Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives

Associations between inflammation and ESRD and death in chronic kidney disease are well established. However, the potential role of the adaptive immune system is uncertain. We aimed to prospectively study the relevance of the adaptive immune system to ESRD and mortality by measuring monoclonal and polyclonal excesses of highly sensitive serum free light chains (sFLCs).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Three hundred sixty-four patients selected from a nephrology outpatient clinic had kappa and lambda sFLCs concentrations and serum immunofixation electrophoresis measured. Cox regression was used to assess the relevance of monoclonal and polyclonal excess of sFLCs to the incidence of ESRD and death (mean follow-up for death 6.0 years).

Results

After adjustment for baseline eGFR, there was no significant association between monoclonal excess of sFLCs and risk of ESRD or mortality. Baseline log κ and log λ concentrations were positively associated with ESRD risk, but these associations seemed to be due to correlations with eGFR (per 1 SD higher concentration: adjusted hazard ratio 1.05 [95% confidence interval 0.88 to 1.26] and 0.99 [0.83 to 1.19], respectively). For mortality, after adjustment for eGFR plus markers of cardiac damage, there was weak evidence of an association with λ, but not κ, sFLC concentration (fully adjusted hazard ratio 1.33 [95% confidence interval 1.05 to 1.67] per 1 SD higher concentration).

Conclusions

Associations between monoclonal and polyclonal excess of sFLCs and risk of ESRD are explained by the correlation between these measures and renal function. We found only weak evidence of an association between polyclonal excess of λ sFLC concentration and mortality.

Introduction

In Western populations, about 5% to 10% of the adult population has an estimated GFR (eGFR) less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (i.e., chronic kidney disease [CKD] stage 3 to 5) (1–3). These individuals are at increased risk of death (particularly from cardiovascular causes) and of progression to ESRD, compared with those without CKD (4,5). Reduced kidney function is associated with many factors that might be associated with increased risks of death, ESRD, or both (6).

The relationship between chronic inflammation and adverse outcome in CKD is well described, but work to date has principally evaluated the role of innate immunity in this relationship. Potentially, the activity of the adaptive immune system could also provide prognostic information in CKD. To evaluate this hypothesis, a sensitive measure of its activity is required.

As a consequence of normal (polyclonal) immunoglobulin production, about 500 mg/d of immunoglobulin free light chain (FLC) is released into the circulation (7) as one of two isotypes: a 22.5-kD kappa (κ) monomer or 45-kD lambda (λ) dimer. The concentration of these FLCs can be used to monitor the activity of the adaptive immune system, but the low levels found in the majority of individuals means that traditional techniques such as electrophoresis or immunofixation have inadequate sensitivity. The recent introduction of highly sensitive, quantitative immunoassays now allow the accurate quantification of serum FLC (sFLC) to below the lower limit of the normal range (8) and have also improved the diagnosis and assessment of people with monoclonal disease (9). Although the kidneys are frequently involved in monoclonal disease due to the direct effects of clonal sFLC (10), it is not known if intact (heavy chain) or light chain monoclonality without the presence of known clonal-specific end-organ injury (i.e., monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance [MGUS]) in people with CKD increases the risk of later ESRD or death.

In addition, the relevance of polyclonal sFLC to the natural history of CKD has not been assessed to date. This is an important issue because as the kidneys are the dominant route of sFLC clearance, there is a progressive increase in sFLC concentrations as kidney function declines (11). In people with CKD, reticuloendothelial clearance and therefore reticuloendothelial health becomes an important component of sFLC clearance. A further consideration is the presence of coincident inflammation, which will further elevate sFLC concentrations (12,13). Although sFLCs do have an immunomodulatory effect (14), there are no studies to date that have assessed their relationship to clinical outcomes in CKD.

Our aim therefore was to use a well characterized prospective cohort with robust long-term follow-up to assess the relationship between MGUS and polyclonal sFLC, and the risk of death and ESRD in people with CKD.

Materials and Methods

Details of the design and methods of the Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham (CRIB) study have been described previously (15–17) and are summarized below.

Recruitment and Eligibility Criteria

Individuals with serum creatinine >130 μmol/L but not receiving renal replacement therapy were recruited from the renal outpatient department at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham. Ethics approval was obtained from the South Birmingham Local Research Ethics Committee, and all participants provided written consent to participate.

Baseline Assessment

At the baseline assessment interview, research nurses recorded past medical history, current medication, and other relevant characteristics (smoking status, height, waist and hip circumference, weight, and BP). A 12-lead electrocardiogram was recorded, and urine and nonfasting blood samples were collected. Blood was separated by centrifugation (3000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes) within 60 minutes and stored in aliquots of 500 μl at −80°C.

In addition to the assays described previously (18), serum FLCs were measured on frozen samples collected at the baseline assessment by nephelometry, on a Dade-Behring BN II Analyzer, using particle-enhanced, high-specificity, homogeneous immunoassays (Freelite; The Binding Site, Birmingham, United Kingdom) (19). The assay sensitivity was 1 mg/L (20). The reference range for the κ/λ ratio was 0.37 to 3.17 (as determined in a patient population with severe acute kidney injury due to FLCs) (21). Serum electrophoresis with immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) was performed on all samples. Monoclonal gammopathy was defined as the presence of a monoclonal M-band on IFE and/or an abnormal κ/λ ratio (i.e., outside the reference range). Serum creatinine was measured by the Jaffe reaction, and the eGFR was calculated using the simplified MDRD equation (22). Within- and between-batch coefficients of variation were <10% for all assays.

Follow-up

Participants were flagged for mortality at the Office for National Statistics (United Kingdom), which provided the date and cause of all deaths occurring up to July 1, 2006. The development of ESRD (defined as the requirement for maintenance dialysis or receipt of a kidney transplant) was tracked through hospital and dialysis unit records up to the end of 2007. For ESRD, participants who did not reach ESRD were censored at their date of death or the date at which they were last known to be alive and ESRD-free. For mortality, participants not known to have died by July 1, 2006, were censored on that date.

Statistical Analyses

Where needed, continuous variables were normalized using log transformation. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the average age- and gender-adjusted relevance to ESRD and mortality risk of monoclonal gammopathy status (present or absent), log κ, log λ, and various combinations of κ and λ (the logarithms of their ratio and sum). To explore the extent to which any associations may be due to confounding by underlying baseline renal function, these analyses were then further adjusted for baseline eGFR and, for mortality, for smoking, elevated troponin, and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) concentration (three factors previously shown to be strong predictors of mortality in this cohort) (18). In figures, adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for each sixth of the distributions and plotted against average values in each group. These HRs are presented as “floating absolute risks,” which do not alter their values but merely ascribe an appropriate variance to the log of the HR in every group (including the reference group with HRs 1.0) (23). Formal tests for log-linearity were done by including a quadratic term in the regression model (other tests for nonlinearity were not performed). To assess whether the average relative risks (as estimated by the hazard ratios from the Cox model) seen during the follow-up period might vary in magnitude during follow-up, the proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model was formally tested by examination of the Schoenfeld residuals.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population

Between December 1997 and September 1999, 382 participants with stage 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease were recruited. Three hundred sixty-four of these patients were included in this analysis: 15 patients were excluded because of missing sFLC values and three patients were excluded because of a prior (one patient) or subsequent (two patients) diagnosis of myeloma. No patients in this cohort had other paraprotein-related kidney diseases. Thirty-five patients had an monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS+): 28 patients had an abnormal κ/λ ratio at baseline, two patients had a paraprotein evident on IFE, and five patients had both. Three hundred twenty-nine patients had a normal κ/λ ratio and no paraprotein on serum immunofixation (MGUS−). The baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1, and results of laboratory assays performed on baseline samples are shown in Table 2. Allowing for the number of comparisons performed, the only baseline characteristic that differed significantly between the two groups was the lower hemoglobin in the MGUS+ group (12.2 versus 10.6 g/dl; P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in baseline renal function or cardiac damage (i.e., troponin T or NT-proBNP) between the MGUS+ and MGUS− groups. Both kappa and lambda concentrations were significantly related to several baseline clinical and laboratory measurements (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), but several of these associations were explained in large part by their association with eGFR (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics in the CRIB cohort

| Completeness of data | All | MGUS status |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGUS− | MGUS+ | ||||

| Number of people | 364 | 329 | 35 | ||

| Age, years | 100% | 61.2 (14.4) | 60.9 (14.4) | 64.1 (13.9) | 0.21 |

| Estimated GFRa, ml/min/1.73m2 | 100% | 21.9 (10.7) | 22.1 (10.8) | 20.8 (10.2) | 0.49 |

| Number (%) of men | 100% | 236 (64.8%) | 212 (64.4%) | 24 (68.6%) | 0.63 |

| Disease history | |||||

| Vascular disease | 100% | 161 (44.2%) | 142 (43.2%) | 19 (54.3%) | 0.21 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 100% | 64 (17.6%) | 58 (17.6%) | 6 (17.1%) | 0.94 |

| Left Ventricular Hypertrophyb | 96% | 68 (19.5%) | 58 (18.4%) | 10 (30.3%) | 0.10 |

| Renal diagnosis | |||||

| Glomerulonephritis | 100% | 90 (24.7%) | 81 (24.6%) | 9 (25.7%) | 0.98c |

| Diabetes | 100% | 30 (8.2%) | 28 (8.5%) | 2 (5.7%) | – |

| Hypertension | 100% | 52 (14.3%) | 47 (14.3%) | 5 (14.3%) | – |

| Cystic disease | 100% | 29 (8.0%) | 27 (8.2%) | 2 (5.7%) | – |

| Obstructive/pyelonephritis | 100% | 31 (8.5%) | 28 (8.5%) | 3 (8.6%) | – |

| Other known cause | 100% | 47 (12.9%) | 41 (12.5%) | 6 (17.1%) | – |

| Unknown/unavailable | 100% | 85 (23.4%) | 77 (23.4%) | 8 (22.9%) | – |

| Medication | |||||

| Any antihypertensive | 100% | 301 (82.7%) | 274 (83.3%) | 27 (77.1%) | 0.36 |

| Aspirin | 100% | 95 (26.1%) | 87 (26.4%) | 8 (22.9%) | 0.65 |

| Vitamin D | 100% | 128 (35.2%) | 117 (35.6%) | 11 (31.4%) | 0.63 |

| Calcium | 100% | 83 (22.8%) | 73 (22.2%) | 10 (28.6%) | 0.39 |

| Iron | 100% | 94 (25.8%) | 86 (26.1%) | 8 (22.9%) | 0.67 |

| Erythropoietin | 100% | 35 (9.6%) | 30 (9.1%) | 5 (14.3%) | 0.32 |

| Folic acid/B Vitamins | 100% | 45 (12.4%) | 40 (12.2%) | 5 (14.3%) | 0.72 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 100% | 135 (37.1%) | 124 (37.7%) | 11 (31.4%) | 0.16c |

| Ex | 100% | 183 (50.3%) | 167 (50.8%) | 16 (45.7%) | – |

| Current | 100% | 46 (12.6%) | 38 (11.6%) | 8 (22.9%) | – |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 100% | 318 (87.4%) | 288 (87.5%) | 30 (85.7%) | 0.26c |

| Black | 100% | 22 (6.0%) | 18 (5.5%) | 4 (11.4%) | – |

| Asian | 100% | 24 (6.6%) | 23 (7.0%) | 1 (2.9%) | – |

| Physical measurements | |||||

| Weight, kg | 99% | 76.1 (16.6) | 76.1 (16.6) | 76.8 (16.3) | 0.79 |

| Height, m | 100% | 1.69 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.09) | 0.84 |

| Waist:hip ratio | 97% | 0.90 (0.11) | 0.90 (0.11) | 0.91 (0.07) | 0.76 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 99% | 26.6 (5.0) | 26.6 (5.0) | 26.8 (4.7) | 0.84 |

| SBP, mmHg | 99% | 151.1 (21.9) | 151.4 (22.0) | 148.4 (20.8) | 0.45 |

| DBP, mmHg | 99% | 83.8 (11.6) | 83.7 (11.9) | 84.2 (9.4) | 0.82 |

Values are mean with ±SD in parentheses or number of subjects with percentage (%) in parentheses. CRIB, Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance, defined in this table as the presence of a monoclonal M-band on immunofixation electrophoresis and/or a serum free light chain ratio <0.37 or >3.17.

GFR was estimated using the simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation. Individuals receiving renal replacement therapy at baseline (either dialysis or a renal transplant) were excluded from the study.

Based on an electrocardiographic study.

Single test across all groups.

Table 2.

Baseline laboratory values in the CRIB cohort

| Completeness of data | All | MGUS status |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGUS− | MGUS+ | ||||

| Number of people | 364 | 329 | 35 | ||

| Kidney function | |||||

| Creatinine, umol/L | 100% | 263 (192–403) | 262 (190–402) | 283 (210–431) | 0.63 |

| Cystatin C, mg/L | 95% | 3.0 (2.1–4.0) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) | 3.3 (2.7–4.1) | 0.12 |

| Urinary albumin:creatinine ratio, mg/mmoL | 80% | 56.9 (10.1–145.6) | 56.2 (10.1–147.6) | 62.0 (10.2–124.2) | 0.75 |

| Symmetric dimethylarginine, umol/L | 100% | 1.39 (1.06–1.92) | 1.37 (1.03–1.92) | 1.50 (1.25–1.99) | 0.41 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 100% | 18.9 (8.9) | 18.8 (8.9) | 19.6 (8.2) | 0.64 |

| Urate, umol/L | 96% | 448 (117) | 447 (119) | 458 (94) | 0.58 |

| Cardiac damage | |||||

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, ng/L | 100% | 532 (238–1882) | 519 (240–1799) | 629 (180–2843) | 0.62 |

| Number with elevated troponin T (>=0.01 μg/L) | 100% | 81 (22.3%) | 70 (21.3%) | 11 (31.4%) | 0.17 |

| Endothelial function | |||||

| Asymmetric dimethylarginine, umol/L | 100% | 0.52 (0.46–0.58) | 0.52 (0.45–0.58) | 0.53 (0.48–0.62) | 0.12 |

| Arginine, umol/L | 100% | 178 (152–202) | 179 (152–203) | 169 (147–190) | 0.33 |

| Von Willebrand factor, IU/dl | 92% | 142 (31) | 141 (31) | 150 (39) | 0.14 |

| Lipids | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 96% | 5.62 (1.27) | 5.63 (1.27) | 5.55 (1.31) | 0.73 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 79% | 1.26 (0.41) | 1.26 (0.41) | 1.24 (0.50) | 0.79 |

| Inflammation & nutrition | |||||

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 94% | 4.34 (1.35–9.69) | 4.36 (1.33–9.53) | 3.97 (1.74–13.00) | 0.65 |

| Albumin, g/L | 100% | 41.7 (4.5) | 41.8 (4.4) | 40.8 (5.1) | 0.22 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 89% | 3.48 (0.80) | 3.47 (0.79) | 3.56 (0.87) | 0.53 |

| Interleukin 6, ng/L | 90% | 3.9 (2.1–7.9) | 3.9 (2.1–7.8) | 4.5 (2.3–9.1) | 0.59 |

| Tumour necrosis factor-alpha, ng/L | 97% | 17.0 (5.5) | 17.0 (5.3) | 17.1 (6.7) | 0.93 |

| Calcium and phosphate homeostasis | |||||

| Calcium, mmol/L | 100% | 2.34 (2.26–2.43) | 2.34 (2.26–2.43) | 2.30 (2.18–2.39) | 0.11 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 96% | 1.36 (1.18–1.59) | 1.36 (1.18–1.58) | 1.36 (1.18–1.67) | 0.91 |

| 25 hydroxy vitamin D3, nmol/L | 95% | 43.9 (28.7–57.8) | 44.2 (29.7–58.0) | 33.3 (21.9–48.1) | 0.02 |

| 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3, pmol/L | 88% | 61.9 (43.8–82.2) | 62.5 (46.0–83.2) | 48.0 (36.4–70.2) | 0.01 |

| Intact parathyroid hormone, pmol/L | 86% | 14.5 (8.0–24.6) | 13.8 (7.5–24.2) | 20.8 (12.0–30.6) | 0.11 |

| Whole parathyroid hormone, pmol/L | 90% | 7.9 (4.5–13.8) | 7.4 (4.4–13.4) | 10.9 (6.9–16.3) | 0.04 |

| B vitamins | |||||

| Serum folate, nmol/L | 94% | 16.5 (11.3–25.8) | 16.5 (11.3–25.8) | 15.9 (11.1–27.2) | 0.95 |

| Red cell folate, nmol/L | 88% | 487 (374–698) | 488 (367–707) | 433 (390–671) | 0.82 |

| Vitamin B12, pmol/L | 94% | 333 (241–441) | 331 (245–436) | 349 (225–460) | 0.90 |

| Homocysteine, umol/L | 99% | 20.3 (15.8–26.3) | 19.9 (15.5–25.5) | 24.2 (18.6–30.2) | 0.03 |

| Rheological markers | |||||

| Soluble P selectin, ug/L | 91% | 55.0 (45.0–75.0) | 55.0 (45.0–75.0) | 57.0 (47.5–76.5) | 0.48 |

| Haemoglobin, g/dl | 97% | 12.1 (2.0) | 12.2 (2.0) | 10.6 (1.9) | <0.001 |

Values are mean with ±SD or median with interquartile range in parentheses or the number of subjects with percentage (%) in parentheses. CRIB, Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham study; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance, defined in this table as the presence of a monoclonal M-band on immunofixation electrophoresis and/or an serum free light chain ratio <0.37 or >3.17; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

GFR was estimated using the simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation. Individuals receiving renal replacement therapy at baseline (either dialysis or a renal transplant) were excluded from the study.

During a mean of 4.1 years' (1493 person-years) follow-up for renal events, 177 participants reached ESRD (mean rate: 11.9% per annum; Table 3). During a mean of 6.0 years' (2191 person-years) follow-up for mortality, 143 participants died (mean rate: 6.5% per annum; Table 3), of whom 67 (39%) had reached ESRD before death (data not shown).

Table 3.

Incidence of End-Stage Renal Disease and death in the CRIB cohort

| All | MGUS status |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MGUS− | MGUS+ | ||

| Number of people | 364 | 329 | 35 |

| End stage renal disease | |||

| Total person-years | 1493 | 1365 | 128 |

| ESRD | 177 (11.9% p.a.) | 154 (11.3% p.a.) | 23 (18.0% p.a.) |

| Mortality | |||

| Total person-years | 2191 | 1993 | 197 |

| Vascular | 71 | 66 | 5 |

| Non-vascular | 68 | 59 | 9 |

| Unknown | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| All-cause mortality | 143 (6.5% p.a.) | 129 (6.5% p.a.) | 14 (7.1% p.a.) |

ESRD, End stage renal disease; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance, defined as the presence of a monoclonal M-band on immunofixation electrophoresis and/or a serum free light chain ratio <0.37 or >3.17.

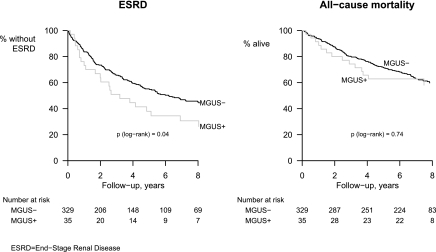

Associations of ESRD and Death with Monoclonal Gammopathy

During follow-up, 23 of 35 patients who were classified as MGUS+ at baseline and 154 of 329 patients who were classified as MGUS− at baseline developed ESRD (annual rates 18.0% and 11.3%, respectively; Table 3). This excess associated with MGUS+ represented an age- and gender-adjusted relative risk of 1.70 (95% CI 1.09 to 2.65; Table 4 and Figure 1). Upon further adjustment for baseline eGFR, this association was reduced to 1.39 (95% CI 0.90 to 2.17).

Table 4.

Relative hazard of ESRD and all-cause mortality associated with MGUS status, ln kappa, ln lambda, and two composite indices of kappa and lambda, before and after adjustment for age, gender, and eGFR and, for mortality, three other predictors of mortality (NT-proBNP, troponin, and cigarette smoking)

| Endpoint, level of adjustment | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGUS | Ln kappa (per 1 SD) | Ln lambda (per 1 SD) | Ln (kappa/lambda) (per 1 SD) | Ln (kappa + lambda) (per 1 SD) | |

| ESRD | |||||

| Age and sex | 1.70 (1.09, 2.65) | 1.77 (1.61, 1.95) | 2.14 (1.85, 2.49) | 1.14 (1.02, 1.27) | 1.90 (1.71, 2.11) |

| Age, sex and ln eGFR | 1.39 (0.90, 2.17) | 1.05 (0.88, 1.26) | 0.99 (0.83, 1.19) | 1.06 (0.90, 1.24) | 1.05 (0.87, 1.26) |

| Death | |||||

| Age and sex | 0.91 (0.52, 1.58) | 1.36 (1.18, 1.57) | 1.69 (1.42, 2.00) | 0.82 (0.67, 1.01) | 1.46 (1.26, 1.69) |

| Age, sex and ln eGFR | 0.95 (0.54, 1.65) | 1.16 (0.95, 1.42) | 1.52 (1.23, 1.89) | 0.74 (0.59, 0.92) | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) |

| Age, sex, ln eGFR, ln NT-proBNP, elevated troponin and smoking | 0.89 (0.51, 1.57) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31) | 1.33 (1.05, 1.67) | 0.77 (0.61, 0.96) | 1.15 (0.92, 1.44) |

MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance, defined in this table as the presence of a monoclonal M-band on immunofixation electrophoresis and/or an sFLC ratio <0.37 or >3.17. Estimated GFR, eGFR; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

Figure 1.

Time to End Stage Renal Disease and death in the CRIB study, by monoclonal gammopathy status.

During follow-up, 14 patients who were MGUS+ at baseline and 129 patients who were MGUS− at baseline died (annual rates: 7.1% and 6.5%, respectively; Table 3). This small difference reflected a nonsignificant age- and gender-adjusted relative risk of 0.91 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.58; see Table 4 and Figure 1) between the two groups. Further adjustment for eGFR or for other predictors of mortality had little effect on this association (Table 4).

There was no evidence that the average relative risks of ESRD or death associated with MGUS status varied over time (both tests for nonproportionality nonsignificant).

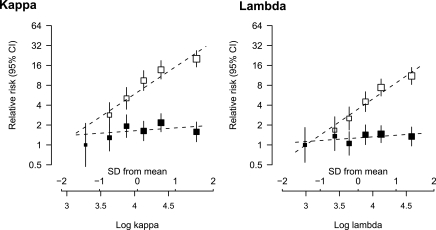

Associations of ESRD and Death with Polyclonal sFLC Concentrations

Both log κ and log λ sFLC concentrations were significantly and positively associated with an increased risk of ESRD in age- and gender-adjusted analyses (per 1 SD higher baseline level: HRs 1.77, 95% CI 1.61 to 1.95; and 2.14, 95% CI 1.85 to 2.49, respectively; see Table 4 and Figure 2). Upon further adjustment for baseline eGFR, these associations were significantly and substantially shifted toward the null (HRs 1.05, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.26; and HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.19, respectively; see Table 4 and Figure 2), with 95% CIs that precluded a large (>30%) increase in risk for a 1 SD higher concentration.

Figure 2.

Age- and gender-adjusted relative risk of ESRD associated with log kappa and log lambda before (white squares) and after (black squares) further adjustment for eGFR.

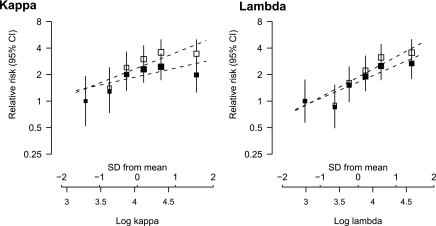

Log κ and log λ sFLC concentrations were also positively associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (age- and gender-adjusted HRs: 1.36, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.57; and 1.69, 95% CI 1.42 to 2.00, respectively; see Table 4 and Figure 3). After further adjustment for eGFR, the association with log κ sFLC concentration was markedly reduced and was no longer statistically significant (HR 1.16; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.42), but the association with log λ sFLC concentration remained (HRs 1.52; 95% CI 1.23 to 1.89). When three further characteristics (smoking, troponin T, and NT-proBNP) that were strongly associated with mortality in this cohort in a separate analysis were included in the model (18), this relative risk for log λ sFLC concentration was attenuated further but remained conventionally significant (HR 1.33; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.67). To examine this further, deaths were split into vascular and nonvascular causes. Of the 143 deaths, 71 were due to vascular causes, 68 were due to nonvascular causes, and four patients died of an unknown cause. Similar associations were seen between log λ sFLC concentration and vascular mortality as were seen between log λ FLC concentration and nonvascular mortality (fully adjusted HRs 1.26 [95% CI 0.90 to 1.75] and 1.35 [0.97 to 1.89], respectively). The positive association between log λ and mortality resulted in an inverse association being seen between the log κ/λ ratio and mortality (Table 4). Although the total sFLC concentration was associated with both renal progression and death in analyses adjusted only for age and gender (HRs 1.90 [95% CI 1.71 to 2.11] and 1.46 [ 95% CI 1.26 to 1.69], respectively), after adjustment for renal function and markers of cardiac damage the associations became nonsignificant (see Table 4).

Figure 3.

Age- and gender-adjusted relative risk of mortality associated with log kappa and log lambda before (white squares) and after (black squares) further adjustment for eGFR.

There was no evidence that the average relative risks of ESRD or death associated with log κ or log λ sFLC concentrations (or combinations of these measures) varied over time (all tests for nonproportionality nonsignificant) and no evidence of any (quadratic) nonlinear risk relationships. In addition, using the standard reference range for the κ/λ ratio (i.e., 0.26 to 1.65) instead of the “renal” reference range (21) had no effect on our conclusions (see Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This is the first prospective study of the association between both monoclonal gammopathy and sFLC concentrations with subsequent ESRD or death in a population of patients with CKD. The cohort is typical of a referred population and previous analyses have yielded risk scores that could be used to estimate the risk of ESRD or death in similar populations (18). Given the previous utility of this dataset, the present analysis should provide a reliable estimate of the risks associated with sFLC concentrations. After adjustment for baseline eGFR, we found no significant association between either the presence of a monoclonal gammopathy or κ or λ sFLC concentrations and risk of ESRD and only weak evidence of an association between λ sFLC concentration and mortality.

Monoclonal Gammopathy of Uncertain Significance

MGUS is defined as a serum paraprotein <3 g/dl, <10% plasma cells in the bone marrow, and no clinical manifestations of end-organ damage secondary to a monoclonal protein. The presence of both renal impairment and anemia in many of the patients in this study prevents absolute exclusion of a monoclonal protein causing or contributing to the CKD. First, all patients had significant renal impairment and second, the 35 patients with a monoclonal gammopathy had an average hemoglobin of 10.6 g/dl (compared with 12.2 g/dl in patients without a monoclonal gammopathy). However this cohort had long-term follow-up, and all patients who had or subsequently developed overt monoclonal disease were excluded (one patient with a diagnosis of myeloma before baseline and two patients who were diagnosed with myeloma during follow-up). There were no patients with other known paraprotein-related kidney diseases in this dataset.

The inclusion of sFLC concentrations with standard serum and urine electrophoresis and immunofixation in the diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathies is increasingly common, but may be complicated by the presence of renal impairment (24). The specificity of a “normal” (i.e., 0.26 to 1.65) κ/λ ratio has been reported to be unaffected by renal impairment (20,25), but few patients with renal impairment were included in these studies. Other authors have noted an increased false-positive rate and have recommended a wider reference range (21,26), as was used in this analysis. In the general population an abnormal κ/λ ratio occurs in about one third of all MGUS cases and is associated with a worse prognosis (27).

Overall, 35 of 364 (9.6%) of the CRIB cohort had a monoclonal gammopathy. This compares to 4.2% of the Olmsted County cohort (selected on the basis of being aged over 50 yeas old) (28). In the CRIB cohort 28 of 35 (80%) patients had light-chain only monoclonal gammopathy (LC MGUS), whereas in Olmsted County 146 of 769 (19%) of those with any monoclonal gammopathy had LC MGUS. However, the relevance of this finding is difficult to interpret. In this study the renal range has been utilized, and this may have excluded some people who would have been classified under the Mayo clinic definition as having LC MGUS.

The presence of a monoclonal gammopathy was associated with an increased risk of ESRD in age- and gender-adjusted analyses, but adjustment for renal function rendered this association nonsignificant. However, the point estimate was 1.39 and with only 35 patients in the group it remains possible that MGUS does increase the risk of ESRD in people with CKD. Interestingly, the Mayo Clinic group showed that almost 10% of the 0.8% of the general population who have LC MGUS (according to their definition) have known renal disease, and about 15% develop it subsequent to the diagnosis of MGUS. However, the presence of LC MGUS did not appear to increase the risk of subsequent kidney disease, whereas any MGUS (IFE or light-chain only) was reported to increase the risk of subsequent kidney disease (28). This relationship was not seen in the present study.

A monoclonal gammopathy was not significantly associated with an increased risk of death in age- and gender-adjusted analyses, although the CI could not exclude a real increase in risk existing of up to 50% (due to relatively few deaths occurring among patients with MGUS). Indeed, other research has shown that patients with MGUS are more likely to die of an unrelated disease than from progression of their gammopathy to a disease phenotype (29). This would be especially true in this cohort where the advanced nature of the renal disease puts them at a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality, especially cardiovascular disease (4,5), than patients with MGUS and preserved renal function. Certain diseases associated both with a monoclonal gammopathy and shortened survival (e.g., myeloma, primary amyloidosis, and light chain deposition disease) were not represented in this cohort, suggesting that they are uncommon enough not to significantly affect the relationship between a monoclonal gammopathy and outcome in the referred CKD population.

Polyclonal Gammopathy

Neither polyclonal excess of κ nor λ FLCs (or total sFLC concentration) was associated with an excess risk of ESRD once eGFR was taken into account. Such elevations are very common in a wide variety of inflammatory and infectious diseases, which are not frequently associated with renal impairment (12). Conceptually there are two principal reasons why polyclonal sFLCs could have been associated with progressive renal disease. First, excessive sFLC endocytosis by proximal tubular cells (PTCs) can induce a spectrum of inflammatory effects that include activation of redox pathways, nuclear factor–κB, and mitogen-activated protein kinases, leading to transcription of inflammatory and profibrotic cytokines, such as IL-6, MCP-1, IL-8, and TGF-β1 (30–36). Excessive FLC endocytosis can trigger apoptotic pathways and can also alter the PTC phenotype into fibroblasts through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Potentially, as renal function declines and hyperfiltration becomes significant, polyclonal FLCs could result in similar inflammatory cascades. Second, with reducing nephron mass, higher levels of FLCs are presented to the distal tubules and proteinaceous casts consisting of many proteins (including of κ and λ FLCs) are a frequent finding in renal pathology; whether they are causally related to progression of the primary renal disease is unclear. This cohort does not, however, provide epidemiologic data to support these hypotheses.

An association of sFLCs with reduced survival could either reflect the role of sFLCs as a marker of the activity of the adaptive immune system or sFLCs could represent a genuine pathogenic factor. The use of polyclonal sFLCs as a sensitive marker of adaptive immunity is particularly intriguing in light of the growing evidence for the important role of subclinical infections in determining the survival of CKD populations (37). Potentially, however, the role of sFLCs as uremic toxins explains why they could have a direct pathogenic role in the survival of a CKD population; polyclonal sFLCs can impair the function of neutrophils and hence impair the immune response (38). After adjustment for the three major baseline characteristics previously found to be associated with mortality in this cohort, a significant association for mortality remained for λ, but not κ, sFLC concentration. This discrepancy is difficult to explain as κ and λ FLCs have similar functions. It may, therefore, merely reflect the play of chance. If real, however, then it is possible that the magnitude of its association with mortality risk has been underestimated because of the use of baseline measurements in analyses (i.e., regression dilution bias) (39).

In this population the associations between λ sFLC concentration and both vascular and nonvascular mortality were similar. A causal relationship would be more plausible if the association was cause-specific, and residual confounding remains a possible explanation for this association.

The main limitation of this study is its relatively small size and the fact that the cohort was selected from a single clinic. However, our study population was broadly representative of the CKD population seen in U.K. nephrology clinics at the time, and whereas it may not be representative of the current CKD population seen in specialist clinics (which have a higher proportion of people with diabetes), this is unlikely to have much effect on the extent to which associations between sFLCs and the risk of ESRD and mortality can be explained by other characteristics.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the associations of MGUS and raised levels of polyclonal FLCs with progressive CKD and death were largely removed when adjustment for other factors was made. Only the association between λ sFLC concentration and mortality remained, and this appears likely to be artifactual. Analysis of these associations in larger cohorts may be helpful, but at present there does not appear to be an indication for the use of routine MGUS screening and sFLC quantification in the risk stratification of patients with CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These results were presented as a poster at the American Society of Nephrology, San Diego, California, 2009.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at www.cjasn.org

References

- 1. Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hallan SI, Dahl K, Oien CM, Grootendorst DC, Aasberg A, Holmen J, Dekker FW: Screening strategies for chronic kidney disease in the general population: Follow-up of cross sectional health survey. BMJ 333: 1047, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stevens PE, O'Donoghue DJ, de Lusignan S, Van Vlymen J, Klebe B, Middleton R, Hague N, New J, Farmer CK: Chronic kidney disease management in the United Kingdom: NEOERICA project results. Kidney Int 72: 92–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, McAlister F, Garg AX: Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2034–2047, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, Bacchetti P, Garg AX, Kaufman JS, Walter LC, Mehta KM, Steinman MA, Allon M, McClellan WM, Landefeld CS: Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2758–2765, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baigent C, Burbury K, Wheeler D: Premature cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. Lancet 356: 147–152, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Solomon A: Light chains of human immunoglobulins. Methods Enzymol 116: 101–121, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Katzmann JA, Abraham RS, Dispenzieri A, Lust JA, Kyle RA: Diagnostic performance of quantitative kappa and lambda free light chain assays in clinical practice. Clin Chem 51: 878–881, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hutchison CA, Basnayake K, Cockwell P: Serum free light chain assessment in monoclonal gammopathy and kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 621–628, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Basnayake K, Stringer SJ, Hutchison CA, Cockwell P: The biology of immunoglobulin free light chains and kidney injury. Kidney Int 79: 1289–1301, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hutchison CA, Harding S, Hewins P, Mead GP, Townsend J, Bradwell AR, Cockwell P: Quantitative assessment of serum and urinary polyclonal free light chains in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1684–1690, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solling K, Solling J, Romer FK: Free light chains of immunoglobulins in serum from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, chronic infections and pulmonary cancer. Acta Med Scand 209: 473–477, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gottenberg JE, Aucouturier F, Goetz J, Sordet C, Jahn I, Busson M, Cayuela JM, Sibilia J, Mariette X: Serum immunoglobulin free light chain assessment in rheumatoid arthritis and primary Sjogren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 66: 23–27, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen G: Immunoglobulin light chains in uremia. Kidney Int Suppl May: S15–S18, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landray MJ, Thambyrajah J, McGlynn FJ, Jones HJ, Baigent C, Kendall MJ, Townend JN, Wheeler DC: Epidemiological evaluation of known and suspected cardiovascular risk factors in chronic renal impairment. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 537–546, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Landray MJ, Wheeler DC, Lip GY, Newman DJ, Blann AD, McGlynn FJ, Ball S, Townend JN, Baigent C: Inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and platelet activation in patients with chronic kidney disease: The Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham (CRIB) study. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 244–253, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zehnder D, Landray MJ, Wheeler DC, Fraser W, Blackwell L, Nuttall S, Hughes SV, Townend J, Ferro C, Baigent C, Hewison M: Cross-sectional analysis of abnormalities of mineral homeostasis, vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in a cohort of pre-dialysis patients. The Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham (CRIB) study. Nephron Clin Pract 107: c109–c116, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Landray MJ, Emberson JR, Blackwell L, Dasgupta T, Zakeri R, Morgan MD, Ferro CJ, Vickery S, Ayrton P, Nair D, Dalton RN, Lamb EJ, Baigent C, Townend JN, Wheeler DC: Prediction of ESRD and death among people with CKD: The Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham (CRIB) prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 1082–1094, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, Tang LX, Showell PJ, Drayson MT, Drew R: Highly sensitive, automated immunoassay for immunoglobulin free light chains in serum and urine. Clin Chem 47: 673–680, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, Bryant S, Lymp JF, Bradwell AR, Kyle RA: Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: Relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem 48: 1437–1444, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hutchison CA, Plant T, Drayson M, Cockwell P, Kountouri M, Basnayake K, Harding S, Bradwell AR, Mead G: Serum free light chain measurement aids the diagnosis of myeloma in patients with severe renal failure. BMC Nephrol 9: 11, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Plummer M: Improved estimates of floating absolute risk. Stat Med 23: 93–104, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beetham R, Wassell J, Wallage MJ, Whiteway AJ, James JA: Can serum free light chains replace urine electrophoresis in the detection of monoclonal gammopathies? Ann Clin Biochem 44: 516–522, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vermeersch P, Van Hoovels L, Delforge M, Marien G, Bossuyt X: Diagnostic performance of serum free light chain measurement in patients suspected of a monoclonal B-cell disorder. Br J Haematol 143: 496–502, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hill PG, Forsyth JM, Rai B, Mayne S: Serum free light chains: An alternative to the urine Bence Jones proteins screening test for monoclonal gammopathies. Clin Chem 52: 1743–1748, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Bradwell AR, Clark RJ, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA: Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood 106: 812–817, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, Larson DR, Melton Iii LJ, Colby CL, Therneau TM, Clark R, Kumar SK, Bradwell A, Fonseca R, Jelinek DF, Rajkumar SV: Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: A retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet 375: 1721–1728, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blade J: Clinical practice. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 355: 2765–2770, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li M, Hering-Smith KS, Simon EE, Batuman V: Myeloma light chains induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 860–870, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pote A, Zwizinski C, Simon EE, Meleg-Smith S, Batuman V: Cytotoxicity of myeloma light chains in cultured human kidney proximal tubule cells. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 735–744, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sengul S, Zwizinski C, Batuman V: Role of MAPK pathways in light chain-induced cytokine production in human proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F1245–F1254, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sengul S, Zwizinski C, Simon EE, Kapasi A, Singhal PC, Batuman V: Endocytosis of light chains induces cytokines through activation of NF-kappaB in human proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int 62: 1977–1988, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang PX, Sanders PW: Immunoglobulin light chains generate hydrogen peroxide. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1239–1245, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ying WZ, Wang PX, Aaron KJ, Basnayake K, Sanders PW: Immunoglobulin light chains activate nuclear factor-kappaB in renal epithelial cells through a Src-dependent mechanism. Blood 117: 1301–1307, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Batuman V: Proximal tubular injury in myeloma. Contrib Nephrol 153: 87–104, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fisher MA, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW: Periodontal disease as a risk marker in coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 519–526, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cohen G, Haag-Weber M, Mai B, Deicher R, Horl WH: Effect of immunoglobulin light chains from hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients on polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions. J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1592–1599, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clarke R, Shipley M, Lewington S, Youngman L, Collins R, Marmot M, Peto R: Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol 150: 341–353, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.