Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) likely originated by acquisition of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) from coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS). However, it is unknown whether the same SCCmec types are present in MRSA and CNS that reside in the same niche. Here we describe a study to determine the presence of a potential mecA reservoir among CNS recovered from 10 pig farms. The 44 strains belonged to 10 different Staphylococcus species. All S. aureus strains belonged to sequence type 398 (ST398), with SCCmec types V and IVa. Type IVc, as well as types III and VI, novel subtypes of type IV, and not-typeable types, were found in CNS. S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and S. haemolyticus shared SCCmec type V. The presence of SCCmec type IVc in several staphylococcal species isolated from one pig farm is noteworthy, suggesting exchange of this SCCmec type in CNS, but the general distribution of this SCCmec type still has to be established. In conclusion, this study shows that SCCmec types among staphylococcal species on pig farms are heterogeneous. On two farms, more than one recovered staphylococcal species harbored the same SCCmec type. We conclude that staphylococci on pig farms act as a reservoir of heterogeneous SCCmec elements. These staphylococci may act as a source for transfer of SCCmec to S. aureus.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), an important pathogen in humans and animals, is responsible for considerable mortality, morbidity, and health care expenditure in both hospitals and the community (29). Methicillin resistance is associated with the presence of the mecA gene, which encodes an additional penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a or PBP2′). This protein has a lower affinity for all beta-lactam antibiotics (12). The mecA gene is located on a mobile genetic element called staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) (14).

The origin of SCCmec remains unknown, but it is believed that the mecA gene itself originated with one common precursor. Homologues of a mecA gene have been found in Staphylococcus sciuri (5) and Staphylococcus vitulinus (22). However, these mecA gene homologues are not located in a mecA complex as with SCCmec. Tsubakishita et al. (24) showed that a mecA gene homologue present in Staphylococcus fleurettii showed 99 to 100% sequence homology with the mecA gene present in MRSA strain N315. Additional sequence analysis showed the presence of an almost identical structure of the mecA complex. This result indicates that a direct precursor of the methicillin resistance determinant for MRSA is present in S. fleurettii, which is a member of the S. sciuri group within the staphylococci (24). S. fleurettii is a commensal bacterium of animals, and having the ancestor of the mecA gene present in an animal-borne staphylococcal species suggests that SCCmec elements may be generated in a Staphylococcus species that has an animal as its normal host. The possibility that mecA may have originated with S. fleurettii strengthens the hypothesis that MRSA probably acquired SCCmec from coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) (11). This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that methicillin resistance among human clinical isolates is more prevalent in CNS than in S. aureus (6, 17). Furthermore, the observation of in vivo transfer of SCCmec from Staphylococcus epidermidis to S. aureus (31) suggests that CNS may act as a source for SCCmec acquisition by S. aureus. This would be consistent with the finding that SCCmec types present in CNS are more heterogeneous than those in MRSA (11, 18, 32).

Worldwide methicillin-resistant CNS (MRCNS) have been isolated from a number of animals, such as pigs, horses, cows, dogs, and cats (8, 29, 30). Recently, MRSA belonging to sequence type 398 (ST398) emerged in livestock (pigs, veal calves, and poultry) in Europe and North America (10, 23, 30), whereas in Asia, livestock-associated MRSA belonging to ST9 emerged (28). Contact with animals colonized with MRSA has been recognized as a risk factor for human colonization (9, 25). The increasing number of MRSA ST398 transmissions and infections illustrates that this is a public health concern (29).

Although it has been proposed that methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) ST398, highly prevalent in pigs, acquired mecA from coexisting staphylococci (30), the presence of mecA-positive staphylococci in pigs has not been studied and the source of SCCmec in MRSA ST398 is only speculative. Therefore, it was the aim of this study to detect Staphylococcus species harboring SCCmec on pig farms. We demonstrate that a reservoir of mecA-positive CNS coincides with S. aureus on pig farms and that the presence of the same SCCmec types among CNS and S. aureus supports the hypothesis that on pig farms CNS may act as a reservoir for exchange of SCCmec.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This study included 10 pig farms in The Netherlands with different levels of antibiotic usage, which is expressed in animal daily dosages per year. Nasal samples were taken from 5 randomly selected pigs, using dry cotton swabs. In addition, on each farm 5 dust samples were taken using dry cotton swabs. The swabs were immediately transported to the laboratory and processed within 24 h after collection.

The collection of swabs from pigs was approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Utrecht University according to the Dutch Law on Animal Health and Welfare.

Staphylococcal isolation.

The swabs from each farm were pooled in two samples, one with the nasal swabs and one with the dust swabs. Material was eluted in 5 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by vigorous shaking and vortexing for 1 min. One hundred microliters of the obtained sample suspension was inoculated on mannitol-salt agar (bioTRADING, The Netherlands) using 10-fold serial dilutions up to 10−4 and incubated for 72 h at 30°C. An additional 100 μl of undiluted sample suspension was inoculated on Brilliance Staph 24 agar (Oxoid, United Kingdom), an MRSA selective plate, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. From each mannitol-salt agar plate, colonies with typical but diverse staphylococcal morphologies were selected and cultivated on blood agar with 5% sheep blood (bioTRADING, The Netherlands) for further analysis (to a maximum of 5 isolates that displayed the same morphology). Moreover, from the Brilliance Staph 24 agar, up to 5 typical MRSA colonies were selected and subcultured for further analysis. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C on blood agar with 5% sheep blood (bioTRADING, The Netherlands), staphylococcal strains were verified by colony morphology, Gram staining, and catalase reaction.

DNA isolation.

From each isolate, crude DNA was isolated using InstaGene matrix (Bio-Rad, The Netherlands) according to the protocol of the manufacturer.

Identification of mecA-positive staphylococci.

Detection of the mecA gene was carried out by multiplex PCR using primers for mecA (7) and the 16S rRNA gene (27F and 556R) (15) using amplification of the 16S rRNA gene as a positive control for DNA extraction. PCR was carried out in a 20-μl volume containing 1× PCR master mix (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania) with 6 μM mecA primers, 3 μM 16S rRNA gene primers, and 2 μl of crude DNA. The thermal cycling conditions used were 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and the final extension was at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were detected on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

The diversity of mecA-positive isolates was assessed by GTG-fingerprinting PCR analysis according to the protocol of Braem et al., with modifications (3). Briefly, the amplification mixture consisted of a total volume of 25 μl containing 1× PCR buffer (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania), 1.25 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 200 μg bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 pmol primer and 2 U Taq polymerase (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania), and 2 μl DNA solution. Amplifications were carried out using reported amplification conditions (3). The resulting fingerprints were analyzed using the BioNumerics V 6.0 software package (Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium). The similarity among digitized profiles was calculated using Pearson's correlation and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic means (UPGMA) with 2% optimization. Isolates recovered from the same source exhibiting distinct GTG-fingerprinting profiles (similarities less than 95%) were considered to be genetically unrelated and were included for further analysis.

Species identification of selected isolates was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Raw spectra were analyzed by the MALDI Biotyper 2.0 software program (Bruker Daltonics) with default settings. An internal control (Escherichia coli DH5α) was used for calibration before each experiment. Identification scores above 2 or between 1.8 and 2 for duplicate samples were considered to be reliable (4). In isolates with unreliable identification (below 1.8), species determination was performed by sequencing of 16S rRNA genes (15) and tuf genes (21). Sequences were analyzed against all available sequences using the BLAST algorithm. The species was identified when the gene sequences yielded ≥98% sequence similarity with the closest bacterial species sequence in GenBank.

SCCmec typing.

The SCCmec elements were typed by a recommended hierarchical system (13). This included four multiplex PCRs (M-PCRs) according to a protocol reported previously by Kondo et al. (16). In addition, where a noninterpretable type was obtained by M-PCR, a single PCR of each gene was performed. When the ccr complex and mecA complex could not be amplified, no SCCmec type was assigned. For subtyping of the SCCmec type IVa isolates, the ccrB allotype was determined by ccrB sequence typing (20). Positive controls for the M-PCR were the MRSA strains COL/SCCmec type I, N315/SCCmec type II, ANS46c/SCCmec type III, MW2/SCCmec type IVa, and S217/SCCmec type V (clinical isolate from the University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands).

Rapid S. aureus ST398 identification.

All S. aureus were screened for ST398 using a real-time assay based on the detection of the C01 amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) region (27). PCR was carried out in a 20-μl volume containing 1× LightCycler 480 probe master (Roche, Germany) with 0.9 μM CO1 primers (27) and 0.2 μM CO1 probe (5′ Yakima Yellow-ATTGTCAGTATGAATTGCGGT-MGB 3′) and 2 μl of DNA matrix. The real-time PCR cycling conditions used were 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s, and cooling was at 40°C for 10 s. Real-time PCR amplification was carried out with a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche, Germany).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ccrB sequences of the two pig isolates from farm 5, classified as new alleles 417 and 418, have been deposited in www.ccrbtyping.net as isolates F0101-01 and F0101-12, respectively.

RESULTS

Staphylococci recovered from pig farms.

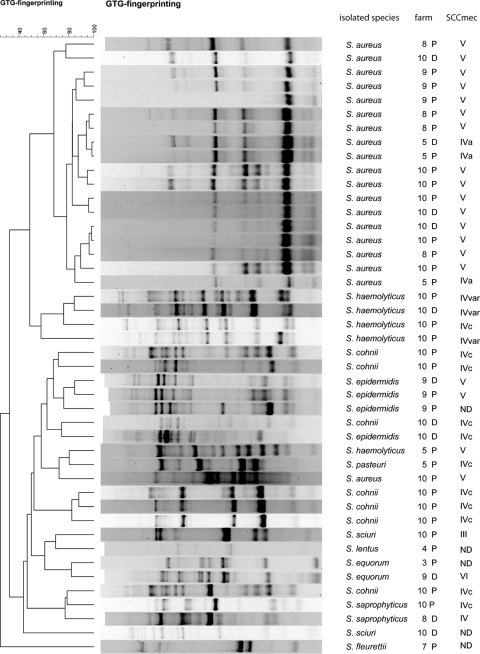

A total of 65 mecA-positive staphylococci were isolated from 7 of the 10 pig farms. From farms 1, 2, and 6, no mecA-positive staphylococci were isolated (Table 1). All analyzed staphylococcal isolates were typeable using GTG fingerprinting (Fig. 1). Isolates recovered from the same source exhibiting distinct GTG-fingerprinting profiles (similarities less than 95%) were considered to be genetically unrelated and were included for further analysis: in total, 44 isolates. Of these 44 mecA-positive staphylococci, 33 (75%) were isolated from nose swabs and 11 (25%) from dust samples. For each isolate, the species could be determined. The most common species recovered from the nasal samples were S. aureus (n = 15; isolated from pigs on 4 farms), Staphylococcus cohnii (n = 6; isolated from pigs on 1 farm), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (n = 4; isolated from pigs on 2 farms), and S. epidermidis (n = 3; from pigs on 1 farm). Single isolates of S. sciuri, Staphylococcus pasteuri, Staphylococcus equorum, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus lentus, and S. fleurettii were recovered from nasal swabs. The staphylococci isolated from the dust on two farms belonged to S. aureus (n = 4 from 2 farms) and S. epidermidis (n = 2 from 2 farms). Also, single isolates of S. haemolyticus, S. saprophyticus, S. cohnii, S. sciuri, and S. equorum were isolated from the dust samples.

Table 1.

Characterization of mecA-positive staphylococcia

| Farm | Staphylococcal species isolated from pig nostril (nb) | SCCmec type(s) | Staphylococcal species isolated from dust (nb) | SCCmec type | No. of ADD/yr | Total no. of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | None | <5 | 0 | ||

| 2 | None | None | <5 | 0 | ||

| 3 | S. equorum (1) | ND | None | <5 | 1 | |

| 4 | S. lentus (1) | ND | None | <5 | 1 | |

| 5 | S. aureus (2) | IVa | S. aureus (1) | IVa | 11.2 | 5 |

| S. pasteuri (1) | IVc | |||||

| S. haemolyticus (1) | V | |||||

| 6 | None | None | 13.1 | 0 | ||

| 7 | S. fleurettii (1) | ND | None | 21 | 1 | |

| 8 | S. aureus (4) | V | S. saprophyticus (1) | IV | 30 | 5 |

| 9 | S. aureus (3) | V | S. equorum (1) | VI | 32 | 7 |

| S. epidermidis (2) | V, ND | S. epidermidis (1) | V | |||

| 10 | S. aureus (6) | V | S. aureus (3) | V | 35 | 24 |

| S. cohnii (6) | IVc | S. cohnii (1) | IVc | |||

| S. sciuri (1) | III | S. sciuri (1) | ND | |||

| S. haemolyticus (3) | IVc, IVvar | S. haemolyticus (1) | IVvar | |||

| S. saprophyticus (1) | IVc | S. epidermidis (1) | IVc | |||

| Total no. of isolates | 33 | 11 | 44 |

ADD/yr, animal daily dosages per year (antibiotic usage); ND, not determined; var, unknown subtype variant.

n, no. of isolates.

Fig 1.

Dendrogram based on the cluster analysis of the (GTG)5-PCR fingerprinting profiles of recovered mecA-positive staphylococci in this study using UPGMA clustering methods of Pearson's correlation coefficients. P, isolate recovered from pig nose; D, isolate recovered from dust.

Species distribution differed between farms. In general, a higher number of mecA-positive isolates were recovered from farms with high antibiotic usage (Table 1). In addition, on farms with high antibiotic usage, a larger number of different mecA-positive Staphylococcus species also were isolated (Table 1).

GTG-PCR fingerprinting.

All analyzed staphylococcal isolates were typeable using GTG fingerprinting. The generated PCR amplicons ranged in size from 200 bp to 8 kb, and the number of PCR products ranged from 4 to 24 bands. GTG fingerprinting showed a high diversity of GTG patterns among the recovered staphylococcal isolates (Fig. 1). The GTG fingerprints grouped the individual species (S. aureus, S. cohnii, S. haemolyticus, S. epidermidis, and S. equorum) in separate clusters, except for one S. aureus isolate. Isolates of S. cohnii, which were all isolated from farm X, were located on 3 different positions in the dendrogram. The single isolates obtained for S. fleuretti, S. pasteuri, and S. lentus clustered separately. The GTG fingerprints of isolates recovered from dust samples and pigs from the same farm clustered together.

Diversity of SCCmec types in staphylococci.

All selected isolates were screened for SCCmec types using a multiplex strategy. In 36 of 44 isolates, known SCCmec types were detected: V (n = 19), IVc (n = 12), IVa (n = 3), III (n = 1), and VI (n = 1). In the remaining 8 isolates, we were not able to detect the exact SCCmec types by using the M-PCR strategy. In 3 isolates, the SCCmec types belonged to a new variant of type IV, which could not be subtyped using the Kondo M-PCR strategy. In 5 isolates, the SCCmec types were nontypeable. Table 1 lists the detected SCCmec types in recovered isolates, and Table 2 shows the nontypeable SCCmec elements.

Table 2.

Characterization of nontypeable SCCmec carried by recovered CNS

SCCmec type V was predominant on the investigated farms. This type was harbored mostly by S. aureus isolates (n = 16/19), which were present on 3 farms. Additionally, SCCmec type V was found in two S. epidermidis isolates and one S. haemolyticus isolate. Furthermore, only on farm 9, SCCmec type V was present in two different species: S. epidermidis and S. aureus. SCCmec type IVc, the second predominant type, was identified in 12 isolates recovered from 2 farms (farms 5 and 10). On farm 10, 4 different species harbored SCCmec IVc (n = 11): S. cohnii (n = 7; pig and dust samples), S. haemolyticus (n = 1; pig), S. pasteuri (n = 1; pig), S. saprophyticus (n = 1; pig), and S. epidermidis (n = 1; dust). SCCmec type IVa was identified only in S. aureus isolates recovered from farm 5, and SCCmec types III and VI were detected in single isolates.

In 3 S. haemolyticus isolates recovered from farm X, the SCCmec type was defined as type IV based on the presence of the ccrA2B2 genes and mecA complex B. However, subtyping based on amplification of the J1 region showed the presence of open reading frame (ORF) E007 in two isolates, which corresponds to SCCmec type I, and for the other S. haemolyticus isolate, subtyping was unsuccessful. These isolates, we concluded, were carrying a new variant of SCCmec type IV (IVvar) (Table 1).

The SCCmec type of 5 isolates, recovered from 5 different farms, could not be determined (Table 2). In 4 isolates, only the presence of a mecA complex B or A could be determined. Moreover, in one mecA-positive S. epidermidis isolate, neither the presence of the ccr genes nor that of the mecA complex could be determined.

To exclude possible transfer of S. aureus SCCmec type IVa from the community, we performed ccrB sequence typing. The ccrB sequences of the two pig isolates from farm 5 were closely related to ccrB2 allele 401 from a human S. aureus isolate in the database and were classified as new alleles 417 and 418. This indicates the presence of new ccrB2 alleles, which until now have not been found in humans but were associated with the pig farm environment.

DISCUSSION

Horizontal gene transfer of the SCCmec element is thought to contribute to the generation of new methicillin-resistant staphylococci, including MRSA. To investigate a potential site of such an exchange of SCCmec elements, our study focused on the presence of SCCmec among the staphylococcal flora present on 10 selected pig farms.

In this study, 10 different methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus species were recovered from 7 pig farms. The most common species was S. aureus, but the majority of the isolates were CNS. Typing of SCCmec from MRCNS has been described for only one other study conducted in pigs. However, in that study, only carriage of S. sciuri with SCCmec type III was described, and methicillin-resistant S. lentus and S. xylosus were isolated but their SCCmec elements were not typed (32).

From the pig nose and dust samples, the same Staphylococcus species were obtained. Typing of the isolates from pig nose and dust samples showed that they were genetically related and suggests transmission of staphylococci between dust and the pig nose. The fact that multiple species were isolated from the pig nose suggests that colonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus species occurs in the nose, which may create the environment for potential horizontal gene transfer.

All S. aureus isolates belonged to ST398 (1, 23). Also, GTG fingerprinting could not differentiate the isolates and supports the clonal spread of MRSA ST398 in pig farms. Remarkably, the species distributions and numbers of recovered mecA-positive staphylococci were different on the investigated farms. In general, a higher number of methicillin-resistant isolates were recovered from farms with high antibiotic usage, and also a larger number of different methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus species were isolated. In the recovered staphylococci, SCCmec typing showed the carriage of known types (III, IVa, IVc, V, and VI). In 3 isolates, new subtypes of SCCmec type IV were found, and in 5 isolates, we were unable to identify the SCCmec element. In the recovered MRSA, we found only SCCmec types V and IVa, which are commonly identified SCCmec types for MRSA ST398 (23); the presence of two different SCCmec types in S. aureus ST398 with the same spa type (data not shown) suggests, as has been shown previously (26), that different SCCmec types have been transferred to an isogenic MSSA isolate. How often this transfer occurs is unknown, but the farm environment, where multiple mecA-positive staphylococci reside, may provide an environment for potential lateral transfer. Another finding of a possible reservoir in pig farms is the finding of S. aureus harboring novel SCCmec variants as defined by ccrB sequencing. The detection of novel ccrB2 alleles, which have not been found in human isolates until now, suggests the possibility that these S. aureus strains were not introduced by human contact.

Our results indicate a large diversity in the J1 region in type IV of SCCmec in CNS. For example, S. cohnii, S. haemolyticus, S. saprophyticus, and S. pasteuri SCCmec type IVc was detected; in two S. haemolyticus isolates, sequences associated with SCCmec type I in SCCmec subtype IV were found; and in one S. haemolyticus isolate, SCCmec type IV could not be subtyped, indicating the presence of novel SCCmec subtypes. This is consistent with the findings of Berglund et al. (2), who reported new types of SCCmec type IV based on variation in the J1 region in MRSA. Our results indicate that on pig farms, type IV and type V are the major SCCmec types in the staphylococcal population. SCCmec type VI, harbored by one isolate of S. equorum, has not been detected in this species before. We detected SCCmec type III only in one isolate of S. sciuri, which was previously reported by Zhang et al. (32). A SCCmec element that was nontypeable with the Kondo PCRs was found in one S. sciuri isolate. SCCmec typing was furthermore impossible in single isolates of S. epidermidis, S. equorum, S. lentus, and S. fleurettii. These findings indicate the presence of novel SCCmec elements in CNS isolates, are in agreement with findings of other studies (11, 18, 32), and show that diversity of SCCmec types in CNS is considerably larger than that in MRSA recovered from the same environment.

MRCNS are considered to be a source for horizontal gene transfer of SCCmec elements to S. aureus. The diversity of SCCmec types among CNS is larger than that among S. aureus (6, 17), and interspecies horizontal transfer of SCCmec from S. epidermidis to S. aureus has recently been documented (31). Moreover, as the study by Nübel et al. indicated, transfer of SCCmec to S. aureus is not a rare event (19). All of these observations support the hypothesis that CNS may act as the SCCmec reservoir for interspecies exchange of this element among Staphylococcus species. Our results are also consistent with this hypothesis, since the S. aureus and S. epidermidis isolates shared the SCCmec V element and because of the presence of SCCmec type IVc in four staphylococcal species. Our study showed a large diversity of SCCmec among the staphylococci present in pig farms, which may be a risk for interspecies lateral transfer of SCCmec between CNS and S. aureus. Detailed genetic characterization of the SCCmec types in these strains is necessary to confirm that exactly the same SCCmec elements are present in these Staphylococcus species.

The novel SCCmec types found in this study, as well as type IVc, have not previously been found in MRSA ST398. Transfer of these subtypes to S. aureus, generating novel MRSA strains, cannot be excluded, and longitudinal surveillance will be required to follow dissemination of novel SCCmec types in S. aureus ST398 or other sequence types.

A limitation of our study is that only 10 farms were included. This did not allow us to draw conclusions about the relationship between antibiotic use and the number of different methicillin-resistant staphylococcus species or the bacterial load. Furthermore, additional SCCmec types, both known and novel, may be present in the farm environment while not being detected because of the limited number of farms included.

In conclusion, SCCmec elements present in staphylococci on pig farms are highly heterogeneous. These staphylococci may act as a source for transfer of SCCmec to S. aureus. Although direct proof of transfer was not obtained in this study, SCCmec type V was shared in S. aureus and S. epidermidis and SCCmec type IVc was present in 4 MRCNS, indicating the possibility of interspecies transfer of SCCmec elements in pig farms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by European Union PF7 grant no. CONCORD-222718.

We thank Arie van Nes, Tijs Tobias from Utrecht University, and Gerard van Eijden from Animal Care Putten for helping with farm selection and collecting the samples. We are grateful to Neeltje Carpaij, from the University Medical Center Utrecht, for help with MALDI-TOF analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Armand-Lefevre L, Ruimy R, Andremont A. 2005. Clonal comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from healthy pig farmers, human controls, and pigs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:711–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berglund C, et al. 2009. Genetic diversity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying type IV SCCmec in Orebro County and the western region of Sweden. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braem G, et al. 2011. (GTG)(5)-PCR fingerprinting for the classification and identification of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species from bovine milk and teat apices: a comparison of type strains and field isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 147:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carpaij N, Willems RJ, Bonten MJ, Fluit AC. 2011. Comparison of the identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and tuf sequencing. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:1169–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Couto I, et al. 1996. Ubiquitous presence of a mecA homologue in natural isolates of Staphylococcus sciuri. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:377–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diekema DJ, et al. 2001. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl 2):S114–S132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fluit AC, Wielders CLC, Verhoef J, Schmitz FJ. 2001. Epidemiology and susceptibility of 3,051 Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 25 university hospitals participating in the European SENTRY study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3727–3732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garza-Gonzalez E, Morfin-Otero R, Llaca-Diaz JM, Rodriguez-Noriega E. 2010. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) in methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci. A review and the experience in a tertiary-care setting. Epidemiol. Infect. 138:645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graveland H, Wagenaar JA, Bergs K, Heesterbeek H, Heederik D. 2011. Persistence of livestock associated MRSA CC398 in humans is dependent on intensity of animal contact. PLoS One 6:e16830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graveland H, et al. 2010. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in veal calf farming: human MRSA carriage related with animal antimicrobial usage and farm hygiene. PLoS One 5:e10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanssen AM, Sollid JUE. 2006. SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 46:8–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartman B, Tomasz A. 1981. Altered penicillin-binding proteins in methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 19:726–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Elements 2009. Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4961–4967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ito T, Katayama Y, Hiramatsu K. 1999. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1449–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kolbert CP, et al. 2004. 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis for identification of bacteria in a clinical microbiology laboratory, p 361–377. In Persing DH, Tenover FC, Versalovic J, Tang Y, Unger ER, Relman DA, White TJ. (ed), Molecular microbiology. Diagnostic principles and practice, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kondo Y, et al. 2007. Combination of multiplex PCRs for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type assignment: rapid identification system for mec, ccr, and major differences in junkyard regions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:264–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martins A, Cunha Mde L. 2007. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci: epidemiological and molecular aspects. Microbiol. Immunol. 51:787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mombach Pinheiro Machado AB, Reiter KC, Paiva RM, Barth AL. 2007. Distribution of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types I, II, III and IV in coagulase-negative staphylococci from patients attending a tertiary hospital in southern Brazil. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1328–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nubel U, et al. 2008. Frequent emergence and limited geographic dispersal of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14130–14135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oliveira DC, et al. 2008. ccrB typing tool: an online resource for staphylococci ccrB sequence typing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:959–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sakai H, et al. 2004. Simultaneous detection of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci in positive blood cultures by real-time PCR with two fluorescence resonance energy transfer probe sets. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5739–5744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schnellmann C, et al. 2006. Presence of new mecA and mph(C) variants conferring antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus spp. isolated from the skin of horses before and after clinic admission. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4444–4454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith TC, Pearson N. 2011. The emergence of Staphylococcus aureus ST398. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 11:327–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsubakishita S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Sasaki T, Hiramatsu K. 2010. Origin and molecular evolution of the determinant of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4352–4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van den Broek IV, et al. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in people living and working in pig farms. Epidemiol. Infect. 137:700–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Duijkeren E, et al. 2008. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains between different kinds of pig farms. Vet. Microbiol. 126:383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Wamel WJ, et al. 2010. Short term micro-evolution and PCR-detection of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 398. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:119–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wagenaar JA, et al. 2009. Unexpected sequence types in livestock associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): MRSA ST9 and a single locus variant of ST9 in pig farming in China. Vet. Microbiol. 139:405–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weese JS. 2010. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in animals. ILAR J. 51:233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weese JS, van Duijkeren E. 2010. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in veterinary medicine. Vet. Microbiol. 140:418–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wielders CLC, et al. 2001. In-vivo transfer of mecA DNA to Staphylococcus aureus [corrected]. Lancet 357:1674–1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Agidi S, LeJeune JT. 2009. Diversity of staphylococcal cassette chromosome in coagulase-negative staphylococci from animal sources. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107:1375–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]