Abstract

Pulmonary delivery of an influenza Iscomatrix adjuvant vaccine induces a strong systemic and mucosal antibody response. Since an influenza vaccine needs to induce immunological memory that lasts at least 1 year for utility in humans, we examined the longevity of the immune response induced by such a pulmonary vaccination, with and without antigen challenge. Sheep were vaccinated in the deep lung with an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine, and serum and lung antibody levels were quantified for up to 1 year. The immune memory response to these vaccinations was determined following antigen challenge via lung delivery of influenza antigen at 6 months and 1 year postvaccination. Pulmonary vaccination of sheep with the influenza Iscomatrix vaccine induced antigen-specific antibodies in both sera and lungs that were detectable until 6 months postimmunization. Importantly, a memory recall response following antigenic challenge was detected at 12 months post-lung vaccination, including the induction of functional antibodies with hemagglutination inhibition activity. Pulmonary delivery of an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine induces a long-lived influenza virus-specific antibody and memory response of suitable length for annual vaccination against influenza.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza remains one of the biggest global health issues, due to its potential for rapid spread and high morbidity and mortality rates. Vaccination inducing long-term immunity is still regarded as the best means of protection against influenza. However, the available annual influenza vaccines are unable to induce responses of this kind in the pediatric and elderly populations, leaving many individuals in these age groups susceptible to influenza virus-induced disease (11). Currently available influenza vaccines are typically given as intramuscular injections containing 15 μg (each) of the 3 most prevalent circulating strains of the virus. These are given on an annual basis in order to ensure the presence of a protective level of influenza virus-specific antibody for the duration of the peak influenza season, which is generally 3 to 6 months. In seasons where there is a delay between vaccination and the peak in circulating virus, a sufficiently strong immunological memory/recall response is required to provide protection for at least a year after vaccination.

Injected vaccines can induce strong systemic immune responses but are not very efficient at inducing immune responses at mucosal sites, the primary route by which influenza virus infects its host. Mucosal delivery has considerable potential for improving the effectiveness of vaccination against mucosal pathogens, by increasing immunity at the sites of infection. A number of studies have been carried out to investigate the potential of utilizing the lungs for the induction of protective immune responses, with encouraging results (9, 10, 13).

Recently, we demonstrated the capacity of pulmonary delivery of an influenza Iscomatrix adjuvant vaccine to induce strong systemic and mucosal immune responses (15). Iscomatrix adjuvant typically consists of 40-nm cage-like structures comprising a purified fraction of quillaia saponin, cholesterol, and phospholipid and has previously been shown to induce strong influenza virus-specific systemic but not mucosal immune responses to influenza virus and other codelivered antigens following systemic delivery (8). Our results showed that pulmonary delivery of an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine into sheep induced a potent mixed systemic and mucosal immune response, even with a significant reduction in antigen dose (375 times less), compared to subcutaneous injection with a current vaccine equivalent (15). Moreover, this response was dependent on both the presence of Iscomatrix adjuvant in the formulation and delivery to the deep lung (15). We were further able to demonstrate similar effects when recombinant antigens from other pathogens (cytomegalovirus and Helicobacter pylori) were combined with Iscomatrix adjuvant and delivered via the pulmonary route (14). Taken together, these findings support the utility of pulmonary Iscomatrix vaccines for the induction of strong systemic and mucosal immune responses.

An essential requirement of any vaccine is the induction of long-term protective immunity. Since our previous studies followed immunity for only up to a month following pulmonary vaccination, information regarding the longevity of the induced immune response was lacking. We therefore explored the ability of pulmonary vaccination to induce long-term immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Female Merino ewes were housed in paddocks at the CSL Rosehill Farm, Woodend, Victoria, Australia. Sheep were fed lucerne chaff mixed with commercial pellets and allowed access to water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the CSL Limited Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Pulmonary vaccinations.

The influenza virus antigen was sucrose gradient-purified A/Solomon Islands/03/2006 H1N1 virus which had been inactivated and detergent disrupted. Antigen concentration was based on hemagglutinin content and determined by single radial immunodiffusion assay. Good manufacturing practice (GMP)-grade Iscomatrix adjuvant was prepared by CSL Limited as previously described (5).

For immunizations, sheep were carefully restrained in a harness, and a bronchoscope (Pentax 16FG) lubricated with a lidocaine gel was inserted via the nostril to the lower caudal lobe of the lung. Vaccines were infused in a total volume of 5 ml, followed by 10 ml of air to ensure complete delivery. Sheep received three immunizations, each separated by 3 weeks.

For analyses of induced immunity, serum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected. Blood (10 ml) was collected from the jugular vein by using an 18G needle with a syringe and then was left to coagulate for collection of serum. For collection of BAL fluid, 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was delivered into the caudal lobe of the lung via a bronchoscope and then immediately withdrawn. Samples were stored at −20°C until analyzed.

Evaluation of antibody responses by ELISA.

Antigen-specific antibodies in BAL fluid and serum samples were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously (15). Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp flat-bottom plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight with 50 μl of 10-μg/ml antigen in carbonate buffer, pH 9.6. Plates were then blocked with 1% sodium casein before adding 100 μl of 1-in-5 serial dilutions of serum samples in duplicate. Binding of antigen-specific antibodies was detected using rabbit anti-sheep IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) or anti-bovine/ovine IgA (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) followed by rabbit anti-mouse–horseradish peroxidase (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Color was developed by addition of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) and stopped by addition of 2 M H2SO4, the optical density at 450 nm was determined on a Bio-Tek ELx800 plate reader, and endpoint titers were calculated.

Evaluation of HAI activity.

The hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay determines the titer of functional antibodies by measuring the inhibition of red blood cell agglutination by influenza virus. Serum and BAL fluid samples were tested for HAI activity against egg-grown A/Solomon Island/03/2006 virus (H1N1) by using turkey red blood cells according to the method of Kendal et al. (7). The HAI titer was determined as the dilution of sample that inhibited influenza virus agglutination of red blood cells.

Statistical analyses.

For all statistical analyses, data were log transformed and compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's post hoc analysis, using SPSS software, version 19.0.

RESULTS

Longevity of antibody response in sheep vaccinated by the pulmonary route.

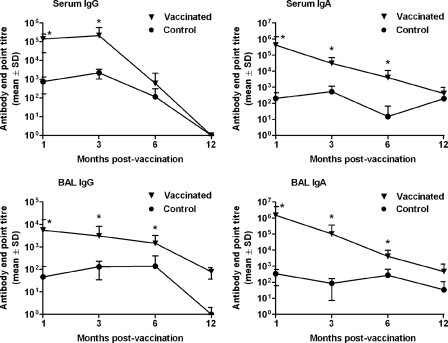

To examine the longevity of the immune response induced by pulmonary vaccination, sheep (n = 12) were vaccinated in the deep lung three times (21 days apart) with an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine comprising 15 μg influenza virus antigen and 75 Isco units of Iscomatrix adjuvant (an Isco unit relates to the amount of Iscoprep saponin, the immunomodulatory component, in the Iscomatrix adjuvant). Unvaccinated negative controls (n = 12) were given PBS alone. Influenza virus-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in prechallenge serum and BAL fluid samples collected at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postimmunization were quantified by ELISA (Fig. 1). Pulmonary vaccination induced significant systemic and mucosal antibody responses that were detectable for at least 6 months, with elevated anti-influenza virus IgG and IgA levels in the serum and BAL fluid compared to those for unvaccinated controls (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Longevity of mucosal and systemic antibody responses induced by pulmonary vaccination. Sheep received three vaccinations of 15 μg of influenza antigen and 75 Isco units of Iscomatrix adjuvant, delivered into the deep lung. Negative-control unvaccinated sheep (n = 12) received PBS alone. Serum and lung washings, collected 1 (n = 12), 3 (n = 12), 6 (n = 12), and 12 (n = 6) months after the third vaccination, were analyzed for the presence of anti-influenza virus IgG and IgA antibodies by ELISA. Immunization via the pulmonary route induced a significant antibody response for up to 6 months postvaccination compared with that of unvaccinated controls (*, P < 0.035; ANOVA).

Longevity of the memory response to antigenic challenge induced by pulmonary vaccination.

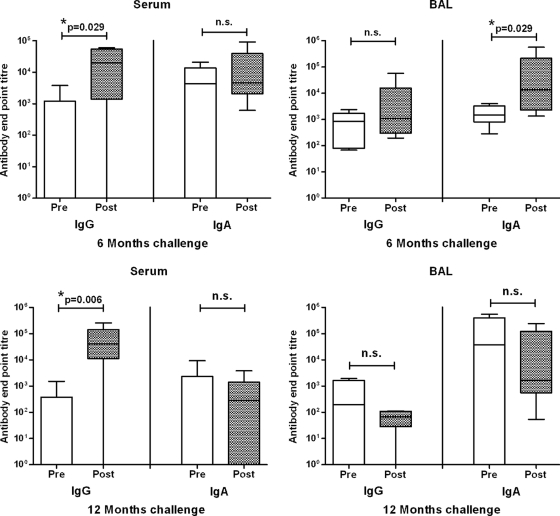

An important feature of a vaccine is its ability to induce a long-term memory response to antigenic challenge. Therefore, 1 week after collecting the 6-month (prechallenge) samples, half of animals in the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups (n = 6) received an antigenic challenge of 1 μg of influenza virus antigen (without adjuvant), delivered into the lung via a bronchoscope. Another week later, postchallenge serum and BAL fluid samples were collected from these animals. Antigenic challenge in the lung induced a significant increase in influenza virus-specific IgG in the serum and IgA in the BAL fluid of vaccinated animals (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Pulmonary vaccination induces a long-term immune memory response to antigen challenge. Sheep received three vaccinations of 15 μg of influenza antigen and 75 Isco units of Iscomatrix adjuvant, delivered into the deep lung (n = 12). Negative-control unvaccinated sheep (n = 12) received PBS alone. At 6 and 12 months postvaccination, six sheep from each group were challenged in the lung with influenza virus antigen. Serum and BAL fluid were collected 1 week prior to and 1 week after antigen challenge, and anti-influenza virus antibody levels were determined by ELISA. At both 6 and 12 months post-pulmonary vaccination, antigen challenge induced a strong antibody memory response, as indicated by significantly elevated anti-influenza virus antibody levels (*, P < 0.001; ANOVA). Box plots present interquartile ranges (boxed regions) and 10th and 90th percentile values (error bars). n.s., not significantly different (P > 0.05; ANOVA). Antigen challenge induced no increase in titers in samples from unvaccinated controls (not shown).

Twelve months after the last vaccination, the remaining unchallenged sheep (n = 6 per group) were similarly challenged in the lung with influenza virus antigen. Since challenge with 1 μg of influenza virus antigen had not induced a detectable IgG memory response in BAL fluid at 6 months postvaccination, the antigen challenge dose was increased to 15 μg. While at 12 months postvaccination only low anti-influenza virus antibody levels were present in the serum or BAL fluid of sheep vaccinated in the lung before antigen challenge, 1 week following antigen exposure the vaccinated sheep responded with highly significant increases (up to 3 to 4 log) in the serum anti-influenza virus IgG antibody response, although no increase in BAL fluid antibodies was observed (Fig. 2).

Longevity of functional antibodies induced by pulmonary vaccination.

Serum HAI titers are an accepted correlate of protective immunity against influenza virus infection. Therefore, to examine whether pulmonary vaccination induced an antibody response with long-term functional activity, the HAI titers of serum and BAL fluid samples collected before and after antigen challenge were determined.

In sheep that received 3 pulmonary vaccinations of the influenza Iscomatrix vaccine, low HAI antibody responses were detected in the 6- and 12-month prechallenge serum and BAL fluid samples (Table 1). However, a functional memory response was demonstrated at both 6 and 12 months postvaccination, with a significant increase in serum HAI titer following antigen challenge (Table 1). While BAL fluid samples from vaccinated and challenged sheep had higher levels than those of unvaccinated controls at 12 months postvaccination, the difference did not reach significance.

Table 1.

Pulmonary vaccination induces a long-lasting functional antibody memory response

| Time postvaccinationa | HAI titer (geometric mean ± SD)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated animals |

Vaccinated animals |

|||

| Serum | BAL fluidc | Serum | BAL fluid | |

| 6 months prechallenge | 0 ± 0 | 16 ± 5 | 13 ± 5* | 25 ± 13 |

| 6 months postchallenge | 0 ± 0 | 16 ± 5 | 32 ± 13*# | 22 ± 15 |

| 12 months prechallenge | 0 ± 0 | 23 ± 20 | <10 | 16 ± 23 |

| 12 months postchallenge | 0 ± 0 | 36 ± 94 | 70 ± 4,568*# | 49 ± 100 |

Sheep received three vaccinations of 15 μg of influenza virus and 75 Isco units Iscomatrix adjuvant, delivered into the deep lung (n = 12). Negative-control sheep (n = 12) were left unvaccinated. At 6 months postvaccination, half of each group (n = 6) was challenged in the lung with 1 μg influenza virus antigen. At 12 months postvaccination, the remaining sheep from each group were challenged in the lung with 15 μg influenza virus antigen.

Serum and BAL fluid were collected 1 week prior to and 1 week after antigen challenge, and functional activity was determined by HAI assay. Data expressed are the titers of samples that inhibited influenza virus-mediated agglutination of red blood cells. *, significantly greater titer than that for samples from unvaccinated sheep at the same time point (P < 0.05; ANOVA); #, serum samples collected post-antigen challenge had a significantly greater HAI titer than samples collected from the same sheep pre-antigen challenge (P < 0.05; ANOVA).

The background levels of HAI activity in the BAL fluid of control animals were most likely due to the presence of nonspecific inhibitors, such as surfactants, that are present in the lung.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, a number of studies have explored the potential of lung vaccine delivery (9, 10, 13). The delivery of an influenza vaccine via the lungs, by exposing the recipient to the vaccine at the site of infection and thereby inducing a mucosal response, has the potential to increase the efficacy of protective immunity against this important pathogen. Using a sheep model that closely emulates human airways (12), we previously showed that pulmonary delivery of an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine leads to the induction of robust systemic and mucosal responses that are equivalent or even superior to the immune responses generated by unadjuvanted subcutaneous vaccination (15).

As a result of antigenic drift of the influenza virus, the seasonal influenza vaccine is given annually in order to ensure that the immunity generated is appropriate for the dominant circulating viral strains and persists at protective levels for the duration of the influenza season (3 to 6 months). However, in some years, there is a significant delay between vaccination and the peak of influenza virus circulation in the community, so it is also important that an influenza vaccine be able to induce an effective memory response that lasts for at least 12 months. In the current study, we evaluated the potential of a lung-delivered influenza Iscomatrix vaccine to induce long-term immunity. Circulating anti-influenza virus IgG and IgA antibodies were detectable for up to 6 months postvaccination in the sera and lungs of sheep that received 3 pulmonary immunizations with the influenza Iscomatrix vaccine, similar to the responses observed in sheep following systemic immunization with an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine (3).

In order to examine the longevity of the memory response induced by these vaccinations, animals were challenged at 6 or 12 months postvaccination, and their antibody responses were determined. A memory response to antigen exposure was detected in both serum and BAL fluid at 6 months postvaccination. Interestingly, despite the antigen challenge being delivered via the lung, a detectable memory antibody response was detected in serum but not BAL fluid at 12 months postvaccination. It should be noted that the dropoff in the IgA and IgG antibody responses was lower in the BAL fluid than in the serum. Whether the lower memory response in the lung is connected to this or indicates a mechanistic difference in the induction of systemic and mucosal memory responses to antigen challenge remains to be determined. In either case, this study demonstrates that pulmonary vaccination induces an antigen-specific memory response that endures for at least a year, resulting in a significant boost in HAI antibody titer upon antigen challenge. HAI antibody activity remains a World Health Organization accepted correlate of protection against influenza (16), although other facets of the immune response likely also play an important role in vaccine-mediated protection against influenza. For example, both serum HAI activity and nasal wash antibodies have been associated with protection induced by nasally delivered live attenuated influenza vaccines (1, 2). Importantly, our current and previous studies have shown that lung vaccination with influenza Iscomatrix vaccine induces both serum HAI activity and antigen-specific antibodies in respiratory washes (15).

The observation that antigen challenge in the lungs of vaccinated sheep can result in a clear long-term memory response in serum, but not in the lung itself, initially seems unexpected. On reflection, these responses may be logical in terms of immunobiology. The lung is obviously an essential organ which is continuously exposed to a plethora of antigens, many from pathogens. In order for the lung to remain functional, the mucosal immune system has evolved not to react to such challenges unless danger signals are received. In the case of influenza virus infection, this is believed to involve virus-mediated activation of intracellular innate immune receptors such as Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7), RIG-I, and the NLRP3 inflammasome (6). For this reason, it is logical that exposure to killed influenza virus, which will not infect host cells, induces a systemic response (in order to boost immune memory), while no local response eventuates. If the challenge had involved live virus replicating in the lung, however, which would trigger activation of intracellular innate receptors, it would be expected that the reaction in vaccinated animals would have included a rapid and robust pulmonary mucosal immune response. Since sheep cannot be infected with live influenza virus, this hypothesis cannot be tested. However, it is supported by our previous studies in which we showed that lung exposure to antigen (both influenza virus and recombinant bacterial proteins) plus immunostimulatory Iscomatrix adjuvant, which provides required danger signals, does induce a strong pulmonary antibody response shortly after vaccination (14, 15).

Finally, because bronchoscope delivery is clearly not practical for a large-scale human vaccine, alternative delivery strategies need to be developed if this technology is to be translated from animal models to humans. However, considerable work has been undertaken by biotechnology companies, with the aim to develop devices for the delivery of drugs to the lung by using aerosolized puffers (4). We envisage that the use of such a device will facilitate the large-scale delivery of influenza Iscomatrix vaccine to the deep lung of humans.

In conclusion, this study has shown that pulmonary vaccination with an influenza Iscomatrix vaccine induces an antigen-specific antibody response that is maintained at maximal levels in the BAL fluid and serum for 6 months and 3 months, respectively. This vaccine also induces a functional memory response that lasts for at least 1 year. Together, these features demonstrate the applicability of this formulation and route of delivery for use in seasonal influenza vaccinations. The use of pulmonary delivery has the potential to improve the efficacy of current influenza vaccines by inducing a strong mixed mucosal and systemic immune response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Australian Research Council Linkage Project grant LP100200728 and by CSL Limited.

We express our appreciation to Brett Walker and Darren Schooling of CSL Limited for their invaluable assistance with sheep husbandry and experimentation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Belshe RB, et al. 2000. Correlates of immune protection induced by live, attenuated, cold-adapted, trivalent, intranasal influenza virus vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 181: 1133–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clements ML, Betts RF, Tierney EL, Murphy BR. 1986. Serum and nasal wash antibodies associated with resistance to experimental challenge with influenza A wild-type virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 24: 157–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cox J, et al. 1997. Development of an influenza-IscomTM vaccine, p 33–49 In Gregoriadis G. Vaccine design: the role of cytokine networks. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dolovich MB, Dhand R. 2011. Aerosol drug delivery: developments in device design and clinical use. Lancet 377: 1032–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drane D, Gittleson C, Boyle J, Maraskovsky E. 2007. ISCOMATRIX adjuvant for prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6: 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ichinohe T. 2010. Respective roles of TLR, RIG-I and NLRP3 in influenza virus infection and immunity: impact on vaccine design. Expert Rev. Vaccines 9: 1315–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kendal AP, Pereira MS, Skehel JJ. 1982. Concepts and procedures for laboratory-based influenza surveillance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maraskovsky E, et al. 2009. Development of prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines using the ISCOMATRIX adjuvant. Immunol. Cell Biol. 87: 371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menzel M, Muellinger B, Weber N, Haeussinger K, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. 2005. Inhalative vaccination with pneumococcal polysaccharide in healthy volunteers. Vaccine 23: 5113–5119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nardelli-Haefliger D, et al. 2005. Immune responses induced by lower airway mucosal immunisation with a human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particle vaccine. Vaccine 23: 3634–3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rothberg MB, Haessler SD. 2010. Complications of seasonal and pandemic influenza. Crit. Care Med. 38: e91–e97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scheerlinck JP, Snibson KJ, Bowles VM, Sutton P. 2008. Biomedical applications of sheep models: from asthma to vaccines. Trends Biotechnol. 26: 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Song K, et al. 2010. Genetic immunization in the lung induces potent local and systemic immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107: 22213–22218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vujanic A, et al. 2010. Combined mucosal and systemic immunity following pulmonary delivery of ISCOMATRIX adjuvanted recombinant antigens. Vaccine 28: 2593–2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wee JL, et al. 2008. Pulmonary delivery of ISCOMATRIX influenza vaccine induces both systemic and mucosal immunity with antigen dose sparing. Mucosal Immunol. 1: 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO 2002. Influenza vaccines. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 77: 230–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]