Abstract

The relaxivity (contrast-enhancing ability) of EuII-containing cryptates was found to be better than a clinically approved GdIII-based agent at 7 T. These cryptates are among a few examples of paramagnetic substances that show an increase in longitudinal relaxivity, r1, at ultra-high field strength relative to lower field strengths.

Contrast-agent-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a widely used, noninvasive imaging technique for clinical and preclinical research as well as diagnostic medicine. Most clinical imaging is performed at high field strengths (1.5 or 3 T); however, a shift to ultra-high field strength MRI (≥ 7 T) is desirable because of the increased spatial resolution and shorter acquisition times enabled at these fields, which offer the potential to lead to early diagnoses of diseases and more accurate imaging in vivo.1–4 Consequently, preclinical research relies heavily on ultra-high field strengths. A major limitation is that common T1-reducing (positive) contrast agents at lower field strengths, such as GdIII-containing complexes, become inefficient at ultra-high field strengths.2,5 Multiple parameters—including the water-exchange rate, the number of inner-sphere water molecules, the rotational correlation time, and the relaxation times of the electron spins of GdIII—are in a complex interplay that is crucial to increasing relaxivity, r1, which is a measure of contrast-enhancing ability of a contrast agent.2–4 An alternative to GdIII is EuII, which is isoelectronic with GdIII but has a faster water-exchange rate due to its lower charge density. However, until recently, research on EuII chemistry in aqueous solution was limited because of its tendency to oxidize to EuIII.6–8 We have used modified [2.2.2]cryptands to increase the oxidative stability of EuII,6 and here, we report the molecular properties and imaging profiles of a series of EuII-containing [2.2.2]cryptates (1–3 in Fig. 1) that are, to the best of our knowledge, among a few reported contrast agents, and the first lanthanide-based contrast agents, that are more effective at ultra-high field strengths than at lower fields.9

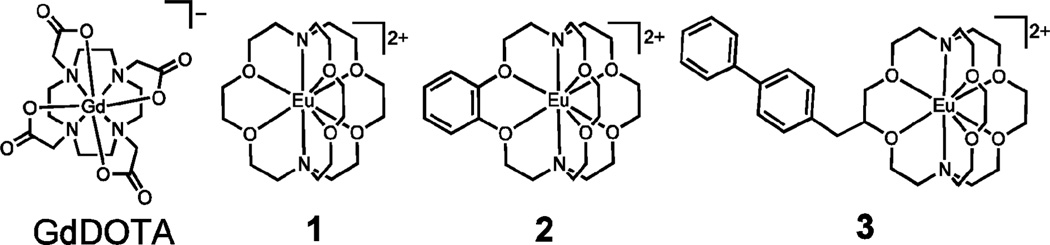

Fig. 1.

Structures of GdDOTA (DOTA = 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N′,N″,N′″-tetraacetate) and EuII-containing cryptates 1–3. Coordinated water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

We hypothesized that EuII-containing [2.2.2]cryptates in aqueous solution could be used as the basis for efficient positive contrast agents for ultra-high field strength MRI because EuII and GdIII are isoelectronic but differ in other molecular parameters that influence relaxivity. This hypothesis is supported by studies of EuII-containing complexes: for example, EuII-containing [2.2.2]cryptate, 1, has been reported to have a fast water-exchange rate.8 The water-exchange rate of 1 is 3 × 108 s−1, which is faster than most GdIII-based complexes and is very close to the optimal value (~108 s−1 at 7 T) for developing efficient MRI contrast agents at ultra-high fields.2,8 Attempts to increase the water-exchange rate of GdIII-containing complexes have been made by altering the coordination number of ligands for GdIII or by increasing steric bulk at the site where inner-sphere water binds.10 However, because of the complicated interplay between water-exchange rate and other parameters that affect relaxivity, there is a need to simultaneously optimize all factors to increase the efficacy of contrast agents. In addition to its optimal water-exchange rate, 1 has two inner-sphere water molecules in a ten-coordinate complex, which should enable higher relaxivity than an equivalent complex with only one inner-sphere water molecule according to Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan (SBM) theory. These favorable molecular properties prompted us to hypothesize that EuII-containing cryptates would be candidates for contrast agents at ultra-high field MRI.

To test our hypothesis, we investigated the imaging (longitudinal relaxivity, r1, at 3 and 7 T) and physical (water-exchange rate, electron-spin relaxation rate, and number of inner-sphere water molecules) properties of a series of EuII-containing [2.2.2]cryptates (Fig. 1). Relaxivity was determined using multiple flip angles in gradient echo imaging experiments performed between 19 and 20 °C at 3 and 7 T (Table 1) and inversion recovery experiments at either 20 or 37 °C at 1.4 and 11.7 T.11 At all of these field strengths, EuII-containing cryptates 2 and 3 displayed higher r1 than clinically approved GdDOTA (up to 46, 71, 92, and 120% higher at 1.4, 3, 7, and 11.7 T, respectively). Furthermore, cryptate 1 displayed a higher relaxivity than GdDOTA at 7 and 11.7 T. We found that the r1 values of GdDOTA were not different at 3 and 7 T (Student t test) but decreased by 29% from 1.4 to 11.7 T. This result was expected based on what is known about fast rotating GdIII-containing complexes.3 However, EuII-containing complexes 1–3 showed an increase in r1 values at 7 relative to 3 T.12 Also, cryptates 1 and 3 displayed an increase in r1 values at 11.7 relative to 1.4 T. The r1 value of cryptate 2 was slightly lower at 11.7 T compared to 1.4 T. Additionally, the r1 values of cryptates 1–3 increased as a function of molecular weight at all field strengths.

Table 1.

r1 values of GdDOTA and EuII-containing cryptates

|

r1 at 1.4 T (mM−1 s−1) T = 37 °C |

r1 at 11.7 T (mM−1 s−1) T = 37 °C |

r1 at 3 T (mM−1 s−1) T = 19.8 °C |

r1 at 7 T (mM−1 s−1) T = 19 °C |

r1 at 11.7 T (mM−1 s−1) T = 20 °C |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GdDOTA | 3.00 ± 0.06 | 2.12 ± 0.02 | 3.69 ± 0.06 | 3.73 ± 0.01 | 2.89 ± 0.004 |

| 1 | 2.09 ± 0.02 | 2.65 ± 0.04 | 3.94 ± 0.12 | 5.01 ± 0.02 | 3.99 ± 0.14 |

| 2 | 3.67 ± 0.09 | 3.34 ± 0.02 | 4.84 ± 0.08 | 6.47 ± 0.14 | 4.81 ± 0.06 |

| 3 | 4.39 ± 0.10 | 4.80 ± 0.06 | 6.31 ± 0.07 | 7.17 ± 0.03 | 6.35 ± 0.01 |

All complexes were in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4). Results are reported as mean ± standard error.

To understand our observations of r1 values, we used variable temperature 17O NMR spectroscopy to determine the molecular parameters expected to influence relaxivity (Table 2): the residence lifetime of bound water molecules, τm298, where water-exchange rate, kex298, is equal to 1/τm298; the longitudinal electronic relaxation time, T1e298; and the number of inner-sphere water molecules, q. To attain the highest relaxivity at ultra-high field strengths, water-exchange rate must be ~108 s−1.2 The water-exchange rates of the EuII complexes are 6–94 times faster than GdDOTA and, consequently, are closer to being optimal at ultra-high field strengths as described by SBM theory. However, our observed water-exchange rate does not limit the relaxation enhancement for fast rotating complexes even at ultra-high fields. As seen from the data in Tables 1 and 2, r1 values were larger for cryptates 2 and 3 relative to 1 despite 2 and 3 having slower water-exchange rates than 1. The relaxivity differences among cyptates 1–3 are likely due to differences in molecular weight because increases in molecular weight correspond to decreases in rotational correlation rates for structurally similar monomeric complexes.13

Table 2.

Relaxivity parameters (based on 17O NMR data) and molecular weights of GdDOTA and cryptates 1–3

| GdDOTA | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| τm298 (ns) | 287 ± 10 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 11.7 ± 0.3 | 48 ± 4 |

| kex298 (108 S−1) | 0.035 | 3.3 | 0.85 | 0.21 |

| q | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| T1e298 (ns) | 29 | 120 | 41 | 1100 |

| ΔH (kJ mol−1) | 70 ± 2 | 60 ± 8 | 34 ± 1 | 49 ± 5 |

| MW (Da) | 591 | 564 | 657 | 731 |

SBM theory also describes the dependence of relaxivity on the electron spin relaxation, which we investigated with 17O NMR studies. Data acquired from variable temperature 17O NMR experiments were refitted using 63 unique values of T1e298 in the range of 10−8–10−3 s, and the T1e298 values that were associated with the best correlation coefficient are reported in Table 2. The electron-spin relaxation rates of the EuII ion in cryptates 1–3 were in the range of 106–107 s−1 and were not limiting as evidenced by the change in relaxivity with molecular weight. Another key parameter in increasing relaxivity at ultra-high fields is the number of inner-sphere water molecules. EuII cryptates have two inner-sphere water molecules, which corresponds to higher efficiency of a contrast agent relative to complexes with fewer inner-sphere water molecules. In general, the superiority of the EuII cryptates over GdDOTA in enhancing relaxivity at ultra-high field strengths is likely due to a combination of factors. We have determined kex298, q, and T1e298 for cryptates 1–3 in an attempt to explain the molecular basis for our observations; however, our results cannot be satisfactorily interpreted using SBM theory.

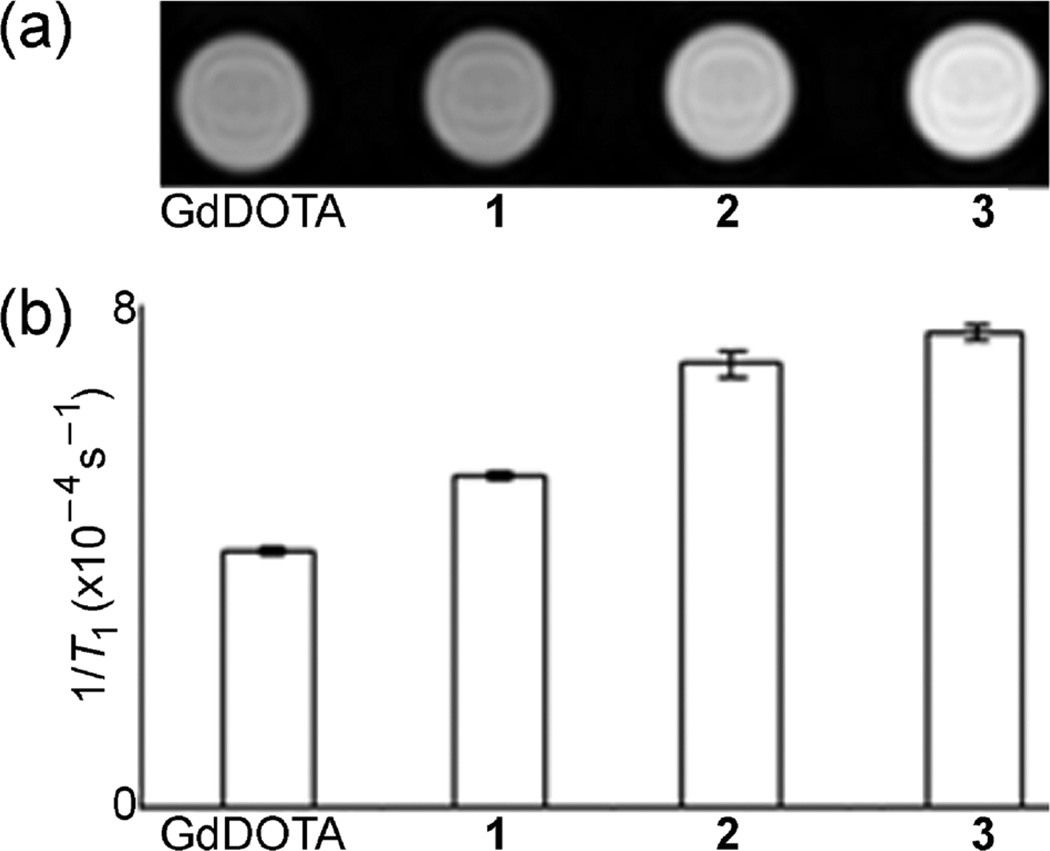

To demonstrate the consequence of having higher relaxivity, we obtained phantom images (images of solutions) of GdDOTA and EuII-containing complexes 1–3 using T1-weighted imaging at 7 T (Fig. 2).The MR images of EuII cryptates 1–3 showed higher signal intensity relative to PBS. This observation is indicative that EuII cryptates are effective at influencing the relaxation of water protons in solution. The signal intensities of the EuII complexes are different from each other (Student t test) with 3 giving rise to the highest signal intensity. The 1/T1 values were between 29 and 89% higher for cryptates 1–3 relative to GdDOTA. An increase in 1/T1 corresponds to higher signal intensity and, therefore, is advantageous for imaging. These imaging experiments demonstrate that cryptates 1–3 are effective contrast agents at ultra-high field strengths.

Fig. 2.

(a) T1-weighted MR images of solutions of GdDOTA (1.0 mM in PBS) and 1–3 (1.0 mM in PBS) at 7 T and 19 °C. The diameter of the tubes that were used for imaging was 6 mm. Imaging parameters were TR = 21 ms; TE = 3.26 ms; and resolution = 0.27 × 0.27 × 2 mm3. (b) Comparison of 1/T1 values of the samples from (a) at 7 T and 19 °C. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

We found that EuII-based complexes 1–3 are effective contrast agents at ultra-high field strengths likely because of the interplay of water-exchange rate, rotational correlation rate, and the presence of two inner-sphere water molecules. To the best of our knowledge, these complexes are among a few reported examples of contrast agents that display increased r1 values at ultra-high field strengths relative to lower fields. Further studies on the physical properties of EuII-containing cryptates are being performed in our laboratory to better understand these results. We expect that our findings will be a step toward addressing the lack of positive contrast agents for ultra-high field strength MRI, and we are currently studying EuII cryptates in more detail to obtain a more complete understanding of the structure–function relationships as well as the thermodynamic and kinetic stabilities of these complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by startup funds from Wayne State University (WSU) and a Pathway to Independence Career Transition Award (R00EB007129) from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health. J. G. was supported by a Thomas C. Rumble Graduate Fellowship from WSU, and M. J. A. gratefully acknowledges a Schaap Faculty Scholar Award. We thank Prabani Dissanayake for acquiring inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry data, Jeremiah Moore for helpful discussions, and Latif Zahid and Yimin Shen for performing imaging experiments.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures and NMR spectra. See DOI: 10.1039/c1cc15219j

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Moser E. World J. Radiol. 2010;2:37. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pitt D, Boster A, Pei W, Wohleb E, Jasne A, Zachariah CR, Rammohan K, Knopp MV, Schmalbrock P. Arch. Neurol. 2010;67:812. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Blow N. Nature. 2009;458:925. doi: 10.1038/458925a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helm L. Future Med. Chem. 2010;2:385. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caravan P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:512. doi: 10.1039/b510982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa J, Ruloff R, Burai L, Helm L, Merbach AE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5147. doi: 10.1021/ja0424169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Livramento JB, Weidensteiner C, Prata MIM, Allegrini PR, Geraldes CFGC, Helm L, Kneuer R, Merbach AE, Santos AC, Schmidt P, Tóth É. Contrast MediaMol. Imaging. 2006;1:30. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Livramento JB, Helm L, Sour A, O’Neil C, Merbach AE, Tóth É. Dalton Trans. 2008:1195. doi: 10.1039/b717390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Moriggi L, Cannizzo C, Prestinari C, Berriére F, Helm L. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:8357. doi: 10.1021/ic800512k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mamedov I, Táborský P, Lubal P, Laurent S, Elst LV, Mayer HA, Logothetis NK, Angelovski G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009:3298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamage N-DH, Mei Y, Garcia J, Allen MJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:8923. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Tóth É, Burai L, Merbach AE. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001:216–217. [Google Scholar]; (b) Caravan P, Tóth É, Rockenbauer A, Merbach AE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:10403. [Google Scholar]; (c) Caravan P, Merbach AE. Chem. Commun. 1997:2147. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burai L, Scopelliti R, Tóth É. Chem. Commun. 2002:2366. doi: 10.1039/b206709a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Kowalewski J, Egorov A, Laaksonen A, Nikkhou Aski S, Parigi G, Westlund P-O. J. Magn. Reson. 2008;195:103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kruk D, Kowalewski J. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:4079. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nilsson T, Parigi G, Kowalewski J. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;18:4476. [Google Scholar]; (d) Svoboda J, Nilsson T, Kowalewski J, Westlund P-O, Larsson PT. J. Magn. Reson., Ser. A. 1996;121:108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Werner EJ, Avedano S, Botta M, Hay BP, Moore EG, Aime S, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1870. doi: 10.1021/ja068026z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Torres S, Martins JA, André JP, Pereira GA, Kiraly R, Brücher E, Helm L, Tóth É, Geraldes CFGC. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007:5489. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pierre VC, Botta M, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:504. doi: 10.1021/ja045263y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Laus S, Ruloff R, Tóth É, Merbach AE. Chem.–Eur. J. 2003;9:3555. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Doble DMJ, Botta M, Wang J, Aime S, Barge A, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10758. doi: 10.1021/ja011085m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cohen SM, Xu J, Radkov E, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:5747. doi: 10.1021/ic000563b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Aime S, Barge A, Borel A, Botta M, Chemerisov S, Merbach AE, Müller U, Pubanz D. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:5104. doi: 10.1021/ic961364o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Physical Principles and Sequence Design. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1999. p. 654. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) The temperatures at 3 and 7 T differed by 0.8 °C. To examine the influence of this temperature variation on relaxivity, we measured cryptate 3 at 11.7 T at temperatures of 19 and 19.8 °C. The relaxivity values were 6.82 ± 0.01 and 6.72 ± 0.01, respectively; Averill DJ, Garcia J, Siriwardena-Mahanama BN, Vithanarachchi SM, Allen MJ. J. Vis. Exp. 2011;53:e2844. doi: 10.3791/2844.

- 13.(a) Floyd WC, III, Klemm PJ, Smiles DE, Kohlgruber AC, Pierre VC, Mynar JL, Fréchet JMJ, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2390. doi: 10.1021/ja110582e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kundu A, Peterlik H, Krssak M, Bytzek AK, Pashkunova-Martic I, Arion VB, Helbich TH, Keppler BK. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011;105:250. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dumas S, Jacques V, Sun W-S, Troughton JS, Welch JT, Chasse JM, Schmitt-Willich H, Caravan P. Invest. Radiol. 2010;45:600. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ee5a9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pierre VC, Botta M, Aime S, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9272. doi: 10.1021/ja061323j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chan KW-Y, Wong W-T. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007;251:2428. [Google Scholar]; (f) Caravan P, Cloutier NJ, Greenfield MT, McDermid SA, Dunham SU, Bulte JWM, Amedio JC, Jr., Looby RJ, Supkowski RM, Horrocks WD, Jr., McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3152. doi: 10.1021/ja017168k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Reichert DE, Hancock RD, Welch MJ. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:7013. doi: 10.1021/ic960495m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Armitage FE, Richardson DE, Li KCP. Bioconjugate Chem. 1990;1:365. doi: 10.1021/bc00006a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.