Abstract

In order to scientifically apprise some of the anecdotal, folkloric, ethno medical uses of celosia argentea, the present study was undertaken to examine the antidiarrhoeal properties of alcoholic extract of leaves of Celosia argentea on diarrhoea by using different experimental models. Anti-diarrhoeal effect was evaluated by castor oil induced diarrhoea, charcoal meal test and PGE2 induced diarrhoea. Loperamide (2 mg/kg) and atropine (0.1mg/kg) were used as standard drugs. Extract was used in 100 and 200 mg/kg dose. It produced dose related anti-diarrhoeal effect. Results suggest that it may act centrally and may inhibit the PGE2 to give anti-diarrhoeal effects. Result of charcoal meal test also suggests its anti-muscarinic activity.

Keywords: Celosia argentea, castor oil diarrhoea, charcoal meal, PGE2

Introduction

Diarrhoea has long been recognized as one of the most important health problems in developing countries. It is defined as an increase in the frequency, fluidity, or volume of bowel movements and characterized by increased frequency of bowel sound and movement, wet stools, and abdominal pain. In clinical terms, it is used to describe increased liquidity of stools, usually associated with increased stool weight and frequency. In Nigeria, diarrhoea remains the number one killer disease among children aged 1-5 years, and worldwide the disease accounts for 4-5 million deaths among humans annually. Treatment of diarrhoea is generally non-specific and usually aimed at reducing the discomfort and inconvenience of frequent bowel movements. To overcome the menace of diarrhoeal diseases in developing countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included a programme for the control of diarrhoea, which involves the use of traditional herbal medicine. Several plants have been reported to be used in treating and managing diarrhoeal diseases[1].

On the contrary most of the herbal drugs reduce the offensive factors and proved to be safe, clinically effective, better patient tolerant, relatively less expensive, and globally competitive. Plant extracts, however, are some of the most attractive sources of new drugs and have been shown to produce promising results in the treatment of diarrhoea.

Celosia argentea possesses laxative, antioxidant[2], anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antibacterial activity. Celosia argentea exhibited antibacterial activity against a number of bacterial species[3]. Hepatoprotective effect of celosian was investigated by using liver injury models[4]. Celosia argentea is used in the traditional medicine for sores, ulcers, and skin eruptions[5]. However, detailed investigations of antidiarrheal activity of Celosia argentea had not been carried out so far. Hence, this leads us to study the antidiarrheal activity of Celosia argentea in different diarrhoeal models.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Albino Wister rats of both sex weighing between 150-250 g were used. Institutional Animal Ethics Committee approved the experimental protocol; animals were housed under standard conditions of temperature (24 ± 2°C) and relative humidity (30-70%) with a 12:12 light: dark cycle. The animals were given standard diet and water ad libitum. Animal handling was performed according to Good Laboratory Practice (GLP).

Plant Material

Leaves of Celosia argentea were collected from the Indore district. The dried leaves were powdered, and this powder was packed into soxhlet column and extracted with petroleum ether (60-80°C) for 24 h. The same marc was successively extracted with chloroform (50-60°C) and afterwards with ethanol for 24 h. The extracts were concentrated under reduced pressure. The dried extracts were stored in airtight container.

Drugs and Chemicals

Ethanolic solution of C. argentea was prepared in distilled water and was administered orally. Loperamide was procured from Micro Lab, Bangalore India.

Phytochemical analysis of the extracts

The extracts of Celosia argentea were subjected to qualitative analysis for the various phytoconstituents like alkaloids, carbohydrates, glycosides, phytosterols, saponins, tannins, proteins, amino acids and flavonoids[6,7].

Acute toxicity study

The acute oral toxicity study was carried out for alcoholic extract of Celosia argentea using fixed dose method according to OECD (1993) guideline no.420[8]. Healthy adult female Swiss albino mice weighing between 25 to 35 g were used for the study. Animals were divided into four groups of three animals each and fasted overnight. 5, 50, 300 and 2000 mg/kg b. w. doses were administered to the Group I,II,II,IV respectively. After administration of extracts various parameters like body temperature, CNS activity, micturation, defecation etc. were observed for 24 h.

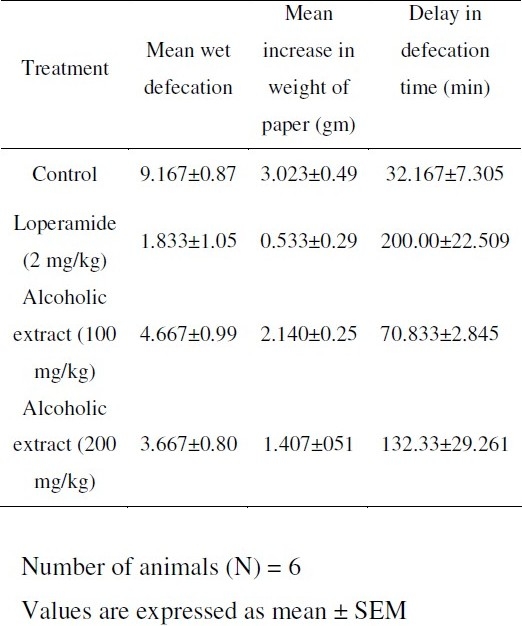

Evaluation of antidiarrhoeal activity Castor oil induced diarrhea[9]

Rats of either sex (150-250gm) were fasted for 18 h. They were divided into four groups (n=6). The first group, which served as control was administered with aqueous 1% tragacanth suspension. The second group received standard drug, Loperamide (2 mg/kg) orally as suspension. The extract was administered orally at 100 mg/kg dose to third group and 200 mg/kg dose to fourth group as suspension. After 60 min of drug treatment, the animals of each group received 1ml of castor oil orally and the watery faecal material and number of defecation was noted up to 4 h in the transparent metabolic cages with filter paper at the base. Weight of paper before and after defecation was noted.

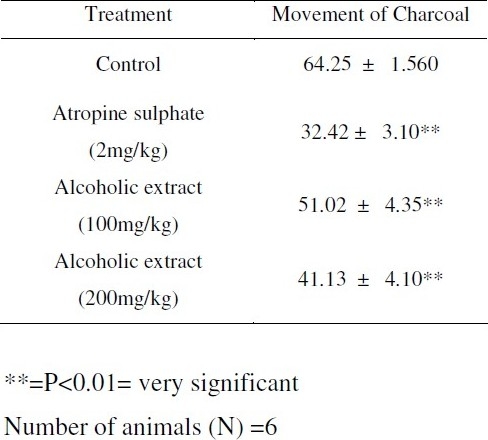

Charcoal meal test[10]

Rats of either sex (150-235 g) were fasted for 18 h. They were divided into four groups (n=6). The first group which served as control was administered with aqueous 1% tragacanth suspension. The second group receives standard drug atropine (0.1 mg/kg) subcutaneously. The extract was administered orally at 100 mg/kg to third group and 200 mg/kg to fourth group as suspension. The animals were given 1ml of 10% activated charcoal suspended in 10% aqueous tragacanth powder p.o., 30 min after treatment. Animals were euthanized 30 min after charcoal meal administration by ether anesthesia. The abdomen was cut off and the small intestine carefully removed. The distance travelled by charcoal plug from pylorus to caecum was measured, and expressed as percentage of the distance traveled by charcoal plug for each of animal.

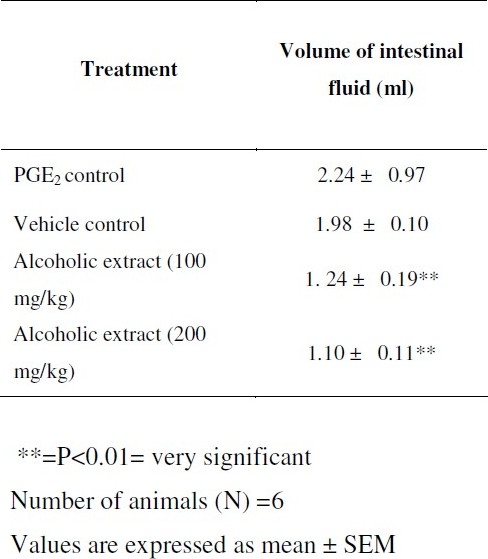

PGE2 induced enteropooling[11]

Rats of either sex (150-235 g) were fasted for 18h. They were then divided into four groups (n=6). A solution of PGE2 was made in the 5%v/v ethanol in the normal saline. The first group, which served as control, was administered with PGE2 (100 μg/kg p.o.) only. The second group, which served as vehicle control was administered with aqueous 1% tragacanth suspension by oral route. The extract was administered orally at 100 mg/kg to third group and 200 mg/kg to fourth group as suspension. Immediately after extract administration PGE2 was administered. After 30 min following administration of PGE2 each rat was sacrificed and whole length of the intestine from pylorus to caecum was dissected out, its content collected in measuring cylinder and volume measured.

Statistical analysis

The data are represented as mean ± S.E.M, and statistical significance between treatment and control groups was analysed using of one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnets test where P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

The acute oral toxicity study was carried out for alcoholic extract of Celosia argentea using fixed dose method according to OECD (1993) guideline no.420[8]. Healthy adult female Swiss albino mice weighing between 25 to 35 g were used for the study. Animals were divided into four groups of three animals each and fasted overnight. 5, 50, 300 and 2000 mg/kg b. w. doses were administered to the Group I,II,III,IV respectively. After administration of extracts various parameters like body temperature, CNS activity, micturation, defecation etc. were observed for 24 h.

Both doses of extract showed protection against PGE2 induced enteropooling, which might be due to the inhibition of synthesis of prostaglandins. Anti-enteropooling effect of the extract is more relevant because the prevention of enteropooling helps in the inhibition of diarrhea, especially by PGE2 induced diarrhea as it is involved in the onset of diarrhoea in intestinal mucosal cells. Although intraluminally administered PGE2 is known to induce duodenal and jejunal secretion of water and of electrolytes such as Cl and Na[12], fluid content is the principal determinant of stool volume and consistency. Net stool fluid content reflects a balance between luminal input (ingestion and secretion of water and electrolytes) and output (absorption) along gastrointestinal tract.

Neurohumoral mechanisms, pathogens and drugs can alter these processes, resulting in changes in either secretion or absorption of fluid by the intestinal epithelium. Altered motility also contributes in a general way to this process, as the extent of absorption parallels the transit time.

Alcoholic extract of Celosia argentea (100 and 200 mg/kg) and the anti-muscarinic drug, atropine (0.1 mg/kg) decreased the propulsive movement in the charcoal meal study, atropine being less potent than the aerial part extract of 200 mg/kg. The underlying mechanism appears to be spasmolytic and an anti-enteropooling property by which the extract produced relief in diarrhoea. Tannic acid and tannins are present in many plants and they denature proteins forming protein tannate complex. The complex formed coat over the intestinal mucosa and makes the intestinal mucosa more resistant and reduces secretion[13].

The tannin present in the plant extracts may be responsible for the anti-diarrhoeal activity.

The anti-diarrhoeal effect of the extracts may be related to an inhibition of muscle contractility and motility, as observed by the decrease in intestinal transit by charcoal meal and consequently, in a reduction in intestinal propulsion. Extract also inhibited the onset time and severity of diarrhoea induced by castor oil. Castor oil is reported to cause diarrhoea by increasing the volume of intestinal content by prevention of reabsorption of water. Castor oil contains ricinoleic acid which induces irritation and inflammation of the intestinal mucosa, leading prostaglandin release which, in turn, changes in mucosal fluid and electrolyte transport thereby preventing the reabsorption of NaCl and water results in a hypersecretory response and diarrhea[14,15,16]. The experimental studies in rats demonstrated a significant increase in the portal venous PGE2 concentration following oral administration of castor oil[17]. Ricinoleic acid markedly increased the PGE2 content in the gut lumen and also caused on increase of the net secretion of the water and electrolytes into the small intestine. Inhibitors of prostaglandin biosynthesis delayed castor oil induced diarrhea[18]. The diarrhoeal effect of castor oil may be involved NO[19,20] that increase the permeability of the epithelial layer to calcium ions, leading to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and enhancement of calmudin stimulation of NO synthatase activity. NO, in turn, could stimulate intestinal secretion. It is well known that nitric oxide and prostaglandins are crucial mediators contributing to generation of inflammatory response to castor oil. Alternatively, the effect of castor oil may be attributed to disordered motility and hence to an increase in intestinal transit of intraluminal material. In this connection, castor oil could alter coordination of intestinal motility and could promote greater loss of fluid from intestine[19]. The reduction of gastrointestinal motility is one of the mechanisms by which many anti--diarrhoeal agents act[21].

Conclusion

The antidiarrhoeal effect of ethanolic extract is due to reduction of gastrointestinal motility, inhibition of the synthesis of prostaglandin and NO. The extract has potential effect on the reduction of gastrointestinal motility than the other effects. The above effects of it may also be due to the presence of tannins and flavanoids in the extract.

Table 1.

Evaluation of anti-diarrhoeal activity of alcoholic extract of celosia argentea by castor oil induced diarrhoea

Table 2.

Evaluation of anti-diarrhoeal activity of alcoholic extract of celosia argentea by charcoal meal test

Table 3.

Evaluation of anti-diarrhoeal activity of alcoholic extract of celosia argentea by PGE2 induced enteropooling

References

- 1.Sani C.A, Dzenda T, Suleiman M.M. Antidiarrhoeal activity of the methanol stem-bark extract of Annona senegalensis Pers. (Annonaceae) J of Ethnopharmacology. 116:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olowoyo O.G, Adesina O.A, Adigun A.O, Azike C.K, et al. Pro- and antioxidant effects and cytoprotective potentials of nine edible vegetables in southwest Nigeria. J. of med. Food. 8:539–44. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiart C, Mogana S, Khalifah S. Fitoterapia Antimicrobial screening of plants used for traditional medicine in the state of perak. Vol. 75. peninsular Malaysia: pp. 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hase K, Kadota S, Basnet P, Takahashi T, Namba T. Protective effect of celosian, an acidic polysaccharide, on chemically and immunologicaly induced liver injuries. Pharma bull. 19(4):567–72. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulasekaran S Priya, Arumugam Ganamani, rathinam Bhuvaneswari. Celosia argentea Linn. Leaf extract improves wond healing in a rat burn wound model. Wound repair regeneration. 12(6):618–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khandelwal KR. Practical Pharmacognosy techniques and experiments. 9th ed. Pune (India): Nirali prakashan; 2007. pp. 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokate CK, Purohit AP, Gokhale SB. Pharmacognosy. 12th ed. Pune (India): Nirali Prakashan; 1999. pp. 323–325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organization for Economic cooperation and development (OECD) Guidelines for testing of chemicals Acute Oral Toxicity, OECD, No 420. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sairam K, Hemalatha S, Kumar A, Srinivasan T, Ganesh J, Shankar M. Venkataraman Evaluation of antidiarrhoeal activity in seed extracts of Mangifera indica. J Ethnopharmacology. 2003;84:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federica V, Giuseppina F, Antonella S, Beatrice T. Inhibition of intestinal motility and secretion by extracts of Epilobium spp. in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:342–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin J, Puckree T, Mvelase TP. Anti-diarrhoeal evaluation of some medicinal plants used by Zulu traditional healers. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:53–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rask-Madsen J, Bukhave K. The role of prostaglandins in diarrhea. In: Read N. W, editor. New Insights. London: Janssen Pharmaceutical; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tripathi KD. Essential of Medical pharmacology. 4thed. New Delhi: JP Publication; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ammon HV, Thomas PJ, Phillips S. Effects of oleic and recinoleic acids net jejunal water and electrolyte movement. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1974;53:374–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI107569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce NF, Carpenter CC, Elliot HL, Greenough WB. Effects of prostaglandins, theophylline and cholera exotoxin upon transmucosal water and electrolyte movement in canine jejunum. Gastroenterology. 1971;60:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaginella TS, Phillips SF. Ricinoleic acid; current view of ancient oil. Digestive Disease and Sciences. 1975;23:1171–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01070759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luderer JR, Dermers LN, Hayn AT. Advances in Prostaglandin and Thromboxane Research. New York: Raven Press; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awouters F, Neimegeers CJE, Lenaerts FM, Jansen PA. Delay of castor oil diarrhoea in rats; a new way to evaluate inhibitors of prostaglandin biosynthesis. J. Pharm Pharmacol. 1978;30:41–45. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1978.tb13150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izzo AA, Mascolo N, Capasso R, Germano MP, De Pasquale R, Capasso F. Inibitory effect of cannabinoid agonists on gastric emptying in the rat. Archieves of Pharmacology. 1999;360:221–223. doi: 10.1007/s002109900054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Carlo GD, Mascolo N, Izzo A.A, Capasso F. Effects of quercetin on the gastrointestinal tract in rats and mice. Phytother Res. 1994;8:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akah PA, Aguwa CN, Agu RU. Studies on the antidiarrhoeal properties of Pentaclethra macrophylla leaf extracts. Phytother Res. 1999;13:292–95. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199906)13:4<292::AID-PTR415>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]