Abstract

Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), a key driver of growth in the majority of breast cancers, contains an unstructured transactivation domain (AF1) in its N terminus that is a convergence point for growth factor and hormonal activation. This domain is controlled by phosphorylation, but how phosphorylation impacts AF1 structure and function is unclear. We found that serine 118 (S118) phosphorylation of the ERα AF1 region in response to estrogen (agonist), tamoxifen (antagonist), and growth factors results in recruitment of the peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1. Phosphorylation of S118 is critical for Pin1 binding, and mutation of S118 to alanine prevents this association. Importantly, Pin1 isomerizes the serine118-proline119 bond from a cis to trans isomer, with a concomitant increase in AF1 transcriptional activity. Pin1 overexpression promotes ligand-independent and tamoxifen-inducible activity of ERα and growth of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Pin1 expression correlates with proliferation in ERα-positive rat mammary tumors. These results establish phosphorylation-coupled proline isomerization as a mechanism modulating AF1 functional activity and provide insight into the role of a conformational switch in the functional regulation of the intrinsically disordered transactivation domain of ERα.

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors, mediates the actions of estrogen in normal physiology and disease (17). ERα is expressed in the normal mammary gland and in 70% of human breast cancers and is a key driver of breast cell proliferation (16, 26, 83). Directed overexpression of ERα in the mammary gland is sufficient to induce hyperplasia, and blockade of ERα activity by hormonal therapies (aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen, and fulvestrant) reduces recurrence and improves clinical outcomes of ERα-positive breast cancer patients (19, 22). Two activation functions mediate the transcriptional activity of ERα, a C-terminal ligand-dependent AF2 and an N-terminal ligand-independent AF1 (89). Regulation of ERα activity via the C-terminal AF2 has been well-characterized through biochemical and crystallographic studies and forms the basis for our understanding of hormonal therapy for breast cancer (10, 34, 84). In the canonical activation pathway, ligand binding initiates C-terminal structural rearrangements that facilitate downstream events, including dimerization, DNA binding, and coregulator interactions, ultimately engaging the basal transcriptional machinery to regulate gene expression. However, ERα can also be activated by growth factors and kinases, which phosphorylate the receptor N terminus and other domains to regulate transcription in the absence of direct ligand engagement (for reviews, see references 27, 47, 75, 94, and 95). In contrast to the C-terminal AF2 domain, biochemical and structural mechanisms that control N-terminal AF1 remain poorly understood (48, 91).

Multiple challenges have hindered molecular dissection of AF1 regulation. First, AF1 resides in the receptor N terminus, which is an intrinsically disordered region and for which limited structural data are available (91). Second, although the importance of phosphorylation in the regulation of this domain has been established, it is complicated by multiple sites of phosphorylation (3, 47). Focus has been drawn to serine 118 (S118), since a single point mutation to alanine impairs both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent ERα activity (15, 20a, 42, 90). Third, phos-phorylation of S118 is induced by hormonal and nonhormonal activators such as estrogens and growth factors (2, 11, 42, 49), kinases such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (cdk7), and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) (2, 11, 14, 51, 65), as well as the ERα inhibitor tamoxifen (33, 51, 80). S118 phosphorylation has also been shown to recruit both a transcription coactivator (p68 RNA helicase and splicing factor SF3a p120) and the corepressor stromelysin 1 platelet-derived growth factor-responsive element-binding protein (SPBP) (25, 31, 62, 92). Finally, S118 phosphorylation has been implicated in both increased and decreased ERα protein stability (7, 12, 36, 61, 90). Taken together, these observations point to a complex role of phosphorylation, and in particular for S118, in the regulation of AF1 that remains unresolved.

The N-terminal phosphorylation sites in ERα and several nuclear receptors consist of a conserved serine/threonine-proline (S/T-P) motif, which is a recognition site for proline-directed kinases (75). When phosphorylated, the phospho-S/T-P (pS/T-P) site also becomes a potential substrate for the peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1. Pin1 is a unique phosphorylation-dependent prolyl isomerase composed of an N-terminal WW domain, involved in protein interaction, and a catalytic C-terminal prolyl isomerase (PPIase) domain. The WW domain preferentially binds to the pS/T-P motif, and the PPIase domain catalyzes cis-trans isomerization of the prolyl bond to regulate signaling (53–56, 73, 97, 100). Such Pin1-catalyzed conformational regulation after phosphorylation often functions as a molecular timer, regulating many key proteins in diverse cellular processes (53, 56). Importantly, Pin1 is overexpressed and correlates with poor patient outcome in many cancers, including breast cancer (88, 99). This raises the possibility that Pin1-mediated isomerization of phosphorylated ERα regulates N-terminal functions in breast cancer cells.

Here, we establish that ERα AF1 activity is regulated by S118 phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of Pin1. Pin1 increases AF1-dependent transcription through a PPIase-dependent mechanism. We show that Pin1 binds directly to pS118 ERα and isomerizes ERα AF1 pS118-P119 from cis to trans. Pin1 imparts increased proliferation potential to breast cancer cells. In vivo, Pin1 expression is strongly associated with proliferation of ERα-positive mammary cancers. These data suggest that like AF2, AF1 function can be regulated through conformational change, and they identify prolyl isomerization as a new mode of ERα regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression plasmids.

Gal4-DNA binding domain (Gal4-DBD) constructs were gifts from Zafar Nawaz (University of Miami) and have been described elsewhere (13). ERα expression vectors (wild type, hemagglutinin [HA] tagged, Sl18A, and L540Q) were constructed in an LHL-CA backbone (90). The ERα L540Q mutant was a gift from Benita Katzenellenbogen (University of Illinois—Urbana-Champaign) (37). Reporter genes consisting of the minimal estrogen response element and a thymidine kinase promoter driving the luciferase gene (ERE-tk-Luc) were previously described (93), and a Gal4 binding luciferase reporter (pFR-Luc) was obtained from Agilent Technologies, CA. The construct RasV12G was a gift from Jing Zhang (University of Wisconsin—Madison) (102). Flag-Pin1 was made as described previously (52). Flag-Pin1 mutants K63A and W34A were made using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, CA). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-carrying plasmids were constructed as reported elsewhere (86). Flag-FKBP51 was provided by Edwin Sanchez (Medical College of Ohio). Constructs of ERα with C-terminally tagged Renilla luciferase (ERα-RLUC) and yellow fluorescent protein (ERα-YFP) were a gift from Wei Xu (70).

Cell culture and treatments.

MCF-7, MCF-7 cells expressing GFP or GFP-Pin1, HEK293T cells, a stable HEK293 cell line expressing HA-ERα or HA-S118A ERα (90), and MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained under standard culture conditions as described in reference 24. Stable MCF-7 cells expressing GFP-tagged Pin1 or GFP vector were generated by viral infection and selection with 2 μg/ml puromycin. Multiple independent stable pools were selected, and protein expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis with Pin1 antibody (57) and GFP-specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). MCF-7-5C, a tamoxifen-resistant cell line (39), was maintained in phenol red-free RPMI (Invitrogen, CA) supplemented with 10% dextran–charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, nonessential amino acids (NEAA), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA), and 10 μg/ml of insulin from bovine pancreas (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). In experiments involving treatment with ethanol (EtOH), 17β-estradiol (E2), epidermal growth factor (EGF), or 4-hydroxytamoxifen (OHT), cells were placed in estrogen-deprived medium consisting of phenol red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Cellgro, Mediatech Inc., VA) with 10% dextran–charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum for 3 days prior to the addition of hormone or vehicle. For EGF treatments, the medium was changed to phenol red-free DMEM or Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, CA) overnight prior to treatment. The treatments were carried out for the times indicated below in the figure legends.

Animals.

Fifty-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratory) were ovariectomized, implanted with silastic pellets producing physiological levels of E2 (2.5 mg/1-cm silastic pellet), and treated with 50 mg/kg of body weight 7,12-dimethylbenz[α]anthracene (DMBA) intragastrically to induce mammary tumors as previously described (41). Tumor-bearing rats were euthanized 2 h after intraperitoneal injection with 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU; 70 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). All animal handling procedures were approved by the Michigan State University (MSU) Committee on Animal Use and Care.

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry.

For mammary tumor sections, labeling with mouse monoclonal anti-Pin1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (anti-BrdU detection kit; Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) was performed as previously described (40). Images were captured with a Nikon inverted epifluorescence microscope (Mager Scientific) and analyzed with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). Captured images were used to quantitate Pin1+ or BrdU+ cells detected by immunofluorescent labeling, and the number of positive cells was expressed as the percentage of total tumor cells counted.

Immunocytochemistry in MCF-7 cells was performed as previously described (29). Primary antibodies included anti-ERα (HC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) and anti-Pin1 (57). Secondary antibodies included anti-mouse IgG–fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or anti-rabbit IgG–rhodamine red (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, CA). Images were acquired using an Olympus fluorescence microscope with 20× magnification and exported to Adobe Photoshop.

Reporter gene assays.

Assays were performed as previously described (90) in MDA-MB-231 cells or HEK293T cells as indicated in the figure legends. Expression constructs included LHL-CA-ERα or L540Q mutant, Gal4 fusion constructs consisting of Gal4-DBD fused to AF1, AF2, or Gal4-DBD alone, Flag- or GFP-tagged Pin1 and mutants, and Flag-FKBP51. Reporter genes consisted of ERE-tk-Luc or pFR-Luc, as appropriate. Equal amounts of DNA were transfected, and transfection efficiency was controlled by cotransfection with cytomegalovirus β-galactosidase (CMV–β-Gal). Luciferase (Luciferase assay system; Promega, Madison, WI) and β-galactosidase (Glacto-Light Plus; Tropix Inc., MA) assays were performed as per the manufacturers' protocols. Treatments conditions with EtOH, E2, EGF, or OHT are described in the figure legends. Treatment with EGF was performed in reduced serum Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, CA).

Coimmunoprecipitation and glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown.

Coimmunoprecipitation was performed in MCF-7 cells starved in serum-free DMEM with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 3 days. Cells were then stimulated with 0.1% EtOH or 10 nM E2 for 30 min with 1 μM okadaic acid (Roche, NJ) added during the final 10 min. Cells were lysed in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 40 mM NaCl, 0.2% NP-40, 15% glycerol, 1 mM Juglone, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Pin1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or normal mouse IgG antibody–protein A/G 1:1 agarose beads (Invitrogen, CA) complexes were allowed to form for 45 min, and cell lysates were incubated with the antibody-bead complexes for 2 h. The antibody-bound complex was washed 4 times with lysis buffer, and proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting for Pin1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or ERα (Stressgen; Enzo Life Sciences, NJ) using appropriate antibodies. Input lanes contained 1% whole-cell extracts prior to immunoprecipitation.

All GST-tagged proteins were expressed and purified as previously reported (100, 103). GST pulldown assays were performed as described previously (103) with purified GST, GST-Pin1, GST-WW, GST-PPIase, and GST-Pin1 W34A and whole-cell extracts of MCF-7 cells or HEK293 cells with stable or transient expression of HA-ER and HA-ERα S118A (90) treated with E2, EGF, EtOH, OHT, or alkaline phosphatase (PPase) as indicated in the figure legends. For treatment with EGF, medium was changed to phenol red/serum-free DMEM for overnight incubation.

In vitro phosphorylation of the ERα39–160 fragment.

The purified ERα39–160 fragment with and without uniform (U) 15N labeling was produced at the Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics (CESG) at UW—Madison by using an Escherichia coli cell-based platform (60). Commercial MAPK containing an N-terminal GST tag (Millipore, MA) was used to phosphorylate the ERα39–160 fragment. The kinase reaction was carried out as described previously (51) in 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol (kinase buffer), 10 μM ATP, and ERα39–160 in the presence and absence of 5 μg of kinase. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 4 h. Phosphorylation of ERα39–160 at S118 was confirmed by Western blotting using pS118 ERα-specific antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, MA). Site-specific phosphorylation at S118 was further confirmed by Western blotting with antibody specific for phosphoserines 104/106 in ERα (Cell Signaling Technology, MA). Equivalent loading was confirmed by reprobing with ERα-specific antibody (H184; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The phosphorylated fragment was further purified by incubating the reaction mixture with glutathione (GSH)-agarose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in the presence of apigenin (Sigma) to block MAPK activity.

In vitro dephosphorylation assay.

Purified, in vitro-phosphorylated ERα39–160 fragment (120 ng) was incubated with 100 ng of purified PP2A holoenzyme (a gift from Yongna Xing, UW—Madison) and 2 μg of purified GST (control) or GST-Pin1 in kinase buffer with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 50 μM MnCl2 in the presence or absence of 10 μM Juglone (Pin1 inhibitor; Sigma) at 30°C. The reaction was terminated with addition of SDS sample buffer at the indicated times, and phosphorylation was assessed by Western blotting using pS118 ERα-specific antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, MA). Equivalent loading was confirmed by reprobing with ERα-specific antibody (H184; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

NMR spectroscopy.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) samples contained 0.5 mM [U-15N]ERα39–160 (either nonphosphorylated or phosphorylated), 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 6 mM sodium phosphate, 60 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, and 10 mM ATP. The solvent was 90% H2O–10% D2O. The pH was adjusted to 7.0. Two-dimensional (2D) 1H-15N heteronuclear single-quantum correlation (HSQC) spectra of [U-15N]ERα39–160 and phosphorylated [U-15N]ERα39–160 were acquired in the absence of Pin1; then, the changes in the amide chemical shifts were monitored as Pin1 was added to a maximum of 10:1 (Pin1:ERα39–160). NMR data were acquired on a Varian Inova 600-MHz (1H frequency) spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe; the NMR probe temperature was maintained at 25°C. 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra (43) were acquired with a total spectral acquisition time of 1.5 h for each sample. All NMR spectra were processed with nmrPipe (18) and analyzed using XEASY (4).

Far-Western blotting assay.

The far-Western blotting method was previously described (23). Briefly, phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERα39–160 fragments were separated by gradient SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, MA). Membranes were incubated with GST, GST Pin1, or GST Pin1 S16E proteins for 4 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Following a rinse with wash buffer 1 (0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and wash buffer 2 (0.2% Triton X-100 and 100 mM KCl in PBS), Western blot analysis was performed on the membrane with anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

BRET assay.

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays were conducted as described in reference 70. Briefly, HEK293T cells were placed in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dextran–charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (estrogen deprived). The cells were then first transfected with either empty vector or Flag-Pin1. After 24 h, cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding ERα fusion proteins with a C-terminal Renilla luciferase (ERα-RLUC) or ERα-YFP. These fusion proteins have been well characterized for their functional activities (70). Control wells were transfected with ERα-RLUC and an empty vector or pCMX-YFP for background and bystander calculations. Following treatment of cells with EtOH for 1 h, coelententerzine-h (Promega, WI) was added to a final concentration of 5 μM per well. Emission levels at 450 and 540 nm were measured using a Synergy plate reader (BioTek Instruments, VT). BRET ratios were calculated, including correction for signals from random collision, i.e., bystander BRET, as described in reference 70.

Growth assays.

Anchorage-independent soft agar colony formation assays using MCF-7 cells transfected with either Pin1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) or scrambled (scr) siRNA (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were conducted using 0.8% SeaPlaque agarose (Cambrex) as previously described (71). Colonies were visualized by staining with 0.005% crystal violet solution, and numbers were determined by manual counting. Tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer MCF-7-5C cells (39) were placed in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dextran–charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (estrogen deprived) and were transfected with Pin1 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (Qiagen, CA) followed by 1 μM OHT treatment for 0, 24, or 48 h. At the indicated times, MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma, St. Louis, MO] was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and cell growth was measured using the manufacturer's protocol. MCF-7 cells overexpressing GFP or GFP-Pin1 were treated with 1 μM OHT for 0, 24, 48, or 72 h, and growth was assessed by crystal violet staining in which cells were stained with 0.4% crystal violet solution (Sigma, MO) for 10 min, washed with water, and lysed in 50% methanol for 10 min with gently shaking. The optical density of the lysis solution was measured at a 540-nm wavelength.

Statistical analysis.

Student's t test was used to assess significant differences between control and treated samples using Microcal Origin software (OriginLab Corporation, MA). Correlation of Pin1 and BrdU uptake was calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient function in Microsoft Excel. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant and are indicated by asterisks in the figures.

RESULTS

Pin1 is necessary for optimal growth of ERα-positive breast cancer cells.

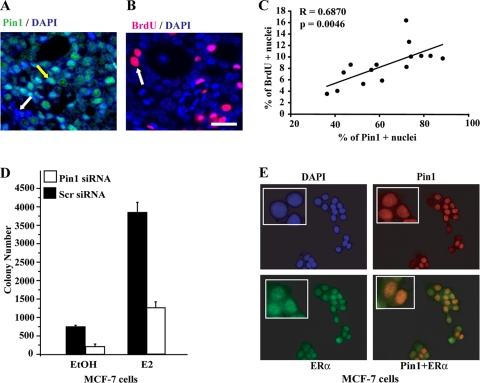

Hormone-dependent ERα+ mammary tumors were induced by treatment of ovariectomized rats with the carcinogen 7,12-dimethylbenz[α]anthracene and exogenous 17β-estradiol (E2) as described in reference 41. To determine whether Pin1 plays a role in ERα-dependent tumor growth in vivo, Pin1 expression and proliferation were evaluated in individual tumors. In all tumors examined (n = 15), 28 to 88% (mean, 57%; median, 52%) of tumor cells expressed nuclear Pin1 (Fig. 1A, yellow arrow). The proliferation rate, as assessed by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 1B), was significantly correlated (P < 0.005) with nuclear Pin1 expression (Fig. 1C), providing initial evidence that Pin1 is related to growth of ERα+ tumors. Next, we asked if ERα+ breast cancer cells are dependent on Pin1 for growth by using anchorage-independent colony formation assays and siRNA knockdown techniques. MCF-7 cells transfected with scr siRNA showed the expected increase in colony number upon treatment with E2 (Fig. 1D). However, knockdown of Pin1 markedly decreased (∼3.5-fold) the number of colonies in both vehicle (EtOH)-treated and E2-treated cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that Pin1 was also nuclear in MCF-7 cells and colocalized with ERα (Fig. 1E). Thus, Pin1 is functionally significant in growth control of ERα-dependent breast tumors and MCF-7 breast cancer cells, potentially through regulation of ERα activity.

Fig 1.

Pin1 is important for growth of ERα-positive breast cancer cells. (A and B) Immunohistochemistry of Pin1 and BrdU in mammary tumors in carcinogen-treated ovariectomized rats implanted with pellets releasing E2. Shown are representative images of Pin1 (green), BrdU (magenta), and nuclear diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). Merged images show nuclear Pin1 (teal) with a nuclear Pin1-positive cell pointed out with a yellow arrow and a Pin1− cell indicated with a white arrow (A). A BrdU+ proliferating cell is indicated with a white arrow (B). Bar, 50 μm. (C) Pin1 expression correlates with proliferation. Individual mammary tumors (n = 15) are represented by a single dot. The numbers of Pin1+ or BrdU+ cells detected by immunofluorescent labeling were quantified from captured images, and the numbers of positive cells are expressed as the percentage of total tumor cells counted. Results are means ± SEM. Correlation coefficient R = 0.6871 (P < 0.005). (D) Pin1 is essential for growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. MCF-7 cells were transfected with Pin1 siRNA or control scrambled (Scr) siRNA and treated with EtOH or 10 nM E2. Growth was assessed by soft agar colony formation assay after 14 to 16 days of treatment. The number of colonies was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are means ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. (E) Immunocytochemistry of Pin1 and ERα in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. MCF-7 cells were stained for nuclear DAPI (blue), Pin1 (red), and ERα (green). The insets shows positive cells in a magnified image. A merged image of Pin1 and ERα is shown in yellow.

ERα AF1 transcriptional function is regulated by Pin1 binding and catalytic activities.

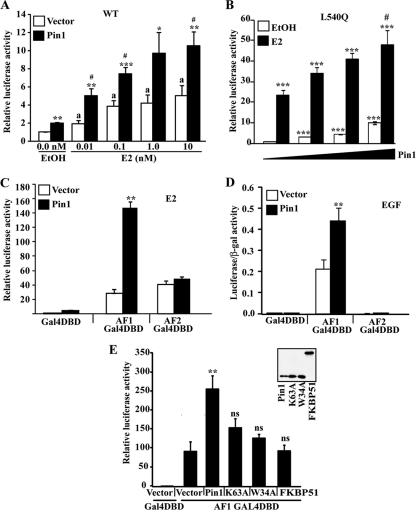

Possible regulation of ERα transactivation by Pin1 was previously suggested by the results of Yi et al., who showed that estrogen-dependent induction of TFF1, a direct target gene of ERα, was diminished by Pin1 knockdown (101). Expanding on this observation, we tested whether Pin1 directly regulated ERα transcriptional function. Reporter gene assays were carried out with transfected wild-type (WT) ERα and Pin1 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by using a defined reporter consisting of a minimal estrogen response element (ERE) and a thymidine kinase promoter driving luciferase gene (ERE-tk-Luc). In agreement with previous findings (101), Pin1 increased ERα-dependent reporter gene activity (Fig. 2A). Pin1's ability to enhance ERα-dependent transcription was further confirmed in MCF-7 MVLN cells with a stably integrated ERE reporter (69) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). However, we noticed that Pin1 significantly increased ERα activity in both the absence of E2 (EtOH control) and at low concentrations of E2 (Fig. 2A). The ability of Pin1 to regulate ERα transcription, under E2-depleted conditions, prompted us to independently assess Pin1 regulation of isolated ERα transactivation domains.

Fig 2.

Pin1 enhances ERα transcriptional function through the AF1 region. (A and B) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with WT ERα (A) or mutant L540Q ERα (B) and empty vector or Flag-Pin1, ERE-tk-Luc, or CMV–β-Gal. (A) Cells were transfected with a constant amount of 500 ng empty vector or Flag-Pin1 and then treated with EtOH or various concentrations of E2 as indicated for 24 h. (B) Cells were transfected with various amounts of Flag-Pin1 (0 to 3 μg) and then treated with EtOH or 10 nM E2 for 24 h. Luciferase and β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activities were measured as per the manufacturer's protocol (see Materials and Methods). Luciferase values were normalized to β-galactosidase levels to control for transfection efficiency. Shown are the fold changes in the activity of luciferase/β-Gal relative to that in EtOH-treated vector-transfected cells. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells were cotransfected with 500 ng of Flag-Pin1 or empty vector and 100 ng of fusion proteins consisting of isolated ERα transactivation domains and Gal4-fusion constructs (Gal4-DBD, AF1 Gal4-DBD, or AF2 Gal4-DBD). Reporter constructs consisted of Gal4 binding luciferase reporter (pFR-Luc) and CMV–β-Gal as a control for transfection efficiency. Cells were then treated with EtOH or 10 nM E2 for 24 h. Relative luciferase activity represents the fold change in normalized luciferase/β-Gal activity relative to that of Gal4-DBD/vector-transfected cells. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected as described for panel C with Flag-Pin1 or empty vector or Gal4-fusion constructs (Gal4-DBD, AF1 Gal4-DBD, or AF2 Gal4-DBD) along with reporter constructs pFR-Luc and CMV–β-Gal. Cells were treated with 0.1 μg/ml EGF overnight. Shown are luciferase/β-Gal ratios. (E) Reporter assays were carried out as described for panel D in HEK293T cells transfected with Gal4-DBD or AF1 Gal4-DBD and empty vector, Flag-Pin1, Flag-Pin1 K63A, Flag-Pin1 W34A, or Flag-FKBP51. Reporter constructs included pFR-Luc and CMV–β-Gal. Relative luciferase activities are shown, as in panel C. The inset shows expression of Flag-Pin1, Flag-Pin1 K63A, Flag-Pin1 W34A (molecular mass, ∼19 kDa), and Flag-FKBP51 (molecular mass, ∼52 kDa), assessed by Western blotting using a Flag-specific antibody. Data in all panels are represented as means ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001, comparing EtOH- (A and B), E2- (C and E), or EGF-treated (D) Pin1- and vector-transfected samples. #, P < 0.05, comparing Pin1- and vector-transfected E2-treated samples (A and B); a, P < 0.05 comparing EtOH- and E2-treated vector-only transfected cells; ns, not significant (P > 0.05) for vector-transfected versus Pin1 mutant/FKBP51-transfected samples (E).

To begin to define the mechanism by which Pin1 regulates ERα transcriptional activity, we employed an ERα mutant (L540Q) that disrupts the AF2 function by interfering with coactivator interactions (1, 37). Interestingly, Pin1 increased the transcriptional activity of the L540Q mutant in both the presence and absence of E2 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, examination of transcriptional activation by isolated AF1 or AF2 domains tethered to a Gal4-DBD revealed that Pin1 failed to stimulate AF2 function (Fig. 2C) and instead increased AF1 activity by ∼5-fold over control cells. A similar increase in Pin1-induced AF1 activity was detected when cells were treated with EGF (Fig. 2D) or when transfected with a constitutively active Ras mutant (RasV12G) (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material), both of which are known to selectively act on AF1 through phosphorylation by activating the MAPK pathway (11). These results imply that Pin1 can enhance both estrogen- and growth factor-inducible AF1 activities. The W34A mutation in the WW domain and K63A mutation in the PPIase domain abolish binding and the isomerase activity of Pin1, respectively (77). To test if the catalytic and binding activities of Pin1 are required for enhancement of AF1 function, we overexpressed Flag-Pin1, Flag-Pin1 K63A, and Flag-Pin1 W34A in HEK293T cells and measured the transcriptional potential of AF1 Gal4-DBD. Neither mutant significantly increased AF1 activity (Fig. 2E). Similarly, Pin1 lacking the catalytic PPIase domain (GFP-WW) was also unable to enhance AF1 activity (see Fig. S1C). The increase in AF1 activity appeared to be Pin1 specific, as overexpression of another prolyl cis/trans isomerase FK506 binding immunophilin (FKBP51) did not enhance AF1 transactivation (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these data indicate that Pin1 stimulates ERα transcriptional activity via the AF1 domain in a manner that requires both the catalytic activity and substrate binding functions of Pin1.

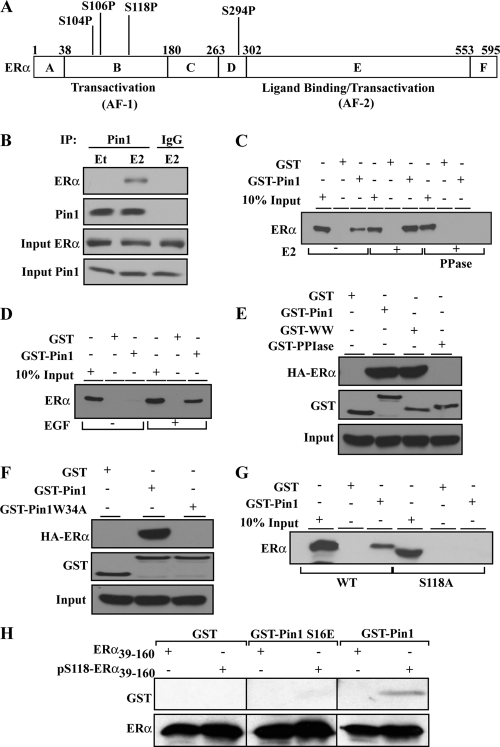

Phosphorylation of ERα at S118 is necessary for Pin1 association with ERα.

We next assessed the possibility that ERα might be a direct target of Pin1. ERα contains four putative S-P motifs (S104P, S106P, S118P, and S294P) (Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation of any of these serine residues could create a Pin1 binding site. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments performed with extracts from MCF-7 cells that were maintained in serum-free medium showed that endogenous Pin1 and ERα are in a protein complex (Fig. 3B). This interaction was detectable upon E2 treatment, consistent with E2-stimulated phosphorylation of AF1 (14). Pin1 interaction with ERα was further confirmed by a GST pulldown assay using GST or GST-Pin1 and cell extracts from estrogen-depleted MCF-7 cells supplemented with 10% dextran–charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Fig. 3C). While E2 increased Pin1 recruitment to ERα, Pin1 was also detected in the absence of E2; however, this interaction was abolished by PPase treatment of the extracts (Fig. 3C), indicating the requirement for phosphorylation. We thus asked whether growth factors, which are present in estrogen-depleted medium, could account for Pin1-ERα interactions under these conditions. MCF-7 cells were thus maintained in serum-free medium and treated with EGF. GST pulldown experiments showed that in the absence of serum, Pin1 did not associate with ERα in cell extracts, but EGF stimulation was sufficient to promote Pin1 recruitment to the ERα complex (Fig. 3D). Accordingly, Pin1 substrate binding WW domain (Fig. 3E) and, specifically, tryptophan (W34) within this domain (77), were required for ERα association (Fig. 3F). Both E2 and EGF induce phosphorylation of ERα of S118, albeit via different kinase pathways (14, 42). Mutation of S118 to alanine abolished the Pin1-ERα association (Fig. 3G). To assess the direct interaction between pS118 ERα AF1 and Pin1, we generated a purified AF1 fragment consisting of amino acids 39 to 160 (ERα39–160) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) that could be phosphorylated in vitro with MAPK (Fig. 4A). By far-Western analysis, blots of unphosphorylated ERα39–160 or pS118-ERα39–160 were hybridized with purified recombinant GST-Pin1, GST–Pin1-S16E (binding-deficient mutant), or GST as a control. Probing blots with GST antibody showed that GST-Pin1, but not GST–Pin1-S16E or GST alone, interacted with pS118-ERα39–160 and not with ERα39–160 (Fig. 3H). Thus, Pin1 can directly recognize the pS118-P119 moiety in the ERα AF1 domain. Thus, inducible phosphorylation of ERα at S118 is necessary to bring Pin1 into the ERα complex, where Pin1 can bind directly to pS118-ERα through the substrate binding WW domain.

Fig 3.

Pin1 directly interacts with phosphorylated ERα through its WW domain. (A) Schematic illustration of full-length ERα, showing S/T-P motifs and potential Pin1 binding sites. (B) MCF-7 cells extracts treated with EtOH or 10 nM E2 were immunoprecipitated with Pin1 antibody or normal mouse IgG and then Western blotted for ERα and Pin1 as described in Materials and Methods. Input lanes show Western blot results for Pin1 and ERα in cell extracts before immunoprecipitation. (C) GST pulldown assays were performed with extracts from MCF-7 cells treated with (+) or without (-) 10 nM E2 for 30 min in the presence or absence of PPase. Shown are Western blot analyses results for ERα following incubation with GST-Sepharose beads and GST proteins. (D) GST pulldown assays were performed using extracts from MCF-7 cells treated with (+) or without (-) 0.1 μg/ml of EGF as described for panel C. Data show representative Western blot analysis results for ERα. (E) GST pulldown assays were performed with extracts from stable HEK293 cells expressing HA-tagged wild-type ERα treated with 10 nM E2 for 30 min and incubated with GST, GST-Pin1, GST-WW (Pin1 mutant lacking the PPIase domain), or GST-PPIase (Pin1 mutant lacking the WW domain). Shown is a representative Western blot with an anti-HA antibody for ERα (HA-ERα) and an anti-GST antibody for GST. Results from Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody for ERα in cell extracts prior to pull down is shown in the input panel. (F) GST pulldown assays were performed as described for panel E using GST, GST-Pin1, and GST-Pin1 W34A (substrate binding Pin1 point mutant). Shown is a representative Western blot analysis for ERα (HA) and GST. The input panel represents Western blot analysis results for ERα in cell extracts prior to pulldown. (G) A GST pulldown assay was performed using cell extracts from HEK293 cells stably expressing WT or S118 phosphorylation site mutant (S118A) ERα that had been stimulated with 10 nM E2 as for panel C. Shown is a representative Western blot analysis for ERα. (H) Pin1 binds directly to the phosphorylated ERα fragment. Far-Western analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. A purified fragment of ERα from amino acids 39 to 160 (ERα39–160) was purified, and a fraction was phosphorylated in vitro with purified MAPK as described in the text. Blots of unphosphorylated (ERα39–160) and phosphorylated (pS118-ERα39–160) forms were transferred to a PVDF membrane following gel electrophoresis. The membrane was incubated with GST, GST-Pin1, or GST-Pin1 S16E (substrate binding Pin1 mutant) and probed for GST using anti-GST. Reprobing the blot for ERα showed equivalent loading.

Fig 4.

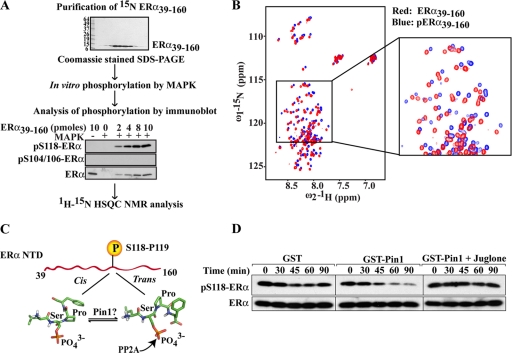

Pin1 induces isomerization around the pS118-P119 bond of ERα. (A) Flow chart of sample preparation for NMR spectroscopy. (Upper blot) Purity of ERα39–160 protein assessed in a Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel. (Lower blot) Various amounts of ERα39–160 were phosphorylated in vitro with purified MAPK as described in Materials and Methods. Phosphorylation of ERα was assessed by Western blot analysis using site-specific antibodies against phosphorylated S118 (pS118-ERα) and phosphorylated S104/106 (pS104/106-ERα). Western blot results for total ERα are shown in the bottom panel. (B) NMR analysis of unphosphorylated ERα39–160 and phosphorylated ERα39–160 (pERα39–160) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Shown is an overlay of the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra (600 MHz 1H), recorded at 25°C, of ERα39–160 (red) and pERα39–160 (blue). (C) Models representing cis and trans conformations of the pSer118-Pro119 bond. A schematic of the ERα NTD from amino acids 39 to 160 is shown on top and represents purified ERα39–160 as a disordered peptide. The stick model shows the phosphorylated pSer118-Pro119 bond in cis and trans conformations and potential catalysis by Pin1. PP2A selectively dephosphorylates the trans isomer and was used as a biochemical tool to assess cis and trans isomers of the pSer118-Pro119 bond of ERα. (D) An in vitro dephosphorylation assay was performed using S118 phosphorylated ERα39–160 and purified PP2A as described in Materials and Methods. Phosphorylated ERα39–160, in the presence of GST, GST-Pin1, or GST-Pin1 plus Juglone (Pin1 inhibitor), was treated with 100 ng PP2A for the indicated length of time. Western blot analysis was then performed for pS118-ERα and ERα. Shown is a representative Western blot of three independent experiments.

Pin1 induces cis-trans isomerization of the pS118-P119 bond of ERα AF1.

In contrast to the well-structured DBD and C-terminal domain (CTD), the N-terminal domain (NTD) of ERα is disordered, and little information exists regarding the impact of pS118 or phosphorylation in general on the ERα NTD (48). To begin to probe potential conformational regulation of ERα AF1 by Pin1, we first assessed the impact of S118 phosphorylation. A uniformly 15N-labeled ERα39–160 AF1 fragment was purified (Fig. 4A, upper blot) and in vitro phosphorylated using MAPK. These conditions resulted in selective phosphorylation of S118 but not S104 or S106 (Fig. 4A, lower blot), consistent with a previous report (51). 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR) spectra of nonphosphorylated [U-15N]ERα39–160 (red) and phosphorylated [U-15N]-ERα39–160 (pERα39–160) (blue) showed that although both spectra exhibited limited peak dispersion in the 1H dimension and remained disordered, phosphorylation led to significant changes in the positions of many peptide backbone cross peaks (Fig. 4B). These changes suggested that phosphorylation of S118 is associated with local as well as more extensive conformational changes within the AF1 domain.

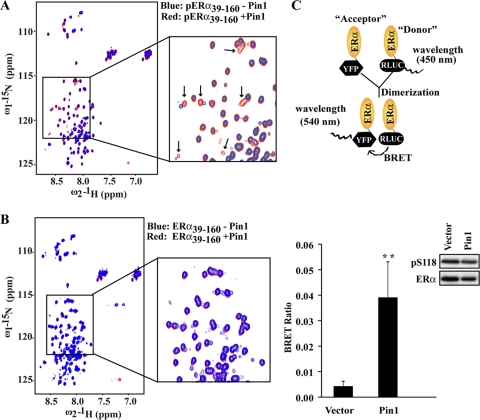

S/T-P motifs in a peptide bond, including S118, can exist in two conformations, cis or trans (Fig. 4C), but phosphorylation hinders the spontaneous isomerization of the prolyl bond by trapping the isomer predominantly in the cis conformation (81, 96, 100). As Pin1 can bind directly to the pS118-ERα39–160 fragment (Fig. 3H), it is plausible that Pin1 may isomerize the pS118-P119 bond of ERα39–160 AF1. To test this, we employed a dephosphorylation assay using PP2A, which preferentially dephosphorylates trans-Ser/Thr-Pro motifs and has been used as a tool to efficiently differentiate the isomeric status of Pin1 substrates (104) (Fig. 4C). Phosphorylated ERα39–160 fragment was coincubated with GST or GST-Pin1 in the presence of purified PP2A for various lengths of time, and the remaining amount of phosphorylated ERα was determined by Western blot analysis using pS118-ERα antibody. As shown in Fig. 4D, dephosphorylation of pS118-ERα39–160 occurred more rapidly in the presence of Pin1 than control GST. In addition, this dephosphorylation was inhibited by coincubation with Juglone, a Pin1 inhibitor (35) that has no effect on PP2A activity (28), indicating that Pin1 can directly accelerate isomerization of the pS118-P119 peptide bond of ERα from cis to trans. Indeed, NMR analysis following addition of a 10-fold molar excess of Pin1 led to small changes in the HSQC spectra of phosphorylated pERα39–160 (Fig. 5A), but not of unphosphorylated ERα39–160 (Fig. 5B), indicating a local phosphorylation-dependent conformational change.

Fig 5.

Pin1 induces NMR spectral changes in the pERα fragment and induces hormone-independent dimerization of ERα. (A and B) Overlay of 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra (600 MHz 1H), recorded at 25°C, of phosphorylated ERα39–160 (pERα39–160) alone (blue) or with excess Pin1 (red) (A) or unphosphorylated ERα39–160 (ERα39–160) alone (blue) or with excess Pin1 (red) (B). In panel A, the box encloses several cross peaks, indicated by arrows, that exhibited significant chemical shift changes upon Pin1 addition. (C) ERα dimerization was assessed in a BRET assay. (Upper panel) Cartoon representation of BRET assay results, with ERα molecules tagged with either “donor” Renilla luciferase (RLUC) or “acceptor” YFP. At close proximity, YFP emits light at the 540-nm wavelength. (Lower panel) BRET assays were carried out in HEK293 cells transiently expressing ER-RLUC and ERα-YFP that were transfected with vector or Flag-Pin1. The BRET ratio was calculated as described in Materials and Methods and includes correction for background random collision. The inset shows Western blot results for pS118-ERα and ERα. Data are presented as means ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. ∗∗, P < 0.01.

Since there was no structural information regarding how Pin1 might recognize pS118-P119 bond, we generated a computer model of this complex (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). The Pin1 structure was derived by removal of the Ala-Pro dipeptide, sulfate ion, and polyethylene glycol 400 molecules from the crystal structure by Ranganathan et al. (73) and modeled with the 4-amino-acid peptide of ERα (L117pS118P119F120; shown in green in the catalytic site of Pin1). Shown also are the amino acid side chains, such as K63, R68, and R69, of the PPIase domain of Pin1 (pink) surrounding the pS118-P119 ERα peptide. These interactions could orchestrate the catalysis of the pS118-P119 peptide bond rotation from cis (ω, 0°) to trans (ω, 180°) (73). Indeed, mutation of K63 to alanine abolished Pin1-mediated effects on AF1 activity (Fig. 2E). This model supports the notion that via a “tag-and-twist” mechanism proposed for Pin1 (55), a kinase tags (phosphorylates) the pS118-P119 motif, and Pin1 subsequently binds and twists (isomerizes) the pS118-P119 prolyl bond to introduce a kink or new conformation that could alter ERα AF1 function. The local conformational changes induced by proline isomerization in flexible domains have been shown to propagate to other regions of a protein, allosterically controlling their form and function (78, 79). To assess the possibility that Pin1-directed changes in the N terminus can be propagated to other ERα functional domains, a BRET assay was used that measured the energy transfer from activated Renilla luciferase to a YFP fused to the C termini of two separate ERα constructs (ERα-RLUC and ERα-YFP) under estrogen-deprived conditions (70) (Fig. 5C, upper panel). This assay has been used in previous studies to assess conformational changes associated with receptor dimerization (20, 45, 70) that can be mediated through the DNA and C-terminal ligand binding domains (10, 46, 82). Increased energy transfer (∼8-fold compared to vector) occurred upon overexpression of Pin1 (Fig. 5C, lower panel) in the absence of E2 and was abolished by S118 alanine substitution (see Fig. S3B), indicating that Pin1-induced changes, which originate in the N terminus of ERα, can induce subsequent modifications that increase the proximity of the C-terminal domains of two receptor monomers. These data demonstrate that phosphorylation-coupled events initiated in the AF1 region can be transmitted to other domains and promote downstream events, potentially receptor dimerization, that could increase transcriptional activation in the absence of ligand.

Pin1 promotes tamoxifen resistance in ERα-positive breast cancer cells.

Acquisition of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer can result from increased AF1 function (5, 63, 74). Since Pin1 increases AF1 transcriptional activity and was necessary for ERα+ breast cancer cell growth, Pin1 could be functionally coupled to tamoxifen resistance in ERα-dependent breast cancer cells. To test this possibility, we first evaluated whether Pin1 increased ERα activity in the presence of tamoxifen. Upon OHT (a potent tamoxifen metabolite) treatment, Pin1 increased the transcriptional activity of ERα by ∼3.5-fold over vector controls (Fig. 6A). Consistently, Pin1 also enhanced transcription in the absence of ligand (EtOH). The GST pulldown assay also indicated that Pin1 forms a complex with ERα in the presence of OHT, which is dependent on an intact S118 residue (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that similar to E2 and EGF, tamoxifen also induces recruitment of Pin1 to ERα transcriptional complexes in an S118-dependent (i.e., AF1-dependent) manner. Next, we asked if tamoxifen-dependent growth was susceptible to regulation by Pin1. Knockdown of Pin1 in MCF-7-5C cells, a tamoxifen-resistant derivative of MCF-7 cells (39), caused both a basal decrease (P = 0.053) and a significant inhibition in tamoxifen-induced growth during 24 and 48 h of OHT treatment (Fig. 6C) and, reciprocally, stable overexpression of Pin1 in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line resulted in increased growth in the presence of OHT compared to controls (Fig. 6D). Thus, tamoxifen can promote growth of breast cancer cells, at least in part by inducing recruitment of Pin1 to pS118-ERα, which in turn enhances AF1 activity.

Fig 6.

Contribution of Pin1 in tamoxifen resistance of breast cancer cells. (A) Reporter gene assays were carried out as described for Fig. 2A in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with wild-type ERα and vector or Pin1 along with ERE-tk-Luc and CMV–β-Gal. Cells were treated with EtOH or 0.1 μM OHT for 24 h. Relative luciferase levels were determined as the fold difference in luciferase/β-Gal activity relative to that in EtOH-treated vector control samples. (B) GST pulldown assays were performed using extracts from HEK293 cells stably expressing wild-type HA-ERα or HA-ERα S118A mutant that were treated with EtOH, 10 nM E2, or 0.1 μM OHT for 1 h. Extracts were incubated with GST or GST-Pin1, and Western blots (WB) were performed for HA. Input lanes show the presence of equal amounts of HA-ERα and HA ERα S118A proteins in extracts prior to pulldown. (C) Tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7-5C cells were transfected with Pin1 siRNA or control scr siRNA and treated with 1 μM OHT for the indicated length of time. Cell growth was measured using an MTT assay as described in Materials and Methods. Data are shown relative to those of the 0-h time point of scr siRNA-transfected cells. (D) MCF-7 cells overexpressing GFP-Pin1 or GFP were treated with 1 μM OHT for the indicated length of time. Cell growth was assessed spectrophotometrically using crystal violet staining. At harvest, cells were stained with 0.4% crystal violet solution, and following washing, cells were lysed in 50% methanol. Cell growth was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 540 nm of the resultant lysis solution. Data are shown relative to those of the 0-h time point for each cell. Data in all panels are presented as means ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

ERα's role in breast cancer biology is well-established. It is the single most important predictive biomarker for response to therapy, and it is the molecular target for the most commonly prescribed breast cancer therapeutics. ERα controls growth of breast cancer cells through the regulation of gene expression, and antagonization of ERα transcriptional function by interfering with ligand-dependent transcriptional activity (tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors) or degrading ERα protein forms the basis of current hormonal therapies. The regulatory events involved in ligand-dependent transcriptional activation of ERα via the AF2 domain have been extensively investigated (6, 38, 64, 68). While it was recognized early on that ERα transcriptional function involves both AF1 and AF2 (89), an understanding of the regulatory mechanisms governing AF1 have proven elusive. To fully control ERα activity in breast cancer, however, surely requires an understanding of the control of both the AF1 and AF2 domains. This study establishes a previously unrecognized mechanism by which phosphorylation controls AF1 activity. Our results show that phosphorylation of ERα at S118 induces chemical shifts that resonate throughout the AF1 domain and allows direct binding of Pin1 to ERα. Pin1 causes isomerization of the pS118-P119 bond, leading to additional local changes in chemical structure. Coordinately, Pin1 promotes dimerization of ERα and enhances receptor transcriptional function independently of a stimulus via AF1. Importantly, the increased AF1 transcriptional function of ERα conferred by Pin1 depends on the isomerization function, which is necessary to accelerate the conversion of the ERα AF1 domain from the cis to trans isomer, thereby coupling conformational reorganization to enhanced AF1 function. This enzyme-driven increase in AF1 activity could account in part for hormone-independent growth progression and tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells.

Our data indicate that Pin1 can act directly on ERα and modulate ERα activity. GST pulldown and far-Western analyses, as well as direct interaction of purified components, clearly indicate that Pin1 can form a complex with ERα that is dependent on pS118 in the absence of other factors. Reporter gene transcriptional assay results further support the conclusion that Pin1 catalytic activity acts specifically to control the AF1 but not the AF2 domain of ERα. However, Pin1 is a ubiquitously expressed protein that has several binding partners (97), and it cannot be excluded that the Pin1-mediated increase in ERα transactivation and growth of normal and tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells could be both direct and indirect (67, 97). Both estrogen and tamoxifen cause S118 phosphorylation in the AF1 domain, yet they also induce differential recruitment of coactivator and corepressors, respectively, to the AF2 domain (10, 84). The ERα-interacting factors amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) (101) and silencing mediator for retinoid or thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT) (85) also interact with Pin1 and could modulate ERα function. Yet, we observed that Pin1 was able to increase the transactivation potential of an ERα mutant (L540Q) which is compromised in coactivator interactions and does not bind AIB1 (1, 37). Nevertheless, our studies indicate that phosphorylation of S118 is necessary and sufficient for the Pin1 interaction with both estrogen and tamoxifen stimulation. Besides Pin1, S118 phosphorylation at the AF1 domain has been shown to recruit p68 RNA helicase and splicing factor SF3a p120, which act as AF1 coactivators, and SPBP, which behaves as a corepressor (25, 31, 62, 92). Although these pS118-dependent factors have not yet been determined as Pin1 substrates, it is tempting to speculate that the mechanism by which Pin1 enhances AF1 activity could be through direct actions on ERα and differential recruitment of these factors. Structural changes induced by Pin1 could create a stronger binding pocket for coactivator interaction, or such changes could alter the dynamics of the site inhibiting corepressor binding. Such Pin1-mediated changes in protein-protein interactions have been known to enhance transcription and protein stability of other proteins, including p53, p72, beta-catenin, and NF-κB (59, 76, 77, 98). Therefore, under different experimental conditions, and perhaps physiologic or pathological settings, distinct Pin-1-mediated mechanisms may predominate to control ERα activity.

One of the factors contributing to the general lack of understanding of ERα AF1 regulation is the lack of structural information of this domain. While the AF2 domain is located within the ligand binding domain and crystal structures exist for the CTD ligand-containing AF2 and DBD (82, 84), structural information on the AF1 domain is lacking. The ERα N terminus, including the AF1 domain, is unstructured but regulated through phosphorylation signaling (47, 48). Based on surface plasmon resonance and circular dichroism, Wärnmark et al. reported that the flexible ERα NTD is not resistant to structural changes and putatively can adopt an increase in order upon binding to the TATA box binding protein (TBP) (91). Gburcik et al. speculated that structural changes could be a mechanism controlling AF1 (32); however, the role of phosphorylation in the structural regulation of this region was unknown. To our knowledge, our NMR analyses of the N-terminal ERα39-160 fragment in different configurations (unphosphorylated, S118 phosphorylated, and S118 phosphorylated plus Pin1) provide the first insight into structural modulation within this “unstructured” domain upon covalent modification. Our NMR study showed that S118 phosphorylation alone (in the absence of Pin1 action) caused significant changes in the positions of many peptide backbone cross peaks in ERα39-160, suggesting that structural changes due to phosphorylation at a single site can propagate within the domain, leading to the global conformational changes of the otherwise-unstructured N terminus. This is not due to dimerization, since this domain cannot dimerize (46, 50, 87). Addition of purified recombinant Pin1 induced a further change, but the magnitudes of chemical shifts in this case were relatively small, indicative of a specifically localized change. This change could result from cis-to-trans isomerization of the pS118-P119 bond of the ERα fragment by Pin1, as shown in our in vitro PP2A assay. Given our biochemical analysis results, we propose a model in which the unphosphorylated ERα N terminus exists in equilibrium between the cis and trans conformers. Upon S118 phosphorylation, the ERα N terminus is preferentially held in the cis conformation, which is associated with a large-scale structural change within this domain. Upon Pin1 action on pS118-P119, the AF1 domain is subsequently altered to the trans conformation, involving a further but relatively modest local structural change. Additional NMR studies employing both double-labeled (13C and 15N) and larger segments of ERα will be helpful in further defining phosphorylation- and Pin1-directed structural changes. This is a plausible approach, as such structural changes upon Ser/Thr phosphorylation have been reported for other intrinsically disordered proteins (21, 72). Such studies, combined with additional analyses as demonstrated with our BRET results, will be useful in defining the role of N-terminal structural changes in modulating overall ERα structure and function.

The regulation of Pin1 at the N terminus may not be exclusive to ERα and may be conserved among other nuclear receptors. The N-terminal domains of several members of the nuclear steroid receptor family of transcription factors, such as PR, GR, AR, and ERβ, also contain putative Pin1 recognition motifs (75). The N termini of these receptors are otherwise unrelated; thus, the conservation of the Pin1 recognition motif in combination with the established ligand- and growth factor-induced phosphorylation of these sites strongly suggests that the Pin1 recognition may be functionally conserved among nuclear receptors. Indeed, Fujimoto et al. previously showed that an N-terminal S84P mutant of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a substrate for Pin1 (30). Similarly, Brondani et al. provided evidence that Pin1 interacted with the S77P motif of retinoid acid receptor alpha (RARα) (9). In the case of PPARγ, catalytic activity of Pin1 is dispensable for PPARγ regulation and negatively affects PPARγ transcriptional function, which is in contrast with our findings with ERα. Unique to our study is the direct assessment of the structural changes and cis-trans isomerization of a nuclear receptor NTD by Pin1. Despite the conservation of the S/T-P site in the NTD, the NTD itself is the least-conserved region among nuclear receptors, which could lead to differential regulation of receptor function by Pin1. However, our current study along with these previous studies on other nuclear receptors point to a phosphorylation-dependent isomerization by Pin1 as a general regulatory mechanism for the N-terminal domain of several nuclear steroid receptors.

Regulation of ERα phosphorylation is strongly linked to breast cancer progression but a “phosphorylation paradox” exists, wherein ERα S118 phosphorylation is associated with enhanced differentiation and slower cancer cell growth and yet also accelerates growth in the presence of antiestrogens (66, 80). Our data concur with several reports that phosphorylation at S118 is associated with increased growth in the presence of tamoxifen (8, 44, 51, 58). The biochemical data suggest a further modification beyond phosphorylation (i.e., isomerization) that could influence the outcome. Although our analyses are limited to an ERα fragment due to the size limitations of NMR analysis, the data bring forth an intriguing possibility that phosphorylated ERα exists in two configurations (cis and trans). Under the regulation of Pin1, the equilibrium shifts toward the trans conformation of pS118ERα, which is accompanied by increased transcriptional activity, presenting the possibility that the trans configuration preferentially places AF1 in a more active state. Recognition of the existence of multiple isoforms of ERα (ERα, cis-pERα, and trans-pERα) with distinct properties and functions has implications relevant to the interpretation of phosphorylated ERα as a therapeutic target and biomarker, and it advances Pin1 as a significant contributing factor that could explain some of the controversies that exist with regard to the relationship between ERα phosphorylation and clinical outcome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the McArdle Laboratories for Cancer Research for support of this project. We also thank the UW Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center (UWCCC) for use of its shared services to complete this research. Protein samples used in our NMR studies were produced by the Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics (CESG) with support from NIH grant U54 GM074901 (to J.L.M.). NMR data were collected at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility (Madison), which is supported by NIH grants P41 RR02301 and P41 GM66326 (to J.L.M.). This work was also supported by NIH grants CA159578 (to E.T.A.), T32 GM08688 (to P.R.), and R01 GM56230 (to K.P.L.) and in part by NIH/NCI P30 CA014520-UWCCC support. In vivo studies were supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under W81XWH-07-1-0502 (to S.Z.H.) and by NIH Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers grant U01 ES/CA012800 (to S.Z.H.).

We thank the CESG staff members who contributed to preparing protein samples used in ou-NMR studies. We thank Zafar Nawaz, Jing Zhang, Benita Katzenellenbogen, Edwin Sanchez, Yongna Xing, and Wei Xu for appropriate expression plasmids and purified protein and Shigeki Miyamoto and Wei Xu for careful reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 November 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Acevedo ML, Lee KC, Stender JD, Katzenellenbogen BS, Kraus WL. 2004. Selective recognition of distinct classes of coactivators by a ligand-inducible activation domain. Mol. Cell 13:725–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ali S, Metzger D, Bornert JM, Chambon P. 1993. Modulation of transcriptional activation by ligand-dependent phosphorylation of the human oestrogen receptor A/B region. EMBO J. 12:1153–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atsriku C, et al. 2009. Systematic mapping of posttranslational modifications in human estrogen receptor-alpha with emphasis on novel phosphorylation sites. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8:467–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartels C, Xia T-H, Billeter M, Güntert P, Wüthrich K. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 6:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berry M, Metzger D, Chambon P. 1990. Role of the two activating domains of the oestrogen receptor in the cell-type and promoter-context dependent agonistic activity of the anti-oestrogen 4-hydroxytamoxifen. EMBO J. 9:2811–2818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bocchinfuso WP, Korach KS. 1997. Estrogen receptor residues required for stereospecific ligand recognition and activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 11:587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borras M, et al. 1996. Estrogenic and anti-estrogenic regulation of half-life of covalently labeled estrogen receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 57:203–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Britton DJ, et al. 2006. Bidirectional cross talk between ERα and EGFR signalling pathways regulates tamoxifen-resistant growth. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 96:131–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brondani V, Schefer Q, Hamy F, Klimkait T. 2005. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates phospho-Ser77 retinoic acid receptor alpha stability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328:6–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brzozowski AM, et al. 1997. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature 389:753–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bunone G, Briand PA, Miksicek RJ, Picard D. 1996. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J. 15:2174–2183 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calligé M, Kieffer I, Richard-Foy H. 2005. CSN5/Jab1 is involved in ligand-dependent degradation of estrogen receptorα by the proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:4349–4358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Castles CG, Oesterreich S, Hansen R, Fuqua SA. 1997. Auto-regulation of the estrogen receptor promoter. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 62:155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen D, et al. 2000. Activation of estrogen receptor alpha by S118 phosphorylation involves a ligand-dependent interaction with TFIIH and participation of CDK7. Mol. Cell 6:127–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheng J, Zhang C, Shapiro DJ. 2007. A functional serine 118 phosphorylation site in estrogen receptor-alpha is required for down-regulation of gene expression by 17β-estradiol and 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Endocrinology 148:4634–4641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clarke RB, Howell A, Potten CS, Anderson E. 1997. Dissociation between steroid receptor expression and cell proliferation in the human breast. Cancer Res. 57:4987–4991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Couse JF, Korach KS. 1999. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr. Rev. 20:358–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delaglio F, et al. 1995. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6:277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dowsett M, et al. 2010. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J. Clin. Oncol. 28:509–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duplessis TT, Koterba KL, Rowan BG. 2009. Detection of ERα-SRC-1 interactions using bioluminescent resonance energy transfer. Methods Mol. Biol. 590:253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a. Duplessis TT, Williams CC, Hill SM, Rowan BG. 2011. Phosphorylation of estrogen receptor alpha at serine 118 directs recruitment of promoter complexes and gene-specific transcription. Endocrinology 152:2517–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dyson HJ, Wright PE. 2005. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group 2005. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365:1687–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Einarson MB, Pugacheva EN, Orlinick JR. 2007. Far Western: probing membranes. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2007. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot4759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ellison-Zelski SJ, Solodin NM, Alarid ET. 2009. Repression of ESR1 through actions of estrogen receptor alpha and Sin3A at the proximal promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:4949–4958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Endoh H, et al. 1999. Purification and identification of p68 RNA helicase acting as a transcriptional coactivator specific for the activation function 1 of human estrogen receptor alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5363–5372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26. Fabris G, et al. 1987. Pathophysiology of estrogen receptors in mammary tissue by monoclonal antibodies. J. Steroid Biochem. 27:171–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Faus H, Haendler B. 2006. Post-translational modifications of steroid receptors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 60:520–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fila C, Metz C, van der Sluijs P. 2008. Juglone inactivates cysteine-rich proteins required for progression through mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:21714–21724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fowler AM, et al. 2004. Increases in estrogen receptor-alpha concentration in breast cancer cells promote serine 118/104/106-independent AF-1 transactivation and growth in the absence of estrogen. FASEB J. 18:81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujimoto Y, et al. 2010. Proline cis/trans-isomerase Pin1 regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activity through the direct binding to the activation function-1 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 285:3126–3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gburcik V, Bot N, Maggiolini M, Picard D. 2005. SPBP is a phosphoserine-specific repressor of estrogen receptor alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:3421–3430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gburcik V, Picard D. 2006. The cell-specific activity of the estrogen receptor alpha may be fine-tuned by phosphorylation-induced structural gymnastics. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 4:e005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gutierrez MC, et al. 2005. Molecular changes in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: relationship between estrogen receptor, HER-2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Clin. Oncol. 23:2469–2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heldring N, et al. 2007. Structural insights into corepressor recognition by antagonist-bound estrogen receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 282:10449–10455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hennig L, et al. 1998. Selective inactivation of parvulin-like peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases by juglone. Biochemistry 37:5953–5960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Henrich LM, et al. 2003. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 7, a regulator of hormone-dependent estrogen receptor destruction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5979–5988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ince BA, Zhuang Y, Wrenn CK, Shapiro DJ, Katzenellenbogen BS. 1993. Powerful dominant negative mutants of the human estrogen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14026–14032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jenster G, et al. 1997. Steroid receptor induction of gene transcription: a two-step model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:7879–7884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiang SY, Wolf DM, Yingling JM, Chang C, Jordan VC. 1992. An estrogen receptor positive MCF-7 clone that is resistant to antiestrogens and estradiol. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 90:77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kariagina A, Aupperlee MD, Haslam SZ. 2007. Progesterone receptor isoforms and proliferation in the rat mammary gland during development. Endocrinology 148:2723–2736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kariagina A, Xie J, Leipprandt JR, Halsam SZ. 2010. Amphiregulin mediates estrogen, progesterone, and EGFR signaling in the normal rat mammary gland and in hormone-dependent rat mammary cancers. Hormones Cancer 1:229–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kato S, et al. 1995. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science 270:1491–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kay L, Keifer P, Saarinen T. 1992. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:10663–10665 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Knowlden JM, et al. 2003. Elevated levels of epidermal growth factor receptor/c-erbB2 heterodimers mediate an autocrine growth regulatory pathway in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells. Endocrinology 144:1032–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koterba KL, Rowan BG. 2006. Measuring ligand-dependent and ligand-independent interactions between nuclear receptors and associated proteins using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). Nucl. Recept. Signal. 4:e021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kumar V, Chambon P. 1988. The estrogen receptor binds tightly to its responsive element as a ligand-induced homodimer. Cell 55:145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lannigan DA. 2003. Estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Steroids 68:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lavery DN, McEwan IJ. 2005. Structure and function of steroid receptor AF1 transactivation domains: induction of active conformations. Biochem. J. 391:449–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Le Goff P, Montano MM, Schodin DJ, Katzenellenbogen BS. 1994. Phosphorylation of the human estrogen receptor. Identification of hormone-regulated sites and examination of their influence on transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 269:4458–4466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lees JA, Fawell SE, White R, Parker MG. 1990. A 22-amino-acid peptide restores DNA-binding activity to dimerization-defective mutants of the estrogen receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5529–5531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Likhite VS, Stossi F, Kim K, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. 2006. Kinase-specific phosphorylation of the estrogen receptor changes receptor interactions with ligand, deoxyribonucleic acid, and coregulators associated with alterations in estrogen and tamoxifen activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 20:3120–3132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lim J, et al. 2008. Pin1 has opposite effects on wild-type and P301L tau stability and tauopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 118:1877–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lu KP, Finn G, Lee TH, Nicholson LK. 2007. Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lu KP, Hanes SD, Hunter T. 1996. A human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase essential for regulation of mitosis. Nature 380:544–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu KP, Liou YC, Zhou XZ. 2002. Pinning down proline-directed phosphorylation signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 12:164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lu KP, Zhou XZ. 2007. The prolyl isomerase PIN1: a pivotal new twist in phosphorylation signalling and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:904–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lu PJ, Wulf G, Zhou XZ, Davies P, Lu KP. 1999. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 restores the function of Alzheimer-associated phosphorylated tau protein. Nature 399:784–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lykkesfeldt AE, Madsen MW, Briand P. 1994. Altered expression of estrogen-regulated genes in a tamoxifen-resistant and ICI 164,384 and ICI 182,780 sensitive human breast cancer cell line, MCF-7/TAMR-1. Cancer Res. 54:1587–1595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mantovani F, et al. 2004. Pin1 links the activities of c-Abl and p300 in regulating p73 function. Mol. Cell 14:625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Markley JL, et al. 2009. The Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 10:165–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marsaud V, Gougelet A, Maillard S, Renoir J-M. 2003. Various phosphorylation pathways, depending on agonist and antagonist binding to endogenous estrogen receptor α (ERα) differentially affect ERα extractability, proteasome-mediated stability, and transcriptional activity in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 17:2013–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Masuhiro Y, et al. 2005. Splicing potentiation by growth factor signals via estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:8126–8131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McInerney EM, Katzenellenbogen BS. 1996. Different regions in activation function-1 of the human estrogen receptor required for antiestrogen- and estradiol-dependent transcription activation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24172–24178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW. 1999. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr. Rev. 20:321–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Medunjanin S, et al. 2005. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 interacts with and phosphorylates estrogen receptor alpha and is involved in the regulation of receptor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33006–33014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Murphy LC, Seekallu SV, Watson PH. 2011. Clinical significance of estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18:R1–R14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Namgoong GM, et al. 2010. The prolyl-isomerase Pin1 induces LC-3 expression and mediates tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 285:23829–23841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pakdel F, Reese JC, Katzenellenbogen BS. 1993. Identification of charged residues in an N-terminal portion of the hormone-binding domain of the human estrogen receptor important in transcriptional activity of the receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 7:1408–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pons M, Gagne D, Nicolas JC, Mehtali M. 1990. A new cellular model of response to estrogens: a bioluminescent test to characterize (anti) estrogen molecules. Biotechniques 9:450–459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Powell E, Xu W. 2008. Intermolecular interactions identify ligand-selective activity of estrogen receptor alpha/beta dimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19012–19017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Powers GL, Ellison-Zelski SJ, Casa AJ, Lee AV, Alarid ET. 2010. Proteasome inhibition represses ERα gene expression in ER+ cells: a new link between proteasome activity and estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Oncogene 29:1509–1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ramelot TA, Nicholson LK. 2001. Phosphorylation-induced structural changes in the amyloid precursor protein cytoplasmic tail detected by NMR. J. Mol. Biol. 307:871–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ranganathan R, Lu KP, Hunter T, Noel JP. 1997. Structural and functional analysis of the mitotic rotamase Pin1 suggests substrate recognition is phosphorylation dependent. Cell 89:875–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ring A, Dowsett M. 2004. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 11:643–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rochette-Egly C. 2003. Nuclear receptors: integration of multiple signalling pathways through phosphorylation. Cell. Signal. 15:355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ryo A, Nakamura M, Wulf G, Liou YC, Lu KP. 2001. Pin1 regulates turnover and subcellular localization of beta-catenin by inhibiting its interaction with APC. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ryo A, et al. 2003. Regulation of NF-κB signaling by Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p65/RelA. Mol. Cell 12:1413–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sarkar P, Reichman C, Saleh T, Birge RB, Kalodimos CG. 2007. Proline cis-trans isomerization controls autoinhibition of a signaling protein. Mol. Cell 25:413–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sarkar P, Saleh T, Tzeng SR, Birge RB, Kalodimos CG. 2011. Structural basis for regulation of the Crk signaling protein by a proline switch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7:51–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sarwar N, et al. 2006. Phosphorylation of ERα at serine 118 in primary breast cancer and in tamoxifen-resistant tumours is indicative of a complex role for ERα phosphorylation in breast cancer progression. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 13:851–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Schutkowski M, et al. 1998. Role of phosphorylation in determining the backbone dynamics of the serine/threonine-proline motif and Pin1 substrate recognition. Biochemistry 37:5566–5575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schwabe JW, Chapman L, Finch JT, Rhodes D. 1993. The crystal structure of the estrogen receptor DNA-binding domain bound to DNA: how receptors discriminate between their response elements. Cell 75:567–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shaaban AM, Sloane JP, West CR, Foster CS. 2002. Breast cancer risk in usual ductal hyperplasia is defined by estrogen receptor-alpha and Ki-67 expression. Am. J. Pathol. 160:597–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shiau AK, et al. 1998. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell 95:927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Stanya KJ, Liu Y, Means AR, Kao HY. 2008. Cdk2 and Pin1 negatively regulate the transcriptional corepressor SMRT. J. Cell Biol. 183:49–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Suizu F, Ryo A, Wulf G, Lim J, Lu KP. 2006. Pin1 regulates centrosome duplication, and its overexpression induces centrosome amplification, chromosome instability, and oncogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:1463–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tamrazi A, Carlson KE, Daniels JR, Hurth KM, Katzenellenbogen JA. 2002. Estrogen receptor dimerization: ligand binding regulates dimer affinity and dimer dissociation rate. Mol. Endocrinol. 16:2706–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tan X, et al. 2010. Pin1 expression contributes to lung cancer: prognosis and carcinogenesis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 9:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tora L, et al. 1989. The human estrogen receptor has two independent nonacidic transcriptional activation functions. Cell 59:477–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Valley CC, et al. 2005. Differential regulation of estrogen-inducible proteolysis and transcription by the estrogen receptor alpha N terminus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:5417–5428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Warnmark A, Wikstrom A, Wright AP, Gustafsson JA, Hard T. 2001. The N-terminal regions of estrogen receptor alpha and beta are unstructured in vitro and show different TBP binding properties. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45939–45944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Watanabe M, et al. 2001. A subfamily of RNA-binding DEAD-box proteins acts as an estrogen receptor alpha coactivator through the N-terminal activation domain (AF-1) with an RNA coactivator, SRA. EMBO J. 20:1341–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 93. Watters JJ, Campbell JS, Cunningham MJ, Krebs EG, Dorsa DM. 1997. Rapid membrane effects of steroids in neuroblastoma cells: effects of estrogen on mitogen activated protein kinase signalling cascade and c-fos immediate early gene transcription. Endocrinology 138:4030–4033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Weigel NL, Moore NL. 2007. Steroid receptor phosphorylation: a key modulator of multiple receptor functions. Mol. Endocrinol. 21:2311–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Weigel NL, Zhang Y. 1998. Ligand-independent activation of steroid hormone receptors. J. Mol. Med. 76:469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]