Abstract

While picornaviruses are known to infect different animals, their existence in the domestic cat was unknown. We describe the discovery of a novel feline picornavirus (FePV) from stray cats in Hong Kong. From samples from 662 cats, FePV was detected in fecal samples from 14 cats and urine samples from 2 cats by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Analysis of five FePV genomes revealed a distinct phylogenetic position and genomic features, with low sequence homologies to known picornaviruses especially in leader and 2A proteins. Among the viruses that belong to the closely related bat picornavirus groups 1 to 3 and the genus Sapelovirus, G+C content and sequence analysis of P1, P2, and P3 regions showed that FePV is most closely related to bat picornavirus group 3. However, FePV possessed other distinct features, including a putative type IV internal ribosome entry site/segment (IRES) instead of type I IRES in bat picornavirus group 3, protein cleavage sites, and H-D-C catalytic triad in 3Cpro different from those in sapeloviruses and bat picornaviruses, and the shortest leader protein among known picornaviruses. These results suggest that FePV may belong to a new genus in the family Picornaviridae. Western blot analysis using recombinant FePV VP1 polypeptide showed a high seroprevalence of 33.6% for IgG among the plasma samples from 232 cats tested. IgM was also detected in three cats positive for FePV in fecal samples, supporting recent infection in these cats. Further studies are important to understand the pathogenicity, epidemiology, and genetic evolution of FePV in these common pet animals.

INTRODUCTION

Picornaviruses are widely distributed in humans and other animals in which they can cause respiratory, cardiac, hepatic, neurological, mucocutaneous, and systemic diseases with different degrees of severity (53). Picornaviruses are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses with icosahedral capsids. Based on genotypic and serological characterization, the family Picornaviridae is currently divided into 12 genera, namely, Enterovirus, Cardiovirus, Aphthovirus, Hepatovirus, Parechovirus, Erbovirus, Kobuvirus, Teschovirus, Sapelovirus, Senecavirus, Tremovirus, and Avihepatovirus. Since the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, there has been an increase in the interest in studying novel zoonotic viruses including picornaviruses (6, 10, 30, 31, 39, 40, 57–59). Novel human picornaviruses including the novel rhinovirus species, human rhinovirus C, have also been discovered in the past few years (11, 27, 37, 38, 44). Recently, we have described the discovery of novel picornaviruses from wild dead birds (proposed species turdiviruses 1, 2, and 3) as well as bats of diverse species (bat picornavirus groups 1 to 3) in Hong Kong (35, 60). The identification of novel picornaviruses and previously unknown animal hosts, such as bats, for these viruses is important for better understanding of their genetic diversity, evolution, biology, and potential for cross species transmission and emergence.

Cats are the most popular pet in the world. Viruses belonging to at least 14 families including rabies virus are known to infect these animals, which live closely with humans. However, the role and presence of picornaviruses in cats have been largely unknown. We hypothesized that previously unrecognized picornaviruses may be present in cats. In this article, we described a territory-wide molecular epidemiological study and the discovery of a novel picornavirus, feline picornavirus (FePV), in stray cats from Hong Kong. Comparative genome analysis showed that this virus belonged to a distinct cluster among known members in the Picornaviridae family, with distinct genomic and protein features. The virus was detected in 2.1% of fecal samples from cats included in this study, with a seroprevalence of 33.6% for IgG by Western blot analysis. On the basis of our results, we propose that FePV is a novel virus species, which may belong to a novel genus in the Picornaviridae family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cat surveillance and sample collection.

Samples from 662 stray cats, captured at 32 different locations in Hong Kong during a 39-month period (July 2007 to May 2011), were provided by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation (AFCD), a department under the government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), as part of a surveillance program for stray cats. Nasopharyngeal, fecal, urine, and blood samples were collected from the stray cats by the Animal Management Centres, AFCD, using procedures described previously (34, 39). All samples were collected immediately after euthanasia as routine policies for disposal of locally captured stray cats.

RNA extraction.

Viral RNA was extracted from the nasopharyngeal swabs, fecal swabs, and urine samples using a viral RNA minikit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany) and from blood samples using a QIAamp RNA blood minikit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA was eluted in 60 μl of RNase-free water and was used as the template for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

RT-PCR of 3Dpol gene of picornaviruses using conserved primers and DNA sequencing.

Initial picornavirus screening was performed by amplifying a 125-bp fragment of the 3Dpol gene of picornaviruses using conserved primers (5′-GTGGGCTGCAAYCCNGA-3′ and 5′-TTNAGNGCATCAAACCARA-3′) designed by multiple-sequence alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the 3Dpol genes of various picornaviruses using previously described protocols (35, 60, 63). Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), and the reaction mixture (10 μl) contained RNA, first-strand buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 ng random hexamers, 500 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 100 U SuperScript III reverse transcriptase. The mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 5 min, followed by 50°C for 60 min and 70°C for 15 min. The PCR mixture (25 μl) contained cDNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% gelatin), 200 μM (each) dNTPs, and 1.0 U Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The mixtures were amplified in 40 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min in an automated thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Standard precautions were taken to avoid PCR contamination, and no false-positive results was observed for the negative controls.

All PCR products were gel purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). Both strands of the PCR products were sequenced twice with an ABI Prism 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using the two PCR primers. The sequences of the PCR products were compared with known sequences of the 3Dpol genes of picornaviruses in the GenBank database.

RT-PCR of the 2C gene of the novel feline picornavirus using specific primers and DNA sequencing.

As initial RT-PCR of the 3Dpol gene revealed a potential novel picornavirus in one fecal sample, all the fecal samples were subjected to RT-PCR for FePV, using primers (5′-CAAGCTCTTCTGTCAGATGGT-3′ and 5′-GCAACATCTCTTGAAGTTGGT-3′) designed using the nucleotide sequence obtained during genome sequencing by amplifying a 283-bp fragment of the 2C gene. The respiratory, urine, and blood samples from cats with fecal samples positive for FePV were also subjected to RT-PCR. The components of the PCR mixtures and the cycling conditions were the same as those described above. Purification of the PCR products and DNA sequencing were performed as described above, using the corresponding PCR primers. The sequences of the PCR products were compared with known sequences of the 2C genes of picornaviruses in the GenBank database.

Genome sequencing.

Five genomes of FePV were amplified and sequenced using strategies we previously used for complete genome sequencing of other picornaviruses with the RNA extracted from the fecal samples as templates (35, 60, 63). The RNA was converted to cDNA by a combined random-priming and oligo(dT) priming strategy. As initial results showed that FePV was most closely related to our recently described bat picornaviruses and the sapeloviruses, the cDNA was amplified by degenerate primers designed by multiple-sequence alignment of the genomes of these viruses (GenBank accession nos. HQ595340 to HQ595345, NC_003987, NC_004451, and NC_006553), and additional primers designed from the results of the first and subsequent rounds of sequencing. These primer sequences are available on request. The 5′ ends of the viral genomes were confirmed by rapid amplification of cDNA ends using the SMARTer rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) cDNA amplification kit (Clontech). Sequences were assembled to produce the final sequences of the viral genomes.

Genome analysis.

The nucleotide sequences of the genomes and the deduced amino acid sequences of the open reading frame were compared to those of other picornaviruses. The unrooted phylogenetic trees of 2C and 3Dpol fragments and complete VP1 gene were constructed using the neighbor-joining method for aligned nucleotide sequences in ClustalX 2.1. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees of P1, P2 (excluding 2A), and P3 (excluding 3A) were constructed using the PhyML 3.0 program (20), with bootstrap values calculated from 100 trees. Secondary structure prediction in the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) was performed using Mfold (64).

Estimation of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates.

The number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site, Ks, and the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site, Ka, for each coding region in the five strains of FePV were calculated by the Kumar method in the MEGA 4 software program (51).

Cloning and purification of His6-tagged recombinant FePV VP1 polypeptide.

Since the VP1 protein is the largest and most surface-exposed protein and contains most of the motifs important for interaction with neutralizing antibodies and cellular receptors in picornaviruses (46), recombinant VP1 polypeptide of FePV was cloned and purified according to previously described strategies (14, 36, 39). To produce a fusion plasmid for protein purification, primers 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGGACTGGGTGATGACCTCTCT-3′ and 5′-GGAATTCCATATGCTAAGTCCCGATCTCCATAGGGT-3′ were used to amplify the VP1 gene of FePV by RT-PCR. The sequence coding for a total of 305 amino acid residues were amplified and cloned into the NdeI site of expression vector pET-28b(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI) in frame and downstream of the series of six histidine residues. The His6-tagged recombinant VP1 polypeptide was expressed and purified using the Ni2+-loaded HiTrap chelating system (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis.

To determine the seroprevalence of FePV, Western blot analysis, using purified FePV VP1 polypeptide and plasma samples from stray cats, were performed as described previously (36, 39). Briefly, 600 ng of purified His6-tagged recombinant VP1 polypeptide of FePV was loaded into each well of a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gel and subsequently electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The blot was cut into strips, and the strips were incubated separately with 1:500 and 1:200 dilutions of plasma samples collected from stray cats with plasma samples available for IgM and IgG detection, respectively. Antigen-antibody interaction was detected with 1:10,000 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-cat IgM and 1:4,000 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-cat IgG heavy and light chains (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX) and ECL fluorescence system (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Viral culture.

Five fecal samples and one urine sample positive for FePV were cultured in Vero E6 (African green monkey kidney; ATCC CRL-1586), CrFK (Crandell feline kidney; ATCC CCL-94), HFL (human embryonic lung fibroblast), and NIH 3T3 (mouse embryonic fibroblast, ATCC CRL-1658) cells.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the genomes of five FePV strains have been deposited in the GenBank sequence database under accession nos. JN572115 to JN572119. The nucleotide sequences of part of the 2C region of nine FePV strains have been deposited in GenBank under accession nos. JN848817 to JN848827.

RESULTS

Cat surveillance and identification of a novel feline picornavirus.

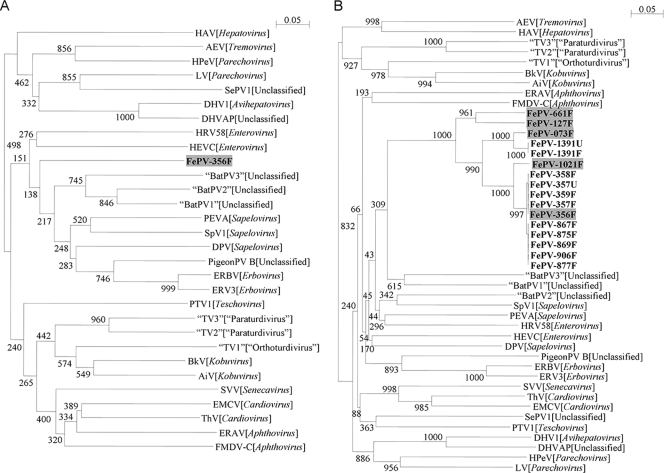

A total of 834 respiratory, fecal, urine, and blood samples from 662 stray cats were obtained. Initial screening of respiratory, fecal, urine, and blood samples from 48 stray cats by RT-PCR for a 125-bp fragment in the 3Dpol gene of picornavirus was positive in one fecal sample. The sequence from this positive sample had <65% nucleotide identity to the corresponding parts of the 3Dpol genes in all other known picornaviruses, suggesting the presence of a novel feline picornavirus (Fig. 1A). Subsequent specific RT-PCR for the 2C gene of the novel feline picornavirus on 662 fecal samples was positive in 14 (2.1%) samples. The sequences from these 14 samples had <64% nucleotide identities to the corresponding parts of the 2C genes in all other known picornaviruses. Moreover, these sequences fell into a distinct cluster, representing a novel picornavirus, FePV (Fig. 1B). RT-PCR for FePV was positive in two urine samples from 2 of the 14 cats with FePV detected in their fecal samples. The sequences from urine and fecal samples from the same cat were identical, suggestive of a single strain of FePV. All respiratory and blood samples from these 14 cats were negative for FePV by RT-PCR. FePV was detected mainly from spring to autumn (during March, May, June, August, and October) during the study period.

Fig 1.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences of the 89-bp fragment (excluding primer sequences) of the 3Dpol gene of a picornavirus identified from a cat (shaded in gray). (B) Phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences of the 241-bp fragment (excluding primer sequences) of the 2C gene of the novel picornavirus, FePV, identified from 14 fecal samples and two urine samples from 14 cats in the present study. The strain names have the letter F for fecal sample or the letter U for urine sample at the end of the strain name. The novel picornavirus strains are shown in boldface type. The five strains with genomes completely sequenced are shaded in gray. The trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method, and bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 trees. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 20 nucleotides. Virus abbreviations (GenBank accession numbers shown in parentheses): AEV, avian encephalomyelitis virus (NC_003990); AiV, Aichi virus (NC_001918); “BatPV1,” bat picornavirus 1 (HQ595340); “BatPV2,” bat picornavirus 2 (HQ595342); “BatPV3,” bat picornavirus 3 (HQ595344); BkV, bovine kobuvirus (NC_004421); DHV1, duck hepatitis virus 1 (NC_008250); DHVAP, duck hepatitis virus AP (NC_009750); DPV, avian sapelovirus (NC_006553); EMCV, encephalomyocarditis virus (NC_001479); ERAV, equine rhinitis A virus (NC_003982); ERBV, equine rhinitis B virus 1 (NC_003983); ERV3, equine rhinovirus 3 (NC_003077); FMDV-C, foot-and-mouth disease virus type C (NC_002554); HAV, hepatitis A virus (NC_001489); HEVC, human enterovirus C (NC_002058); HRV58, human rhinovirus 58 (FJ445142); HPeV, human parechovirus (NC_001897); LV, Ljungan virus (NC_003976); PEVA, porcine sapelovirus (NC_003987); PigeonPV B, pigeon picornavirus B (NC_015626); PTV1, porcine teschovirus 1 (NC_003985); SePV1, seal picornavirus type 1 (NC_009891); SVV, Seneca Valley virus (NC_011349); SpV1, simian sapelovirus (NC_004451); ThV, theilovirus (NC_001366); “TV1,” turdivirus 1 (NC_014411); “TV2,” turdivirus 2 (NC_014412); “TV3,” turdivirus 3 (NC_014413).

Genome organization and coding potential of FePV.

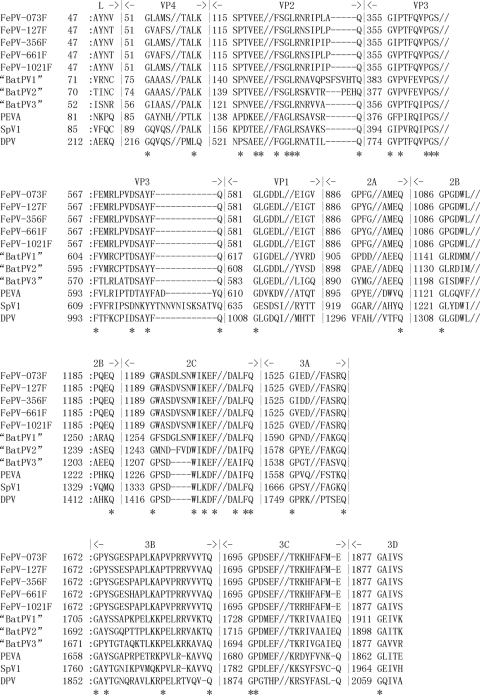

The genomes of the five FePV strains were 7,390 to 7,433 bases long, after excluding the polyadenylated tract, and the G+C content was 50.2 to 51.2%. The genome sizes of some strains may be larger, as further sequencing of the ends may have been hampered by secondary structures. Their genome organizations are similar to those of other picornaviruses, with the characteristic gene order 5′-L, VP4, VP2, VP3, VP1, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3Cpro, 3Dpol-3′. Both the 5′ ends (299 to 323 bases) and 3′ ends (77 to 103 bases) of the genomes contain untranslated regions (UTRs). Downstream of the leader protein (L), each genome contains a large open reading frame of 7,014 bases, which encodes potential polyprotein precursors of 2,337 amino acids (aa). The hypothetical protease cleavage sites of the polyproteins, as determined by multiple-sequence alignments with other picornaviruses with complete genomes available, are shown in Fig. 2. While most of the cleavage sites were similar to those of the sapeloviruses and bat picornavirus groups 1 to 3, FePV possessed distinct amino acid residues at certain cleavage sites at the junctions of L and VP4, VP1 and 2A, and 3C and 3D proteins (see below).

Fig 2.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the polyproteins of FePV compared with those of closely related picornaviruses including bat picornavirus groups 1 to 3 and sapeloviruses. Gaps introduced to maximize alignment are indicated by dashes. Conserved amino acids are indicated by an asterisk below the sequence alignment.

Phylogenetic analyses.

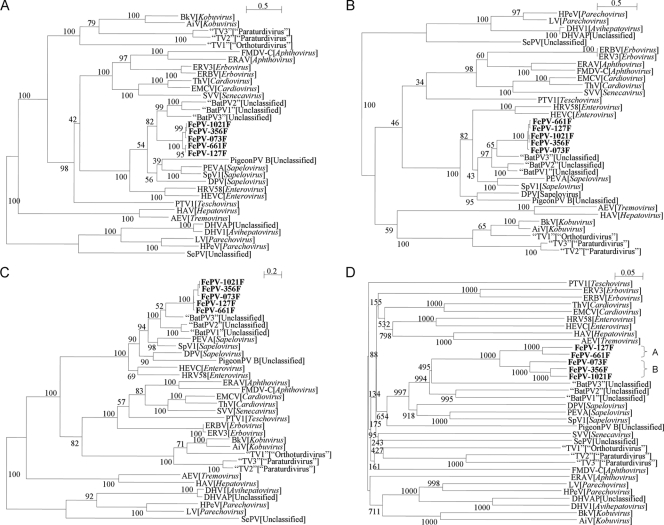

The phylogenetic trees constructed using the amino acid sequences of P1, P2 (excluding 2A), and P3 (excluding 3A) of FePV and other picornaviruses are shown in Fig. 3, and the corresponding pairwise amino acid identities are shown in Table 1. The 2A and 3A regions were excluded to avoid bias due to poor sequence alignment. For all three regions, FePV possessed higher amino acid identities to the corresponding regions or genes of bat picornaviruses, especially group 3 bat picornavirus, than to those of other picornaviruses (Table 1). In all three trees, the five FePV strains formed a distinct cluster among the known picornaviruses with very high bootstrap support, although they were most closely related to the bat picornaviruses than to other picornaviruses (Fig. 3). Further phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 sequences showed two distinct clusters of sequences, one formed by two strains, 127F and 661F, and the other formed by three strains, 073F, 356F and 1021F, suggesting the presence of two different genotypes of FePV, genotypes A and B, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

(A to D) Phylogenetic analyses of the P1 (A), P2 (excluding 2A) (B), P3 (excluding 3A) (C), and VP1 (D) regions of five strains of FePV (shown in boldface type). The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 2 (P1 and P2) and 5 (P3) amino acids and 20 nucleotides (VP1), respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of genomic features of FePV and representative species of other picornavirus genera and amino acid identities between the predicted proteins P1, P2, P3, 3Cpro, and 3Dpol proteins of FePV and the corresponding proteins of representative species of other picornavirus genera

| Picornavirus genus | Picornavirus species | GenBank accession no. | Genome feature |

Pairwise amino acid identity (%) of feline picornavirus (356F) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bases) | G+C content | P1 | P2a | P3b | 3Cpro | 3Dpol | |||

| Aphthovirus | Foot-and-mouth disease virus C | NC_002554 | 8,115 | 0.54 | 25.4 | 26.0 | 28.3 | 22.9 | 30.9 |

| Avihepatovirus | Duck hepatitis virus 1 | NC_008250 | 7,687 | 0.43 | 19.5 | 24.2 | 26.9 | 22.6 | 29.0 |

| Cardiovirus | Encephalomyocarditis virus | NC_001479 | 7,835 | 0.49 | 28.9 | 27.1 | 28.4 | 19.5 | 32.1 |

| Enterovirus | Human enterovirus C | NC_002058 | 7,440 | 0.46 | 37.0 | 38.2 | 49.3 | 38.3 | 54.1 |

| Erbovirus | Equine rhinovirus 3 | NC_003077 | 8,821 | 0.50 | 27.1 | 23.6 | 28.6 | 20.0 | 33.5 |

| Hepatovirus | Hepatitis A virus | NC_001489 | 7,478 | 0.38 | 18.7 | 24.0 | 25.5 | 19.9 | 28.0 |

| Kobuvirus | Aichi virus | NC_001918 | 8,251 | 0.59 | 23.2 | 23.3 | 31.8 | 23.8 | 35.1 |

| “Orthoturdivirus” (proposed) | “Turdivirus 1” | GU182406 | 8,019 | 0.58 | 22.1 | 20.7 | 32.1 | 22.7 | 36.8 |

| “Paraturdivirus” (proposed) | “Turdivirus 2” | GU182408 | 7,625 | 0.47 | 23.7 | 26.4 | 29.1 | 19.6 | 34.4 |

| Parechovirus | Human parechovirus | NC_001897 | 7,348 | 0.39 | 18.6 | 25.9 | 26.5 | 20.2 | 29.4 |

| Senecavirus | Seneca Valley virus | NC_011349 | 7,310 | 0.51 | 27.9 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 20.8 | 30.0 |

| Teschovirus | Porcine teschovirus 1 | NC_003985 | 7,117 | 0.45 | 25.2 | 24.7 | 31.3 | 24.8 | 34.9 |

| Tremovirus | Avian encephalomyelitis virus | NC_003990 | 7,055 | 0.45 | 19.6 | 25.7 | 28.8 | 25.1 | 29.8 |

| Sapelovirus | Simian sapelovirus (simian picornavirus 1) | NC_004451 | 8,126 | 0.40 | 45.3 | 45.8 | 58.6 | 45.6 | 64.6 |

| Porcine sapelovirus 1 | NC_003987 | 7,491 | 0.41 | 43.8 | 38.9 | 56.6 | 48.9 | 60.0 | |

| Avian sapelovirus | NC_006553 | 8,226 | 0.43 | 42.0 | 38.6 | 53.3 | 39.9 | 59.1 | |

| Unclassified | Pigeon picornavirus B | NC_015626 | 7,801 | 0.46 | 37.3 | 37.2 | 46.5 | 38.9 | 50.1 |

| Bat picornavirus group 1 | HQ595340 | 7,737 | 0.45 | 51.2 | 52.3 | 60.2 | 50.8 | 63.9 | |

| Bat picornavirus group 2 | HQ595342 | 7,677 | 0.43 | 51.0 | 51.4 | 61.1 | 51.9 | 64.8 | |

| Bat picornavirus group 3 | HQ595344 | 7,731 | 0.50 | 52.6 | 54.6 | 65.0 | 62.8 | 66.9 | |

| Feline picornavirus strain 356F | JN572117 | 7,415 | 0.50 | ||||||

P2 region excluding 2A.

P3 region excluding 3A.

Genome analyses.

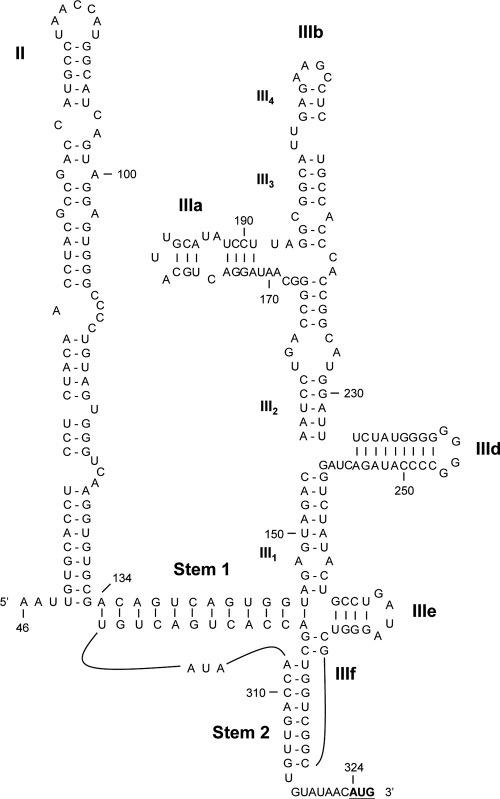

The 5′UTR of FePV possessed a similar IRES structure to that of type IV or hepacivirus/pestivirus (HP)-like internal ribosome entry site/segment (IRES) with stem-loop domains II to III (Fig. 4). This is similar to sapeloviruses and bat picornavirus groups 1 and 2 but different from the type I IRES observed in bat picornavirus group 3 (Table 2). The IRESs of picornaviruses are responsible for directing the initiation of translation in a cap-independent manner, which requires both canonical translation initiation and IRES trans-acting factors (50). The putative translation initiation site of FePV was contained by an optimal Kozak context (RNNAUGG), with in-frame AUG at position 324. The UANCCAU loop, found in domain II of the IRESs of hepatitis C virus (HCV), avian encephalomyelitis virus (AEV), classical swine fever virus (CSFV), and bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), was also present (23). Domain IIIa of FePV IRES contained a sequence of 18 nucleotides (GGACUGCAUUGCAUAUCC), identical to that found in porcine teschovirus 1 (23). In addition, the 5′UTR of FePV consisted of a stretch of 17 nucleotides (UACUGCCGAUAGGGUC), identical to that found in porcine sapelovirus (formerly porcine enterovirus A [PEVA]), which contained the most conserved domain IIIe and the four upstream nucleotides of type IV IRES (23). No obvious pyrimidine tract can be found near the translation initiation site.

Fig 4.

Predicted type IV IRES structures of FePV. Domain numbers and pseudoknot stem elements were labeled according to the labeling system of Hellen and de Breyne (23). The AUG start codon is shown in boldface type and underlined.

Table 2.

Comparison of genomic and protein features of FePV to those of different genera in the Picornaviridae family

| Region | Genomic or protein featurea | Genomic or protein feature in the following genus in the Picornaviridae familyb: |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphthovirus | Avihepatovirus | Cardiovirus | Enterovirus | Erbovirus | Hepatovirus | Kobuvirus | Parechovirus | Sapelovirus | Senecavirus | Teschovirus | Tremovirus | Proposed Orthoturdivirus (TV1) | Proposed Paraturdivirus (TV2 and TV3) | Unclassified (BatPV1 and BatPV2) | Unclassified (BatPV3) | Unclassified (feline picornavirus) | ||

| 5′UTR | Yn-Xm-AUG patternc | Y10X15 (FMDV-C) | Y7X65(DHV1) | Y9X18 (EMCV) | Y9X18 (PV) | Y12X15 (ERBV) | Y9X14 (HAV) | Y7X11 (AiV) | Y7X20 (HPeV2) | Y16-17 X17-18 (SpV1) | No (SVV-001) | Y7X13 (PTV1) | No (AEV) | Y9X19 | Y6X19-34 | No | Y8X19 | No |

| IRES (2, 13, 23) | Type II | Type IV | Type II | Type I | Type II | HAV-like | Type II or type IVg | Type II | Type IV | Type IV | Type IV | Type IV | Undefined | Undefined | Type IV | Type I | Type IV | |

| L | Proteased (17, 48) | Y† | N† | Y/N† | N† | Y† | N† | Y/N† | N† | Y/N† | Y/N† | Y/N† | N† | Y/N† | Y/N† | Y/N† | Y/N† | Y/N† |

| VP0 | Cleaved into VP4 and VP2 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Myristylation site GXXX[ST](7) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| VP1 | [PS]ALXAXETG motif | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | [AS]ALXAXETG |

| 2A | Function(s) (9, 26, 49, 61) | NPGP | NPGP, H-box/NC | NPGP | Chymotrypsin-like protease | NPGP | Unknowne | H-box/NC | H-box/NC in HPeV and LV; NPGP in LV | Chymotrypsin-like protease or unknowne | NPGP | NPGP | H-box/NC | H-box/NC | Unknowne | Chymotrypsin-like protease | Chymotrypsin-like protease | Chymotrypsin-like protease |

| 2C | NTPase motif GXXGXGKS (16) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Helicase DDLXQf (18) | Y§ | DDFGQ | Y§ | Y§ | Y§ | DD[LI]GQ | DD[LI]GQ | DD[LA]GQ | Y§ | Y§ | Y§ | Y§ | DDVGQ | Y§ | Y§ | DDVGQ | DDVGQ | |

| 3Cpro | Catalytic triad H-D/E-C (15) | H-D-C | H-D-C | H-D-C | H-E-C | H-D-C | H-D-C | H-E-C | H-D-C | H-E-C | H-D-C | H-D-C | H-D-C | H-E-C | H-E-C | H-E-C | H-E-C | H-D-C |

| RNA-binding domain motif KFRDI (22) | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | NFRDI | KYRDI | K[FY]RDI | |

| GXCG or GXH motif (15) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | AMH | Y | A[MI]H | |

| 3Dpol | KDE[LI]R motif (29) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| GG[LMN]PSG motif (29) | Y | GGMCSG | Y | Y | GALPSG | GSMPSG | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | GSMPSG | Y | GGMPS[GR] | Y | Y | Y | |

| YGDD motif (29) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| FLKR motif (29) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

The genomic or protein features shown include conserved motifs, features, and functions. References are shown in parentheses.

For some genomic or protein features, the sequences or type are shown. The presence or absence of other features is shown as follows: Y, present; N, absent. Virus abbreviations are as definted in the text or the legend to Fig. 1. PV, poliovirus.

The Yn-Xm-AUG pattern is shown as follows. The number of Y nucleotides and the number of X nucleotides follow the nucleotide letter. For SpV1 in the Sapelovirus genus, there are 16 or 17 Y nucleotides and 17 or 18 X nucleotides. For the proposed Paraturdivirus (TV2 and TV3), there are 6 Y nucleotides and 19 to 34 X nucleotides.

Symbols for protease: Y†, presence of L, and L is protease; Y/N†, presence of L, but L is not protease; N†, absence of L.

2A of HAV, DPV, TV2, and TV3 do not contain the characteristic catalytic amino acid residues with chymotrypsin-like proteolytic activity, the NPGP motif or the H-box/NC motif.

For helicase DDLXQ, Y§ indicates that motif DDLXQ is present. If the motif is different, it is shown.

Porcine kobuvirus SUN-1-HUN was predicted to have type IV IRES.

The L protein of FePV exhibited very low (≤23.6%) amino acid identities to those of known picornaviruses and was the shortest L protein (50 aa) among those of known picornaviruses (range, 50 to 451 aa), compared to another short L protein of 55 aa in bat picornavirus group 3. This L protein shared 74% to 98% amino acid identities among the five FePV strains. It does not possess the characteristic amino acid residues important for proteolytic activity. The catalytic dyad, Cys and His, conserved in papain-like thiol protease, has been found in the L proteins of aphthoviruses and erboviruses (19, 25). Although the L protein of FePV possessed Cys and His residues, we cannot conclude that it possesses proteolytic ability because of poor sequence alignment. The L protein of FePV also did not possess the GXCG motif, suggesting that it probably does not have chymotrypsin-like protease activity (54). Moreover, it did not contain the putative zinc finger motifs found in cardioviruses such as Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) and encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), which were important in the regulation of viral genome translation (5, 12). The function of the L protein of FePV remains to be determined.

The P1 (capsid-coding) regions in the genomes of FePV contain the capsid genes VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1. FePV possessed Thr or Val at the C termini of L and VP1, at the L/VP4 and VP1/2A cleavage junctions, respectively, distinct from those observed in sapeloviruses and bat picornaviruses, although Thr was also observed at the VP1/2A junction in sapeloviruses (Fig. 2). The VP0 protein of FePV is probably cleaved into VP4 and VP2 based on sequence alignment (Fig. 2). The VP1 protein of FePV possessed the [PS]ALXAXETG motif although the first amino acid was substituted by alanine in two strains, 127F and 661F (Table 2).

The P2 regions in the genomes of FePV carry the genes that encode nonstructural proteins 2A, 2B, and 2C. The 2A protein of picornaviruses is also a highly variable region (9 to 305 aa). The 2A protein of FePV (200 amino acids in length) exhibited very low (≤29%) amino acid identities to those of other picornaviruses. This 2A protein shared 84% to 99.5% amino acid identities among the five FePV strains. The 2A protein of FePV possessed the characteristic chymotrypsin-like structures with cysteine-reactive catalytic sites (Table 2). A putative catalytic triad of His-Asp-Cys found in 2A proteinases of enteroviruses and rhinoviruses, was also identified (26, 49). The conserved GXCG motif in chymotrypsin-like protease, present in the 2A proteins of simian and porcine sapeloviruses, but not avian sapelovirus (26, 33, 55), was also identified in the 2A protein of FePV as GSCG. However, the Asn-Pro-Gly-Pro (NPGP) motif found in 2A and 2B of aphthovirus and cardiovirus, required for cotranslational cleavage (49), was absent in FePV. The conserved H-box/NC motif involved in cell proliferation control was also absent (26, 55, 60). Similar to other picornaviruses, 2C of FePV possessed the GXXGXGKS motif for NTP binding (16). Similar to turdivirus 1 and bat picornavirus group 3, the Leu of the DDLXQ motif, important for putative helicase activity, was replaced by Val (18). This is similar to some picornaviruses in which Leu can be replaced by another nonpolar amino acid (8, 41, 47, 55, 62).

The P3 regions in the genomes of the FePV strains carry the genes that encode 3A, 3B (VPg, small genome-linked protein), 3Cpro (protease), and 3Dpol (RN-dependent RNA polymerase). FePV possessed Glu at the C terminus of 3C at the 3C/3D cleavage junction, distinct from the Gln observed in sapeloviruses and bat picornaviruses (Fig. 2). Unlike the 3Cpro of sapelovirus and the closely related bat picornaviruses, which contained the catalytic triad H-E-C, the 3Cpro of FePV contained H-D-C (Table 2) (1). It also contained the conserved GXCG motif which forms part of the active site of the protease, and the conserved RNA-binding motif, K[FY]RDI (15, 22). As in bat picornavirus groups 1 and 2, the Gly in the conserved GXH motif of 3Cpro in FePV was replaced by Ala. The 3Dpol of FePV contained the conserved KDE[LI]R, GG[LMN]PSG, YGDD, and FLKR motifs (29).

Using the five FePV genome sequences for analysis, the Ka/Ks ratios for the various coding regions were calculated (Table 3). The highest Ka/Ks ratio was observed at the L protein, although all Ka/Ks ratios were generally low, suggesting that the FePV genome was under purifying selection.

Table 3.

Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates of each coding region among the genomes of the five FePV strainsa

| Putative protein | No. of amino acids | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | 50 | 0.099 | 0.520 | 0.190 |

| VP4 | 64 | 0.041 | 0.988 | 0.042 |

| VP2 | 240 | 0.029 | 1.221 | 0.024 |

| VP3 | 226 | 0.027 | 1.141 | 0.024 |

| VP1 | 305 | 0.051 | 1.250 | 0.041 |

| 2A | 200 | 0.061 | 1.087 | 0.056 |

| 2B | 103 | 0.035 | 1.047 | 0.033 |

| 2C | 336 | 0.018 | 1.044 | 0.017 |

| 3A | 147 | 0.053 | 0.998 | 0.053 |

| 3B | 23 | 0.011 | 0.649 | 0.017 |

| 3C | 182 | 0.023 | 1.048 | 0.022 |

| 3D | 461 | 0.027 | 0.903 | 0.030 |

Ka is the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site, and Ks is the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site.

Seroprevalence of FePV in stray cats.

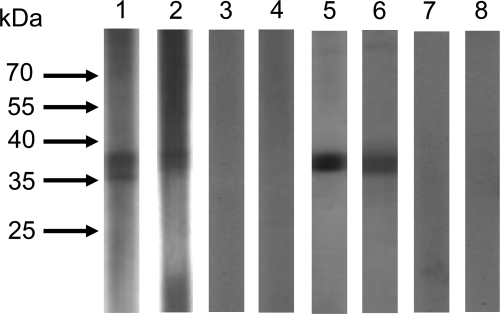

To determine the seroprevalence of FePV in stray cats, Western blot analysis using the recombinant FePV VP1 polypeptide was performed. For IgG detection, prominent immunoreactive protein bands of about 36 kDa were observed in 78 (33.6%) of the tested plasma samples from 232 cats, including the 14 cats with FePV detected in fecal samples, in the recombinant FePV VP1 protein-based Western blot assay (Fig. 5). Positive IgG was detected in 3 (21.4%) of 14 plasma samples from cats positive for FePV in their fecal samples and 75 (34.4%) of 218 plasma samples from cats negative for FePV in their fecal samples. In addition, 28 available plasma samples from the 14 cats positive and 14 cats negative for FePV in fecal samples were subjected to IgM detection, among which 3 (10.7%) tested positive for IgM (Fig. 5). Positive IgM was detected in 3 (21.4%) of 14 plasma samples from cats positive for FePV in their fecal samples but none (0%) of 14 plasma samples from cats negative for FePV in their fecal samples. Among the plasma samples tested from the 14 cats positive for FePV in their fecal samples, two were positive for both IgM and IgG, one was positive for IgM only. and one was positive for IgG only.

Fig 5.

Western blot analysis against purified His6-tagged recombinant VP1 polypeptide of FePV using plasma samples from stray cats. Prominent immunoreactive protein bands with the expected size of around 36 kDa of the recombinant FePV VP1 polypeptide were detected with plasma samples from stray cats for both IgM (lanes 1 and 2, positive; lanes 3 and 4, negative) and IgG (lanes 5 and 6, positive; lanes 7 and 8, negative).

Viral culture.

No cytopathic effect was observed in any of the cell lines inoculated with the samples that were positive for FePV by RT-PCR. RT-PCR using the culture supernatants and cell lysates for monitoring the presence of viral replication also showed negative results.

DISCUSSION

We report the discovery of a novel feline picornavirus (FePV) from stray cats in Hong Kong, which represents the first documentation of a picornavirus in the domestic cat (Felis catus). In this study, FePV was detected in the fecal samples from 14 (2.1%) of 662 stray cats and in two urine samples. Analysis of the complete genomes of five FePV strains showed that they formed a distinct group among known picornaviruses in all three phylogenetic trees constructed using the P1, P2 (excluding 2A), and P3 (excluding 3A) regions with a very high bootstrap value of 100 (Fig. 3). The presence of closely related strains of FePV under purifying selection in a significant proportion of these stray cats suggested that these animals are likely the natural reservoir of this novel picornavirus. Western blot analysis revealed a high seroprevalence of 33.6% among the animals tested for IgG against recombinant FePV VP1 polypeptide, suggesting that infection by FePV is common in the cat population studied. The detection of IgM in the plasma samples from three cats positive for FePV in fecal samples, but not from cats negative for FePV, also supports recent infection by FePV in these animals. Since only stray cats were included in the present study, further studies are important to understand the prevalence and epidemiology of FePV in cats living in domestic environments and in other countries.

In addition to its distinct phylogenetic position, FePV also exhibits genome and protein features different from those of known members of the family Picornaviridae. Analysis of the FePV genome showed that this virus is more closely related to the bat picornaviruses than to members of the known genus Sapelovirus. The P1, P2 (excluding 2A), and P3 (excluding 3A) of FePV possessed 42.0% to 45.3%, 38.6% to 45.8%, and 53.3% to 58.6% amino acid identities to the corresponding regions in sapeloviruses, respectively, whereas they possessed 51.0% to 52.6%, 51.4% to 54.6%, and 60.2% to 65.0% amino acid identities to the corresponding regions in bat picornaviruses, respectively (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis also showed that FePV always formed a distinct cluster with the bat picornaviruses separate from the sapeloviruses (Fig. 2). In contrast to sapelovirus genomes with a G+C content of 40 to 43%, FePV possessed a higher G+C content of 50 to 51%. In fact, analysis of both the G+C content and amino acid sequences of the P1, P2 (excluding 2A), and P3 (excluding 3A) regions showed that FePV is most closely related to the recently described bat picornavirus group 3, which itself may belong to a distinct genus in the Picornaviridae, than to members of the genus Sapelovirus (Table 1) (35). However, FePV possessed a type IV IRES, as opposed to a type I IRES observed for bat picornavirus group 3. FePV also possessed other features different from those of sapeloviruses and bat picornaviruses, including distinct cleavage sites at the 3C/3D junction and a catalytic triad of H-D-C in 3Cpro. Moreover, the L and 2A proteins of FePV exhibited very low similarity (≤23.6% and ≤29% amino acid identities, respectively) to those of other known picornaviruses. On the basis of these results, we believe that FePV may be more appropriately classified under a new genus separate from Sapelovirus, although it remains to be determined if it should belong to the same genus together with the bat picornaviruses (32, 45, 54).

The existence of apparently one picornavirus species in the cats studied suggests a high degree of species specificity in FePV. In the present study, the five strains of FePV exhibited high sequence similarities and similar genome organizations, suggesting a single species of FePV. Nevertheless, two potential genotypes of FePV were identified. Upon phylogenetic analysis of VP1 nucleotide sequences, two distinct clusters of sequences were found, with very high bootstrap support of 1,000 among strains within each cluster (Fig. 3). Therefore, these two clusters likely represent two different genotypes, genotypes A and B, of FePV, which differed from each other by 24.3 to 25.3% in their VP1 gene sequences. Such genetic difference is comparable to that between the three genotypes of enterovirus 71, with nucleotide sequence variation of 16.5 to 19.7% based on VP1 gene analysis (4). The observed species specificity of FePV is in contrast to the ability of bat picornavirus groups 1 to 3 to infect bats of different genera or species, which may be explained by the large species diversity of bats, their ability to fly, and tendency to roost (35). Although we found no evidence for recombination in the present FePV strains (data not shown), other viruses from cats, such as feline coronaviruses and felis domesticus papillomavirus, have been shown to be closely related to or to recombine with their counterparts in dogs, suggesting that these feline viruses may have the potential to cross the species barrier in animals in similar living habitats (24, 52). As picornaviruses are also known for their potential for recombination (3, 63) and given the close association of the domestic cat with humans, it would be important to monitor the genetic evolution of FePV and to study their potential for interspecies transmission.

The pathogenicity of FePV in cats remains to be determined. Picornaviruses closely related to FePV, such as members of the genus Sapelovirus, are not very pathogenic to their hosts. First isolated from the intestines of ducks with signs of hepatitis, duck sapelovirus was found to inhibit the growth of day-old ducklings but did not cause mortality (54). Porcine sapelovirus generally causes asymptomatic enteric infections of swine, while little is known regarding the pathogenicity of simian sapelovirus (28, 32). The recently described bat picornavirus groups 1, 2, and 3 were detected in the fecal samples from apparently healthy bats (35). In this study, all 14 cats with positive results for FePV in their fecal samples were apparently healthy. Interestingly, the virus was also detected in the urine samples from two cats, which is in line with the shedding of human enteroviruses in urine (21) and suggests a possible wide tissue tropism. Further studies are required to determine whether the present novel picornavirus cause any disease in the domestic cat.

Having been associated with humans for at least 9,500 years, domestic cats usually pose little physical danger to humans. However, as a result of cat bites or via other modes of transmission, cats can affect human health with infections caused by a range of pathogens, including bacteria (e.g., cat scratch disease), parasites (e.g., toxoplasmosis), and more rarely viruses (e.g., rabies). Apart from the present novel picornavirus, viruses of at least 14 families, including Adenoviridae, Astroviridae, Bornaviridae, Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae, Flaviviridae, Herpesviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Papillomaviridae, Parvoviridae, Poxviridae, Reoviridae, Retroviridae, and Rhabdoviridae, have been found to infect cats. Domestic cats have also been shown to be susceptible to infection by SARS coronavirus and highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses H5N1 and H7N7, suggesting that these animals can be susceptible to viruses that can cause serious infections in humans and other animals (42, 43, 56). As cats live closely with humans, continuous surveillance of viruses in these animals is important to understand their potential for emergence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alan Chi-Kong Wong, Siu-Fai Leung, Thomas Hon-Chung Sit, and Howard Kai-Hay Wong (HKSAR Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Conservation [AFCD]) for facilitation and support and veterinary officers of the AFCD Animal Management Centres for assistance and collection of samples. We are grateful to the generous support of Carol Yu, Richard Yu, Hui Hoy, and Hui Ming in the genomic sequencing platform.

This work was partly supported by the Research Grant Council grant (HKU 783611 M) from the University Grant Council; Committee for Research and Conference Grant, Strategic Research Theme Fund, and University Development Fund, The University of Hong Kong; the HKSAR Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Diseases of the Health, Welfare and Food Bureau; the Providence Foundation Limited in memory of the late Lui Hac Minh; and Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Disease for the HKSAR Department of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 October 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Bazan JF, Fletterick RJ. 1988. Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:7872–7876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belsham GJ. 2009. Divergent picornavirus IRES elements. Virus Res. 139:183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benschop KS, et al. 2010. Comprehensive full-length sequence analyses of human parechoviruses: diversity and recombination. J. Gen. Virol. 91:145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown BA, Oberste MS, Alexander JP, Jr, Kennett ML, Pallansch MA. 1999. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of enterovirus 71 strains isolated from 1970 to 1998. J. Virol. 73:9969–9975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen HH, Kong WP, Roos RP. 1995. The leader peptide of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus is a zinc-binding protein. J. Virol. 69:8076–8078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chiu CY, et al. 2008. Identification of cardioviruses related to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus in human infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14124–14129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chow M, et al. 1987. Myristylation of picornavirus capsid protein VP4 and its structural significance. Nature 327:482–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen JI, Ticehurst JR, Purcell RH, Buckler-White A, Baroudy BM. 1987. Complete nucleotide sequence of wild-type hepatitis A virus: comparison with different strains of hepatitis A virus and other picornaviruses. J. Virol. 61:50–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doherty M, Todd D, McFerran N, Hoey EM. 1999. Sequence analysis of a porcine enterovirus serotype 1 isolate: relationships with other picornaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1929–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drexler JF, et al. 2010. Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J. Virol. 84:11336–11349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drexler JF, et al. 2008. Circulation of 3 lineages of a novel Saffold cardiovirus in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1398–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dvorak CM, et al. 2001. Leader protein of encephalomyocarditis virus binds zinc, is phosphorylated during viral infection, and affects the efficiency of genome translation. Virology 290:261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fernandez-Miragall O, Lopez de Quinto S, Martinez-Salas E. 2009. Relevance of RNA structure for the activity of picornavirus IRES elements. Virus Res. 139:172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Francis MJ, et al. 1987. A synthetic peptide which elicits neutralizing antibody against human rhinovirus type 2. J. Gen. Virol. 68:2687–2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gorbalenya AE, Donchenko AP, Blinov VM, Koonin EV. 1989. Cysteine proteases of positive strand RNA viruses and chymotrypsin-like serine proteases. A distinct protein superfamily with a common structural fold. FEBS Lett. 243:103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV, Donchenko AP, Blinov VM. 1989. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:4713–4730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV, Lai MM. 1991. Putative papain-related thiol proteases of positive-strand RNA viruses. Identification of rubi- and aphthovirus proteases and delineation of a novel conserved domain associated with proteases of rubi-, alpha- and coronaviruses. FEBS Lett. 288:201–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV, Wolf YI. 1990. A new superfamily of putative NTP-binding domains encoded by genomes of small DNA and RNA viruses. FEBS Lett. 262:145–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gradi A, et al. 2004. Cleavage of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GII within foot-and-mouth disease virus-infected cells: identification of the L-protease cleavage site in vitro. J. Virol. 78:3271–3278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 5:696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Halonen P, et al. 1995. Detection of enteroviruses and rhinoviruses in clinical specimens by PCR and liquid-phase hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:648–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hammerle T, Molla A, Wimmer E. 1992. Mutational analysis of the proposed FG loop of poliovirus proteinase 3C identifies amino acids that are necessary for 3CD cleavage and might be determinants of a function distinct from proteolytic activity. J. Virol. 66:6028–6034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hellen CU, de Breyne S. 2007. A distinct group of hepacivirus/pestivirus-like internal ribosomal entry sites in members of diverse picornavirus genera: evidence for modular exchange of functional noncoding RNA elements by recombination. J. Virol. 81:5850–5863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herrewegh AA, Smeenk I, Horzinek MC, Rottier PJ, de Groot RJ. 1998. Feline coronavirus type II strains 79-1683 and 79-1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. J. Virol. 72:4508–4514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hinton TM, Ross-Smith N, Warner S, Belsham GJ, Crabb BS. 2002. Conservation of L and 3C proteinase activities across distantly related aphthoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 83:3111–3121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hughes PJ, Stanway G. 2000. The 2A proteins of three diverse picornaviruses are related to each other and to the H-rev107 family of proteins involved in the control of cell proliferation. J. Gen. Virol. 81:201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones MS, Lukashov VV, Ganac RD, Schnurr DP. 2007. Discovery of a novel human picornavirus in a stool sample from a pediatric patient presenting with fever of unknown origin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2144–2150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kalter SS. 1982. Enteric viruses of nonhuman primates. Vet. Pathol. 19:33–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamer G, Argos P. 1984. Primary structural comparison of RNA-dependent polymerases from plant, animal and bacterial viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:7269–7282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapoor A, et al. 2008. A highly divergent picornavirus in a marine mammal. J. Virol. 82:311–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kapoor A, et al. 2008. A highly prevalent and genetically diversified Picornaviridae genus in South Asian children. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:20482–20487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krumbholz A, et al. 2002. Sequencing of porcine enterovirus groups II and III reveals unique features of both virus groups. J. Virol. 76:5813–5821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamphear BJ, et al. 1993. Mapping the cleavage site in protein synthesis initiation factor eIF-4 gamma of the 2A proteases from human coxsackievirus and rhinovirus. J. Biol. Chem. 268:19200–19203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lau SKP, et al. 2008. Identification of novel porcine and bovine parvoviruses closely related to human parvovirus 4. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1840–1848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lau SKP, et al. 2011. Complete genome analysis of three novel picornaviruses from diverse bat species. J. Virol. 85:8819–8828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lau SKP, et al. 2010. Coexistence of different genotypes in the same bat and serological characterization of Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9 belonging to a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup. J. Virol. 84:11385–11394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37. Lau SKP, et al. 2009. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human rhinovirus C in children and adults in Hong Kong reveals a possible distinct human rhinovirus C subgroup. J. Infect. Dis. 200:1096–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lau SKP, et al. 2007. Clinical features and complete genome characterization of a distinct human rhinovirus (HRV) genetic cluster, probably representing a previously undetected HRV species, HRV-C, associated with acute respiratory illness in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3655–3664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lau SKP, et al. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:14040–14045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li L, et al. 2009. A novel picornavirus associated with gastroenteritis. J. Virol. 83:12002–12006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindberg AM, Johansson S. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of Ljungan virus and A-2 plaque virus, new members of the Picornaviridae. Virus Res. 85:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marschall J, Hartmann K. 2008. Avian influenza A H5N1 infections in cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 10:359–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martina BE, et al. 2003. Virology: SARS virus infection of cats and ferrets. Nature 425:915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McErlean P, et al. 2008. Distinguishing molecular features and clinical characteristics of a putative new rhinovirus species, human rhinovirus C (HRV C). PLoS One 3:e1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oberste MS, Maher K, Pallansch MA. 2003. Genomic evidence that simian virus 2 and six other simian picornaviruses represent a new genus in Picornaviridae. Virology 314:283–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Racaniello VR. 2007. Picornaviridae: the viruses, their replication,p 795–829 In Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed Lippincott-Raven, Pennsylvania, PA [Google Scholar]

- 47. Racaniello VR, Baltimore D. 1981. Molecular cloning of poliovirus cDNA and determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of the viral genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:4887–4891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roberts PJ, Belsham GJ. 1995. Identification of critical amino acids within the foot-and-mouth disease virus leader protein, a cysteine protease. Virology 213:140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ryan MD, Flint M. 1997. Virus-encoded proteinases of the picornavirus super-group. J. Gen. Virol. 78:699–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shih S-R, Stollar V, Li M-L. 2011. Host factors in enterovirus 71 replication. J. Virol. 85:9658–9666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Terai M, Burk RD. 2002. Felis domesticus papillomavirus, isolated from a skin lesion, is related to canine oral papillomavirus and contains a 1.3 kb non-coding region between the E2 and L2 open reading frames. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2303–2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tracy S, Chapman NM, Drescher KM, Kono K, Tapprich W. 2006. Evolution of virulence in picornaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 299:193–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tseng CH, Tsai HJ. 2007. Sequence analysis of a duck picornavirus isolate indicates that it together with porcine enterovirus type 8 and simian picornavirus type 2 should be assigned to a new picornavirus genus. Virus Res. 129:104–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tseng CH, Knowles NJ, Tsai HJ. 2007. Molecular analysis of duck hepatitis virus type 1 indicates that it should be assigned to a new genus. Virus Res. 123:190–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Riel D, Rimmelzwaan GF, van Amerongen G, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T. 2010. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H7N7 isolated from a fatal human case causes respiratory disease in cats but does not spread systemically. Am. J. Pathol. 177:2185–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Woo PCY, et al. 2007. Comparative analysis of 12 genomes of three novel group 2c and group 2d coronaviruses reveals unique group and subgroup features. J. Virol. 81:1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Woo PCY, et al. 2009. Comparative analysis of complete genome sequences of three avian coronaviruses reveals a novel group 3c coronavirus. J. Virol. 83:908–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Woo PCY, et al. 2006. Molecular diversity of coronaviruses in bats. Virology 351:180–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Woo PCY, et al. 2010. Comparative analysis of six genome sequences of three novel picornaviruses, turdiviruses 1, 2 and 3, in dead wild birds, and proposal of two novel genera, Orthoturdivirus and Paraturdivirus, in the family Picornaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 91:2433–2448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wutz G, et al. 1996. Equine rhinovirus serotypes 1 and 2: relationship to each other and to aphthoviruses and cardioviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 77:1719–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yamashita T, et al. 1998. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of Aichi virus, a distinct member of the Picornaviridae associated with acute gastroenteritis in humans. J. Virol. 72:8408–8412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yip CCY, et al. 2010. Emergence of enterovirus 71 “double-recombinant” strains belonging to a novel genotype D originating from southern China: first evidence for combination of intratypic and intertypic recombination events in EV71. Arch. Virol. 155:1413–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zuker M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]