occurred for the early ΔHP outcome (0.04±0.18 vs. 0.61±0.18 W; p=0.016, for sensitive vs. insensitive rats, respectively). Thus, just as observed in the original screening exposure, the initially insensitive group differed from the initially sensitive group by generating a significantly higher HP response during N2O inhalation, a result that would be expected to oppose the loss of body heat content in the face of elevated HL.

The initially sensitive and insensitive groups did not differ significantly at retest in baseline HL (2.11±0.07 vs. 2.14±0.11 W, respectively; p=0.76). As in the original screening run, initially sensitive rats did not differ from initially insensitive rats in average ΔDHL magnitude during 70% N2O exposure (0.11±0.04 vs. 0.13±0.05 W, respectively; p = 0.72). The same pattern of results occurred for the early ΔDHL (0.23±0.04 vs. 0.17±0.05 W; p=0.34, for sensitive vs. insensitive rats, respectively).

4. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that rats selected to represent the extremes of sensitivity to the hypothermic effect of 70% N2O in a screening exposure adapted across subsequent repeated exposures so as to generate an allostatic hyperthermic steady state Tc during exposure to this high N2O concentration (Fig. 4). Rats classified as initially insensitive based on minimal Tc change in the initial drug exposure exhibited the development of reliable tolerance to hypothermia sooner than initially sensitive rats (exposure 1 vs. exposure 4; Fig 3A), but subsequently the two groups converged to similar magnitudes of hyperthermia during drug exposure. The present work demonstrating the acquisition of a persistent regulatory overcompensation (hyperthermia) during 70% N2O administration in mature rats extends previous work from our laboratory in which 5 repeated 60% N2O administrations engendered a significant hyperthermic overcorrection in adolescent rats that initially exhibited marked sensitivity to N2O hypothermia (~ −2°C; (Kaiyala et al., 2007b)) whereas adult rats simply became tolerant in the classical sense (i.e., Tc remained at baseline during 60% N2O). In that study (Kaiyala et al., 2007b) a subset of adolescent rats given 11 administrations of 60% N2O acquired a marked within-administration hyperthermia averaging ~1°C in the final administration. We did not determine whether initially sensitive adult rats would eventually acquire a within-session hyperthermic phenotype because they were not studied beyond 5 administrations (Kaiyala et al., 2007b). The present work demonstrates that rats, whether initially sensitive or insensitive to N2O hypothermia, will acquire a within-administration hyperthermic phenotype with initially sensitive rats simply requiring more administrations to do so. These findings constitute unusually direct evidence with intriguing implications for understanding the pathophysiology of drug addiction.

An influential contemporary model in drug addiction holds that chronic drug use engenders persistent dysregulated allostatic changes in levels of regulated physiological variables (e.g., hedonia, and pain) (Koob and Le Moal, 2004, 2008). These states are conceptualized as representing regulated variables that are complexly determined via the integration of competing CNS effector outputs (Koob and Le Moal, 2004) [in analogy with Tc being determined by competing systems that determine rates of heat loss and heat gain (Kaiyala et al., 2007b)]. The phrase “allostatic changes” means that chronic drug use engenders a host of system-level and cellular adaptations that collectively act to drive the regulated variable (e.g., hedonic or pain states) away from their usual balance points in directions that are opposite to the primary pharmacological effects of the drug. These changes embody a durable temporal persistence that is revealed during the drugged-state (as in this study) or could be present or elicited during periods of drug abstinence as a psychophysical state that is opposite in sign to the effects (e.g., withdrawal) classically attributed to the drugs being used or abused, e.g., increased anxiety if the drug in question promotes reduced anxiety. Traditional views have held that tolerance returns the individual to the typical homeostatic balance point of the regulated variable during the drugged state, while an allostatic model can account for an overcompensation of the regulated variable during the drugged state. From an allostatic perspective, administration of the drug in question alleviates the negative state shift both during the drugged state (an allostatic overcorrection) as well during drug withdrawal. Thus, drug taking behavior can be motivated by its ability to counter these allostatic overcompensations during the drugged state or to alleviate withdrawal rather than to produce its initial effects. As mentioned above, the allostatic model relies on an enduring concept in addiction research – opponent responses – to explain allostatic shifts. Opponent responses include CNS-mediated effector responses that counter the primary pharmacological effects of the drug and are often conceptualized in terms of negative feedback-elicited responses evoked by perturbations of regulated systems and/or acquired feed-forward responses that develop via associative learning (Ramsay and Woods, 1997; Siegel, 1978, 1999).

A wealth of evidence indicates that learned opponent responses can serve as conditioned compensatory responses (CCRs). CCRs can contribute both to drug tolerance that is manifest during drug administration and to withdrawal responses that occur when cues that have been associated with the drug (conditioned stimuli) occur in the absence of drug administration (reviewed in (Dworkin, 1993; Siegel, 1999; Siegel et al., 2000)). Our study was designed to probe for evidence of CCRs as a basis of acquired hypothermia-opposing adaptations to N2O administration. We did this by reliably pairing a persistent lights and clicks stimulus with prolonged N2O inhalation and did so such that the brief 1.4 min initial period of N2O inhalation was not a reliable predictor of continued N2O inhalation in the conditioning group. This feature was included owing to the potential for the initial period of drug administration to become an early-drug onset cue type of conditioned stimulus (reviewed in (Sokolowska et al., 2002)). Despite this design feature and other strengths of our design, including a relatively large number of drug administrations, three potentially condition-able thermal outcomes, and the inclusion of two control groups, we did not obtain evidence for classical conditioning as a basis of thermal adaptations that counter N2O’s effect to promote hypothermia. It may be that our design did not provide an appropriate test for conditioning with N2O (e.g., cue competition from the training context). Alternatively, N2O inhalation may oppose the learned acquisition of CCRs because this drug antagonizes neuronal signaling mediated via the NMDA receptor (Jevtovic-Todorovic et al., 1998)), a phenomenon of vital importance to learning and memory (Li and Tsien, 2009). Consistent with this possibility, N2O exposure was reported to counter drug adaptations with a demonstrated dependence on intact NMDA signaling, specifically the development of acute tolerance to morphine analgesia and the development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (Bessiere et al., 2007; Richebe et al., 2005). Accordingly, our data imply that the adaptive mechanisms that underlie the development of a notably robust hyperthermic overshoot during N2O administration do not depend on intact NMDA signaling. This hypothesis suggests that the adaptations that oppose hypothermia during N2O administration depend on non-NMDA dependent pharmacodynamic mechanisms that are engaged in the drug’s presence. The demonstration that a marked acquired increase of HP that overcompensates for N2O’s effect to promote HL occurs despite the reported abrogation of a signal transduction pathway of major importance to neuronal plasticity likely reflects the primacy of thermoregulation to survival. The latter is underlain by an evolutionarily complex and extensively distributed control system imbued with control elements at every level of the neuraxis (Satinoff, 1978). Similarly, a variety of control systems that are engaged and corrupted by a variety of addictive behaviors (pain processing, reward food intake) also involve complex, distributed architectures.

A practical problem with the allostasis model is that the psychophysical state variables of particular motivational significance to drug taking behavior (e.g., hedonic state) and their underlying hedonia- and anhedonia-promoting effector responses do not lend themselves to accurate and detailed continuous measurements that enable relatively direct tests of the model. By contrast, mammalian thermoregulation involves a biobehavioral control system that provides exceptional quantitative access not just to the controlled variable, core temperature (Tc), but also to its underlying effectors at the level of HP and HL. It is likely that the control system for Tc shares properties in common with other biological regulatory systems (Bligh, 1998, 2006; Gordon, 2005) including those involving other drug-influenced variables such as hedonia and pain. Accordingly, insights derived from thermoregulatory models may generalize to a broad range of variables and regulatory systems with relevance to drug addiction.

Our data indicate that this sign reversal of the homeostatically regulated output (Tc) during drug exposure was effected primarily by a “primed infusion” of HP, i.e., an initial prompt overshoot of HP followed by abatement to a lower (yet still elevated relative to baseline) quasi-steady-state during drug administration (Fig. 4E,F). It is worth noting both that the primed infusion technique is well recognized as a means to rapidly achieve a steady state level of infusate in pharmacokinetic studies, e.g., (Kaiyala et al., 2000) and that the briskness of a physiological effector response is a key determinant of the subsequently maintained level of the regulated physiological output (Dworkin, 1993).

Interestingly, the effect of N2O to promote increased early heat loss remained relatively unchanged in the initially insensitive group (Fig. 3D), whereas the early increase of DHL in the initially sensitive group waned across drug exposures so as to become similar to that of the initially insensitive group (Fig. 3D). In both groups, the temporal profiles of DHL during drug exposure exhibited parabola-like trajectories that systematically became shallower in concert with a rightward shift in the apogee of DHL over repeated drug administrations (Fig. 4C,D). These findings suggest that the acquisition of within-session thermal allostasis during N2O exposure also derives to some extent from adaptations serving to staunch heat flow to the environment. To consider this possibility, however, it must be appreciated that heat loss during N2O administrations reflect the interplay of multiple factors, chiefly the thermal conductance of body shell tissues; the effective body surface area as determined by posture; and the temperature gradient between the body core and the environment (relative to which the rate of metabolic HP is an important determinant). Of particular note is that the sharp within-session declines of DHL in the initial exposures mirror the decreases of Tc (compare Fig. 4A,B with C,D). A traditional remedy to “correct” heat loss for changes in Tc is to divide heat loss by the Tc-to-Tambient gradient, yielding a measure termed whole body conductance that gives the rate of HL per degree of temperature gradient (Gordon, 1993). Analysis of dry thermal conductance (Cd; Fig. 5) strengthens the proposition that some adaptation occurs at the level of the ease with which heat flows out of the animal during N2O exposure. It is unknown whether this class of adaptation to repeated N2O administration reflects behavioral (e.g., postural) adjustments that favor heat retention or autonomic changes that promote peripheral vasoconstriction [particularly of cutaneous tail vasculature, a major determinant of heat loss in rats (Gordon, 1993)]. Studies involving behavioral monitoring, measurement of tail blood flow and thermal imaging to quantify heat loss by body surfaces would shed important light on this issue.

A direction of particular interest involves the correspondence – or dissonance – between autonomic and behavioral influences over controlled outputs such as Tc (and ultimately more elusive constructs such as hedonia and pain) during drug administration and other non-naturalistic settings (Woods & Ramsay, 2007). Biobehavioral control systems (such as the aggregate system for thermoregulation) are not structured in accordance with classical control theories’ multiple input-to-one-integrator design. Rather, as originally articulated by Satinoff in 1978 for thermoregulation (Satinoff, 1978), control relies on multiple and relatively independent control loops (Kanosue et al., 2010; McAllen et al., 2010; Werner, 2010). Satinoff proposed that there is an integrator for each thermoregulatory response; that integrators exist at multiple levels of the nervous system; and, that this arrangement fine-tunes and thus optimizes control over body temperature (Satinoff, 1978). However, such an arrangement, while robust to naturalistic disturbances, also involves hidden complexity that confers “control system fragilities,” a concept as advanced by Doyle and coworkers and termed robust yet fragile (RYF) (Csete and Doyle, 2002). RYF is proposed to underlie a host of metabolic and autoimmune diseases (Kitano et al., 2004) and can be extended to include drug dependence. The potential interaction of multiple, independent evolved thermoregulatory control loops and system complexity and fragility in the context of drug administration can be explored using a combination of autonomic and behavioral studies because these modes of control can be readily distinguished. A recent study from our laboratory involving a thermally-graded alleyway that allows rats to select their preferred ambient temperature during N2O inhalation provides a start (Ramsay et al., 2011). Initial exposure to 60% N2O evokes a behavioral response (selection of cooler ambient temperatures) that assists in the development of hypothermia (Ramsay et al., 2011). Interestingly, during the development of acute (intrasessional) tolerance to the hypothermic Tc, it appeared that the behavioral effector and autonomic effectors were not working in a coordinated fashion as would be predicted by a homeostatic model but rather were working in opposition. Current studies are examining whether N2O-adapted rats that have developed an allostatic hyperthermic state during N2O administration will be motivated to behaviorally assist or resist this state.

In summary, chronic administration of 70% N2O engenders a sign reversal in the Tc change during drug administration that occurs primarily via an acquired metabolic rate response, and arises after only several administrations in rats that are insensitive to N2O hypothermia upon initial administration.

Highlights.

Intraperitoneal temperature telemetry demonstrated that, on average, an initial screening administration of 70% nitrous oxide (N2O) to a large group of rats (n=237) caused hypothermia. However, a subset was highly sensitive whereas another subset was relatively insensitive to this hypothermic effect.

Our total calorimetry and temperature model revealed that the initial screening administration promoted increased body heat loss in both subsets of rats. However, in comparison to the hypothermia-sensitive animals, the insensitive rats exhibited a lesser increase of body heat loss early in the administration, and also countered the heat loss effect with greater metabolic heat production. Thus, the “insensitive” rats exhibited “innate” tolerance via an active compensatory response component.

We enrolled 30 animals from both phenotypes into a study involving 12 subsequent exposures to either 70% N2O or control gas, and we also included an associative (Pavlovian) conditioning procedure to determine whether thermal responses could be evoked by cues reliably associated with drug administration.

Both groups of rats adapted across serial administrations of 70% N2O by increasing (or further increasing) intra-administration metabolic heat production, and this adaptation further offset a durable effect of the drug to increase body heat loss.

In the fourth drug administration to the initially sensitive animals, the increase in intra-administration heat production had a magnitude that resulted in classical tolerance to N2O hypothermia, i.e., the rats maintained normothermia as defined by core temperature during N2O inhalation.

With additional N2O administrations to the initially sensitive group, however, the acquired heat production response strengthened even further such that it caused a state of persistent hyperthermia during drug administration. This constitutes a rigorous experimental model of thermoregulatory allostasis in which the regulated variable (core temperature) is maintained at a non-homeostatic, dysregulated value owing to the excessive recruitment of an effector response (heat production).

Thermoregulatory allostasis in the initially insensitive group was evident after just two subsequent drug administrations.

We obtained no evidence for the involvement of an associative mechanism for tolerance / allostasis development, and suggest that this might reflect the known effect of nitrous oxide to antagonize NMDA-mediated signaling, an important element of learning and memory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIDA grants DA016047 and DA023484). We gratefully acknowledge Christopher W. Prall and the late Shehzad Butt for their technical contributions to this study, and thank Dr. Terry Davidson for his insightful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: N2O, nitrous oxide; Tc, core temperature; HP, heat production; HL, heat loss; DHL, dry heat loss; EHL, evaporative heat loss; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate

Contributor Information

Karl J. Kaiyala, Email: kkaiyala@uw.edu.

Ben Chan, Email: benchan159@yahoo.com.

Douglas S. Ramsay, Email: Ramsay@uw.edu.

References

- Bessiere B, Richebe P, Laboureyras E, Laulin JP, Contarino A, Simonnet G. Nitrous oxide (N2O) prevents latent pain sensitization and long-term anxiety-like behavior in pain and opioid-experienced rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh J. Mammalian homeothermy: an integrative thesis. J. Therm. Biol. 1998;23:143–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh J. A theoretical consideration of the means whereby the mammalian core temperature is defended at a null zone. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1332–1337. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01068.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csete ME, Doyle JC. Reverse engineering of biological complexity. Science. 2002;295:1664–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1069981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin BR. Learning and physiological regulation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CJ. Temperature regulation in laboratory rodents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CJ. Temperature and toxicology: an integrative, comparative and environmental approach. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic S, Mennerick S, Powell S, Dikranian K, Beenshoff N, Zorumski CF, Olney JW. Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is an NMDA antagonist, neuroprotect and neurotoxin. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:460–463. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyala KJ, Butt S, Ramsay DS. Direct evidence for systems-level modulation of initial drug (in)sensitivity in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007a;191:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0657-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyala KJ, Butt S, Ramsay DS. Systems-level adaptations explain chronic tolerance development to nitrous oxide hypothermia in young and mature rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007b;191:233–242. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0655-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyala KJ, Prigeon RL, Kahn SE, Woods SC, Schwartz MW. Obesity induced by a high-fat diet is associated with reduced brain insulin transport in dogs. Diabetes. 2000;49:1525–1533. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyala KJ, Ramsay DS. Assessment of heat production, heat loss, and core temperature during nitrous oxide exposure: a new paradigm for studying drug effects and opponent responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R692–R701. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00412.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyala KJ, Ramsay DS. Direct animal calorimetry, the underused gold standard for quantifying the fire of life. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. 2011;158:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanosue K, Crawshaw LI, Nagashima K, Yoda T. Concepts to utilize in describing thermoregulation and neurophysiological evidence for how the system works. European journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:5–11. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H, Oda K, Kimura T, Matsuoka Y, Csete M, Doyle J, Muramatsu M. Metabolic syndrome and robustness tradeoffs. Diabetes. 2004;53 Suppl 3:S6–S15. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction and allostasis. In: Schulkin J, editor. Allostasis, homeostasis and the costs of physiological adaptation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. pp. 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annual review of psychology. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Tsien JZ. Memory and the NMDA receptors. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:302–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr0902052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- McAllen RM, Tanaka M, Ootsuka Y, McKinley MJ. Multiple thermoregulatory effectors with independent central controls. European journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT, Wilson JR, Plomin R. Use of regression residuals to quantify individual differences in acute sensitivity and tolerance to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10:343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay DS, Kaiyala KJ, Leroux BG, Woods SC. Individual differences in initial sensitivity and acute tolerance predict patterns of chronic drug tolerance to nitrous-oxide-induced hypothermia in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:48–59. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2219-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay DS, Seaman J, Kaiyala KJ. Nitrous oxide causes a regulated hypothermia: rats select a cooler ambient temperature while becoming hypothermic. Physiol Behav. 2011;103:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay DS, Woods SC. Biological consequences of drug administration: implications for acute and chronic tolerance. Psychol Rev. 1997;104:170–193. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richebe P, Rivat C, Creton C, Laulin JP, Maurette P, Lemaire M, Simonnet G. Nitrous oxide revisited: evidence for potent antihyperalgesic properties. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:845–854. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200510000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satinoff E. Neural organization and evolution of thermal regulation in mammals. Science. 1978;201:16–22. doi: 10.1126/science.351802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S. Tolerance to the hypothermic effect of morphine in the rat is a learned response. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1978;92:1137–1149. doi: 10.1037/h0077525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S. Drug anticipation and drug addiction. The 1998 H. David Archibald lecture. Addiction. 1999;94:1113–1124. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94811132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S, Baptista MAS, Kim JA, McDonald RV, Weise-Kelly L. Pavlovian Psychopharmacology: The associative basis of tolerance. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:276–293. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowska M, Siegel S, Kim JA. Intraadministration associations: conditional hyperalgesia elicited by morphine onset cues. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2002;28:309–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J. System properties, feedback control and effector coordination of human temperature regulation. European journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:13–25. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.