Abstract

Tumor-associated stromal cells constitute a major hurdle in the antitumor efficacy with oncolytic adenoviruses. To overcome this biological barrier, an in vitro bioselection of a mutagenized AdwtRGD stock in human cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) was performed. Several rounds of harvest at early cytopathic effect (CPE) followed by plaque isolation led us to identify one mutant with large plaque phenotype, enhanced release in CAFs and enhanced cytotoxicity in CAF and several tumor cell lines. Whole genome sequencing and functional mapping identified the truncation of the last 17 amino acids in C-terminal end of the i-leader protein as the mutation responsible for this phenotype. Similar mutations have been previously isolated in two independent bioselection processes in tumor cell lines. Importantly, our results establish the enhanced antitumor activity in vivo of the i-leader C-terminal truncated mutants, especially in a desmotic fibroblast-embedded lung carcinoma model in mice. These results indicate that the i-leader truncation represents a promising trait to improve virotherapy with oncolytic adenoviruses.

Introduction

Virotherapy holds potential as a cancer treatment based on tumor-selective or oncolytic viruses. Oncolytic adenoviruses are at the frontline of virotherapy. Once oncolytic adenoviruses reach the tumor, they replicate, release the progeny, and lyse the infected cell. With this cycle, oncolytic adenoviruses not only eliminate the tumor cell but also amplify the initial inoculum. The released progeny then spreads throughout the tumor and infects neighboring cells repeating the same cycle ideally until the tumor is completely eliminated. Early clinical trials with oncolytic adenoviruses have established the safety of this therapy by multiple routes of administration including the systemic one. However, antitumor responses have been limited.1

After systemic administration, adenovirus is quickly cleared from the bloodstream due to its interaction with complement factors, blood coagulation factors, pre-existing neutralizing antibodies, and platelets, which altogether cause adenovirus degradation and its retention in the liver.2 Once in the tumor, adenovirus face physical barriers imposed by the stroma and the antiviral immune response, that limit their intratumor spread.3

Tumors are heterogeneous masses of malignant cells and stroma. Stroma is composed of extracellular matrix (ECM), fibroblasts, endothelial, and inflammatory cells. Fibroblasts within the tumor stroma are known as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). CAFs present a permanently activated phenotype, induce the formation of an altered ECM responsible for the acceleration of tumor progression, modulate inflammatory response, activate angiogenesis, and stimulate the progression and invasive capacity of tumor cells.4 The tumor-promoting capabilities of CAFs have increased the interest to exploit them as drug targets for anticancer therapy.5 Moreover, fibroblasts can impose limitations for oncolytic adenovirus lateral spread because of their poor replication permissivity and their capacity to produce ECM that might affect the ability of the virus to spread and infect malignant cells.6,7 Because the rate of virus spread within the tumor is critical,8,9 ECM and CAFs are important barriers that should be overcome to increase oncolytic adenovirus' therapeutic index.

Combination of oncolytic adenovirus with drugs such as chemotherapy10,11 or calcium blockers,12 and arming adenovirus with transgenes such as proteolytic enzymes13 or hyaluronidases14 are strategies used to increase their potency and spread through the tumor mass. However, the function of certain transgenes may impair adenovirus replication,15 and its size may also affect adenovirus genome packaging. Alternatively, modification of certain adenoviral proteins, such as deletions in E1B/19K protein16 or overexpression of adenovirus death protein,17 also leads to enhanced cell-to-cell spread and have also been proposed to enhance their therapeutic potential.

Bioselection of randomly mutagenized adenovirus by repeated passaging under defined conditions can also be used to isolate mutants with enhanced potency. This approach identifies point mutations that do not increase adenovirus genome size, and are compatible with viral replication. Additionally, this strategy has the potential to confer novel functions to viral genes.18 Two previous independent bioselection processes in vitro using cancer cell lines identified that the truncation of i-leader C-terminal end increased adenovirus potency in vitro.19,20 Furthermore, we recently identified the E3/19K-445A mutation that increases adenoviral release and antitumor activity in vivo.18

Given the importance of CAFs in promoting tumor progression and also as a barrier to adenovirus spread, we developed an in vitro bioselection process in CAFs to isolate point mutations that enhance adenoviral spread within the tumor. One of the selected mutants displayed an enhanced release without affecting total viral yield in CAFs and large plaque phenotype. By viral genome sequencing and functional mapping we identified the i-leader C-terminal truncation as the mutation responsible for such phenotype. For the first time, we demonstrate that this mutation repeatedly identified in previous screenings in epithelial cells and in the current screening for more potent oncolytic adenovirus in CAF, also represents an advantage in vivo. Our results indicate that the introduction of the i-leader truncation in a conditionally replicative adenovirus holds great promise to improve virotherapy outcome.

Results

Mutagenesis and in vitro bioselection of AdwtRGD mutants with enhanced cytopathic effect in CAFs

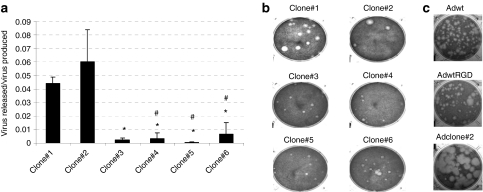

As a basis for our bioselection we chose adenovirus 5 wild type (Adwt) with RGD sequence inserted in the HI loop of the fiber. This modification enhances infectivity in multiple tumor types and fibroblasts,21,22 and it is commonly used by us and other groups in oncolytic adenoviruses. A purified stock of human AdwtRGD was randomly mutagenized with nitrous acid as previously described.23 The mutagenized stock was subjected to multiple rounds of selection in vitro in CAF-1 monolayers, by harvesting the virus when early cytopathic effect (CPE) appeared to enrich the stock with mutants that presented enhanced CPE in these cells. CAF-1 is a nonepithelial CAF primary cell line relatively resistant to adenovirus infection and replication.18 As expected, with each cycle of serial passage in CAF-1 cells, the harvested virus pool progressively demonstrated an improvement in its cytolytic activity, in terms of a shorter time needed for CPE to appear. After six rounds of selection, when the CPE appeared at the same time postinfection as in the previous passage, several clones were isolated by plaque-purification, named Adclone#1–6 and further characterized. To compare the cytopathic properties of the different clones, we characterized their release efficiency (virus released/virus produced ratio) in CAF-1 (Figure 1a), and in A549 cells (data not shown) at 48 hours postinfection (h.p.i); and their plaque size in A549, representative of cell-to-cell spread potency (Figure 1b). Although we also attempted to establish their plaque-size in CAF-1 cells, these cells did not allow plaque formation. We selected Adclone#2 that presented the highest release efficiency in CAF-1 and A549 cells and large plaque phenotype in A549 to continue with the study. Next, we examined the plaque size in A549 to compare the antitumor potency of the selected clone with the parental viruses Adwt and AdwtRGD (Figure 1c). The plaques of the selected mutant appeared earlier and were between two- and fivefold larger in diameter than Adwt and AdwtRGD plaques, which denotes an improved ability of this virus to spread from cell to cell. Note that, there were no differences in the plaque size in A549 cells between Adwt and AdwtRGD. Interestingly, the phenotype of the bioselected mutant was not restricted to CAFs, but it also increased the potency of adenovirus in the lung carcinoma cell line A549.

Figure 1.

Adclone#2 enhances adenovirus' release efficiency and spread compared to AdwtRGD. (a) Viral release efficiency (virus released (TU/ml)/virus produced (TU/ml)) of the different isolated mutants in CAF-1 cells. Viral content of the total (CE) and the extracellular (SN) fractions were analyzed at 48 h.p.i. Mean ratio values (n = 3) ± SD are plotted. *P < 0.05 versus Adclone#1, #P < 0.05 versus Adclone#2. (b) Plaque size of the different clones in A549 cells at day 7 postinfection. (c) Comparative plaque size of adenovirus 5 wild type (Adwt), AdwtRGD and Adclone#2 in A549 at day 7 postinfection. CE, cell extract; h.p.i, hours postinfection; SN, supernatant; TU, transducing units.

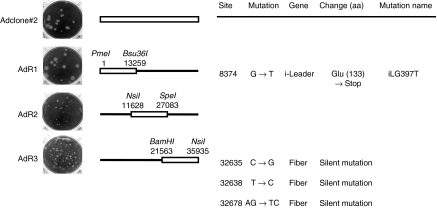

Identification of the mutation responsible for the increased CPE: iLG397T

To identify the mutation responsible for the enhanced cytolytic activity, we carried out the complete sequence analysis of Adclone#2 genome and the functional mapping of its phenotype, by generating recombinants between Adclone#2 and Adwt genomes. The analysis of the complete genome revealed the presence of four mutations. Three of them were silent mutations located through the fiber protein coding region, whereas the fourth was a G to T point mutation in position 8,374 of the adenovirus genome corresponding to nucleotide 397 of the i-leader sequence. The Adclone#2/Adwt recombinant mutants (AdR1, AdR2 and AdR3 represented schematically in Figure 2) mapped the mutation responsible for the large plaque phenotype at position 1–13,259 of Adclone#2 genome (Figure 2). Therefore, the 8,374 mutation (iLG397T) was identified as responsible for the large plaque phenotype of Adclone#2. This mutation caused the introduction of a stop codon in amino acid 133 of the i-leader protein leading to the truncation of the last 17 amino acids in the C-terminal tail of the protein. Adclone#2 was renamed AdiLG397T-RGD and used for further characterization. AdR1 (containing the i-leader truncation mutation and wild-type fiber) was renamed AdiLG397T, and used from this moment on when compared with non-RGD-fiber modified virus. The large plaque phenotype of this mutation in epithelial cells had been described before19,20 but the mechanisms and its in vivo activity remained unexplored.

Figure 2.

Identification of the mutation responsible for Adclone#2 phenotype. Left, plaque size in A549 cells at day 7 postinfection of the parental virus Adclone#2 and the recombinant mutants AdR1, AdR2, and AdR3. Middle, schematic representation of Adclone#2, AdR1, AdR2, and AdR3 genomes, where black line represents adenovirus 5 wild type (Adwt) genome and white bar represents Adclone#2 genome. The enzymes used for the construction of the recombinants are indicated. Right, mutations present in the genome of Adclone#2. Site and gene mutated are indicated. Nucleotide and amino acid (aa) changes (→) are indicated. Amino acid position affected by the mutation is indicated in parentheses.

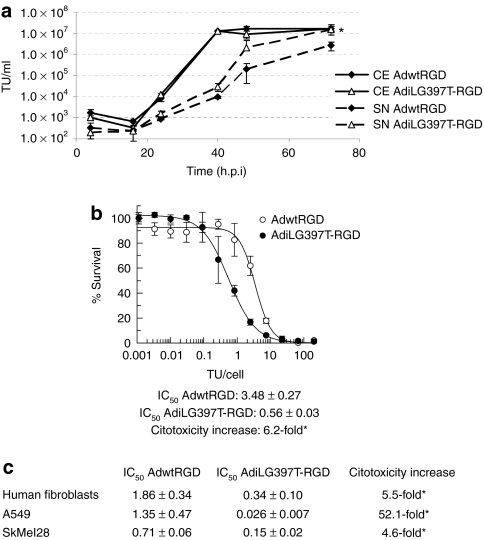

iLG397T mutation enhances adenoviral release and cytotoxicity of adenovirus wild type in vitro

In order to distinguish whether the large plaque phenotype exhibited by AdiLG397T-RGD was caused by an increase in the total virus yield or an enhanced adenovirus release, we synchronically infected CAF-1 monolayers with AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD. At the indicated time-points, we collected samples from the supernatant (SN) and the complete cell extract (CE) and quantified the amount of virus present in these samples. The measure of extracellular (SN) and total virus produced (CE) in CAF-1 cells showed that AdiLG397T-RGD was released more efficiently from infected cells compared to AdwtRGD [10-fold at 48 h.p.i and 5.6-fold at 72 h.p.i (P = 0.0016) increase of the virus in the SN, whereas the total virus yield remained unaffected (Figure 3a)]. This is also the case of other mutants with reportedly increased lytic activity in tumor cells such as AdE3/19K-445A18 or AdE1B/19Kdel mutant which present an efficiency release (ratio between the virus released present in the SN and the total virus produced present in the CE) 18-fold higher than the virus control, as our mutant AdiLG397T-RGD that presents a release efficiency 19-fold higher than the virus control in CAF-1 cells at 48 h.p.i.

Figure 3.

iLG397T mutation increases adenoviral release and cytotoxicity of AdwtRGD. (a) Kinetics of viral production and release of AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD in CAF-1 cells. Extracellular (SN) and total virus produced (CE) was measured at the indicated time points. Mean values (n = 3) ± SD are plotted. *P < 0.002. (b) Comparative dose–response curve of AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD in CAF-1 cells. The IC50 (TU/cell needed to reduce cell viability to a 50%, n = 3) ± SE of both viruses and the cytotoxicity increase are shown. *Statistical significance between AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD (P < 0.05). (c) Comparative cytotoxicity of AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD in different cell lines. IC50 values (n = 3) ± SE of both viruses and the AdiLG397T-RGD cytotoxicity increase are shown. *P ≤0.05 between AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD. Adwt, adenovirus 5 wild type.

The enhanced efficacy of release of AdiLG397T-RGD mutant led to an enhanced cytotoxic activity in CAF-1, the cell line where the bioselection was performed, decreasing its IC50 value 6.2-fold compared to AdwtRGD (P = 0.0056) (Figure 3b). However, this phenotype was not restricted to this cell line as the iLG397T mutation also increased the cytotoxicity with respect to AdwtRGD in normal human fibroblasts (5.5-fold reduction in IC50 value, P = 0.05), and in tumor cell lines such as A549 (52.1-fold reduction in IC50 value, P = 0.003), and SkMel-28 (4.6-fold reduction in IC50 value, P = 0.0015) (Figure 3c).

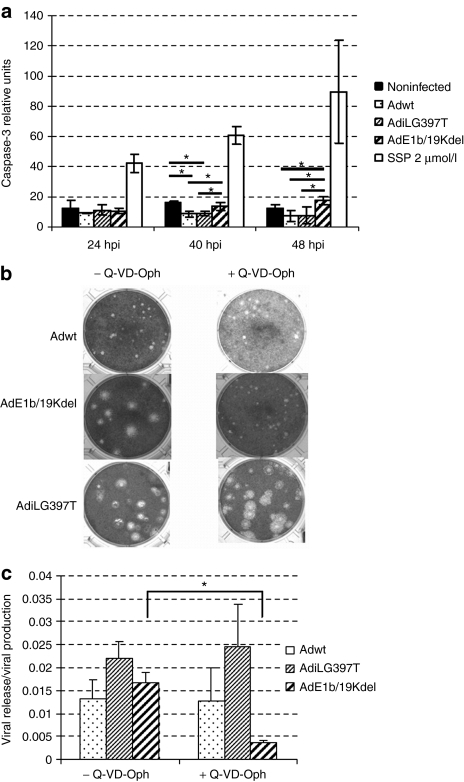

AdiLG397T-RGD phenotype is independent of apoptosis

Deletion of genes which inhibit apoptosis during the early stage of adenovirus replication, such as E1B/19K, also results in a large plaque phenotype.24 To determine the induction of apoptosis during i-leader mutant-virus replication we studied caspase-3 activation throughout the viral cycle (Figure 4a). AdE1B/19Kdel and staurosporine (apoptosis inductor) were used as positive controls for apoptosis induction in this analysis. Our results indicate that AdiLG397T, as well as Adwt, did not activate apoptosis, whereas AdE1B/19Kdel infected cells present higher levels of caspase-3 activation at 40 and 48 h.p.i confirming apoptosis activation during the infection with this virus. To further confirm that apoptosis was not playing a role on AdiLG397T-enhanced release, we studied the mutant's plaque size and release efficiency (virus released/total virus produced) in the presence of Q-VD-OPh, a broad spectrum caspase inhibitor. As Figure 4b and c show, although apoptosis was effectively inhibited (the E1B/19K-deleted virus treated with Q-VD-OPh lost its large plaque phenotype and release efficiency), AdiLG397T release and plaque size was not affected in the presence of the inhibitor, indicating that iLG397T phenotype is independent of apoptosis.

Figure 4.

i-leader truncation phenotype is apoptosis-independent. (a) Caspase-3 activation in noninfected, adenovirus 5 wild type (Adwt), AdiLG397T, and AdE1B/19Kdel infected cells and SSP treated cells at indicated time points. Noninfected cells show the basal level of apoptosis. SSP, staurosporine. *P < 0.05. (b) Plaque size in A549 cells in the presence of Q-VD-0Ph 10 µmol/l (final concentration) at day 7 postinfection. (c) Viral release efficiency (virus released, SN/virus produced, CE) with or without 20 µmol/l Q-VD-0Ph in A549 cells. Viral content of the total (CE) and the extracellular (SN) fractions were analyzed at 40 h.p.i. Mean ratio values (n = 3) ± SD are plotted. *P < 0.05.

iLG397T is a gain of function mutation but its combination with E3/19K-445A mutation has no additive effect on adenovirus release

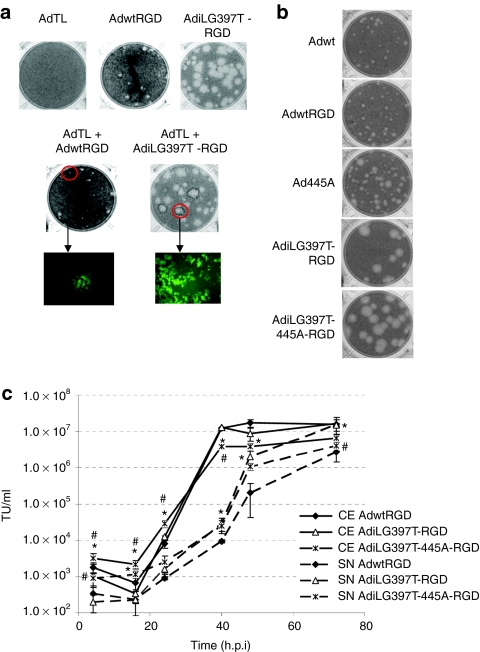

To determine whether the phenotype of AdiLG397T-RGD was due to a dominant function conferred by the truncated i-leader protein or due to a general function defect of the protein, we performed a plaque-forming assay initiated from a coinfected cell (cell plaque-assay). To this end, we coinfected A549 cells with AdiLG397T-RGD and AdTL, a GFP-expressing E1 deleted adenoviral vector unable to replicate in A549 cells. Serial dilutions of these coinfected cells were added to A549 monolayers and covered with agarose to avoid virus diffusion. Seven days later, the plaque-size and the fluorescence of the plaques were analyzed. Green-fluorescent plaques (Figure 5a) were produced by coinfected cells where both wild type (from AdTL) and mutated i-leader coexisted, because AdTL requires the E1 region of the replicative virus to spread; its large plaque phenotype indicated that the i-leader truncation is a gain of function mutation, as a loss of function would have been rescued by the presence of wild-type i-leader.

Figure 5.

i-leader truncation is a dominant mutation, but its combination with E3/19K-445A mutation does not increase adenovirus spread and release compared with i-leader truncation alone. (a) Cell plaque-assay of AdTL, AdwtRGD, AdiLG397T-RGD, and AdTL + AdwtRGD and AdTL + AdiLG397T-RGD coinfected cells. At day 7 postinfection, fluorescence of the plaques was analyzed and representative pictures were taken, then the cell plaque-assays were stained. (b) Plaque size in A549 of Adwt, AdwtRGD, Ad445A, AdiLG397T-RGD, and AdiLG397T-445A-RGD seven days postinfection. (c) Kinetics of viral production and release in CAF-1 cells of AdwtRGD, AdiLG397T-RGD, and AdiLG397T-445A-RGD. Mean values (n = 3) ± SD are plotted. *P < 0.05 versus AdwtRGD, #P < 0.05 versus AdiLG397T-RGD.

We have previously described that the E3/19K-445A dominant mutation also increases adenovirus release without affecting total virus progeny yield.18 Given the dominance and the phenotype of both mutations, we hypothesized that adenovirus antitumor potency could be increased even more by combining both mutations. To this end, we constructed AdiLG397T-445A-RGD and characterized its plaque size in A549 and its kinetics of viral production and release in CAF-1 cells. As shown in Figure 5, the combination of AdiLG397T-RGD with E3/19K-445A mutation did not enhance either the plaque size (Figure 5b) or the release from the infected cell (Figure 5c) of AdiLG397T-RGD. Moreover, the total production yield of AdiLG397T-RGD-445A is reduced compared to AdiLG397T-RGD, with statistical significance from 4 to 40 h.p.i. We concluded that the E3/19K-445A mutation did not increase the oncolytic potency of AdiLG397T-RGD.

iLG397T mutation enhances AdwtRGD antitumor efficacy in vivo without affecting its toxicity profile

Once the improved cytotoxicity of AdiLG397T-RGD in vitro in CAFs and tumor cell lines was demonstrated, we sought to determine whether it conferred an advantage in vivo. First, we performed a preliminary toxicity study in immunocompetent BalbC mice comparing AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD intravenous administration at 2.5 × 1010 viral particles (vp) and 5 × 1010 vp. No differences were observed in the body weight variation between AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD (Supplementary Figure S1a and Supplementary Materials and Methods) moreover there were no differences either in the transaminases elevation after both viruses administration at the higher dose (Supplementary Figure S1b and Supplementary Materials and Methods) or in the platelets count and lymphopenia (Supplementary Figure S1c and Supplementary Materials and Methods). After confirming that i-leader truncation does not affect the toxicity profile, we studied the antitumor efficacy of AdiLG397T-RGD compared to AdwtRGD in vivo. Mice-bearing subcutaneous A549 lung carcinoma xenograft tumors were treated with a single systemic dose of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), AdwtRGD or AdiLG397T-RGD at 2.3 × 1010 vp/mice. As Figure 6a displays, the enhanced release of AdiLG397T correlated with an increase in the oncolytic efficacy of this virus and resulted in a 2.7-fold reduction in the tumor volume of AdiLG397T-RGD-treated mice compared to the AdwtRGD group at the end of the experiment (day 70), although these values were only significant from day 38 to 56 after virus administration. This antitumor efficacy improved the mean survival time from 35.5 days for AdwtRGD to 55.58 days for the AdiLG397T-RGD-treated mice (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

i-leader truncation enhances antitumor efficacy of AdwtRGD in a lung carcinoma tumor model. (a) Nude mice-bearing lung carcinoma (A549) xenograft subcutaneous tumors were treated with a single intravenous dose of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), AdwtRGD or AdiLG397T-RGD at 2.3 × 1010 viral particles (vp) per mouse. Mean tumor volume values (n = 8–10) ± SEM are potted. *P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test compared to AdwtRGD. (b) Kaplan–Meier survival curves after administration of a single intravenous dose of PBS, AdwtRGD or AdiLG397T-RGD. Adwt, adenovirus 5 wild type.

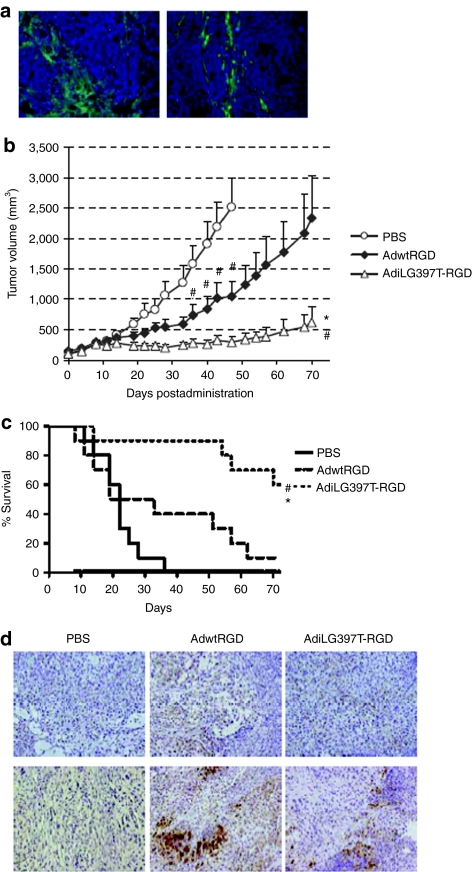

Since the enhanced-release phenotype of AdiLG397T-RGD was especially relevant in CAFs, we assessed its in vivo activity in a tumor model that included tumor cells and human fibroblasts. It has been previously described that human fibroblasts were not able to long-term survive in xenograft tumors because cancer cells recruit new stroma of murine origin.25 Despite this, we implanted subcutaneous tumors with different proportions of human fibroblasts and A549 cells (5 × 106 A549 cells + 106 human fibroblasts or 106 A549 cells + 3 × 106 human fibroblasts) to ensure the presence of these human fibroblasts. Specific immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections 32 days after implantation revealed the presence of human fibroblasts in both types of tumors (Figure 7a). Given the persistence of human fibroblasts in this tumor model, an in vivo efficacy experiment was performed in mice-bearing subcutaneous tumors containing a mix of both A549 and human fibroblasts. Mice were treated as previously with a single systemic dose of PBS, AdwtRGD, or AdiLG397T-RGD at 2.3 × 1010 vp/mice. The antitumor activity of AdiLG397T-RGD in this model was highly superior to AdwtRGD, presenting statistical significance from day 22 until the end of the experiment (day 70) and giving a sixfold reduction of the tumor volume compared to AdwtRGD at the end of the treatment (Figure 7b). Such enhancement in antitumor efficacy translated into a highly significant increase in the mean survival time from 21.8 days in the PBS group to 34.6 days in the AdwtRGD group and 62.7 days in the AdiLG397T-RGD group (P = 0.007 compared to AdwtRGD and P = 0.0005 compared to PBS) (Figure 7c). Moreover the tumor weight at the end of the experiment showed a fourfold reduction from 1 g in AdwtRGD-treated mice to 0.25 g in AdiLG397T-RGD group (P = 0.028 compared with AdwtRGD). The presence of human fibroblasts at day 19 postinjection (Figure 7d) and adenovirus in the tumors at the same time point (Figure 7d) was determined by specific immunostaining against human vimentin and adenovirus E1A protein, respectively, confirming that the antitumor effect was due to adenovirus replication. Virus presence was further confirmed at the end of the experiment (data not shown).

Figure 7.

i-leader truncation enhances antitumor efficacy and animal survival in a desmotic lung carcinoma (A549/human fibroblast) tumor xenograft. (a) Antihuman fibroblast antigen immunofluorescence staining of OCT-embedded tumors from the established lung carcinoma/ human fibroblasts tumors. Left, 5 × 106 A549 cells + 1 × 106 human fibroblasts tumors. Right, 1 × 106 A549 cells + 3 × 106 human fibroblasts tumors. (b) Nude mice-bearing A549/human fibroblasts xenograft subcutaneous tumors were treated with a single intravenous dose of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), AdwtRGD or AdiLG397T-RGD at 2.3 × 1010 vp/mouse. Mean tumor volume values (n = 10) ± SEM are plotted. *P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test compared to AdwtRGD. #P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test compared to PBS group. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves after administration of a single intravenous dose of PBS, AdwtRGD or AdiLG397T-RGD. *P < 0.01 by log-rank test compared to mice injected with AdwtRGD. #P < 0.001 by log-rank test compared to mice injected with PBS. (d) Human fibroblasts (top) and adenovirus (bottom) immunochemical staining of paraffin-embedded tumors at day 19 postinjection, by specifically detecting human vimentin and E1A, respectively. Adwt, adenovirus 5 wild type.

Discussion

Clinical trials with oncolytic adenovirus to date have demonstrated a good toxicological and safety profile; however the reduced efficacy observed highlights the need to improve the potency of these antitumor agents. One of the main obstacles to virotherapy is the limited spread of the virus throughout the tumor mass. Since CAFs are resistant to adenovirus infection and replicative cycle, they exert a physical barrier; moreover CAFs secrete ECM components which can also pose limitations to virus dispersion. Bioselection of human adenovirus random mutants has been postulated as a powerful method to develop more potent oncolytic adenoviruses.18,19,20 We hypothesized that the repeated passage of AdwtRGD random mutants in CAF monolayers would exert a selective pressure that would favour the replication of mutants with an increased potency in these cells. Consequently the isolated viruses should spread throughout the tumor mass more efficiently leading to a higher antitumor efficacy in vivo.8,9

By using this approach, we have isolated a mutant that presented large plaque phenotype and enhanced cytotoxicity as a consequence of early release of the virus from the infected cell without affecting total viral progeny. A double strategy including whole genome sequencing and functional mapping allowed us to identify iLG397T as the mutation responsible for the phenotype. This mutation introduced a stop codon and caused truncation of the i-leader protein C-terminal domain. Previous bioselection processes in tumor cell lines have identified similar C-terminal i-leader truncated mutants that presented the same increased cytotoxicity and large plaque phenotype emphasizing the importance of this mutation for adenovirus release.19,20 Consistent with these results, the phenotype of the mutant we isolated is not restricted to CAFs (where the bioselection process was done) but it also increases virus-induced cytotoxicity in tumor cell lines. Interestingly, the convergence between different bioselection processes using tumor cells and CAFs together with our in vivo data confirms the native release kinetics of the viral progeny is a major limitation for adenovirus in both environments, and points out that is one of the steps to be improved in order to increase the oncolytic therapy efficiency.26

Yan et al. described that truncation of the i-leader led to an acceleration of DNA synthesis, protein expression, and viral replication.19 However further work from Subramanian et al. demonstrated that the i-leader truncation did not affect either DNA or protein synthesis, and instead hypothesized that virus release was accelerated.20 Both groups already noted that this phenotype was apoptosis-independent. In line with Subramanian et al., we confirmed that the i-leader truncation enhances adenovirus release by analyzing the extracellular and the total virus produced at different time points in a one-round replication experiment. We also determined that the viral protein expression profile was not affected (data not shown), and also the apoptosis-independency of the phenotype. Our data demonstrates that the presence of iLG397T mutation in adenovirus genome does not impact significantly on hepatic and hematologic toxicity. Moreover, we show an enhanced antitumor efficacy of AdiLG397T-RGD compared to AdwtRGD in two different tumor xenograft models. The antitumor efficacy of AdiLG397T-RGD is especially relevant in the mixed lung carcinoma cells and human fibroblasts model. Because human tumors are highly desmotic,27 this model represents better the situation that virus will face once inside a human tumor where fibroblasts limit virus dissemination and promote tumor growth. However, it remains to be shown whether improved lytic activity of AdiLG397T-RGD in fibroblasts, in addition to its enhanced performance in tumor cells, is necessary for the superior therapeutic activity in vivo. To prove this we attempted to colocalize virus and human fibroblasts in tumors by staining with anti-vimentin and anti-E1a. We could not obtain a positive result probably due to the low proportion of human fibroblasts and the limited foci of virus replication.

The mechanism affected by the C-terminal truncation of i-leader is unclear. The i-leader sequence is present in some late mRNAs (mainly in the L1-52/55K mRNAs) and it also codes for a protein of unknown function. In cis, synthesis of the i-leader protein leads to destabilization of i-leader-containing mRNAs undergoing translation, which reduces to half L1-52/55K protein levels in trans.28 It has also been hypothesized that the i-leader protein may play a role in the initiation of viral DNA replication or in the switch from early-to-late expression profile.29 Coinfection studies where the i-leader protein was provided in trans, showed the i-leader truncation is a dominant mutation that represents a gain of function of the truncated protein. The phenotype of the i-leader null mutant, which did not significantly change the plaque size of Adwt, support this hypothesis.20 It has also been described that the truncated protein accumulates more rapidly in the infected cells than the wild-type protein without altering its subcellular localization.19 In our effort to elucidate the mechanism of i-leader truncation we have performed expression arrays (Affimetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0ST) comparing the gene expression profile of Adwt versus AdE3/19K-445A and AdiLG397T, both having the same viral release kinetics. From functional clustering analysis we hypothesized that the enhancement of adenovirus release by the i-leader truncation could be related to activation of apoptosis, activation of nuclear factor-κB and cytokine expression, or alteration in mRNA processing machinery. Apoptosis inhibitors allowed us to discard this pathway, but further research is needed to explore the contribution of nuclear factor-κB or mRNA processing.

Adenovirus death protein promotes adenovirus release.30 However, this process is rather inefficient, and only 20% of adenovirus produced is released at 48 h.p.i. Such observation has led to the idea that the native rate of adenovirus release hinders the intratumor spread of oncolytic adenovirus.26 Several strategies have been developed to increase oncolytic adenovirus potency by improving adenoviral release, including adenovirus death protein overexpression,17,31 apoptosis induction,32,33 and bioselection of mutations.18,19,20 We have isolated two point mutations that enhance adenoviral release: E3/19K-445A and iLG397T, but they had no additive effect. Although almost all the virus produced is released, AdiLG397T-445A-RGD presented a significant loss in viral production. As it has been suggested by Wodarz, it is possible that maximizing the death rate of infected tumor cells could decrease viral production and result in a suboptimal outcome of the treatment.34

Adenovirus is a highly immunogenic virus. The interactions of the virus with host defenses will highly influence the outcome of the therapy.35 In relation to its immunogenicity, the effect of the early release remains to be studied. On one hand, it is conceivable that the presence of more extracellular virus could trigger a stronger innate response and, in turn, boost a stronger adaptative antiviral response leading to a faster clearance of the virus.26 On the other hand, Tollefson et al. hypothesized that the quicker the virus is released from the infected cell, the less chance the virus has of being killed in the cell by cytotoxic T lymphocytes, NK cells, and phagocytic cells, and consequently the greater chance it has to infect another cell.30 Contrary to the i-leader mutants, most enhanced-release mutants have their immunomodulatory functions compromised due to total or partial deletions in the E3 region functions.17,18,31,36,37 This region has been described to be dispensable for in vitro replication but in vivo the deletion of some of these proteins reduce the persistence of adenovirus and induce macrophage infiltration and expression of tumor necrosis factor and interferon-γ.38,39 Since the current knowledge of the i-leader truncated mutant seems to indicate that the immunoregulatory proteins of this virus are fully functional, this mutant will allow us to study the effect of improved release on the antitumor potency in immunocompetent models which will be a hallmark for the translation application of release enhancing modifications.

Our in vivo results show the i-leader truncation enhances antitumor activity of adenovirus and consequently holds great promise for tumor virotherapy in patients. To this end, we are currently introducing iLG397T mutation to an oncolytic adenovirus designed to replicate in the presence of an altered pRb pathway. Such virus, controls the expression of E1A-δ24 from the endogenous E1A promoter, rendering tumor selectivity through the insertion of palindromic E2F-binding sites (ICOVIR-15).40 Since i-leader expression is controlled by E1A, its truncation will increase the potency of the oncolytic adenovirus in tumor cells, and in CAFs if they are permissive to replication of the oncolytic virus due to an active proliferative status. Finally the combination of mutations that enhance adenovirus release, especially in CAFs, and strategies to degrade the ECM, such as the expression of hyaluronidases,13,14 might be useful to coordinately disrupt the antitumor barriers and increase adenovirus spread within the tumor mass. Such advances warrant improved therapeutic index of the adenovirus for the treatment of cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and recombinant adenovirus. Human embryonic kidney 293, A549 lung adenocarcinoma, and Skmel-28 melanoma cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Human fibroblasts were kindly provided by A. Tugores (Almirall-Prodesfarma, Barcelona, Spain). CAF-1 cells (human carcinoma-associated fibroblasts, kindly provided by Dr G. Molleví) primary cell lines were isolated and established in our laboratory from hepatic metastasis of human colorectal carcinoma41 and were maintained with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin.

Adwt (human adenovirus 5, Ad5) was obtained from the ATCC. AdwtRGD, AdTL, AdE3/19K-445A have been previously described.18,42,43 AdE1B/19Kdel contains a frameshift A insertion in the position 1,885 that introduces a stop codon at amino acid 59 leading to the truncation of E1B/19K protein; additionally the virus includes a G to A point mutation at position 2,350 that cause a Cys to Tyr change in the amino acid 110 of the E1B/55K protein.

Random mutagenesis and in vitro selection. An AdwtRGD purified stock was randomly mutagenized with nitrous acid23 for 6 minutes (500-fold decrease in virus viability). CAF-1 monolayers were infected with the mutagenized stock at multiplicity of infection of 1 pfu/cell. When early CPE appeared, the SN was collected and used to reinfect new CAF-1 monolayers. Six rounds of reinfection were performed and individual clones were isolated by plaque-isolation in A549 cells.

Construction of Adclone#2/Adwt recombinant and E3/19K modified viruses. Plasmids were generated by homologous recombination in yeast. The URA3 selectable marker in pAd5CAU18 was exchanged for LEU gene generating pAd5CALdSwa. Plasmids were constructed in a two-step, positive-negative selection method using LEU and URA3 genes for positive selection and URA3 gene + 5-fluoro-orotic acid (Fermentas Life Science, Vilnius, LT) for negative selection. Plasmids substituting regions from 338 to 13,036, from 11,689 to 27,016 and from 24,001 to 35,741 of Adwt genome for URA3 gene were generated. Then URA3 was exchanged for the equivalent region of the Adclone#2 genome, as indicated schematically in Figure 2, to obtain pAdR1, pAdR2, and pAdR3. pAdiLG397T-RGD-CAL was constructed by homologous recombination between CAL backbone sequence and the AdiLG397T-RGD genome. Two-step positive-negative selection method was also used to introduce the E3/19K-445A mutation to generate pAdiLG397T-445A-RGD-CAL. All modifications were confirmed by sequencing. The Adclone#2 genome and generated recombinants were sequenced using oligonucleotides specially designed to cover the whole genome and the specific mutations. Viruses were generated by transfection in HEK293 cells, further amplified in A549 cells, purified on CsCl gradients according to standard techniques and titered using an anti-hexon staining-based method.44

Virus release and production assays. CAF-1 and A549 monolayers seeded in 24-well plates were infected in triplicates at 40 transducing units (TU)/cell for CAF-1 and 20 TU/cell for A549 of the indicated virus to allow 80–100% infection. Four h.p.i, medium was removed and cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with fresh medium (DMEM 5% FBS alone or containing 20 µmol/l Q-VD-OPh (Merck, Darmstadt, DE). At the indicated time points samples of SN (containing the released virus) and CE (containing the total amount of virus produced) were collected. Virus was quantified by an anti-hexon staining-based method in HEK293 cells. The two-tailed Student's t-test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences in virus release and production between different viruses.

Plaque-assay and cell plaque-assay. A549 monolayers seeded in 6-well plates were infected with serial dilutions of the indicated virus. Four h.p.i. the medium was removed and cells were covered with a 1:1 mix of DMEM 5% FBS:1% agarose. Once agarose solidified, DMEM 5% FBS alone or containing Q-VD-OPh 20 µmol/l (final concentration 10 µmol/l) was added. To study the plaque size, 7 days after infection monolayers were stained by incubation with 0.5 mg/ml thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 37 ºC and 5% CO2 for 4 hours. To perform a cell plaque assay, A549 cells were coinfected with the indicated virus at 40 TU/cell for each virus. Four h.p.i., medium was removed and cells were washed three times with PBS and trypsinized. Serial dilutions of these cells were cocultured with new A549 monolayers in 6-well plates and continued with the standard plaque assay protocol.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay. CAF-1 (5 × 103), human fibroblasts (1 × 104), A549 (3 × 104), and SkMel-28 (1.5 × 104) cells were seed in 96-well plates and infected in suspension with serial 1/3 (for CAF-1, human fibroblasts, and SkMel-28) or 1/5 (for A549) dilutions of the indicated viruses starting from 200 TU/cell (CAF-1, human fibroblasts and A549) or 266 TU/cell (for SkMel-28). At day 11 postinfection (for CAF-1 and human fibroblasts), dead cells were quantified incubating plates with 15 µl of Alamar Blue (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) for 8 hours at 37 °C and the fluorescence was read with EX 525 EM 580–640 filter with Promega GloMax-Multi+ Detection System (Promega, Madison, WI). At day 5 (for A549) and 6 (for SkMel-28) cells were washed with PBS and stained for total protein content with bicinchoninic acid (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and absorbance was quantified after 30-minute incubation. IC50 values were calculated from dose–response curves by standard nonlinear regression (GraFit; Erithacus Software, Horley, UK) using an adapted Hill equation. The two-tailed Student's t-test was used to study the statistical significance of the IC50 differences between both viruses.

Caspase-3 activity assay. A549 cells were mock infected, infected with 20 TU/cell (80–100% infection) of the indicated virus, or treated with staurosporine (Sigma-Aldrich) 2 µmol/l. After 4 hours, the medium was removed and cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with fresh medium (DMEM 2% FBS). At the indicated time points samples were collected. The cell lysates were prepared with lysis buffer (5 mmol/l Tris–HCl (pH = 8), 20 mmol/l EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100). Total protein was quantified by Bradford staining. To quantify caspase-3 activity, 20 µg of cell lysates were incubated with 150 µl of reaction buffer [20 mmol/l HEPES (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 2 mmol/l DTT] and 2 µg of Ac-DEVD-AMC for 1 hour at 37 °C. Then the fluorescence was measured with Promega GloMax-Multi+ Detection System (UV filter). The two-tailed Student's t-test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences in caspase-3 activity between different viruses.

Evaluation of antitumor efficacy in vivo. In vivo studies were performed at the ICO-IDIBELL facility (Barcelona, Spain) AAALAC unit 1,155, and approved by the IDIBELL's Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation. For the establishment of mix lung carcinoma and human fibroblasts tumor xenograft model, 5 × 106 A549 cells + 1 × 106 human fibroblasts or 1 × 106 A549 cells + 3 × 106 human fibroblasts mix tumor xenografts were subcutaneously implanted in both flanks on Rag-1KO 8-weeks-old mice. To evaluate antitumor activity, lung carcinoma A549 or a mix of lung carcinoma A549 cells and human fibroblasts tumor xenografts were established by subcutaneous injection of 3 × 106 A549 cells alone or 1 × 106 A549 cells + 1 × 106 human fibroblasts into the flanks of 8-week-old male BAlb/C nu/nu mice. When tumors reached 100 mm3, mice were randomized (n = 8–10 tumors per group) and treated with a single intravenous injection of PBS or 2.3 × 1010 vp of AdwtRGD or AdiLG397T-RGD by tail vein. The vp/TU ratio of the purified stocks was 16.75 for AdwtRGD and 15.25 for Adclone#2. Tumor size and mice weight was measured twice a week. Tumor volume was calculated according to the Equation V (mm3) = π/6 × W × L2, where W and L are the width and the length of the tumor, respectively. The two-tailed Student's t-test was used to study the statistical significance of the differences in the tumor volume of the different treatment groups. For Kaplan–Meier survival curves, end-point was established at a tumor volume ≥500 mm3. The animals whose tumor size never reached the threshold were included as right censored information. A log-rank test was used to determine the statistical significance of the differences in time-to-event.

Immunohistochemical detection of human fibroblasts and adenovirus E1A protein in xenograft tumors. OCT-embedded sections of the A549/human fibroblasts tumors were incubated with antifibroblast antigen mouse mAb (clone AS02; Calbiochem, Darmstadt, DE) specific for human fibroblasts and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) antibodies, and counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole. OCT-embedded sections of A549/human fibroblasts tumors at the end of the efficacy experiment were incubated with anti-adenovirus-2/5 E1A (13S-5) SC-430 rabbit polyclonal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen Molecular Probes) antibodies and counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole. For immunohistochemical detection paraffin-embedded sections of A549/human fibroblasts tumors from the efficacy experiment at day 19 postinjection were deparaffinized, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation for 30 minutes in 3% H2O2 in PBS and antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer. After rehydration, sections were blocked for 30 minutes with 20% normal goat serum diluted in PBS 1% BSA. For human fibroblast staining, the slides were incubated with mouse anti-vimentin (clone V9) primary antibody (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) overnight at 4 °C. After primary antibody incubation the slides were washed in PBS 0.2% triton X-100 and incubated with EnVision (Dako, Hamburg, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After washings, sections were developed with DAB (Dako Laboratories, Glostrup, Denmark), and counterstained with hematoxylin. For E1A immunohistochemical detection rabbit anti-adenovirus-2/5 E1A (13S-5) SC-430 rabbit polyclonal IgG and EnVision were used. Images of sections were obtained on an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope (Olympus America, Melville, NY).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD present the same toxicity profile. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Blanca Luena for her technical assistance in animal experiments, Mercè Juliachs and Rafael Moreno for their technical assistance. We also acknowledge David Garcia Molleví for providing CAF-1 primary cell line and for his technical assistance. C.P.-S. was supported by a master grant from “La Caixa” and a predoctoral fellowship (PFIS) granted by the “Instituto de Salud Carlos III”. This work was supported by PI08/1661 FIS grant from the “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” of the Government of Spain (M.C.), a BIO2008-04692-C03-01 grant from the “Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología” of the Government of Spain (R.A.), a 2009SGR283 research grant from the “Generalitat de Catalunya” (R.A.), and by Mutua Madrileña Medical Research Foundation (M.C.). R.A. belongs to the Network of Cooperative Research on Cancer (C03-10), “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” of the Government of Spain.

Supplementary Material

AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD present the same toxicity profile.

REFERENCES

- Liu TC, Galanis E., and, Kirn D. Clinical trial results with oncolytic virotherapy: a century of promise, a decade of progress. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:101–117. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss R., and, Lieber A. Anatomical and physical barriers to tumor targeting with oncolytic adenoviruses in vivo. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2009;11:513–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TC, Hwang TH, Bell JC., and, Kirn DH. Translation of targeted oncolytic virotherapeutics from the lab into the clinic, and back again: a high-value iterative loop. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1006–1008. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R., and, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micke P., and, Ostman A. Exploring the tumour environment: cancer-associated fibroblasts as targets in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:1217–1233. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MV, Viale DL, Cafferata EG, Bravo AI, Carbone C, Gould D.et al. (2009Tumor associated stromal cells play a critical role on the outcome of the oncolytic efficacy of conditionally replicative adenoviruses PLoS ONE 4e5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauthoff H, Hu J, Maca C, Goldman M, Heitner S, Yee H.et al. (2003Intratumoral spread of wild-type adenovirus is limited after local injection of human xenograft tumors: virus persists and spreads systemically at late time points Hum Gene Ther 14425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wein LM, Wu JT., and, Kirn DH. Validation and analysis of a mathematical model of a replication-competent oncolytic virus for cancer treatment: implications for virus design and delivery. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1317–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva LR, Binny C, Ferreira SC., Jr, and, Martins ML. A multiscale mathematical model for oncolytic virotherapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1205–1211. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont JP, Nemunaitis J, Kuhn JA, Landers SA., and, McCarty TM. A prospective phase II trial of ONYX-015 adenovirus and chemotherapy in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (the Baylor experience) Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:588–592. doi: 10.1007/BF02725338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso MM, Gomez-Manzano C, Jiang H, Bekele NB, Piao Y, Yung WK.et al. (2007Combination of the oncolytic adenovirus ICOVIR-5 with chemotherapy provides enhanced anti-glioma effect in vivo Cancer Gene Ther 14756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros A, Puig C, Guedan S, Rojas JJ, Alemany R., and, Cascallo M. Verapamil enhances the antitumoral efficacy of oncolytic adenoviruses. Mol Ther. 2010;18:903–911. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh S, Gonzalez Edick M, Idamakanti N, Abramova M, Vanroey M, Robinson M.et al. (2007Relaxin-expressing, fiber chimeric oncolytic adenovirus prolongs survival of tumor-bearing mice Cancer Res 674399–4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedan S, Rojas JJ, Gros A, Mercade E, Cascallo M., and, Alemany R. Hyaluronidase expression by an oncolytic adenovirus enhances its intratumoral spread and suppresses tumor growth. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1275–1283. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., and, Curiel DT. Current issues and future directions of oncolytic adenoviruses. Mol Ther. 2010;18:243–250. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TC, Hallden G, Wang Y, Brooks G, Francis J, Lemoine N.et al. (2004An E1B-19 kDa gene deletion mutant adenovirus demonstrates tumor necrosis factor-enhanced cancer selectivity and enhanced oncolytic potency Mol Ther 9786–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doronin K, Toth K, Kuppuswamy M, Ward P, Tollefson AE., and, Wold WS. Tumor-specific, replication-competent adenovirus vectors overexpressing the adenovirus death protein. J Virol. 2000;74:6147–6155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6147-6155.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros A, Martínez-Quintanilla J, Puig C, Guedan S, Molleví DG, Alemany R.et al. (2008Bioselection of a gain of function mutation that enhances adenovirus 5 release and improves its antitumoral potency Cancer Res 688928–8937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Kitzes G, Dormishian F, Hawkins L, Sampson-Johannes A, Watanabe J.et al. (2003Developing novel oncolytic adenoviruses through bioselection J Virol 772640–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian T, Vijayalingam S., and, Chinnadurai G. Genetic identification of adenovirus type 5 genes that influence viral spread. J Virol. 2006;80:2000–2012. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.2000-2012.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoff A, Rivera AA, Banerjee NS, Mathis JM, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, Le LP.et al. (2006Strategies to enhance transductional efficiency of adenoviral-based gene transfer to primary human fibroblasts and keratinocytes as a platform in dermal wounds Wound Repair Regen 14608–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Fueyo J, Krasnykh V, Reynolds PN, Curiel DT., and, Alemany R. A conditionally replicative adenovirus with enhanced infectivity shows improved oncolytic potency. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:120–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JF, Gharpure M, Ustacelebi S., and, McDonald S. Isolation of temperature-sensitive mutants of adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1971;11:95–101. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-11-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilder S, Logan J., and, Shenk T. Deletion of the gene encoding the adenovirus 5 early region 1b 21,000-molecular-weight polypeptide leads to degradation of viral and host cell DNA. J Virol. 1984;52:664–671. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.2.664-671.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott JA, Nilsson E, Mosher R, Magrane G, Albertson D, Pinkel D.et al. (2001Stromal-epithelial interactions in the progression of ovarian cancer: influence and source of tumor stromal cells Mol Cell Endocrinol 17529–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros A, Guedan S. Adenovirus release from the infected cell as a key factor for adenovirus oncolysis. The Open Gene Therapy Journal. 2010;3:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger C, Ellenrieder V, Alber B, Lacher U, Menke A, Hameister H.et al. (1999Expression and differential regulation of connective tissue growth factor in pancreatic cancer cells Oncogene 181073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloway PD., and, Shenk T. The adenovirus type 5 i-leader open reading frame functions in cis to reduce the half-life of L1 mRNAs. J Virol. 1990;64:551–558. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.551-558.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington JS, Lucher LA, Brackmann KH, Virtanen A, Pettersson U., and, Green M. Biosynthesis of adenovirus type 2 i-leader protein. J Virol. 1986;57:848–856. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.848-856.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson AE, Scaria A, Hermiston TW, Ryerse JS, Wold LJ., and, Wold WS. The adenovirus death protein (E3-11.6K) is required at very late stages of infection for efficient cell lysis and release of adenovirus from infected cells. J Virol. 1996;70:2296–2306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2296-2306.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra M, Rahman A, Zou A, Vaillancourt M, Howe JA, Antelman D.et al. (2001Re-engineering adenovirus regulatory pathways to enhance oncolytic specificity and efficacy Nat Biotechnol 191035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauthoff H, Heitner S, Rom WN., and, Hay JG. Deletion of the adenoviral E1b-19kD gene enhances tumor cell killing of a replicating adenoviral vector. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:379–388. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beusechem VW, van den Doel PB, Grill J, Pinedo HM., and, Gerritsen WR. Conditionally replicative adenovirus expressing p53 exhibits enhanced oncolytic potency. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6165–6171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz D. Viruses as antitumor weapons: defining conditions for tumor remission. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3501–3507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemany R., and, Cascallo M. Oncolytic viruses from the perspective of the immune system. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:527–536. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CO, Kim E, Koo T, Kim H, Lee YS., and, Kim JH. ADP-overexpressing adenovirus elicits enhanced cytopathic effect by induction of apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12:61–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson AE, Scaria A, Ying B., and, Wold WS. Mutations within the ADP (E3-11.6K) protein alter processing and localization of ADP and the kinetics of cell lysis of adenovirus-infected cells. J Virol. 2003;77:7764–7778. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7764-7778.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hallden G, Hill R, Anand A, Liu TC, Francis J.et al. (2003E3 gene manipulations affect oncolytic adenovirus activity in immunocompetent tumor models Nat Biotechnol 211328–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolanza S, Bunuales M, Alzuguren P, Lamas O, Aldabe R, Prieto J.et al. (2009Deletion of the E3-6.7K/gp19K region reduces the persistence of wild-type adenovirus in a permissive tumor model in Syrian hamsters Cancer Gene Ther 16703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas JJ, Guedan S, Searle PF, Martinez-Quintanilla J, Gil-Hoyos R, Alcayaga-Miranda F.et al. (2010Minimal RB-responsive E1A promoter modification to attain potency, selectivity, and transgene-arming capacity in oncolytic adenoviruses Mol Ther 181960–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molleví DG, Aytes A, Berdiel M, Padullés L, Martínez-Iniesta M, Sanjuan X.et al. (2009PRL-3 overexpression in epithelial cells is induced by surrounding stromal fibroblasts Mol Cancer 846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev I, Krasnykh V, Miller CR, Wang M, Kashentseva E, Mikheeva G.et al. (1998An adenovirus vector with genetically modified fibers demonstrates expanded tropism via utilization of a coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-independent cell entry mechanism J Virol 729706–9713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemany R., and, Curiel DT. CAR-binding ablation does not change biodistribution and toxicity of adenoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1347–1353. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascallo M, Gros A, Bayo N, Serrano T, Capella G., and, Alemany R. Deletion of VAI and VAII RNA genes in the design of oncolytic adenoviruses. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:929–940. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AdwtRGD and AdiLG397T-RGD present the same toxicity profile.