Abstract

Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness and a major public health problem in many developing countries. It is caused by recurrent ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in childhood, with conjunctival scarring seen later in life. The pathogenesis of trachomatous scarring, however, is poorly understood, and this study was carried out to investigate the immunofibrogenic correlates of trachomatous conjunctival scarring. A case-control study of 363 cases with conjunctival scarring and 363 control participants was conducted. Investigations included in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) assessment, quantitative real-time PCR gene expression, C. trachomatis detection, and nonchlamydial bacterial culture. Trachomatous scarring was found to be strongly associated with a proinflammatory, innate immune response with increased expression of psoriasin, interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, defensin-β4A, chemokine ligand 5, and serum amyloid A1. There was also differential expression of various modifiers of the extracellular matrix, including metalloproteinases 7, 9, 10, and 12, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1, and secreted protein acidic cystein-rich-like 1. The expression of many of these genes was also significantly associated with the presence of nonchlamydial bacterial infection. These infections had a marked effect on conjunctival immune processes, including an increased inflammatory infiltrate and edema seen with IVCM. This study supports the possibility that the immunofibrogenic response in scarring trachoma is partly stimulated by nonchlamydial bacterial infection, which is characterized by the expression of innate factors.

INTRODUCTION

Trachoma is a major cause of blindness, especially in developing countries. Children suffer recurrent episodes of ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, which stimulates a follicular and papillary conjunctivitis. These children are subsequently at risk of developing conjunctival scarring, which can progress to entropion (in-turning of the eyelid) and trichiasis (eyelashes rubbing against the eyeball). Corneal opacity and blindness can result, as well as severe and persistent discomfort. Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness, with at least 1.3 million people estimated to be blind from the disease, 8.2 million to have trichiasis, and 40 million to have active disease (40, 52).

The pathogenesis of trachoma, and especially of the scarring process, is poorly understood. Histological studies of conjunctival biopsy specimens from scarred individuals show a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, especially in the substantia propria, with large numbers of lymphocytes (1, 4, 25, 51). T cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, tend to outnumber B cells. The conjunctival stroma is replaced by thick, mostly avascular scar tissue. Earlier studies examining lymphoproliferative responses to chlamydial antigens in trachomatous subjects were consistent with findings from animal models of infection, which suggested that a strong Th1 response with production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was important in clearing chlamydial infection and may be protective against the development of scarring (5, 27, 28). These studies also provided limited evidence that Th2 responses were associated with conjunctival fibrosis, which may have parallels with other infectious diseases, such as schistosomiasis (59). However, recent studies using microarray analysis of conjunctival swab samples from subjects with trachomatous trichiasis have not found evidence of Th1/Th2 polarization. Instead, proinflammatory mediators, particularly suggestive of innate immune responses and factors affecting extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, were prominent (14, 29). A number of studies have also provided compelling evidence supporting the importance of conjunctival inflammation in the development of scarring and blinding complications (11, 18, 43, 55, 57).

Two models have been proposed to account for the pathogenesis of C. trachomatis-induced scarring in the eye or genital tract: the “immunological” and the “cellular” paradigms, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive (7, 16, 53). The immunological paradigm argues that cellular immune responses, especially those involving T cells, against specific chlamydial antigens are important in causing disease. The cellular paradigm proposes that host epithelial cells act as a key innate responder cell and are central in driving tissue damage.

In this case-control study we investigated the pathophysiology of trachomatous conjunctival scarring by measuring conjunctival gene expression. We examined the hypotheses that conjunctival scarring is associated with (i) a predominantly Th2 (interleukin-13 [IL-13] mediated) rather than Th1 response, (ii) various profibrotic mediators, such as matrix metalloproteinases, and (iii) markers of innate immunity. In addition, we investigated the relationship between the expression of these various factors and both C. trachomatis and other bacterial infections. Finally, we related the gene expression profile to the microscopic tissue morphology changes and inflammatory cell infiltrate observed by in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM). IVCM is a relatively new technique to examine the ocular surface, which provides high-resolution images down to the cellular level (31, 32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the ethics committees of the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research, the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The study was explained to potential study subjects and written, informed consent was obtained before enrollment.

Participant recruitment.

The recruitment of participants into this population-based study has been previously described (30, 32). Briefly, adults with trachomatous conjunctival scarring, but without trichiasis, were recruited from an area of trachoma endemicity in the Siha district of northern Tanzania. Control subjects without scarring from the same community, frequency matched for ethnicity, were also recruited.

Clinical examination and sample collection.

All participants were examined clinically, as previously described, using the 1981 World Health Organization trachoma grading system with some modifications, including a more detailed grading for conjunctival scarring (17, 30, 32). The left conjunctiva was anesthetized with preservative-free proxymetacaine 0.5% eye drops (Minims; Chauvin Pharmaceuticals) and a swab collected for microbiological analysis from the inferior fornix. Two upper tarsal conjunctival swabs were also collected (Dacron polyester-tipped; Hardwood Products Company, Guildford, ME). The first was for RNA isolation (described later) and was placed directly into a tube containing 0.2 ml of RNA stabilizer (RNAlater; Life Technologies, United Kingdom). The second was for C. trachomatis detection and put into a dry tube. Samples were kept on ice packs until frozen later the same day at −80°C.

Confocal microscopy assessment.

IVCM examination of the upper tarsal conjunctiva was performed using a Heidelberg Retina Tomograph 3 (HRT3) in combination with the Rostock Corneal Module (RCM) (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Dossenheim, Germany) according to previously described examination and image grading protocols (31). IVCM images were graded for inflammatory features and subepithelial connective tissue organization/scarring (Fig. 1 and 2).

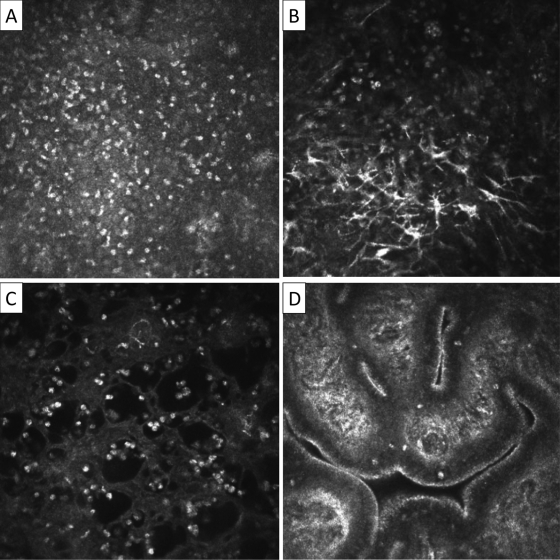

Fig 1.

In vivo confocal microscopy grading system of inflammatory features. Images are 400 by 400 μm. (A) Inflammatory infiltrate: seen as multiple bright white nuclei. The mean inflammatory cell density of three randomly selected volume scans is calculated using the HRT/RCM software. The individual scan with the highest density of cells from within the volume scan is used for inflammatory cell density counting. (B) Dendritiform cells: graded as present or absent. To be present, the mean number of DCs per volume scan needs to be ≥1. The largest number of dendritiform cells in any individual scan in a volume scan is used for measurement. A mean number of ≥1 is used to differentiate occasional dendritiform cells seen in scans of otherwise normal subjects. (C) Tissue edema: seen as multiple black empty spaces. Graded as present or absent in any volume scan. (D) Papillae: seen as elevations with a central vascular network. Graded as present or absent in any volume scan.

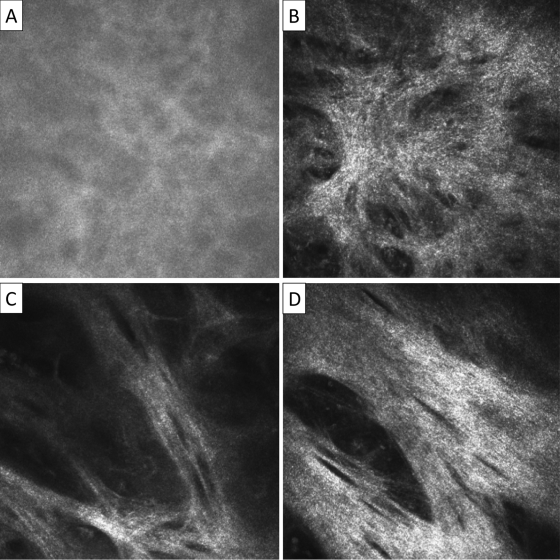

Fig 2.

In vivo confocal microscopy grading system for conjunctival connective tissue organization. Images are 400 by 400 μm. (A) Normal: homogenous, amorphous appearance, with occasional, fine, wispy strands. (B) Grade 1: heterogenous appearance with poorly defined clumps or bands present. (C) Grade 2: clearly defined bands of tissue which constitute less than 50% of the area of the scan. (D) Grade 3: clearly defined bands or sheets of tissue which constitute 50% or more of the area of the scan and in which striations are present. If different grades of scarring are seen within a particular volume scan then the highest grade is recorded. The connective tissue which is graded needs to be separate from that associated with the vascular tissue; if this is not possible then the scan is considered ungradable.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Twenty-three different human gene transcripts were selected for quantitation by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), including the following: IFN-γ (IFNG); indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (INDO); tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA); interleukin-1β (IL1B); interleukin-10 (IL-10); interleukin-12β (IL12B); interleukin 13 (IL-13); interleukin-13 receptor, alpha 2 (IL13RA2); S100 calcium-binding protein A7 (S100A7); defensin, beta 4A (DEFB4A); chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 (CXCL5); serum amyloid A1 (SAA1); arginase, liver (ARG1); nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible (NOS2); matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1); matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7); matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9); matrix metalloproteinase 10 (MMP10); matrix metalloproteinase 12 (MMP12); TIMP (tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase) matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1); SPARC (secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich)-like 1 (hevin) (SPARCL1); complement factor H (CFH); and CD83 molecule (CD83).

Genes were chosen to investigate the specific hypotheses outlined above. Specifically, IFNG, IL12B, IL-13, and IL13RA2 expression was used to investigate a Th1/Th2 predominance; the expression of matrix metalloproteinases, TIMP1, and SPARCL1 as potentially important regulators of extracellular matrix; and IL1B, TNFA, S100A7, DEFB4A, CXCL5, and SAA1 expression as evidence of a proinflammatory and/or innate immune response. We were also interested in examining evidence of differential macrophage activity (ARG1 and NOS2), mature dendritic cells (CD83), and complement regulation (CFH). The selection of these genes was informed by previous studies, including a conjunctival microarray transcriptome analysis (6, 9, 14, 15, 22, 27, 28, 42, 46, 47–49). The microarray data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers GSE23705 (Ethiopia) and GSE24383 (Tanzania).

Total RNA was extracted from the swab sample using an RNeasy microkit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Multiplex real-time quantitative PCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Cambridge, United Kingdom) using the QuantiTect Multiplex NoROX kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Probes and primers for multiplex assays, which included up to four separate targets (including HPRT-1, which was used as a reference gene), were designed and synthesized by Sigma Life Science (www.sigma.com/designmyprobe; available on request). The samples were tested in duplicate, in a total reaction mixture volume of 25 μl, which contained 2 μl of sample or standard. The thermal cycle protocol used the following conditions: 95°C for 15 min, followed by 45 to 50 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s and then annealing and extension at 60°C for 30 s. Fluorescence data was acquired at the end of each cycle. The relative efficiency of the component reactions was assessed using standards containing all targets in a sequence of 10-fold serial dilutions.

Microbiology samples and analysis.

C. trachomatis DNA was detected using a PCR-based assay (Amplicor CT/NG Test; Roche) with previously described modifications (12). Samples for culture were inoculated onto blood and chocolate agar later on the day of collection (rarely more than 6 h) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Culture isolates were identified by standard microbiological techniques.

Data analysis.

Data were entered into Access 2007 (Microsoft) and analyzed using STATA 11.0 (StataCorp LP, TX). The transcript abundances for the genes of interest were standardized relative to that of HPRT1 in the same reaction mixture using the ΔΔCT method and were normalized by log10 transformation (37). Linear regression models were used to estimate the fold changes (age and sex adjusted) in the levels of gene expression in those with clinically visible scarring compared to controls, subdivided into those with no/minimal inflammation (TS [inflammation grades P0 and P1]) and those with inflammation (TSI [inflammation grades P2 and P3]), where P0 is no inflammation, P1 is minimal inflammation with individual papillae prominent, P2 is moderate inflammation in which normal vessels appear hazy, and P3 is pronounced inflammation in which normal vessels on the tarsus are hidden over more than half the surface) (17). Similar fold changes were estimated for the presence of clinically significant inflammation (P2 or P3), adjusted for the level of clinical scarring as well as age and sex. Age- and sex-adjusted fold changes in gene expression by grade of IVCM connective tissue organization/scarring and for the presence of dendritiform cells were also estimated. Correlation coefficients were estimated between the increase in gene expression (log10 transformed) and the IVCM inflammatory infiltrate, with the significance tested using age- and sex-adjusted linear regression models. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess the strength of association of each factor with the gene expression fold change. P values for all associations are shown in Results. For reference, the P values for the critical significance thresholds determined by a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons are shown in the table footnotes. However, the choice of targets for gene expression was not selected at random, as is assumed by the Bonferroni method, but contain related groups of genes which might be expected to act in a similar manner. In addition, using such a conservative correction increases the likelihood of a type 2 error.

RESULTS

Study participants.

We recruited 363 cases with trachomatous conjunctival scarring and 363 control participants without scarring. The demographic, clinical, IVCM, and nonchlamydial bacterial infection data have previously been reported in detail (30, 32). In summary, controls were younger than the cases (mean 31.9 versus 50.3 years, P < 0.001), and all analyses were age and sex adjusted. Conjunctival scarring in the cases was mostly mild to moderate and cases had significantly more clinical inflammation than controls. IVCM analysis showed that the cases had more inflammatory cells and a higher connective tissue scarring score. Nonchlamydial pathogenic organisms were cultured more frequently from cases (25 [6.9%]) than from controls (7 [1.9%], P = 0.002). The most frequently cultured pathogenic organisms were Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae, while coagulase-negative staphylococci, Corynebacterium spp., Streptococcus viridans, and Bacillus spp. were designated as commensal organisms in this analysis. Five (1.4%) of the cases and none of the controls had C. trachomatis infection detected.

Conjunctival gene expression.

Quantitative, real-time RT-PCR was performed for 23 gene expression targets for all 363 cases and 363 controls. There was inadequate sample for detection in four samples (three cases and one control), and amplification failed in a number of experiments for technical reasons related to laboratory power supply problems. The number of samples successfully detected for each target ranged from 313 to 359 for cases and 316 to 362 for controls.

Gene expression levels in relation to clinical findings.

Cases with scarring had enriched gene expression compared to controls for the majority of transcripts measured, even after adjusting for age and sex (Table 1). This tended to be more marked in those cases with inflammation (increased: INDO, TNFA, IL1B, S100A7, DEFB4A, CXCL5, SAA1, ARG, NOS2, MMP7, MMP9, MMP12, TIMP1, and CD83; decreased: MMP10, CFH, and SPARCL1). There was also some evidence, but with less robust P values, that the expression of IFNG and IL13RA2 were increased in cases with scarring.

Table 1.

Conjunctival gene expression in relation to clinical phenotypea

| Geneb | TSI vs C |

TS vs C |

Inflamed vs noninflamed |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | P | FC | P | FC | P | |

| S100A7 | 5.54 | <0.0001 | 3.2 | <0.0001 | 1.3 | 0.11 |

| SAA1 | 4.99 | <0.0001 | 2.11 | <0.0001 | 1.6 | 0.04 |

| DEFB4A | 4.72 | <0.0001 | 1.42 | 0.01 | 2.46 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL5 | 3.89 | <0.0001 | 1.18 | 0.43 | 3.4 | <0.0001 |

| MMP12 | 3.55 | <0.0001 | 1.74 | <0.0001 | 1.62 | 0.0002 |

| INDO | 3.29 | <0.0001 | 1.5 | <0.0001 | 1.96 | <0.0001 |

| MMP9 | 3.06 | <0.0001 | 1.76 | <0.0001 | 1.67 | <0.0001 |

| IL1B | 2.57 | <0.0001 | 1.59 | <0.0001 | 1.48 | 0.0003 |

| NOS2 | 2.16 | <0.0001 | 1.27 | 0.005 | 1.38 | 0.007 |

| MMP7 | 2.14 | <0.0001 | 1.23 | 0.003 | 1.51 | <0.0001 |

| CD83 | 1.9 | <0.0001 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 1.31 | 0.0004 |

| IL13RA2 | 1.62 | 0.006 | 1.38 | 0.008 | 1.08 | 0.65 |

| IL12B | 1.52 | 0.02 | 1.29 | 0.04 | 1.22 | 0.23 |

| TNFA | 1.47 | <0.0001 | 1.14 | 0.008 | 1.23 | 0.003 |

| IL-10 | 1.46 | 0.2 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 1.27 | 0.42 |

| TIMP1 | 1.46 | <0.0001 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 0.93 | 0.3 |

| IFNG | 1.42 | 0.001 | 1.06 | 0.4 | 1.41 | 0.002 |

| ARG1 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 1.25 | 0.0003 | 1.04 | 0.64 |

| IL-13 | 1.22 | 0.3 | 1.17 | 0.19 | 1.09 | 0.64 |

| CFH | 0.75 | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 0.005 | 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| MMP1 | 0.58 | 0.009 | 1.28 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.02 |

| MMP10 | 0.38 | <0.0001 | 0.86 | 0.02 | 0.54 | <0.0001 |

| SPARCL1 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.51 | <0.0001 | 0.19 | <0.0001 |

TSI versus C and TS versus C values were adjusted for age and sex. Inflamed versus noninflamed values were adjusted for age, sex, and level of clinical scarring. Using a Bonferroni correction for 69 comparisons, a P value of <0.0007 would be considered significant. See the text for discussion. TSI, trachomatous scarring with inflammation; TS, trachomatous scarring without inflammation; FC, fold change.

S100A7 = S100 calcium binding protein A7; SAA1 = serum amyloid A1; DEFB4A = defensin, beta 4A; CXCL5 = chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5; MMP12 = matrix metalloproteinase 12; INDO = indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase; MMP9 = matrix metalloproteinase 9; IL1B = interleukin-1; NOS2 = nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible; MMP7 = matrix metalloproteinase 7; CD83 = CD83 molecule; IL13RA2 = interleukin 13 receptor, alpha 2; IL12B = interleukin-12β; TNFA = tumor necrosis factor, alpha/beta; IL-10 = interleukin 10; TIMP1 = TIMP (tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase) matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor 1; IFNG = interferon gamma; ARG1 = arginase, liver; IL-13 = interleukin-13; CFH = complement factor H; MMP1 = matrix metalloproteinase 1; MMP10 = matrix metalloproteinase 10; SPARCL1 = SPARC (secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich)-like 1 (hevin).

After adjusting for age, sex, and the level of clinical scarring, a number of genes were also differentially expressed in those with clinical inflammation compared to those without inflammation (increased: INDO, IL1B, DEFB4A, CXCL5, MMP7, MMP9, MMP12, and CD83; decreased: MMP10, SPARCL1, and CFH).

Gene expression in relation to IVCM findings.

The relationships between the gene expression results and the IVCM findings are presented in Table 2. Increasing IVCM connective tissue grade was associated with increased expression of S100A7 (which also had the largest fold changes), TIMP1, and CFH and with decreased expression of SPARCL1. There was also some evidence, but with less-robust P values, that the connective tissue grade was associated with increased levels of INDO, IL1B, SAA1, ARG1, MMP12, and CD83.

Table 2.

Gene expression levels in relation to in vivo confocal microscopy findingsa

| Gene | FC in gene expression with increasing connective tissue grade |

IVCM infiltrate |

FC in gene expression if dendritiform cells are present |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | FC | P | CC | P | FC | P | |

| S100A7 | 1 | 1.00 | <0.0001 | 0.43 | <0.0001 | 2.03 | 0.0004 |

| 2 | 1.64 | ||||||

| 3 | 3.76 | ||||||

| SAA1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.002 | 0.28 | <0.0001 | 1.80 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 1.18 | ||||||

| 3 | 2.74 | ||||||

| DEFB4A | 1 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.42 | <0.0001 | 1.74 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.84 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.60 | ||||||

| CXCL5 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 1.51 | 0.22 |

| 2 | 1.25 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.40 | ||||||

| MMP12 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.004 | 0.31 | <0.0001 | 1.36 | 0.05 |

| 2 | 1.23 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.69 | ||||||

| INDO | 1 | 1.00 | 0.004 | 0.16 | <0.0001 | 1.71 | 0.0001 |

| 2 | 1.17 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.60 | ||||||

| MMP9 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.28 | <0.0001 | 1.19 | 0.19 |

| 2 | 1.26 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.33 | ||||||

| IL1B | 1 | 1.00 | 0.008 | 0.49 | <0.0001 | 1.15 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 1.18 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.45 | ||||||

| NOS2 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 1.28 | 0.07 |

| 2 | 1.01 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.33 | ||||||

| MMP7 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 1.06 | 0.62 |

| 2 | 1.02 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.12 | ||||||

| CD83 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.003 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 1.21 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.13 | ||||||

| IL13RA2 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.14 | 0.005 | 0.92 | 0.65 |

| 2 | 0.98 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.11 | ||||||

| IL12B | 1 | 1.00 | 0.87 | –0.09 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.59 |

| 2 | 1.06 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.07 | ||||||

| TNFA | 1 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.009 | 1.05 | 0.54 |

| 2 | 1.07 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.04 | ||||||

| IL-10 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.0003 | 1.11 | 0.77 |

| 2 | 0.86 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.49 | ||||||

| TIMP1 | 1 | 1.00 | <0.0001 | 0.19 | 0.0005 | 1.09 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 1.18 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.46 | ||||||

| IFNG | 1 | 1.00 | 0.43 | –0.12 | 0.0003 | 1.05 | 0.71 |

| 2 | 0.91 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.89 | ||||||

| ARG | 1 | 1.00 | 0.003 | 0.14 | 0.002 | 1.09 | 0.42 |

| 2 | 1.24 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.17 | ||||||

| IL-13 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.001 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 1.24 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.94 | ||||||

| CFH | 1 | 1.00 | 0.0004 | –0.09 | 0.004 | 0.93 | 0.30 |

| 2 | 1.15 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.24 | ||||||

| MMP1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.87 |

| 2 | 1.06 | ||||||

| 3 | 1.40 | ||||||

| MMP10 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.02 | –0.22 | <0.0001 | 0.76 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 1.14 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.85 | ||||||

| SPARCL1 | 1 | 1.00 | <0.0001 | –0.27 | <0.0001 | 0.30 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 0.87 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.67 | ||||||

Fold change (FC) values were adjusted for age and sex. Using a Bonferroni correction for 69 comparisons, a P value of <0.0007 would be considered significant. See the text for further discussion. IVCM, in vivo confocal microscopy; CC, correlation coefficient. See Table 1 for gene abbreviations.

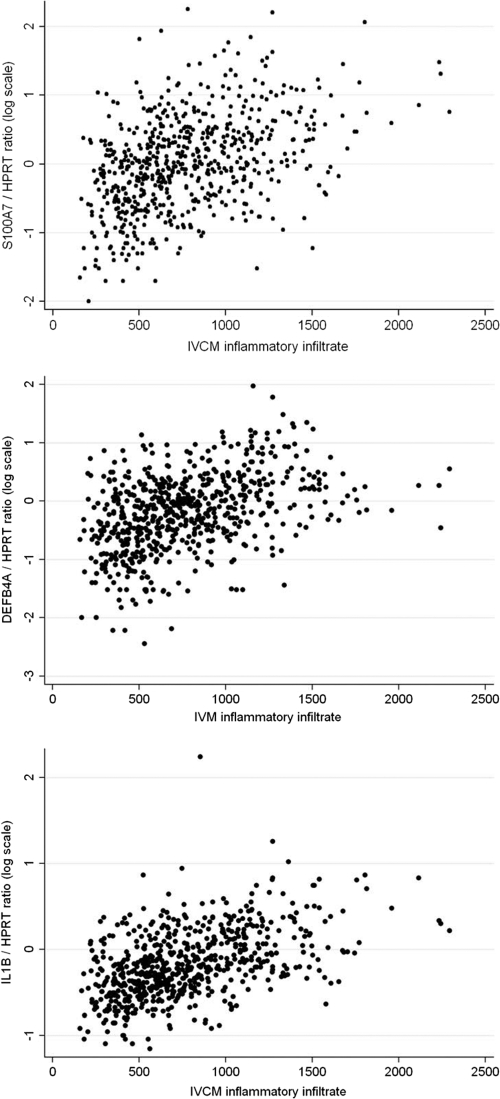

The expression of a number of genes was correlated with the IVCM inflammatory infiltrate density. The correlation coefficient for IL1B, S100A7, and DEFB4 was greater than +0.40 (Fig. 3). For SAA1, MMP9, and MMP12 it was between +0.25 and +0.35, and for MMP10 and SPARCL1 it was between −0.20 and −0.30. The presence of DFCs was associated with increased expression of INDO and S100A7 and with decreased expression of SPARCL1.

Fig 3.

Gene expression levels relative to HPRT1 of S100A7, DEFB4A, and IL1B by in vivo confocal microscopy inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Gene expression levels in relation to microbiology findings.

Infection with C. trachomatis was associated with upregulated IFNG, INDO, and NOS2 and with downregulated MMP10 and SPARCL1 (Table 3; note that only five participants had detectable C. trachomatis DNA). There was also some evidence, but with less-robust P values, that C. trachomatis infection was associated with increased IL12B, MMP1, MMP7, and MMP10. Nonchlamydial bacterial infection was associated with increased expression of INDO, S100A7, DEFB4A, and MMP12 and with decreased expression of MMP10, SPARCL1, and CFH (Table 3). There was also some evidence that nonchlamydial bacterial infection was associated with increased IL1B, IL-10, CXCL5, SAA1, MMP7, and MMP9.

Table 3.

Gene expression in relation to microbiological infection statusa

| Gene | Chlamydial infection |

Nonchlamydial bacterial infection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | P | FCb | P | |

| S100A7 | 4.21 | 0.04 | 2.59 | 0.0006 |

| SAA1 | 8.06 | 0.01 | 2.47 | 0.008 |

| DEFB4A | 4.82 | 0.02 | 3.56 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL5 | 8.2 | 0.07 | 4.15 | 0.002 |

| MMP12 | 1.84 | 0.21 | 2.21 | <0.0001 |

| INDO | 6.78 | <0.0001 | 2.74 | <0.0001 |

| MMP9 | 1.57 | 0.28 | 1.73 | 0.002 |

| IL1B | 1.49 | 0.32 | 1.72 | 0.001 |

| NOS2 | 4.5 | 0.0003 | 1.40 | 0.06 |

| MMP7 | 3.01 | 0.002 | 1.52 | 0.003 |

| CD83 | 1.30 | 0.34 | 1.27 | 0.05 |

| IL13RA2 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.94 |

| IL12B | 3.10 | 0.05 | 1.16 | 0.56 |

| TNFA | 1.60 | 0.06 | 1.14 | 0.20 |

| IL-10 | 1.29 | 0.81 | 3.30 | 0.005 |

| TIMP1 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.09 | 0.36 |

| IFNG | 4.2 | <0.0001 | 1.12 | 0.46 |

| ARG | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.56 |

| IL-13 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.13 |

| CFH | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.67 | <0.0001 |

| MMP1 | 0.14 | 0.004 | 0.59 | 0.06 |

| MMP10 | 0.34 | 0.002 | 0.46 | <0.0001 |

| SPARCL1 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.09 | <0.0001 |

Fold change (FC) values were adjusted for age and sex. Using a Bonferroni correction for 46 comparisons, a P value of <0.001 would be considered significant. See the text for further discussion. See Table 1 for gene abbreviations.

Compared to no organism cultured.

IVCM findings in relation to nonchlamydial bacterial infection status.

A new combined analysis of previously published IVCM and microbiology data found that pathogenic organisms were associated with significantly more inflammatory cells (P < 0.0006) and with the presence of tissue edema (P = 0.02) (Table 4) (30, 32).

Table 4.

In vivo confocal microscopy parameters by nonchlamydial bacterial infection statusa

| IVCM parameter | No organism |

Pathogenic organism |

Adjusted increaseb | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |||

| Inflammatory infiltrate (no. of cells/mm2) | 731 | 694–769 | 972 | (841–1102) | 230 | 0.0006 |

| Connective tissue organization score | 1.04 | 0.97–1.11 | 1.31 | (1.06–1.56) | 0.12 | 0.40 |

| No. | % | No. | % | Adjusted ORb | ||

| Dendritiform cells present | 22 | (6.0) | 4 | (14.3) | 1.89 | 0.33 |

| Tissue edema present | 13 | (3.6) | 3 | (10.7) | 5.4 | 0.02 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Compared to no growth and adjusted for age and sex.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have used gene expression measurement of conjunctival swab samples to study the pathogenesis of trachoma (6, 9, 14, 21, 22, 29, 46). However, this is the first study to systematically compare a large number of cases with trachomatous scarring and control subjects in which the scarring had not yet progressed to trichiasis. Cases with trichiasis are quite distinct from cases with scarring alone since they have a persistent foreign body abrading the globe stimulating inflammation and facilitating secondary infection (13). In the present study we have shown that scarring without trichiasis is associated with large fold changes in gene expression of various cytokines, chemokines, and other immunofibrogenic mediators, even though the scarring was generally mild to moderate.

We found that mild to moderate trachomatous scarring is strongly associated with a proinflammatory, innate immune response, which has marked antimicrobial properties, with increased expression of S100A7, DEFB4A, CXCL5, IL1B, TNFA, and SAA1. This is consistent with a transcriptome microarray study of end-stage scarring trachoma with trichiasis from Ethiopia (14). In both studies the expression of S100A7 (psoriasin) showed the greatest fold increase between cases and controls. Psoriasin was initially identified as being upregulated in epithelial cells from psoriatic lesions (38). It is an antimicrobial peptide (AMP) and therefore an important component of innate immune defense (56). Psoriasin is chemotactic for neutrophils and regulates neutrophil function by inducing the production of several cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (34, 61). It has been shown to reduce Escherichia coli survival, the mechanism of which may be either through zinc sequestration or direct adherence with the bacteria (24, 36). It has more recently been shown to be upregulated at the ocular surface in response to Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae (23). Binding of E. coli flagellin by the Toll-like receptor 5 on keratinocytes is important in psoriasin induction, supporting its role as an innate immune molecule (2). The defensins are another group of AMPs found at the ocular surface, with β-defensins released by leukocytes and epithelial cells (26, 41). CXCL5 is a potent chemotaxin involved in neutrophil activation which is produced by epithelial cells (33, 56). Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1β are proinflammatory mediators which play a central role in mediating an innate immune response and have previously been found to be associated with active and scarring trachoma (3, 6, 9, 15, 22, 47). Serum amyloid A, of which SAA1 is a main isoform, is an acute-phase protein which is raised in inflammatory diseases and has been shown to have antibacterial effects (19, 39).

The upregulation of these various proinflammatory, chemotactic, and antimicrobial mediators suggests an important role for the innate immune response in trachomatous scarring. This is consistent with the cellular paradigm of Chlamydia trachomatis pathogenesis. While there was some evidence of Th1 response in scarring (increased IFNG and INDO expression), there was no significant difference in IL-13 expression, which might have suggested a Th2 response. There was some evidence that the expression of IL13RA2, which appears to act as a decoy receptor for IL-13 and opposes its function, was increased in cases compared to controls (60).

Many of the measured transcripts were upregulated in the presence of clinical inflammation. When scarred cases were compared to controls without scarring, the additional presence of inflammation in the cases tended to lead to more marked increases in gene expression. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that episodes of inflammation are important in the pathogenesis of scarring and blindness. It is also interesting that a number of genes, for example, S100A7, IL1B, SAA1, and MMP12, showed large fold changes in gene expression even in relatively noninflamed cases with scarring compared to controls. These genes also showed a clearly progressive increase in expression with increasing IVCM connective tissue organization grade.

We found infection with C. trachomatis to be infrequent in these adults with conjunctival scarring, with a similar detection rate to previous studies of trachomatous trichiasis (8, 11, 13). While caution is needed in interpreting these data because of the small numbers, individuals infected with C. trachomatis had gene expression profiles characteristic of C. trachomatis infection in children (9, 46). There was a typical Th1-dominated response, with upregulated IFNG and IL12B (P = 0.05) and also INDO and NOS2 (both IFN-γ regulated) and some acute-phase reactants. Infection with other bacteria was more frequent, and many of the genes described above involved in innate immunity showed moderate to large increases in expression if a pathogenic organism was present. A previous study found that the presence of bacterial infection was associated with increased expression of IL1B, TNF-α, MMP1, MMP9, and TIMP2 after trichiasis surgery (10). In the present study, bacterial infection was also found to be associated with an increased inflammatory infiltrate and tissue edema with IVCM. Overall, these studies support the hypothesis that nonchlamydial bacterial infection is important in driving the scarring process.

Matrix metalloproteinases are capable of degrading the protein components of the ECM and also have wide-ranging effects on inflammatory and immune responses (50, 58). Previous studies have implicated MMPs in the pathogenesis of trachomatous scarring, and this was further confirmed in the present study in a separate population (9, 10, 14, 20, 29, 44). MMP7, MMP9, MMP12, and TIMP1 were upregulated in scarring and inflammation, whereas MMP10 and SPARCL1 were downregulated. SPARCL1 is a matricellular protein, which regulates the synthesis and turnover of the ECM (35, 54). The gene expression levels by clinical scarring grade were broadly consistent with the levels by IVCM connective tissue grade, and the expression levels by clinical inflammation were consistent with the IVCM inflammatory infiltrate correlation. The differential gene expression of these ECM modifiers was closely related to bacterial infection status as discussed above.

Strengths of this population-based study were that we studied a large number of cases with early scarring trachoma to analyze gene expression changes in relation to the clinical, IVCM, and microbiological status. There are, however, a number of limitations. Gene expression levels do not necessarily reflect the level of functional protein, exemplified by transforming growth factor β, which has significant posttranscriptional regulation. Conjunctival swabs obtain material from the tissue surface and so have a tendency to limit the observations to events in or near the epithelium. To address these two issues, we are currently comparing gene expression with immunohistochemical analysis of conjunctival biopsy tissue.

This study showed that mild to moderate trachomatous scarring is strongly associated with a proinflammatory, innate immune response and with differential expression of various modifiers of the ECM. We found no evidence for an active role for IL-13/Th2 responses at this stage of the disease. This is consistent with the findings from a microarray transcriptome study from Ethiopia on advanced trachomatous scarring (14). We were also able to use IVCM to show differential transcript levels according to connective tissue morphology and inflammatory cell infiltrate. A key determinant in the expression of many of these genes appears to be the presence of nonchlamydial bacterial infection which, as well as causing inflammation, may contribute to the scarring process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the participants for their involvement.

This study was funded by a fellowship grant to M.J.B. from the Wellcome Trust (080741/Z/06/Z). V.H.H. is supported by a fellowship grant from the British Council for the Prevention of Blindness (Barrie Jones Fellowship). The funders had no part in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 October 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Abrahams C, Ballard RC, Sutter EE. 1979. The pathology of trachoma in a black South African population: light microscopical, histochemical, and electron microscopical findings. S. Afr. Med. J. 55: 1115–1118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abtin A, et al. 2008. Flagellin is the principal inducer of the antimicrobial peptide S100A7c (psoriasin) in human epidermal keratinocytes exposed to Escherichia coli. FASEB J. 22: 2168–2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abu el-Asrar AM, et al. 1998. Immunopathogenesis of conjunctival scarring in trachoma. Eye 12(Pt 3a): 453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. al-Rajhi AA, Hidayat A, Nasr A, al-Faran M. 1993. The histopathology and the mechanism of entropion in patients with trachoma. Ophthalmology 100: 1293–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bailey RL, Holland MJ, Whittle HC, Mabey DC. 1995. Subjects recovering from human ocular chlamydial infection have enhanced lymphoproliferative responses to chlamydial antigens compared with those of persistently diseased controls. Infect. Immun. 63: 389–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bobo L, et al. 1996. Evidence for a predominant proinflammatory conjunctival cytokine response in individuals with trachoma. Infect. Immun. 64: 3273–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brunham RC, Rey-Ladino J. 2005. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5: 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burton MJ, et al. 2007. Bacterial infection and trachoma in the Gambia: a case control study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48: 4440–4444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burton MJ, Bailey RL, Jeffries D, Mabey DC, Holland MJ. 2004. Cytokine and fibrogenic gene expression in the conjunctivas of subjects from a Gambian community where trachoma is endemic. Infect. Immun. 72: 7352–7356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burton MJ, et al. 2010. Conjunctival expression of matrix metalloproteinase and proinflammatory cytokine genes after trichiasis surgery. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51: 3583–3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burton MJ, et al. 2006. The long-term natural history of trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47: 847–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burton MJ, et al. 2003. Which members of a community need antibiotics to control trachoma? Conjunctival Chlamydia trachomatis infection load in Gambian villages. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44: 4215–4222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burton MJ, et al. 2005. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin following surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 89: 1282–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burton MJ, et al. 2011. Conjunctival transcriptome in scarring trachoma. Infect. Immun. 79: 499–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Conway DJ, et al. 1997. Scarring trachoma is associated with polymorphism in the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) gene promoter and with elevated TNF-alpha levels in tear fluid. Infect. Immun. 65: 1003–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Darville T, Hiltke TJ. 2010. Pathogenesis of genital tract disease due to Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Infect. Dis. 201(Suppl 2): S114–S125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dawson CR, Jones BR, Tarizzo ML. 1981. Guide to trachoma control. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dawson CR, Daghfous MRR, Juster R, Schachter J. 1990. What clinical signs are critical in evaluating the impact of intervention in trachoma?, p. 271–275 In Chlamydia infections. Proc. 7th Int. Symp. Human Chlamydial Infect. Cambridge University Press, London, England [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eckhardt ER, et al. Intestinal epithelial serum amyloid A modulates bacterial growth in vitro and proinflammatory responses in mouse experimental colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 10: 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. El-Asrar AM, et al. 2000. Expression of gelatinase B in trachomatous conjunctivitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 84: 85–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Faal N, et al. 2006. Conjunctival FOXP3 expression in trachoma: do regulatory T cells have a role in human ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection? PLoS Med. 3: e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Faal N, et al. 2005. Temporal cytokine gene expression patterns in subjects with trachoma identify distinct conjunctival responses associated with infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 142: 347–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garreis F, et al. 2011. Expression and regulation of antimicrobial peptide psoriasin (S100A7) at the ocular surface and in the lacrimal apparatus. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52: 4914–4922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glaser R, et al. 2005. Antimicrobial psoriasin (S100A7) protects human skin from Escherichia coli infection. Nat. Immunol. 6: 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guzey M, et al. 2000. A survey of trachoma: the histopathology and the mechanism of progressive cicatrization of eyelid tissues. Ophthalmologica 214: 277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hazlett L, Wu M. 2011. Defensins in innate immunity. Cell Tissue Res. 343: 175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holland MJ, et al. 1996. T helper type-1 (Th1)/Th2 profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC); responses to antigens of Chlamydia trachomatis in subjects with severe trachomatous scarring. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 105: 429–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holland MJ, Bailey RL, Hayes LJ, Whittle HC, Mabey DC. 1993. Conjunctival scarring in trachoma is associated with depressed cell-mediated immune responses to chlamydial antigens. J. Infect. Dis. 168: 1528–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holland MJ, et al. 2010. Pathway-focused arrays reveal increased matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin) transcription in trachomatous trichiasis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51: 3893–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu VH, et al. 2011. Bacterial infection in scarring trachoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52: 2181–2186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hu VH, et al. 2011. In vivo confocal microscopy of trachoma in relation to normal tarsal conjunctiva. Ophthalmology 118: 747–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu VH, et al. 2011. In vivo confocal microscopy in scarring trachoma. Ophthalmology 118: 2138–2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeyaseelan S, et al. 2005. Induction of CXCL5 during inflammation in the rodent lung involves activation of alveolar epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32: 531–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jinquan T, et al. 1996. Psoriasin: a novel chemotactic protein. J. Invest. Dermatol. 107: 5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kang MH, Oh DJ, Rhee DJ. 2011. Effect of hevin deletion in mice and characterization in trabecular meshwork. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52: 2187–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee KC, Eckert RL. 2007. S100A7 (psoriasin): mechanism of antibacterial action in wounds. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127: 945–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Madsen P, et al. 1991. Molecular cloning, occurrence, and expression of a novel partially secreted protein “psoriasin” that is highly up-regulated in psoriatic skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 97: 701–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Malle E, Sodin-Semrl S, Kovacevic A. 2009. Serum amyloid A: an acute-phase protein involved in tumour pathogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66: 9–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mariotti SP, Pascolini D, Rose-Nussbaumer J. 2009. Trachoma: global magnitude of a preventable cause of blindness. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 93: 563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McDermott AM. 2009. The role of antimicrobial peptides at the ocular surface. Ophthalmic Res. 41: 60–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mozzato-Chamay N, et al. 2000. Polymorphisms in candidate genes and risk of scarring trachoma in a Chlamydia trachomatis–endemic population. J. Infect. Dis. 182: 1545–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Munoz B, et al. 1999. Incidence of trichiasis in a cohort of women with or without scarring. Int. J. Epidemiol. 28: 1167–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Natividad A, et al. 2006. A coding polymorphism in matrix metalloproteinase 9 reduces risk of scarring sequelae of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection. BMC Med. Genet. 7: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reference deleted.

- 46. Natividad A, et al. 2010. Human conjunctival transcriptome analysis reveals the prominence of innate defense in Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect. Immun. 78: 4895–4911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Natividad A, et al. 2007. Genetic variation at the TNF locus and the risk of severe sequelae of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Gambians. Genes Immun. 8: 288–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Natividad A, et al. 2008. Susceptibility to sequelae of human ocular chlamydial infection associated with allelic variation in IL10 cis-regulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Natividad A, et al. 2005. Risk of trachomatous scarring and trichiasis in Gambians varies with SNP haplotypes at the interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 loci. Genes Immun. 6: 332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. 2004. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4: 617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reacher MH, Pe'er J, Rapoza PA, Whittum-Hudson JA, Taylor HR. 1991. T cells and trachoma: their role in cicatricial disease. Ophthalmology 98: 334–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Resnikoff S, et al. 2004. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull. World Health Organ. 82: 844–851 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stephens RS. 2003. The cellular paradigm of chlamydial pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 11: 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sullivan MM, et al. 2006. Matricellular hevin regulates decorin production and collagen assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 27621–27632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. West SK, Munoz B, Mkocha H, Hsieh YH, Lynch MC. 2001. Progression of active trachoma to scarring in a cohort of Tanzanian children. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 8: 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wiesner J, Vilcinskas A. 2010. Antimicrobial peptides: the ancient arm of the human immune system. Virulence 1: 440–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wolle MA, Munoz BE, Mkocha H, West SK. 2009. Constant ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis predicts risk of scarring in children in Tanzania. Ophthalmology 116: 243–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wynn TA. 2008. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J. Pathol. 214: 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wynn TA. 2004. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4: 583–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wynn TA. 2003. IL-13 effector functions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21: 425–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zheng Y, et al. 2008. Microbicidal protein psoriasin is a multifunctional modulator of neutrophil activation. Immunology 124: 357–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]