Abstract

The zwitterionic phospho-form moieties phosphoethanolamine (PE) and phosphocholine (PC) are important components of bacterial membranes and cell surfaces. The major type IV pilus subunit protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, PilE, undergoes posttranslational modifications with these moieties via the activity of the pilin phospho-form transferase PptA. A number of observations relating to colocalization of phospho-form and O-linked glycan attachment sites in PilE suggested that these modifications might be either functionally or mechanistically linked or interact directly or indirectly. Moreover, it was unknown whether the phenomenon of phospho-form modification was solely dedicated to PilE or if other neisserial protein targets might exist. In light of these concerns, we screened for evidence of phospho-form modification on other membrane glycoproteins targeted by the broad-spectrum O-linked glycosylation system. In this way, two periplasmic lipoproteins, NGO1043 and NGO1237, were identified as substrates for PE addition. As seen previously for PilE, sites of PE modifications were clustered with those of glycan attachment. In the case of NGO1043, evidence for at least six serine phospho-form attachment sites was found, and further analyses revealed that at least two of these serines were also attachment sites for glycan. Finally, mutations altering glycosylation status led to the presence of pptA-dependent PC modifications on both proteins. Together, these results reinforce the associations established in PilE and provide evidence for dynamic interplay between phospho-form modification and O-linked glycosylation. The observations also suggest that phospho-form modifications likely contribute biologically at both intracellular and extracellular levels.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial surface and membrane-associated proteins play important roles in interactions between microbes, with hosts, and with inanimate or other surface structures. As such, a comprehensive knowledge of the structure and chemistry of these proteins is desirable to fully understand the nature, ecology, and evolution of such interactions. In addition to features generated by primary sequence, folding and protein-protein interactions, covalent posttranslational modifications (PTMs) also provide potential sources for structural and functional diversity. Such PTMs on proteins are important components of biological systems as modulators of protein properties and functions. The predominant surface organelles flagella and type IV pili (Tfp) are frequently subject to protein glycosylation, although the significance of these modifications is only beginning to be appreciated. The study of PTM systems might therefore elucidate important aspects of microbial biology.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative human pathogen and the causative agent of gonorrhea. The cell surface of N. gonorrhoeae contains highly variable and complex structures such as lipooligosaccharide (LOS) and type IV pili (Tfp), which are important for pathogenesis. PilE, the major subunit of Tfp in N. gonorrhoeae, is posttranslationally modified by O-linked oligosaccharides up to three sugar residues in length. The glycan modification on N. gonorrhoeae PilE is part of a general glycosylation system that targets at least 12 periplasmic proteins of various cellular functions (2, 35). In addition, PilE undergoes phospho-form modification defined as the addition of either phosphoethanolamine (PE) or phosphocholine (PC), at defined serine residues (1, 17, 35). Both glycan and phospho-form modifications are predicted to be located at the surface of the assembled pilus (26). Phospho-form modifications of PilE were first recognized in association with modification with both PE and PC in a mutant background lacking PilV, a minor pilin-like protein important for host cell attachment (1, 17, 37). Previous studies of PilE phospho-form modification identified the pilin phospho-form transferase A protein (PptA) as a PE transferase essential for phospho-form modifications (25). PptA shares multiple structural features with E. coli EptB and related proteins that comprise a subfamily of the larger alkaline phosphatase superfamily that modify lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with PE. Cj0256, a pEtN/PE transferase member of this group identified in the enteric pathogen Campylobacter jejuni, modifies two periplasmic substrates: lipid A and the flagellum-associated FlgG protein (11). Moreover, a C. jejuni mutant lacking Cj0256 is defective in flagellar expression and function. Although it is reported that pilin glycan is important for gonococcal binding to complement receptor 3 (19), the evolutionary advantage conferred by gonococcal protein glycosylation and phospho-form modifications remains to be elucidated.

Both PE and PC are zwitterionic molecules commonly found as polar head groups on lipids and as modifications on surface glycans. As intrinsic parts of the bacterial surface architecture, PE and PC are implicated in a variety of host-microbe interactions (6, 16, 21, 29). PC moieties on the bacterial surfaces have been shown to increase bacterial epithelial and endothelial cell adherence, persistence, and invasion by important pathogens and commensals, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria spp. by binding to the platelet-activating factor receptor (PAF-R) (12, 29, 30, 33). Moreover, the PC moiety is recognized by PC-recognizing antibodies (7) as well as by C-reactive protein (CRP), a protein important in opsonization and complement-dependent clearance mechanisms (22). In addition, PE and PC on bacterial LPS have been implicated in resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (16, 21, 34).

In this study, we show that the PptA-dependent protein phospho-form modification system of N. gonorrhoeae modifies at least two proteins in addition to PilE and that it, like the general protein glycosylation system, has broader target specificity than previously thought. We also demonstrate that the phospho-form modification system and the general O-linked glycosylation system of N. gonorrhoeae have partially overlapping occupancy site specificities and that protein glycosylation can affect phospho-form modification status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this work are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material and were grown on conventional GC medium (2). Carboxy-terminal 6His-tagged alleles were generated as previously described (35). pptA (ngo1540) null mutations were introduced by transformation with lysate from strain GD1 (pptA::cm) (1) or KS9 (pptA::kan) (25) and selection for chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml)- or kanamycin (50 μg/ml)-resistant transformants. The mutant alleles pglO::kan (ngo0096; resulting in strains missing the oligosaccharyl transferase responsible for glycan attachment to proteins), pglC::kan (ngo0084; resulting in strains producing no lipid-linked glycan), and pilV::kan (ngo0543; resulting in strains lacking the minor pilin-like protein) were introduced into various strain backgrounds by transformation with lysate from strains as described previously (35) and selection for kanamycin-resistant transformants. Strains expressing pglEON (ngo0207) were generated as described previously (2).

Construction of the pglCfs mutant.

To create the pglCfs frameshift mutation, a pglC fragment was PCR amplified from strain N400 with the primers pglC5′ and pglC3′ and cloned into the vector pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen) to create the plasmid pTOPOpglC. (The primers used in this work are described in Table S2 in the supplemental material.) The plasmid was linearized with the AscI restriction enzyme, which cuts at bp 785 of the pglC open reading frame, followed by a fill-in reaction to create a frameshift mutation in pglC. The pglCfs mutation was introduced into N. gonorrhoeae by nonselective transformation (15), and transformants were screened by PCR and loss of the restriction site AscI.

Construction of the pglAfs mutant.

A frameshift mutation in pglA (ngo1765) was introduced through a two-step mutagenesis strategy using the ermC′/rpsL+ counterselectable marker in plasmid pFLOB4300 (20). First, upstream and downstream sequences of pglA were PCR amplified and cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites on each side of the counterselectable marker. The upstream sequence (1,035 bp) was PCR amplified with primers F-EcoRI and R-EcoRI, and the downstream sequence (833 bp) was amplified with primers F-HindIII and R-HindIII. Sequencing verified that these flanking sequences were inserted in the same orientation in the final plasmid pFLOB4300-pglA::ermC′/rpsL+. This plasmid was transformed into strain 4/3/1, where the selection cassette replaced pglA in the erythromycin (8 μg/ml)-resistant gonococci that were selected. Strain 4/3/1 is naturally streptomycin resistant, but introduction of the rpsL+ allele made the intermediate strain, 4/3/1 pglA::ermC′/rpsL+, streptomycin sensitive. Then, pglA (3,734 bp, including upstream and downstream sequences) was PCR amplified from strain FA1090 with primers F-EcoRI and R-HindIII and cloned into pCRII-TOPO. Subsequent sequencing identified one plasmid with a frameshift (10 G) in the poly(G) tract of pglA. This plasmid, pCRII-pglAfs, was transformed into the 4/3/1 pglA::ermC′/rpsL+ strain, and correct transformants, containing pglAfs in place of the counterselectable marker, were selected on streptomycin plates (750 μg/ml).

Protein purification.

6His-tagged proteins were purified using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) beads (Qiagen) as described previously (35) except without the inclusion of the proteinase inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Procedures for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting were as previously described (14). 6His-tagged proteins were detected by using an anti-tetra-His mouse monoclonal antibody at a 1:1,000 dilution (Qiagen). For glycan detection, 1:10,000 dilutions of rabbit monoclonal antibodies against monosaccharide (npg-1), disaccharide (npg-2), and trisaccharide (npg-3) were employed (4). Detection of PC-modified proteins was done by using a mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb), TEPC-15, at 1:750 dilution (Sigma). Secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Qiagen) for the npg antibodies or goat anti-mouse antibodies (Sigma) for the tetra-His antibodies, both at 1:2,000 dilutions. For PC detection, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Sigma) were used at a 1:1,000 dilution. HRP detection and visualization were done using SuperSignal West Dura extended-duration substrate (Thermo Scientific) and a Kodak Image Station 4000R.

MS2 CID and HCD analyses.

Coomassie-stained gel bands of purified proteins were washed and destained. After an alkylation reduction step, digestion was performed with either trypsin (Sigma) or AspN (Roche) at 37°C overnight. Generated peptides were subsequently extracted with 5% formic acid and acetonitrile and dried by SpeedVac as described previously (1). Dried samples were redissolved in 0.1% formic acid prior to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS2) analyses. The LC separation was performed on an Agilent 1200 series capillary high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. Five-microliter samples were injected onto the extraction column (5 by 0.3 mm filled with Zorbax 300 SB-C18 of 5-μm particle size; Agilent), before peptides were eluted in the back-flush mode from the extraction column onto the C18 reverse-phase column (0.075 by 150 mm, GlycproSIL C18-80 Å; Glycpromass, Stove, Germany). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. LC separation was achieved with a gradient from 5% to 60% of acetonitrile over 60 min employing a flow rate of 0.2 μl per min. The LC system was connected to a nanoelectrospray source of a Thermo Scientific LTQ OrbitrapXL mass spectrometer operated by Xcalibur 2.0. Nanospray ionization was achieved by applying 1.2 kV between an 8-μm-diameter emitter (PicoTip Emitter, New Objective, Woburn, MA) and the capillary entrance of the Orbitrap. The capillary temperature was set to of 200°C and the capillary voltage to 30 V. Mass spectra were acquired in positive-ion mode. The three most intense ions from one full survey scan at a resolution of 30,000 at m/z 400, were fragmented by higher-energy C-trap dissociation (HCD) at 35% normalized collision energy (R = 15,000). All Orbitrap analyses were performed with the lock mass option (lock mass, m/z 445.12003) for internal calibration. The ion selection threshold was 500 counts. Selected fragment ions were dynamically excluded for 120 s. Alternatively, collision-induced dissociation (CID) analyses of proteolytic peptides was performed using nanoflow liquid chromatographic MS2 analyses (nano-LC-chip MS2) on an Agilent 1100 LC/MSD Trap XCT Ultra system equipped with a Chip/MS Cube interface as previously described (35). MS2 data were used to search against the Swiss-Prot Proteobacteria protein sequence database utilizing the Mascot search engine (Matrix Sciences, London, United Kingdom) or alternatively an in-house-generated N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 protein database was searched using Proteome Discoverer 1.0 software with the SEQUEST search engine (Thermo Scientific). The mass tolerances of parent ions were set at 7 ppm, and those of fragment ions were set at 0.05 Da. Methionine oxidation was set as a variable modification, and cysteine carbamidomethylation was selected as a fixed modification. The enzyme settings were trypsin for NGO1043 and AspN for NGO1237, allowing one missed cleavage. Peptides with an M score of 38 and XCorr higher than 2.0 were considered significant. Modified peptides were manually inspected.

RESULTS

Evidence for phospho-form modification of NGO1043.

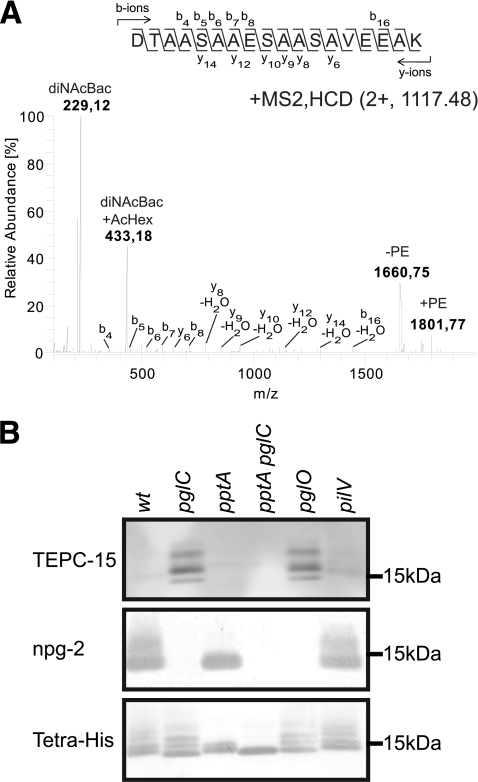

We previously reported that the lipoprotein designated NGO1043 (a homolog of N. meningitidis NMB1468, also known as Ag473) (10, 18, 32) is a target of the broad-spectrum O-linked glycosylation system (35). This conclusion was based on mass spectrometry (MS)-based identification of glycopeptides generated by tryptic digestion of an affinity-purified form of the protein. One of the glycopeptides corresponded to 38DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 of the protein. During that study, we observed MS2 spectra suggesting that this peptide might have another PTM in addition to the O-glycan. We therefore reexamined additional mass spectra of affinity-purified and trypsin-digested NGO1043-6His. As seen in Fig. 1A, an MS2 spectrum of the peptide 38DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55, determined by de novo sequencing, showed the reporter oxonium ion for the known di-N-acetylbacillosamine (diNAcBac)-acetylhexose disaccharide form at m/z 433.18 (35). However, the doubly charged precursor ion at m/z 1,117.48 (giving an observed mass of 2,233.96 Da [M+H+]) corresponded to the mass of the peptide 38DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 (theoretical monoisotopic mass, 1,678.78 Da [M + H+]) with diNAcBac-acetylhexose (theoretical mass, 432.18 Da) as well as a mass increase of 123.01 Da. Moreover, ions were detected at m/z 1,801.77, caused by the neutral loss of the glycan (432.18) from the precursor mass (2,233.96 Da), as well as at m/z 1,660.75 (representing the mass of dehydrated 38DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55), caused by the neutral loss of the glycan and an additional neutral loss of 141.03 Da from the precursor mass. Together, these data corresponded well with the presence of a PE moiety, as this modification previously has been shown to result in a mass increase of 123.01 Da to the peptide it modifies, as well as a neutral loss of 141.02 Da by fragmentation from the peptide backbone. The 18.01-Da difference between the 141.02-Da mass loss from the precursor peptide upon fragmentation and the 123.01-Da peptide mass increase upon PE attachment is due to the fact that PE attachment is a dehydration reaction associated with the loss of H2O (1, 11).

Fig 1.

Identification of glycan and phospho-form modifications of NGO1043. (A) The MS2 HCD spectrum of precursor peptide at m/z 1,117.98 [M + 2H]2+ confirmed that peptide 38DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 was modified with diNAcBac-acetylhexose and PE. The reporter oxonium ion of diNAcBac-acetylhexose at m/z 433.18 was detected. Moreover, the mass difference between the ions at m/z 1,801.77 [M + H]+ and m/z 1,660.75 [M + 1H]1+ represented a neutral loss of 141.02 Da, which corresponded to the loss of PE. MS analyses were performed on an LTQ OrbitrapXL mass spectrometer. (B) Immunoblots of purified NGO1043 from wild-type (wt), glycosylation-negative mutant (pglC), phospho-form transferase mutant (pptA), double mutant deficient for both PptA and PglC (pptA pglC), oligosaccharide transferase mutant (pglO), and minor pilin-like protein mutant (pilV) strains. Purified proteins were checked for reactivity against the TEPC-15 MAb (recognizing PC) and the npg-2 (recognizing the disaccharide glycan) and tetra-His antibodies.

We previously observed that phospho-form modifications had a subtle but reproducible effect on reducing the migration of PilE in SDS-PAGE. Since pptA is a PE transferase responsible for phospho-form modification of PilE (25), we asked if pptA status might have an impact on the relative migration of NGO1043. As a control, we included samples derived from backgrounds shown to alter PilE migration. As shown previously (35) and seen in Fig. 1B, NGO1043-6His was detected by immunoblotting as one major band with a trailing diffuse smear. However, in backgrounds completely defective in glycosylation, multiple discrete bands were observed. In a pptA-null background, these multiple species were reduced to two bands equal in migration to the wild-type background but without the trailing diffuse smear, whereas in a combined pglC pptA background, a single species of greater relative mobility was detected. Although there are no solid-phase-based methods for detecting PE, PC-bearing proteins can be identified by reactivity with the TEPC-15 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (36). We examined NGO1043-6His from various backgrounds and found pptA-dependent TEPC-15 reactivity in glycosylation null backgrounds (Fig. 1B). Protein glycosylation status was verified by immunoblotting using the npg-2 antibody that recognizes the disaccharide found in the wild-type strain (4). A previous study has shown that PilE modification with PE is enhanced in a mutant lacking the PilV pilin-like protein and that this effect is also accompanied by modification with PC, detectable by TEPC-15 reactivity (1). To determine if the effects associated with the absence of PilV were specific to PilE modification or if the absence of PilV affected phospho-form modification more generally, we examined TEPC-15 recognition of NGO1043-6His purified from a pilV mutant but found no evidence for reactivity (Fig. 1B). Together, these results suggested that NGO1043 undergoes multisite, phospho-form modification and demonstrated that the absence of glycosylation was associated with the ability to detect pptA-dependent PC modification of NGO1043.

Determination of PE modification sites on NGO1043 by MS and MS2 analyses.

As mentioned earlier, PE modification of proteins can be detected by MS due to the mass increase of 123.01 Da to the peptide mass. In fragmentation analyses, elimination of PE can also be detected as a neutral loss of 141.02 Da from the peptide mass. In the latter process, the modified serine is converted to a dehydroalanine (DHA), resulting in a peptide mass 18.01 Da less than the corresponding serine-containing peptide. Amino acid sequence determination of a peptide by fragmentation can therefore reveal the site of phospho-form modification by identifying the location of a serine to dehydroalanine conversion (1). Similarly, peptides carrying PC can be detected by the increase of 165.06 Da to the peptide mass and a loss of 183.07 Da from the peptide mass during fragmentation analyses and conversion of serine to dehydro-alianine (1).

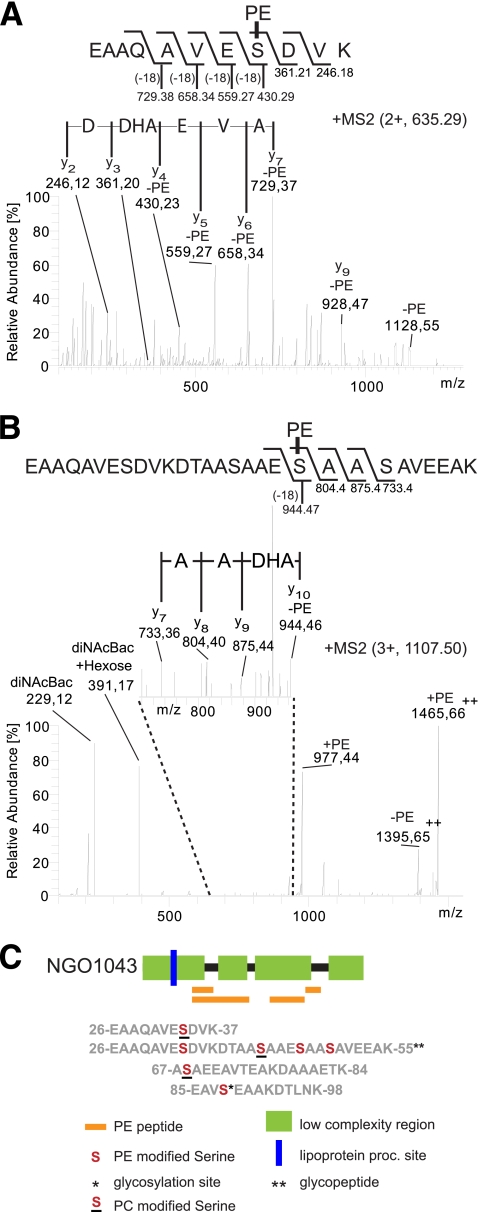

The multiple NGO1043 bands detected with TEPC-15 antibodies (Fig. 1B) led us to investigate the possibility of multiple phospho-form modifications. To identify additional phospho-form-modified peptides from NGO1043, we digested protein purified from a wild-type background with trypsin and analyzed the generated peptides by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS2). Several peptides with a mass increase of 123.01 Da larger than the theoretical peptide mass, indicating potential PE modifications, were detected (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The MS2 spectra of these peptides were subsequently examined, and by de novo sequencing of the peptide backbones, sites of phosphoethanolamine modification were detected by the occurrence of dehydroalanine (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 and Fig. S2).

Fig 2.

Identification of PE modification sites in NGO1043 by MS2. MS analyses were performed on an LTQ OrbitrapXL mass spectrometer. (A) MS2 spectrum of the PE-modified peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37 at m/z 635.29 [M + 2H]2+. A dehydroalanine (DHA) was detected at position y4 (m/z 430.23), identified by amino acid sequencing using the y-ion series from y2 to y7. Peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37 was modified with a PE at serine 34. (B) MS2 spectrum of glycan- and PE-modified peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 at m/z 1,107.50 [M + 3H]3+. A dehydroalanine (DHA) was detected at position y10 (m/z 944.46), by amino acid sequencing using the y-ion series from y7 to y10. Reporter ions for diNAcBac and diNAcBac-hexose were detected at m/z 229.12 and at m/z 391.17, respectively, confirming that peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 was modified with a PE at serine 49 and a glycan. (C) Phospho-form occupancy sites on NGO1043. Phospho-form-modified peptides (orange rectangles) and modification sites (in red) are shown. Underlining of sites denotes serines modified with a PC in a pglC background. Residues are numbered according to the unprocessed protein. Asterisks denote phospho-form-modified peptides shown to be simultanously modified by a glycan (two asterisks) or phospho-form-modified serines shown to be alternatively modified by a glycan (one asterisk). The blue line denotes the lipoprotein processing (proc.) site.

By searching for increased peptide masses, we detected the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37 modified with a PE. The precursor ion at m/z 635.29 (Fig. 2A; see Fig. S1A) corresponded to the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37 with a mass increase of 123.01 Da. The ion at m/z 1,128.55 corresponded to the complete peptide with a neutral loss of PE. By de novo sequencing of the peptide and analyses of y-ion series y2 to y7, a dehydroalanine was detected at position y4. This confirmed that for the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37, the PE modification was located at Ser34.

Similar analyses were done for 3 other peptides modified with PE, yielding 5 additional PE modification sites. Peptide 67ASAEEAVTEAKDAAAETK84 was modified with PE at Ser68 (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material), peptide 85EAVSEAAKDTLNK97 was modified by PE at Ser88 (see Fig. S1C), and a peptide with a single missed trypsin cleavage site, 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55, containing the 27EAAQAVESDVK37 sequence, was modified with a PE at Ser42 (Fig. S1D). Furthermore, in addition to being singly PE modified, the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 also could be found carrying both a glycan modification and a PE modification. As seen in Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A in the supplemental material, the precursor ion at m/z 1,107.50 corresponded to the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 with the diNAcBac-hexose glycan (390.16 Da) as well as the PE moiety. The presence of the glycan was evident in the low-mass area of the peptide spectrum as the oxonium reporter ions diNAcBac-hexose (m/z 391.17) and diNAcBac (m/z 229.12). Moreover, the ion at m/z 977.44 corresponded to the peptide with PE but without the glycan demonstrating that PE was attached to the peptide backbone and not to the glycan. De novo sequencing of the y-ion series y5 to y10 by fragmentation of the peptide backbone showed a dehydroalanine at y10, identifying a PE attachment site at Ser46. However, the glycan attachment site was not identified. The PE- and glycan-modified peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 was therefore PE modified on Ser46. Moreover, a second form of the PE- and glycan-modified peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 was detected and subjected to MS2 fragmentation and de novo sequencing (see Fig. S2B). This second PE- and glycan-modified form of peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 was PE modified on Ser49. This showed that the glycosylated peptide 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 could be PE modified on at least two sites, Ser46 and Ser49.

Since no TEPC-15 reactivity was detected with protein purified from pglC pptA double mutants and PptA is known to transfer PE onto PilE (1, 25), we asked if PptA was necessary for PE transfer onto NGO1043. We therefore analyzed and compared MS1 peptide elution chromatograms of NGO1043 from wild-type and pptA backgrounds. No peptides corresponding to the analyzed PE-modified peptides could be detected by MS1 analysis of peptides derived from NGO1043 purified from a pptA mutant (see Fig S3 and Fig S4 in the supplemental material). This suggested that PptA transferred PE onto NGO1043.

By MS and MS2 analysis of peptides from trypsin-digested NGO1043 from a pglC background and searching for peptides with a mass increase of 123.01 Da, all 6 serines modified with PE in a wild-type background were found to be modified with PE in a pglC background (see Fig S5 in the supplemental material). Moreover, by searching for increased peptide masses of 165.06 Da, we detected 3 serines modified with PC in a pglC background (see Fig S6 in the supplemental material). The peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37 was modified with a PC in a pglC background. The precursor ion at m/z 656.31 (see Fig. S6A) corresponded to the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37 with a mass increase of 165.06 Da. Moreover, the reporter ion at 184.1 Da, seen in the fragmentation spectrum, corresponds to PC. The ion at m/z 1,128.8 corresponded to the complete peptide with a neutral loss of PC. By de novo sequencing of the peptide and analysis of the y-ion series y2 to y7, a dehydroalanine was detected at position y4. This confirmed that for the peptide 27EAAQAVESDVK37, the PC modification was located at Ser34. Similar analyses were done for 2 other peptides modified with PC. Peptide 67ASAEEAVTEAK77 was modified with PC at Ser68 (see Fig. S6B), and a peptide with a single missed trypsin cleavage site, 27EAAQAVESDVKDTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55, was modified with PC at Ser42 (see Fig. S6C). This showed that all six serine sites modified with PE in the wild-type background were modified by PE in a pglC background. Moreover, at least 3 of these serines could also be detected carrying PC instead of PE in a pglC background. Since the modified serines could be detected with either PE or PC, there was no complete switch, but rather there existed a mixture of proteins carrying either PE or PC at the same residue in a pglC background.

As summarized in Fig. 2C, 6 serines in NGO1043 were detected with PE modifications: Ser34, Ser42, Ser46, Ser49, Ser68, and Ser88. Moreover, 3 serines were detected with PC modifications in a pglC background: Ser34, Ser42, and Ser68. Ser88 is previously identified as a glycosylation site (35). Ser88 may therefore be modified by either the N. gonorrhoeae general protein glycosylation system or the phospho-form modification system. Moreover, the phospho-form-modified serines Ser42, Ser46, and Ser49 all cluster within the peptide 36DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55, previously shown to be modified with two glycans (35). The peptide 36DTAASAAESAASAVEEAK55 contains only four possible glycosylation sites (Thr37, Ser42, Ser46, and Ser49). Therefore, at least one site, either Ser42, Ser46, or Ser49, must be capable of being modified with either PE or glycan. This demonstrates that there are at least 2 serines in NGO1043 that can serve as both phospho-form and glycan occupancy sites. It is also important to note that despite rigorous analyses, no evidence was seen for PC modification of NGO1043 in a wild-type background.

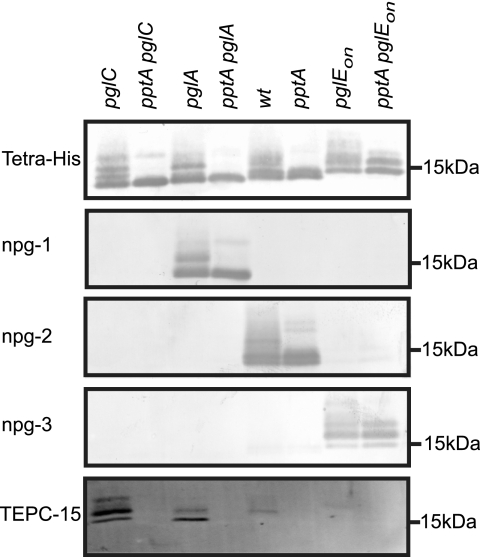

Effect of glycan length on phospho-form modification.

The Neisseria protein glycosylation system confers a high degree of heterogeneity in both oligosaccharide length and structure of the glycans attached (4, 5, 9, 27). We therefore investigated the potential effect of oligosaccharide length on PC modifications as detected with TEPC-15 MAb reactivity. As seen in Fig. 3, MAb reactivity could only be detected for NGO1043-6His purified from the pglC and pglA (expressing the monosaccharide diNAcBac glycan form) backgrounds, not for NGO1043-6His purified from the wild type (expressing disaccharide diNAcBac-acetylhexose) or pglEon (expressing trisaccharide diNAcBac-acetylhexose2) backgrounds. Correct glycosylation status was verified by immunoblotting using the npg-1, npg-2, and npg-3 monoclonal antibodies that recognize the mono-, di-, and trisaccharide glycan forms, respectively. This indicated that strong PC-specific MAb reaction was associated either with monosaccharide form or the absence of glycan. There is nonetheless a difference in the reaction pattern with MAb between the monosaccharide and glycan-negative samples. More reactive bands were present in the pglC lane than in the pglA lane, and the most intense band in the pglC background migrates slower than the most intense band in the pglA background.

Fig 3.

Effect of glycan length on the PC modification status of NGO1043. Shown are affinity-purified NGO1043-6His from a glycosylation-negative mutant (pglC), a double mutant deficient for both phospho-form transferase PptA and PglC (pptA pglC), a mutant producing monosaccharide (pglA), a double mutant producing monosaccharide and deficient for PptA (pptA pglA), a wild-type (wt) background, a phospho-form transferase mutant (pptA), a mutant producing trisaccharide (pglEon), and a double pptA pglEon mutant immunoblotted with antibodies against tetra-His, npg-1 (recognizing the monosaccharide glycan), npg-2 (recognizing the disaccharide glycan), and npg-3 (recognizing the trisaccharide glycan), as well as the TEPC-15 MAb (recognizing PC).

Phospho-form modification of NGO1237.

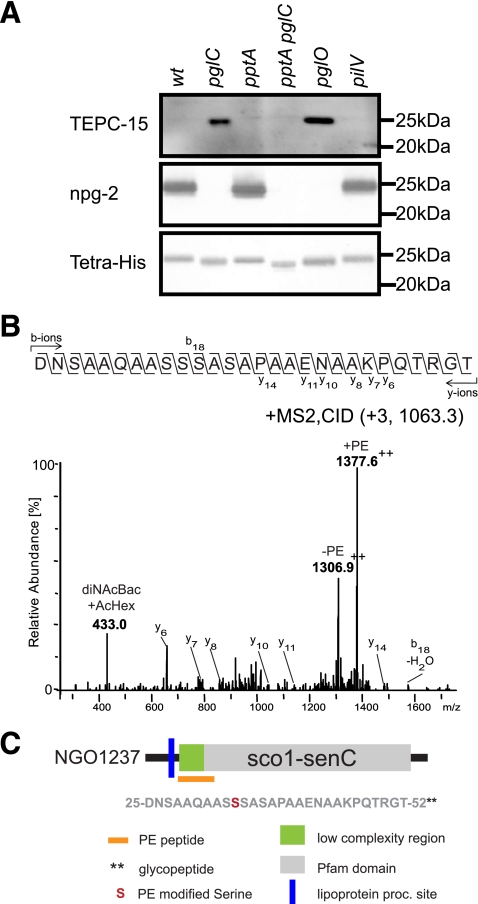

The phospho-form modification of glycoproteins NGO1043 and PilE led us to examine other glycoproteins for these modifications. Accordingly, we immunoblotted other affinity-purified glycoproteins derived from wild-type and glycosylation-negative (pglC) backgrounds using the TEPC-15 MAb. Of the 10 glycoproteins tested, only NGO1237 purified from the pglC background reacted with the PC-specific MAb in a pptA-dependent manner. NGO1237 is a lipoprotein and a member of the Sco/SenC/PrrC family, a protein family implicated in copper homeostasis and correct maturation of cytochrome c oxidase (3), in protection against oxidative stress (28), and in signal transduction (13). Phospho-form modification of NGO1237 was further investigated by immunoblotting of the protein derived from defined genetic backgrounds. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the relative mobility of the protein was increased in both the pglC, pglO, and in the pptA backgrounds, whereas it was even further enhanced in the pglC pptA double mutant. As seen for NGO1043, NGO1237 TEPC-15 reactivity was detected from a pglC background and was dependent on PptA. As was the case for the pglC mutant, reactivity with the TEPC-15 MAb was also detected in the pglO mutant. TEPC-15 MAb reactivity was not observed for NGO1237 purified from a pilV mutant, similar to what was found for NGO1043, indicating that the influence of PilV on phospho-form modification is limited to PilE. Taken together, these data showed that, as for NGO1043, the glycosylation status of NGO1237 had an impact on pptA-dependent TEPC-15 reactivity.

Fig 4.

Identification of phospho-form modification of NGO1237-6His. (A) NGO1237 was purified from a wild-type (wt) background, a glycosylation-negative mutant (pglC), a phospho-form transferase mutant (pptA), a double mutant deficient for both PptA and PglC (pptA pglC), an oligosaccharide transferase mutant (pglO), and a pilin-like protein mutant (pilV). All purified proteins were immunoblotted with the TEPC-15 MAb (recognizing PC) and antibodies against npg-2 (recognizing the disaccharide glycan) and tetra-His. (B) MS2 CID spectrum of the precursor peptide at m/z 1,063.3 [M + 3H]3+ confirmed that peptide 25DNSAAQAASSSASAPAAENAAKPQTRGT52 was modified with diNAcBac-acetylhexose and PE. The reporter oxonium ion of diNAcBac-acetylhexose disaccharide at m/z 433.0 could be detected. The charge-corrected difference between the ions at m/z 1,377.6 [M + 2H]2+ and m/z 1,306.9 [M + 2H]2+ represented the 141.02-Da neutral loss, indicative of a loss of PE. MS analyses were performed on an Agilent 1100 LC/MSD Trap XCT Ultra mass spectrometer. (C) Phospho-form modification site on NGO1237. The phospho-form-modified peptide was identified by MS2, and the location is indicated by an orange rectangle. Residues are numbered from unprocessed protein. Two asterisks denote that this is a phospho-form-modified peptide shown to be modified simultanously by a glycan.

By employing the three-dimensional (3D) ion trap for MS2 analyses, an AspN-derived peptide, 25DNSAAQAASSSASAPAAENAAKPQTRGT52, determined by de novo sequencing, from purified NGO1237-6His was detected with both a glycan modification and a PE modification. As shown in Fig. 4B, the triply charged precursor ion at m/z 1,062.3 (giving an observed mass of 3,184.9 Da [M + H+]) corresponded to the mass of the peptide 25DNSAAQAASSSASAPAAENAAKPQTRGT52 (theoretical mass, 2,630.2 Da [M + H+]) with disaccharide (theoretical mass, 432.0 Da) as well as a PE modification (theoretical mass, 123.0 Da). The reporter oxonium ion of the known N. gonorrhoeae diNAcBac-acetylhexose disaccharide at m/z 433 could be detected in the spectrum. Furthermore, the charge-corrected difference between the ions at m/z 1,377.6 (peptide with PE) and m/z 1,306.9 (dehydrated peptide) in the fragmentation spectrum represented a neutral loss of PE from the peptide backbone. Moreover, by de novo sequencing of the peptide 32ASSSASAPAAENAAKPQTRGT52 from a pglC background and analysis of the y-ion series y15 to y19, a dehydroalanine was detected at position y19. This confirmed that for the peptide 32ASSSASAPAAENAAKPQTRGT52, the PE modification was located at Ser34 (see Fig S7A in the supplemental material) in a pglC background. The peptide 25DNSAAQAASSSASAPAAENAAKPQTRGT52, located toward the N terminus of NGO1237, was therefore modified with both a glycan and a PE (Fig. 4C). Moreover, in a pglC background, a PE modification was identified at serine 34. No peptide corresponding to the analyzed PE-modified peptide could be detected in a pptA mutant (see Fig S7B). It is also important to note that as in the case of NGO1043, no MS-based evidence for PC modification of NGO1237 was seen when purified from the wild-type background.

DISCUSSION

Although phospho-form modifications are well-established substituents of bacterial surface glycoconjugates, direct modification of proteins with these moieties has only been described for the PilE pilin subunits of pathogenic Neisseria species and the FlgG protein of C. jejuni. In this work, we show that two additional proteins in N. gonorrhoeae also undergo covalent PE and PC modifications requiring the PptA phospho-form transferase. Although these new targets are neither structurally nor functionally related to PilE, they do share a number of commonalities. Like PilE, both NGO1043 and NGO1237 are trafficked within the periplasm, and similar to PilE in its unassembled state, both are membrane associated. Likewise, both NGO1043 and NGO1237 are targets of the general O-linked protein glycosylation system. Notably, sites of glycan and PE occupancy are at least partially clustered in all three instances. In the case of NGO1043, we found clear evidence that at least two serine residues could be modified by either glycan or PE. This finding demonstrates the potential for direct substrate competition between glycosylation and phospho-form modification at the level of occupancy sites.

Further evidence for interplay between glycosylation and phospho-form modification comes from the finding that mutations that blocked glycosylation led to an apparent switch in phospho-form modification status from PE to both PE and PC for both NGO1043 and NGO1237. Since these results were seen for mutants blocked in either synthesis of the undecaprenol-linked glycan or transfer of the glycan donor, these changes are likely attributable to protein glycosylation disruption per se and not indirect, off-pathway alterations. One caveat relating to interpreting the findings here involves the fact that PC was detected in part by reactivity with the MAb TEPC-15, which recognizes a PC-dependent epitope. Thus, one explanation might be that the glycan sterically blocks exposure of the PC epitope at adjacent sites. In such a scenario, the PC moieties are constitutively present but only accessible in the absence of the glycan or in the presence of the shortened monosaccharide form (found in the pglA background). However, the PC moiety was not detected in the MS analyses of either NGO1043 or NGO1237 derived from the wild-type glycosylated backgrounds. Alternatively, the absence of glycan or the presence of the truncated monosaccharide form leads to phospho-form microheterogeneity (i.e., the presence of both PE and PC moieties rather than just PE modifications). The latter scenario would be analogous to observations made for PilE in which there was clear evidence for a shift from just PE to a mixture of both PE and PC modifications in a background lacking the PilV protein, a pilin-like protein (1). However, the latter case was not associated with defective glycosylation of PilE. Also, PC modification of pilin was not seen in the PilE mutant in which its glycosylation was blocked (due to a serine-to-alanine substitution at the site of glycan occupancy (Ser63) (1). Conversely, we found here that a pilV-null mutation had no discernible effect on the PC modification status of either NGO1043 or NGO1237. Thus, the effects of altered glycosylation and PilV abrogation on PC elaboration are specific to the lipoproteins and PilE, respectively. We favor a model in which reactivity with MAb TEPC-15 directly correlates with the presence of a PC moiety and not alterations in epitope accessibility, and thus glycosylation status directly impacts phospho-form microheterogeneity. Still, further studies are needed to address this matter, particularly as different mechanisms may be operative for each individual protein.

Another interesting aspect of phospho-form modification here relates to the high number of occupancy sites observed for NGO1043, with six distinct serine residues in a span of 72 residues being modified. There also appears to be significant macroheterogeneity, as indicated by the multiple distinct forms detected in immunoblotting of NGO1043 derived from the pgl null backgrounds. As the slower-migrating species were detected by the TEPC-15 MAb in a pptA-dependent manner, they correspond to NGO1043 in at least three distinct forms differing in phospho-form modification valency. This conclusion is further buttressed by the MS data documenting differences in occupancy at specific serine residues within identical or overlapping peptides.

Although O-glycosylation of pilin has been reported to impact various aspects of pilus biology (19, 23, 24), the consequences of periplasmic protein glycosylation are only beginning to be addressed. Furthermore, as studies of protein phospho-form function are still in their infancy, it is particularly challenging to see what influence combined modifications might have. Interestingly, there is a well-described system of cross talk between posttranslational modifications in eukaryotes, where dynamic interplay between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins regulates signal transduction (38). Moreover, these modifications can either occupy the same or proximal sites competitively or occupy different sites noncompetitively. Whether or not glycan or phospho-form modifications of proteins in N. gonorrhoeae are dynamic in the sense of being reversible has yet to be determined. Nonetheless, it is not difficult to envision how cross talk involving these molecules might alter protein chemistry, antigenicity, and immunogenicity. Such perturbations might be particularly relevant to an abundant, surface-localized protein target such as PilE. It is also noteworthy in this context that Ag473, the NGO1043 orthologue of Neisseria meningitidis, has been touted as a potential vaccine candidate against meningococcal disease (10, 18, 32).

A third type of phospho-form modification utilizing a phosphoglycerol moiety was identified on serine residues in N. meningitidis pilin (31). This modification requires the product of the pptB gene (8). It will be interesting to see if phosphoglycerol modification is limited to pilin or if, like the case demonstrated here, multiple protein substrates exist.

Our findings raise important questions as to the full extent of gonococcal proteins undergoing phospho-form modification. This study was biased by its screening for expression of the PC epitope recognized by TEPC-15 among known glycoproteins. It thus missed those that might be modified only by PE as well as obviously overlooking potential glycoproteins yet to be identified. The TEPC-15 itself also has weaknesses as it has low sensitivity. For example, although this reagent detects PC-tagged NGO1043 and NGO1237 when enriched by purification, it fails to detect them in whole-cell lysates from the corresponding background. Screening for increased glycoprotein mobility (detected by MAb npg-2 reactivity in immunoblotting) in a pptA-null background revealed no other candidate substrates. This approach is also limited as the presence or absence of phospho-form modification might not visibly alter SDS-PAGE migration for higher-molecular-weight proteins. We find it likely that other PptA-targeted substrates exist but that their identification will require more intensive investigation.

In summary, this work documents that at least two other proteins in addition to PilE are subject to phospho-form modification and confirms that changes in phospho-form moieties can modulate protein antigenicity. Moreover, it extends both the association between protein glycosylation and phospho-form modification and their colocalization within protein substrates. Furthermore, the results show the potential for dynamic interplay between these two sets of modifications based on their shared sites of occupancy. Taken together with the established ability for neisserial strains to display intrastrain variability in glycan structure, the findings reveal a novel system for combinatorial diversification utilizing discrete covalent modifications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by Research Council of Norway grants 166931, 183613, and 183814 and by funds from GlycoNor, the Department of Molecular Biosciences and Center for Molecular Biology and Neurosciences of the University of Oslo.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 November 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aas FE, et al. 2006. Neisseria gonorrhoeae type IV pili undergo multisite, hierarchical modifications with phosphoethanolamine and phosphocholine requiring an enzyme structurally related to lipopolysaccharide phosphoethanolamine transferases. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 27712–27723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aas FE, Vik A, Vedde J, Koomey M, Egge-Jacobsen W. 2007. Neisseria gonorrhoeae O-linked pilin glycosylation: functional analyses define both the biosynthetic pathway and glycan structure. Mol. Microbiol. 65: 607–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balatri E, Banci L, Bertini I, Cantini F, Ciofi-Baffoni S. 2003. Solution structure of Sco1: a thioredoxin-like protein involved in cytochrome c oxidase assembly. Structure 11: 1431–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Børud B, et al. 2010. Genetic, structural, and antigenic analyses of glycan diversity in the O-linked protein glycosylation systems of human Neisseria species. J. Bacteriol. 192: 2816–2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Børud B, et al. 2011. Genetic and molecular analyses reveal an evolutionary trajectory for glycan synthesis in a bacterial protein glycosylation system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108: 9643–9648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brabetz W, Muller-Loennies S, Holst O, Brade H. 1997. Deletion of the heptosyltransferase genes rfaC and rfaF in Escherichia coli K-12 results in an Re-type lipopolysaccharide with a high degree of 2-aminoethanol phosphate substitution. Eur. J. Biochem. 247: 716–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Briles DE, Forman C, Crain M. 1992. Mouse antibody to phosphocholine can protect mice from infection with mouse-virulent human isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 60: 1957–1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chamot-Rooke J, et al. 2011. Posttranslational modification of pili upon cell contact triggers N. meningitidis dissemination. Science 331: 778–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chamot-Rooke J, et al. 2007. Alternative Neisseria spp. type IV pilin glycosylation with a glyceramido acetamido trideoxyhexose residue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104: 14783–14788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen H-W, et al. 2009. A novel technology for the production of a heterologous lipoprotein immunogen in high yield has implications for the field of vaccine design. Vaccine 27: 1400–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cullen TW, Trent MS. 2010. A link between the assembly of flagella and lipooligosaccharide of the Gram-negative bacterium Campylobacter jejuni. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107: 5160–5165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cundell DR, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Tuomanen EI. 1995. Streptococcus pneumoniae anchor to activated human cells by the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Nature 377: 435–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eraso JM, Kaplan S. 2000. From redox flow to gene regulation: role of the PrrC protein of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Biochemistry 39: 2052–2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freitag NE, Seifert HS, Koomey M. 1995. Characterization of the pilF-pilD pilus-assembly locus of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 16: 575–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gunn JS, Stein DC. 1996. Use of a non selective transformation technique to construct a multiply restriction/modification deficient mutant of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251: 509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harper M, et al. 2007. Decoration of Pasteurella multocida lipopolysaccharide with phosphocholine is important for virulence. J. Bacteriol. 189: 7384–7391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hegge FT, et al. 2004. Unique modifications with phosphocholine and phosphoethanolamine define alternate antigenic forms of Neisseria gonorrhoeae type IV pili. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101: 10798–10803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsu C-A, et al. 2008. Immunoproteomic identification of the hypothetical protein NMB1468 as a novel lipoprotein ubiquitous in Neisseria meningitidis with vaccine potential. Proteomics 8: 2115–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jennings MP, Jen FEC, Roddam LF, Apicella MA, Edwards JL. 2011. Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilin glycan contributes to CR3 activation during challenge of primary cervical epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 13: 885–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnston DM, Cannon JG. 1999. Construction of mutant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lacking new antibiotic resistance markers using a two gene cassette with positive and negative selection. Gene 236: 179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee H, Hsu FF, Turk J, Groisman EA. 2004. The PmrA-regulated pmrC gene mediates phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A and polymyxin resistance in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 186: 4124–4133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lysenko E, et al. 2000. The position of phosphorylcholine on the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae affects binding and sensitivity to C-reactive protein-mediated killing. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 234–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marceau M, Forest K, Beretti J, Tainer J, Nassif X. 1998. Consequences of the loss of O-linked glycosylation of meningococcal type IV pilin on piliation and pilus-mediated adhesion. Mol. Microbiol. 27: 705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marceau M, Nassif X. 1999. Role of glycosylation at Ser63 in production of soluble pilin in pathogenic Neisseria. J. Bacteriol. 181: 656–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naessan CL, et al. 2008. Genetic and functional analyses of PptA, a phospho-form transferase targeting type IV pili in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 190: 387–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parge HE, et al. 1995. Structure of the fibre-forming protein pilin at 2.6 Å resolution. Nature 378: 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Power PM, et al. 2003. Genetic characterization of pilin glycosylation and phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 49: 833–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seib KL, Jennings MP, McEwan AG. 2003. A Sco homologue plays a role in defence against oxidative stress in pathogenic Neisseria. FEBS Lett. 546: 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Serino L, Virji M. 2002. Genetic and functional analysis of the phosphorylcholine moiety of commensal Neisseria lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 43: 437–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Serino L, Virji M. 2000. Phosphorylcholine decoration of lipopolysaccharide differentiates commensal Neisseriae from pathogenic strains: identification of licA-type genes in commensal Neisseriae. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 1550–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stimson E, et al. 1996. Discovery of a novel protein modification: alpha-glycerophosphate is a substituent of meningococcal pilin. Biochem. J. 316: 29–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sung JW-C, et al. 2010. Biochemical characterizations of Escherichia coli-expressed protective antigen Ag473 of Neisseria meningitides group B. Vaccine 28: 8175–8182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Swords WE, et al. 2000. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae adhere to and invade human bronchial epithelial cells via an interaction of lipooligosaccharide with the PAF receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 37: 13–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tamayo R, Prouty AM, Gunn JS. 2005. Identification and functional analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PmrA-regulated genes. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43: 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vik A, et al. 2009. Broad spectrum O-linked protein glycosylation in the human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 4447–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weiser JN, Goldberg JB, Pan N, Wilson L, Virji M. 1998. The phosphorylcholine epitope undergoes phase variation on a 43-kilodalton protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and on pili of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 66: 4263–4267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Winther-Larsen HC, et al. 2001. Neisseria gonorrhoeae PilV, a type IV pilus-associated protein essential to human epithelial cell adherence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98: 15276–15281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zeidan Q, Hart GW. 2010. The intersections between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: implications for multiple signaling pathways. J. Cell Sci. 123: 13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.