Abstract

Prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex (PPI) is an operational measure of sensorimotor gating that is deficient in several brain disorders and is disrupted in rats by dopamine agonists. There are robust heritable strain differences between Sprague Dawley (SD) and Long Evans (LE) strains in the sensitivity to the PPI-disruptive effects of dopamine agonists associated with differential gene expression in the nucleus accumbens. Here we compared the contribution of D2 vs. D3 receptors to this heritable difference, using the D3-preferential agonist, pramipexole, the mixed D3/D2 agonist, quinpirole, the mixed D1/D2-like agonist, apomorphine, and the preferential D2 antagonist L741,626. All DA agonists disrupted PPI in SD and LE rats. Greater SD than LE sensitivity for this effect was evident with apomorphine and quinpirole, but not pramipexole. The selective D2 antagonist L741,626 preferentially reversed apomorphine-induced PPI deficits at a dose that did not alter pramipexole-induced PPI deficits. We conclude that the heritable pattern of greater PPI “disruptability” by DA agonists in SD vs. LE rats reflects differences in D2 but not D3 receptor-associated mechanisms.

Keywords: Prepulse inhibition, rat strain, pramipexole, quinpirole, apomorphine, L741626, dopamine, D3 receptor, D2 receptor

Introduction

Evidence suggests that vulnerability for developing schizophrenia can be inherited (Harrison and Weinberger, 2005; Sullivan, 2005) and that genes conferring this vulnerability ultimately do so via changes in brain circuitry. Great effort is being put towards identifying the genetic basis of this vulnerability through the use of endophenotypes, i.e. phenotypes that are intermediate between the genes and the more complex clinical manifestations of these diseases (Gottesman and Gould, 2003; Turetsky et al., 2007). One useful schizophrenia endophenotype may be reduced PPI of the startle reflex (Graham, 1975). Normal prepulse inhibition of startle (PPI) is a cross-species phenomenon that also occurs in humans, rats, and mice when a weak lead stimulus inhibits the response to an intense, abrupt startling stimulus. PPI is reduced in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected first-degree relatives (Braff et al., 1978, 2001; Cadenhead et al., 2000; Kumari et al., 2005) suggesting that deficient PPI may be a useful endophenotype for inherited forms of schizophrenia.

In rats, PPI is potently disrupted by dopamine (DA) receptor agonists, including the mixed D1/D2-like agonist, apomorphine (APO) and the mixed D3/D2 agonist, quinpirole (QUIN; Swerdlow et al., 1986; Mansbach et al., 1988, Peng et al., 1990; c.f. Geyer et al., 2001). Sensitivity to these PPI-disruptive effects of some DA agonists differs across rat strains. For example, Sprague Dawley rats from Harlan Laboratories (SD) are significantly more sensitive to the PPI-disruptive effects of APO, QUIN, and the indirect DA agonist amphetamine (AMPH), compared to Long Evans rats from Harlan Laboratories (LE; Swerdlow et al., 2001b, 2003b, 2004a, b, c; Weber and Swerdlow, 2008). These differences are innate (Swerdlow et al., 2004a, c), neurochemically specific (Swerdlow et al., 2003, 2004b), independent of stimulus modality (Weber and Swerdlow, 2008) and cannot be explained by differences in maternal behavior (Swerdlow et al., 2004a). Finally, these strain differences appear to be linked to inherited properties of DA-linked G-protein function (Swerdlow et al., 2006), and to differential nucleus accumbens gene expression, particularly among genes associated with DA signaling pathways (Shilling et al., 2008). Conceivably, this heritable strain difference in the “disruptability” of PPI by DA activation may provide a useful model for understanding the basis for reduced PPI in heritable, DA-linked brain disorders such as schizophrenia (Braff et al., 1978) and Tourette Syndrome (Castellanos et al., 1996).

While existing data suggest a role of D2-family receptors in this model, we do not know which D2 receptor subtype (D2, D3 or D4) is responsible for the inherited phenotype of PPI “disruptability”. Hence, in the present study, we tested whether SD vs. LE rats differed in sensitivity to the PPI-disruptive effects of the preferential D3 agonist pramipexole, in addition to the mixed D3/D2 agonist QUIN, and the mixed D1/D2-like agonist APO. To parse the potential contribution of D2 receptors to the PPI-disruptive effects of APO and pramipexole, these effects were also tested after pretreatment with the preferential D2 receptor antagonist L741,626 (Millan et al., 2000) in SD rats.

Methods

Subjects

Adult male SD (n = 102) and LE (n = 38) rats (225–250 g; Harlan Laboratories, Livermore, CA) were housed in groups of 2–3 animals per cage, and maintained on a reversed light/dark schedule with water and food freely available. Rats were handled within 2 days of arrival. Testing occurred during the dark phase. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23) and were approved by the UCSD Animal Subjects Committee (protocol #S01221).

Apparatus

Startle chambers for rats (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) were housed in a sound-attenuated room, and consisted of a Plexiglas cylinder 8.2 cm in diameter resting on a 12.5 × 25.5 cm Plexiglas frame within a ventilated enclosure. Noise bursts were presented via a speaker mounted 24 cm above the cylinder. A piezoelectric accelerometer mounted below the Plexiglas frame detected and transduced motion from within the cylinder. Stimulus delivery was controlled by the SR-LAB microcomputer and interface assembly, which also digitized (0–4095), rectified, and recorded stabilimeter readings. One hundred 1-ms readings were collected beginning at stimulus onset. Startle amplitude was defined as the average of the 100 readings.

Startle testing procedure

Approximately 7 days after shipment arrival, rats were exposed to a short “matching” startle session. They were placed in the startle chambers for a 5 min acclimation period with a 70 dB(A) background noise, and then exposed to a total of 17 P-ALONE trails (40 ms – 120 dB(A) noise bursts) that were interspersed with 3 PP12dB+P-ALONE trials (P-ALONE preceded 100 ms (onset-to-onset) by a 20 ms noise burst of 12dB above background). Rats were assigned to drug dose groups based on average %PPI from the matching session, to ensure similar baseline PPI levels between groups. The number of groups created in the matching session equaled the number of dose groups per strain. Average PPI in these groups was 55 % for SD rats and 57 % for LE rats. For each experiment and strain, average %PPI of the dose groups typically differed by less than 3%. Group sizes ranged from 2 to 4 rats/strain/dose group/experimental day. All DA agonist studies (APO, PRA, QUIN) used within-subjects, balanced dose order designs. The number of injections administered to each rat - and the number of experimental days needed to complete the experiment - equaled the number of doses of the DA agonist (including vehicle treatment) tested. The sequence of drug doses administered was counterbalanced between animals to control for any effects of treatment day or sequence. Tests of L741,626 against APO or PRA were two day-studies and had a mixed-model, balanced dose-order design with L741,626 as the between-subjects factor and APO or PRA as the within-subjects factor. Inter-test intervals were 3–5 days for PRA and APO agonist studies, and 6–7 days when PRA and APO were tested against L741,626. Inter-test interval was 11 days for QUIN, to minimize the known long-term effects of QUIN on D2 function and PPI (Culm and Hammer, 2004).

Starting 4 days after the matching session, the effects of PRA were studied in two separate groups of rats. One group of rats received a low dose range (0, 0.03 and 0.06 mg/kg), and another group of rats received a higher dose range (0, 0.1 and 1.0 mg/kg). Each of these PRA experiments was followed by an APO experiment, beginning 4 days after the final injection of the PRA experiment using the same rats. For the APO experiment, rats were treated on two days with either vehicle or 0.5 mg/kg APO. A separate group of rats was tested on two days, with either vehicle or 0.5 mg/kg QUIN. Three experiments with L741,626 were conducted. First, PPI was tested after pretreatment with L741,626 (0, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg) and treatment with APO (0 vs. 0.5 mg/kg). Second, in separate rats, PPI was tested after pretreatment with L741,626 (0 or 1 mg/kg) and treatment with a low dose of APO (0 vs. 0.1 mg/kg). Third, in separate rats, PPI was tested after pretreatment with L741,626 (0, 1, 3 or 10 mg/kg) and treatment with PRA (0 vs. 1.0 mg/kg). Pretreatment time for L741,626 relative to APO or PRA treatment was 30 min.

Immediately (APO), 10 min (QUIN), or 30 min (PRA) after injection of the DA agonists, rats were placed in the startle chambers for a 5 min acclimation period with a 70 dB(A) background noise. They were then exposed to a series of trial types, which were presented in pseudorandom order: (1) P-ALONE ALONE (a 40 ms, 120 dB(A) noise burst); (2–4) P-ALONE preceded 100 ms (onset-to-onset) by a 20 ms noise burst of either 5 (PP5dB+P-ALONE), 10 (PP10dB+P-ALONE), or 15 dB above background (PP15dB+P-ALONE). Interspersed between these trials were trials in which no stimulus was presented, but cage displacement was measured (NOSTIM trials). The session began with 4 consecutive P-ALONE trials and ended with 3 consecutive P-ALONE trials; between these trials were two blocks, each consisting of 8 P-ALONE trials, 5 PP5dB+P-ALONE trials, 5 PP10dB+P-ALONE trials, and 5 PP15dB+P-ALONE trials. Intertrial intervals were variable and averaged 15 s. NOSTIM trials were not included in the calculation of inter-trial intervals. Total session duration was 18.25 min.

Drugs

Apomorphine hydrochloride hemihydrate, quinpirole hydrochloride, 85% (w/v) lactic acid solution, and 1N NaOH solution were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Pramipexole hydrochloride was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, On, Canada), and L741,626 was purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA). Drug doses are based on mg/kg of salts. All drugs were administered subcutaneously (sc) in a volume of 1 ml/kg. Based on pilot studies, PRA (saline, 0.03, 0.06, 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg) was administered 30 min prior to PPI testing, QUIN (saline vehicle or 0.5 mg/kg) was administered 10 min prior to PPI testing, and APO (0.01 % ascorbate/saline vehicle, 0.1 or 0.5 mg/kg) was administered immediately prior to PPI testing. L741,626 (water vehicle, 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg) was dissolved in 0.05–0.5% lactic acid/water (w/v) and pH was adjusted to ≥5 using NaOH. L741,626 was administered 30 min prior to PRA or APO treatment.

Data analysis

PPI was defined as 100−[(startle amplitude on prepulse trials/startle amplitude on P-ALONE trials) × 100], and was analyzed by mixed design ANOVAs. Other ANOVAs were used to assess P-ALONE magnitude, or NOSTIM trials. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Fisher’s PLSD. The magnitude of drug effects on PPI was calculated as “%PPIvehicle-%PPIdrug”. ANCOVAs were used to assess the effect of baseline PPI differences on QUIN-induced PPI effects with strain as a covariate. Regressions were based on simple linear models. Where group differences were detected in P-ALONE magnitude or baseline (vehicle) PPI, several approaches were used to parse these effects from those in PPI-drug sensitivity. Data were collapsed across prepulse intensities. Alpha was 0.05.

Results

APO effects

ANOVA of %PPI revealed significant main effects of strain [F(1,42)=6.16, p<0.02] and

Please convert all stats to house style as above – ed

APO dose (F=198.35, df 1,42, p<0.001), and a significant strain × dose interaction (F=39.72, df 1,42, p<0.001). Separate ANOVAs for each strain revealed significant effects of APO dose in SD rats (F=139.05, df 1,21, p< 0.001) and LE rats (F=59.88, df 1,21, p< 0.001). Importantly, the magnitude of the APO effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIAPO) was significantly larger in SD than LE rats (p<0.001), indicating greater sensitivity to the PPI-disruptive effects of APO in SD than LE rats (Fig. 1A).

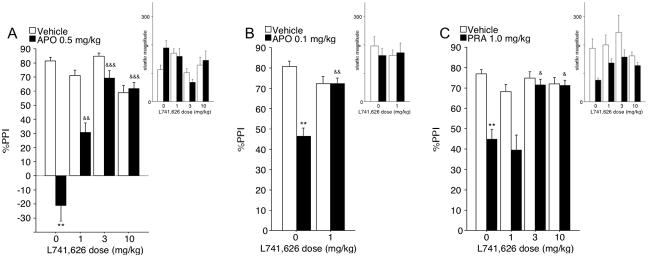

Figure 1. Effects of APO (A) or QUIN (B) on PPI and startle magnitude (insets) in SD and LE rats.

Compared to LE rats, SD rats were significantly more sensitive to the PPI-disruptive effect of APO and QUIN. These effects persisted when basal (vehicle) PPI levels and APO or QUIN effects on startle magnitude were controlled by balancing subgroups or via an analysis of covariance (see text). ** p<0.005, *** p<0.0001.

Based on the significant main effect of strain on PPI, a separate analysis was conducted for subsets of SD and LE rats that were matched for baseline PPI levels. Subsets were constructed by eliminating the extreme responders until baseline PPI was numerically balanced between strains (mean (SEM) of vehicle PPI: SD: 73.0 (1.4), n=12; LE: 72.2 (1.6), n=12). ANOVA of %PPI in these subgroups confirmed the key results: a significant strain × dose interaction (F=14.31, df 1,22, p<0.002), with a significantly greater APO effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIAPO) in SD than LE rats (p<0.002).

ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials revealed significant main effects of strain (F=6.82, df 1,42, p<0.02) and APO dose (F=8.19, df 1,42, p<0.01), and a significant strain × dose interaction (F=14.80 df 1,42, p<0.001). This interaction reflected significant startle-enhancing effects of APO in LE rats (F=17.05, df 1,21, p<0.001), but not in SD rats (F<1). Baseline (vehicle) levels of startle magnitude were almost identical across strains (mean (SEM): SD rats = 170.4 (18.9); LE rats = 176.6 (24.4)) (Fig. 1A, inset).

To assess the impact of the startle-enhancing effects of APO on PPI strain differences, subgroups were matched as above, such that the effects of APO on startle magnitude were numerically balanced between strains (mean (SEM) startle magnitude: SD (n=20) vehicle vs. APO = 161.8 (19.8) vs. 160.7 (30.3); LE (n=8) vehicle vs. APO = 237.0 (50.9) vs. 242.5 (54.1)). ANOVA of P-ALONE amplitude revealed no significant main effect of strain (F=2.70, df 1,26, ns) or APO dose (F<1), and no significant strain × dose interaction (F<1). ANOVA of %PPI in these subgroups again confirmed the key results: a significant strain × dose interaction (F=14.53, df 1,26, p<0.001), with a significantly greater APO effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIAPO) in SD than LE rats (p<0.001).

Inspection of NOSTIM levels revealed very small signal amplitudes (< 1% of pulse alone amplitudes), yet a significant APO × strain interaction (F=10.85, df 1,42, p<0.01), with greater APO responsiveness in SD than LE rats. Simple regression showed that this effect contributed less than 2% of the variance to the observed APO effects on PPI in SD rats, and less than 11% in LE rats (regression weights ns).

QUIN effects

ANOVA of %PPI revealed no significant main effect of strain (F<1), a significant main effect of QUIN dose (F=54.41, df 1,30, p<0.001), and a significant strain × dose interaction (F=6.87, df 1,30, p<0.02). Separate ANOVAs for each strain revealed significant effects of QUIN dose in SD rats (F=33.03, df 1,15, p< 0.001) and LE rats (F=23.24, df 1,15, p< 0.001). Importantly, the magnitude of the QUIN effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIQUIN) was significantly larger in SD than LE rats (p<0.02), indicating greater sensitivity to the PPI-disruptive effects of QUIN in SD than LE rats (Fig. 1B). While the ANOVA detected no main effect of strain on PPI (F<1), an analysis of covariance of the QUIN PPI effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIQUIN) was conducted, with baseline (vehicle) PPI as a covariate and strain as a between factor. This confirmed a significant effect of strain (F=4.87, df 1,28, p<0.05). Thus, SD rats are more sensitive than LE rats to the PPI-disruptive effects of QUIN, even when controlling for any variance linked to levels of baseline PPI.

Because Culm and Hammer (2004) demonstrated lasting effects of QUIN treatment on D2 function and PPI, we examined QUIN effects limited to the initial drug test day. ANOVA confirmed the critical findings: no significant effect of strain (F<1), but a significant strain × QUIN interaction (F=5.38, df 1,28, p<0.05). Because data from this single test day did not permit calculation of a “QUIN PPI effect”, we compared PPI in QUIN-treated SD vs. LE rats; this revealed a significant main effect of strain (p<0.05), confirming that LE rats exhibited higher PPI levels after QUIN (i.e. were less inhibited by QUIN) compared to SD rats.

ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials revealed no significant main effect of strain (F=2.06, df 1,30, ns) or QUIN dose (F=3.06, df 1,30, 0.05<p<0.1), or strain × dose interaction (F=3.18 df 1,30, 0.05<p<0.1). This trend towards an interaction reflected startle-reducing effects of QUIN in SD rats (F=11.34, df 1,15, p<0.005), but not in LE rats (F<1). Baseline (vehicle) levels of startle magnitude were almost identical across strains (mean (SEM): SD rats = 180.3 (18.9); LE rats = 178.2 (36.4)) (Fig. 1B, inset).

To assess the impact of QUIN effects on startle magnitude on PPI strain differences, subgroups were matched as above (mean (SEM) startle magnitude: SD (n=7) vehicle vs. QUIN = 119.4 (15.1) vs. 121.2 (24.4); LE (n=16) vehicle vs. QUIN = 178.2 (36.4) vs. 179.0 (27.0)). ANOVA of P-ALONE amplitude revealed no significant effect of strain (F=2.09, df 1,21, ns) or QUIN dose (F<1), and no significant strain × dose interaction (F<1). ANOVA of %PPI in these subgroups confirmed a significant strain × dose interaction (F=6.34, df 1,21, p<0.05), with a significantly greater QUIN effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIQUIN) in SD than LE rats (p<0.05).

Inspection of NOSTIM levels revealed very small signal amplitudes approximating or less than 1% of pulse alone amplitudes, yet a significant main effect of dose (F=48.76 df 1,30, p<0.0001), but no significant effect of strain (F<1), or strain × dose interaction (F<1). Simple regression showed that this effect contributed less than 7% of the variance to the observed QUIN effects on PPI in SD rats (regression weight ns), and less than 13% in LE rats (regression weight ns).

PRA effects

ANOVA of %PPI for low dose ranges (0.03–0.06 mg/kg) revealed significant main effects of strain (F=53.59, df 1,22, p<0.001) and PRA dose (F=11.33, df 2,22, p<0.001), but no significant strain × dose interaction (F<1). The magnitude of the PRA effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIPRA) in SD and LE rats was not significantly different for either 0.03 mg/kg (F=1.52, df 1,22, ns), or 0.06 mg/kg (F<1). Post-hoc analysis in SD rats revealed a trend towards reduced %PPI for the lowest dose of PRA (0.03 mg/kg; 0.05<p<0.1) and significantly reduced %PPI for 0.06 mg/kg (p<0.002) relative to vehicle. Post-hoc tests in LE rats revealed that %PPI was significantly reduced for 0.03 mg/kg and 0.06 mg/kg doses (both p<0.001) relative to vehicle (Fig. 2A).

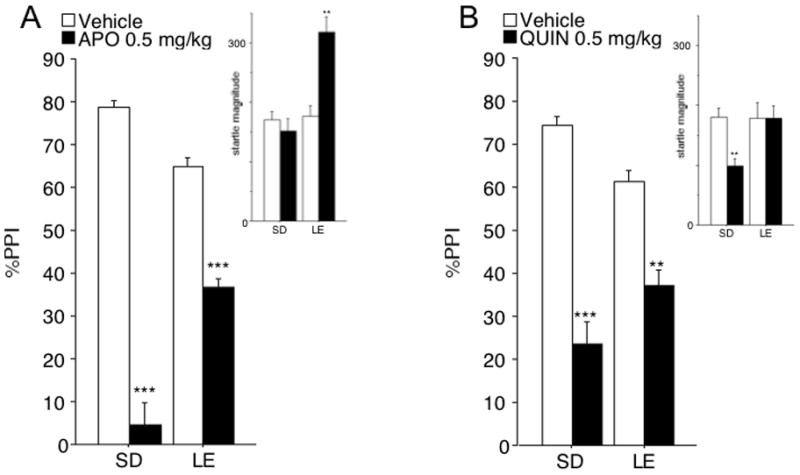

Figure 2. Effects of 0.03 – 0.06 mg/kg (A) or 0.1–1.0 mg/kg (B) PRA on PPI and startle magnitude (insets) in SD and LE rats.

(A) ANOVA of PPI revealed significant effects of strain (SD>LE) and PRA, but no strain × PRA interaction. Thus, unlike APO (Fig. 1A) and QUIN (Fig. 1B), SD vs. LE rats did not differ in the PPI-disruptive effects of PRA. This was also true in subgroups balanced for basal PPI levels and PRA effects on startle magnitude. (B) As with the lower dose range of PRA (Fig. 2A), SD vs. LE rats did not differ in the PPI-disruptive effects of PRA. Again, this was true in subgroups balanced for basal PPI levels. The magnitude of startle suppression in SD rats made it impossible to form subgroups balanced for PRA effects on this measure. However, a simple regression showed that this effect did not contribute a significant proportion of variance to the observed PRA effects on PPI in any of the strains and PRA doses tested (regression weights n.s.). # p<0.1, * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, *** p<0.0001.

Based on the significant main effect of strain on %PPI, a separate analysis was conducted for subsets balanced for levels of baseline PPI (mean (SEM) of vehicle PPI: SD: 70.7 (3.1), n=6; LE: 69.1 (4.6), n=6). These subgroups were also similar with respect to baseline (vehicle) startle magnitude (mean (SEM): SD rats: 137.2 (49.3); LE rats: 133.4 (27.5)). ANOVA of %PPI revealed significant main effects of strain (F=15.46, df 1,10, p<0.005) and PRA dose (F=7.25, df 2,20, p<0.005), and a significant strain × dose interaction (F=5.41, df 2,20, p<0.02). While the overall magnitude of the PRA effect on PPI (%PPIvehicle-%PPIPRA) was not significantly different across strains, sensitivity to the 0.03 dose was greater in LE than SD rats (F=13.39, d 1,10, p<0.005), and a similar trend was detected at 0.06 mg/kg (F=4.34; df 1,10, 0.05<p<0.1).

ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials in rats tested with low doses of PRA revealed a significant main effect of strain (F=7.36, df 1,22, p<0.02), but not dose (F=1.40, df 2,44, ns), and a significant dose × strain interaction (F=4.34, df 2,22, p<0.02). This interaction reflected a trend towards startle-enhancing effects of PRA in LE rats (F=3.10, df 2,22, 0.05<p<0.1), but not in SD rats (F=1.73, df 2,22 ns; Fig. 2A, inset). Post-hoc tests in LE rats revealed that startle magnitude was significantly enhanced by 0.03 mg/kg (p<0.05), but not by 0.06 mg/kg (ns).

The effects of PRA on startle magnitude were balanced across strains, as above, using values for 0.03 mg/kg PRA and vehicle (SD: vehicle = 106.4 (21.1), PRA 0.03 mg/kg=105.6 (15.7), PRA 0.06 mg/kg = 109.5 (25.0), n = 9; LE: vehicle = 197.5 (42.5), PRA 0.03 mg/kg = 225.2 (21.0), PRA 0.06 mg/kg = 231.0 (40.0), n=9). ANOVA of P-ALONE amplitude in these rats revealed a significant effect of strain (F=8.40, df 1,16, p <0.02), but not dose (F<1), and no significant strain × dose interaction (F<1). ANOVA of %PPI in these subgroups confirmed the key results: a significant effect of strain (F=35.79, df 1,16, p<0.0001) and dose (F=7.80, df 1,16, p<0.002), but no significant strain × dose interaction (F=1.18, df 1,16, ns). Importantly, the magnitude of the PRA effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIPRA) was not significantly greater in SD than LE rats for either 0.03 mg/kg or 0.06 mg/kg (both ns).

For the higher PRA dose range (0.1 – 1.0 mg/kg), ANOVA of %PPI revealed a trend towards a strain effect (F=3.00, df 1,22, 0.05<p<0.1), and a significant effect of dose (F=20.80, df 2,44, p<0.0001), but no significant strain × dose interaction (F<1). The magnitude of the PRA effect (%PPIvehicle-%PPIPRA) was not significantly greater in SD than LE rats for either 0.1 mg/kg (F=1.26, df 1,22, ns), or 1.0 mg/kg (F<1) of PRA. Post-hoc analysis in SD rats revealed that %PPI was significantly reduced by 0.1 mg/kg (p<0.005) and 1.0 mg/kg (p< 0.001) PRA relative to vehicle; in LE rats, these effects reached significance only for 1.0 mg/kg PRA (p<0.005) (Fig. 2B).

Based on the strong trend towards strain differences in PPI, subgroups were balanced for vehicle PPI levels across strains (mean (SEM) vehicle PPI: SD (n=6): 69.4 (1.4); LE (n=6): 68.8 (1.9)). The subgroups were also comparable with respect to baseline (vehicle) startle magnitude (mean (SEM): SD: 201.0 (13.2); LE: 199.7 (74.2)). ANOVA of %PPI in these subgroups revealed a significant main effect of PRA dose (F=11.26, df 2,20, p<0.001), but neither an effect of strain (F<1), nor a strain × dose interaction (F<1). The magnitude of the PRA effect on PPI (%PPIvehicle-%PPIPRA) revealed a trend towards greater PPI PRA sensitivity in LE than SD rats at 0.1 mg/kg (F=4.44, df 1,10, 0.05<p<0.1), but not at 1.0 mg/kg (F<1).

ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials revealed a trend towards a strain effect (F=4.07, df 1,22, 0.05<p<0.1), a significant effect for dose (F=4.62, df 2,44, p<0.02), but no strain × dose interaction (F=2.12, df 2,44, ns) (Fig. 2B, inset). The magnitude of PRA-induced startle suppression in SD rats made it impossible to form subgroups balanced for PRA effects on this measure. However, simple regression showed that this effect contributed less than 1% of the variance to the observed PRA effect on PPI for SD vs. LE rats for the highest dose of PRA (1.0 mg/kg; ns). For 0.1 mg/kg of PRA, this effect contributed to less than 8% of the observed PRA effect on PPI (ns) in LE rats, and to less than 20% in SD rats (ns).

NOSTIM levels for both low and high PRA dose range were < 1% of pulse alone amplitudes. For low dose ranges, ANOVA revealed a trend towards a strain effect (F=4.08 df 1,22, p<0.1), but no significant effect of dose (F<1) or dose × strain interaction (F=1.73, df 2,44, ns). For the high dose ranges, ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of strain (F=5.77 df 1,22, p<0.05), but not dose (F=1.84 df 2,44, ns), and or dose × strain interaction (F<1). Simple regression showed that PRA effects on NOSTIM did not contribute a significant proportion of the variance to the observed PRA effect on PPI for any of the rat strains and PRA doses (all regression weights ns). Thus, PRA effects on NOSTIM levels cannot account for the observed PRA effects on PPI.

Effects of L741,626

The D2 receptor antagonist L741,626 was used to assess the contributions of D2 receptor activation to the PPI-disruptive effects of APO and PRA in SD rats.

Studies first tested the effects of pretreatment with L741,626 (0, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg) on the PPI-disruptive effects of 0.5 mg/kg APO. ANOVA revealed significant main effects of APO (F=71.11, df 1,12, p<0.001), and L741,626 (F=10.70, df 3,12, p<0.002), and a significant APO × L741,626 dose interaction (F=24.96, df 3,12, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that APO significantly reduced %PPI in rats treated with 0 mg/kg L741,626 (p<0.005). After APO treatment, PPI was significantly different between groups treated with 0 mg/kg L741,626 and each active dose of L741,626 (vehicle vs. 1 mg/kg (p<0.002); vehicle vs. 3 mg/kg (p<0.001); vehicle vs. 10 mg/kg (p<0.001)) with greater %PPI values in rats treated with L741,626 (Fig. 3A).

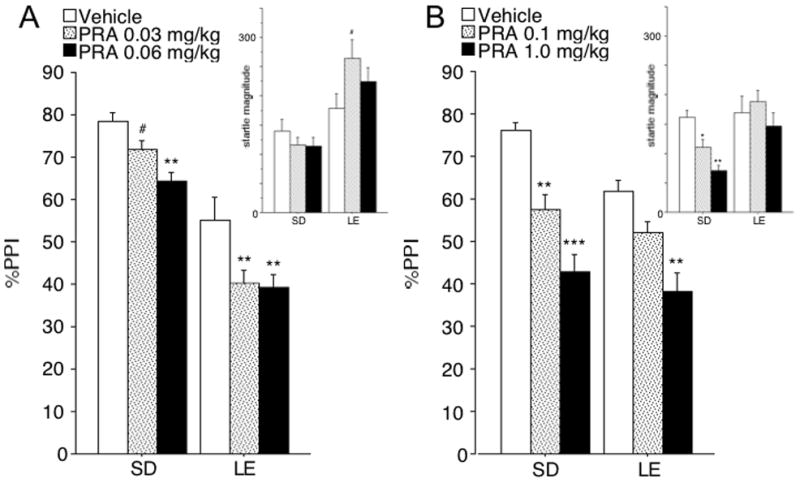

Figure 3. Effects of the D2 receptor antagonist L741,626 on PPI deficits induced by 0.5 mg/kg APO (A), 0.1 mg/kg APO (B), or 1 mg/kg PRA (C) and startle magnitude (insets) in SD rats.

(A) 0, 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg of L741,626 were tested against a standard dose of APO of 0.5 mg/kg. APO significantly reduced %PPI in rats treated with 0 mg/kg of L741,626, and this effect was significantly opposed by each active L741,626 dose. ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials revealed no effect APO, and L741,626, and no APO × L741,626 interaction effect. (B) 0 and 1 mg/kg of L741,626 were tested against a low dose of APO (0.1 mg/kg), selected to match the magnitude of PPI disruption achieved by 1 mg/kg of PRA (see (C)). Again, APO significantly reduced PPI, and this effect was significantly opposed by 1 mg/kg L746,626. ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials revealed no main effect of APO, and L741,626, and no APO × L741,626 interaction. (C) 0, 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg of L741,626 were tested against 1 mg/kg of PRA. PRA significantly disrupted %PPI in rats treated with 0 mg/kg L741,626. This effect was significantly opposed by the 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg doses of L741,626, but not by the 1 mg/kg dose (p>0.6; Fig. 3C). ANOVA of startle magnitude on P-ALONE trials revealed a significant main effect of PRA, reflecting reduced startle magnitude in PRA-treated rats. No effect of L741,626, and no PRA × L741,626 interaction effect were detected. Significance levels derived from post-hoc comparisons between vehicle and DA agonist treatment in rats treated with 0 mg/kg L741,626 are denoted with * symbols. Significance levels derived from comparisons between vehicle and L741,626 pretreatment in rats treated with DA agonists are denoted with & symbols. ** p<0.005; & p<0.05; && p<0.005; &&& p<0.0001.

We next tested the effects of pretreatment with L741,626 (0, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg) on the PPI-disruptive effects of PRA (0 vs. 1 mg/kg). ANOVA of PPI revealed significant main effects of PRA (F=15.50, df 1,28, p<0.001), and L741,626 (F=4.56, df 1,28, p<0.02), and a significant PRA × L741,626 dose interaction (F=3.98, df 3,28, p<0.02). Post-hoc analysis revealed that PRA significantly disrupted PPI in rats treated with 0 mg/kg L741,626 (p<0.005). These effects were significantly opposed by 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg (p<0.02) of L741,626, but not by 1 mg/kg of L741,626 (p>0.6) (Fig. 3C).

Conceivably, the ability of the lowest dose of L741,626 to prevent APO- but not PRA-induced PPI deficits may have reflected greater range produced by the more robust PPI-disruptive effects of this dose of APO. To assess this possibility, we repeated the experiment, using a lower dose of APO (0 vs. 0.1 mg/kg) and the critical doses of L741,626 (0 vs. 1mg/kg). ANOVA of PPI revealed a significant main effect of APO (F=16.42, df 1,14, p<0.002), no significant main effect of L741,626 (F=1.86, df 1,14, ns), but importantly, a significant APO × L741,626 dose interaction (F=16.33, df 1,14, p<0.002). APO significantly reduced %PPI in rats treated with 0 mg/kg of L741,626 (p<0.005), and this effect was significantly opposed by 1 mg/kg L741,626 (p<0.001) (Fig. 3B).

While not described above, in all studies with L741,626 vs. APO or PRA, drug effects on startle magnitude (see Figure 3) and NO STIM levels could not account for the observed patterns of PPI.

Discussion

We previously reported greater sensitivity of SD than LE rats to the PPI-disruptive effects of systemically administered DAergic agonists such as APO, AMPH, or QUIN (Swerdlow et al., 2001b, 2003, 2004a, b, c; Weber and Swerdlow, 2008). The strain differences in PPI-APO and -QUIN sensitivity were confirmed in this study and extended by detailed analyses showing that these strain differences could not be attributed to strain differences with respect to 1) baseline (vehicle) PPI, 2) baseline (vehicle) startle magnitude; 3) drug effects on startle magnitude, or 4) drug effects on NOSTIM levels.

Here we report for the first time the PPI-disruptive effect of the preferential D3 receptor agonist, PRA. The disruption of PPI in rats by PRA confirms earlier reports with other preferential D3 agonists such as ropinirole, 7-OH-DPAT, or PD128,907 (Caine et al., 1995; Swerdlow et al., 1998; Varty and Higgins, 1998; Zhang et al., 2007). With the exception of the Islands of Calleja, the highest levels of D3 receptor densities have been detected in the nucleus accumbens (NAC) in both rodents and humans (c.f. Sokoloff et al., 2006). The disruption of PPI by PRA in two separate rat strains is thus consistent with a prominent role of the NAC in the regulation of PPI (Swerdlow et al., 1986; cf. Swerdlow et al., 2001a).

Importantly, in the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that heritable strain differences in the PPI-disruptive effects of the mixed D1/D2-like agonist, APO, and the mixed D3/D2 agonist, QUIN, do not extend to the preferential D3 agonist PRA. In contrast, sensitivity to the PPI disruptive effects of PRA was comparable between SD and LE rats, and this finding persisted in careful analyses controlling for 1) baseline (vehicle) PPI, 2) baseline (vehicle) startle magnitude; 3) PRA-effects on startle magnitude, or 4) PRA-effects on NOSTIM activity. In instances where trends were detected for strain differences in PRA sensitivity, LE rats tended to be more sensitive to the PPI-disruptive effects of PRA, compared to SD rats.

Conceivably, relatively reduced PPI in LE rats after vehicle treatment might contribute to the blunted impact of APO and QUIN on PPI, via a “floor effect”. However, a floor effect cannot explain the present findings, because in subsets of rats matched for baseline PPI, or following analyses of covariance to control for sources of variance related to baseline PPI, SD rats were still more sensitive to the PPI-disruptive effects of APO and QUIN. Differential APO and QUIN sensitivities of startle magnitude might also conceivably contribute to SD vs. LE difference in PPI APO and QUIN sensitivity, but the present data also do not support such an interpretation because these PPI differences were evident even among “matched” subsets of SD and LE rats that exhibited comparable APO and QUIN effects on startle. Finally, it could be argued that differential APO and QUIN sensitivities on generalized motor activity (NOSTIM levels) may contribute to the observed strain differences with respect to the APO PPI-sensitivity. However, this explanation was also ruled out for both drugs, based on regression analyses.

Since the discovery and cloning of the D3 receptor (Sokoloff et al., 1990), in vivo experiments addressing D3 receptor activation and inhibition have been hampered by several factors. First, commercially available, preferential D3 receptor ligands also have significant affinity for D2 receptors (Luedtke and Mach, 2003; Sokoloff et al., 2006) suggesting that higher doses of these compounds bind to both D3 and D2 receptors. Pramipexole represents one of the more preferential D3 agonists, with an in vitro D3:D2 preference of 7:1 (Piercey et al., 1996, Svensson et al., 1994) relative to the high affinity state of the D2 receptor. Millan and coworkers (2002) have determined the D3:D2 preference of pramipexole to be 90:1 relative to the short isoform of the human receptor (D2S), and 160:1 relative to the long isoform (D2L; Millan et al., 2002). Second, D3 and D2 receptors appear to form domain-swapping heterodimers (c.f. Maggio et al., 2003). Conceivably, this leads to significant challenges of dissecting D3- vs. D2-mediated effects in rats. Despite these challenges, however, recent evidence from in vivo studies in rats suggests that PRA doses of approximately 0.1 mg/kg or less, predominantly lead to D3-receptor associated effects, in the relative absence of D2-receptor associated effects (Collins et al., 2007).

One strategy to approach these challenges is to compare the effects of drugs characterized by a range of DA receptor-subtype affinities. To determine which DA receptor subtypes contribute to the SD vs. LE strain differences in PPI sensitivity, we compared drugs with prominent affinity for D1/D2-like receptors (APO), D3/D2 receptors (QUIN) and D3 receptors (PRA). While none of the drugs are receptor-specific in their binding profiles, the D3:D2 binding ratio for QUIN is approximately 10-fold lower than that for PRA (Piercey et al., 1996). Thus, evidence for SD > LE PPI sensitivity for QUIN but not PRA further argues that this phenotype reflects heritable differences in the sensitivity of D2 but not D3 receptors.

This view was supported by studies in which the effects of APO and PRA were tested against a dose-range of the D2 receptor antagonist L741,626 in SD rats. An alternative strategy would have been to test the effects of APO and PRA against highly preferential D3 receptor antagonists such as SB-277011A and S33084, but such well-characterized D3 antagonists (reviewed in Joyce and Millan, 2005) remain difficult to obtain. L741,626 is among the most selective commercially available D2 receptor antagonists (see Joyce and Millan, 2005, Millan et al., 2000). Nevertheless, its D2:D3 preference ratio is modest and has been estimated as 4:1 for native rat receptors (Cussac et al., 2003). This suggests that at higher doses, L741,626 is likely to lose its preferential D2 inhibition and is likely to inhibit D2 and D3 receptors. In line with this, at the highest doses tested (3–10 mg/kg), L741,626 reversed PPI deficits induced by APO and by PRA. Nevertheless, the lowest dose of L741,626 had no detectable impact on PRA-induced PPI deficits, but significantly opposed the PPI-disruptive effects of both 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg APO. The lower APO dose was selected to disrupt PPI by an amount comparable to that produced by PRA. Thus, under conditions of “matched PPI deficits”, a low dose of L741,626 fully reversed APO-induced PPI deficits, whereas PRA-induced PPI deficits were completely unaffected. These data argue against a major involvement of D2 receptor activation in the induction of PRA-induced PPI deficits, and by extension, suggest that the PPI-disruption induced by PRA is predominantly due to D3 activation. In addition, L741,626 has substantially higher binding ratios for D2 than for D1 (~200), D4 (~80), or D5 (~160) receptors (Millan et al., 2000). While we cannot exclude that cooperation between D2 receptors and these other receptor subtypes may occur, these data indicate that the prevention of APO-induced PPI deficits by the low dose of L741,626 is unlikely due to blockade of D1, D4, or D5 receptors, independent of its antagonism of D2 receptors.

Even though PRA displays preferential binding to D3 receptors relative to all other receptor types, it is not possible to entirely exclude an involvement of a small number of other receptor types in PPI deficits induced by PRA, including the D4 receptor, and perhaps the α2B adrenergic and 5-HT1A serotonergic receptors. First, the in vitro binding ratio of PRA to D3 vs. D4 receptors has been approximated as 12:1 (Millan et al., 2002) or 17:1 (Piercey et al., 1996). This indicates that D4 receptor activation may play some role after treatment with the highest PRA doses tested. Nevertheless, it would be difficult to attribute the lack of SD > LE sensitivity to disruption of PPI by PRA to a major D4 receptor involvement for the lower PRA doses tested. Second, Millan et al. (2002) reported relatively low preferential binding rates in the range of 60:1 for PRA to the D3 receptor relative to the α2B and 5-HT1A receptors. In contrast, Piercey et al. (1996) reported values of > 200:1 for α2 and >1000 for 5-HT1A receptors. Again, if anything, this may indicate an involvement of these receptor types in PPI deficits induced by the highest doses of PRA, but less likely so for the lowest doses of PRA tested. For all other receptors tested, including DA D1 and D5, preferential binding ratios to the D3 receptor have been assessed as 150:1 or greater by both studies (Millan et al., 2002, Piercey et al., 1996). Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that none of these pharmacological tools have absolute receptor specificity, and behavioral responses to these drugs cannot be attributed with certainty to any single receptor or receptor subtype. Perhaps the most conservative conclusion is that, based on the convergent evidence from the present studies, the D2 receptor does not appear to play a prominent role in the PPI-disruptive effects of PRA; by extension, the heritable differences in sensitivity to the PPI-disruptive effects of D2 stimulation are not manifested in a differential sensitivity to PRA.

Our previous studies have determined that the SD vs. LE differences in PPI “disruptability” by DA agonists reflects processes localized within the NAC (Swerdlow et al., 2007), associated with NAC DA-stimulated GTPγS binding (Swerdlow et al., 2006), CREB phosphorylation (Saint Marie et al., 2007), suppression of c-fos expression (Saint Marie et al., 2006) and specific patterns of gene activation (Shilling et al., 2008). The present findings suggest that the heritable behavioral phenotype reflects differential sensitivity of D2 but not D3 receptors. These findings further suggest the testable hypothesis that the D2- and D3-regulation of PPI are mediated via mechanisms that differ at the levels of NAC DA-linked signal transduction and the genes associated with this process.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Maria Bongiovanni in manuscript preparation, and Niveditha Thangaraj and Dave Marzan for their expert technical assistance. Research was supported by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (MW), the Tourette Syndrome Association (MW), the VISN-22 MIRECC (MW), and MH68366 (NRS). NRS has received support from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (research funding) and Allergan Pharmaceuticals (research funding, consultancy funding).

References

- Braff D, Stone C, Callaway E, Geyer M, Glick I, Bali L. Prestimulus effects on human startle reflex in normals and schizophrenics. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:339–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS, Swerdlow NR, Shafer KM, Diaz M, Braff DL. Modulation of the startle response and startle laterality in relatives of schizophrenic patients and in subjects with schizotypal personality disorder: evidence of inhibitory deficits. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1660–1668. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Effects of D3/D2 dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists on prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Fine EJ, Kaysen D, Marsh WL, Rapoport JL, Hallett M. Sensorimotor gating in boys with Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD: preliminary results. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Newman AH, Grundt P, Rice KC, Husbands SM, Chauvignac C, et al. Yawning and hypothermia in rats: effects of dopamine D3 and D2 agonists and antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:159–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culm KE, Hammer RP., Jr Recovery of sensorimotor gating without G protein adaptation after repeated D2-like dopamine receptor agonist treatment in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:487–494. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussac D, Newman-Tancredi A, Sezgin L, Millan MJ. The novel antagonist, S33084, and GR218,231 interact selectively with cloned and native, rat dopamine D(3) receptors as compared with native, rat dopamine D(2) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;394:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Krebs-Thomson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:117–154. doi: 10.1007/s002130100811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman, Gould TD. The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:636–645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK. Presidential Address, 1974. The more or less startling effects of weak prestimulation. Psychophysiology. 1975;12:238–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:40–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. image 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JN, Millan MJ. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as therapeutic agents. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:917–925. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Das M, Zachariah E, Ettinger U, Sharma T. Reduced prepulse inhibition in unaffected siblings of schizophrenia patients. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:588–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke RR, Mach RH. Progress in developing D3 dopamine receptor ligands as potential therapeutic agents for neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:643–671. doi: 10.2174/1381612033391199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio R, Scarselli M, Novi F, Millan MJ, Corsini GU. Potent activation of dopamine D3/D2 heterodimers by the antiparkinsonian agents, S32504, pramipexole and ropinirole. J Neurochem. 2003;87:631–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Dopaminergic stimulation disrupts sensorimotor gating in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;94:507–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00212846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Gobert A, Newman-Tancredi A, Lejeune F, Cussac D, Rivet JM, et al. S33084, a novel, potent, selective, and competitive antagonist at dopamine D(3)-receptors: I. Receptorial, electrophysiological and neurochemical profile compared with GR218,231 and L741,626. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1048–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Maiofiss L, Cussac D, Audinot V, Boutin JA, Newman-Tancredi A. Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:791–804. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RY, Mansbach RS, Braff DL, Geyer MA. A D2 dopamine receptor agonist disrupts sensorimotor gating in rats. Implications for dopaminergic abnormalities in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990;3:211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piercey MF, Hoffmann WE, Smith MW, Hyslop DK. Inhibition of dopamine neuron firing by pramipexole, a dopamine D3 receptor-preferring agonist: comparison to other dopamine receptor agonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;312:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Marie RL, Neary AC, Shoemaker JM, Swerdlow NR. The effects of apomorphine and D-amphetamine on striatal c-Fos expression in Sprague-Dawley and Long Evans rats and their F1 progeny. Brain Res. 2006;1119:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Marie RL, Neary AC, Shoemaker J, Swerdlow NR. Apomorphine effects on CREB phosphorylation in the Nucleus Accumbens of rat strains that differ in PPI sensitivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:37s. [Google Scholar]

- Shilling PD, Saint Marie RL, Shoemaker J, Swerdlow NR. Strain differences in gating-disruptive effects of apomorphine: Relationship to accumbens gene expression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:748–758. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347:146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Diaz J, Le Foll B, Guillin O, Leriche L, Bezard E, Gross C. The dopamine D3 receptor: a therapeutic target for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;5:25–43. doi: 10.2174/187152706784111551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF. The genetics of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K, Carlsson A, Huff RM, Kling-Petersen T, Waters N. Behavioral and neurochemical data suggest functional differences between dopamine D2 and D3 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90718-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Braff DL, Geyer MA, Koop GF. Central dopamine hyperactivity in rats mimics abnormal acoustic startle response in schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21:23–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Taaid N, Oostwegel JL, Randolph E, Geyer MA. Towards a cross-species pharmacology of sensorimotor gating: effects of amantadine, bromocriptine, pergolide and ropinirole on prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:389–396. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Neural circuit regulation of prepulse inhibition of startle in the rat: current knowledge and future challenges. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001a;156:194–215. doi: 10.1007/s002130100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Platten A, Kim YK, Gaudet I, Shoemaker J, Pitcher L, Auerbach P. Sensitivity to the dopaminergic regulation of prepulse inhibition in rats: evidence for genetic, but not environmental determinants. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001b;70:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Stephany N, Wasserman LC, Talledo J, Shoemaker J, Auerbach PP. Amphetamine effects on prepulse inhibition across-species: replication and parametric extension. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:640–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Auerbach PP, Pitcher L, Goins J, Platten A. Heritable differences in the dopaminergic regulation of sensorimotor gating. II. Temporal, pharmacologic and generational analyses of apomorphine effects on prepulse inhibition. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004a;174:452–462. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Crain S, Goins J, Onozuka K, Auerbach PP. Sensitivity to drug effects on prepulse inhibition in inbred and outbred rat strains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004b;77:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Platten A, Pitcher L, Goins J, Auerbach PP. Heritable differences in the dopaminergic regulation of sensorimotor gating. I. Apomorphine effects on startle gating in albino and hooded outbred rat strains and their F1 and N2 progeny. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004c;174:441–451. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Krupin AS, Bongiovanni MJ, Shoemaker JM, Goins JC, Hammer RP., Jr Heritable differences in the dopaminergic regulation of behavior in rats: relationship to D2-like receptor G-protein function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:721–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Bongiovanni MJ, Neary AC, Tochen LS, Saint Marie RL. Strain differences in the disruption of prepulse inhibition of startle after systemic and intra-accumbens amphetamine administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turetsky BI, Calkins ME, Light GA, Olincy A, Radant AD, Swerdlow NR. Neurophysiological endophenotypes of schizophrenia: the viability of selected candidate measures. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:69–94. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varty GB, Higgins GA. Dopamine agonist-induced hypothermia and disruption of prepulse inhibition: evidence for a role of D3 receptors? Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:445–455. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M, Swerdlow NR. Rat strain differences in startle gating-disruptive effects of apomorphine occur with both acoustic and visual prepulses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Ballard ME, Unger LV, Haupt A, Gross G, Decker MW, et al. Effects of antipsychotics and selective D3 antagonists on PPI deficits induced by PD 128907 and apomorphine. Behav Brain Res. 2007;182:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]