Abstract

Sense of coherence (SOC), with its components comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness, is a major factor in the ability to cope successfully with stressors and is closely related to health. Qualitative studies related to SOC are scarce, and in this phenomenological interview study, self-care is investigated in relation to SOC. The aim of this study was to describe the lived experiences of self-care and features that may influence health and self-care among older home-dwelling individuals living in rural areas and who have a strong SOC. Eleven persons with a mean age of 73.5 years and a SOC value in the range of 153–188, measured by Antonovsky’s 29-item SOC scale, were interviewed. The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed with a phenomenological descriptive method. The findings showed that successful self-care involves having, when needed, contact with the health care system, being conscious of a sound lifestyle, being physically and mentally active, being engaged, having social contacts with family and/or others, and being satisfied and positive and looking forward. Formal and informal caregivers should be conscious of the importance of motivating and supporting older individuals with respect to these dimensions of self-care.

Keywords: aged, activity, contacts, phenomenology, well-being

Introduction

Studies among older people often focus on problematic areas in their daily living together with general or specific health deficiencies. To study the potentialities of older people may give us knowledge about how to preserve abilities and resources among a growing number of older individuals and thereby facilitate successful aging and postpone functional decline, self-care deficits, and health problems. This study reports findings from a phenomenological interview study among home-dwelling older people with a strong sense of coherence (SOC) living in rural areas in southern Norway.

A person’s SOC is considered an important factor in maintaining the individual’s position on the health ease/dis-ease continuum and in possible movement toward the healthy end of the continuum.1 The concept of SOC is built on factors that are, in all cultures, a basis for successful coping with stressors. A person with a strong SOC will find stimuli from the internal and external environments to be structured, predictable, and explicable, and they will have available resources to meet these stimuli and to consider the associated demands as challenges worthy of engagement and investment. Thus, three components that constitute the SOC concept can be outlined: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. To be able to measure a person’s SOC, the 29-item SOC scale (SOC-29) was developed. An individual’s total score on the scale can range between 29 and 203, with a higher score expressing a stronger SOC.1,2 Antonovsky2 has presented normative data from 21 different published studies where SOC-29 has been used. Mean SOC scores ranged from 117 (Czech cancer patients) to 152.6 (Swedish adults).2

According to Antonovsky,1 a person’s location on the SOC continuum is more or less fixed from early adulthood. Later studies have shown that SOC is not as stable as Antonovsky assumed.3 However, it seems to be most stable over time in people with an initial strong SOC. SOC tends also to increase with age – that is, older people tend to have a stronger SOC than younger people.3 A strong SOC has been found to contribute to quality of life in older people4–7 and to be a predictor for life satisfaction in both younger and older people.8 SOC is also an important determinant of perceived good health, both among older home-dwelling physically active persons and among older hospitalized patients.9,10 Healthy older people are more likely to report a stronger SOC than unhealthy older people.11 Furthermore, the SOC component comprehensibility has been shown to be a positive predictor for explaining health in older home-dwelling people.10 SOC is also considered as a major life orientation that focuses on problem solving.12,13 Since SOC is about resources for health and problem solving, it is conceptually related to self-care ability, which has been shown in a study among older patients at risk for undernutrition.14 SOC is also a significant predictor for self-care in older patients with chronic illness.15,16

When considering that SOC and self-care ability both focus on the person’s resources or potentiality for health, these two concepts can be investigated as separate concepts or in relation to each other. It should be important for formal and informal caregivers to support the actualization of the resources of older people in order to make it possible for this growing group in society to obtain health and well-being. However, little is known about the meaning of these health-related resources and their actualization. Although SOC is frequently used in studies with older people, it is mostly used as a descriptive quantitative variable,15,17–19 and no studies that can shed light on the meaning of having a strong SOC in relation to self-care have been found. The meaning of self-care may possibly also be associated with environmental factors,20 such as a rural or an urban environment.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the lived experiences of self-care and features that may influence health and self-care among older home-dwelling individuals living in rural areas and who have a strong SOC.

Method

Design

To study lived experiences, a phenomenological research approach was chosen. A descriptive phenomenological research method designed by Giorgi21,22 was used to analyze narrated lived experiences of self-care.

Study group

Informants were recruited among home-dwelling older people (65+ years) in rural areas who had participated in a survey study in southern Norway during the spring of 2010.23 Primarily, a theory-based sampling24 was conducted, and individuals having a strong SOC were selected. SOC was measured with SOC-29, which is a semantic differential questionnaire with high internal consistency and evidence of validity.1,2 In 26 studies from 20 different countries a Cronbach’s alpha value was found that ranged from 0.82 to 0.95. Also test-retest studies have shown that the scale has considerable stability.2 It was found in a study with SOC-29 by Söderhamn and Holmgren25 that the global concept SOC was hierarchically organized in a model that consisted of the three core components comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. This evidence of construct validity together with a number of other studies that were summarized by Antonovsky2 have shown that the scale has good psychometric properties and evidence of face validity, content validity, and construct validity.

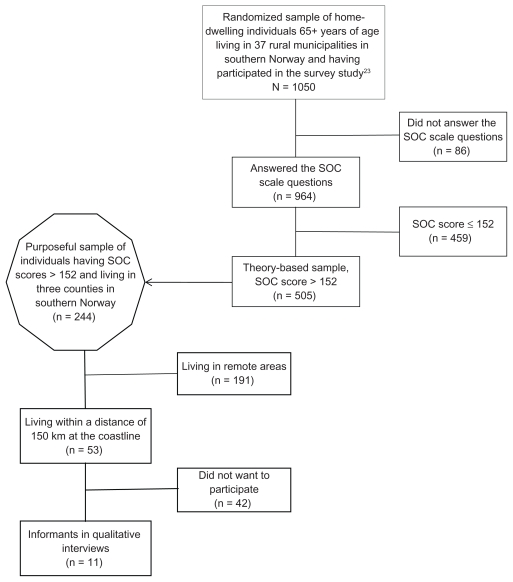

Since no official cutoff point is recommended for this type of sample in the literature, a SOC score ranging from 153 to 203 – that is, a value that was higher than the mean value of 152 in the survey study23 – was considered to be a strong SOC. This is also in line with normative data from other studies.2 Among the informants who had completed the SOC scale questions in the questionnaire (n = 964), a group of 505 individuals had a strong SOC according to this criterion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sample selection.

Abbreviation: SOC, sense of coherence.

Following this, a purposeful sampling24 was implemented among the individuals with a strong SOC who were living within a maximum travel distance of 150 km at the coastline in three different county councils. Fifty-three persons who satisfied these inclusion criteria were selected, and a letter with information about the study and a request for participation was distributed to them by mail. Forty-two persons did not want to participate in the study. Eleven persons, six men and five women with a mean age of 73.5 years, ranging between 67 and 89 years, agreed to participate and sent back a signed sheet that was considered as informed consent (Figure 1). Mean SOC score among the informants was 165.4, ranging between 153 and 188. They were contacted by telephone by the first author and an appointment was made regarding place and time for the interviews. The study was implemented between the autumn/winter of 2010 and the spring/summer of 2011.

The interviews

Ten of the informants were interviewed in their homes and one informant was interviewed in her office. Because lived experiences of self-care and features that may influence health and self-care were the focus in the interviews, it was crucial to let the informants narrate such experiences openly and freely. Therefore, the opening question was open and formulated as follows: “Please tell me about a situation you have experienced where you could maintain health and well-being.” Follow-up questions such as “Tell me more about that!”, “What did you mean with that?” and “How did you think about that?” were used for clarification or elaboration. The interviews, which lasted up to 50 minutes, were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The interview text was analyzed phenomenologically by means of the steps described by Giorgi.21,22 For Step 1 (Read for sense of the whole), the interview text was read from a phenomenological scientific reduction perspective in order to get a grasp of the sense of the entire description – that is, the meanings the informants had expressed. For Step 2 (Determination of meaning units), the text was demarcated into meaning units – that is, broken down into a series of meaning units. For Step 3 (Transformation of informant’s natural attitude expressions into the language of health science), each meaning unit, expressed in the informant’s own words, was transformed – that is, expressed in language revelatory of the health science aspect of the lived-through experience with respect to the self-care phenomenon studied. For Step 4 (Writing situated structures for each interview and a general structure), the transformed meaning units formed the basis for eleven situated structures that are meant to depict the lived experience of the studied phenomenon for each informant. The situated structures were then composed to a general structure based upon data from all informants and taking all imaginary variations into account. The general structure and the features this structure was found to be composed of will be presented in this article in the Results section.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in southern Norway as a part of a larger project on self-care and health among older home-dwelling people in rural areas in southern Norway (REK Sør-Øst D, 2009/1299). When designing and performing this study, the intentions of the Declaration of Helsinki26 and ethical standard principles27 were followed. Confidentiality was assured and the informants had the opportunity to withdraw without declaring their reasons.

Results

General structure of self-care

The general structure of self-care as lived experience among older home-dwelling individuals living in rural areas and who have a strong SOC was narrated as follows: Self-care is having, when needed, contacts with the health care system, being conscious of a sound lifestyle, being physically and mentally active, being engaged, having social contacts with family and/or others, and being satisfied and positive and looking forward.

Features that influence health and self-care

Having contacts with the health care system

When needed, the informants consulted the health care system because of different diseases. The informants perceived having access to a medical center with one’s own family doctor, to hospitals, and to care homes in the neighborhood as both fortunate and safe, but they perceived being able to be treated by skilled health care professionals as fortunate and safe as well. To have a good contact with the physician and to tailor a plan together with him or her for treatment that was adapted for the individual’s situation was perceived as important for good health. To be called to the physician for checkups and continuous visits was also perceived as an important safety measure. Moreover, to be observant when it came to symptoms and taking medicines was seen as a way to maintain health. The informants did not consider themselves as being ill. Even when having a serious disease such as cancer, it was possible to put away depressive feelings and go on. After surgery and treatment, everything was considered to be well again.

Being conscious of a sound lifestyle

Having a sound lifestyle was important for health and well-being. A sound lifestyle included being active and eating a healthy diet and avoiding excessive use of tobacco, alcohol, and sweets. Omega-3 or cod liver oil, calcium, and magnesium were examples of dietary supplements that informants used. The diet could vary, but the informants liked eating a lot of vegetables, fruit, berries, and fish. Eating dinner every day with different vegetables was prioritized, and having fish several times a week was often considered healthy. In the summer, gardens often provided berries and fruit. The informants realized that a low carbohydrate diet could regulate the blood glucose level and thereby decrease prescribed medications for individuals with diabetes. They saw home-baked bread as important for enabling a smooth bowel function, having a diet that could regulate the blood cholesterol level as essential when this was high, and not to eat too much and to avoid fat and sauce a way to keep weight down. However, to cook and eat good food was also a perceived source of health and well-being.

Being physically and mentally active

Being active was seen as a way to maintain health and well-being. To only sit down in a chair and do nothing was considered dangerous. Considerable importance was placed on being active. The intensity of the physical activity varied in relation to the condition and age of the individual and could vary between performing relatively demanding exercises – like Nordic walking, running, bicycling, wandering in mountains, working out on a treadmill in a training center, or doing weight training twice a week – to being moderately active by taking promenades. But doing physical work at home, such as keeping the house and garden in good shape or doing other domestic work, were also important activities that could yield physical exercise “for free.” Even as an amputee it was possible to walk and perform housework, with the help of different assistive devices. Being physically active was perceived to increase quality of life and give strength and energy.

However, it was also important to perform mental activities to maintain health and well-being. Examples of these mental activities include reading books and newspapers, following news and debates on TV, listening to the radio, reading news on the computer that was not viewed on TV, doing sudoku or crossword puzzles, writing a diary, writing down memories from past times on the computer, or performing genealogy research.

Being engaged

Being engaged and occupied by something was considered very valuable for feeling healthy. This engagement could involve working as a volunteer for other older people – those living in residential living and care homes. Such voluntary work consisted of visiting the aged; helping them; buying things for them; inviting them for a car ride; or baking, cooking, and arranging meals and music evenings for them. These kinds of activities were perceived as very valuable, because caring for others gave so much back to the volunteers. One of the informants expressed that being engaged with these older people made it possible to care for older people when one’s own parents were gone. Other expressions of this engagement were to arrange dancing evenings for older people and driving them by car to the venue and back home. Such arrangements could be arduous, but a feeling of pleasure compensated for this. Other activities were to organize journeys abroad. Being a board member or a usual member in different societies and unions according to one’s personal interests (eg, religious and political unions and patient interest organizations) was another way of being engaged. A result of having a personal Christian faith was a wish to share this faith with other people and to be engaged in Christian teaching in one’s own parish.

To get involved in the care of a mentally disabled child or a mother who had reached an advanced age could also be responsibilities that resulted in an engagement, and to have and perform such duties could contribute to a feeling of strength.

Having social contacts with family and/or others

The closest family and other social networks meant a lot to the informants for maintaining health and well-being. Having a good marriage and being able to share interests and hobbies with the spouse was valuable. A good relationship with the children was of importance, and it was nice to visit them, to have them to visit, and to arrange things for them. Spending time with grandchildren/great-grandchildren was a way to develop as people, and in particular, taking care of them helped to deepen their relationships with them. At the same time as experiencing their own pleasure in being with the small grandchildren, they could also be a help and relief for the grandchildren’s parents. One of the informants found it fun to help their own children with home maintenance and improvements and to provide carpentry and painting skills. For those older individuals who needed some help, their children assisted them. Examples of this included carrying home heavy loads of food after shopping or providing technical assistance with the computer.

Having friends was important to informants for health and well-being. Also, a cat, by being a very social creature, could be seen as a friend or a family member and thereby contribute a lot to health and well-being. Being a member in unions, organizations, or societies was a way of meeting people with the same interests and being together in different settings, such as for outings or trips away. Friends within the same age group and from the same local area could offer the possibility of talking about news in the community. A local senior café could be a natural meeting place for such local talks. If someone had lost a relative, the friends were very valued. It was important to have someone to talk to and also to do things together with, such as going to concerts or restaurants. The telephone also provided the possibility of getting in touch with friends or family. Writing letters was a way to keep in contact with friends living far away. However, for some of the informants, the computer was a major communication tool, providing access to Skype, e-mail, and Facebook and a very good way to view photographs.

Being satisfied and positive and looking forward

The informants saw being free and having the opportunity to do things that provided joy and allowed one to follow one’s own desires as very satisfying. However, to continue to work after retiring was also seen as very satisfying for one informant, and also to perform voluntary work. Feeling comfortable with the place of residence, the community, the apartment, or the house and enjoying the surroundings at home, at the cabin in the mountain, or in the boat were means to obtain and maintain personal health. To do something for oneself, such as decorating the home with flowers, dressing up in new clothes, going to the hairdresser, or having a pedicure, were also important to informants for feeling well. Being financially comfortable and being able to travel and see other cultures and meet other people were also considered attractive ways to feel good.

Being an optimist, having a positive view of life, being happy with one’s own situation, and feeling that one has a good life were all important for maintaining health and well-being. Even for those who go through tough experiences, such as seeing a child or spouses pass away, life must go on. Informants saw it as necessary to accept that some days can be gloomy, but also that it was important to avoid feeling sorry for oneself, because that makes things worse. Bad things have to be left behind. Life experiences, having a positive life view, and talking to friends and family can help people to handle difficult things in life, such as in the death of a loved one or contracting a serious disease. For example, to be left an orphan can make a person stronger and can thereby facilitate that person’s ability to tackle life. To have had a good childhood can also be a good base to build one’s life on. Having a Christian faith was also considered by informants to be a way to achieve good mental health, based on forgiveness: one can put things aside and get a new beginning.

For maintaining health and well-being, it was also important for the informants to have something to look forward to. Examples include having a journey to look forward to, to dream of new things to do, or to be hopeful for every day.

Discussion

This study focuses on self-care in a group of older people with a strong SOC, who could be expected to have great potentialities for self-care.14 Indeed, quite a positive picture of older individuals’ self-care agency is revealed in the obtained general structure of self-care.

Self-care is central in health care, and the concept may be defined as the means to maintain, restore, and improve health and well-being.28 When considered on a more general level, it could be seen as a fundamental goal for human beings to reach a high degree of self-care in order to obtain good health and a good life. Performed effectively, self-care contributes to human functioning, human structural integrity, and human development – that is, to a dynamic and holistic state of health.20 Good health and a good life for older people could in a sense be characterized as successful aging.

The obtained general structure of self-care reflects some aspects of the universal self-care requisites described by Orem.20 Examples of these include maintenance of a balance between activity and rest; maintenance of a balance between solitude and social interaction; prevention of hazards to human life, human function, and human well-being; as well as promotion of normalcy. It also, to some degree, reflects the components of the SOC concept: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness.1

Having contact with the health care system clearly reflects the components of self-care agency: (1) the capability to engage in self-care, (2) the estimative operations of self-care, and (3) the productive operations of self-care. These three components must stay together, and no one component can stay in isolation from the other two.20,29 Having regular checkups and visits to a family doctor or other physicians is a good way to prevent disease and also to have an eye on the onset of disability in daily living, functional decline, and reduced independence. Risk factors for functional decline are impaired physical and psychosocial health, cognitive impairment, environmental conditions, social circumstances, nutrition, and lifestyle.30 Although it is an expected part of aging to become more dependent,31 the informants in this study reflected positive feelings and tried to leave depressive feelings behind and look forward. Having higher expectations about aging has been shown to be associated with better physical and mental health.32 The theme about being conscious about a sound lifestyle also reflects issues closely related to the informants’ present and future health situations.

The older persons looked upon their bodies mainly in a detached and third-person way, as objective bodies – that is, as physical objects or bodies being-in-themselves.33 The objective body had its location in objective time and space, and having contact with the health care system when needed reflects both comprehensibility and manageability. It has been shown that comprehensibility and disease predict health among home-dwelling older individuals.10

The unarguable benefit of activities was a conscious issue among the informants. They saw both physical and mental activities as important for maintaining health and well-being, and being active has been shown to be a productive means for self-care among older home-dwelling people in other studies.23,34 This is also in line with a study among middle-aged individuals about their transition into retirement, where it was shown that participants saw old-age pensioner life, when being in good health, as a time of opportunities: retirement could give a sense of freedom and motivation for being active.35

It was also important for the informants in this study to be engaged – that is, mainly being engaged with other people and helping them out in different ways. This altruistic engagement was a source of pleasure that generated energy and personal satisfaction. Also, engagement with the closest family, children, grandchildren, and friends was a key issue in the lives of the informants in this study. This is congruent with the results from another study,36 where the meaning of actualizing self-care ability into self-care activity was interpreted as self-realization or self-transcendence. It is evident that helping other people can be considered meaningful, comprehensible, and also manageable for individuals with a strong SOC. This is also reflected in the theme of having social contacts. It may be possible that both engagement and the importance of social contacts are related to living in a rural environment and the possibilities of having quite robust social networks in such areas.

Feeling satisfied is another productive means for self-care according to an earlier study,34 and this was also narrated in the present study. Having a positive view of life, being an optimist, and looking forward all reflect the temporality in self-care for these persons, where the present and future were simultaneous.

In the present study, phenomenological thought guided the research that originally was based on the SOC concept, which in no way is connected to this philosophy. However, the concept did not interfere in the data collection or analyses of the interviews, and knowledge about self-care and health was bracketed.21,22 Although it is more or less impossible to completely implement the phenomenological reduction,37 the authors have tried not to contaminate the analyses with any knowledge other than what presented itself in the interview texts. By implementing the phenomenological reduction and by searching for essences in the text, the fundamental basis for validity in a phenomenological sense was obtained, and it could be claimed that the authors have defensible knowledge claims. When the same meaning in the narratives was consistently identified, reliability in the findings can also be discussed.38

In order to find manifestations of the SOC concept, the first step was to conduct a theory-based sampling. Since this group of individuals was too large to handle in a qualitative study, a purposeful sampling24 was implemented in the second step. Among those individuals who agreed to participate, a sufficient study group providing rich and varied narratives that could be analyzed phenomenologically according to Giorgi’s21,22 descriptive method was obtained. High credibility of the data from this group could also be expected.24 It seems reasonable that the findings from this study could be transferred to other groups of older people, living in other geographical areas, with good resources for maintaining health and well-being. However, the general structure of self-care found in this study group should not be seen as the definitive essence of the phenomenon; further research within a lifeworld paradigm is needed.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that the lived experiences of self-care for the older individuals living in rural areas and who have a strong SOC was related to the objective body and to social and psychological issues. It is reasonable to think that people with a strong SOC themselves are quite able to further develop the features that influence self-care and health in their own contexts. However, health care professionals should be conscious of the importance of motivating and supporting older individuals in their self-care regarding health promotion and health maintenance, disease prevention, detection, and management. Social contacts and networks together with positive attitudes toward life in general and to the future are other aspects manifested in the older individuals’ lived experiences that reflect comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. These aspects should be focused for formal and informal caregivers in order to facilitate successful aging.

Acknowledgments

The study was carried out with financial support from the Research Council of Norway (project number 18785). The informants are thankfully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):460–466. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borglin G, Jakobsson U, Edberg AK, Hallberg IR. Older people in Sweden with various degrees of present quality of life: their health, social support, everyday activities and sense of coherence. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(2):136–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekwall AK, Sivberg B, Hallberg IR. Older caregivers’ coping strategies and sense of coherence in relation to quality of life. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(6):584–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drageset J, Nygaard HA, Eide GE, Bondevik M, Nortvedt MW, Natvig GK. Sense of coherence as a resource in relation to health-related quality of life among mentally intact nursing home residents: a questionnaire study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:85. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norekvål TM, Fridlund B, Moons P, et al. Sense of coherence: a determinant of quality of life over time in older female acute myocardial infarction survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(5–6):820–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langeland E, Wahl AK, Kristoffersen K, Nortvedt MW, Hanestad BR. Sense of coherence predicts change in life satisfaction among home-living residents in the community with mental health problems: a 1-year follow-up study. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(6):939–946. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9199-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmgren L, Söderhamn O. Perceived health and well-being in a group of physically active older Swedish people. Vård i Norden/Nordic Journal of Nursing Research and Clinical Studies. 2005;25(3):39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Söderhamn O, Söderhamn U. Sense of coherence and health among home-dwelling older people. Br J Community Nurs. 2010;15(8):376–380. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.8.71945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilhooly M, Hanlon P, Cullen B, MacDonald S, Whyte B. Successful ageing in an area of deprivation: Part 2. A quantitative exploration of the role of personality and beliefs in good health in old age. Public Health. 2007;121(11):814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson G, Kallenberg KO. Sense of coherence, socioeconomic conditions and health: interrelationships in a nation-wide Swedish sample. Eur J Public Health. 1996;6(3):175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindström B, Eriksson M. Salutogenesis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):440–442. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.034777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Söderhamn U, Bachrach-Lindström M, Ek AC. Self-care ability and sense of coherence in older nutritional at-risk patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(1):96–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher R, Donoghue J, Chenoweth L, Stein-Parbury J. Self-management in older patients with chronic illness. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(5):373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warwick M, Gallagher R, Chenoweth L, Stein-Parbury J. Self-management and symptom monitoring among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(4):784–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forbes DA. Enhancing mastery and sense of coherence: important determinants of health in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2001;22(1):29–32. doi: 10.1067/mgn.2001.113532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neikrug SM. Worrying about a frightening old age. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(5):326–333. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000150702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nygren B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):354–362. doi: 10.1080/1360500114415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orem DE. Nursing: Concepts of Practice. 6th ed. St Louis (MO): Mosby Year Book; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giorgi A. Phenomenological and Psychological Research. Pittsburg (PA): Duquesne University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giorgi A. The Descriptive Phenomenological Method in Psychology: A Modified Husserlian Approach. Pittsburg (PA): Duquesne University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale B, Söderhamn U, Söderhamn O. Self-care ability among home-dwelling older people in rural areas in southern Norway. Scan J Caring Sci. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00917.x. Epub August 25, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton MC. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Söderhamn O, Holmgren L. Testing Antonovsky’s sense of coherence (SOC) scale among Swedish physically active older people. Scand J Psychol. 2004;45(3):215–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Medical Association (WMA) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Seoul: 2008. [Accessed May 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Söderhamn O. Self-care activity as a structure: a phenomenological approach. Scan J Occup Ther. 2000;7(4):183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orem DE. Concept Formalization in Nursing: Process and Product. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Company; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beswick AD, Gooberman-Hill R, Smith A, Wylde V, Ebrahim S. Maintaining independence in older people. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2010;20:128–153. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkisian CA, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1837–1843. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SH. Older people’s expectations regarding ageing, health-promoting behaviour and health status. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(1):84–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sartre JP. Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Söderhamn O, Lindencrona C, Ek AC. Ability for self-care among home dwelling elderly people in a health district in Sweden. Int J Nurs Stud. 2000;37(4):361–368. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Söderhamn O, Skisland A, Herrman M. Self-care and anticipated transition into retirement and later life in a Nordic welfare context. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:273–279. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S21385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Söderhamn O. Self-care ability in a group of elderly Swedish people: a phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(4):745–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1998x.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merleau-Ponty M. The Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Söderhamn O. Aspects of validity and reliability in a phenomenological sense. Theoria J Nurs Theory. 2001;10(2):12–16. [Google Scholar]