Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B remains the most common transfusion-transmitted viral infection. We explored the current status of pre-transfusion screening and post-transfusion follow-up testing for hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibodies (anti-HBs) in blood recipients from an area of high HBV endemicity.

Methods

A total of 7,780 blood recipients were transfused with at least 1 unit of blood component at a single university hospital in Korea between January 2006 and December 2009. Their medical records were reviewed, and their demographic and transfusion-related data were analyzed.

Results

Pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs levels were tested in 77.6% (6,037/7,780) of the recipients. The results varied widely according to recipient age. In all, 32.8% (1,982/6,037) of the recipients who were tested had dual negative pre-transfusion results for HBsAg and anti-HBs and, therefore, were at increased risk of HBV transmission. Post-transfusion follow-up testing for HBsAg and/or anti-HBs was performed in 22% (436/1,982) of the increased-risk group.

Conclusions

Our data show that current transfusion-related laboratory testing practice is not sufficient to properly investigate possible post-transfusion infections. Routine laboratory tests, including HBsAg and anti-HBs, should be recommended in transfusion guidelines.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Transmission, Transfusion, Recipients, Test

INTRODUCTION

Transfusion-related safety cannot be overemphasized. To ensure that the blood is safe, a combination of careful donor selection and sensitive screening tests is used. These multiple protective layers have steadily reduced the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and HIV. HBV, however, remains the most frequent cause of transfusion-transmitted viral infection [1].

The risk of HBV transmission depends on the HBV screening strategy used; the selection of low-risk blood donors is the first and most important step [2-4]. The HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) test is the first-line screening test, which, at present, has not been replaced by the HBV nucleic acid test (NAT) in general practice [5, 6]. Korea is a highly endemic area with an HBsAg-positive rate of 4% in the general adult population [7]. According to recent data from 12,461 Korean blood donors, at least 0.016% of released units were viremic but otherwise transfusable [8]. HBV NAT has not yet been implemented in Korea, and the risk of transfusion-transmitted HBV remains high.

In addition to the residual donor-related risk, the immune status of the recipient is another critical factor affecting transfusion transmission of HBV [9]. Recent data suggest that the neutralizing capacity of low anti-HBs may be insufficient and can be overcome by exposure to a high viral load. Immunodeficient elderly patients and patients receiving immunosuppressive treatments may be susceptible to infection with a lower viral dose, even in the presence of anti-HBs [10].

Post-transfusion hepatitis B is not necessarily transfusion-transmitted, and caution should be exercised when concluding that a case of the disease is causally related to transfusion. One critical assessment is pre- and post-transfusion testing of recipients [11, 12], but this is more problematic in areas of high HBV endemicity [13]. In this study, we explored the current status of pre- and post-transfusion testing for HBsAg and anti-HBs in blood recipients from Korea, an area of high HBV endemicity.

METHODS

During the study period, from January 2006 to December 2009, a total of 7,780 blood recipients were transfused with at least 1 unit of blood component at a single university hospital in Seoul, Korea. The study population comprised 3,726 males and 4,054 females, and the median age was 59 yr (range, 0-101 yr). They were divided into 9 age cohorts according to year of birth. The youngest group consisted of recipients who were born between 2000 and 2009, and the oldest group consisted of recipients who were born before 1929.

Using the hospital information system, the demographic and HBV-related laboratory data (HBsAg and anti-HBs levels) of the recipients were retrospectively analyzed. Because there was no clear definition of pre- and post-transfusion laboratory tests in terms of the time period before/after transfusion, pre- and post-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs data were extracted for all patients from the period between July 2005 and June 2010. To be included in the analysis, the pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs tests must have been performed simultaneously. This university hospital is a tertiary care center, and, as of December 2009, had approximately 900 beds and more than 200 medical specialists. The annual blood usage was as follows: 16,170 units in 2006, 34,347 units in 2007, 59,420 units in 2008, and 48,147 units in 2009.

The ADVIA Centaur system (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA) was used for the laboratory measurement of HBsAg and anti-HBs levels by chemiluminescent immunoassay. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. HBsAg results were interpreted as follows: non-reactive (negative), if the index value was less than 1.0; or reactive (positive), if the index value was greater than or equal to 1.0. For samples with an index value of greater than or equal to 1.0 but less than or equal to 50, repeat testing was performed in duplicate. After repeat testing, if 2 of the 3 results were nonreactive, the sample was considered negative for HBsAg; if at least 2 of the 3 results were reactive, the sample was considered repeat reactive for HBsAg. Anti-HBs results were interpreted according to the following criteria: non-reactive (negative), if the result was lower than 7.5 mIU/mL; equivocal, if the result was between 7.5 and 12.5 mIU/mL; or reactive (positive), if the result was higher than 12.5 mIU/mL.

For statistical analysis, MedCalc software (MedCalc version 11.2.1, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions. P values of less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. The distribution of pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs tests

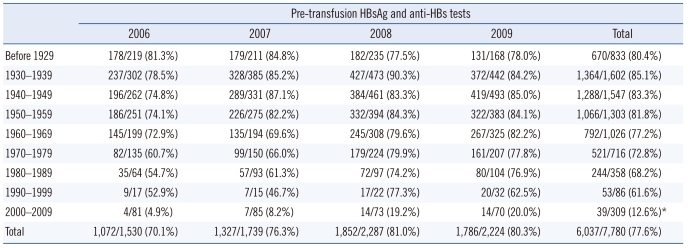

During the 4-yr study period, pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs tests were performed on 77.6% (6,037/7,780) of the blood recipients (Table 1). Among the 9 birth cohorts, the rates of pretransfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs testing varied widely, and ranged from 12.6% to 85.1%. In particular, the rate of testing in the youngest group (2000-2009 birth cohort) was significantly lower than the average rate in the other groups (12.6% vs. 76.3%; P <0.0001), showing a difference of 63.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 59.4-67.3%). The overall rates of pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs testing tended to increase over the 4-yr period, from 70.1% in 2006 to 80.3% in 2009. The birth cohort from 1980-1989 showed the biggest difference (22.2% increase), followed by the 1970-1979 cohort (17.1% increase) and the 2000-2009 cohort (15.1% increase) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs testing in blood recipients according to birth cohort

Data represents the number of tests performed/the number of blood recipients.

*The rate in the youngest birth cohort (2000-2009) was significantly lower than the average rate of the other groups (12.6% vs. 76.3%; P<0.0001), showing a difference of 63.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 59.4-67.3%).

2. Results of pre-transfusion HBsAg/anti-HBs tests

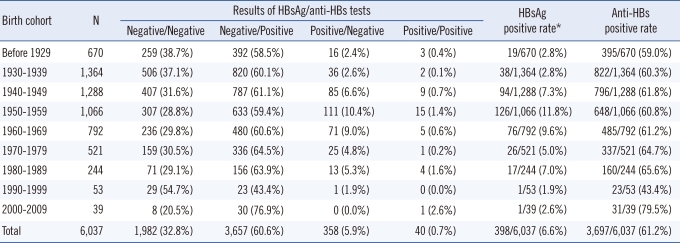

The results of pre-transfusion HBsAg/anti-HBs tests in 6,037 blood recipients were as follows: negative/negative in 32.8%, negative/positive in 60.6%, positive/negative in 5.9%, and positive/positive in 0.7% (Table 2). The overall positive rates of HBsAg and anti-HBs tests were 6.6% (398/6,037) and 61.2% (3, 697/6,037), respectively. When the HBsAg-positive rates of each birth cohort were compared, they were significantly lower in the 2 groups at both extremes of the age cohorts (before 1929, 1930-1939, 1990-1999, and 2000-2009) than in the other 5 groups (1940-1989) (average 2.5% vs. 8.1%; P <0.0001), showing a difference of 5.6% (95% CI, 4.47-6.69%). The highest anti-HBs-positive rate (79.5%) was observed in the birth cohort from 2000-2009, and the lowest (43.4%) in the 1990-1999 cohort. In the other groups, the rate of anti-HBs positivity was approximately 60% (range, 59.0-65.6%). Overall, 32.8% (1,982/6,037) of the recipients showed dual negative results in the HBsAg and anti-HBs tests, and were therefore regarded as being at risk of transfusion-transmitted HBV.

Table 2.

Results of pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs tests in blood recipients according to birth cohort

*The HBsAg positive rate was significantly lower in the 2 birth cohorts at both age extremes (before 1929, 1930-1939, 1990-1999, and 2000-2009) than in the other 5 groups (1940-1989) (average 2.5% vs. 8.1%; P<0.0001), showing a difference of 5.6% (95% CI, 4.47%-6.69%).

3. Post-transfusion follow-up in the risk group

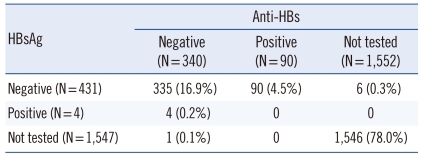

Post-transfusion follow-up HBsAg and/or anti-HBs testing was performed in only 22.0% (436/1,982) of the recipients, who were at increased risk of transfusion-transmitted HBV (Table 3). Neither HBsAg nor anti-HBs levels were tested in the remaining 1,546 recipients. In the 436 recipients with available results, 335 recipients (76.8%) showed HBsAg-negative/anti-HBs-negative status. HBsAg and anti-HBs r esults were positive in 4 (0.9%) and 90 (20.6%) recipients, respectively.

Table 3.

Post-transfusion follow-up in 1,982 recipients with negative results in pre-transfusion HBsAg/anti-HBs tests

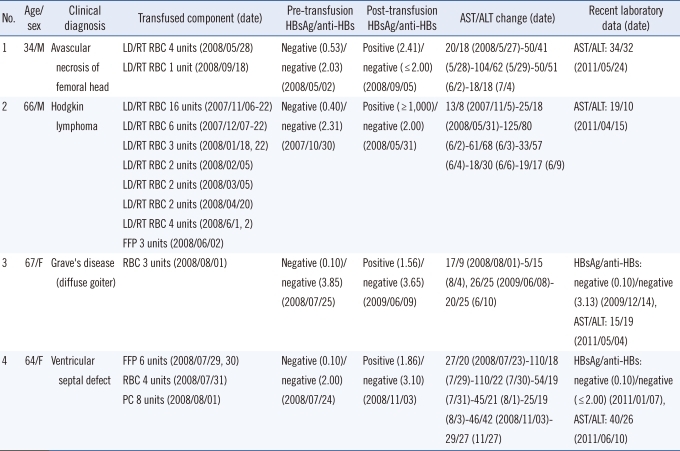

Details of the 4 recipients with HBsAg positive results are summarized in Table 4. These recipients, with the exception of a 66-yr-old male, showed weakly positive HBsAg results. The recent post-transfusion laboratory data showed normal liver enzyme levels in 2 recipients, and the absence of HBsAg and anti-HBs in 2 recipients. HBV DNA data was not available for any of the recipients. The HBsAg results of the donors of all 64 transfused blood units were negative at the time of transfusion. Follow-up HBsAg results were available from repeat donations in 49 out of the 64 donors, and were all negative.

Table 4.

Recipients with positive HBsAg results after transfusion

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; LD/RT RBC, leukocyte-depleted, irradiated RBC; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; PC, platelet concentrate; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase. HBsAg results are presented as index values. The units of anti-HBs and AST/ALT are mIU/mL and U/L, respectively.

DISCUSSION

A systematic approach is required to investigate suspected transfusion-transmitted HBV infections, because post-transfusion hepatitis B is not necessarily transfusion-transmitted. To clarify the causal relationship, other iatrogenic sources of infection should be ruled out, adequate donor follow-up and laboratory testing should be performed, and more importantly, pre- and post-transfusion laboratory data should be available from the recipients [1].

Previous studies have described how the lack of pre-transfusion testing of recipients makes it difficult to establish whether the investigated recipient was infected before or after transfusion [11, 12, 14]. Moreover, immunocompromised recipients could be susceptible to a lower viral dose of HBV even in the presence of anti-HBs and, therefore, may be at higher risk of developing chronic infection or reactivation than immunocompetent recipients [15, 16]. Fluctuation of HBV marker levels over time also makes post-transfusion follow-up of recipients necessary [5, 17]. Altogether, without pre- and post-transfusion test results from the recipient, a thorough investigation into suspected transfusion-transmitted HBV is impossible. This issue is more problematic in highly endemic areas like Korea [7, 8].

In this study, we investigated the current status of pre-transfusion screening and post-transfusion follow-up testing for HBsAg and anti-HBs in blood recipients who were transfused at a university hospital in a highly HBV endemic area. According to our data, pre-transfusion HBsAg and anti-HBs levels were tested in only 77.6% of the recipients (6,037/7,780), and the rates of testing varied widely according to the age of recipients. It is noteworthy that the test rate was remarkably low in the young recipients and tended to increase with increasing age (Table 1). The fact that the lowest rate of testing (12.6%) was in the youngest group might reflect the belief of clinicians that HBV vaccination, which is obligatory in this age group, would be protective against possible HBV infections. However, the pre-transfusion test rates tended to increase during the 4-yr study period, and this finding was more noticeable in the younger age groups. We assume that the clinicians' attitudes toward the screening of infectious markers have changed in favor of screening.

Our data showed that the positive rate of pre-transfusion anti-HBs was approximately 80% in the young recipients (Table 2). Another noticeable finding was that the lowest anti-HBs positive rate (43.4%) was seen in the birth cohort of 1990-1999 (mainly teenagers), demonstrating the necessity of booster vaccination. This indicates that more attention should be paid to the completeness of pre-transfusion testing of recipients.

Post-transfusion follow-up of recipients is another important issue. The recipients with dual negative results for HBsAg and anti-HBs in pre-transfusion tests could be regarded as a potential risk group for HBV transmission. These recipients accounted for approximately one-third of the recipients with available results (32.8%, 1,982/6,037). Post-transfusion follow-up testing of HBsAg and/or anti-HBs was performed in only 22% (436/1,982) of this risk group (Table 3). Among these 436 recipients, 21.5% (94/436) showed changes in HBsAg or anti-HBs status. It is uncertain whether these changes were related to transfusion, because thorough investigations into the possible transfusion transmission of HBV were not performed. For the positive conversion of anti-HBs, the possibilities of HBV vaccination or a transient positive result due to the transfused blood should also be considered. Moreover, 78% of the blood recipients were managed without any post-transfusion follow-up. This implies that the concept of transfusion-related safety did not take root in the clinical practice as firmly as in the blood collection and supply facilities. In our series, we found 4 cases with suspected transfusion-transmitted HBV infections. However, there were no clinical or laboratory data that could confirm the source of infection (Table 4).

In summary, we have explored the current status of pre-transfusion screening and post-transfusion follow-up HBV tests in blood recipients. This study has several limitations. First, the data was obtained from 1 university hospital and may not be representative of the general clinical situation in Korea. Second, because there was no established definition, we arbitrarily designated the period for the pre- and post-transfusion laboratory tests, which extended 6 months before and after the period in which the transfusions were given. Third, the causal relationship between transfusion and changes in HBV laboratory test results was not thoroughly investigated. Nevertheless, our study provides basic data on the current status of HBsAg and anti-HBs testing before and after transfusion in blood recipients. Our data supports the assertion that the current transfusion-related laboratory work-up is not sufficient to properly investigate possible post-transfusion infections. Specifically, HBV vaccination should be performed for candidates of blood transfusion who have negative anti-HBs test results. More emphasis should be placed on the pre-transfusion screening and post-transfusion follow-up of blood recipients. Mandatory laboratory work-up for recipients, including HBsAg and anti-HBs tests, should be suggested in transfusion guidelines.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Candotti D, Allain JP. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2009;51:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber B, Dengler T, Berger A, Doerr HW, Rabenau H. Evaluation of two new automated assays for hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) detection: IMMULITE HBsAg and IMMULITE 2000 HBsAg. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:135–143. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.135-143.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber B. Genetic variability of the S gene of hepatitis B virus: clinical and diagnostic impact. J Clin Virol. 2005;32:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshikawa A, Gotanda Y, Minegishi K, Taira R, Hino S, Tadokoro K, et al. Lengths of hepatitis B viremia and antigenemia in blood donors: preliminary evidence of occult (hepatitis B surface antigen-negative) infection in the acute stage. Transfusion. 2007;47:1162–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhns MC, Kleinman SH, McNamara AL, Rawal B, Glynn S, Busch MP. Lack of correlation between HBsAg and HBV DNA levels in blood donors who test positive for HBsAg and anti-HBc: implications for future HBV screening policy. Transfusion. 2004;44:1332–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vermeulen M, Lelie N, Sykes W, Crookes R, Swanevelder J, Gaggia L, et al. Impact of individual-donation nucleic acid testing on risk of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus transmission by blood transfusion in South Africa. Transfusion. 2009;49:1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song EY, Yun YM, Park MH, Seo DH. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in a general adult population in Korea. Intervirology. 2009;52:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000214633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo DH, Whang DH, Song EY, Kim HS, Park Q. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen and occult hepatitis B virus infections in Korean blood donors. Transfusion. 2011;51:1840–1846. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llewelyn CA, Wells AW, Amin M, Casbard A, Johnson AJ, Ballard S, et al. The EASTR study: a new approach to determine the reasons for transfusion in epidemiological studies. Transfus Med. 2009;19:89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendel S, Levi JE, Biagini S, Candotti D, Allain JP. A probable case of hepatitis B virus transfusion transmission revealed after a 13-month-long window period. Transfusion. 2008;48:1602–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iudicone P, Miceli M, Palange M, Agresti A, Gallo A, Isacchi G, et al. Hepatitis B virus blood screening: impact of nucleic amplification technology testing implementation on identifying hepatitis B surface antigen non-reactive window period and chronic infections. Vox Sang. 2009;96:292–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien SF, Yi QL, Fan W, Scalia V, Kleinman SH, Vambakas EC. Current incidence and estimated residual risk of transfusion-transmitted infections in donations made to Canadian Blood Services. Transfusion. 2007;47:316–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:112–125. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CJ, Lo SC, Kao JH, Tseng PT, Lai MY, Ni YH, et al. Transmission of occult hepatitis B virus by transfusion to adult and pediatric recipients in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2006;44:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roche B, Feray C, Gigou M, Roque-Afonso AM, Arulnaden JL, Delvart V, et al. HBV DNA persistence 10 years after liver transplantation despite successful anti-HBS passive immunoprophylaxis. Hepatology. 2003;38:86–95. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang R. How I treat and monitor viral hepatitis B infection in patients receiving intensive immunosuppressive therapies of undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:3147–3153. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-163493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaba S, Ito A, Miyata Y, Ishii H, Kajimoto S, Tanaka M, et al. Individual nucleic amplification technology does not prevent all hepatitis B virus transmission by blood donation. Transfusion. 2006;46:2028–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]